Exponent II's Blog, page 258

July 2, 2018

Gender Roles Are a Result of the Fall

“For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.” 1 Corinthians 15:22

In the beginning, God created a world where man and woman were perfectly equal. Both were created in the image of God, neither above the other. There were no gender roles – no “you must do this because you are a man and you must do that because you are a woman.”

Then Satan came and threw a wrench into everything.

We talk about the results of Satan’s meddling as a “fall”. A fall implies a transition to a lesser state. The fall introduced sin and death into the world. It also introduced gender roles. Far from being the will of God, gender roles are a telestial invention, yet another messed up part of living in this lone and dreary world. God is good, and a good Being does not subjugate half of humanity to the other half for all eternity just because a pair of people ate a fruit they were told not to eat. [1]

When God describes the condition of the newly fallen world to Adam and Eve, God isn’t describing the blessed and eternal state of how things should be. What we get is a recitation of the state of mortality – the warning label on Earth life.

Here are some of the effects of the fall that we see in the scriptural account:

Adam is told that he will have to sweat and toil in order to eat

Eve is told that she will have pain in childbirth

Eve is told that Adam will seek to rule over her

Sin is introduced into the world

Death is introduced into the world

The Good News is that Jesus came to reverse the effects of the fall and to restore us to the equality that existed at the time of the creation. We talk a lot at church about how Jesus saves us from sin and death. We also understand that advances in science are gifts from God to improve our lives. Many fewer people have to scrape out an existence of subsistence farming. Many fewer people experience pain and death in childbirth. We rightly rejoice in these developments.

We see the other effects of the fall mitigated, yet people still insist that female subjugation is the will of God.

How do we ascertain the will of God toward women? By observing the example of Jesus Christ, who is God With Us. [2] Jesus said “the words that I speak unto you I speak not of myself: but the Father that dwelleth in me, He doeth the works.” [3]

Jesus rejected gender roles. He treated women with the dignity, equality, and respect that is owed to individuals who bear the image of God. Three of the most striking examples are how he related to Mary of Bethany when she wanted to learn the word, how he replied to a congregant who praised His mother Mary for her fertility, and how He described Himself.

Mary of Bethany

Mary, sister of Martha and Lazarus, wanted to sit at the feet of Jesus and learn the word of God. We often read the story as a domestic squabble between sisters about who was going to do the dishes, but the story is much more revolutionary than that. At the time, the privilege of sitting at the feet of a Rabbi and learning the Torah was reserved solely for men. Mary was transgressing the gender role society had imposed upon her. Martha approached Jesus confidently, sure that Jesus would back up her attempt to enforce gender roles on Mary – because after all, everyone knew gender roles came from God. Jesus responded radically. While he was, as always, kind and loving to all parties involved, he made it clear that Mary was not doing anything wrong by seeking to do something that society, even religious society, had reserved for men. He praised Mary for her choice. “Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her.” [4]

The congregant who praised Mary of Nazareth

Jesus preached a sermon that those assembled received with joy. At the end of the sermon, a woman in the congregation was so moved that she exclaimed about Jesus “Blessed is the womb that bare thee, and the paps which thou hast sucked.” [5] This unnamed woman expressed her joy at the message of Jesus by praising the breasts and uterus of Mary – reducing her to a reproductive object. Basically, Mary was praiseworthy because she was fertile and produced a righteous son. Jesus responded, again kindly and gently, that praiseworthiness is not a result of fertility. It is a result of righteousness. “[R]ather, blessed are they that hear the word of God, and keep it.” [6] A woman’s honor does not come from her body, her fertility, or the life choices of her children.

How Jesus described Himself

When Jesus described His despair at the wickedness of society, lamenting that He wishes He could have done more to save them, He used maternal imagery. ” O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets, and stonest them which are sent unto thee, how often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye would not!” [7] The Son of God chose to describe His love for humanity in terms society would deem female. If gender roles came from God, why would God made flesh transgress them?

Conclusion

When Jesus taught us how to pray, one of the things He instructed us to pray for is “thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven”. [8] As we see from the life and ministry of Jesus, assigning people to roles and tasks based on gender is not the will of God. And when we become Christians, we are to reject those roles. We are reminded that “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” [9]

If someone were to assert that God requires all men to be farmers because God told Adam at the fall that he would till the earth, we would laugh at the ridiculous argument. Asserting that God requires women to be subordinate to men and to devote their pursuits solely to hearth and home because of what God told Eve is equally ridiculous. It’s convenient to those in power, but it is in contradiction to the example of Jesus, who was perfect.

We can’t baptize inequality and call it good. Declaring gender roles to be the will of God is taking the name of God in vain. Gender roles came about as a product of a fallen world. Jesus came to remove the effects of the fall, so insisting that God requires adherence to gender roles is a rejection of the marvelous atoning power of Christ.

——-

[1] Not to mention, in Mormon theology, we’re taught that Eve did a good thing, not a bad thing, so punishing her, and by extension all other women, for doing a good thing is illogical and ridiculous. It also flies in the face of the spirit of the Second Article of Faith. If men aren’t punished for what Adam did, why would women be punished for what Eve did?

