Exponent II's Blog, page 63

May 15, 2024

My Least Favorite Elder Oaks Quote Ever (And Why Women Getting Educated Was Never Controversial – Only Getting Paid For It Was)

I wrote a post last week about a church video from the 90s that told me it was sinful to seek a career because I was a girl:

Don’t Gaslight Me – I Know What I Was Taught in Young Women’s in the 90s ^ Exponent II Blog

A number of responses admitted that while sure, the video itself was horrendous, not every girl growing up received that message. For example, some men explained that their sisters’ education was equally valued in their homes, and many women expressed gratitude for leaders and parents who had encouraged them to attend college.

They are not wrong, and I absolutely agree that I was encouraged to seek higher education. Going to college was never a question for my sister or myself, and three months after graduating from high school I was dropped off at my BYU dorm. No one ever discouraged me from becoming educated.

Rather, they discouraged me from turning my education into anything more than motherhood. Education was good, but getting a paycheck was bad. I was supposed to get educated, find a husband, and be financially dependent on him for the rest of my life. My education was exclusively to make me a better mother, not to give me skills to provide for myself.

Because of this, I knew long before I met or married anyone that my future husband’s education would take priority over mine. If we ever had to choose, he would get a degree and I wouldn’t. If only one of us could get a graduate degree, it would be him. If we were both working and he needed to relocate for a work opportunity, I would quit my job and follow him. And once we had children, it was without question that I would be the one to stop working while he continued building his career.

Getting an education as a woman was never controversial, but using that education to build a financially independent lifestyle was.

Our soon-to-be prophet Dallin H. Oaks is a complicated man on the topic of working women. His own father passed away and he was raised by a single, working mother. He was among the first to comment recently on Relief Society president Camille Johnson’s social media page, praising her for speaking about her career. His current wife Kristen was a single working woman until she married him at age 53. And yet, in a 2013 interview Elder Oaks said this about women and careers (at about the 29:13 mark of the video I’ll link below):

“I think that as young women have been encouraged – properly, in my view, to get an education and make plans to support themselves, that many young men have seen the accomplishments of the women in such a way as to be frightened of them. And I think that a woman who has prepared herself properly needs to be careful that she can communicate to a young man the fact that she’s willing to put that career aside, to be a Latter-day Saint wife and mother, and she can take it up later… I’ve had many young men say, “I don’t think young women today are interested in being married. I can’t find anybody because they’re all committed to their careers, and that does stand in the way of marriage, and it frightens off shy young men, for whom we should feel so sorry .”

Kristen Oaks also said (at about the 28:45 mark of the same video), “This is for young women right now, coming out of college…I think that women now are really worried about careers, and they feel they have to develop themselves, and I would just say to them, “Don’t get lost in that”. Because it’s awfully lonely when you’re 50, and all you have is your career – because I’ve done that.”

Mormon Channel Interview with the Oaks’

The message to girls and women has never been, “Don’t get an education”. Rather, it’s been, “Sure, get an education – but only to become a better future mother”.

May 14, 2024

“Paste-up” Parties and the Early Production of Exponent II

“I would be happy to talk to you,” she said, “but I don’t do Zoom. You are welcome to come to my condo.”

Fair enough, I thought, for a ninety-year-old woman and Founding Mother of Exponent II. So, in October 2022, Heather Sundahl and I happily made the trip to Grethe Peterson’s condo near the base of Emigration Canyon, overlooking Salt Lake City. Grethe graciously told us about her life and her family’s years in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and gave us a copy of her hot-off-the-press self-published memoir, Growing Into Myself.

With Grethe’s death last month, I’m thinking about the years that the Petersons opened their home to Exponent II’s production.

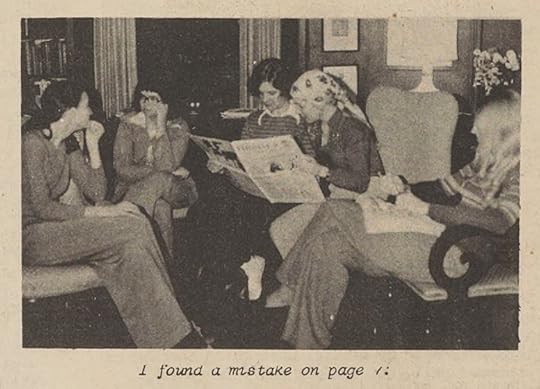

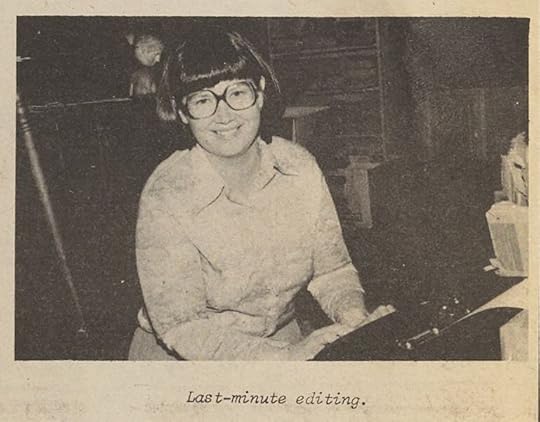

Before the digital age, Exponent II was a hand-produced, “kitchen table”-style newspaper. The staff put it all together in quarterly “paste-up” parties that often lasted several evenings. The typewritten copy was literally in pieces—a paragraph here, a single retyped line there. It all had to be meticulously assembled and proofread before being sent for printing.

The first paste-up party was held at Maryann MacMurray’s home in the Boston suburbs in June 1974. Over the years, paste-up and mailing parties changed locations as volunteers moved and life’s demands undulated. Carrel and Garret Sheldon opened their home to the paper’s production many times in its early decades, but between much of 1976 and 1978, Exponent II was produced in the Cambridge home of Grethe and Chase Peterson.

