Sam Harris's Blog, page 20

June 6, 2014

Clarifying the Moral Landscape

(Photo via M.Richi)

I’d like to begin, once again, by congratulating Ryan Born for winning our essay contest. The points he raised certainly merit a response. Also, I should alert readers to a change in the expected format of this debate: Originally, I had planned to have an extended conversation with the winning author, with Russell Blackford serving as both moderator and commentator. In the end, this design proved unworkable—and it was not for want of trying on our parts. I know I speak for both Ryan and Russell when I say that our failure to produce an acceptable text was frustrating. However, rather than risk boring and confusing readers with our hairsplitting and backtracking, we’ve elected to simply publish Russell’s “Judge’s Report” and Ryan’s essay, followed by my response, given here.—SH

* * *The meaning of “science”

Most criticisms of The Moral Landscape seem to stumble over its subtitle, “How Science Can Determine Human Values,” and I admit that this wording has become an albatross. To my surprise, many people think about science primarily in terms of academic titles, budgets, and architecture, and not in terms of the logical and empirical intuitions that allow us to form justified beliefs about the world. The point of my book was not to argue that “science” bureaucratically construed can subsume all talk about morality. My purpose was to show that moral truths exist and that they must fall (in principle, if not in practice) within some (perhaps never to be complete) understanding of the way conscious minds arise in this universe. For practical reasons, it is often necessary to draw boundaries between academic disciplines, but physicists, chemists, biologists, and psychologists rely on the same processes of thought and observation that govern all our efforts to stay in touch with reality. This larger domain of justified truth-claims is “science” in my sense.

For instance, what was the source of the Black Death that killed nearly half the population of Europe in the 14th century? It appears to have been Yersinia pestis, a bacterium that was delivered to unsuspecting people by fleabite. The fleas were transported to the Continent by rats, which were themselves carried by merchant ships. What kind of facts are these? Are they facts of nautical history, zoology, epidemiology, or medicine? Strange question. They belong to all these disciplines—and perhaps to several not yet invented. The only thing that matters is that this account of the Black Death appears to be true. (Note 6/9/14: Or perhaps it isn’t true.)

Another example, in case the point still isn’t clear:

You awaken to find water pouring through the ceiling of your bedroom. Imagining that you have a gaping hole in your roof, you immediately call the man who installed it. The roofer asks, “Is it raining where you live?” Good question. In fact, it hasn’t rained for months. Is this roofer a scientist? Not technically, but he was thinking just like one. Empiricism and logic reveal that your roof is not the problem.

So you call a plumber. Is a plumber a scientist? No more than a roofer is, but any competent plumber will generate hypotheses and test them—and his thinking will conform to the same principles of reasoning that every scientist uses. When he pressure tests a section of pipe, he is running an experiment. Would this experiment be more “scientific” if it were funded by the National Science Foundation? No. By contrast, when a world-famous geneticist like Francis Collins declares that the biblical God installed immortal souls, free will, and morality in one species of primate, he is repudiating the core values of science with every word. Drawing the line between science and non-science by reference to a person’s occupation is just too crude to be useful—but it is what many of my critics seem to do.

I am, in essence, defending the unity of knowledge—the idea that the boundaries between disciplines are mere conventions and that we inhabit a single epistemic sphere in which to form true beliefs about the world. This remains a controversial thesis, and it is generally met with charges of “scientism.” Sometimes, the unity of knowledge is very easy to see: Is there really a boundary between the truths of physics and those of biology? No. And yet it is practical, even necessary, to treat these disciplines separately most of the time. In this sense, the boundaries between disciplines are analogous to political borders drawn on maps. Is there really a difference between California and Arizona at their shared border? No, but we divide this stretch of desert as a matter of convention. However, once we begin talking about non-contiguous disciplines—physics and sociology, say—people worry that a single, consilient idea of truth can’t span the distance. Suddenly, the different colors on the map look hugely significant. But I’m convinced that this is an illusion.

My interest is in the nature of reality—what is actual and possible—not in how we organize our talk about it in our universities. There is nothing wrong with a mathematician’s opening a door in physics, a physicist’s making a breakthrough in neuroscience, a neuroscientist’s settling a debate in the philosophy of mind, a philosopher’s overturning our understanding of history, a historian’s transforming the field of anthropology, an anthropologist’s revolutionizing linguistics, or a linguist’s discovering something foundational about our mathematical intuitions. The circle is complete, and it simply does not matter where these people keep their offices or which journals they publish in.

Ryan wrote that my “proposed science of morality cannot offer scientific answers to questions of morality and value, because it cannot derive moral judgments solely from scientific descriptions of the world.” But no branch of science can derive its judgments solely from scientific descriptions of the world. We have intuitions of truth and falsity, logical consistency, and causality that are foundational to our thinking about anything. Certain of these intuitions can be used to trump others: We may think, for instance, that our expectations of cause and effect could be routinely violated by reality at large, and that apes like ourselves may simply be unequipped to understand what is really going on in the universe. That is a perfectly cogent idea, even though it seems to make a mockery of most of our other ideas. But the fact is that all forms of scientific inquiry pull themselves up by some intuitive bootstraps. Gödel proved this for arithmetic, and it seems intuitively obvious for other forms of reasoning as well. I invite you to define the concept of “causality” in noncircular terms if you would test this claim. Some intuitions are truly basic to our thinking. I claim that the conviction that the worst possible misery for everyone is bad and should be avoided is among them.

Contrary to what Ryan suggests, I don’t believe that the epistemic values of science are “self-justifying”—we just can’t get completely free of them. We can bracket certain of them in local cases, as we do in quantum mechanics, but these are instances in which we are then forced to admit that we don’t (yet) understand what is going on. Our knowledge of the world seems to require that it behave in certain ways (e.g. if A is bigger than B, and B is bigger than C, then A will be bigger than C). When these principles are violated, we are invariably confused.

So I think the distinction that Ryan draws between science in general and the science of medicine is unwarranted. He says, “Science cannot show empirically that health is good. But nor, I would add, can science appeal to health to defend health’s value, as it would appeal to logic to defend logic’s value.” But science can’t use logic to validate logic. It presupposes the value of logic from the start. Consequently, Ryan seems to be holding my claims about moral truth to a standard of self-justification that no branch of science can meet. Physics can’t justify the intellectual tools one needs to do physics. Does that make it unscientific?

He writes:

First, your analogy between epistemic axioms and moral axioms fails. The former merely motivate scientific inquiry and frame its development, whereas the latter predetermine your science of morality’s most basic findings. Epistemic axioms direct science to favor theories that are logically consistent, empirically supported, and so on, but they do not dictate which theories those will be.

I disagree. Epistemic axioms do more than motivate scientific inquiry. They determine what we find reasonable—or even intelligible—at every stage of that inquiry. And my notion of well-being wouldn’t “predetermine [the] science of morality’s most basic findings” because it allows for an uncountable number of peaks on the moral landscape. I trust that many of these peaks are not only stranger than I imagine but stranger than I can imagine. I am simply saying that certain of these conscious states will be better than others (by the only conception of “better” that makes any sense) and that the paths leading to them must arise out of the laws of nature. Ethics, in my view, is a navigation problem.

Again, I admit that there may be something confusing about my use of the term “science”: I want it to mean, in its broadest sense, our best effort to understand reality at every level, but I also acknowledge that it is a specialized form of any such effort. The problem, however, is that there is no telling where and how the pursuits of journalists, historians, and plumbers will become entangled with the work of official “scientists.” To cite an example I’ve used elsewhere: Was the Shroud of Turin a medieval forgery? For centuries, this was a question for historians to answer—until we developed the technique of radiocarbon dating. Now it is a question of chemistry.

