Sam Harris's Blog, page 17

February 27, 2015

The Art and Science of the Possible

Mick Ebeling is a film/television/commercial producer, philanthropist, technology trailblazer, author, entrepreneur, and public speaker. He was one of Advertising Age’s “Top 50 Most Creative People of 2014” and winner of the 2014 Muhammad Ali Humanitarian of the Year Award. Ebeling is CEO of Not Impossible Labs, an organization that develops creative solutions to real-world problems.

Ebeling’s first book is Not Impossible: The Art and Joy of Doing What Couldn’t Be Done.

* * *

Harris: Perhaps you can tell those readers who may be unfamiliar with your work what you are doing and how you came to be doing it.

Ebeling: The concept of Not Impossible began when I met an infamous LA-based graffiti artist named Tempt who was completely paralyzed with ALS. I met him at a time in my life when I felt the need to do something more in this world for others. I ended up taking a meeting with Tempt’s family, and in that meeting they shared with me that they wanted nothing more than to communicate with him again. Being a father and a brother, I connected with their struggle and decided to do everything I could to help. I enthusiastically (and prematurely, mind you) committed to finding them a solution—and thus the path of Not Impossible began.

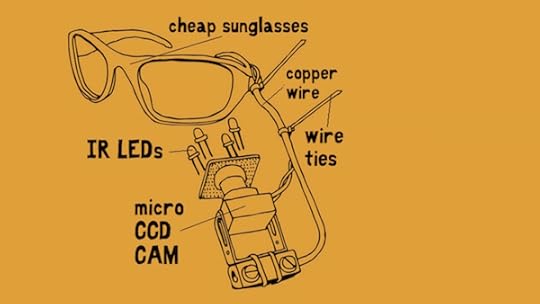

So, with a motley crew of hackers, a cheap pair of sunglasses, some copper wire, a PS3 camera that we hacked open and mounted on an LED light, and some odds and ends from Home Depot and Radio Shack, we developed a device for him called the EyeWriter. The EyeWriter used ocular recognition technology to help Tempt create art again. We then made both the code and the instructions for building an EyeWriter open source, because we wanted others to have access to this technology, and I didn’t feel that people’s socioeconomic status should govern whether or not they had the ability to communicate with their families. I found myself wanting to continue this mission of helping other people, and Not Impossible has been around ever since, hacking and creating “technology for the sake of humanity.”

Harris: Your willingness to plunge into totally unfamiliar territory is both fascinating and inspiring. Can you tell us more about what it’s been like to do this?

Ebeling: The projects we have completed certainly have been daunting, given my lack of expertise in the areas we were addressing. My background is in production—specifically in animation and design. Being surrounded daily by all these incredible machines that allow artists’ visions to go from their heads to their hands and onto the screen, I felt there had to be some way we could help Tempt create art again and just skip the hands part. The big question was not why but how we would do this. Using every resource I could think of, I brought together a group of great scientific minds to help brainstorm and create the EyeWriter. This group of guys knew how to take apart any device and put it back together in a way I never could.

What I learned from the experience of the EyeWriter is that we humans can mold technology to fulfill our needs. The famous quote “Everything that can be invented has been invented” is so very true. All the EyeWriter’s parts were pre-existing. We “invented” nothing. We merely created a new combination of that technology to fulfill our purpose. The technology is hardly transcendent. It is merely progress. The EyeWriter ended up winning all sorts of accolades, such as inclusion in Time’s Top 50 Inventions, and is now a permanent installation at MOMA in New York. From the incredible (and unplanned) success of that project, I knew that moving forward, there really was no obstacle that could prevent me from using technology to help someone.

Harris: Do you have any general insights or words of caution to share on the basis of this experience?

Ebeling: Two insights that Not Impossible has given me:

1. Technology is not just about the latest and greatest gadget. Science and technology have immense potential to help humanity when approached from the standpoint of making things highly functional and accessible (read: cheap). Through our desire to innovate, technology can become a more durable, more intelligent, and more accessible tool, especially when it is shared freely and without the governing concept of IP and ownership baked into every decision that is made.

