Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 9

June 30, 2014

The First Act: Thirds, Fifths, or Sevenths?

Aristotle divided stories into three acts, Elizabethan dramatists preferred five. But exactly how long should the beginning be? Maybe you’ve never worried about how long the first act of your story should be, relative to the rest of your novel. But if you have, read along about my journey and how I settled this question.

Aristotle divided stories into three acts, Elizabethan dramatists preferred five. But exactly how long should the beginning be? Maybe you’ve never worried about how long the first act of your story should be, relative to the rest of your novel. But if you have, read along about my journey and how I settled this question.

Some time ago I dipped into How to Write an Uncommonly Good Novel, edited by Carol Hoover. I went away with notes on the chapter “Proportion in Plot,” contributed by F. M. Maupin. Maupin divides a theoretical 200 page novel into five acts, then discusses around what page number significant plot points tend to fall.

I liked this model and looked at a favorite published novel through its prism. First I had to do some mathematical contortions because, in Maupin’s model, the five acts get divided into four sections of varying lengths. So for now I set aside the five acts in favor of four sections. Below are their functions. (Note: The page numbers go with that 200 page novel; if the novel you are looking at, or writing, is a different length, divide it into five equal acts, then adjust the section pages accordingly.)

-Section 1 (Act I) = pages 1-40, setting up the background of the story

-Section 2 (Act II + first half of Act III) = pages 41-100, showing the developing crisis

-Section 3 (second half of Act III + all of Act IV + first half of Act V) = pages 101-180, leading up to the climax

-Section 4 (second half of Act V) = pages 181-200, wrapping everything up

The novel I studied proved this model. Important events fell exactly where Maupin said they should. But when I sought to apply the model to my own partial draft/outline, I got stuck. However you cut it, into acts or sections, the first part still ends up being ONE-FIFTH of the book. I didn’t think that would work for my story. Sure, I can write forty pages of introductory narrative. But given the amount of material I have for my middle, can I really spare a whole fifth of my limited pages for just introduction? I chewed and chewed on this: What to do?

I continued to write and dip into other books on writing. Eureka! It turns out that, while Maupin’s is an excellent model, it’s not the only one. Other authors vary in their opinions about what makes for the ideal proportion of a first act. Below, the caps are my emphasis.

Here’s the wonderful James Scott Bell about where to position the doorway that leads the reader from the first to the second act: “My rule of thumb is the one-fifth mark, THOUGH IT CAN HAPPEN SOONER.” (Plot and Structure, p. 33) Yippee! Hooray!

Wait, it gets better. David Morrell, in The Successful Novelist, “allows” a first act that’s only ONE SEVENTH long! (On pages 60-61, he proposes three acts or sections. The first and third acts are each one-seventh long, while the second/middle act is five-sevenths.)

And on page 61, Morrell documents Henry James’s The Ambassadors. Morrell sees the structure of this novel as two groups of six acts—which supplies a precedent for first acts that are ONE SIXTH long!

Robert Kernen is also a proponent of shorter first acts. “While the length of act one is, of course, flexible, I recommend keeping it to NO MORE THAN ONE-SIXTH of the entire length of your story. This may seem very brief and out of proportion to the following two acts, but you should compress your story’s opening act so that the audience has all the information it needs but can get quickly into the major thrust of the drama.” (Building Better Plots, p. 19)

My conclusion? We can choose the proportion that best suits our story. To paraphrase the famous phrase, “Don’t worry, keep writing.”

-Sabina I. Rascol

June 24, 2014

How to NOT Edit

To almost all writers, we at Viva Scriva almost always recommend more editing. But there are times when editing will only slow your manuscript down. Most notably during that hallowed first draft, but sometimes further down the road too. When you need to work your way through a motivation or plot problem by free-writing, for example, or when your work has been over-edited and you want to return to a flowing voice. At these times, it becomes hard to turn the editing off, and writers can go to great lengths to stop. Writing longhand or on a typewriter. Writing ‘blind’ by covering up the computer screen. Even e-mailing chapters to themselves then deleting them from physical interference.