[2] Matthew 1:23 – One of the names of Jesus is Emmanuel, which means God With Us

[3] John 14:10

[4] Luke 10:42

[5] Luke 11:27

[6] Luke 11:28

[7] Matthew 23:37

[8] Matthew 6:10

[9] Galatians 3:28, emphasis added

July 1, 2018

Guest Post: Evolving Thoughts on Immigrants and Refugees

[image error]by Charlotte Shurtz

I grew up in a small, conservative Arizona town where I heard stories of families who were tired of finding the corpses of illegal immigrants on their ranches from my friends. They were fed up with repeatedly fixing fences cut by smugglers and worrying about drug cartels hiding on their land. I heard stories of illegal immigrants who were convicted and deported, but were back in the United States committing more crimes by the end of the next week. I read in the news that Sheriff Joe Arpaio thought illegal immigrants should be prosecuted rather than given amnesty. He herded them up, gave the men pink underwear, and collected them in tents in Phoenix’s withering heat with only the weather channel for entertainment. At orchestra practice, church, and community events, I heard respected adults complain that immigrants stole jobs from United States citizens. Everyone I knew passionately supported maintaining a strong southern border and firmly punishing anyone who crossed it illegally, so I did, too.

Then, just before Thanksgiving the year I turned 19, I moved to Minnesota, the state with the highest concentration of refugees and immigrants, where families from all over the world invited me into their homes, shared their traditional food, and taught me about the beliefs and symbols they held sacred. I ate kielbasa and sauerkraut with a family from Ukraine, tasted fatteh from Egypt, tried pho from Vietnam and falafel from Greece, gobbled up pupusas from El Salvador, and stuffed myself on tinga and pasole from Mexico. I ceremonially washed myself for evening prayers with a Muslim woman and her daughters, accepted the gifts of a beautifully bound Qur’an and a handmade rosary, joined an Ent seeker in chanting “ooo” softer and softer until our voices faded away, and volunteered at a homeless shelter.

Each person I met had a unique story. Nurse Mia cried after strikers on a bridge were attacked and she watched friend after friend die because the Cambodian hospital she worked at didn’t have enough oxygen for all the patients. Josefina was sent to prison after seeking justice for her father’s mafia-orchestrated murder. She sold her only cow to pay lawyer fees, but it took years before she was able to return to her children, and even longer before she was able to escape the social stigma in her small town in Honduras by coming to the United States. While trying to leave Mexico after a corrupt election, the Candelaria family was attacked by the police and then waylaid by a gang. Wilfredo, a respected professor of history, fled a South American country with his family because his warnings against repeating history were met with death threats. And then there was the young, crippled, and scarred girl from somewhere in Africa whose family didn’t speak any English. Her mother conveyed through a translator that she had been raped, attacked with acid, and then left to die by insurgents. They were asylum seekers, refugees, political exiles, and immigrants whose lives had been hellish at times.

They became my friends and I cried with them and for them.

But it was Jamie’s story that most wrenched my heart.

On a Friday afternoon in early April, she said a prayer, called an old friend, loaded her children into her jeep, and, leaving all her belongings, drove to her friend’s apartment in south Minneapolis. The next day I stood in the echoing hall that smelled like a mix of curry and rice and corn tortillas and chipotle in adobo sauce, waiting to see if someone would open the door to apartment 117. When the door opened, I met Jamie.

As young teenagers, she and her brother lived on the streets because their parents could no longer feed them. Hearing from friends that in the United States they could make more money, they saved until they were able to pay a coyote to bring them across the border. Together they wandered from place to place, eventually arriving in Minnesota where they both found jobs.

There Jamie met a handsome, blue-eyed American who flattered her with his attentions; the brilliant flowers and the warm smiles, the dancing at clubs and the dinners at fancy restaurants convinced her that he loved her. She moved in with him. Her brother returned to Mexico, but she stayed. Then things changed. The handsome, blue-eyed American started leaving bruises on her back, her arms, her face. He took her money, brought drunken fights and drugs into the house, beat her in front of her children, and destroyed her confidence. He allowed other men to ogle her little girl, touch her, and then asked for money or drugs in exchange. When she protested, he reminded her that she was an “illegal” and smiled as he threatened to report her.

A few days after I met her at her friend’s apartment, Jamie and I returned to his house, in a blue pickup driven by one of my friends. Jamie slid down from the truck in front of the house they had shared for six years, clutching the house key in her hand. As we bagged all her belongings, the kids’ toys and backpacks, she searched for the birth certificates and immunization records she had hidden. She walked out to the pickup and climbed into the back seat next to me.

Their clothes were tumbled into bags. She would have to sort them out later. Her daughter’s dolls were buried under her son’s cars, except for one Barbie lying in the back of a dump truck. They would be happy to have their toys again. The kids’ backpacks were in the back of the pickup, stuffed with wrinkled homework. Homework her kids wouldn’t turn in because they would have to go to a new school. And in her hand she held their birth certificates and immunization records. Proof that her kids were born in the United States, certificates of their legitimacy, tickets that would let them get scholarships to college and house loans after they grew up.

