Exponent II's Blog, page 135

August 10, 2021

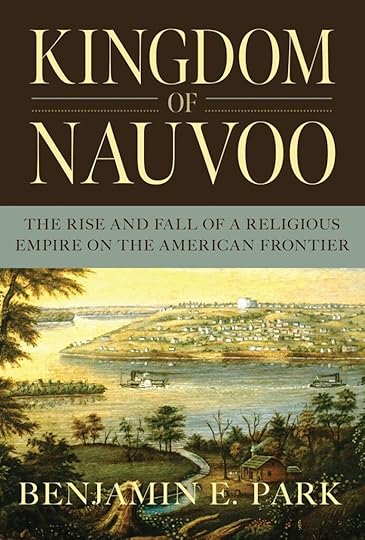

Benjamin E. Park’s Kingdom of Nauvoo

In late February 2020, I joined a couple dozen people for a living room soirée to listen to Benjamin E. Park talk about his new book, Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of A Religious Empire on the American Frontier. Dr. Park, an assistant professor of early American history at Sam Houston State University, situates the mid-19th century city of Nauvoo as an example of the tenuous nature of American democracy for a religious minority on the fringe of American society and geography. How far did freedom of religion extend? Nauvoo tested those limits.

At the event, Park offered an overview of the themes from his book, answered questions, and signed copies. I met several friends I only knew via social media and we chatted over homemade bread with honey butter. While news headlines were becoming more concerning by the day, I certainly did not realize that this would be my last evening out without worrying about masks or social distancing or a devastating global pandemic. Park’s book tour was cut short as university campuses and book stores closed and seemingly the entire world shut down.

It is in this broader context of uncertainty and ramped up anxiety that I first read Kingdom of Nauvoo. And while my personal experience of reading may not be relevant to the content of the book, it highlights to me the brilliance of what Park accomplished. Though it is meticulously researched, the book was published by a national press and is written for a general audience. Clocking in at a slim 279 pages, the book’s narrative moves at a fast clip and remains an interesting and accessible read. At a time when I set aside my own research and writing and mostly sought comfort TV shows after long days of COVID homeschooling, Kingdom of Nauvoo kept me captivated. This review in The New Yorker assures me I wasn’t the only one to find the book compelling.

When I recommend the book to friends and family (wait, you DON’T regularly find yourself casually recommending histories of Nauvoo?), the most frequent question I get is how it compares to Richard Bushman’s Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. The key difference is probably in the framing of the books. Rough Stone Rolling is a biographical and theological history of Joseph Smith that seeks to answer the question of why so many thousands of people found Joseph’s message compelling and gave up everything to join the restoration movement. Kingdom of Nauvoo, however, is primarily a political history that examines power and gender dynamics in Nauvoo in a moment of crisis for a minority religious group within the relatively new American democracy. Park takes the story of Nauvoo outside of its insular Mormon context and into a broader American context.

As a political history, there are two aspects that I found particularly compelling. The first is Park’s analysis of the Council of Fifty, an organization whose minutes were made available to researchers for the first time in 2016. Joseph organized the Council of Fifty in 1844 just a few months before his death as a theocratic body intended to replace what Joseph viewed as America’s failed democratic experiment. The council was to write a new constitution to replace the United States Constitution and provide a forum for God’s voice to rule. Significantly, after Joseph had organized the Relief Society in 1842 and incorporated women into the Quorum of the Anointed in 1843, thereby expanding women’s roles and formal leadership in the city and ecclesiastical structure of the Church, the Council of Fifty was all-male and members were instructed to keep their activities secret from even their wives.

The second aspect is Park’s poignant explanation of Joseph’s legal maneuvering through the Nauvoo City Charter and City Council. The charter granted the city unusual rights regarding issuing writs of habeas corpus, which allowed them to protect Joseph and other leading men from arrest and extradition. This analysis of the unusual use of writs within the city helped me understand why Joseph’s personal and political enemies may have viewed him and the city as a threat to law and order and why some viewed mob action as the only way to achieve justice. Between his explanation of the role of the Council of Fifty and Nauvoo’s atypical use of writs, Park clarified points of political activity that had previously seemed murky for me.

While Joseph remains the central character of the book, Park incorporates women in a way that complicates traditional narratives and grants women greater historical agency than is sometimes seen in histories of Nauvoo. Women such as Sarah M. Kimball, Sarah Pratt, Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and Vilate Kimball aren’t simply tokenized, but are shown to take an active role in social, political, and religious developments in the city. While I have yet to read a book of general Mormon history that I haven’t thought could benefit from more inclusion of women, Kingdom of Nauvoo is a good example of what I hope to see more of: using women’s own words when possible and including them as individuals driving action, not just responding to the actions of leading men.

One criticism of the book has been that Park is too careful regarding polygamy. I don’t necessarily agree. There are much longer books dedicated specifically to polygamy in Nauvoo, and the perceived weakness of not getting into the weeds of many of the details of lived polygamy allows for one of the book’s strength of placing polygamy in the context of Smith’s broader theological and theocratic developments. Park argues that some of the same impulses that drove the polygamy project—a desire to create order and certainty in a chaotic and fallen world—pushed some of Joseph’s most extreme theocratic developments. Neither polygamy nor Joseph’s attempts at theocracy were successful in bringing order to chaos, but rumors of both increased tensions in the city and were directly related to the circumstances that led to Joseph and Hyrum’s arrests and murders in Carthage Jail.

