Sam Harris's Blog, page 18

November 4, 2014

October 28, 2014

The Path and the Goal

(Photo via Mitchell Joyce)

Joseph Goldstein has been leading meditation retreats worldwide since 1974. He is a cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society, the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, and the Forest Refuge. Since 1967, he has practiced different forms of Buddhist meditation under eminent teachers from India, Burma, and Tibet. His books include The Experience of Insight, A Heart Full of Peace, One Dharma, and Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening. For more information about Joseph, please visit www.dharma.org.

Joseph has been a close friend for more than 20 years. He was one of my first meditation teachers and remains one of the wisest people I have ever met. In this two-hour conversation, we discuss how he came to devote his life to the study of meditation. We also debate some of the finer points of the practice.

Although parts of this discussion are accessible, much of it is quite esoteric. I suspect that only experienced meditators will find the second half interesting, or even intelligible. My latest book, Waking Up, provides some necessary context, but there is no substitute for time spent engaging these practices on retreat.—SH

October 23, 2014

The Young Turks Interview

I recently sat down with Cenk Uygur of The Young Turks to discuss my most controversial views about Islam, the war on terror, and related topics. It was, of necessity, a defensive performance on my part—more like a deposition than an ordinary conversation. Although it was a friendly exchange, there were times when Cenk appeared to be trying very hard to miss my point. Rather than rebut my actual views (or accept them), he often focused on how a misunderstanding of what I was saying could lead to bad outcomes—as though this were an argument against my views themselves. However, he did provide a forum in which we could have an unusually full discussion about difficult issues. I hope viewers find it useful.

Having now watched the full exchange, I feel the need to expand on a couple of points:

Journalistic Ethics

The passage of journalism into its digital future is proving more than a little perilous. We seem to be circling a vortex, at the bottom of which lies the perennial problem of money: How can writers, editors, and publishers get paid for their work? I can’t help but feel that a reliance on advertising is encouraging the worst instincts in everyone involved. There is comedy to be found here, of course. I recently came across an article accusing me of “sexism” that was paid for by ads promising access to “Sexy Asian Brides.” However, the results of any system of bad incentives are rarely amusing. We must find some way to correct course.

I began my conversation with Cenk by complaining about how he had treated me on his show in the previous weeks. I think his unwillingness to acknowledge the difference between valid criticism and misrepresentation was a missed opportunity (for him). He seems to believe that allowing a target of defamation to give his or her side of the story provides the necessary balance. He also detects an ethical symmetry where none exists: If writer X has been spreading malicious lies about writer Y, and Y accurately describes X as “a liar,” that does not give each party an equivalent grievance against the other. Cenk seems to view most claims of misrepresentation as a he-said-she-said stalemate that is, in principle, impossible to resolve.

This is a growing problem in journalism. In my conversation with Cenk, I briefly discussed Salon’s unethical treatment of me, but I’ve had many other encounters with journalists and editors that should trouble readers.

For instance, I recently discussed an incident in which Glenn Greenwald forwarded a tweet describing me as “genocidal fascist maniac” (Reza Aslan did the same). Feeling that these attacks had gone on long enough, I decided to call John Cook, the editor in chief at the Intercept.

Here is a snippet of our conversation:

Me: My criticism of Islam is not racist.

Cook: It is racist.

Me: John, Islam is not a race. You can’t convert to a race. And my criticism of Islam applies to white converts just as much as it does to Arabs or anyone else born in a Muslim country. In fact, it applies to converts more because they weren’t brainwashed into the faith from birth.

Cook: So all Arabs are brainwashed?

Me: What?

Cook: You just said “Arabs are brainwashed.” That’s racist.

Me: I was just making a point about the difference between having an ideology drummed into you from birth and converting to it as an adult who may have had the benefit of an Oxford education! These are different cases. And I am less judgmental of the former.

The conversation continued like this for 40 minutes. I felt like I was talking to a robot programmed to run a reason-destroying, political-correctness routine until the end of the world. It was, in fact, the most maddening encounter I’ve had with another human being in decades. I actually hung up on the man. (I haven’t done that since high school.)