As we drove away, her phone rang. She stared at it a moment, then touched the green phone symbol. I heard a man’s voice yelling, threatening her. Crying, Jamie whispered, “Lo siento.” and hung up.

She looked down at her hands, wrinkled though she was young, chapped from work, tired and worn like her spirit. She was glad to be leaving the monster he had become, for both her own and her children’s sakes. They needed a better life than she could give if she stayed with him. But it would be hard to shape a new life, a new normal. A new apartment. A new job, maybe two. For her kids, a new school, new friends.

For months afterwards she would awaken, reliving his abuse, seeing her children’s terrified faces, remembering his angry threats on the phone. Then she would slip from her bed, checking on each of her children sleeping on the couch or on the floor, tucking the blankets tighter around them, relocking the door, reminding herself that he was gone, that they had started over. Eventually the dreams would stop, but for years she would still jump when she heard a voice that reminded her of his.

Jamie’s story has haunted me ever since. I wonder what would happen if she were deported. What would happen to her young children who are United States citizens? Would they go back to their father who abuses both substances and his children? Would they go with Jamie to Mexico, although they don’t speak much Spanish and were born in the United States? Would she be able to provide for them there like she has here? Would they be able to attend college as Jamie hopes for them to do?

And then I ask myself, what about all the others I met in Minnesota? The refugees, the undocumented residents, the asylum seekers. Many came to the United States to survive and give their children a chance to survive. They care about their families, work hard to feed their children, and want their children to gain an education. If they, as I once would have said, went, “back where they belong,” what would happen to them? Is it harsh to wish that they would leave when their families belong here more than there? Is it cruel to wish they would “go back” when going back means living somewhere their children have never been?

In the last few weeks, I have started asking myself additional questions about those who are currently trying to immigrate or seek asylum in the United States. Like many of the friends I made while living in Minnesota, they are trying to escape horrible conditions to save their own and their children’s lives. As a nation founded by immigrants, why are we not welcoming families seeking asylum with open arms instead of prosecuting them for entry? What can I do to welcome immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers? How can I let my government leaders know that I want them to be welcomed? How can I make a difference?

Charlotte Shurtz is a senior at Brigham Young University, where she studies English and Civic Engagement. She enjoys learning to cook foods from different cultures and going on hikes.

June 30, 2018

Why Good People do Bad Things

I’ve been reading about the massacre at Mountain Meadows on September 11, 1857. South Utah Mormons disguised as native Americans and their Paiute allies laid siege on a wagon train from Arkansas. The 5 day siege culminated in the murder of about 120 individuals, including men, women, and children. Mormon militia promised safe passage to the company now low on food and water and got the group to comply with their instructions, the weapons were discarded, men were separated from the women and children. Then all the party but 17 young children were slaughtered. Their livestock and property were seized and the bodies buried in a shallow mass grave. It is horrifying to read of these events. Attempts to justify what happened are just as appalling.

I interpret this story as a cautionary tale that shows even good people do bad things. We all bear both good and evil fruit. Any of us are susceptible to being drawn into doing horrific things to others. I hope that recognizing and trying to understand the factors involved can help prevent them from recurring.

Why do good people do bad things? I’m thinking primarily about how an otherwise peaceable upstanding citizen can be driven to violent acts. To better understand the social psychology involved, I have also reviewed the Milgram experiment and the Stanford Prison experiment. Here are the factors I compiled:

Authoritarianism. The leader is perceived to be ‘good’, respected, and legitimate. Hierarchy may smother individual morality as followers willingly comply with direction, feeling that the authority figure will take responsibility for their actions. Proximity of the leader can affect obedience.

Dehumanizing others. Creating an “enemy” or “us vs. them” ideology. Labeling or demonizing others (calling them animals, criminals, etc.)

Dehumanizing self. Filling a role to the point that the role becomes the identity. Get a feeling of anonymity (sometimes by wearing a uniform, mask, hood, or face paint). Mob mentality takes over, feeling of power over others, lose individuality, minimize individual responsibility (uniform or appearance can also give more status/power to the perceived authority).

Ambiguous expectations of leadership. Unclear instructions, inconsistent enforcement of rules, lack of supervision, no training and no accountability.

Ideology justifying beliefs/actions. This can include relabeling situations or people to legitimize a system of beliefs. Ideologies that create an unwavering certainty of one’s own moral rightness or superiority can contribute to violent behavior.

Mental state. Those experiencing stress, fear, boredom, exhaustion, deprivation/poverty, are more susceptible to suggestion.

Violent environment and/or rhetoric. This includes incremental steps toward the commission of a harmful act start with something more trivial steps and slowly become more malignant. Aggressive acts may be labeled as deserved or even as ‘helping’ the victim.

Peer pressure. This provides a strong deterrent to dissent. Individuals surrounded by models of social compliance are less likely to speak out. Exiting the situation could be difficult or dangerous.

Many of these factors contributed in the case of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I feel like the best bet to avoid being caught up in a moral disaster is to be on guard with these points.

Be careful about who you follow. Rather than surrendering moral authority to a leader, choose your own actions, and claim responsibility for the results of those actions. Encourage others to do the same.