On a personal level, this book will always be tied with my memories of the world shutting down due to COVID. Nevertheless, I don’t hesitate to recommend Kingdom of Nauvoo as an important contribution not only to the history of Nauvoo and early Mormonism, but to the history of American religion and democracy. I was not at all surprised when the Mormon History Association awarded Kingdom of Nauvoo the Best Book award at their 2021 conference. It is a book worth reading.

Benjamin E. Park, author of Kingdom of Nauvoo. Image from his website, https://benjaminepark.com/

Benjamin E. Park, author of Kingdom of Nauvoo. Image from his website, https://benjaminepark.com/Kingdom of Nauvoo releases in paperback this month and is also available in hardcover, ebook, and as an audiobook (if you can excuse the reader’s pronunciation of “Nauvoo,” it is otherwise an excellent narration).

The Book that Shut Down the World – Benjamin E. Park’s Kingdom of Nauvoo

In late February 2020, I joined a couple dozen people for a living room soirée to listen to Benjamin E. Park talk about his new book, Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of A Religious Empire on the American Frontier. Dr. Park, an assistant professor of early American history at Sam Houston State University, situates the mid-19th century city of Nauvoo as an example of the tenuous nature of American democracy for a religious minority on the fringe of American society and geography. How far did freedom of religion extend? Nauvoo tested those limits.

At the event, Park offered an overview of the themes from his book, answered questions, and signed copies. I met several friends I only knew via social media and we chatted over homemade bread with honey butter. While news headlines were becoming more concerning by the day, I certainly did not realize that this would be my last evening out without worrying about masks or social distancing or a devastating global pandemic. Park’s book tour was cut short as university campuses and book stores closed and seemingly the entire world shut down.

It is in this broader context of uncertainty and ramped up anxiety that I first read Kingdom of Nauvoo. And while my personal experience of reading may not be relevant to the content of the book, it highlights to me the brilliance of what Park accomplished. Though it is meticulously researched, the book was published by a national press and is written for a general audience. Clocking in at a slim 279 pages, the book’s narrative moves at a fast clip and remains an interesting and accessible read. At a time when I set aside my own research and writing and mostly sought comfort TV shows after long days of COVID homeschooling, Kingdom of Nauvoo kept me captivated. This review in The New Yorker assured me I wasn’t the only one to find the book compelling.

When I recommend the book to friends and family (wait, you DON’T regularly find yourself casually recommending histories of Nauvoo?), the most frequent question I get is how it compares to Richard Bushman’s Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. The key difference is probably in the framing of the books. Rough Stone Rolling is a biographical and theological history of Joseph Smith that seeks to answer the question of why so many thousands of people found Joseph’s message compelling and gave up everything to join the restoration movement. Kingdom of Nauvoo, however, is primarily a political history that examines power and gender dynamics in Nauvoo in a moment of crisis for a minority religious group within the relatively new American democracy. Park takes the story of Nauvoo outside of its insular Mormon context and into a broader American context.

As a political history, there are two aspects that I found particularly compelling. The first is Park’s analysis of the Council of Fifty, an organization whose minutes were made available to researchers for the first time in 2016. Joseph organized the Council of Fifty in 1844 just a few months before his death as a theocratic body intended to replace what Joseph viewed as America’s failed democratic experiment. The council was to write a new constitution to replace the United States Constitution and provide a forum for God’s voice to rule. Significantly, after Joseph had organized the Relief Society in 1842 and incorporated women into the Quorum of the Anointed in 1843, thereby expanding women’s roles and formal leadership in the city and ecclesiastical structure of the Church, the Council of Fifty was all-male and members were instructed to keep their activities secret from even their wives.

The second aspect is Park’s poignant explanation of Joseph’s legal maneuvering through the Nauvoo City Charter and City Council. The charter granted the city unusual rights regarding issuing writs of habeas corpus, which allowed them to protect Joseph and other leading men from arrest and extradition. This analysis of the unusual use of writs within the city helped me understand why Joseph’s personal and political enemies may have viewed him and the city as a threat to law and order and why some viewed mob action as the only way to achieve justice. Between his explanation of the role of the Council of Fifty and Nauvoo’s atypical use of writs, Park clarified points of political activity that had previously seemed murky for me.

While Joseph remains the central character of the book, Park incorporates women in a way that complicates traditional narratives and grants women greater historical agency than is sometimes seen in histories of Nauvoo. Women such as Sarah M. Kimball, Sarah Pratt, Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and Vilate Kimball aren’t simply tokenized, but are shown to take an active role in social, political, and religious developments in the city. While I have yet to read a book of general Mormon history that I haven’t thought could benefit from more inclusion of women, Kingdom of Nauvoo is a good example of what I hope to see more of: using women’s own words when possible and including them as individuals driving action, not just responding to the actions of leading men.