Along those lines, a friend recently introduced me to Draft, a writing application that helps with versions and online collaboration. I haven’t tried it yet, but it seems more bare-bones and perhaps easier to jump into than Scrivener, another popular writing software. One of Draft’s benefits is called “Hemingway Mode,” which founder Nate Kontny explains like this:

The best advice about creativity I’ve ever received is: “Write drunk; edit sober” – often attributed to Ernest Hemingway. I don’t take the advice literally. But it points to the fact that writing and editing are two very different functions. One shouldn’t pollute the other. It’s difficult to write if you’re in a editing mindset and removing more words than you’re putting on the page.

So I’ve added Hemingway Mode to help. Draft will turn off your ability to delete anything in your document. You can only write at the end of what you’ve already written. You can’t go back; only forward.

If you’re like me, you have wished that your computer would step in and stop you at times. Maybe Draft is getting ever closer. If only we could get our laptops to start whispering motivations when we stop typing…

June 20, 2014

NEVER Give Up on a Book You Believe In

[image error]When I was pregnant with my second child, who is now 10 years old, I started writing a picture book called Squeaks, Stumps, and Surprises: A Big Brother’s Guide to Life with a New Baby. I was trying to see my second pregnancy and the appearance of a new baby in the family through my first child’s eyes. I asked him and his friends what they thought about pregnancy and new babies, especially new siblings. And I learned that little kids don’t see things the way we adults do.

In the book, I tried to capture the voice of a slightly older, wiser kid giving insider advice about what life with a new baby would really be like. I loved writing it, I loved revising it, and when I submitted it to publishers, I got nice notes back about the writing and the concept. But all agreed it wouldn’t stand out in the crowded New Baby market.

So I went back to it, revising it again, making the voice stronger, fresher, funnier. This went on for several years (I had a new baby at home after all) before I submitted again. This time I found a few editors who liked it, too. It went to acquisitions several times, but alas, no one bought it.

I got busy with other projects, busy with my two kids, and forgot about the manuscript for a while, perhaps years. If I happened to think of it, I would open the most recent version and read it. I’d think: “I still really like this book.” Sometimes I’d play around with it again. I changed the boy to a girl. I broke the book into sections. I added more dialogue, more funny lists, more punch lines. I cut it radically. I added more material. I cut again. I went from one narrator to two: a boy and a girl.

I started working with a wonderful agent who sold some of my manuscripts. When I first showed her this one, she said something to the effect of: “I’m not sure this would stand out in the crowded New Baby market.” Sound familiar? So I put it away again.

In the meantime, I started writing a graphic novel. (MUDDY MAX, coming this August!) Sometime while working on the graphic novel, I took yet another peek at the new baby book. I thought: “I still really like this book.” And I had an idea. What if the book was a picture book/graphic novel hybrid with some main narrative text and some funny scenes in comic form? I carved out some time to try this, got great feedback from my critique groups, revised again and showed my agent. This time she said: “All right, let’s give it a try.”

And I am happy, ecstatic, thrilled to report, that TEN YEARS after first writing the book, we got an offer on it. I am still in shock that it actually happened. Look for The Big Kids’ Guide to Life with a New Baby sometime in 2016!

And don’t EVER give up on a book project you believe in.

Elizabeth Rusch

P.S. In case it’s not obvious from the story above, it is OK to put a manuscript aside for a while (months or even years), play around with it a lot, try some radical revisions, get feedback, put it away again, revisit it again. But if you like it, if you believe in it, if there is something in there you think is special, don’t give up, don’t ever give up.

June 12, 2014

On Rejection

It happens. All the time. Even once you start selling books, you still get rejected. A lot. Yup. When it happens to me, I tell the Scrivas. They commiserate, and I move on to the next thing. That’s it.

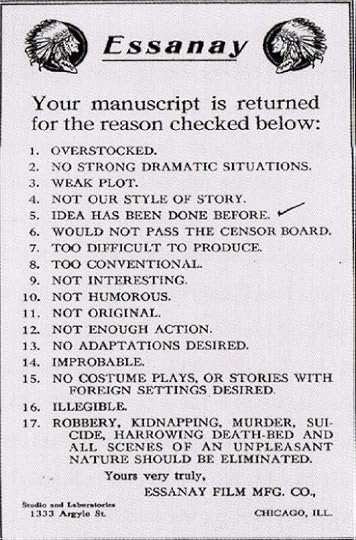

So in honor of rejection and the people I share it with, I offer you this hilarious form rejection letter from the 1920s. Perhaps for fun you could fill this out for your current WIP and get the rejections over with in advance. Or maybe we should all write a condolence note to George R.R. Martin. He’s never getting past #17.