The Petersons lived at 95 Irving Street in the large historic home that prominent American psychologist and philosopher William James built for his wife in 1887. The home provided space for discussion groups in the living room, board meetings in the library, and mailings of the paper prepared on the dining room table. They held quarterly paste-up meetings in the fourth-story, uninsulated attic space, utilizing a large ping-pong table as the central workstation.

In her memoir, Peterson recalls, “We kept the lines straight with the help of graph paper taped to a light board (thanks to Carrel’s husband, Garret, an engineer) so the blue lines wouldn’t show up in the finished product but would help us line everything up. The ping pong table was soon littered with lamps, graph paper, scotch tape, scissors, and glue.” The staff tacked previous issues of the paper up on the walls as a visible template for design continuity. As deadlines approached, Exponent women came and went freely, with the Peterson’s golden retriever, Muffin, taking on the role of eager receptionist.

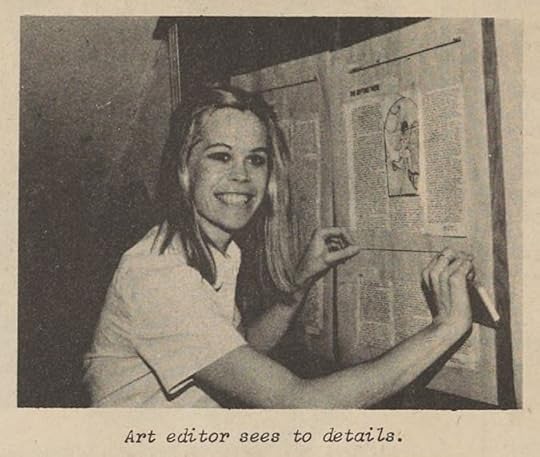

Perhaps understanding the historical nature of their undertaking, the staff documented their work process in the Winter 1978 issue. From the articles “95 Irving Street,” “From Our House to Yours,” and the photographic essay “Putting it all Together,” we find rich details and the best collection of images of the paper’s production that we have.

Grethe was a matriarch of Mormon Feminism. Beginning in 1970, she participated in the Boston Mormon feminists’ consciousness-raising meetings and contributed to the “Pink Issue” of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. When Claudia Bushman resigned as editor at the end of 1975 due to pressure from LDS general authorities, Grethe joined the paper’s editorial team and later became its managing editor alongside the paper’s second editor-in-chief, Nancy Dredge.

More about her fascinating life, including her role in founding the Children’s Justice Center in Utah, can be found in her obituary here, along with the details of her upcoming memorial service. While I have loved many things about the process of co-writing the forthcoming book, Fifty Years of Exponent II (Signature Books, 2024), the most transformative has been meeting and learning about the lives of the women who founded this paper or carried on its important work.

May 10, 2024

Our Bloggers Recommend: Why leaders’ efforts to keep women in the faith could backfire – and what could work

Blogger Caroline Kline was interviewed on Mormon Land Podcast this week! Discussing President Camille Johnson’s recent message at BYU Women’s Conference, Caroline said, “I have mixed feelings. Side by side with my happiness about this openness in terms of her speaking about her career, there’s also a little bit of frustration at what was left unsaid. Her decision to pursue a career and motherhood simultaneously in the 80s and 90s went against very clear counsel from the highest leaders of our church that told women to forgo paid employment. This was very clear rhetoric, outlining the dangers and misguided nature of mothers working, and the fact that women’s divine role was to be a mother in the home and not in the workforce. This rhetoric was powerful and pervasive, and it influenced a generation or two of women to either forgo their career dreams or feel a certain amount of guilt doing so, even if they had to do it for financial necessity.”

Listen to the entire interview at the link below and subscribe for free to the Mormon Land podcast.

Guest Post: The Insidious Exchange of Community for Covenants

By Candice Wendt

My ward and stake keep hammering down on my 12-year-old son that boys serving missions is a mandate from God. But he’s not buying it. There are all kinds of problematic things going on I could unpack here, but for the moment, I’ll focus on just one obstacle. As we have attended our ward, which has eight proselyting missionaries assigned to it, my son has gotten the impression that missionaries’ efforts to build community are basically fruitless. He witnesses that church is a revolving door with people entering and exiting as they realize we’re not as communitarian as we seemed.

We attend church in the heart of Montreal. Our mission is one of the highest baptizing missions in the world, partly because our city welcomes a large portion of Canada’s refugees and immigrants. For many who are baptized, missionaries offer social respite. At testimony meetings, converts often thank missionaries for being their friends. But life as a member offers relatively little social time or enjoyment. Being in the ward is mostly about passive listening and being told to follow leaders and go to the temple. Social events are few, and often bomb, like when our ward Christmas party dinner was two hours late and all the food ran out before 50 people had eaten anything. You’re more likely to get asked to clean our very dirty building than be asked to dinner. Most converts stop coming after a few weeks or months.

LDS church community hasn’t always been this way. I remember the strong spirit of togetherness at homemaking meetings during my childhood in the western US. I recall the sound of sewing machines, the smell of bread baking, and the pleasure of watching women laughing together. I ran around the building during those gatherings, and later gained my first experiences babysitting so young moms could attend. I remember Halloween parties that were genuinely fun for all ages. At one, my bishopric performed a comedy skit that involved them wearing tutus. Wards worked like caring extended families. Some of this is childhood nostalgia, but some of it is cold hard reality. Community life is breaking down all over the world, and the church has been going along with this tide instead of resisting it.

The institutional church has long been taking an insidious turn away from community and toward covenants as its highest value. General leaders have cut ward budgets and removed, downsized, and deemphasized the programming that once fostered friendships, celebrated accomplishments, and created social fun.