One criticism of the book has been that Park is too careful regarding polygamy. I don’t necessarily agree. There are much longer books dedicated specifically to polygamy in Nauvoo, and the perceived weakness of not getting into the weeds of many of the details of lived polygamy allows for one of the book’s strength of placing polygamy in the context of Smith’s broader theological and theocratic developments. Park argues that some of the same impulses that drove the polygamy project—a desire to create order and certainty in a chaotic and fallen world—pushed some of Joseph’s most extreme theocratic developments. Neither polygamy nor Joseph’s attempts at theocracy were successful in bringing order to chaos, but rumors of both increased tensions in the city and were directly related to the circumstances that led to Joseph and Hyrum’s arrests and murders in Carthage Jail.

On a personal level, this book will always be tied with my memories of the world shutting down due to COVID. Nevertheless, I don’t hesitate to recommend Kingdom of Nauvoo as an important contribution not only to the history of Nauvoo and early Mormonism, but to the history of American religion and democracy. I was not at all surprised when the Mormon History Association awarded Kingdom of Nauvoo the Best Book award at their 2021 conference. It is a book worth reading.

Benjamin E. Park, author of Kingdom of Nauvoo. Image from his website, https://benjaminepark.com/

Benjamin E. Park, author of Kingdom of Nauvoo. Image from his website, https://benjaminepark.com/Kingdom of Nauvoo releases in paperback this month and is also available in hardcover, ebook, and as an audiobook (if you can excuse the reader’s pronunciation of “Nauvoo,” it is otherwise an excellent narration).

August 9, 2021

Come Follow Me: Doctrine and Covenants 94–97 “For the Salvation of Zion”

In late December of 1832 and early January of 1833, Joseph Smith had a revelation that church members should build a temple in Kirtland, Ohio. This would be the first temple of the newly established church.

Organize yourselves; prepare every needful thing; and establish a house, even a house of prayer, a house of fasting, a house of faith, a house of learning, a house of glory, a house of order, a house of God.

D&C 88:119

However, like many of us who create well-intentioned and ambitious New Year’s resolutions in early January, Joseph Smith and his peers accomplished very little in the months that followed. In June, the Lord reminded Joseph Smith of this unfinished project.

“Building the Kirtland Temple” by Walter Rane

Verily, thus saith the Lord unto you whom I love, and whom I love I also chasten that their sins may be forgiven, for with the chastisement I prepare a way for their deliverance in all things out of temptation, and I have loved you—

Wherefore, ye must needs be chastened and stand rebuked before my face;

For ye have sinned against me a very grievous sin, in that ye have not considered the great commandment in all things, that I have given unto you concerning the building of mine house.

D&C 95:1-3

According to these verses, whom does the Lord chasten?

Why does He chasten them?

How do these insights affect the way we receive chastening or chasten others?

The theme of chastening comes up again in D&C 97, a revelation directed to the Latter-day Saint community in Jackson County, Missouri. The Lord commends Parley P. Pratt for his work leading the School in Zion, a seminary for elders patterned after Joseph Smith’s School of the Prophets in Kirtland, but adds:

And to the residue of the school, I, the Lord, am willing to show mercy; nevertheless, there are those that must needs be chastened, and their works shall be made known.

D&C 97:6

The following verses talk about how we can be accepted of the Lord after we are chastened:

Verily I say unto you, all among them who know their hearts are honest, and are broken, and their spirits contrite, and are willing to observe their covenants by sacrifice—yea, every sacrifice which I, the Lord, shall command—they are accepted of me.

For I, the Lord, will cause them to bring forth as a very fruitful tree which is planted in a goodly land, by a pure stream, that yieldeth much precious fruit.

D&C 97:8-9

According to this verse, how can we be “accepted of” the Lord?

How is seeking acceptance of the Lord different from how we tend to seek acceptance from our peers?

What does it mean to “observe [our] covenants by sacrifice”? How do we do this?

Seeking and receiving the acceptance of the Lord will lead to the knowledge that we are chosen and blessed by Him. We will gain increased confidence that He will lead us and direct us for good. His tender mercies will become evident in our hearts, in our lives, and in our families.

With all my heart I invite you to seek the Lord’s acceptance and enjoy His promised blessings. As we follow the simple pattern the Lord has laid out, we will come to know that we are accepted of Him, regardless of our position, status, or mortal limitations.

—Elder Erich W. Kopischke, Being Accepted of the Lord, 2013

Becoming “Chosen”

After chastening the Kirtland members, the Lord repeated something he had said often during his earthly ministry in Jerusalem.

But behold, verily I say unto you, that there are many who have been ordained among you, whom I have called but few of them are chosen.

D&C 95:5

Jesus explained the concept of “many are called but few are chosen” through parables. Let’s read one of these parables:

The kingdom of heaven is like unto a certain king, which made a marriage for his son,

And sent forth his servants to call them that were bidden to the wedding: and they would not come.

Again, he sent forth other servants, saying, Tell them which are bidden, Behold, I have prepared my dinner: my oxen and my fatlings are killed, and all things are ready: come unto the marriage.

But they made light of it, and went their ways, one to his farm, another to his merchandise:

And the remnant took his servants, and entreated them spitefully, and slew them.

But when the king heard thereof, he was wroth: and he sent forth his armies, and destroyed those murderers, and burned up their city.

Then saith he to his servants, The wedding is ready, but they which were bidden were not worthy.

Go ye therefore into the highways, and as many as ye shall find, bid to the marriage.

So those servants went out into the highways, and gathered together all as many as they found, both bad and good: and the wedding was furnished with guests.