I’m concerned with truth-claims generally, and with conceptually and empirically valid ways of making them. The whole point of The Moral Landscape was to argue for the existence of moral truths—and to insist that they are every bit as real as the truths of physics. If readers want to concede that point without calling the acquisition of such truths a “science,” that’s a semantic choice that has no bearing on my argument.

What we talk about when we talk about “ethics”

Ryan also seems to take for granted that the traditional categories of consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics are conceptually valid and worth maintaining. However, I believe that partitioning moral philosophy in this way begs the very question at issue—and this is one reason I tend not to identify myself as a “consequentialist.” Everyone knows—or thinks he knows—that consequentialism fails to capture much of what we value. This is true almost by definition, because, as Ryan observes, “serious competing theories of value and morality exist.”

But if the categorical imperative (one of Kant’s foundational contributions to deontology, or rule-based ethics) reliably made everyone miserable, no one would defend it as an ethical principle. Similarly, if virtues such as generosity, wisdom, and honesty caused nothing but pain and chaos, no sane person could consider them good. In my view, deontologists and virtue ethicists smuggle the good consequences of their ethics into the conversation from the start.

It seems clear that a complete scientific understanding of mind would yield a complete understanding of all the ways in which conscious beings can thrive or suffer in this universe. What would such an account leave out that we (or any other conscious being) could conceivably care about? Gender equality? Respect for authority? Courage? Intellectual honesty? Either these have consequences for the minds involved, or they have no consequences. Ryan seems to believe that a person can coherently value something for reasons that have nothing to do with its actual or potential consequences. It is true that certain philosophers have claimed this. For instance, John Rawls said that he cared about fairness and justice independent of their effects on human life. But I don’t find this claim psychologically credible or conceptually coherent. After all, these concerns predate our humanity. Do you think that capuchin monkeys are worried about fairness as an abstract principle, or do you think they just don’t like the way it feels to be treated unfairly?

Traditional moral philosophy also tends to set arbitrary limits on what counts as a consequence. Imagine, for instance, that a reckless driver is about to run over a puppy, and I, at great risk to myself, kick the puppy out of the car’s path, thereby saving its life. The consequences of my actions seem unambiguously good, and I will be a hero to animal lovers everywhere. However, let’s say that I didn’t actually see the car approaching and simply kicked the puppy because I wanted to cause it pain. Are my actions still good? Students of philosophy have been led to imagine that scenarios of this kind pose serious challenges to consequentialism.

But why should we ignore the consequences of a person’s mental states? If I am the kind of man who prefers kicking puppies to petting them, I have a mind that will reliably produce negative experiences—for both myself and others. Whatever is bad about being an abuser of puppies can be explained in terms of the consequences of living as such a person in the world. Yes, being deranged, I might get a momentary thrill from being cruel to a defenseless animal, but at what price? Do my kids love me? Am I even capable of loving them? What rewarding experiences in life am I missing? Intentions matter because they color our minds in every moment. They also determine much of our behavior, and thereby affect the lives of other people. As our minds are, so our lives (largely) become.

Of course, intentions aren’t the only things that matter, as we can readily see in this case. It is quite possible for a bad person to inadvertently do some good in the world. But the inner and outer consequences of our thoughts and actions seem to account for everything of value here. If you disagree, the burden is on you to come up with an action that is obviously right or wrong for reasons that are not fully accounted for by its (actual or potential) consequences.

The spuriousness of our traditional categories in moral philosophy can be seen in how we teach our children to be good. Why do we want them to be good in the first place? Well, at a minimum, we’d rather they not wind up bludgeoned in a ditch. More generally, we want them to flourish—to live happy, creative, meaningful lives—and to help make the world a better place. All this entails talking about rules and heuristics (deontology), a person’s character (virtue ethics), and the good and bad consequences of certain actions (consequentialism). But it all reduces to a concern for the well-being of our children and (generally to a lesser extent) of the people with whom they will interact. I don’t believe that any sane person is concerned with abstract principles and virtues—such as justice and loyalty—independent of the ways they affect our lives.

What do we mean by “should” and “ought”?

I also disagree with the distinction Ryan draws between “descriptive” and “prescriptive” enterprises. Ethics is prescriptive only because we tend to talk about it that way—and I believe this emphasis comes, in large part, from the stultifying influence of Abrahamic religion. We could just as well think about ethics descriptively. Certain experiences, relationships, social institutions, and technological developments are possible—and there are more or less direct ways to arrive at them. Again, we have a navigation problem. To say we “should” follow some of these paths and avoid others is just a way of saying that some lead to happiness and others to misery. “You shouldn’t lie” (prescriptive) is synonymous with “Lying needlessly complicates people’s lives, destroys reputations, and undermines trust” (descriptive). “We should defend democracy from totalitarianism” (prescriptive) is another way of saying “Democracy is far more conducive to human flourishing than the alternatives are” (descriptive). In my view, moralizing notions like “should” and “ought” are just ways of indicating that certain experiences and states of being are better than others.

Many readers seem confused by the fact that my account of ethics isn’t overtly prescriptive. Russell raises this point in his Judge’s Report when he writes:

This argument relies on a claim that we must all accept that a situation of universal, unremitting, and extreme agony is bad. But if we do so, does that mean we’re committed to maximizing the aggregate (or perhaps average) well-being of all conscious creatures? What if that conflicts with other values that some of us hold dear?

There need be no imperative to be good—just as there’s no imperative to be smart or even sane. A person may be wrong about what’s good for him (and for everyone else), but he’s under no obligation to correct his error—any more than he is required to understand that π is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. A person may be mistaken about how to get what he wants out of life, and he may want the wrong things (i.e., things that will reliably make him miserable), just as he may fail to form true/useful beliefs in any other area. I am simply arguing that we live in a universe in which certain conscious states are possible, some better than others, and that movement in this space will depend on the laws of nature. Ryan, Russell, and many of my other critics think that I must add an extra term of obligation—a person should be committed to maximizing the well-being of all conscious creatures. But I see no need for this.

Imagine that you could push a button that would make every person on earth a little more creative, compassionate, intelligent, and fulfilled—in such a way as to produce no negative effects, now or in the future. This would be “good” in the only moral sense of the word that I understand. However, to make this claim, one needs to posit a larger space of possible experiences (e.g. a moral landscape). What does it mean to say that a person should push this button? It means that making this choice would do a lot of good in the world without doing any harm. And a disposition to not push the button would say something very unflattering about him. After all, what possible motive could a person have for declining to increase everyone’s well-being (including his own) at no cost? I think our notions of “should” and “ought” can be derived from these facts and others like them. Pushing the button is better for everyone involved. What more do we need to motivate prescriptive judgments like “should” and “ought”?

Following Hume, many philosophers think that “should” and “ought” can only be derived from our existing desires and goals—otherwise, there simply isn’t any moral sense to be made of what “is.” But this skirts the essential point: Some people don’t know what they’re missing. Thus, their existing desires and goals are not necessarily a guide to the moral landscape. In fact, it is perfectly coherent to say that all of us live, to one or another degree, in ignorance of our deepest possible interests. I am sure that there are experiences and modes of living available to me that I really would value over all others if I were only wise enough to value them. It is only by reference to this larger space of possible experiences that my current priorities can be right or wrong. And unless one were to posit, against all evidence, that every person’s peak on this landscape is idiosyncratic and zero-sum (i.e., my greatest happiness will be unique to me and will come at the expense of everyone else’s), the best possible world for me seems very likely to be (nearly) the best possible world for everyone else. After all, do you think I’d be better off in a world filled with happy, peaceful, creative people, or one in which I drank the tears of the damned?