Once as a teen, I displayed an appliqué quilt I made and a history of my great grandfather I transcribed at my ward’s new beginnings meeting. Other girls also shared. We felt admired and loved by the community. My daughter has no such opportunities for recognition.

When I got married and was required to leave my BYU singles’ ward, I was suddenly cut off from friends I loved and from fun social ward routines. I felt betrayed as I realized it seemed the church had made the singles’ ward so socially rewarding to get me married in the temple, then dumped me into an isolated life once their objective was fulfilled. The sudden loss of support contributed to my mental health plummeting as I had a baby and completed a master’s degree over the next two years.

Leaders are treating temple covenants as the sole thing we need to access faith and happiness. Some older members are on board with this. Maybe this is because older people are biased (including general authorities); they no longer have pressing developmental and social needs themselves, and their thoughts are turned toward death and comforting hopes of an afterlife.

One huge problem with the exchange of covenants for community is that temples do not tend to needs for connection. The temple is not better for me than scrolling on a cell phone in the sense that both are downloads of information while I’m essentially in isolation. The temple is not a place to talk or connect. In the celestial room, we may whisper awkwardly or feel we’re on display under bright lights. The ordinances have only become more devoid of interaction over time.

Covenants becoming the heart of religious life alienates members who have concerns about the temple. Some members hold the things Joseph Smith brought about toward the end of his life in suspicion due to his abusive, emotionally numb and compulsive behaviors during that period of time (i.e.. the nightmarish details of polygamy). There are many other fraught questions surrounding the temple, such as the ethics of worthiness interviews and entrance requirements. Many younger members are not confident ordinances should be at the center of living the gospel, or whether God actually needs them. For some, the focus on helping the dead feels irrelevant and misdirected when there are so many living people who need love and attention.

Social disconnection plus hope of a future life with God is not an equation for happiness. We need pleasurable community experiences to rejoice in the gospel and enact its meanings fully. Enjoyment is a blend of relationships, memories, and pleasure (e.g. eating, recreating, having fun; see this interview with Arthur Brooks about happiness from the Ten Percent Happier Podcast). Such experiences are a vital element of long-term happiness.To be happy in our church life, we need to eat with and play with people, make friends, and create memories together.

At a lecture at McGill University last October, philosopher Mark Wrathall discussed how from a phenomenological perspective, faith is not belief (such as in theology, afterlife structures, etc.), but loving and compassionate relations and community building. Faith itself works in a non-cognitive way, it is expressed and grown through community practices. I came away from this lecture with a strong recognition that what matters most to me about about my religious life is how it helps me live a better life now, not how it makes me think or feel differently about the possibility of an afterlife, something which is inaccessible, mysterious, and in many ways completely irrelevant to me now.

Jesus lived a community and relationship-centered life. He spent most of his time conversing, eating with people, connecting with groups, and initiating and nurturing friendships. Disagreement and stretching the limits of his friends’ thinking about themselves and their relationships was his continual mode and venture. Deep levels of emotional closeness seem to have been important to him. He did not live a temple-centered life; he lived a love and humanity-centered life. Following Jesus means subversively fostering community, friendship and love, even when the church itself has ceased to value these things.

I recently told my son after an uncomfortable discussion in Young Men’s that he’ll never receive pressure or guilt from me. I told him I know he is going to be a wonderful person whether he chooses to serve a mission or not, whether he marries in the temple or not, and whether he develops any kind of faith or not. He hugged me and said, “I’m so happy we can talk about these things.” The covenant-obsessed version of the church is not proving loving, relational or supportive enough for my caring children or their exceptional peers. They deserve so much better. Like so many millennial moms around me, you can plan on me resisting the tide and putting love and connection first.

Candice Wendt is a staff member of McGill University’s Office of Religious and Spiritual Life and a contributing editor at Wayfare. She is married to the psychology scholar Dennis Wendt and they are raising two strong-willed, artistic, French-speaking teens together.

May 9, 2024

A Failed Mother’s Day Post

I’ve been having difficulty writing a blog post for Mother’s Day. My notebook is filled with stories about my mom, notes about the origin of the word mother, and experiences from my motherhood. But they just sit there with a debilitating heaviness, with an inadequacy that I can’t shake and I’m beginning to think that maybe it’s because I grew up in the fog of patriarchy where ONE Sunday a year is given to mothers; one day a year that isn’t exclusively about fathers, sons, hes, and hims. One day when Mother is said out loud, her stories told, and her body celebrated for the life she brings. That’s a lot of internalized pressure and I don’t want to blow it.

I haven’t been to church in months but am still forced to grapple with the patriarchal muscle I’ve been exercising for the past 37 years and the weak, atrophied matrifocal muscle I’ve neglected for almost as long. I can’t seem to escape the patriarchal illusion that motherhood is limited and therefore needs to be protected, exalted, or memorialized in one great day or in one great way. But mothers are human and common and sometimes wonderful and sometimes terrible and always, every time, at the origin of life. That’s their magic that is forgotten in the commodification of motherhood in patriarchal systems.

I love the imagery of the Father God as the sun, the Mother God as the Earth, and their human children as trees that need sunlight and soil to grow. This balanced metaphor is beautiful . . . however, this was not my experience growing up as a woman in the LDS church where being a child of God is less like a tree and more like a bouquet: a bunch of blossoms cut from their roots and placed in a crystal vase. Bouquets are meant to be oohed and aahed over until they wilt and die without soil. They’re meant to look vibrant and beautiful but are unsustainable without their roots and the earth that holds them.

As a human, my roots are from my mother. Everyone’s roots start within their mother. I forgot how beautifully common that is. My mom is not a commodity or a more important woman to be memorialized on Mother’s Day, she’s an aging human who did this miraculous thing for me by bringing me into this world with her body. She lives and breathes like every other person on this planet. She is a billion stories. And in my desperation to honor her on her one day, I forgot all that. I forgot my roots because all I ever see or hear about is the sun.