And when the king came in to see the guests, he saw there a man which had not on a wedding garment:

And he saith unto him, Friend, how camest thou in hither not having a wedding garment? And he was speechless.

Then said the king to the servants, Bind him hand and foot, and take him away, and cast him into outer darkness; there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.

For many are called, but few are chosen.

Matthew 22:1-14

Who was “called” in this parable?

Who was “chosen”?

How can we be chosen?

Being called and being chosen are both passive verbs in the English language, so we may picture ourselves passively waiting for someone else to both call us and choose us. But in the parable, wedding guests were chosen because they took the initiative to come when they were called. Through their agency, they chose themselves.

In the story the king sent out his servants to all types of people. It’s the same with our invitation. It doesn’t matter what our starting point is, who we are by nature, what our background is, what talents we do or do not have, what knowledge we have, what our circumstances are. The thing that determines whether or not we are chosen is how we respond to the calling when we sense God’s invitation in our heart, and what fruit we bear as a result.

-Ann Steiner, Active Christianity

In D&C 95:6, the Lord describes those who are not chosen, or in other words, those who chose not to respond to the Lord’s calling, this way:

They who are not chosen have sinned a very grievous sin, in that they are walking in darkness at noon-day.

D&C 95:6

How is ignoring the invitations of the Lord like walking in darkness at noon?

How can we recognize when we are walking in darkness?

How can we find light when we feel like we are in darkness?

Another parable about the “called” and “chosen” offers hope for the Kirtland Saints who had procrastinated their assignment to build a temple, the Missouri elders who needed chastening at school, or for any of us who are late in fulfilling our life callings, repenting of our sins, or living up to our potential:

For the kingdom of heaven is like unto a man that is an householder, which went out early in the morning to hire labourers into his vineyard.

And when he had agreed with the labourers for a penny a day, he sent them into his vineyard.

And he went out about the third hour, and saw others standing idle in the marketplace,

And said unto them; Go ye also into the vineyard, and whatsoever is right I will give you. And they went their way.

Again he went out about the sixth and ninth hour, and did likewise.

And about the eleventh hour he went out, and found others standing idle, and saith unto them, Why stand ye here all the day idle?

They say unto him, Because no man hath hired us. He saith unto them, Go ye also into the vineyard; and whatsoever is right, that shall ye receive.

So when even was come, the lord of the vineyard saith unto his steward, Call the labourers, and give them their hire, beginning from the last unto the first.

And when they came that were hired about the eleventh hour, they received every man a penny.

But when the first came, they supposed that they should have received more; and they likewise received every man a penny.

And when they had received it, they murmured against the goodman of the house,

Saying, These last have wrought but one hour, and thou hast made them equal unto us, which have borne the burden and heat of the day.

But he answered one of them, and said, Friend, I do thee no wrong: didst not thou agree with me for a penny?

Take that thine is, and go thy way: I will give unto this last, even as unto thee.

Is it not lawful for me to do what I will with mine own? Is thine eye evil, because I am good?

So the last shall be first, and the first last: for many be called, but few chosen.

Matthew 20:1-16

Why did all of the laborers receive equal wages, although some had arrived earlier than others?

In what ways do we sometimes display the same logic as the earliest laborers, who became unsatisfied with their pay only after they saw that others were paid just as much?

How can we alter this pattern of thinking and develop more Christ-like attitudes?

General Primary President Rosemary M. Wixom taught these strategies for adjusting our attitudes and seeking acceptance from the Lord:

Looking out through a window, not just into a mirror, allows us to see ourselves as His. We naturally turn to Him in prayer, and we are eager to read His words and to do His will. We are able to take our validation vertically from Him, not horizontally from the world around us or from those on Facebook or Instagram.

—President Rosemary M. Wixom, Discovering the Divinity Within, 2015

What does it mean to look “out through a window” instead of “into a mirror”?

To take validation “vertically” instead of “horizontally”?

How can we apply this counsel in our lives?

August 2, 2021

To Be Lawful or Good

In Dungeons and Dragons, the characters in the game can have one of nine different alignments that indicate the character’s orientation toward law vs chaos on one axis and good vs evil on the other axis. Each axis has three points – good, neutral, evil on the good/evil axis and lawful, neutral, chaotic on the law vs chaos axis. So a character can be, for example, lawful good (one who obeys systems of authority and does the morally correct thing), chaotic evil (one who rejects systems of authority and does the morally wrong thing), neutral evil (one who doesn’t care one way or the other about systems of authority and does the morally wrong thing), etc.

There’s an interesting dilemma that can occur for a lawful good character when what is lawful and what is good conflict. Does one obey the law, thus violating the moral code, or does one do the morally correct thing, thus violating the law?

chart

chartIn LDS theology, I think a case can be made for viewing God as lawful good. As people who are supposed to aspire to be like God, I think we’re supposed to aspire to being lawful good, too. But we live in a fallen world where what is lawful and what is good sometimes conflict.

The two alignments that are closest to lawful good but take different answers to the dilemma are lawful neutral (obey systems of authority without regard to what is morally correct) or neutral good (without regard to systems of authority, do the morally correct thing).