Part of the resistance I’ve encountered to the views presented in The Moral Landscape comes from readers who appear to want an ethical standard that gives clear guidance in every situation and doesn’t require too much of them. People want it to be easy to be good—and they don’t want to think that they are not living as good a life as they could be. This is especially true when balancing one’s personal well-being vs. the well-being of society. Most of us are profoundly selfish, and we don’t want to be told that being selfish is wrong. As I tried to make clear in the book, I don’t think it is wrong, up to a point. I suspect that an exclusive focus on the welfare of the group is not the best way to build a civilization that could secure it. Some form of enlightened selfishness seems the most reasonable approach—in which we are more concerned about ourselves and our children than about other people and their children, but not callously so. However, the well-being of the whole group is the only global standard by which we can judge specific outcomes to be good.

The question of how to think about collective well-being is a difficult one, and Russell raises this concern in his Judge’s Report. However, I think the paradoxes that Derek Parfit famously constructed here (e.g. “The Repugnant Conclusion”) are similar to Zeno’s paradoxes of motion. How do any of us get to the coffeepot in the morning if we must first travel half the distance to it, and then half again, ad infinitum? Apparently, this geometrical party trick enthralled philosophers for centuries—but I suspect that no one took Zeno so seriously as to doubt that motion was possible. Once mathematicians showed us how to sum an infinite series, the problem vanished. Whether or not we ever shake off Parfit’s paradoxes, there is no question that the limit cases exist: The worst possible misery for everyone really is worse than the greatest possible happiness. Between these two poles, it seems to me, we can talk about moral truth without hedging. We are still faced with a very real and all-too-consequential navigation problem. Where to go from here? Some experiences are sublime, and some are truly terrible—and all await discovery by the requisite minds. Certain states of pointless misery are possible—how can we avoid them? As far as I can see, saying that we “should” avoid them adds nothing to the import of the phrase “pointless misery.” Is pointless misery a bad thing? Well if it isn’t bad, what is? Even if you want to dispense with words like “bad” and “good” and remain entirely nonjudgmental, countless states of suffering and well-being are there to be realized—and we are moving toward some and away from others.

And if we are going to worry about how our provincial human purposes frame our thinking about reality, let’s worry about this consistently. Ryan writes that “Science cannot show empirically that health is good,” but he admits that, without this assumption, “the science of medicine would seem to defy conception.” I believe morality is also inconceivable without a concern for well-being and that wherever people talk about “good” and “evil” in ways that clearly have nothing to do with well-being they are misusing these terms. In fact, people have been confused about medicine, nutrition, exercise, and related topics for millennia. Even now, many of us harbor beliefs about human health that have nothing to do with biological reality. In Africa, for instance, they can’t seem to divorce their understanding of medicine from a belief in the power of sympathetic magic. Are these signs that health falls outside the purview of science?

And if we are going to balk at axiomatically valuing health or well-being, why accept any values at all in our epistemology? For instance, how is a desire to understand the world any more refined? I would argue that satisfying our curiosity is a component of our well-being, and when it isn’t—for instance, when certain forms of knowledge seem guaranteed to cause great harm—it is perfectly rational for us to decline to seek such knowledge. It seems strange for me to end on so pragmatic a note (because, as a student of Richard Rorty’s, I drove the man crazy with my realism), but we engage with reality in many modes, and curiosity is just one of them. I’m not even sure that curiosity grounds most of our empirical truth-claims. Is my knowledge that fire is hot borne of curiosity, or of my memory of having once been burned and my inclination to avoid pain and injury in the future?

We have certain logical and moral intuitions that we cannot help but rely upon to understand and judge the desirability of various states of the world. The limitations of some of these intuitions can be transcended by recourse to others that seem more fundamental. In the end, however, we must work with intuitions that strike us as non-negotiable. To ask whether the moral landscape captures our sense of moral imperative is like asking whether the physical universe is logical. The universe is whatever it is. To ask whether it is logical is simply to wonder whether we can understand it. Perhaps knowing all the laws of physics would leave us feeling that certain laws are contradictory. This wouldn’t be a problem with the universe; it would be a problem with human reasoning. Are there peaks of well-being that might strike us as morally objectionable? This wouldn’t be a problem with the universe; it would be a problem with our moral cognition.

As I argue in my book, we may think merely about what is—specifically about the possibilities of experience in this universe—and realize that this set of facts captures all that can be valued, along with every form of consciousness that could possibly value it. Either a change in the universe can affect the experience of someone, somewhere, or it can’t. I claim that only those changes that can have such effects can be coherently cared about. And if there is a credible exception to this claim, I have yet to encounter it. There is only what IS (which includes all that is possible). If you can’t find your oughts here, I can’t see any other place to look for them.

* * *

Once again, I’d like to thank Ryan and Russell for their hard work. I appreciated the chance to clarify my views, and I hope readers have found this exchange useful.

June 4, 2014

Drugs and the Meaning of Life

(Note 6/4/2014: I have made several changes to this 2011 essay and added an audio version.—SH)

Everything we do is for the purpose of altering consciousness. We form friendships so that we can feel certain emotions, like love, and avoid others, like loneliness. We eat specific foods to enjoy their fleeting presence on our tongues. We read for the pleasure of thinking another person’s thoughts. Every waking moment—and even in our dreams—we struggle to direct the flow of sensation, emotion, and cognition toward states of consciousness that we value.

Drugs are another means toward this end. Some are illegal; some are stigmatized; some are dangerous—though, perversely, these sets only partially intersect. Some drugs of extraordinary power and utility, such as psilocybin (the active compound in “magic mushrooms”) and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), pose no apparent risk of addiction and are physically well-tolerated, and yet one can still be sent to prison for their use—whereas drugs such as tobacco and alcohol, which have ruined countless lives, are enjoyed ad libitum in almost every society on earth. There are other points on this continuum: MDMA, or Ecstasy, has remarkable therapeutic potential, but it is also susceptible to abuse, and some evidence suggests that it can be neurotoxic.[]

One of the great responsibilities we have as a society is to educate ourselves, along with the next generation, about which substances are worth ingesting and for what purpose and which are not. The problem, however, is that we refer to all biologically active compounds by a single term, drugs, making it nearly impossible to have an intelligent discussion about the psychological, medical, ethical, and legal issues surrounding their use. The poverty of our language has been only slightly eased by the introduction of the term psychedelics to differentiate certain visionary compounds, which can produce extraordinary insights, from narcotics and other classic agents of stupefaction and abuse.

However, we should not be too quick to feel nostalgia for the counterculture of the 1960s. Yes, crucial breakthroughs were made, socially and psychologically, and drugs were central to the process, but one need only read accounts of the time, such as Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, to see the problem with a society bent upon rapture at any cost. For every insight of lasting value produced by drugs, there was an army of zombies with flowers in their hair shuffling toward failure and regret. Turning on, tuning in, and dropping out is wise, or even benign, only if you can then drop into a mode of life that makes ethical and material sense and doesn’t leave your children wandering in traffic.

Drug abuse and addiction are real problems, of course, the remedy for which is education and medical treatment, not incarceration. In fact, the most abused drugs in the United States now appear to be oxycodone and other prescription painkillers. Should these medicines be made illegal? Of course not. But people need to be informed about their hazards, and addicts need treatment. And all drugs—including alcohol, cigarettes, and aspirin—must be kept out of the hands of children.