June 4, 2014

Crafting Characters? Take Your Scarecrow to Lunch

A while back, the Scrivas had a weekend retreat at a farm in Hood River. Outside the living room window “stood” this scarecrow, a stark reminder to me that the main characters in novels have to be more than the literary equivalent of a headless sack of straw and old clothes. Characters like that are for the birds. Readers deserve fully formed people, whether sympathetic or scary, if you want them to flock to your story.

A while back, the Scrivas had a weekend retreat at a farm in Hood River. Outside the living room window “stood” this scarecrow, a stark reminder to me that the main characters in novels have to be more than the literary equivalent of a headless sack of straw and old clothes. Characters like that are for the birds. Readers deserve fully formed people, whether sympathetic or scary, if you want them to flock to your story.

There are lots of ways to create strong characters. This flowchart has made the rounds about how to craft strong, memorable female characters. I admit that I’m not as thorough. Still, I try to get to know my main characters before I introduce them to their readers. I can’t hope to make them strong until I know them well enough and craft them fully enough so that they don’t fall apart in the editing process. Here’s what works for me.

I craft a complete physical description, including an image or two from a magazine, Google, or a photo service such as Getty’s iStock.

I include flaws, talents, habits, or other traits, which can get the reader’s attention and serve as a way to identify that character to others in the story. Does he or she collect bubble gum wrappers, count to 18 before crossing the street, bake pineapple upside cakes during hurricanes, or, and in my work-in-progress suffer from magical thinking about a dead parent? We all have quirks; we all are wounded in some way.

I give the character a clear and forthright voice (at least for this one time) so that he or she can join me for a day and comment on everything I do (well, almost everything). “Why spend your time knitting socks when you could be river rafting?” “I’d never walk this slow.” “Don’t you ever eat cheeseburgers?” “Wow, so this is the library you go to. I’ve never seen anything so elegant!” You get the picture. I set the chatterbox to full throttle and listen, listen, listen.

Once I’ve followed my character-creating routine, my character might look more like this scarecrow found in a field in Japan. Now he or she is ready to meet THE CHALLENGES, whatever it is that the character has to overcome in order to, well, become an even stronger character, just like in real life.

Once I’ve followed my character-creating routine, my character might look more like this scarecrow found in a field in Japan. Now he or she is ready to meet THE CHALLENGES, whatever it is that the character has to overcome in order to, well, become an even stronger character, just like in real life.

Here’s where things get tricky. Next up, a Scriva critique. I might find something vital that I missed in developing that character. Or I might realize that the character … although not my main one … yet… doesn’t have what it takes to move the plot along in any meaningful manner. Then it’s good-bye. No matter how colorful or quirky, my character gets voted off Work-In-Progress Island.

Scarecrows and stories have been around since forever minus epsilon. So have stories about scarecrows, including one about Kuebiko dating back to the eighth century, but that’s for another post.

May 31, 2014

Conversations with Oneself

What do you know? I was using a writerly tool beloved by some top writers without knowing I was part of a tradition. You yourself may be using this tool too. Or you can consider adopting it, if it suits your style.

What do you know? I was using a writerly tool beloved by some top writers without knowing I was part of a tradition. You yourself may be using this tool too. Or you can consider adopting it, if it suits your style.

When discussing outlining in his excellent book, Plot & Structure, James Scott Bell notes an alternative to the traditional outline. He got the idea from David Morrell’s The Successful Novelist: A Lifetime of Lessons about Writing and Publishing. Morrell, in his turn, got the idea from an interview with Harold Robbins, who got it from… OK, that I don’t know.

What is the tool? Conversations with oneself. Written conversations.

Per Bell in Plot & Structure (p. 154; see also pp. 165-66), this is what David Morrell does.

“He likes to start a free-form letter to himself as the subject takes shape in his mind. He’ll add to it daily, letting the thing grow in whatever direction his mind takes him. What this method does is mine rich ore in the subconscious and imagination, yielding deeper story structure.”

In The Successful Novelist’s “Lesson 2, Getting Focused,” Morrell describes how most writers get started on their story. They talk with friends, their subconscious working as the story gains focus. Then they put these ideas in a dull outline. Then maybe they lose interest—or forget what got them excited about the story in the first place.