I have no idea what Cook’s background is, but this is not a person who should be guiding journalism into its digital future. The only ethical defense he could give me for Greenwald’s retweeting defamatory nonsense about me (again, calling me a “genocidal fascist maniac”) was that “everyone knows that retweets don’t equal endorsements”—as if this were some high principle of journalistic ethics. Of course, in this case it was an endorsement. Greenwald has repeatedly described me as a dangerous bigot in print and on social media—and reaffirming this negative impression of me was the whole point of his passing this tweet along to his 420,000 followers.

What makes Cook’s precarious hold on journalistic integrity so ominous is that he, Greenwald, and colleagues have been given $250 million in funding from Pierre Omidyar. This is a fantastic sum of money—indeed, it is the same amount that Jeff Bezos recently paid for the Washington Post. It is difficult to see how this bodes well for the future of journalism.

It is also important to observe how social media is facilitating this race to the bottom. For instance, one of my critics on Twitter recently misrepresented my views about the distinction between what is “natural” and what is “good.” When discussing this difference, I often say things like “There is nothing more natural than rape: orangutans do it; dolphins do it; and people do it.” But the next words out of my mouth are always something like, “But no one would argue that rape is good, or compatible with a civil society, because it may have had evolutionary advantages for certain species. Rape is one of the most immoral behaviors there is.” Perhaps you can guess how this person summarized my views about rape for his 10,000 followers: In a series of tweets he represented me as someone who sees no moral problem with rape at all, because it is a perfectly “natural,” biological imperative.

When I complained about this on Twitter, here is what Murtaza Hussain, Greenwald’s colleague at the Intercept, tweeted: “You’re going to have to come to grips w/ the fact that no ones misinterpreting you—you just have monstrous views.” Needless to say, Hussain has written multiple articles attacking me as a racist, warmonger, and “Islamophobe.”

Here is the most charitable interpretation I can make of this behavior: People like Greenwald and Hussain are so sure that they are on the right side of important issues that, when they see someone whom they imagine to be on the wrong side, they feel justified in distorting his views in an effort to destroy his credibility. This is an all-too-human impulse, of course, but it is extraordinarily destructive behavior in “journalists.”

Correcting an Error of My Own

Given how maliciously he has misrepresented me (and how much I have complained about it), it is very unfortunate that I seem to have spoken misleadingly about Greenwald’s attitude toward collateral damage at the end of my conversation with Cenk.

I did not mean to suggest that Greenwald is insensitive to the reality of collateral damage. I meant to say that in his vilification of me for my discussion of torture, he has ignored that my argument is based on my own concern for collateral damage. Given his penchant for defamation and his disinclination to follow careful arguments, he has helped make it nearly impossible to discuss these issues in a public forum. But my point did not come across at all well, and I seemed to suggest either that Greenwald is, like many people, unaware of how horrible collateral damage is or that he does not care about it. Anyone familiar with Greenwald’s work will know that either charge is ludicrous. (If anything, he is too sensitive to collateral damage, and this clouds his thinking about U.S. foreign policy, jihadism, and related matters.)

October 20, 2014

Just the Facts

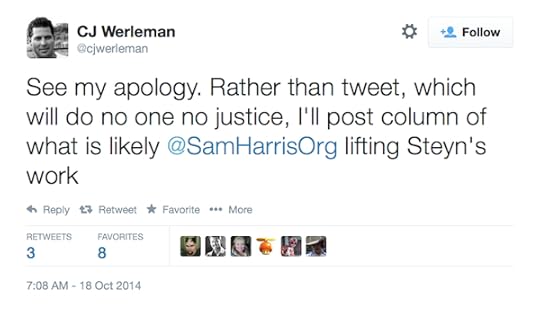

1. C.J. Werleman, a writer for Salon and Alternet, has made a habit of publicly misrepresenting my views.

2. When I first noticed this behavior, I contacted him, initiating a brief and unpleasant email exchange.

3. After that exchange, Werleman went on to misrepresent my views with even greater fervor.

4. Werleman was subsequently discovered to be a serial plagiarist.

5. His response to this public humiliation was to accuse me of being a plagiarist too. Specifically, I am alleged to have plagiarized the work of Mark Steyn.