Patriarchy gives fathers and sons every Sunday. And allows them to live and choose and fail and flounder and teach and thrive in a million stories. Consequently, mothers and daughters traditionally have one day for their stories and therefore are reduced to just the few best ones. (Hence, my hypothesis for my inability to write a meaningful Mother’s Day post.) But when I step away from patriarchy, the language and stories of mothers are common and vital. Always.

Anyway, Mary Oliver’s poem, “The Journey,” makes me think of my mom and how she fights her demons and always wins; my mom is a full-blown human on a journey to find herself. I dedicate this poem to her and to all the mothers who untangle themselves from the voices, expectations, and clawing hands of patriarchy; mothers who often forget their power, only to be awed by it (and awe everyone around them) again and again. I love you.

The JourneyBy Mary Oliver

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice–

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But you didn’t stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations–

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voices behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice,

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do–

determined to save

the only life you could save.

Photo by Zoe Schaeffer on Unsplash

May 7, 2024

Don’t Gaslight Me – I Know What I Was Taught in Young Women’s in the 90s

A recent address by general Relief Society president Camille Johnson has caused some stir online. (Read this excellent post on the topic by fellow Exponent blogger Caroline.) President Johnson chose to pursue a law career in direct opposition to the prophetic counsel of her day to stay at home with her children. Many women (including myself) were frustrated by the current praise from church leadership for her life path, including a comment on her social media from President Dallin H. Oaks himself. Was pursuing a financially unnecessary career solely for personal fulfillment in addition to motherhood really an option? It never felt like an option to me!

In the online discussion that followed, I was surprised to see many active LDS women coming to defend the church and rewrite history. I read a comment from someone I knew personally in the 1990s stating that she’d never heard a prophet say women needed to stay at home. (In response to which I exclaimed, “What?!” so loudly at my phone screen that I startled the cat on my lap.) This woman is my age and went through the exact same young women’s program as me, and she and I even discussed the need to be stay-at-home moms when we were still teenagers. The idea that she could now claim these things had never been taught astounded me. Does she genuinely not remember?

I’m a product of the LDS Young Women’s program of the 1990s. I became a Beehive in my Utah ward in June of 1993 and graduated from high school in May of 1999. If there’s one thing I can personally claim expertise on, it’s what women and girls in my generation were told we should do with their lives. It was extraordinarily clear. We were supposed to get married as soon as possible after high school, have lots of babies, and stay at home with those children. Planning for a career or choosing to work outside of the home for any reason other than a complete emergency would be Satan’s plan for my life, not God’s.

There’s an old church film from 1991 called “For This Child I Have Prayed”, that I just watched for the first time in a quarter of a century. I was shown this film many times in my Young Women’s classes in the 90s, but I’d forgotten about it since graduating high school. If you have twelve minutes to spare, you can check out the full video here on the church’s website:

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/media/video/2011-03-0061-for-this-child-i-prayed?lang=eng

If you don’t have enough time or interest to watch it, I’ll give a recap! A very bright young woman in a lab coat is congratulated by a female teacher who puts her arm lovingly around her and says, “Kelly, I want to congratulate you on your excellent test scores! They were some of the highest I’ve seen in my thirty years of teaching.” The teacher asks if she’s heard back on any scholarships, compliments her “tremendous mind” and expresses hope that she will make “immense contributions” to her field of research. Kelly uncomfortably responds by saying, “But I want to have a family”, to which her teacher kindly reassures her that it’s possible to do both, explaining that most corporations have plans that allow maternity leave for mothers to care for their babies. She again praises Kelly’s mind and encourages her to think about all of the people she can influence in the world, not just her own children. Kelly looks torn and concerned.

In this story, the female teacher encouraging her to succeed represents Satan’s plan for her life.

In this story, the female teacher encouraging her to succeed represents Satan’s plan for her life.(I would like to briefly pause this recap to point out that no male teacher has ever said these words to a future father. Men don’t wrestle with the choice of whether to have a career or a family. I wish more LDS men would realize the domestic burden that LDS women have collectively taken on to provide them with the freedom and flexibility to achieve their dreams, build their resumes, and maintain financial independence for life. This is an exclusively female dilemma.)

Next in the story, Kelly reads her patriarchal blessing. It tells her she’s been blessed with many talents – which she is supposed to use in her home to teach her children.

Kelly’s patriarchal blessing was very unique and special! It told her to do exactly the same thing as every other girl.

Kelly’s patriarchal blessing was very unique and special! It told her to do exactly the same thing as every other girl.Later in her school’s media center, Kelly’s best friend bounces up excitedly to announce she was accepted into the university of her choice. The friend makes Kelly promise to come visit her at school, then rattles off a list of things she wants to do with her life. First off, she wants to own a sports car. (As do all unfaithful women, I’m sure.) Then she says, “There are so many doors out there open for me!” Kelly mentions to this friend the children she’ll have someday, and the friend immediately jumps up and backs away from her uncomfortably, saying, “Whoa, no kids for me for awhile! When I meet the right guy and we build up some security, maybe. I’ve got plenty of time before I start thinking about a family.” Kelly looks lost in her thoughts, contemplating her friend’s plans.

Kelly’s best friend is excited to follow Satan’s plan to purchase a sports car before getting pregnant.

Kelly’s best friend is excited to follow Satan’s plan to purchase a sports car before getting pregnant.At home, Kelly goes to the attic where she finds a box of her mom’s belongings. She puts on her mom’s wedding veil and thumbs through her mom’s childhood scriptures where a primary leader had written, “For perfect attendance in primary. May you grow to be a righteous mother in Zion”. Kelly smiles. That lady knew what’s up.