2. The philosophy that nothing is impossible isn’t religious dogma. It does not require faith. It is 100% statistical. Every single thing that surrounds us and that is possible today was impossible before it was possible. It is incredibly narcissistic for anyone to think of his or her self as the only person who has finally reached the one single thing that is impossible, the first “impasse” that can never be solved. It might take a while—weeks, days, years—but it is inevitable that eventually ____?____ will be possible. I find that enormously motivating and comforting at the same time.

BUY THE BOOK:

February 17, 2015

The Chapel Hill Murders and ‘Militant’ Atheism

Sam Harris responds to the charge that “militant” atheism is responsible for the murder of three Muslim students in North Carolina.

Note 2/18/15: Here was Reza Aslan’s response to this podcast:

Starting to get creeped out by how obsessed Sam Harris is with me & @ggreenwald -as tho we've given him a 2nd thought http://t.co/RSbvjck96Q

— Reza Aslan (@rezaaslan) February 18, 2015

@neiltwit @ggreenwald @SamHarrisOrg oh no was I mean to your Sam? did I hurt your feelings?

— Reza Aslan (@rezaaslan) February 18, 2015

Very interesting. Aslan writes articles about me, hires people to write even longer ones (Nathan Lean is the editor-in-chief of Aslan Media), continually mentions me and distorts my views in his press appearances, and tweets about me with abandon—and he believes that I’m obsessed with him. It is safe to say that I would never mention Aslan again if he stopped spreading lies about me.—SH

February 11, 2015

Chapel Hill killings shine light on particular tensions between Islam and atheism

January 26, 2015

On Being Right about Right and Wrong

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a monthly columnist for Scientific American, the host of the Skeptics Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His latest book is The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity Toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom.

Michael was kind enough to answer a few questions by email:

* * *

Harris: You appear to believe, as I do, that morality can (and should) arise out of a concern for the well-being of conscious creatures. But this normative claim is distinct from an evolutionary account of how we came to have moral emotions and preferences in the first place. It seems to me that there are two worthy, but distinct, scientific projects: (1) understanding how we got here and (2) understanding how to maximize our well-being going forward. Both projects are based on facts—facts about how we evolved, and facts about how conscious minds like our own can flourish in this universe. I’m wondering if you agree with this distinction and whether you have any further thoughts about the role science can play in deciding questions of right and wrong and good and evil.

Shermer: The criterion I use—inspired by your starting point in The Moral Landscape of “the well-being of conscious creatures”—is “the survival and flourishing of sentient beings.” By survival I mean the instinct to live, and by flourishing I mean having adequate sustenance, safety, shelter, bonding, and social relations for physical and mental health. I am trying to make an evolutionary/biological case for starting here by arguing that any organism subject to natural selection—which includes all organisms on this planet and most likely on any other planet as well—will by necessity have this drive to survive and flourish. If it didn’t, it would not live long enough to reproduce and would therefore not be subject to natural selection.

By sentient I mean emotive, perceptive, sensitive, responsive, conscious, and therefore able to feel and to suffer. Here I’m following the argument made by Jeremy Bentham with regard to animals: It isn’t their intelligence, language, tool use, or reasoning power that should elicit our moral concerns, but their capacity to feel and suffer. To this I add the recent Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness—issued by an international group of prominent cognitive neuroscientists, neuropharmacologists, neuroanatomists, and computational neuroscientists—that there is continuity between humans and non-human animals, and that sentience is the common characteristic across species.

When I talk about a moral arc of progress, I mean an improvement in the survival and flourishing of individual sentient beings. I emphasize the individual for four reasons: (1) Natural selection operates on individual organisms, not groups (see Steven Pinker’s dismantling of group selection arguments here.). (2) It is the individual who is the primary moral agent—not the group, tribe, race, gender, state, nation, empire, society, or any other collective—because it is the individual who survives and flourishes, or who suffers and dies. It is individual sentient beings who perceive, emote, respond, love, feel, and suffer—not populations, races, genders, groups, or nations. (3) Historically, immoral abuses have been most rampant, and body counts have run the highest, when the individual is sacrificed for the good of the group. It happens when people are judged by the color of their skin—or by their X/Y chromosomes, or by whom they prefer to sleep with, or by what accent they speak with, or by which political or religious group they belong to, or by any other trait our species has chosen to differentiate among members—instead of by the content of their individual character. (4) The rights revolutions of the past two centuries have focused almost entirely on the freedom and autonomy of individuals, not collectives—on the rights of persons, not groups. Individuals vote, not races or genders. Individuals want to be treated equally, not races. Rights protect individuals, not groups; in fact, most rights (such as those enumerated in the Bill of Rights) protect individuals from being discriminated against as members of a group, such as by race, creed, color, gender, or—soon—sexual orientation and gender preference.