I think the church teaches that lawful neutral is superior to neutral good. We can see this with the Mormon interpretation of Eve in the Garden of Eden (she did the right thing by eating the fruit, but she broke the law to do so, and she was punished with painful childbirth and subjection to Adam as a result – her punishment shows that lawful is more important than good). We can also see this in the story of Abraham (he was told to kill his son – a wrong act – but the command came from an angel, so it was a lawful act. He was praised for his willingness to perform the act, showing that lawful is more important than good).

Jesus was neutral good, however. When He viewed the actions of the Pharisees (the lawful leaders) as morally wrong, He defied them in favor of doing what was right.

In addition to being what I see as a morally wimpy stand, I think prioritizing following authority over doing the right thing gets straight at the heart of the conflict at the center of the war in heaven. Satan’s plan was for everyone to follow authority all the time without thinking or choosing. I think he was lawful neutral at the beginning. But if we want to be like Jesus, I think we need to be neutral good.

There isn’t really a place to say that at church, though. I remember once in an institute class when we were discussing the 12th article of faith I raised the issue of how to decide when to disobey morally repugnant laws, and everyone was shocked that I would even contemplate the idea that breaking the law was ever okay. Like, until that point, I thought it was universally accepted that sometimes breaking the law is necessary. (The extreme example is in WWII Europe, I thought everyone today would view hiding Jews in the basement as the morally proper thing to do even if it was against the law.)

I wonder what it would take to make a large swath of church members reevaluate their views on law vs goodness.

August 1, 2021

The Power of Stories: Interview with Heather Sundahl

“I will tell you something about stories…they aren’t just for entertainment. Don’t be fooled. They are all we have, you see, all we have to fight off illness or death. You don’t have anything if you don’t have stories.”–Leslie Marmon Silko

“I will tell you something about stories…they aren’t just for entertainment. Don’t be fooled. They are all we have, you see, all we have to fight off illness or death. You don’t have anything if you don’t have stories.”–Leslie Marmon Silko

All our lives we are surrounded by stories: nursery rhymes and fairy tales, scripture and literature, gossip and family history. How do these stories shape and define us? Can changing a story change a life? I believe that it can. Think about what stories you most often tell about yourself, your family, your faith. What do those stories reveal? What messages are sent? Are there aspects of those stories that don’t work for you anymore? I believe as we seek out divinity–and the divine in ourselves–we will find the power to rethink and reclaim our stories. It is how we interpret the events of our lives, and not the events themselves, that determine our happiness.

In June, I was interviewed by Kyrie Papenfuss about my decades long research on the power of stories. In her , Kyrie addresses a wide range of topics in her interviews: being Asian-American, Healthy Sexuality, Understanding OCD, being Miss Utah, and more. Kyrie describes her podcast as “a discussion on secular topics through a gospel lens. In 3 Nephi 16:3, Christ says, ‘they shall hear my voice and shall be numbered among my sheep, that there may be one fold and one shepherd.’ Our podcast’s goal is to increase unity and understanding as we strive to be ‘One Fold.'”

If you want to explore how the way we frame out stories shapes our lives, give it a listen!

July 28, 2021

Titles of Inequality

Guest post by Green.

The church has a long history of members referring to each other as “brother” or “sister.” In the early days of the church, the prophet was known as “Brother Joseph (one example from the Joseph Smith papers is here). I kind of like this idea; it makes the church seem a familial place, focused on families and inclusion. But I think this title history is more complex.

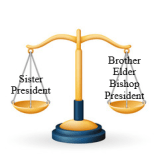

There are quite a few blog posts online discussing the concept behind “Bother” and Sister” titles, much the rhetoric is focused in a very good way- teaching that we are all children of God, and need to look out for each other as we would in a family. In 2018, LDSLiving posted a piece on the “brother and sister” title ideology, claiming that it “It Reminds Us We Are All Equal.”

As God’s children, we are all equal because ” all are alike unto God” (2 Nephi 26:33). Using “brother” and “sister” reminds us of this. We may have different callings like Relief Society president, bishop, Primary president, stake president, etc., but this doesn’t mean we are better than each other. Because we all carry the title “brother” and “sister,” we don’t set anyone higher than the other. No job position, marital status, or amount of wealth sets us apart because when we walk through the chapel doors, we are all “brother” and “sister” and we are all trying to live the gospel.

Except that last part is not true. For example, when is the last time you called your bishop, “brother”? Over the past decade I have even heard of bishops and branch presidents referring to female primary and relief society presidents as “President Smith,” as a means of showing respect to their position—possibly in reaction to the Ordain Women movement.

Except that last part is not true. For example, when is the last time you called your bishop, “brother”? Over the past decade I have even heard of bishops and branch presidents referring to female primary and relief society presidents as “President Smith,” as a means of showing respect to their position—possibly in reaction to the Ordain Women movement.

A BYU devotional titled “Brotherly Love” wherein two-gendered titles are revered only is laughably ironic, and the church’s own website includes a piece arguing that referring to each other as “brother” or “sister” “help(s) us best relate to each other?.” This particular piece also includes the stipulation that “the titles Bishop and President are appropriate even after the (male) leader has been released.” So, uh… they aren’t a part of that big holy family with the rest of us, but rather a part of a class of folks that are deserving of bigger titles. *sigh*

Simply put, we are NOT equal in the church. Even when we use titles that we pretend are equal. Calling me a “sister” to another person’s “brother” only serves as a reminder that my position in the church is lower because of my gender, which is highlighted by the “sister” church title. Why else are male missionaries called “Elder” to the title of “sister” for female missionaries?