Quick sidenote: the veil Kelly is wearing doesn’t seem to match the veil in the wedding photo of her mom with her dad. Was her mom secretly married before? Are we about to learn a family secret?! I’m suddenly very engaged in this story. Tell me more!

Quick sidenote: the veil Kelly is wearing doesn’t seem to match the veil in the wedding photo of her mom with her dad. Was her mom secretly married before? Are we about to learn a family secret?! I’m suddenly very engaged in this story. Tell me more!Kelly goes on to uncover even more secrets from her mother’s past, including a certificate for highest academic achievement and that she was voted “Girl Most Likely To Succeed”. It’s becoming apparent now where Kelly got her intelligence from, and it wasn’t her father (if he’s even her real father). A melodramatic song plays as Kelly looks at her mom’s achievements from her youth, and the lyrics are:

“My mother loves unselfishly, helps others in their need. She loves the teachings of her Lord and teaches them to me. Of all the things that she could choose (like a sports car!), she chose the will of God, To love and lead us back to Him.”

Kelly’s mom arrives in the attic, and Kelly teases her about her old hairstyles, clearly unaware that her own 90s bowl cut won’t age very well, either.

Kelly’s mom arrives in the attic, and Kelly teases her about her old hairstyles, clearly unaware that her own 90s bowl cut won’t age very well, either.Kelly asks, “Mom, you could’ve done so much. Why didn’t you ever go after a career?” She replies, “I was blessed with more opportunities than most. After graduating from college I accepted a position with a big company. I was 24 and had my master’s degree. It was during that time that I met your father.” Kelly is captivated, and her mom continues, “At first I wanted to do both – marry your dad and continue with my career.” Skipping ahead, her mom tells her, “Your father and I decided to do what the Lord wanted us to do, so we began to study the scriptures and learn what the current prophets said on the subject.” They chose to have her dad earn the living while her mom took care of the family. Kelly says, “Yeah, but sometimes it doesn’t seem worth it. All the cooking and cleaning and laundry.” (Kelly can sense that her mom’s life is at least somewhat unfulfilling.) Her mom says, “Hey, I do a lot more than that!”, and shows her a box of letters and drawings from her kids.

Here they look at old cards and letters together, which are very sweet but not relevant to the decision she’s making. Did the kids refuse to make Father’s Day cards for their dad because he had a job?

Here they look at old cards and letters together, which are very sweet but not relevant to the decision she’s making. Did the kids refuse to make Father’s Day cards for their dad because he had a job?Kelly’s mom pulls out a letter from Kelly’s older brother after he left on his mission. In it he admits how ungrateful he was for everything she did for him growing up, and how much of her life probably wasn’t very exciting. He acknowledges that staying at home and raising kids wasn’t easy for her, but thanks her for doing it anyway. He ends the letter by saying that when he finds the right woman to marry, he hopes she’s exactly like his mom.

Her mom tells Kelly that she wouldn’t trade any of her memories for all the money a career could offer her.

”Don’t reach for the stars, honey.” “Thanks for the talk, Mom.” (JK, she didn’t say exactly that – but it was pretty close.)

”Don’t reach for the stars, honey.” “Thanks for the talk, Mom.” (JK, she didn’t say exactly that – but it was pretty close.)I am a little stunned by this. In this church produced film they admit right out loud that the mother’s life often wasn’t pleasant, but that message is paradoxically presented against a background of heartwarming music. As a young woman absorbing this message, I was being told that my future as a stay-at-home mom would frequently be unfulfilling, but that I should be happy anyway.

Kelly asks her mom what she should do about her own schooling. Her mom says to keep at it, because her own schooling (the master’s degree she abandoned) helped her become a better mom. (I was surprised her mom didn’t also mention the hot guys she’d meet in her religion classes at BYU.) Kelly thanks her mom, and they hug. Emotional music plays as Kelly makes the decision to be a stay-at-home mom, not a career woman. It doesn’t matter that she’s only seventeen and might not meet a cute RM into girls with bowl cuts for another decade or so.

The final lyrics are:

“As I prepare for motherhood and children I may raise, Be near me Lord, that I may teach, inspire in loving ways. Help me to walk the path that brings my children back to Thee, That we’ll find joy throughout our lives, together on our way.

And I will prepare to fill woman’s role (not get a paid for any work you do), Accept the Lord’s will with all of my soul. I’ll raise children up, I’ll love them, I’ll lead (except at church), And I’ll take the time to bring them to Thee. And as I prepare for children to raise, Be near me that I may bring them to Thee.”

A montage of Kelly goes from her studying a textbook to studying the scriptures, a clear representation of her shift away from Satan’s evil plan to turn girls into scientists.

A montage of Kelly goes from her studying a textbook to studying the scriptures, a clear representation of her shift away from Satan’s evil plan to turn girls into scientists.I see myself in Kelly – I wanted achievement and a career, but concluded it was a temptation from Satan that I shouldn’t pursue. Looking back, I think her teacher and best friend were actually the heroes (not the villains) in her story. Kelly was a teenager, and it was absolutely the right time in her life to focus on herself and her own career goals. A husband and family may or may not come, and if they do her own career goals are still equally as important as her husband’s.

Nowadays this just looks like a cheesy film from the 90s with silly music and goofy outfits and acting. But back then, to my teenage self, this felt like a message from God directly to me. Camille Johnson’s declaration that she felt free to follow her own personal revelation baffles me. The insistence by so many women in the church that this was always fine baffles me even more!

I hate the feeling of being gaslit by old friends and church leaders (and the cat on my lap hates it, too). Acknowledging and apologizing for what happened to so many of us would go a very long way, but instead both our female and priesthood leaders are choosing to pretend it simply never happened.