In this sense, my argument is one for natural rights. I know that Bentham called “rights” nonsense and “natural rights” nonsense on stilts, but he came before Darwin and all the rights revolutions.

Also following your lead in The Moral Landscape, in which you make the argument that if one agrees that it is better to be healthy than to have cancer (a physical health analogy), I employ a public health analogy. I argue that if you agree that it is better that millions of people no longer die of yellow fever and smallpox, cholera and bronchitis, dysentery and diarrhea, consumption and tuberculosis, measles and mumps, gangrene and gastritis, and many other assaults on the human body that hardly even enter our conscious awareness today, then you have offered your assent that the way something is (diseases such as yellow fever and smallpox kill people) means we ought to prevent it through vaccinations and other medical and public health technologies.

By extension, I then make the case that social problems such as homicide and violence ought to be—and in fact are—treated as public health issues. Over the centuries the rates of violence in general and homicide in particular have plummeted, primarily as a result of better governance, better policing, and numerous other social policies grounded in reasoned arguments and empirical data. If you agree that millions of lives have been saved over the past couple of centuries by a reduction in violence due to improved technologies and policies, then you might well concur that applying the methods of the social sciences to solving problems such as crime and violence is also something we ought to do.

Why? Because saving lives is moral. Why is saving lives moral? Because the survival and flourishing of sentient beings is our moral starting point.

Harris: Clearly, some people have strongly felt convictions that they consider “moral”—disgust at the very idea of homosexuality, say—which we would consider pseudo-moral, in that they are based on dogmas and taboos that fail to align with a truly rational approach to maximizing human flourishing. Do you think we are making progress in reducing this kind of moral confusion?

Shermer: If you believe that the cavorting of women with demons in the middle of the night causes bad weather, crop failures, diseases, accidents, and assorted other maladies, then either you are insane or you lived 500 years ago, when almost everyone accepted the witch theory of causality, and burning women at the stake was considered to be a moral good in the name of improving the community. The people who torched women were not so much immoral as mistaken. They undoubtedly truly believed that what they were doing was right and good, but their actions were grounded in an incorrect understanding of causality.

Today we no longer accept the witch theory of causality because science debunked it. In its stead science created natural and more accurate explanations for such phenomena as weather and diseases. Science has also debunked other superstitious beliefs, such as demon possession; the need for animal and human sacrifice to appease God; that Jews caused the Black Death; that African Americans are an inferior race; that women are the weaker gender; that animals do not suffer, so it’s okay to harm or eat them; and—to your question—that homosexuals have a “gay lifestyle” or “gay agenda” that they want to force on straights and that will corrupt the morals of the youth.

With the exception of psychopaths and sadists, who seem to enjoy harming others, most people act in what they consider to be moral ways, so when we can clearly see (and measure) that they are in fact behaving in ways that lead to the suffering or death of sentient beings, it is probably more accurate to say that they are mistaken in their beliefs than that they are simply immoral or evil. And the solution is not so much that we need to make them more moral as it is that we need to correct their mistaken beliefs. Science and reason are the best tools we have for doing just that, so ultimately moral progress comes about from generating better ideas rather than better morality.

Harris: What role has religion played in our moral progress?