6. Evidence for this charge has been presented on a blog that seems to have been created yesterday for this purpose by “Stephanie Cranson” (who also joined Twitter only yesterday). Note that this is two days after Werleman claimed to have knowledge of my stealing Steyn’s work. I shall let readers make of this timeline what they will.

7. This newborn blogger has noticed that a passage in Letter to a Christian Nation (2006) seems suspiciously similar to one in Steyn’s book America Alone (2006)—which, we are told, was published six months earlier.

8. However, the suspicious passage also appears in my first book, The End of Faith, published two years earlier still (2004). It can be found on page 26 of both the hardcover and paperback editions.

9. Another passage I am alleged to have plagiarized from Steyn also appears in The End of Faith (p. 133). For that, I cited the following source in an endnote: “From the United Nations’ Arab Human Development Report 2002, cited in Lewis, Crisis of Islam, 115–17.”

10. “Stephanie Cranson” makes other allegations on “her” blog that are equally unfounded. For instance, she claims that I plagiarized from my friend Richard Dawkins, on the basis of similarity between the following passages:

Dawkins: “Although Martin Luther King was a Christian, he derived his philosophy of non-violent civil disobedience directly from Gandhi, who was not.”

Harris: “While King undoubtedly considered himself a devout Christian, he acquired his commitment to non-violence primarily from the writings of Mohandas K. Gandhi.”

The Dawkins quote appears on page 307 of The God Delusion. Mine can be found on page 12 of Letter to a Christian Nation. As readers can learn on Amazon, these books were published a day apart in September of 2006. And, needless to say, this observation about King’s debt to Gandhi has been made many, many times before.

11. This will be the last thing I ever write about C.J. Werleman.

Email Exchange Between Sam Harris and C.J. Werleman

CJ Werleman tweeted “Sam Harris is the Pat Robertson of atheism” to his 10,000 followers and linked to a libelous article entitled “Sam Harris Slurs Malala” (I had actually written that Malala deserved the Nobel Peace Prize and that she was the best thing to come out of the Muslim world in a thousand years). So I contacted Werleman, initiating the following exchange:

October 21, 2013 9:24 AM

Interesting, CJ. Did you actually read my blog post, or just the Salon hit piece?

Sam

****

Oct 21, 2013, at 9:46 AM

Hi Sam,

No, I didn’t read your blog. Having said that, I actually disagreed with much of the Salon piece. In fact, I think it spun your words to serve its own agenda.

My disagreement is with your broader position on Islamic terrorism. I believe it’s motivated purely by political objective. You believe it starts and ends with religious fundamentalism, and whether you intend to or not, it makes us atheists sound eerily similar to those who speak from the right wing echo chamber.

Obviously, that’s harsh criticism given your service to atheism. You have liberated millions of minds, and I count myself as one of your fans. But on the subject of Islam, I believe you miss the point. It’s a travesty, because you have the influence to change minds and foreign policy….but your comments get used to justify neo-conservatism.

I appreciate your note.

Cheers

CJ

****

October 21, 2013 at 11:05 AM

Incredible… You brand me the “Pat Robertson of atheism,” linking to this drivel on Salon and forwarding to thousands of people, without ever checking to see if the writer has misrepresented my views (which he has, in every relevant respect).

And then you want me to debate you?

****

October 21, 2013 at 11:18:30 AM

Ha, I see your point : )

I often err on the side of extreme rhetoric to make a point. Do I think you’re the PR of atheism? No. And I owe you an apology on that, and I have deleted that tweet. But the rhetoric that comes from those who lean towards an anti-Islam position over an anti-foreign policy position sounds a little PR/FOX/Coulter like, which ultimately serves to keep the country making poor errors of judgment when it comes to our use of the military.