I discuss issues of drug policy in some detail in my first book, The End of Faith, and my thinking on the subject has not changed. The “war on drugs” has been lost and should never have been waged. I can think of no right more fundamental than the right to peacefully steward the contents of one’s own consciousness. The fact that we pointlessly ruin the lives of nonviolent drug users by incarcerating them, at enormous expense, constitutes one of the great moral failures of our time. (And the fact that we make room for them in our prisons by paroling murderers, rapists, and child molesters makes one wonder whether civilization isn’t simply doomed.)

I have two daughters who will one day take drugs. Of course, I will do everything in my power to see that they choose their drugs wisely, but a life lived entirely without drugs is neither foreseeable nor, I think, desirable. I hope they someday enjoy a morning cup of tea or coffee as much as I do. If they drink alcohol as adults, as they probably will, I will encourage them to do it safely. If they choose to smoke marijuana, I will urge moderation.[] Tobacco should be shunned, and I will do everything within the bounds of decent parenting to steer them away from it. Needless to say, if I knew that either of my daughters would eventually develop a fondness for methamphetamine or crack cocaine, I might never sleep again. But if they don’t try a psychedelic like psilocybin or LSD at least once in their adult lives, I will wonder whether they had missed one of the most important rites of passage a human being can experience.

This is not to say that everyone should take psychedelics. As I will make clear below, these drugs pose certain dangers. Undoubtedly, some people cannot afford to give the anchor of sanity even the slightest tug. It has been many years since I took psychedelics myself, and my abstinence is born of a healthy respect for the risks involved. However, there was a period in my early twenties when I found psilocybin and LSD to be indispensable tools, and some of the most important hours of my life were spent under their influence. Without them, I might never have discovered that there was an inner landscape of mind worth exploring.

There is no getting around the role of luck here. If you are lucky, and you take the right drug, you will know what it is to be enlightened (or to be close enough to persuade you that enlightenment is possible). If you are unlucky, you will know what it is to be clinically insane. While I do not recommend the latter experience, it does increase one’s respect for the tenuous condition of sanity, as well as one’s compassion for people who suffer from mental illness.

Human beings have ingested plant-based psychedelics for millennia, but scientific research on these compounds did not begin until the 1950s. By 1965, a thousand studies had been published, primarily on psilocybin and LSD, many of which attested to the usefulness of psychedelics in the treatment of clinical depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol addiction, and the pain and anxiety associated with terminal cancer. Within a few years, however, this entire field of research was abolished in an effort to stem the spread of these drugs among the public. After a hiatus that lasted an entire generation, scientific research on the pharmacology and therapeutic value of psychedelics has quietly resumed.

Psychedelics such as psilocybin, LSD, DMT, and mescaline all powerfully alter cognition, perception, and mood. Most seem to exert their influence through the serotonin system in the brain, primarily by binding to 5-HT2A receptors (though several have affinity for other receptors as well), leading to increased activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Although the PFC in turn modulates subcortical dopamine production—and certain of these compounds, such as LSD, bind directly to dopamine receptors—the effect of psychedelics seems to take place largely outside dopamine pathways, which could explain why these drugs are not habit-forming.

The efficacy of psychedelics might seem to establish the material basis of mental and spiritual life beyond any doubt, for the introduction of these substances into the brain is the obvious cause of any numinous apocalypse that follows. It is possible, however, if not actually plausible, to seize this evidence from the other end and argue, as Aldous Huxley did in his classic The Doors of Perception, that the primary function of the brain may be eliminative: Its purpose may be to prevent a transpersonal dimension of mind from flooding consciousness, thereby allowing apes like ourselves to make their way in the world without being dazzled at every step by visionary phenomena that are irrelevant to their physical survival. Huxley thought of the brain as a kind of “reducing valve” for “Mind at Large.” In fact, the idea that the brain is a filter rather than the origin of mind goes back at least as far as Henri Bergson and William James. In Huxley’s view, this would explain the efficacy of psychedelics: They may simply be a material means of opening the tap.

Huxley was operating under the assumption that psychedelics decrease brain activity. Some recent data have lent support to this view; for instance, a neuroimaging study of psilocybin suggests that the drug primarily reduces activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, a region involved in a wide variety of tasks related to self-monitoring. However, other studies have found that psychedelics increase activity throughout the brain. Whatever the case, the action of these drugs does not rule out dualism, or the existence of realms of mind beyond the brain—but then, nothing does. That is one of the problems with views of this kind: They appear to be unfalsifiable.[]

We have reason to be skeptical of the brain-as-barrier thesis. If the brain were merely a filter on the mind, damaging it should increase cognition. In fact, strategically damaging the brain should be the most reliable method of spiritual practice available to anyone. In almost every case, loss of brain should yield more mind. But that is not how the mind works.

Some people try to get around this by suggesting that the brain may function more like a radio, a receiver of conscious states rather than a barrier to them. At first glance, this would appear to account for the deleterious effects of neurological injury and disease, for if one smashes a radio with a hammer, it will no longer function properly. There is a problem with this metaphor, however. Those who employ it invariably forget that we are the music, not the radio. If the brain were nothing more than a receiver of conscious states, it should be impossible to diminish a person’s experience of the cosmos by damaging her brain. She might seem unconscious from the outside—like a broken radio—but, subjectively speaking, the music would play on.

Specific reductions in brain activity might benefit people in certain ways, unmasking memories or abilities that are being actively inhibited by the regions in question. But there is no reason to think that the pervasive destruction of the central nervous system would leave the mind unaffected (much less improved). Medications that reduce anxiety generally work by increasing the effect of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, thereby diminishing neuronal activity in various parts of the brain. But the fact that dampening arousal in this way can make people feel better does not suggest that they would feel better still if they were drugged into a coma. Similarly, it would be unsurprising if psilocybin reduced brain activity in areas responsible for self-monitoring, because that might, in part, account for the experiences that are often associated with the drug. This does not give us any reason to believe that turning off the brain entirely would yield an increased awareness of spiritual realities.

However, the brain does exclude an extraordinary amount of information from consciousness. And, like many who have taken psychedelics, I can attest that these compounds throw open the gates. Positing the existence of a Mind at Large is more tempting in some states of consciousness than in others. But these drugs can also produce mental states that are best viewed as forms of psychosis. As a general matter, I believe we should be very slow to draw conclusions about the nature of the cosmos on the basis of inner experiences—no matter how profound they may seem.

One thing is certain: The mind is vaster and more fluid than our ordinary, waking consciousness suggests. And it is simply impossible to communicate the profundity (or seeming profundity) of psychedelic states to those who have never experienced them. Indeed, it is even difficult to remind oneself of the power of these states once they have passed.

Many people wonder about the difference between meditation (and other contemplative practices) and psychedelics. Are these drugs a form of cheating, or are they the only means of authentic awakening? They are neither. All psychoactive drugs modulate the existing neurochemistry of the brain—either by mimicking specific neurotransmitters or by causing the neurotransmitters themselves to be more or less active. Everything that one can experience on a drug is, at some level, an expression of the brain’s potential. Hence, whatever one has seen or felt after ingesting LSD is likely to have been seen or felt by someone, somewhere, without it.

However, it cannot be denied that psychedelics are a uniquely potent means of altering consciousness. Teach a person to meditate, pray, chant, or do yoga, and there is no guarantee that anything will happen. Depending upon his aptitude or interest, the only reward for his efforts may be boredom and a sore back. If, however, a person ingests 100 micrograms of LSD, what happens next will depend on a variety of factors, but there is no question that something will happen. And boredom is simply not in the cards. Within the hour, the significance of his existence will bear down upon him like an avalanche. As the late Terence McKenna[] never tired of pointing out, this guarantee of profound effect, for better or worse, is what separates psychedelics from every other method of spiritual inquiry.