“What’s to be done?” Morrell asks on page 17. “For starters, let’s identify the inadequacies of the process I just described. One limitation would be that a plot outline puts too much emphasis on the surface of events and not enough on their thematic and emotional significance. As a consequence, the book that results from the outline sometimes feels thin and mechanical. Another limitation would be that an outline doesn’t provide a step-by-step record of the psychological process that you went through to work out the story. It only documents the final result. As a consequence, if you become too familiar with the story and lose interest in it, you have difficulty re-creating the initial enthusiasm. Still a further problem relates to those conversations you had with your friends or your significant other. Hemingway insisted that a writer shouldn’t talk about a story before it was written. He felt that too many good ideas ended in the air rather than on the page and, worse, that the emotional release of talking about a story took away the pressure of needing to write it. – Writing. That’s the point. While all this thinking and talking has been going on, not a lot of writing has been accomplished. But a writer, like a concert pianist, has to keep in daily practice.”

Though I, in the last couple of years, have started having occasional, judicious conversations about my novels with the Scrivas, all along, my main place to consider story ideas is a document I titled “Thoughts While Writing.” Every time I sit down to write, besides the appropriate story chapter, I open too “Thoughts While Writing.” I use this multi-part document (I start a new file when one gets too long) in many ways.

I prime myself by jotting down what I did before sitting down to write, or what I’ll do when I finish. I record plot developments to remember for later parts of the story line. I try bits of dialogue. I pray—for wisdom, inspiration, persistence. I debate the merits of new ideas, finding holes I need to plug in and stumbling across wonderful connections. I color-code the main threads I’m weaving through my novel. Everything that goes on in my mind related to my story gets written down as it comes. It’s not lost. It’s stored, ready, available. With apologies to J. K. Rowling, it’s like my own personal Pensieve.

Of course, these written conversations don’t require a computer. They can take place just as well in a notebook. Some writers have a general writing notebook storing all idea nuggets that work their way up from their subconscious, ideas for all current and possible stories. It seems to me, though, that for full benefits of Morrell’s idea, one notebook should be dedicated to the conversations a writer is having with himself about one particular book.

So try it. Take it from me—or from James Scott Bell, David Morrell, Harold Robbins… Hold some conversations with yourself. Write them down. They’ll be useful in many ways later.

-Sabina I. Rascol

May 24, 2014

Editing…Without Touching a Word

When writers meet up, one of the first questions parried is, “How’s the writing going?” Recently I had this conversation with another Scriva. Both of us have been overwhelmed with non-writing life, and said (rather dejectedly and a little shamefully), “I haven’t been writing.” And then we proceeded to talk about the new developments in the books we “haven’t been writing” for an hour or two. She was reading Writing the Breakout Novel and trying to decide which of her six plot elements was most important. (What story do I have to tell?) She was also thinking about combining characters and waking up earlier to steal some writing time. I have been ruminating on something an agent told me months ago. And though I haven’t sat down with my laptop for months, my main character keeps visiting me at odd times and explaining more of his backstory (I actually hear his voice in my head.) I’m getting more clarity on my main theme, all without touching a word.

When writers meet up, one of the first questions parried is, “How’s the writing going?” Recently I had this conversation with another Scriva. Both of us have been overwhelmed with non-writing life, and said (rather dejectedly and a little shamefully), “I haven’t been writing.” And then we proceeded to talk about the new developments in the books we “haven’t been writing” for an hour or two. She was reading Writing the Breakout Novel and trying to decide which of her six plot elements was most important. (What story do I have to tell?) She was also thinking about combining characters and waking up earlier to steal some writing time. I have been ruminating on something an agent told me months ago. And though I haven’t sat down with my laptop for months, my main character keeps visiting me at odd times and explaining more of his backstory (I actually hear his voice in my head.) I’m getting more clarity on my main theme, all without touching a word.

It only really struck me the next day: We are still editing! I have missed my story in the months I have been away from it. That is a healthy thing. Not healthy is the feeling that I have betrayed myself by letting it languish. Less healthy still: the despair that I’ll never get back to my book, and it will never, ever be published. But stories are not quite the same as children or pets. They can be ignored and not perish. They can be argued with and not suffer. They can be put in a drawer and … Well, you get the point. Our characters can be trusted to rise again. If you are mourning your own writing, or just not sure where to go next, here are some non-traditional editing ideas.

Read an inspiring writing book that really gets your blood going.