CJ

****

Werleman subsequently wrote an article entitled “Atheist Authors Feud Over Islamic Extremism” based on the previous email exchange. He then wrote another piece suggesting that I and other atheists were oblivious to the problem of wealth inequality. Having written a fair amount about wealth inequality, I contacted him again:

October 26, 2013 11:06 PM

So I’ve been oblivious to the problem of wealth inequality? Really?

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sam-har...

http://www.samharris.org/blog/item/ho...

http://www.samharris.org/blog/item/ho...

****

Oct 27, 2013, at 4:31 PM

Hi Sam,

If you read the piece again, you will see I was specifically referring to the atheist movement’s lack of attention given to wealth inequality. Moreover, I defined the atheist movement not as individuals, authors or thought leaders, but rather as the 2,000+ atheist groups/organizations.

Cheers

CJ

****

October 27, 2013 5:13 PM

Oh, so you would expect readers of your piece to come away thinking that I’ve done my part on the problem of wealth inequality?

****

Oct 27, 2013, at 5:30 PM

Mate, the piece wasn’t about you. I didn’t say you hadn’t done your part on the problem of wealth inequality. I honored you for being one of the three luminaries whose books were the catalyst for launching the AM. My only other mention of you was in criticizing what I perceive to be your myopic view on the roots of terrorism.

CJ

****

October 27, 2013 at 7:14:30 PM

It’s remarkable that you think I’m being prickly and self-absorbed here. First, you retweet a libelous attack on me and brand me the Pat Robertson of atheism. When I confront you about this, you admit that you never took the time to read my original blog post. You then write an astonishingly self-serving piece in which you divulge the contents of my private email to you without my permission (do you really not know how uncool that is?) titled, “Atheist Authors Feud Over Islamic Extremism.” We’re feuding? I never heard of you until I read your tweet. And we’re not debating Islamic extremism—we’re talking about how callowly you’ve been sniping at me. (From what I can tell, you are completely deluded about Islamic extremism.) You then write another piece in which you again attack me by name, “honoring” me as one of the founders of the movement that has so scandalously ignored the problem of wealth inequality. When I show you that I’ve written three long articles on the topic, you dodge and put the onus on me: “Mate, the piece wasn’t about you.” Oh, I’m sorry. There goes my narcissism again.

My only purpose in engaging you has been to try to get you to recognize how unprofessional your behavior has been. This is a lesson you don’t seem willing to learn.

In any case, I’m done. Good luck. At this rate, you will need a lot of it.

Sam

October 15, 2014

What Does ‘Islamophobia’ Actually Mean?

October 12, 2014

On the Mechanics of Defamation

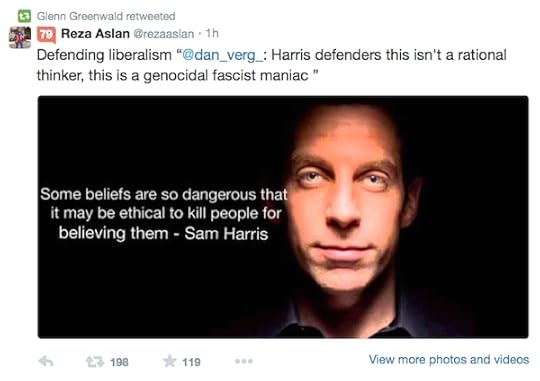

Let me briefly illustrate how this works. Although I could cite hundreds of examples from the past two weeks alone, here is what I woke up to this morning: Some person who goes by the name of @dan_verg_ on Twitter took the most easily misunderstood sentence in The End of Faith out of (its absolutely essential) context, attached it to a scary picture of me, and declared me a “genocidal fascist maniac.” Then Reza Aslan retweeted it. An hour later, Glenn Greenwald retweeted it again.