“Sisters” cannot raise to the title of elder or bishop, whereas a “brother” may do so. Thus the title of brother is inherently more powerful than the title of sister. Men will always have greater authority and power than women so long as we continue to use the term “presiding,” and we ban women from holding “priesthood keys.” We are constantly reminded of our lower position in the church by use of these gendered titles.

I have found that calling each other by these titles is further problematic because of the confusion it brings to those outside of the church. Years ago, when I was in the Hill Cumorah Pageant, non-members were known to ask where I had trained to obtain the title of sister, as displayed on my name badge. “Did you obtain that title at BYU?” they would ask. It became a much more common discussion topic than the intended missionary work.

In addition to the divisive sexism these gendered titles enforce, in the age of LGBTQIA+,

these titles are discriminatory. As a diagnostically intersex individual, I feel for my LGBTQIA+ community. Though I identify as female, I feel for those who have XX chromosomes and testicles. I ache for those who have XXY chromosomes, beards and breasts, and mostly for those who chose to not identify with a specific gender. Are these people not our eternal siblings as well?

I suggest that we retire these sexist, gendered, discriminatory titles as call each other ‘Saints’. After all, this is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. ‘Saints’ to me is much more inclusive

and reflective of the mission of the church to be of service and love to all. It reflects my mind and heart, and not my body. It gives me a matching title to my spouse, and reminds us that we are truly equal because we have the same label.

It is a baby step. But it is an important baby step.

July 27, 2021

Guest Post: Sister, Thou Wilt Surely Wear Away

Guest Post by Nicole. Nicole is an adult convert, a non-Black woman of color, and a professional diplomat. She blogs at nandm.sbitani.com and writes microfiction @nsbitani on Twitter. The content of this post does not represent the views of the U.S. Department of State or any other U.S. Government agency, department, or entity. The thoughts and opinions expressed here are solely those of the author and in no way should be associated with the U.S. Government.

One of the interesting things about being an adult convert, a woman, and the only member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in my family is that I rarely know what’s going on in Elders Quorum. Even still, I sometimes find myself witness to an institutional-scale version of the conversation countless heterosexual couples notoriously have in their home over division of labor and mental load. I don’t even need a Priesthood holder in the home to know that there are unnecessary inequities in church that cannot be found in any Scripture or Handbook.

Specifically, I’ve concluded that outside of clearly defined responsibilities for Elders Quorum and Relief Society there are many additional things that Relief Society takes on – often unconsciously. No wonder so many faithful women are burned out and overwhelmed from Relief Society’s formal callings and informal demands on their time, energy, attention, and work!

One example of this I’ve seen in almost every place I’ve lived is signing up to feed the locally assigned full-time missionaries. In person, well-meaning leaders often circulate sign-up sheets during Relief Society, depriving entire households without women in Relief Society the opportunity to benefit from the missionaries joining them for a meal at home. As we’ve been meeting over Zoom during the pandemic, this Relief Society-exclusive call for missionary meals shifted online. Even as the COVID-19 mitigation restrictions in our country prohibited almost every family in my ward from hosting the missionaries in person and we switched to coordinating takeout deliveries, everyone looked to the women to fulfill the need. I can assure you with great confidence: our brothers are at least as adept at ordering a pizza as our sisters. So why do we remind only sisters to sign up in Sunday meetings, Facebook posts, and periodic emails? Why are the sisters expected to place food orders every time a new cohort of missionaries enters into mandatory quarantine? Many sisters relish these opportunities to serve, but we are depriving worthy men of that same chance to follow the Savior’s example (Luke 22:27) and serve our fellow beings and God (Mosiah 2:17).

Missionary meals is just one example of a phenomenon I’ve seen and heard over and over again. Sometimes, Relief Society takes on work that could be shared with other organizations like Elders Quorum. Other times, sisters feel pressured to live up to unrealistic expectations in their callings or are unfairly compared to others who spent hours on details like party invitations that–though lovely–are not core principles of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. I have never heard a brother express exhaustion at criticism over the graphic design of an Elders Quorum activity’s branding.

I’m not saying that Relief Society should become just like Elders Quorum, because I don’t think it should. But I do believe we as sisters and leaders should think more carefully about the additional labor we take on in Relief Society and ask ourselves a few key questions before accepting more:

How does this additional labor or responsibility make me feel? Do I feel like my local leadership respects my time and effort? What answers do I receive when I pray about this assignment?How much additional time will this add to my calling and other sisters’ callings?Is there a reason this responsibility or volunteer opportunity should fall under the Relief Society alone and not the Elders Quorum or ward as a whole?Is this an opportunity where not just the Relief Society but youth or all adults could help?Will this additional work cause other, more essential work such as ministering to suffer?Am I creating an unrealistic expectation for the next sister who will do this calling or volunteer opportunity?If we prayerfully consider the above, I am certain we can sanctify and amplify our callings and participation in Relief Society without overwhelming ourselves and other sisters. We should heed the wise words of Jethro to his son-in-law Moses: “The thing that thou doest is not good. Thou wilt surely wear away, both thou, and this people that is with thee: for this thing is too heavy for thee; thou art not able to perform it thyself alone” (Exodus 18:17-18). Sisters: if this thing is too heavy for you, you are not alone. And we don’t have to perform it ourselves alone anymore.