Shermer: I like to paraphrase Winston Churchill in his description of Americans: You can always count on religions to do the right thing…after they’ve tried everything else. It’s true that the abolition of slavery was championed by Quakers and Mennonites, that the civil rights movement was led by a Baptist preacher named Martin Luther King Jr., and that gay rights and same-sex marriage were backed early on by some Episcopalian ministers. But these are the exceptions, and for the most part people who opposed abolition, civil rights, and gay marriage were (and still are, in the latter case) their fellow Christians. In my debates with Dinesh D’Souza, he holds up William Wilberforce—the British abolitionist—as an example of how religion drives moral progress. But when I looked into that history a bit more carefully, it turns out that Wilberforce’s opponents in Parliament were all his fellow Christians, who justified slavery with religious and Bible-based arguments. (Plus, as I note in my book, “Wilberforce’s religious motives were complicated by his pushy and overzealous moralizing about virtually every aspect of life, and his great passion seemed to be to worry incessantly about what other people were doing, especially if what they were doing involved pleasure, excess, and ‘the torrent of profaneness that every day makes more rapid advances.’”)

The gay rights revolution we’re undergoing right now is a case study in how rights revolutions come about, because we can see who supports it and who opposes it: The vast majority of conservative and fundamentalist Christians have opposed (and still do oppose) same-sex marriage and equal rights for gays, whereas secularists and non-religious people support the movement; and those religious people who do endorse same-sex marriage are members of the most liberal and the least dogmatic sects.

So, while I acknowledge that many religious people do much good work in the world, manning soup kitchens and providing aid to the poor and disaster relief to those in temporary need, religions overall have lagged behind the moral arc, sometimes for an embarrassingly long time.

Harris: Where do you think we are headed? Is moral progress nearly inevitable at this point, or is serious moral decline a real possibility?

Shermer: I’m optimistic for the future. I titled the final chapter of The Moral Arc “Protopia,” in contrast to unrealistic utopias and dystopias. The word was coined by the futurist Kevin Kelly, founder of Wired magazine, who tracks trends in science, technology, and society. Protopia consists of gradual, steady, stepwise improvements in humanity. Today is ever so slightly better than yesterday, and tomorrow will be ever so slightly better than today, and so on. The moral arc is not a smooth curve—there are periodic setbacks such as ISIS/ISIL, Syria, and Putin—and it is not impossible that something like a global nuclear exchange could lurch us back into barbarism, but it is highly unlikely. No terrorist organization has ever overturned the government of a state and established its own. Putin will never reconstruct a Russian empire on par with the USSR. The taboo against using nuclear weapons is stronger than ever before, and it’s now even shifting toward possessing nuclear weapons. The chances, say, that the French will ever march through the Chunnel and advance on London to conquer England are so remote as to be almost laughable. I seriously doubt that the nations of the world will change their minds about slavery and make it legal again, or disenfranchise blacks and women, or reinstitute the death penalty for such petty crimes as shoplifting or insulting the king.

I believe that the moral progress we have made is real and lasting. We can do a lot more, to be sure, and there will always be episodes of violence and other setbacks on the protopian journey, but the long-term trends are extremely encouraging, and we have many good reasons for optimism about the future of humanity.

January 25, 2015

On My Radar: Sam Harris’s Cultural Highlights

By Kathy Sweeney

The neuroscientist, author and philosopher on the Tesla Model S, Brazilian jiujitsu and his fear that the machines will take over…

January 21, 2015

January 16, 2015

Can We Avoid a Digital Apocalypse?

(Photo via Armand Turpel)

It seems increasingly likely that we will one day build machines that possess superhuman intelligence. We need only continue to produce better computers—which we will, unless we destroy ourselves or meet our end some other way. We already know that it is possible for mere matter to acquire “general intelligence”—the ability to learn new concepts and employ them in unfamiliar contexts—because the 1,200 cc of salty porridge inside our heads has managed it. There is no reason to believe that a suitably advanced digital computer couldn’t do the same.

It is often said that the near-term goal is to build a machine that possesses “human level” intelligence. But unless we specifically emulate a human brain—with all its limitations—this is a false goal. The computer on which I am writing these words already possesses superhuman powers of memory and calculation. It also has potential access to most of the world’s information. Unless we take extraordinary steps to hobble it, any future artificial general intelligence (AGI) will exceed human performance on every task for which it is considered a source of “intelligence” in the first place. Whether such a machine would necessarily be conscious is an open question. But conscious or not, an AGI might very well develop goals incompatible with our own. Just how sudden and lethal this parting of the ways might be is now the subject of much colorful speculation.