(I recently wrote another blog post about my experience growing up female and being encouraged to set aside career ambitions here: I Might’ve Been a Rocket Scientist (Like My Dad), But I Was a Girl – Exponent II)

Thoughts On Community

We slaughtered two pigs over the weekend on our small hobby farm in New England. Don’t worry, no further details about that.

Our resident expert, veteran of 30+ pigs, ran the two-day operation. From procuring the proper tools to demonstrating the more technical tasks, our fearless leader took a group of newbies and made us an effective team.

Our expert is a small, compact, and impressive woman who, at any given moment, had all the men around her, deferring to her, learning from her, and following her directions. Whether it was an anatomy lesson for interested kids, stepping back to let people clumsily practice new skills, or demonstrating a difficult cut, the depth of experience and wisdom she brought to the process made for a very successful day.

This freezer was empty when we began…

This freezer was empty when we began…The butchering process took us almost 12 hours. With seven adults and 10 children aged 2 to 11, we had a full house and still needed every helping hand we could get.

Because I didn’t want to become intimately acquainted with butchering, I took on a support role. I managed the kids, including a potty-training toddler and big kids who dug to China when I had them dig holes for our new apple trees. The kitchen had to stay clean and accessible; bowls, soap, and water needed to be procured; towels and rags needed to be washed, and first aid had to be administered (three nips with knives, no maiming).

Canned pastry lard

Canned pastry lard Then there was feeding the hordes breakfast and lunch, processing the leaf fat to make into pastry lard, vacuum sealing all of the cuts, and the clean up when we finally reached the end of the butchering.

At the end of the day, we all collapsed, but there was pride in that exhaustion, in work done well, and a tangible accomplishment. That night I fell asleep so quickly I didn’t even put my phone on a charger.

The work of any community is bookended by the twin roles of leading and supporting. It’s why the work of care is so integral, especially in partnership with leadership. We needed someone with knowledge and experience to tell us what to do. We needed someone with wisdom and experience to make sure the ship kept running. There is something powerful in both these roles being held by women.

In our little local community, leading and supporting felt circular, equitable. We decided on our ad-hoc roles based on knowledge, expertise, and personal preference. The next time we all come together, maybe to build a fence or plant a garden, we’ll likely juggle our roles to fit the task, our expertise, and personal preferences. Just because I did the work of care this time around doesn’t mean that’s what I’ll do next time.

I can’t help but compare my community experience outside the church to the community within the church, where gender roles are prescribed, hierarchy is top down, and rigid rules govern our practices.

We can do hard work in the church, and I love my small local community of church people as individuals. But what we’re able to accomplish as a local ward is so much smaller, so much less than I think it could be. There are so many unmet needs, so many opportunities that go unrecognized, because our rigid hierarchy and gender roles constrain us.

There is less joy, less pride in accomplishment, less meaning in performing work somehow in the church system. At church, I’m so worried about overstepping that I find myself paralyzed. I’m frustrated by that inertia. I’m never quite sure what sort of tangible outcomes come from all my church labor. I feel resentment in taking on the work of care in a community that prescribes a narrow role for women.

At church, I feel like I must wait to be asked and then only do what I’ve been asked to do. To have an original idea, to want to contribute in a way I’m capable and motivated to contribute to my community, I’d have to get a bishopric member to hear me, see me, understand me, and approve of me. It’s exhausting to even contemplate.

I’m so tired of feeling guilty, for feeling like I’ve stepped out of line, when I do attempt to contribute outside my narrowly prescribed calling. I’m tired of trying to fit in a box that’s too small.

I would like to feel at church like I did over our butchering weekend; that what I contribute matters and that I have the agency to find the right role rather than the prescribed role.

What would our organizations look like without top-down hierarchical practices? What would our organizations be able to accomplish if we could volunteer rather than wait to be called?

The possibilities seem limitless. The opportunities to serve and be served multiplied. And I hope I would fall into my bed asleep so quickly that I would forget to charge my phone.

Photo by Elaine Casap on Unsplash

May 6, 2024

Forgive Us Our Debts

“Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.”

Matthew 6:12

Accounting metaphors run throughout the gospel. In the Lord’s Prayer, debt is used as a metaphor for sin. In other places in scripture, Jesus is spoken of as remitting (i.e. paying a bill for) our sins. When I was explaining the concept of grace and sin to a classmate who had not grown up in a Christian society, the metaphor I used was that repentance erases our sin the same way bankruptcy erases our debt.

Money is one of the last taboos in American culture. I work for the government, so my salary is a matter of public record. My colleagues all make the same amount, and we all know it. We still don’t talk about it!

That said, I’m going to talk about money today. Or rather, the time when I had a severe lack of it, and the fallout from that whole situation.

I used to own a small business. It was profitable, and I made enough money to support myself and to create jobs for an employee and a small handful of contractors. Then Covid happened. I kept thinking that the economic devastation wrought on my business would be temporary and things would look up soon. I availed myself of the aid available, and I borrowed against future earnings to keep the present afloat.

Things weren’t temporary. The business went under and I had to get a job. I was able to land my dream job, so I figured I would just pick up and keep going. But even with a good salary, I was struggling under the weight of the debt I had taken on back when I thought I could save my business. My largest creditor, one who was known for being tenacious and unreasonable, began to hound me and ultimately demanded immediate repayment of what was supposed to be a 30 year loan. I called a lawyer who specialized in negotiating settlements with this specific creditor. He listened to my situation and told me that he couldn’t help me. I was in too far over my head. He said I needed to talk to a bankruptcy attorney instead.

I reached out to my professional network and got a recommendation. I set up a consultation with a lawyer, and after talking with him, we made a plan, and I decided to hire him to help me. For a brief moment, I considered handling it myself. After all, I went to law school. But I realized that this was too important to risk messing up, so I wised up and decided to hire someone who knew what he was doing. I have absolutely zero patience with bureaucracy, so it was money well spent to not have to deal with any of that.