July 26, 2021

Thoughts on Sister Emma.

Emma Smith, by Cassandra Barney

Some thoughts on our founding sister and woman – Emma.

I am grateful she has been a part of lessons and talks and discussions from childhood on. And that what I have heard and studied and sought reveals a complex, complicated woman. I realize what I learn of Emma can’t help but impact what I seek and consider about the divine feminine, Goddess, Mother God, Eternal sister. I appreciated teachers who spoke with admiration for this woman who was older, more educated and more wise than Joseph Smith. She probably loved him early, and so much that she was willing to step into an unknown, and possibly lone and dreary world of partnering with someone so immersed in mystical and extraordinary thoughts and actions. I wonder how much she felt her own ability to influence him. I don’t think we would have such an essential and unusual doctrine about Heavenly Mother, Goddess co-creator, the council of Gods which included all of us, or teachings that complex partnership is essential in developing the qualities of godhood, if not for Emma. What were the conversations like between Emma and Joseph? What questions did she herself take to her own sacred grove? What visions did she have, and share with him? Did she trust that he would recognize the value of her contribution as much as his own? Did she see the need to contribute her own voice through the translation and revelation he could provide, since he was a man in a patriarchal society? In those days when she was his scribe for revealing the tragic Book of Mormon story of a family trying to find their way to God while wrestling with their relationships with each other, did she contribute her own seeing in the seer process – her own awareness of the women and the inexcusable violence and the unwillingness of Nephi’s parents to excuse Laban’s murder (their reaction is glaringly absent from Nephi’s narrative, and I can just imagine Nephi’s mother saying “Oh, no, Nephi, you will not throw God under the bus for this”). Were there more women’s names and voices in the pages she wrote? If she had continued to be his scribe, would there have been more clear condemnation of violence, and more embracing of the transformative power of mercy? Would the burying of weapons be more praised than the banner demanding liberty at all costs? I wonder.

But those messages are there. And we still deal with the heavily patriarchal interpretations that dismiss what I imagine Emma would have elevated. She is a complex woman who spread her influence in a society that would defy and diminish her. For me, I imagine she is essential in the conversations that had Joseph extending keys to women, that created ritual which taught no one is complete without the opposite, that we can only exist as part of one great whole, that the universal salvation message of the gospel and the power of Gods to inspire and transform us all is both terrifying and glorious and it takes courage to proclaim and live it – even at the cost of lives. I see evidence that Joseph was wondering about some of this, but it is clear that her presence and influence carried his seeking and willingness to receive further light and knowledge into expansive realms.

I mourn the schism created in the restoration family after Joseph died, when Brigham was so unwilling to see how Emma was such a crucial part of the work, when Brigham seemed to assign blame for Joseph’s death on those who spoke up when Joseph was not being who he promised he would be. It is a rift that has come close to destroying the most inspiring messages revealed in the restoration gospel.

I can’t help but wonder how things would have been different if Brigham had followed one of the most compelling revelations we have in section 121, and practiced the compassionate, merciful qualities of God, creating a council that included Emma and other women, to create the kingdom after the patterns of universal inclusion. It is interesting to imagine an alternate history. A history that does not include the priesthood ban, or section 132, or any abusive polygamy practice and rhetoric, or weaponized proclamations, and deadly policies. It does not include the spiritual violence of excommunication because of disagreement. The rites, gifts, power and blessings of women would be expanded and celebrated, not denied and punished.

I am not so blind as to suggest all struggles and problems would be eliminated in this more inclusive history. We are all still human, and would still tend to look for ways and reasons to deny connection, to build barriers, to “other” anyone who we think is different, and to blame the other. But I can’t help imagine – what if? What if all were included, all voices heard, all existence worthy and valid, because the voice of a strong, creative woman was seen as essential in creating a future after the unthinkable happened, and Joseph was gone. I want that to be so, if not then, now.

Emma is an example of one who created a new future, even when her world seemed to have been completely destroyed. This first woman inspired many branches of the restoration family. My hope is that we learn from the story which Emma was the first to write – the tragic story of Lehi and Sariah’s family, who chose to destroy each other rather than practice the radical inclusion and forgiveness and love taught by Christ.

I am spiritually descended from Emma through the Brighamite line, yet I continue to feel most inspired to recall and to practice expanding on what began before the migration. When I visit my ancestor’s graves, or family sites, I sing from the hymns Emma compiled, the hymns they would have sung. I read their journal accounts of wondering where to go, and following inspiration, not from Brigham, but from God, who sometimes spoke in a woman’s voice. And when I read accounts of foremothers who threw coffee in Brighams’ face, defying his demands and following their own divine inspiration, I realize that much of what I think Emma brought to the early years of the restoration is a part of my line, no matter how many plains were crossed, or how many voices are excluded from councils. Emma was one who sought and spoke and wrote and stood. She is an example of creating the presence of the goddess even when no one seemed ready or willing to see it. I am deeply grateful she is my spiritual foremother. She leads me to continue seeking more, and more, letting go of someone else’s idea of a quiet, submissive, invisible, physically pleasing but silent mother, but rather embracing a complex, fierce, earthy, firey, fluid, inspiring, incomprehensibly expansive woman – mother – sister who challenges and calls me into transformative being, creating a new future every day.