One way of glimpsing the coming risk is to imagine what might happen if we accomplished our aims and built a superhuman AGI that behaved exactly as intended. Such a machine would quickly free us from drudgery and even from the inconvenience of doing most intellectual work. What would follow under our current political order? There is no law of economics that guarantees that human beings will find jobs in the presence of every possible technological advance. Once we built the perfect labor-saving device, the cost of manufacturing new devices would approach the cost of raw materials. Absent a willingness to immediately put this new capital at the service of all humanity, a few of us would enjoy unimaginable wealth, and the rest would be free to starve. Even in the presence of a truly benign AGI, we could find ourselves slipping back to a state of nature, policed by drones.

And what would the Russians or the Chinese do if they learned that some company in Silicon Valley was about to develop a superintelligent AGI? This machine would, by definition, be capable of waging war—terrestrial and cyber—with unprecedented power. How would our adversaries behave on the brink of such a winner-take-all scenario? Mere rumors of an AGI might cause our species to go berserk.

It is sobering to admit that chaos seems a probable outcome even in the best-case scenario, in which the AGI remained perfectly obedient. But of course we cannot assume the best-case scenario. In fact, “the control problem”—the solution to which would guarantee obedience in any advanced AGI—appears quite difficult to solve.

Imagine, for instance, that we build a computer that is no more intelligent than the average team of researchers at Stanford or MIT—but, because it functions on a digital timescale, it runs a million times faster than the minds that built it. Set it humming for a week, and it would perform 20,000 years of human-level intellectual work. What are the chances that such an entity would remain content to take direction from us? And how could we confidently predict the thoughts and actions of an autonomous agent that sees more deeply into the past, present, and future than we do?

The fact that we seem to be hastening toward some sort of digital apocalypse poses several intellectual and ethical challenges. For instance, in order to have any hope that a superintelligent AGI would have values commensurate with our own, we would have to instill those values in it (or otherwise get it to emulate us). But whose values should count? Should everyone get a vote in creating the utility function of our new colossus? If nothing else, the invention of an AGI would force us to resolve some very old (and boring) arguments in moral philosophy.

However, a true AGI would probably acquire new values, or at least develop novel—and perhaps dangerous—near-term goals. What steps might a superintelligence take to ensure its continued survival or access to computational resources? Whether the behavior of such a machine would remain compatible with human flourishing might be the most important question our species ever asks.

The problem, however, is that only a few of us seem to be in a position to think this question through. Indeed, the moment of truth might arrive amid circumstances that are disconcertingly informal and inauspicious: Picture ten young men in a room—several of them with undiagnosed Asperger’s—drinking Red Bull and wondering whether to flip a switch. Should any single company or research group be able to decide the fate of humanity? The question nearly answers itself.

And yet it is beginning to seem likely that some small number of smart people will one day roll these dice. And the temptation will be understandable. We confront problems—Alzheimer’s disease, climate change, economic instability—for which superhuman intelligence could offer a solution. In fact, the only thing nearly as scary as building an AGI is the prospect of not building one. Nevertheless, those who are closest to doing this work have the greatest responsibility to anticipate its dangers. Yes, other fields pose extraordinary risks—but the difference between AGI and something like synthetic biology is that, in the latter, the most dangerous innovations (such as germline mutation) are not the most tempting, commercially or ethically. With AGI the most powerful methods (such as recursive self-improvement) are precisely those that entail the most risk.

We seem to be in the process of building a God. Now would be a good time to wonder whether it will (or even can) be a good one.

—

Read the other responses at Edge.org

December 16, 2014

The Very Bad Wizards Interview #1

0:00-47:00—Intro and costs and benefits of religion

47:00-1:17:00—Drugs, the self, free will

1:17:30-end—Blame, guilt, vengeance, moral responsibility

David Pizarro is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY. His primary research interest is in how and why humans make moral judgments, such as what makes us think certain actions are wrong, and that some people deserve blame. In addition, he studies how emotions influence a wide variety of judgments. These two areas of interest come together in the topic of much of his recent work, which has focused on the emotion of disgust and the role it plays in shaping moral, social, and political judgments.