Before filing for bankruptcy, I had to take a consumer education course. (This is required by the court.) I decided to treat it like traffic school and not take it personally. It was a ridiculously judgmental and offensive course. Most people who file for bankruptcy do so as a last resort because of medical bills, job loss, divorce, or business failure. The course was all about how not to waste money on frivolous purchases like shoes or fancy cars. At the end, I had to answer a question about what I would do differently in the future to avoid a repeat of this situation. I answered, “In the future, I won’t own a small business during a global pandemic.”

This is the first correlation between bankruptcy and repentance. There’s a lot of judgment heaped on people who are trying to fix things and do better. Everybody has made some regrettable financial decisions in life, and everybody has sinned. Let he who is without a monetary mistake cast the first stone.

I had to spend down my bank account (such as it was, anyway; I wasn’t exactly flush with cash going into it) to a small amount, and I had to stop using my credit cards. I couldn’t even use a card to buy gas or groceries a few days before payday to pay off after payday. It was humbling to have to once again live paycheck to paycheck.

I struggled, and sometimes my bank account had mere pennies on payday (or, on one particularly bad week, a negative number), but through the miracle of community, I never went without. There was a time when my electric bill was due three days before payday and I was $100 short. I tried to sell plasma, but because of a brain injury I suffered a few years ago, I was rejected. I walked out of the plasma center in tears. I messaged a group chat with a few friends asking them if they had any other ideas for quick ways for me to make $100. Without hesitation, one of my friends Venmo’d me the money and said to pay it forward someday. Another time, an acquaintance I hadn’t talked to for probably 15 years (but who I interact with on Facebook) sent me some Bitcoin that when converted to dollars was enough to cover another emergency bill that came up. My debit card number got stolen the day before my mortgage payment was due, and the thieves made off with about half of my mortgage payment. A family member floated me until the bank was able to recover the money. There were other acts of generosity too numerous to detail. The windows of heaven were opened to me.

I have a very strong testimony of food storage. I’ve always had a well-stocked pantry. I’ve spent most of my adult life either working as a temp or being self-employed, so I’ve had highly variable income. That bag of beans or canister of flour in the back of the cupboard has saved me on more than one occasion when there was month left at the end of my money. When friends found out how much I was struggling during the bankruptcy, the first question they always asked me was “Do you need help with groceries?” I was able to tell them that food was the one area where I was doing just fine.

There were people who owed me money when this whole bankruptcy thing started. I kept hoping that they would pay me back. A few hundred here, a few hundred there, and it would have made a difference. But as the process dragged on and on, I kept being reminded of “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.” It was hard. I needed that money. But I also knew that I was getting a much larger sum wiped away and that I would be a grade-A hypocrite if I didn’t let it go.

When I started this whole journey, I had planned on telling almost no one. I told my lawyer, of course. I told my sister and swore her to secrecy. I told one or two close friends. That was it. I call my parents every Sunday, and I managed to get nearly all the way through the bankruptcy before I had to tell them because of the bank account theft. If my bank account hadn’t been stolen, I likely would have never told them. I didn’t want them to worry. (I’m in my 40s and I haven’t lived with my parents for two decades, but I know they still worry about me.)

Shortly after I set this whole process in motion, it was fast Sunday. I hadn’t planned on saying anything, but God marched me out of my pew and up to the pulpit where I said that I paid my tithing faithfully and that my business failed and I had to file bankruptcy. Tithing, while a true gospel principle, does not prevent us from financial hardship, and the windows of heaven being opened does not necessarily mean we will become rich. I don’t know who needed to hear that that day, but I hope someone benefited from it, because it was awkward to stand up and announce to the whole congregation that I had gotten in over my head like that.

I got my court order discharging my debts the day after Easter, which seemed like an appropriate date for it all to wrap up. It felt like a huge weight was lifted off of me. A debt I would never be able to repay under my own power was erased with a few words by someone with the authority to forgive. Go, and sin no more.

May 5, 2024

Camille Johnson and the Missing Parts of her Working Mother Story

I remember talking with Margaret Toscano fifteen or so years ago about the recently published David Paulsen and Martin Pulido article, “A Mother There: A Survey of Historical Teachings about Mother in Heaven,“ which had made a big splash in the Mormon studies world. After all, Margaret had, along with her sister Janice Allred, been warned to stop writing about Heavenly Mother. They continued to do so and both were eventually excommunicated. But here was this new article analyzing hundreds of church leaders’ statements about her, published in BYU Studies of all places. What did Margaret make of this, I wanted to know.

I’m sure Margaret had insightful things to say about the article, but the one thing I still remember distinctly is that she said that that article hurt a little. It hurt because it seemed to imply there really was never any “sacred silence” being enforced by church authorities about Heavenly Mother discourse and theology. It hurt because it ignored the severe price women like her had paid in the past for thinking, talking, and theologizing about Mormonism’s feminine divine. It hurt because it felt like it was erasing her experience.

Margaret’s reaction may help explain my own mixed feelings about Camille Johnson’s recent talk at the BYU Women’s Conference, in which she spoke about pursuing her career and motherhood simultaneously. Tamarra Kemsley has a great writeup on it in the Tribune (which particularly focuses on Johnson’s encouragement to women to have children, a topic I won’t be addressing here), and a quote from the talk has been featured the Church’s Instagram. In this talk, Johnson said:

“I pursued an education, both undergraduate and a law degree. I was married midway through my legal education. I had my first son the year after I passed the bar. I had babies, and my husband and I loved and nurtured them while we were both working. It was busy, sometimes hectic; we were stretched and sometimes tired. I supported him, and he supported me. Family was, and still is, our top priority. My husband and I sought inspiration in these choices and in the timing. It was what we felt impressed to do. We were trying to let God prevail.