Ingesting a powerful dose of a psychedelic drug is like strapping oneself to a rocket without a guidance system. One might wind up somewhere worth going, and, depending on the compound and one’s “set and setting,” certain trajectories are more likely than others. But however methodically one prepares for the voyage, one can still be hurled into states of mind so painful and confusing as to be indistinguishable from psychosis. Hence, the terms psychotomimetic and psychotogenic that are occasionally applied to these drugs.

I have visited both extremes on the psychedelic continuum. The positive experiences were more sublime than I could ever have imagined or than I can now faithfully recall. These chemicals disclose layers of beauty that art is powerless to capture and for which the beauty of nature itself is a mere simulacrum. It is one thing to be awestruck by the sight of a giant redwood and amazed at the details of its history and underlying biology. It is quite another to spend an apparent eternity in egoless communion with it. Positive psychedelic experiences often reveal how wondrously at ease in the universe a human being can be—and for most of us, normal waking consciousness does not offer so much as a glimmer of those deeper possibilities.

People generally come away from such experiences with a sense that conventional states of consciousness obscure and truncate sacred insights and emotions. If the patriarchs and matriarchs of the world’s religions experienced such states of mind, many of their claims about the nature of reality would make subjective sense. A beatific vision does not tell you anything about the birth of the cosmos, but it does reveal how utterly transfigured a mind can be by a full collision with the present moment.

However, as the peaks are high, the valleys are deep. My “bad trips” were, without question, the most harrowing hours I have ever endured, and they make the notion of hell—as a metaphor if not an actual destination—seem perfectly apt. If nothing else, these excruciating experiences can become a source of compassion. I think it may be impossible to imagine what it is like to suffer from mental illness without having briefly touched its shores.

At both ends of the continuum, time dilates in ways that cannot be described—apart from merely observing that these experiences can seem eternal. I have spent hours, both good and bad, in which any understanding that I had ingested a drug was lost, and all memories of my past along with it. Immersion in the present moment to this degree is synonymous with the feeling that one has always been and will always be in precisely this condition. Depending on the character of one’s experience at that point, notions of salvation or damnation may well apply. Blake’s line about beholding “eternity in an hour” neither promises nor threatens too much.

In the beginning, my experiences with psilocybin and LSD were so positive that I did not see how a bad trip could be possible. Notions of “set and setting,” admittedly vague, seemed sufficient to account for my good luck. My mental set was exactly as it needed to be—I was a spiritually serious investigator of my own mind—and my setting was generally one of either natural beauty or secure solitude.

I cannot account for why my adventures with psychedelics were uniformly pleasant until they weren’t, but once the doors to hell opened, they appeared to have been left permanently ajar. Thereafter, whether or not a trip was good in the aggregate, it generally entailed some excruciating detour on the path to sublimity. Have you ever traveled, beyond all mere metaphors, to the Mountain of Shame and stayed for a thousand years? I do not recommend it.

(Pokhara, Nepal)

On my first trip to Nepal, I took a rowboat out on Phewa Lake in Pokhara, which offers a stunning view of the Annapurna range. It was early morning, and I was alone. As the sun rose over the water, I ingested 400 micrograms of LSD. I was twenty years old and had taken the drug at least ten times previously. What could go wrong?

Everything, as it turns out. Well, not everything—I didn’t drown. I have a vague memory of drifting ashore and being surrounded by a group of Nepali soldiers. After watching me for a while, as I ogled them over the gunwale like a lunatic, they seemed on the verge of deciding what to do with me. Some polite words of Esperanto and a few mad oar strokes, and I was offshore and into oblivion. I suppose that could have ended differently.

But soon there was no lake or mountains or boat—and if I had fallen into the water, I am pretty sure there would have been no one to swim. For the next several hours my mind became a perfect instrument of self-torture. All that remained was a continuous shattering and terror for which I have no words.

An encounter like that takes something out of you. Even if LSD and similar drugs are biologically safe, they have the potential to produce extremely unpleasant and destabilizing experiences. I believe I was positively affected by my good trips, and negatively affected by the bad ones, for weeks and months.

Meditation can open the mind to a similar range of conscious states, but far less haphazardly. If LSD is like being strapped to a rocket, learning to meditate is like gently raising a sail. Yes, it is possible, even with guidance, to wind up someplace terrifying, and some people probably shouldn’t spend long periods in intensive practice. But the general effect of meditation training is of settling ever more fully into one’s own skin and suffering less there.

As I discussed in The End of Faith, I view most psychedelic experiences as potentially misleading. Psychedelics do not guarantee wisdom or a clear recognition of the selfless nature of consciousness. They merely guarantee that the contents of consciousness will change. Such visionary experiences, considered in their totality, appear to me to be ethically neutral. Therefore, it seems that psychedelic ecstasies must be steered toward our personal and collective well-being by some other principle. As Daniel Pinchbeck pointed out in his highly entertaining book Breaking Open the Head, the fact that both the Mayans and the Aztecs used psychedelics, while being enthusiastic practitioners of human sacrifice, makes any idealistic connection between plant-based shamanism and an enlightened society seem terribly naïve.

As I discuss elsewhere in my work, the form of transcendence that appears to link directly to ethical behavior and human well-being is that which occurs in the midst of ordinary waking life. It is by ceasing to cling to the contents of consciousness—to our thoughts, moods, and desires— that we make progress. This project does not in principle require that we experience more content.[] The freedom from self that is both the goal and foundation of “spiritual” life is coincident with normal perception and cognition—though, admittedly, this can be difficult to realize.

The power of psychedelics, however, is that they often reveal, in the span of a few hours, depths of awe and understanding that can otherwise elude us for a lifetime. William James said it about as well as anyone:[]

One conclusion was forced upon my mind at that time, and my impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded. How to regard them is the question,—for they are so discontinuous with ordinary consciousness. Yet they may determine attitudes though they cannot furnish formulas, and open a region though they fail to give a map. At any rate, they forbid a premature closing of our accounts with reality.

(The Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 388)

I believe that psychedelics may be indispensable for some people—especially those who, like me, initially need convincing that profound changes in consciousness are possible. After that, it seems wise to find ways of practicing that do not present the same risks. Happily, such methods are widely available.

NOTES:

What is moderation? Let’s just say that I’ve never met a person who smokes marijuana every day who I thought wouldn’t benefit from smoking less (and I’ve never met someone who has never tried it who I thought wouldn’t benefit from smoking more).↩

Physicalism, by contrast, could be easily falsified. If science ever established the existence of ghosts, or reincarnation, or any other phenomenon which would place the human mind (in whole or in part) outside the brain, physicalism would be dead. The fact that dualists can never say what would count as evidence against their views makes this ancient philosophical position very difficult to distinguish from religious faith.↩

Terence McKenna is one person I regret not getting to know. Unfortunately, he died from brain cancer in 2000, at the age of 53. His books are well worth reading, and I have recommended several below, but he was, above all, an amazing speaker. It is true that his eloquence often led him to adopt positions which can only be described (charitably) as “wacky,” but the man was undeniably brilliant and always worth listening to. ↩

I should say, however, that there are psychedelic experiences that I have not had, which appear to deliver a different message. Rather than being states in which the boundaries of the self are dissolved, some people have experiences in which the self (in some form) appears to be transported elsewhere. This phenomenon is very common with the drug DMT, and it can lead its initiates to some very startling conclusions about the nature of reality. More than anyone else, Terence McKenna was influential in bringing the phenomenology of DMT into prominence.