Tamler Sommers is an associate professor in the Philosophy Department at the University of Houston with a joint appointment in the Honors College. He is director of the Honors minor Phronesis: A Program in Politics and Ethics. His research focuses on issues relating to moral responsibility, criminal justice, honor, and revenge. Sommers is the author of two books: Relative Justice: Cultural Diversity, Free Will, and Moral Responsibility (Princeton, 2012) and A Very Bad Wizard: Morality Behind the Curtain (McSweeney’s, 2009). He received his PhD in Philosophy from Duke University in 2005.

December 5, 2014

Petition All You Want, Bill Maher Will Speak at Berkeley

December 3, 2014

The Frontiers of Secularism

Phil Zuckerman is a professor of sociology and secular studies at Pitzer College in Claremont, California. He is also a regular affiliated professor at Claremont Graduate University, and he has been a guest professor for two years at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. He is also a Fellow of the Secular Global Institute.

Zuckerman is the author of Living the Secular Life, Faith No More, and Society Without God. He has also edited several volumes, including Atheism and Secularity, Sex and Religion, and The Social Theory of W.E.B. Du Bois. Zuckerman writes a regular blog for Psychology Today titled “The Secular Life,” and he also writes for the Huffington Post. His work has also been published in academic journals, such as Sociology Compass, Sociology of Religion, Deviant Behavior, and Religion, Brain, and Behavior.

In 2011, Zuckerman founded the first Secular Studies department in the nation. Secular Studies is an interdisciplinary program focusing on manifestations of secularism in societies and cultures, past and present. Secular Studies entails the study of non-religious people, groups, thought, and cultural expressions. Emphasis is placed upon the meanings, forms, relevance, and impact of political/constitutional secularism, philosophical skepticism, and personal and public secularity. Zuckerman earned his PhD in sociology from the University of Oregon in 1998. He currently lives in Claremont, California, with his wife, Stacy, and their three children.

* * *

Harris: Your most recent book is Living the Secular Life, and you founded the secular studies program at Pitzer College. Perhaps we should begin by clarifying what “secularism” is, because many people use it as a synonym for “atheism,” which it isn’t.

Zuckerman: I’m going to resist the urge to whip out all my lecture notes, because this stuff is central to what I teach, and I’ve got a lot to say here. But I’ll try to be as brief and concise as I can.

We’ve got three terms that are closely related, but also distinct.

First off, let’s start with “secular.” To me, that simply means “non-religious.” In a nutshell, I’d say someone is secular if 1) he or she does not hold any supernatural beliefs about deities, spirits, or netherworlds 2) he or she does not engage in any religious rituals or rites, and 3) he or she does not identify or affiliate with a religious group, denomination, or tradition.

Next comes “secularization.” This term refers to a historical process whereby a given society becomes less religious over time: Fewer people hold religious beliefs, fewer people place importance on religious rituals or rites, fewer people identify as religious, fewer institutions exist under the auspices of religious authorities, and so on.

Finally, what you asked about: “secularism.” For me, the “ism” is key here. It implies ideology. Social movement. Political agenda. How things “ought” to be.

On this front, we’ve primarily got good, old-fashioned Jeffersonian secularism, which at root is nothing more than the ideology or political position that church and state ought to be separate and that government ought to be as neutral as possible when it comes to religion in the public square. This version of secularism is basically anti-theocracy-ism (or what used to be called disestablishmentarianism). It is an ideology that is often embraced by both religious and secular people. And it most definitely is not the same thing as “atheism.” In this instance, “secularism” is a political or ideological position concerning the relationship between government and religion (keep them separate!), whereas “atheism” is a personal absence of belief in gods.

Harris: Yes, it was the Jeffersonian sense of the term I had in mind, and I think that’s the meaning worth emphasizing. Secularism in this sense does not require unbelief. It merely demands a commitment to keeping religion out of politics and public policy. Secularism is the only viable response to religious pluralism—otherwise incompatible religions will vie for political dominance. Secularism, essentially, is a condition of permanent truce.