That took less than two seconds of their time, and the message was sent to millions of people. I know one thing to a moral certainty, however: Both Greenwald and Aslan know that those words do not mean what they appear to mean. Given the amount of correspondence we’ve had on these topics, and given that I have repeatedly bored audiences by clarifying that statement (in response to this kind of treatment), the chance that either writer thinks he is exposing the truth about my views—or that I’m really a “genocidal fascist maniac”—is zero. Aslan and Greenwald—a famous “scholar” and a famous “journalist”—are engaged in a campaign of pure defamation. They are consciously misleading their readers and increasing my security concerns in the process.

No matter how completely opposed I may have been to another person’s views, I have not behaved like that. I have never knowingly distorted the positions I criticize, whether they are the doctrines of a religion or the personal beliefs of Francis Collins, Eben Alexander, Deepak Chopra, Reza Aslan, Glenn Greenwald, or any other writer or public figure with whom I’ve collided. The crucial boundary between hard-hitting criticism and defamation is knowing that you are misrepresenting your target.

Here is the statement in context (p. 52−53):

The power that belief has over our emotional lives appears to be total. For every emotion that you are capable of feeling, there is surely a belief that could invoke it in a matter of moments. Consider the following proposition:

Your daughter is being slowly tortured in an English jail.

What is it that stands between you and the absolute panic that such a proposition would loose in the mind and body of a person who believed it? Perhaps you do not have a daughter, or you know her to be safely at home, or you believe that English jailors are renowned for their congeniality. Whatever the reason, the door to belief has not yet swung upon its hinges.

The link between belief and behavior raises the stakes considerably. Some propositions are so dangerous that it may even be ethical to kill people for believing them. This may seem an extraordinary claim, but it merely enunciates an ordinary fact about the world in which we live. Certain beliefs place their adherents beyond the reach of every peaceful means of persuasion, while inspiring them to commit acts of extraordinary violence against others. There is, in fact, no talking to some people. If they cannot be captured, and they often cannot, otherwise tolerant people may be justified in killing them in self-defense. This is what the United States attempted in Afghanistan, and it is what we and other Western powers are bound to attempt, at an even greater cost to ourselves and to innocents abroad, elsewhere in the Muslim world. We will continue to spill blood in what is, at bottom, a war of ideas.

There is an endnote to this passage that reads:

We do not have to bring the membership of Al Qaeda “to justice” merely because of what happened on Sept. 11, 2001. The thousands of men, women, and children who disappeared in the rubble of the World Trade Center are beyond our help—and successful acts of retribution, however satisfying they may be to some people, will not change this fact. Our subsequent actions in Afghanistan and elsewhere are justified because of what will happen to more innocent people if members of Al Qaeda are allowed to go on living by the light of their peculiar beliefs. The horror of Sept. 11 should motivate us, not because it provides us with a grievance that we now must avenge, but because it proves beyond any possibility of doubt that certain twenty-first-century Muslims actually believe the most dangerous and implausible tenets of their faith.

The larger context of this passage is a philosophical and psychological analysis of belief as an engine of behavior—and the link to behavior is the whole point of the discussion. Why would it be ethical to drop a bomb on the leaders of ISIS at this moment? Because of all the harm they’ve caused? No. Killing them will do nothing to alleviate that harm. It would be ethical to kill these men—once again, only if we couldn’t capture them—because of all the death and suffering they intend to cause in the future. Why do they intend this? Because of what they believe about infidels, apostates, women, paradise, prophecy, America, and so forth.

Aslan and Greenwald know that nowhere in my work do I suggest that we kill harmless people for thought crimes. And yet they (along with several of their colleagues) are doing their best to spread this lie about me. Nearly every other comment they’ve made about my work is similarly misleading.

Both Aslan and Greenwald are debasing our public discourse and making honest discussion of important ideas increasingly unpleasant—even personally dangerous. Why are they doing this? Please ask them and those who publish them.

October 9, 2014

The Diversity of Islam

October 8, 2014

Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History

From time to time one discovers a person so good at his job that it is almost impossible to imagine him doing anything else. I recently had this experience listening to Dan Carlin’s podcast Hardcore History. Carlin’s way of speaking is so in tune with his subject, and his enthusiasm so contagious, that one can’t help feeling he was born to do this work (think Rod Serling and The Twilight Zone).