Listen carefully and be on alert when you hear others being dehumanized or labeled. Be wary of messages proclaiming certainty or superiority. Maintain openness to the possibility of being wrong on any given issue.

Maintain a distinction between yourself and the roles you fill. Remember who you are. Maintain your individuality and identity without succumbing to the lure anonymity, which is often also a lure to behaving badly.

Expect clear instructions from those in leadership, regulated enforcement of rules, appropriate supervision, training, and accountability.

Listen and pay attention when ideologies are used to justify inappropriate actions. Pay attention to how stories are retold, and see if they are reframing it in a dishonest way to justify persecuting an ‘other’.

Be mindful of your mental state. If you are feeling stress, fear, boredom, exhaustion, or other deprivation, recognize that you are more susceptible to suggestion. Try to care for yourself so you will not be in that state long, and be wary of those that would influence you when you are vulnerable.

Pay attention to violent rhetoric. Question statements that say anyone is deserving of violence done to them.

Be wary of negative peer pressure, and remember it can also work for good. Remember that others will also be more likely to disobey authority when they see it done. Your act of noncompliance may change the tide.

Sometimes we feel powerless to affect change. When we see injustice, we cringe, but don’t feel like we can do anything. Even speaking up on a small-scale can sometimes touch hearts. This is a small, silly thing, but I saw a meme posted by my husband’s aunt recently that referred to certain people as ‘illegals’. I was about to unfollow her on Facebook because I felt like that was a hateful thing to post. I have personally been heartbroken about immigrant families being separated from their children. Instead of quietly unfollowing, I wrote “I don’t like seeing people referred to as “illegals”, I feel like it is dehumanizing.” I was scared. I knew any of my husband’s family might see what I wrote. Later in the day I checked back to see what people were saying about it. She had taken down the meme! I am not sure whether her feelings had changed, but my feelings about my ability to make a difference (however small) did change.

Speak up as a voice of reason. When you see these risk factors, draw attention to them. Speak up to support morality. Don’t suppress your conscience to avoid being seen as a ‘troublemaker’ or to ‘fit in’. Be willing to speak dissent when necessary to correct problems in society. You can do so lovingly and truthfully. Jesus spoke up for the persecuted, not the leaders and lawgivers, not even the law.

Notes:

The Mountain Meadows Massacre – Juanita Brooks

Massacre at Mountain Meadows – Walker, Turley, & Leonard

Psychologist Stanley Milgram’s experiment demonstrated that those given an order (by someone in a perceived position of authority) delivered what they believed to be extreme levels of electrical shock to other study participants for answering questions incorrectly. https://simplypsychology.org/milgram.html

In Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison experiment, a group of male college students were assigned roles of prisoners or guards. The guards quickly became brutal and abusive toward prisoners, disregarding the potential harm of their actions on their fellow students. “You don’t need a motive,” Zimbardo said. “All you really need is a situation that facilitates moving across that line of good and evil.” http://www.prisonexp.org/

June 29, 2018

How To Have Difficult Conversations, Part I: Is the Person Safe?

[image error]This is the first of a three-part series about how to navigate difficult conversations. Part I will consist of how to identify whether someone is safe before determining if or how to have a difficult conversation with them. Part II will detail how to engage in a complex talk with someone who is unsafe. Part III will illustrate how to have an effective hard talk with someone you trust enough to be vulnerable with.

Is the person safe?

Most people have both positive and negative qualities. So it’s important to remember that people who are generally unsafe are not all bad. This post is not intended to condemn anyone. In fact, LDS theology teaches that in general everyone will have the opportunity to continue to grow after this life. However, it may be that certain traumas or adverse life experiences, especially if they occur during childhood, may make it difficult or maybe even impossible for a person to change or grow past a certain point in this life. Of course most people who are willing to seek help in working through their early life trauma can often experience healing and can transform their life.

But for those who do not or cannot make that choice, we can hold compassion and love in our hearts even when they exhibit unsafe qualities. At the same time, we do not have to accept abuse or continue relationships with them if they cannot or will not stop harming us or those we love.

The second commandment we are given in the Bible is to “love thy neighbor as thyself” (Matthew 22:39). But implicit in this commandment is the injunction to love oneself first. It’s difficult to love others if we do not know how to show love and compassion for ourselves. In fact, I think the ability to love others may grow out of our experience of learning how to prioritize and care appropriately and lovingly for ourselves.

The following guidelines are an attempt to help you navigate the often murky waters involved in discerning whether someone is safe enough to enter into a difficult conversation with. I hope they can be a kind of lighthouse along the relationship shore to guide you through the sometimes disorienting dynamics of determining whether someone is safe enough to be vulnerable with, or whether it is best to disengage and protect yourself.

What determines whether someone is safe or unsafe?

What follows draws on the wisdom contained in the book Safe People by Dr. Henry Cloud and Dr. John Townsend, as well as an article on Psychology Today about their work on this topic.

The most important aspect of determining whether someone is safe or not is recognizing that a person may appear to be a genuinely kind person but may ultimately be unsafe because of issues they are struggling with. So how do you know if someone is safe?