DMT is unique among psychedelics for a several reasons. Everyone who has tried it seems to agree that it is the most potent hallucinogen available (not in terms of the quantity needed for an effective dose, but in terms of its effects). It is also, paradoxically, the shortest acting. While the effects of LSD can last ten hours, the DMT trance dawns in less than a minute and subsides in ten. One reason for such steep pharmacokinetics seems to be that this compound already exists inside the human brain, and it is readily metabolized by monoaminoxidase. DMT is in the same chemical class as psilocybin and the neurotransmitter serotonin (but, in addition to having an affinity for 5-HT2A receptors, it has been shown to bind to the sigma-1 receptor and modulate Na+ channels). Its function in the human body remains mysterious. Among the many mysteries and insults presented by DMT, it offers a final mockery of our drug laws: Not only have we criminalized naturally occurring substances, like cannabis; we have criminalized one of our own neurotransmitters.

Many users of DMT report being thrust under its influence into an adjacent reality where they are met by alien beings who appear intent upon sharing information and demonstrating the use of inscrutable technologies. The convergence of hundreds of such reports, many from first-time users of the drug who have not been told what to expect, is certainly interesting. It is also worth noting these accounts are almost entirely free of religious imagery. One appears far more likely to meet extraterrestrials or elves on DMT than traditional saints or angels. As I have not tried DMT, and have not had an experience of the sort that its users describe, I don’t know what to make of any of this. ↩

Of course, James was reporting his experiences with nitrous oxide, which is an anesthetic. Other anesthetics, like ketamine hydrochloride and phencyclidine hydrochloride (PCP), have similar effects on mood and cognition at low doses. However, there are many differences between these drugs and classic psychedelics—one being that high doses of the latter do not lead to general anesthesia. ↩

Recommended Reading:

Huxley, A. The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell .

.

McKenna, T. True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author’s Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil’s Paradise .

.

Pinchbeck, D. Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journey into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism .

.

Stevens, J. Storming Heaven: LSD and the American Dream .

.

Ratsch, C. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications .

.

Ott, J. Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, Their Plant Sources and History .

.

Strassman, R. DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor’s Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences .

.

Related article: What’s the Point of Transcendence?

May 31, 2014

The Moral Landscape Challenge

(Photo via Steven Kersting)

Last August, I issued the following challenge:

It has been nearly three years since The Moral Landscape was first published in English, and in that time it has been attacked by readers and nonreaders alike. Many seem to have judged from the resulting cacophony that the book’s central thesis was easily refuted. However, I have yet to encounter a substantial criticism that I feel was not adequately answered in the book itself (and in subsequent talks).

So I would like to issue a public challenge. Anyone who believes that my case for a scientific understanding of morality is mistaken is invited to prove it in under 1,000 words. (You must address the central argument of the book—not peripheral issues.) The best response will be published on this website, and its author will receive $2,000. If any essay actually persuades me, however, its author will receive $20,000, and I will publicly recant my view.

Several hundred of you entered this contest—which was an extremely gratifying turnout. The philosopher Russell Blackford judged the essays and picked a winner. Here begins my exchange with its author, Ryan Born.—SH

* * *

Russell Blackford is a conjoint lecturer in the School of Humanities and Social Science at the University of Newcastle, Australia. He is a philosopher, a literary critic, and a commentator on a range of topics including legal and political philosophy, philosophy of religion, meta-ethics, and philosophical bioethics. His works include Freedom of Religion and the Secular State, 50 Great Myths About Atheism (co-authored with Udo Schuklenk), and Humanity Enhanced: Genetic Choice and the Challenge for Liberal Democracies. Dr. Blackford is the editor in chief of The Journal of Evolution and Technology.

Ryan Born holds a BA in cognitive science from the University of Georgia and an MA in philosophy from Georgia State University. He blogs at Pointofcontroversy.com.

* * *

Judge’s report

The Moral Landscape Challenge attracted well over 400 essays, and the standard was high. Almost all entries were thoughtful; almost none took an abusive tone; and many were sophisticated and impressive. A notably large proportion—perhaps even the majority—found merit in the ideas advocated in The Moral Landscape while also perceiving limitations or weaknesses. Alas, there was no agreement on just what those might be!

A considerable number of the authors offered their personal thanks or good wishes to Sam Harris and his family, sometimes commenting about the value they’d found in Sam’s writings over the past decade, even if they perceived problems with certain of The Moral Landscape’s central claims and arguments. In all, much goodwill was shown, which helped make the contest far more enjoyable to judge than it might have been. My thanks to the many entrants who took part in such a pleasing spirit.

We could have only one winner. All the same, there’s much worth discussing in the 400-plus other entries, so I encourage the authors to present their ideas in whatever forums are available to them. In many cases, this will mean publication on personal blogs; I should note that some entries have already been published online. The issues raised by The Moral Landscape and the Moral Landscape Challenge are of great interest and importance, and I hope the debate continues. If that is one outcome of the competition, it will have achieved something worthwhile. Which prompts me to add my own thanks to Sam, both for conducting such a productive competition in the first place and for inviting me to judge it.

The criticisms put forward in the essays varied considerably, although there were some popular themes. Some entrants attacked the validity of The Moral Landscape’s central argument as Sam represented and summarized it on his website in announcing the challenge. For me, this raises an interesting question as to whether the book’s actual argument may be more complex and subtle than the website suggests. Even if the argument as presented there is invalid, that is not necessarily fatal to the book or its overall thesis.

Other essays questioned whether well-being is a concept that can be used to measure or rank moral systems, customary practices, etc., objectively. Although the authors pursued this question in a variety of ways, most did not deny that whatever might be encompassed by the concept of well-being is of some relevance when we try to evaluate or influence moral systems. They did, however, see various limits to how far we can employ the concept. Unfortunately, this brief report is not the place for me to try to settle the issues.

Others challenged the “worst possible misery for everyone” argument in Chapter 1 of The Moral Landscape. This argument relies on a claim that we must all accept that a situation of universal, unremitting, and extreme agony is bad. But if we do so, does that mean we’re committed to maximizing the aggregate (or perhaps average) well-being of all conscious creatures? What if that conflicts with other values that some of us hold dear? Even if all people who are likely to read such a book evaluated the worst possible misery for everyone as very bad indeed, could we really, even in principle, produce an objective, uncontroversial rank order of all the other possible situations that might have diverse redeeming features?

To be fair, The Moral Landscape addresses some of the problems that arise here, though of course many entrants to the competition argued that it does so inadequately. Again, complex issues surfaced in the essays, as they do in the book itself, and they will need to be explored on another occasion.

A variety of other objections were made, but one of the most common was that the moral theory developed in The Moral Landscape is not really one in which science determines human values. Rather, the primary value, that of “the well-being of conscious creatures,” is not a scientific finding. Nor is it a value that science inevitably presupposes (as it arguably must presuppose certain standards of evidence and logic). Instead, this value must come from elsewhere and can be defended only through conceptual analysis, other forms of philosophical reasoning, or appeals to our intuitions.

Such was the point pursued by the winner of the competition, Ryan Born, who presented it the most persuasively, in my view (although he had some close rivals among the other entrants). Others might have been worthy winners, but I was especially impressed by the penetration and clarity of Ryan’s essay.

Ryan is from Atlanta, where he has taught philosophy at Georgia State University. Without more fuss, I’ll let him commence what should be an interesting exchange.