Carlin is not a professional historian—just a “history geek” with an undergraduate degree in the subject—but he could well be the most engaging history professor on earth. His series on WWI is simply a masterpiece—made all the more impressive by the informal, meandering way he leads the listener from poignancy to horror and back again. Carlin is doing something truly extraordinary in this medium. He deserves a wide audience. And you deserve the pleasure of listening to him.

October 7, 2014

Can Liberalism Be Saved From Itself?

My recent collision with Ben Affleck on Bill Maher’s show, Real Time, has provoked an extraordinary amount of controversy. It seems a postmortem is in order.

For those who haven’t seen the show, most of what I write here won’t make sense unless you watch my segment:

So what happened there?

I admit that I was a little thrown by Affleck’s animosity. I don’t know where it came from, because we hadn’t met before I joined the panel. And it was clear from our conversation after the show that he is totally unfamiliar with my work. I suspect that among his handlers there is a fan of Glenn Greenwald who prepared him for his appearance by simply telling him that I am a racist and a warmonger.

Whatever the reason, if you watch the full video of our exchange (which actually begins before the above clip), you will see that Affleck was gunning for me from the start. What many viewers probably don’t realize is that the mid-show interview is supposed be a protected five-to-seven-minute conversation between Maher and the new guest—and all the panelists know this. To ignore this structure and encroach on this space is a little rude; to jump in with criticism, as Affleck did, is pretty hostile. He tried to land his first blow a mere 90 seconds after I took my seat, before the topic of Islam even came up.

Although I was aware that I wasn’t getting much love from Affleck, I didn’t realize how unfriendly he had been on the show until I watched it on television the next day. This was by no means a normal encounter between strangers. For instance: I said that liberalism was failing us on the topic of Islamic theocracy, and Affleck snidely remarked, “Thank God you’re here!” (This was his second interruption of my interview.) I then said, “We have been sold this meme of Islamophobia, where every criticism of the doctrine of Islam gets conflated with bigotry toward Muslims as people,” and Affleck jumped in for the third time, more or less declaring the mid-show interview over: “Now hold on—are you the person who understands the officially codified doctrine of Islam? You’re the interpreter of that?”

As many have since pointed out, Affleck and Nicholas Kristof then promptly demonstrated my thesis by mistaking everything Maher and I said about Islam for bigotry toward Muslims. Our statements were “gross,” “racist,” “ugly,” “like saying you’re a shifty Jew” (Affleck), and a “caricature” that has “the tinge (a little bit) of how white racists talk about African Americans” (Kristof).

The most controversial thing I said was: “We have to be able to criticize bad ideas, and Islam is the Mother lode of bad ideas.” This statement has been met with countless charges of “bigotry” and “racism” online and in the media. But imagine that the year is 1970, and I said: “Communism is the Mother lode of bad ideas.” How reasonable would it be to attack me as a “racist” or as someone who harbors an irrational hatred of Russians, Ukrainians, Chinese, etc. This is precisely the situation I am in. My criticism of Islam is a criticism of beliefs and their consequences—but my fellow liberals reflexively view it as an expression of intolerance toward people.

And the tension on the panel only grew. At one point Affleck sought to cut me off by saying, “Okay, let him [Kristof] talk for a second.” As I finished my sentence, he made a gesture of impatience with his hand, suggesting that I had been droning on for ages. Watching this exchange on television (his body language and tone are less clear online), I find Affleck’s contempt for me fairly amazing.

I want to make one thing clear, however. I did not take Affleck’s hostility personally. This is the kind of thing I now regularly encounter from people who believe the lies about my work that have been sedulously manufactured by Reza Aslan, Glenn Greenwald, Chris Hedges, and many others. If I were seated across the table from someone I “knew” to be a racist and a warmonger, how would I behave? I don’t honestly know.

Kristof made the point that there are brave Muslims who are risking their lives to condemn “extremism” in the Muslim community. Of course there are, and I celebrate these people too. But he seemed completely unaware that he was making my point for me—the point being, of course, that these people are now risking their lives by advocating for basic human rights in the Muslim world.