Unsafe people are dishonest. They consistently lie, tell half-truths, and may twist the truth in an attempt to deceive others into believing something that is simply not true. A safe person is honest. Their words and actions match. (Note: research has demonstrated that everyone lies from time to time. The difference here is a pervasive and overall pattern of behavior that has the effect of misrepresenting reality for the dishonest person’s gain.)

Unsafe people demand trust. Trust develops over time as a result of someone consistently exhibiting caring behavior. Safe people allow trust to be built in this way. Unsafe people often demand that you trust them immediately and may act hurt or defensive if you don’t trust them quickly.

Unsafe people don’t grow. Everyone makes mistakes or has parts of themselves that need improvement. Safe people admit their mistakes, are open to feedback about how their behavior impacts others, and they work to improve themselves over time. They apologize and take steps to change their hurtful behavior. Unsafe people never, or only rarely, admit their mistakes and are often critical of others and defensive when faced with their mistakes. They may initially apologize, express regret, and/or make promises to do better, but ultimately they do not change their hurtful behavior.

Unsafe people avoid facing their issues: instead they may project their problems into you—blaming you for their problematic behavior. It’s much easier to point your finger at someone else than to humbly consider how you may have harmed someone. Safe people take steps to overcome their issues, demonstrate empathy when someone is hurting, and can forgive when appropriate. Unsafe people often lack compassion for others’ pain and hold onto grudges instead of working to forgive others.

Unsafe people use flattery instead of talking with you. Someone who only tells you positive things about yourself is more interested in your liking them than being honest with you. A safe person actively listens to you and engages in a mutual dialogue with you about your concerns. An unsafe person is consistently resistant to hearing your complaints, is often defensive, and may blame you repeatedly for their hurtful behavior.

Unsafe people gaslight, blame, and shame those they harm. Gaslighting is a form of crazy-making. It is any behavior that causes a person to question their sanity. Unsafe people “blame the victim”: they tell you it’s your fault that they hurt you. Unsafe people will often stop at nothing to engage in behavior that will cast those they harm in the poorest light possible. By contrast, safe people take responsibility when they harm you; they apologize and take steps to change their behavior. They “greenlight” who you are by demonstrating profound compassion for where you are in your life journey. They accept you as you are while supporting your individual development and desires to grow.

Stay tuned next month for Part II in this series, “How to Have Difficult Conversations.”

Wendy is a psychoanalyst, licensed clinical social worker, and marriage and family therapist in private practice.

June 28, 2018

In which a Mormon momma decides to go to work

It was almost 18 months ago that my husband finally said, “Aly, maybe you should consider applying for a teaching job for next fall.” He’d made a couple of comments to that effect over the last couple of months (which I’d quickly dismissed), but this time I could tell that his suggestion was sincere. Which is why I immediately exploded into angry tears at him as I launched into the speech I hadn’t even realized I’d already written about why I, a mom of two kids under four, absolutely could not.

To be clear, I was not under the impression that working women were incapable of being good mothers. I remember driving around Rexburg several years before this as a young, single college kid with a friend who, in the course of our conversation, told me with conviction that “God would never give a mother a revelation to work outside the home.”

I’d disagreed. Growing up, I had seen too many examples of good working moms to believe a statement quite as absolute as that. Still, what I did believe (which reflected teachings I’d heard all my life ) was what I still had mentally locked away as truth several years later as I rage-cried at my husband for suggesting that I think about pursuing my dream job. In my mind, in order for it be OK for me to work, one of the following had to apply:

Because of death, divorce, or disability, I needed to be the breadwinner for my family.

Our family would endure serious financial struggles if we didn’t become a dual-income household.

The work was temporary, very part-time, and/or was something I could do from home while my kids napped or whatever.

Serious mental illness made it impossible for me to safely stay home. Or, at the very least…

My husband and I could have flexible enough work schedules to where our kids would always be with one of us, OR one of us had a parent or sibling close enough who could watch them.

When my husband suggested that I teach, neither #1 nor #2 applied. Number 3 was not something I had any interest in, and our situation made #5 impossible.

It’s true that I struggled to be happy as a stay-at-home mom (which is why the idea that I apply for a job was brought up in the first place). Despite the counseling I’d received, the meds I’d been prescribed, the friends we’d made, the community we’d worked to fit in with, and the creative ways I’d found to get all of us out of the house, I felt largely detached from the dynamic, purpose-driven, meaning-making person I’d been before. I spent most days heavy with the guilt I felt at the dread, restlessness, distractibility, and frustration I so often dealt with as a stay-at-home-mom but couldn’t seem to sufficiently manage. And I usually found myself alternating between the extremes of being an emotional wreck and trying to emotionally detach myself from the feeling that I was failing my kids, that I must not really love my daughters that much, or that I must be a deeply selfish person to not find more joy in this thing that so many of my truly lovely stay-at-home friends at least appeared to find with relative ease.

Still, none of what I was feeling was anywhere near serious enough for #4 to really apply. Therefore, I told my husband, nothing about our situation made it OK for me to work.