Re-read authors in your genre who blow your mind.

Try to dream about your characters.

Imagine your characters interacting with the real world (like when you’re at the grocery store).

Talk about your book with your friends.

Talk to your characters, in your head or in your journal.

Watch movies that reflect the setting in your book.

Make a soundtrack for your main character’s life.

May 20, 2014

A Tense Surprise

In an earlier post about how I sometimes do multiple simultaneous drafts of the same manuscript, I mentioned how a critiquer had suggested trying to rewrite my picture book biography of piano inventor Bartolomeo Cristofori in present tense. PRESENT TENSE? A biography from 1700s, late Renaissance Italy, in PRESENT TENSE? Sounds crazy. I balked, as did the rest of my fellow critiquers.

In an earlier post about how I sometimes do multiple simultaneous drafts of the same manuscript, I mentioned how a critiquer had suggested trying to rewrite my picture book biography of piano inventor Bartolomeo Cristofori in present tense. PRESENT TENSE? A biography from 1700s, late Renaissance Italy, in PRESENT TENSE? Sounds crazy. I balked, as did the rest of my fellow critiquers.

But I have a little rule for myself to at least give most suggestions, even the ones I don’t agree with, a try. Especially if its something I can do easily or test out with a small section. So I did it. I rewrote the whole thing in present tense.

I didn’t really look at the manuscript again until reading the two versions aloud at a critique group meeting. Wonder of wonder, miracle of miracles, the present tense version of the story came to life. It jumped off the page. It sang. I knew it as I read it and the comments were unanimous: “I didn’t think the present tense would work, but I love it.”

So there you have it. Two lessons for me from this experience: Even if you don’t agree with a suggestion, consider giving it a try. And play around it tense. You never what how it could transform your manuscript.

Elizabeth Rusch

May 15, 2014

The Power of Words– A Little Writerly Pick-Me-Up

This short YouTube video really spoke to me about the power we writers have with our words. If any of you are feeling down or stuck or like your work and words don’t matter, this will help pick you up.

Remember, “Change your words. Change your world.”

We writers make a difference! Our work MATTERS!

Happy Writing!

-Nicole Marie Schreiber

May 12, 2014

What is YA anyhow? Smart stuff from editor Cheryl Klein

My dear friend and kick-ass writer, Cidney Swanson, gave me a copy of Cheryl Klein‘s book SECOND SIGHT: AN EDITOR’S TALKS ON WRITING, REVISING & PUBLISHING BOOKS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS. It is so awesome.

My dear friend and kick-ass writer, Cidney Swanson, gave me a copy of Cheryl Klein‘s book SECOND SIGHT: AN EDITOR’S TALKS ON WRITING, REVISING & PUBLISHING BOOKS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS. It is so awesome.

My favorite parts, which you should definitely read ASAP, are the sections when she shows multiple drafts of the same manuscript chapter through multiple rounds of revision. This will help you learn to revise more than anything I can think of. Go buy the book now!

But what I wanted to call out in this post is the chapter entitled “Theory: A Definition of Young Adult Literature.” Since many of us Scrivas (Nicole, Mary, Ruth, Melissa, Addie, and me) write YA fiction, I spend a lot of time thinking about what makes a good YA novel. Cheryl Klein’s exploration of the form is spot on brilliant.

She says:

So I’ve been thinking off and on about a practical definition of YA literature — something I could look at to help me decide whether a manuscript is an adult novel or a middle-grade novel or, indeed, a YA. Such delineations don’t matter to me as a reader — a good book is a good book — but they do matter to me as an editor and publisher, because I want every book I publish to find the audience that is right for it, and sometimes, despite a child or teenage protagonist, a manuscript is meant for an adult audience. Hence I have written the definition below to help me think through these situations as they come up. This is very much a WORKING theory; I hope you all will offer challenges, counterexamples, additions or arguments to help me improve what I’m saying here. But here’s what I have right now — the definition broken into five parts for easier parsing:

A YA novel is centrally interested in the experience and growth of

its teenage protagonist(s),

whose dramatized choices, actions, and concerns drive the

story,

and it is narrated with relative immediacy to that teenage perspective.

CONTINUED HERE…

In the complete post, which you really must read, she deconstructs each of these points and adds a sixth implicit feature of YA. I really thought Cheryl’s thoughts were wonderful. Enjoy!