Zuckerman: I totally agree. But there is definitely another popular form or manifestation of secularism—one that is much less focused on the separation of church and state. This form is about people and groups actively trying to disabuse other people of their religious beliefs or involvement. It is a secularism that actively seeks to combat and critique religion. It is predicated upon the view that religion ought to go away, that religious beliefs ought not to be believed in anymore, that religion is a harmful thing and society would be generally better off if it just went away. Think of the 1980s hit “Dear God,” by XTC. That song wasn’t advocating for the separation of church and state. Rather, it was trying to get its listeners to agree that believing in God is silly or absurd. Or think of your first book, The End of Faith, which is not a detailed defense of the separation of church and state but primarily about exposing the irrational, malevolent, and harmful aspects of religion. This form of secularism—as exemplified by XTC’s song and your first book—is definitely not the same thing as “atheism,” per se, but it comes fairly close: Most secularists who actively seek to make religion go away and want to disabuse other people of their supernatural beliefs are atheists.

Harris: Can you summarize the current commitment to secularism in the West? Is it increasing?

Zuckerman: In certain parts of the West—particularly Europe, Australia, and Canada—secularism is going strong. However, in other places, including the USA, the situation is much less clear-cut.

In terms of political secularism, we see many instances in which the realms of religion and government are becoming more clearly and strongly divided. For example, Sweden officially disestablished religion from government in 2000. And in Britain, challenges to religious involvement in the public schools are growing. In Israel, there is increasing opposition to the governmental support of religious institutions and to the ability of religious fundamentalists to opt out of compulsory military service. In France, the separation of church and state is widely celebrated, and restrictions on religion in the public sphere are increasing.

However, here in the United States, the wall of separation between church and state is becoming less secure, especially in light of recent court decisions. I’m thinking specifically of some cases decided in 2014: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that closely held, for-profit corporations can claim exemption from laws that go against their owners’ religious beliefs. It also decided that kicking off city council meetings with explicitly sectarian Christian prayers is constitutional. Even the Massachusetts Supreme Court declared that the teacher-led, God-centric language of the Pledge of Allegiance doesn’t discriminate against the children of non-theists.

In other ways, however, the kind of secularism that involves weakening religious faith or lessening the strength, prestige, and pervasiveness of religion in society has been incredibly successful in the West, even here in the USA.

I don’t want to barrage you with endless numbers, but the stats are staggering when it comes to people in the West who are abandoning religion. Consider just these tidbits: A century ago in Canada, only 2% of the population claimed to have no religion, whereas today nearly 30% of Canadians claim as much, and approximately one in five does not believe in God. A century ago in Australia, less than 1% of the population claimed no religious identity, but today approximately 20% of Australians claim as much. A century ago in Holland, about 10% of the population claimed to be religiously unaffiliated; today more than 40% does. In contemporary Great Britain, nearly half the people claim no religious identity at all; the same is true in Sweden.

Furthermore, 61% of Czechs, 49% of Estonians, 45% of Slovenians, 34% of Bulgarians, and 31% of Norwegians do not believe in God. And 33% of the French, 27% of Belgians, and 25% of Germans do not believe in God or any other sort of universal spiritual life force.

In the East, the most recent survey information from Japan illustrates extensive secularization over the course of the past century: Sixty years ago, about 70% of Japanese people claimed to hold personal religious beliefs, but today that figure is down to about 20%. Such levels of atheism, agnosticism, and overall irreligion are simply remarkable—not to mention historically unprecedented.

I just got the latest data on Latin America: 37% of people in Uruguay, 18% in the Dominican Republic, 16% in Chile, 11% in Argentina, and 8% in Brazil are non-religious. These are all unprecedented levels of secularity. And Jamaica is currently at 20% nonreligious! Gabon and Swaziland are at 11%! (While that may seem small, keep in mind that only 8% of people in Alabama are non-religious).

Secularism is growing in virtually all nations for which we have data; even the Muslim world, which contains the most-religious societies on earth, has a growing share of secular people (many of whom, unfortunately, must keep their secularity well hidden because of the danger of prison or death for being open about their lack of faith).

The proportion of Americans walking away from religion has continued to grow, from 8% in 1990 to somewhere between 20% and 30% today. Secularity is markedly stronger among young Americans: 32% of those under 30 are religiously unaffiliated. And somewhere between one-third and one-half of all those who respond “none” when asked what their religion is are atheist or agnostic in orientation—so the rise of irreligion means a simultaneous rise of atheism and agnosticism. Furthermore, the vast majority of nonreligious Americans are content with their current identity; among those who now claim “none” as their religion, nearly 90% say they have no interest in looking for a religion that might be right for them.