—Russell Blackford, May 2014

* * *

Ryan Born: In issuing the Moral Landscape Challenge, you suggested some ways to refute your claim that questions of morality and value have scientific answers. One was to show that “other branches of science are self-justifying in a way that a science of morality could never be.” Here you seem to invite the “Value Problem” objection to your thesis, which you attempted to meet in your book’s afterword. I’ll be renewing that objection. Despite your efforts to invalidate it, the Value Problem remains a serious challenge to your thesis.

The “Value Problem” is your term for a common criticism of your proposed science of morality—namely, that it presupposes answers to fundamental questions of morality and value. You claim that what is good (the basic value question) is that which supports the well-being of conscious creatures, and that what one ought to do (the basic moral question) is maximize the well-being of conscious creatures. But science cannot empirically support either claim. Even granting that both claims are objectively true, science can do little more than fill in the descriptive empirical particulars. Such particulars may help illuminate specific moral values and principles, but only in light of the general ones you presuppose. Thus, your proposed science of morality cannot offer scientific answers to questions of morality and value, because it cannot derive moral judgments solely from scientific descriptions of the world.

You respond to the Value Problem in the following way: Every science must presuppose evaluative judgments. Science requires epistemic values—e.g., truth, logical consistency, empirical evidence. Science cannot defend these values, at least not without presupposing them in that very defense. After all, a compelling empirical case for the three values just named must show that they are truly values by using a logically consistent argument that employs empirical evidence. So when you speak of science as “self-justifying,” you appear to refer to the reflexive justification of certain epistemic values that all sciences share. But then you also note that the science of medicine requires a non-epistemic value—health. Science cannot show empirically that health is good. But nor, I would add, can science appeal to health to defend health’s value, as it would appeal to logic to defend logic’s value. Still, by definition, the science of medicine seeks to promote health (or else combat disease, which in turn promotes health). Insofar as you take the science of medicine to be “self-justifying,” you appear to hold that the very meaning of the science of medicine entails its non-epistemic evaluative foundation. From these two analogies (one to epistemic values, the other to medicine), you conclude that your proposed science of morality, in pulling itself up by the evaluative bootstraps, does no different from the science of medicine or science as a whole. In your view, to make any scientific claim, we must presuppose certain evaluative axioms.

Neither of your analogies invalidates the Value Problem. First, your analogy between epistemic axioms and moral axioms fails. The former merely motivate scientific inquiry and frame its development, whereas the latter predetermine your science of morality’s most basic findings. Epistemic axioms direct science to favor theories that are logically consistent, empirically supported, and so on, but they do not dictate which theories those will be. Meanwhile, your two moral axioms have already declared that (i) the only thing of intrinsic value is well-being, and (ii) the correct moral theory is consequentialist and, seemingly, some version of utilitarianism—rather than, say, virtue ethics, a non-consequentialist candidate for a naturalized moral framework. Further, both (i) and (ii) resist the sort of self-justification attributed above to science’s epistemic axioms; that is, neither is any more self-affirming than the value of health and the goal of promoting it. You might reply that the non-epistemic axioms of the science of medicine enjoy the sort of self-justification you have in mind for the moral (and likewise non-epistemic) axioms of your science of morality. But then your second analogy, between the science of medicine and your science of morality, fails. The former must presuppose that health is good and ought to be promoted; otherwise, the science of medicine would seem to defy conception. In contrast, a science of morality, insofar as it admits of conception, does not have to presuppose that well-being is the highest good and ought to be maximized. Serious competing theories of value and morality exist. If a science of morality elucidates moral reality, as you suggest, then presumably it must work out, not simply presuppose, the correct theory of moral reality, just as the science of physics must work out the correct theory of physical reality.

Nevertheless, you seem to believe you have worked out, scientifically, that your form of consequentialism, grounded in the supreme intrinsic value of well-being, is correct. Your defense of this moral theory is conceptual, not empirical, and requires engagement with work in moral philosophy, the intellectual home of consequentialism (in its myriad guises) and its competitors. Yet you identify science, not philosophy, as the arbiter of moral reality. In your view, no significant boundary exists between science and philosophy. In your book, you say that “science is often a matter of philosophy in practice,” subsequently reminding readers that the natural sciences were once known as natural philosophy. Bear in mind, however, the reason natural philosophy became the natural sciences: The problems it addressed became ever more empirically tractable. Indeed, some contemporary analytic philosophers hold that metaphysics will eventually yield (more or less) to the natural sciences. But even if that most rarefied of philosophical disciplines does fall to earth, metaphysics is a descriptive enterprise, just as science is conventionally taken to be. Ethics, i.e. moral philosophy, is a prescriptive enterprise, and thus will not yield so easily.

For now, I say you have not brought questions of ethics into science’s domain. No empirical inquiry into such questions can determine anything of clear moral significance without having normative conceptual answers already in place. And finding and justifying those answers requires a distinctly philosophical, not scientific, approach.

* * *

I’d like to congratulate Ryan for writing such an excellent essay and winning our contest. I would also like to thank Russell for doing the heroic work of judging the entries. I will respond in my next blog post.—SH

May 26, 2014

Adventures in the Land of Illness

(Photo via Ryan Heaney)

I can now say, at the advanced age of 47, that I no longer take my health for granted. In truth, I’ve always been a bit of a hypochondriac—but, as any hypochondriac aware of the relevant science can tell you, I am perfectly justified in this. If I wash my hands more often than your uncle with obsessive-compulsive disorder does, it’s because hand washing really is the best way to avoid most forms of contagious illness.

Until recently, my physical complaints were always minor and self-limiting, and were invariably treated as such by doctors. When I was in my twenties and thirties, having escaped childhood cancers and other serious strains of bad luck, every doctor knew that whatever seemed to be wrong with me would probably sort itself out. After I turned forty, however, I began to notice a change in attitude: Doctors suddenly took my aches and pains quite seriously. Many seemed frankly open to the possibility that I could die at any moment. Cancer, heart disease, Parkinson’s—these and other delights were now on the menu. The body is like a clock—and it is a perverse one. It is by growing less and less reliable that it signals the passage of time. What time is it now? It’s time to worry about your prostate, you poor son of a bitch…

Everyone understands that aging is a process of losing ground to the conquests of time. But apart from cosmetic changes, my first real experience of the finality of these losses came when I suddenly started experiencing tinnitus after I turned 40. I remember the moment of onset clearly: I was at the 2007 Aspen Ideas Festival and suddenly noticed a high-frequency ringing in my right ear. Seven years have passed, and the ringing hasn’t stopped. Like any other physical complaint, tinnitus can range from the scarcely consequential to the life-wrecking. I would put mine somewhere in between. I certainly mourn the loss of silence. In its place, I have an endless whistle—part cricket, part electrical interference—that makes any condition of external silence unpleasant. This sound is the first thing I notice upon waking, and it waxes and wanes throughout the day. Only significant external noise—a loud restaurant, for instance—can mask it.

On the few occasions when I’ve referred to tinnitus in my work—as an example of a private phenomenon that we can speak about objectively—I’ve heard from readers also suffering from this condition who are extremely grateful to hear it talked about in public. That is one of the reasons I have produced this essay. Many people who experience illness imagine that everyone else is blissfully getting on with life in perfect health—and this illusion compounds their suffering. So while I would generally prefer to keep my health problems private, I’ve been moved by the response I’ve gotten to my mentioning tinnitus in the past—as well as by emails I’ve received from people suffering from conditions far worse—to share my further adventures in the land of illness.