When I told Affleck that he didn’t understand my argument, he said, “I don’t understand it? You’re argument is ‘You know, black people, we know they shoot each other, they’re blacks!” What did he expect me to say to this—“I stand corrected”?

Although I clearly stated that I wasn’t claiming that all Muslims adhere to the dogmas I was criticizing; distinguished between jihadists, Islamists, conservatives, and the rest of the Muslim community; and explicitly exempted hundreds of millions of Muslims who don’t take the doctrines about blasphemy, apostasy, jihad, and martyrdom seriously, Affleck and Kristof both insisted that I was disparaging all Muslims as a group. Unfortunately, I misspoke slightly at this point, saying that hundreds of millions of Muslims don’t take their “faith” seriously. This led many people to think that I was referring to Muslim atheists (who surely don’t exist in those numbers) and suggesting that the only people who could reform the faith are those who have lost it. I don’t know how many times one must deny that one is referring to an entire group, or cite specific poll results to justify the percentages one is talking about, but no amount of clarification appears sufficient to forestall charges of bigotry and lack of “nuance.”

One of the most depressing things in the aftermath of this exchange is the way Affleck is now being lauded for having exposed my and Maher’s “racism,” “bigotry,” and “hatred of Muslims.” This is yet another sign that simply accusing someone of these sins, however illogically, is sufficient to establish them as facts in the minds of many viewers. It certainly does not help that unscrupulous people like Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald have been spinning the conversation this way.

Of course, Affleck is also being widely reviled as an imbecile. But much of this criticism, too, is unfair. Those who describe him as a mere “actor” who was out of his depth are no better than those who dismiss me as a “neuroscientist” who cannot, therefore, know anything about religion. And Affleck isn’t merely an actor: He’s a director, a producer, a screenwriter, a philanthropist, and may one day be a politician. Even if he were nothing more than an actor, there would be no reason to assume that he’s not smart. In fact, I think he probably is quite smart, and that makes our encounter all the more disheartening.

The important point is that a person’s CV is immaterial as long as he or she is making sense. Unfortunately, Affleck wasn’t—but neither was Kristof, who really is an expert in this area, particularly where the plight of women in the developing world is concerned. His failure to recognize and celebrate the heroism of my friend Ayaan Hirsi Ali remains a journalistic embarrassment and a moral scandal (and I told him so backstage).

After the show, a few things became clear about Affleck’s and Kristof’s views. Rather than trust poll results and the testimony of jihadists and Islamists, they trust the feeling that they get from the dozens of Muslims they have known personally. As a method of gauging Muslim opinion worldwide, this preference is obviously crazy. It is nevertheless understandable. On the basis of their life experiences, they believe that the success of a group like ISIS, despite its ability to recruit people by the thousands from free societies, says nothing about the role that Islamic doctrines play in inspiring global jihad. Rather, they imagine that ISIS is functioning like a bug light for psychopaths—attracting “disaffected young men” who would do terrible things to someone, somewhere, in any case. For some strange reason these disturbed individuals can’t resist an invitation to travel to a foreign desert for the privilege of decapitating journalists and aid workers. I await an entry in the DSM-VI that describes this troubling condition.

Contrary to what many liberals believe, those bad boys who are getting off the bus in Syria at this moment to join ISIS are not all psychopaths, nor are they simply depressed people who have gone to the desert to die. Most of them are profoundly motivated by their beliefs. Many surely feel like spiritual James Bonds, fighting a cosmic war against evil. After all, they are spreading the one true faith to the ends of the earth—or they will die trying, and be martyred, and then spend eternity in Paradise. Secular liberals seem unable to grasp how psychologically rewarding this worldview must be.

As I try to make clear in Waking Up, many positive states of mind, such as ecstasy, are ethically neutral. Which is to say that it really matters what you think the feeling of ecstasy means. If you think it means that the Creator of the Universe is rewarding you for having purged your village of Christians, you are ISIS material. Other bearded young men go to Burning Man, find themselves surrounded by naked women in Day-Glo body paint, and experience a similar state of mind.