I can’t remember how or why the conversation took such a turn at this point (maybe because my husband’s response to my speech was especially good, or maybe because I’d unwittingly been thinking in this direction anyway). But by the end of our conversation and for the first time since I’d become a mom three years earlier, I reluctantly agreed to think about it.

What followed was kind of a blur that included a lot of researching, worrying, avoiding, talking with my husband and close friends, and searching through articles and posts on the Aspiring Mormon Women Facebook group and website. I had to work through the deep inadequacy I felt at even considering applying for a job when I hadn’t taught beyond my student teaching and it had been *so long* (five years, but that still felt like an eternity) since I’d earned my degree. And I also had to gently confront the part of me that refused to believe that other people in addition to my husband and me could love and care for our daughters, too; or, rather, that having other caregivers in their lives who weren’t family when I didn’t have a good reason to be working in the first place—that was key—didn’t mean that my kids would be messed up and hate me and their dad for the rest of their lives.

My last struggle with all of this was with God, who I was already on tenuous terms with. Because of various mental and spiritual shifts that had occurred within me over the last few years, God was an entity that I no longer confidently understood how to conceptualize or approach: a presence of love and wisdom that had once been so easy to access but now seemed almost impossible to find. My insecurity there meant that it was easy to believe that the legalistic, supremely disappointed voice that sometimes runs through my thoughts was an accurate representation of how God felt about me working:

“You’d best have a very good reason if you’re going to abandon those precious babies to run off and be a teacher,” I’d hear versions of again and again in my brain.

Then, one night as I sat on my couch scrolling through social media while imagining a bearded God shaking his head at my ingratitude (such mental multi-tasking), I came across this article by “Today’s Parent” Editor-in-Chief Sasha Emmons, written as a letter to her young daughter about why she works.

These words hit me with enough force that I’m going to quote a good chunk of it:

“There are many reasons mommies work,” she writes.

I work because I love it.

I work because scratching the itch to create makes me happy, and that happiness bleeds over into every other area, including how patient and engaged and creative a mother I am…

I work because I did this before you were born, and I’ll still want it to be there after you go off to college.

I work because… you’d never ask your father why he works. His love is a given that long hours at work do nothing to diminish.

I work because even at your young age you’ve absorbed the subtle message that women’s work is less important and valuable—and that the moms who really love their kids don’t do it.

I work because by the time you have your own daughter, I cross my fingers this will not be so.

So, to answer your question: I do love work, but of course I love you and your brother much, much more. If I had to choose, I would choose you guys.

But I’m so happy I don’t have to. And I hope you never do either.

Love, Mom

This working momma’s reasons weren’t unfortunate, and they didn’t seem to be there only because some better, holier Plan A had fallen through. Rather, her reasons were both empowering and compassionate. And as I slowly read through each of them, all of the chaos swirling around inside me—the worries and fears and negative self-talk and preconceived notions of what it meant to be a “good” mom—kind of went quiet. It was one of those rare moments when everything settles and the path forward appears there in the distance, clear and bravely lit, and you’re reminded for maybe the thousandth time that Love is not fearful or small-minded or restricted by the boxes that we humans like to put each other into; that God doesn’t actually have a one-size-fits-all plan for how to go about creating a good life—even if you’re a Mormon mom.

A few notable things have happened between then and now. One is that I did end up getting a teaching job, and another is that it was a really hard year. Moving from a single- to a two-income home forced my husband and me to take a hard look at how we balanced responsibilities and communicated our feelings and prioritized our time, and every member of our family has had to make sometimes painful adjustments. But it is important to note too that this year was also so good. Working through all of the stress and chaos of this past year has made us a stronger and more resilient family in so many ways. And the joy and growth I find in my work not only spills over into my interactions with my family, but has just helped me feel like a whole human again. It’s empowering to realize that you can be more than one thing.

As I write this, I’m aware that there are many mothers in the world who would love to stay home but cannot, and that there are many moms, too, who wish they could work but have circumstances that won’t allow it. I realize that the choices I have are a privilege. If either or both of my daughters become mothers someday, I hope that they will have that same privilege.

If they do, though, I hope that they will understand sooner than I did that that privilege cannot be adequately summarized as a choice between whether a mom will be a good one or a selfish one. Instead, I hope that they will understand that there are a billions ways to be a good mom and awesome human, and that the privilege is being able to choose how to go about writing their own rich, messy, meaningful stories. When my girls someday look back on how their dad and I tried to author ours, I hope that they will be able to see an example that encourages each of them to be thoughtful, deliberate, and brave as they write theirs. And when they’re grown and think back on how their mom chose to work not because she had to but because it made her soul happy, I hope that they’ll see in that a reminder that they too are worthy of creating and pursuing their own dreams.

[image error]

image from stokpic.com

June 26, 2018

Guest Post: Tell me, Grandmother

Photo Credit: Kevin Moore

Tell Me, Grandmother

Grandmother

I want to know…

Did you sit under the cherry tree and learn the ways of everyday feminine holiness at your grandmother’s feet?

Did you have visions of my grandfather before you met him?

Did you give my grandfather his second anointing as he entered your holy of holies?