Last fall, in addition to the tinnitus, I began to experience dizziness—an undulating instability reminiscent of one’s first steps on dry land after several days at sea. When seated or standing, I often feel as if I were in a car that has suddenly accelerated or on an elevator that has just begun its descent. Combined with the tinnitus, the feeling recalls the aftermath of having been hit hard in the head. As a martial artist, I left off voluntarily acquiring brain trauma decades ago, but now my bell seems to be perpetually getting rung by an unseen opponent. In the beginning, these vestibular symptoms were accompanied by low-grade nausea. That has abated, thankfully, but my body has remained in the grip of strange new forces for more than six months. This sudden change in my health has given me great respect for how precarious the feeling of physical well-being can be.

As you might imagine, the onset of these symptoms was followed by an increasingly frantic search for a diagnosis and a rational course of treatment. Unfortunately, both have so far eluded me. Because of my tinnitus, episodic hearing loss, and other inner ear symptoms, a diagnosis of Ménière’s disease was tempting—and I lived for several months believing that I had this condition. A few minutes online can yield a bounty of terrors: Ménière’s sufferers sometimes have something called a “drop attack”—a sudden onset of vertigo so severe that it literally knocks them off their feet and keeps them down for hours. There is no acknowledged cure for this condition, and the available treatments seem both risky and ineffective. Receiving a diagnosis of Ménière’s, I was told to go on a low-sodium diet and cut out alcohol and caffeine—life changes that appeared calculated to further depress me.

If it was Ménière’s, however, mine was an atypical case—and rival diagnoses were soon forthcoming. One otologist believes I am suffering from vestibular migraines—for which he prescribed supplements and further dietary restrictions. A neurologist diagnosed me with mal de debarquement (French for “disembarkment sickness”), in which people who have traveled by boat experience a perpetual swaying once they return to land. But I hadn’t traveled by boat, or even by plane, for many months prior to the onset of my symptoms. More important, neither of these diagnoses accounts for my tinnitus. Nevertheless, my neurologist recommended that we treat my disorder empirically, and offered me a long list of anticonvulsants and antidepressants that he thought held promise. Feeling desperate, having suffered for months with no relief in sight, I picked one: Let’s give Cymbalta a try…

Being generally averse to taking medication, and knowing the power of the “nocebo” effect (the evil twin of the placebo effect), I deliberately did not look up the list of side effects for this drug. I also started at half the lowest effective dose. After a day or two, I detected a new form of unpleasantness—a slight stupor—superimposed upon my dizziness. I was also finding it difficult to urinate. On a whim, I consulted the oracle: A Google search for “Cymbalta and diff-” helpfully autocompleted to “Cymbalta and difficulty urinating.” Two minutes of reading convinced me that I was experiencing a rare and worrying side effect of the medication. I stopped taking it at once, but the urinary symptoms persisted. A trip to the urologist delivered a rival diagnosis of prostatitis. Perhaps its onset after my first dose of Cymbalta was just a coincidence. The remedy? “Eat an even more boring diet than the one you’re on for your ear.”

None of these health complaints were life-threatening, but I was beginning to feel like an invalid. And I was now visibly surrounded by the elderly and infirm. There is nothing like the waiting room of a urologist’s office to make one feel that one has grown old before one’s time—except for the waiting room of a hearing and balance specialist. Judging from the look of things, the median age in both places is about eighty. (For years, this also seemed to be the median age of my atheist fans.)

It has been interesting for me, as a proponent of science and skepticism, to experience the feelings of vulnerability and desperation that come with an illness for which science has no clear remedy or even a diagnosis. Acupuncture? Sure, let’s give that a try. Regenokine therapy? It seems to have cured Dana White, the UFC promoter, of his Ménière’s disease. Regenokine is a procedure in which a large sample of one’s own blood is spun, heated, and incubated—and a fraction thereof, thought to contain anti-inflammatory properties, is injected back into the problem area. It is, however, exclusively prescribed for orthopedic injuries. So White’s purported cure was an off-label use of a fringe treatment. It also cost $10,000.

But Regenokine might also heal my injured hip!—another geriatric complaint I had acquired courtesy of my obsession with Brazilian Jiu-jitsu. Injure your neck or your knee, and you will feel like an athlete who must simply bide his time. Injure your hip, and you will feel like someone’s shuffling grandpa. But Kobe Bryant received Regenokine for his knees with apparent success. My friend Joe Rogan had it for his back and is a believer. Six rounds of injections into my hip socket later, I’m not sure it was anything more than a scary form of acupuncture. My hip is a little better, and I’m training in BJJ again—but my recovery could well be explained by the passage of time. I am, however, rather comfortable with needles now.

As someone who will soon release a book about meditation, the illusion of the self, and the transcendence of unnecessary suffering, I feel I should offer some account of how my own mind has fared when tested in this way. I’m happy to say that it is possible to find equanimity in the midst of unpleasant experiences like these. But I am also humbled by how often I forget this.

Framing is an important variable here: If my neighbor had a machine in his backyard that emitted a high-pitched squeal identical to my tinnitus, I would never stop suing him. If his machine was also producing my dizziness, and the law offered no recourse, I might very well enforce a law of my own. However, given that my enemy is my own body, equanimity is much easier to achieve.

Of course, worrying about the future is a recipe for unhappiness. “What if this gets worse? What if I’m permanently incapacitated?” If the answer to a question cannot be known and would serve no purpose even if one could know it, there is no point in asking the question. The truth is that I don’t know how I will feel an hour from now, much less next year.

I have also noticed a propensity in myself to complain—especially to my wife—which seems profoundly unhelpful. Complaining is, nevertheless, a very seductive behavior. Why do I do it? On one level, I am just being honest: I am simply not pretending to feel better than I do. But in rejecting pretense, I am actually increasing my suffering, and worrying my wife in the process. Complaining now strikes me as a toxic form of intimacy. It is surely best to “keep calm and carry on,” as the British wartime slogan ran. Like meditation, this takes practice.

My vestibular symptoms first emerged as I was finalizing the text of Waking Up, so I do not discuss them in the book. The point of this essay is to report that the case I make in the book still stands: Meditation really works—at least at my current level of inconvenience. It is possible to accept the present moment fully, even when it isn’t the present one wants. If this offers encouragement to any of you who are dealing with similar challenges, I will be very happy.

April 12, 2014

Taming the Mind

(Photo via h.koppdelaney)

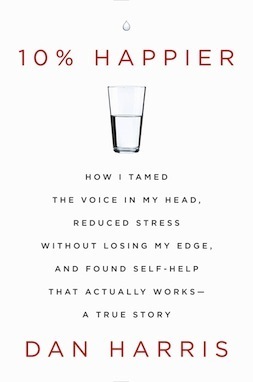

Dan Harris is a co-anchor of Nightline and the weekend edition of Good Morning America on ABC News. He has reported from all over the world, covering wars in Afghanistan, Israel/Palestine, and Iraq, and producing investigative reports in Haiti, Cambodia, and the Congo. He has also spent many years covering religion in America, despite the fact that he is agnostic.

Dan’s new book, 10 Percent Happier: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head, Reduced Stress Without Losing My Edge, and Found Self-Help That Actually Works—A True Story, hit #1 on the New York Times best-seller list.

Dan was kind enough to discuss the practice of meditation with me for this page.

* * *

Sam: One thing I love about your book—admittedly, somewhat selfishly—is that it’s exactly the book I would want people to read before Waking Up comes out in the fall. You approach the topic of meditation with serious skepticism—which, as you know, is an attitude that my readers share to an unusual degree. Perhaps you can say something about this. How did you view the practice in the beginning?