July 25, 2021

Sacred Music Sunday: Come, Come, Ye Saints

I was never a big fan of the hymn Come, Come, Ye Saints. As a matter of musicality, I found it trite and sappy. However, when I was looking for a seasonally appropriate hymn for today’s installment, it came up as the logical choice.

The music still doesn’t do much for me, but I like the message. As the pioneers were walking across the plains fleeing persecution, they were suffering great hardship. They lost their homes, their belongings, their loved ones. Some of them even lost their lives. But they sang the refrain “all is well”.

Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsI’m a relentless optimist, but the past year and a half it has been difficult to maintain that optimism. So often, when we’re in the midst of trials and challenges, it’s easy to say that things will be better in some indeterminate future – after the trial is over, or even in the afterlife. But things can be better now. God is with us in the thick of things while our challenges are ongoing.

[I]n all these things we are more than conquerors through him that loved us. For I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.Romans 8:37-39

And if nothing can separate us from the love of God, then come what may, all is well.

July 23, 2021

Better styles and fabrics aren’t enough. Let’s end the garment-wearing mandate.

The New York Times recently featured an article about Mormon women’s garments, featuring interviews with brave and smart Latter-day Saint women. If you haven’t read it yet, you should.

But the New York Times got one thing wrong; it described the requirement for most adult members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) to wear garments as an “exhortation.” The garment wearing rule is actually a strictly enforced mandate, with frequent compliance checks and devastating consequences for people who disobey.

Beginning with her first time attending the LDS temple endowment ceremony, each Latter-day Saint woman (and man) must meet one-on-one with a male (never female) interviewer at least once every other year. The male interviewer reads a 2-paragraph statement about garment-wearing rules and asks the woman if she is in compliance. (You heard that right, a male church leader asks each adult woman in his congregation, one by one, what underwear she wears.) If she skips the interview or admits that she is not in compliance, she is denied access to LDS temples. She may not participate in sacred rites that are deemed necessary for salvation within Mormon theology. She is banned from the temple weddings of her friends and family.

Beginning with her first time attending the LDS temple endowment ceremony, each Latter-day Saint woman (and man) must meet one-on-one with a male (never female) interviewer at least once every other year. The male interviewer reads a 2-paragraph statement about garment-wearing rules and asks the woman if she is in compliance. (You heard that right, a male church leader asks each adult woman in his congregation, one by one, what underwear she wears.) If she skips the interview or admits that she is not in compliance, she is denied access to LDS temples. She may not participate in sacred rites that are deemed necessary for salvation within Mormon theology. She is banned from the temple weddings of her friends and family.

To the 600+ New York Times commenters who are wondering why Mormon women would wear garments day and night even if the practice is too unhealthy and uncomfortable to feel spiritually enriching: that’s why.

Many of the women interviewed by the New York Times are advocating better garment styles and fabrics. I’ve done that myself many times, such as here and here and here.

Church officials have been responsive. Many of the garment changes advocated by me and other Latter-day Saint women have been implemented. The woman’s garment of today is a thousand times better then what they made our grandmothers wear.

And yet, it is still terrible.

I don’t believe that the brethren who lead our church want women to endure garment-induced urinary tract infections, yeast infections, heat strokes and hot flashes; or that they want pregnancy, lactation and menopause to be even more uncomfortable for women than they already are naturally; or that they like the idea of women bleeding all over their garments when they menstruate. It’s not that male church leaders don’t care about female comfort and hygiene, it’s just that church officials have other priorities for the garment that they care about more. It’s more important to the brethren that the garment cover a woman’s legs than that a women can attach a menstrual pad to her underwear. If making great women’s underwear was actually the primary goal of Church garment designers, Latter-day Saint women wouldn’t still be coping with underpants that cannot accommodate a winged menstrual pad more than half a century after the menstrual belt disappeared from the market.

Garments will never be great women’s underwear.

The 24/7 garment-wearing mandate began at a time when long underwear was in fashion and church members were gathering together to live in a low-humidity location. As talented and well-intended as Church garment designers are, they will never find a style or fabric that works for every person in every climate across the world to wear every day and every night in any weather under every appropriate outerwear on every body with every health condition. They certainly can’t pull it off while adhering to the modesty preferences of church officials.

So here is what I propose: let’s stop requiring women (and men) to wear garments as daily underwear.

In 2019, the LDS Church made some steps in the right direction. They eliminated the phrase “wear the garment day and night” from the temple interview and a rule about wearing garments even while doing activities like yard work. That wording was particularly overreaching. (You have to wear our mandated long underwear even when you are alone on your own property doing messy chores in the hot sun! You have to wear it even when you are asleep in your own bed!)

Let’s take it a step further. Let’s cut the question from the interview altogether. Let church members decide for themselves when and where they will wear the garment, without threat of punishment. Those who find it spiritually enriching to wear the garment as underwear all day every day may continue to do so. Others may find it more conducive to their health, climate or culture to only wear the garment at church or the temple. Let them be.

Among Mormon Women, Frank Talk About Sacred Underclothes

Frustrated by itchy, constrictive church-designed garments, they are asking for better fit, more options and “buttery soft fabric.”

Ruth Graham, New York Times, July 21, 2021