Of course, one wrench in all this is birthrates. Religious people have more kids than secular people. So demographically, the future is unclear.

Harris: Many of us have acknowledged that “replacing religion” may not be an appropriate goal, religion does offer people many things they want in life—and these are things that most atheists also want. We want nice buildings that function as dedicated spaces for reflection and celebration. We want strong communities. We want rituals and rites of passage with which to mark important transitions in life—births, marriages, deaths. We just don’t want to lie to ourselves about the nature of reality to have these things. This poses a real challenge, because once we get rid of religion, we are left without an established tradition for meeting these needs, and the alternative is often piecemeal, halfhearted, and unsatisfying. How do you see us solving the problem of creating strong secular institutions and traditions that don’t feel hokey?

Zuckerman: You are spot-on here. Religion provides so much for people in terms of social capital, life-cycle rituals, and so forth, and if it were to just go away, most people would experience serious lacuna. True, a few die-hard hermits out there want none of the things that religion provides, but they are quite rare. Most people want and enjoy at least some of the many things that religions have to offer, even if they don’t buy all the supernatural nonsense.

So here are the options, as far as I can tell:

First, secularize religion. By that I mean keep the rituals, the holidays, the buildings, the gatherings, the knickknacks, but let the supernatural beliefs wither and fade. The example of this that first comes to mind is Reform Judaism. Most American Jews get what they like out of Judaism—the ceremonies, the holidays, the sense of belonging, multi-generational connections, opportunities for charity—and yet they have jettisoned the supernatural beliefs. Many liberal Episcopalian congregations, too, are in this vein. Also Quaker meetings. And most Scandinavians, with their modern form of Nordic Lutheranism, are as well. They observe traditional religious holidays and they participate in various life-cycle rituals and they congregate now and then in church and they even “feel” Christian—and yet they do all these ostensibly religious things without a scintilla of actual faith in the supernatural.

Personally, I think it would be great to have Catholicism, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, etc. all existing here and there, but neutered of their supernatural hoo-hah. I know that may seem contradictory or absurd, but I believe it is possible.

The second option is to create humanist congregations, like Sunday Assembly. The disadvantage here is that you are basically starting from nothing, which feels a little weird—there is no heritage, no tradition, no sense of something that has been around for generations. Not much for kids. But the advantage is that you get to create what you want and how you want it. I dig Sunday Assembly. I think the possibilities for such groups are strong. Obviously, they don’t appeal to most secular people—but for those who want the best of religious affiliation without all the supernaturalism, it is a damned viable option.

A third possibility is to find secular vehicles that provide at least some of the things religion has to offer. I’m thinking of sports, for example. Soccer. My Sunday morning soccer game fulfills me deeply: It makes me feel alive, it connects me to friends I otherwise would never know or see, it marks the end of the week, etc. Or music. My daughter’s love of music provides a lot: a sense of existential meaning, a sense of community via links with other fans, rituals in the form of concerts, and so forth. My younger daughter’s involvement in ballet serves a similar function, providing self-improvement, conscientiousness, camaraderie, performances. Others can find at least some of the things religion offers by communing with nature, or being creative, or engaging politically, or meditating.

I have learned in my research that the vast majority of people who walk away from religion don’t miss it and find numerous ways to live meaningful lives without it—through work, family life, friends, hobbies, art, sex, philosophy, theater, hunting, working on cars, dancing, and so on.

Of course, all that said, religion may not be so easily replaced, and the fact that secularism seems to correlate strongly with individualism could become a problem down the road.

Harris: Moving beyond religion is an immense challenge, and I greatly appreciate your contributions on this front. One of the main impediments to the spread of secularism has been the widely and lazily held belief, even among the non-religious, that religion will always be with us—as though the persistence of the current batch of supernatural ideas were a law of nature. I hope people will read your book to learn more about what the transition to secularism will look like. Thanks for taking the time to speak with me.

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9007 followers