Did you consider your 40 week pregnancy a 40 week pilgrimage into the holy lands of your soul?

Did your labor consist of wise women, seen and unseen, singing, praying, and blessing your womb’s holy creation into the world?

Did you sing my infant mother heavenly melodies as you administered her own first anointing at your breast?

Did you kneel in your garden and whisper to the wind when you prayed for rain?

Did you stand at the stove and bless my mother’s food to wholeness each day?

Did you sit my mother on your lap and kiss her boo-boos goodbye, infusing them with light energy and the vibrations of love in your soul?

Did you ride the waves of your monthly cycle in an effort to reside in the breadth and depth of your infinite energy?

Did you consider menopause your own descent into the womb’s garden tomb–a glorious invitation to die and rise again a new creature?

I want to know if you ever did these things.

I want to know why you didn’t teach them to me.

====================================================

By: Caroline Crockett Brock. Lover. Mother. Writer. Goddess in Embryo.

June 25, 2018

Guest Post: Choose Ye This Day. . .

I got a message from an old college friend a week or so ago. She had always been a champion of conservative politics, from BYU College Republicans to canvassing for the Romney campaign. A Texas Republican if I’ve ever seen one. And while we had long disagreed on a number of political issues, she was and is a kind, compassionate human being I counted as a true friend.

When she learned of the Family Separation Policy, I watched her via social media take up a sword and actively fight against the callous and cold responses from her uber-conservative friends and family. I offered her solidarity in the form of likes and a few fact-filled comments where I saw space for dialogue. And after a few days she messaged me, a plea filled with anguish and sorrow, “How do we stop this?”

Image of children in a detention facility sleeping on mats with mylar blankets.

As we talked, it was clear she was hoping there was a simple answer. A single policy that could be overturned, a law suit that would prove the governmental actions violated the law, or even an opportunity to “help the one” by flooding child and family detention centers with blankets, toys and funeral potato casseroles. But as I explained to her the legal realities of administrative law, plenary power, and the systemic denial of due process, I had to make it clear. This is just the tip of the iceberg of a deeply-entrenched and sophisticated system designed to dehumanize and marginalize immigrants—especially those with black and brown skin.

See, what we are finally seeing now is nothing new. Not really. The zero-tolerance and family separation policies enacted in the past two months are a particularly heinous variation on a theme, but if you search google for articles about why children and families are being detained, why refugees can’t get asylum, and how ICE and CBP are rife with unchecked abuse and violence, you will be surprised by how many mainstream news articles are dated 2016, 2014, 2011, or earlier.

There are no clean hands, left, right, center or agnostic. We are all complicit in our blindness.

What we are seeing now are the visible manifestations of a necrotic, dehumanizing system that has always been driven more by racism and xenophobia than any other so-called ideal or interest. We are facing that moment when the cancer has spread so wide and deep that the tumors are visiblelly pushing through the skin. And suddenly, we can’t look away.

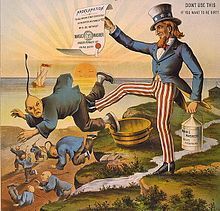

Image of Uncle Sam kicking Chinese immigrants out of the US.

The history of immigration law is the history of our shifting scapegoating against whatever ethnic group presents as simultaneously the most threatening and the most vulnerable among us. Citizenship has historically been withheld or stripped from Black slaves, Native Americans, Chinese workers, and Mexican Americans — overtly, explicitly and without apology. The first major cases you read in immigration law class is Chae Chan Ping — “The Chinese Exclusion Case”—named for the Chinese Exclusion Act which they upheld and ensured that the thousands of chinese laborers who built the impressive US railways could easily be exploited, oppressed, and expelled from the country. Overt racial quotes have given way to xenophobic dog whistles, but this is far from the first time the US government has sought to actively stripped citizenship from people of color and deported them based on skin color and surname.

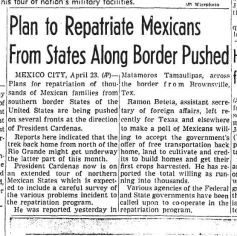

Newspaper clipping

I am the granddaughter of an undocumented Mexican migrant worker on one side and refugees from Nazi Germany on the other. Since law school, I’ve focused my work on immigrant and refugee rights. What I’ve learned is deeply troubling. Beyond the substance of our laws, the system we have designed to destroy any shred of due process is impressive in its efficacy. And the work it is going to take for us to dismantle it and reclaim our own complicit souls is going to take a long, sustained, committed fight.

In this moment — this terrifying, soul-crushing moment — I am inviting you to join that fight. Decide now not simply that separating families is a bridge too far, but that you will allow this moment of moral clarity to plant itself in your heart. Like the seed of faith, let this moment grow into a fierce and fearless commitment to our shared humanity. Decide today that we will no longer allow migrants, refugees, brown and black children to be the acceptable collateral damage in our social and political negotiations.

What can you do? I’m answering that question at Torchlight Legal Communications with information, education, and recommendations on how to fight both the immediate and systemic harm. I welcome your contributions, collaboration and suggestions. “If ye have desires to serve God ye are called to the work.”