“From a financial and professional perspective, it would have made sense to put off having children until I was more established in my career. In letting God prevail, we sometimes do things that others can’t make sense of.

“I juggled pregnancy, having babies, nurturing children, carpool, Little League, Church responsibilities, being a supportive spouse, and my professional pursuits. It was a joyful juggle I wouldn’t change. We felt confident in our course because we were letting God prevail.”

I feel, maybe not hurt so much, but more a sense of consternation that a significant part of the story has been left out.

Don’t get me wrong. I think it’s fantastic that President Johnson followed her own conscience and figured out a way to participate in her career while having kids. I love that she’s laying this path out as a respected possibility for Mormon mothers. And I think she’s also setting out a great example of placing primacy on own relationship with deity. All very good things.

But a huge part of her story as a working LDS mother in the 1980s and 90s is glaringly missing. What about all those authoritative messages that she heard loud and clear in her formative years that emphasized the evils of working motherhood? She would have been in her mid-twenties in 1987, pursuing her law education or career, when President Benson quoted extensively from President Kimball’s 1977 “Mothers, Come Home” talk, saying:

“Wives, come home from the typewriter, the laundry, the nursing, come home from the factory, the café. No career approaches in importance that of wife, homemaker, mother—cooking meals, washing dishes, making beds for one’s precious husband and children. Come home, wives, to your husbands. Make home a heaven for them. Come home, wives, to your children, born and unborn.”

and

“The husband is expected to support his family and only in an emergency should a wife secure outside employment. Her place is in the home, to build the home into a heaven of delight. Numerous divorces can be traced directly to the day when the wife left the home and went out into the world into employment.”

She would have been raised in the era when church leaders were saying things like:

“Earning a few dollars more for luxuries cloaked in the masquerade of necessity – or a so-called opportunity for self-development of talents in the business world, a chance to get away from the mundane responsibilities of the home – these are all satanic substitutes for clear thinking.” (H. Burke Peterson, 1974)

She would have been about twenty or so when Ezra Taft Benson said, “It is a misguided idea that a woman should leave the home, where there is a husband and children present, to prepare educationally and financially for an unforeseen eventuality.”

Those messages were real and pervasive in North American Mormonism during this time period. That rhetoric absolutely influenced women’s experience with Mormonism and affected not only their life choices, but also their feelings of self-worth, their sense of guilt, and the expansiveness through which they could view the future and their place in it.

Even though I was a teen in the 1990s when working mother rhetoric was softening a bit, I too felt the weight of it. I have no doubt this discourse influenced some of my choices in my twenties and encouraged me to aim lower professionally than I might have otherwise. And as for the women living through that moment in 1987 when President Benson told mothers to come home from the workplace, well, we know the devastation that incurred. Lavina Fielding Anderson, examining the repercussions of Benson’s 1987 “To the Mothers in Zion” talk, wrote in a 1988 Dialogue article:

“Overwhelmingly, the reaction I have heard from women has been one of pain and of anger, whether they have been employed or not. One woman, who has worked all her adult life and has five children, said that her husband, who was a bishop, had been besieged during the week following the address by women full of hurt and resentment.” (p. 105)

Authoritative messages about the evils of mothers working had real impact on the lives of LDS women. Because of them, we very well may have lost, to a significant degree, a generation of LDS women in North America developing careers and therefore decreasing their own financial vulnerability. I’m sure we all know middle-aged or older LDS women whose marriages ended and who were left in terrifyingly vulnerable positions, having to try to reenter the workplace after decades of not being in it.

So what I want to know is: how did President Johnson metabolize those messages? How did she live “joyful[ly],” without regret, guilt, and self-recrimination as a working mother in the 1980s and 90s, given these very strong currents telling her that her choices were selfish and would possibly bring calamity on her family?

Again, I’m glad she talked positively about being a working mother. This is a good rhetorical shift. I celebrate a future in which Mormon mothers are less torn up over the work-motherhood issue, when they realize that it’s absolutely valid and righteous to pursue both simultaneously.

But I don’t think we should forget the distance we’ve traveled to get to this moment. As with many other topics pertaining to the church, it just doesn’t help to ignore past reality. Let’s acknowledge the difficulties, the contradictions, and the ways women have had to wrestle with God, conscience, desires, and authority in the face of negative rhetoric from church leaders about working mothers. Let’s acknowledge the fact that so many statements from church leaders in years past emerged in specific cultural contexts and were reflections of their time and people’s limited understandings in that time. Let’s acknowledge progress as women are encouraged to decide for themselves, in concert with their conscience and inspiration, the path and pattern of their lives.

This talk was an important start to President Johnson’s working mother story. But LDS women now are craving to hear the rest of her story, including the messy and difficult parts. The parts where she confronted head-on authoritative rhetoric that critiqued and misunderstood her choices, and where she learned to place primacy on her own inspiration. Now that will be a story I’ll be excited to hear.

May 4, 2024

Our Bloggers Recommend: What Martin Luther King Jr. Knew About Crime and Mental Illness

I’m a researcher who has done a lot of work understanding issues faced by families who have been impacted by incarceration. The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world and most scholars agree that the way we lock people up is not helping families thrive. Children of incarcerated parents face a host of issues that would be better if the parents were given help rather than being taken away from their kids.

So, I was glad to see this NYTimes opinion piece written by a NY District Attorney. He shares stats such as people with severe mental illness are more likely to encounter law enforcement than receive mental health treatment and approximately half of people in NY jails/prisons have been diagnosed with mental illness.

If we believe in supporting families and children, we need to create communities where people get the support they need! Please, take a moment to read this article (May is mental health awareness month!) and think about what you can do to better create a community where families are supported.