After the show, Kristof, Affleck, Maher, and I continued our discussion. At one point, Kristof reiterated the claim that Maher and I had failed to acknowledge the existence of all the good Muslims who condemn ISIS, citing the popular hashtag #NotInOurName. In response, I said: “Yes, I agree that all condemnation of ISIS is good. But what do you think would happen if we had burned a copy of the Koran on tonight’s show? There would be riots in scores of countries. Embassies would fall. In response to our mistreating a book, millions of Muslims would take to the streets, and we would spend the rest of our lives fending off credible threats of murder. But when ISIS crucifies people, buries children alive, and rapes and tortures women by the thousands—all in the name of Islam—the response is a few small demonstrations in Europe and a hashtag.” I don’t think I’m being uncharitable when I say that neither Affleck nor Kristof had an intelligent response to this. Nor did they pretend to doubt the truth of what I said.

I genuinely believe that both Affleck and Kristof mean well. They are very worried about American xenophobia and the prospects of future military adventures. But they are confused about Islam. Like many secular liberals, they refuse to accept the abundant evidence that vast numbers of Muslims believe dangerous things about infidels, apostasy, blasphemy, jihad, and martyrdom. And they do not realize that these doctrines are about as controversial under Islam as the resurrection of Jesus is under Christianity.

However, others in this debate are not so innocent. Our conversation on Real Time was provoked by an interview that Reza Aslan gave on CNN, in which he castigated Maher for the remarks he had made about Islam on the previous show. I have always considered Aslan a comical figure. His thoughts about religion in general are a jumble of pretentious nonsense—yet he speaks with an air of self-importance that would have been embarrassing in Genghis Khan at the height of his power. On the topic of Islam, however, Aslan has begun to seem more sinister. He cannot possibly believe what he says, because nearly everything he says is a lie or a half-truth calibrated to mislead a liberal audience. If he claims something isn’t in the Koran, it probably is. I don’t know what his agenda is, beyond riding a jet stream of white guilt from interview to interview, but he is manipulating liberal biases for the purpose of shutting down conversation on important topics. Given what he surely knows about the contents of the Koran and the hadith, the state of public opinion in the Muslim world, the suffering of women and other disempowered groups, and the real-world effects of deeply held religious beliefs, I find his deception on these issues unconscionable.

As I tried to make clear on Maher’s show, what we need is honest talk about the link between belief and behavior. And no one is suffering the consequences of what Muslim “extremists” believe more than other Muslims are. The civil war between Sunni and Shia, the murder of apostates, the oppression of women—these evils have nothing to do with U.S. bombs or Israeli settlements. Yes, the war in Iraq was a catastrophe—just as Affleck and Kristof suggest. But take a moment to appreciate how bleak it is to admit that the world would be better off if we had left Saddam Hussein in power. Here was one of the most evil men who ever lived, holding an entire country hostage. And yet his tyranny was also preventing a religious war between Shia and Sunni, the massacre of Christians, and other sectarian horrors. To say that we should have left Saddam Hussein alone says some very depressing things about the Muslim world.

Whatever the prospects are for moving Islam out of the Middle Ages, hope lies not with obscurantists like Reza Aslan but with reformers like Maajid Nawaz. The litmus test for intellectual honesty on this point—which so many liberals fail—is to admit that one can draw a straight line from specific doctrines in Islam to the intolerance and violence we see in the Muslim world. Nawaz admits this. I don’t want to give the impression that he and I view Islam exactly the same. In fact, we are now having a written exchange that we will publish as an ebook in the coming months—and I am learning a lot from it. But Nawaz admits that the extent of radicalization in the Muslim community is an enormous problem. Unlike Aslan, he insists that his fellow Muslims must find some way to reinterpret and reform the faith. He believes that Islam has the intellectual resources to do this. I certainly hope he’s right. One thing is clear, however: Muslims must be obliged to do the work of reinterpretation—and for this we need honest conversation.

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9008 followers