Graphic describing how people can help detained/separated families.

Jennifer Gonzalez is a legal communicator, information designer, & immigrant and refugee rights advocate who produces articles and media at Torchlight Legal Communications. She earned a JD at Stanford Law School while exploring human-centered design theory, narrative and storytelling, and documentary filmmaking as a tool for understanding the human impact of law and policy. During her post-JD fellowship, she assisted refugees fleeing gang and cartel violence in Latin America through the North Carolina Immigrant Rights Project and has dabbled in the world of silicon valley startups and legal technology. She has two degrees from BYU (BA and MA in English), but deftly escaped without an MRS and embraces her life as a radical, single, latinx, mormon, feminist bruja and rockstar auntie to her seven niblings.

This article has been cross-posted at Feminist Mormon Housewives.

Here’s the video of Be One, the 40th anniversary celebration of the extension of LDS priesthood and temple worship to people of African descent.

I watched this with my kids and I found it a great way to teach them about this part of our history. My 10-year-old son cried when the narrators told the life stories of African American, African, Jamaican and Brazilian Mormons barred from the temple. The show starts 25 minutes in, after a talk by Elder Oaks.

Dreams of (and for) my daughter

When my only daughter was not yet two years old, I had a vivid dream. It was soon after the emergence of Ordain Women, and I was trying to sort out my feelings on female ordination. I desperately wanted more inclusion for women and girls in authority and decision-making positions, but hadn’t yet made the jump to supporting ordination. I worried about what my daughter would be taught if she never saw women as spiritual role models, and if she never got to fully participate in church ordinances. In the middle of the wrestle, I dreamed that my daughter was standing in the chapel, a few pews ahead of me, with her arm bent at the elbow, waiting to return a sacrament tray to the front of the chapel at the end of the sacrament. She was there with her peers, both boys and girls, participating in a ritual that is currently for boys only.

When I woke up, I felt a profound sense of peace. I don’t usually think of my dreams as visions; I’ve had far too many wacky and/or terrifying dreams to read too much into them. But this one felt more visionary. It felt like God was telling me to stay the course, that changes were coming, and that my daughter would be included in church administration going forward.

When my daughter was three, she would reverently fold her arms and close her eyes during the Sacrament prayer. But she would also softly – almost imperceptibly – repeat the words of the sacrament prayer as they were said every single week. At first she would say each phrase after they were said, but by the time she was four, she could say them in unison with the priest offering the prayer. She knew the sacrament prayers better than I ever have, and would occasionally start repeating them under her breath as she played with her dolls or ponies or even just as we drove to the grocery store.

My daughter is five now. She no longer repeats the sacrament prayers (at least not aloud), but she is very focused and reverently waits for the sacrament to be passed to our family. She never lets the tray pass down the pew without putting her hand on it, helping to pass it along.

Yester[image error]day, as the sacrament was being passed, I looked over to see her standing straight up, with her arm bent at the elbow, perfectly mimicking the deacons who were standing in the chapel, waiting to return their trays to the front of the chapel. I gasped just a little, because she looked like a miniature form of herself during that dream from years ago.

Now, as you can probably tell, my daughter is quite the mimic. She engages in pretend play exponentially more than her brothers ever did. She dances around the house and tells me that someday she’ll be a ballerina. She draws rainbows on any spare scrap piece of paper, and gives them as gifts to people in our family and neighbors. She regularly dresses up as a doctor and gives us all exams, which is adorable until you realize that the cat is covered in band-aids (apparently the cat was very sick). Last week, an adult asked her what she wants to be when she grows up, and she said, “I’m going to be a doctor and an artist and a ballerina. I’m going to do all three. I’ll be very busy.”

I love watching her understand and experience the world this way. I love that she truly believes that she can be all three things if she puts her mind to it. But I worry for the day that she realizes that her expert studying in sacrament-passing isn’t enough to be qualified to pass it. I worry about the day that she subtly understands why she can’t pass it, and it’s not because she’s not skilled enough or unwilling, but that she was just born out of it. I think of somebody telling her that girls can’t be artists, or that girls can’t be doctors, or that girls can’t be ballerinas, and I’m filled with a visceral anger at the arbitrary nature of those limits. But with priesthood functions, I feel a combination of dread and passive defeat. I want to believe that women and girls will be more included in the future. I really, really, want to hope for that. I want to believe that the brethren will heed Bonnie Oscarson’s impassioned plea to incorporate women and girls into church functions. I just have learned to keep my optimism guarded, protecting myself from what feels like inevitable heartbreak and disappointment. But as I saw my daughter in that perfect pose yesterday, with her arm bent, I pleaded with God in my heart: please let that dream be not just a vision, but a prophecy.

June 24, 2018

Walls

Joshua at Jericho

Before the crumbling walls

A brand new Warrior/Prophet

Saw God by the falls

Are you for us? Or against?

I lead the hosts of God.

Jericho before the war

Was sacred, holy sod

40 years of manna

Hear the ram’s horn sound

Seven years of battle

Walls come tumbling down

(Photo credit: “wall” by rot_grad, license here)