Exponent II's Blog, page 123

January 23, 2022

Sacred Music Sunday: The Lord Is My Light

January and February are hard for me. I live in the northern hemisphere, and I’m extremely solar powered. By the time January hits, I’m just done. It’s been dark for months, and the gentle happy glow of Christmas is over. I’m tired, sluggish, cold, unmotivated, and in physical pain. Even high doses of injected vitamin D prescribed by my doctor only barely take the edge off. I just have to push through until March when the sun comes back and my body forgives me for subjecting it to winter.

Descriptions of Jesus as the light of the world resonate with me for this reason. Just as the sun illuminates the darkness and gives me hope and joy and relieves my physical pain, the Son of God illuminates the spiritual darkness and gives me hope and joy and relieves my metaphysical pain.

And when I’m feeling spiritually down, I can remind myself that the Son might be harder to see at some times, but March is coming. The Lord is my light.

January 22, 2022

Guest Post: Eve Creation

Guest Post by Tina. Tina enjoys nature, art, and reading. She is nearly complete with a graduate degree in trauma informed teaching and loves asking questions to learn more about the world.

One January a few years ago I listened in horror as the sacrament meeting speaker, while relating the story of his grandpa’s life, repeatedly stated that his grandma gave up everything important to her to support her husband in his career. This speaker seemed to have internalized the idea that women exist to support men. That the speaker was a 14-year-old boy gave me pause to soberly consider how this boy will treat girls and women as he grows to adulthood.

Where does the view of women existing primarily to support men originate? I suggest that we look at our interpretation of the Eve and Adam creation story. Christianity typically interprets Genesis 2 as Adam being created, God declaring that it is not good for Adam to be alone, and then taking one of Adam’s ribs to form Eve. For hundreds if not thousands of years, this interpretation has been used to support male headship, male priesthood, and female secondary status. After all, in this telling, Adam is the main character and Eve is derivative of and subordinate to a man.

This interpretation and assignment of my worth and status as a female permeated my experience and psyche as I grew up in the church. The effects of this interpretation continued well into adulthood. “Are women fully human who exist independently of men?” An answer of ‘no’ supports the paradigm that women exist to support men. It is this answer that justifies thousands of years of female subjugation.

The answer to this question has long been, and still is, debated by men. It is the question underlying the paradigms of how women and men relate to each other in society and especially in the church. It is the question underlying all other questions: Can women vote? Can women do certain jobs? Can women go to college? Can women serve on juries? Can women work if they are pregnant? Can women have bank accounts in their own names? Does a woman’s body fully belong to her or is she an object called walking pornography or a barn that must be painted before a man is willing to buy, excuse me, marry her? Do her life choices fully belong to her or must she be continually reminded that the choice has been made and that there is one acceptable path of wife and mother? Is a woman human enough to pass out towels, witness a baptism, hold her own baby while they are blessed, pass sacrament trays to a congregation, pray in General Conference, or hold an office in the priesthood of God, Elohim, who consists of both the Eternal Father and the Eternal Mother?

Is any person who is a ‘she’ fully human?

Yes! I mean, I think so. Except for all those times when I am told by my parents, the church and sometimes society, implicitly or bluntly, that I am deformed male; not quite human. Over the years as I tried to hold my ground and stand in my truth, a quiet little voice sometimes wondered if what they said could be true. And so I spent years stunting my development by squeezing my thoughts, choices, and physical body into a box of parental, church, and societal female acceptability. Eventually the slowly simmering heat from the pressure squeezing me inside the box reached a point where I burst into a flame. My mental health in tatters, the flame reduced my psyche to ashes over the following months.

Shattered into nothingness, I cried out for help. Wrapped in comfort by the Divine Feminine, I have spent the last several years rising from the ashes like a brilliant Phoenix infused with new life. I now intend to encourage others by sharing that it is possible to heal from woundedness.

Reexamining our collective and personal interpretations of Eve’s creation is a foundational place to begin healing because the interpretation of that story is where the woundedness originates. We have only a portion of the creation account. This story was passed along orally during a time when there is evidence that partnership societies existed. By the time this account was written, however, the dominance of men over women in the structure known as patriarchy was well established. The story, which likely changed over time, was recorded under the paradigm that viewed women as secondary. It is this view that persists today. And yet, I do not see how the current prevailing interpretation regarding Eve’s creation is supported by the fragment of the story we do have. In Genesis 1, both female and male are created at the same time by God. In Genesis 2, the ‘adam’ is not designated either male or female; ‘adam’ in Hebrew means human. Some scholars and theologians believe that this first human was andrognynous. From this perspective, the female was not taken from a man’s rib (side is a more accurate translation) but that this andrognynous human was divided from its side into two individuals.

We all have both female/male, yin/yang energy within us. To become more fully developed, we nurture these energies inside ourselves, our families, churches, and communities to full expression and balance. Eve was not created because Adam needed an accessory. At the same time, it is true that we need each other. However, women must be recognized as individuals fully human in their own right. Some men, especially in the church, are uncomfortable hearing the painful experiences of women; it seems to offend or scare them. If men have been told they are special for being men but now women are special too, where does that leave them? Perhaps they do not yet know that they are fully human too.

It is time to return to partnership where all people are fully human and have opportunities to grow. For too long we have been frozen in a place of valuing only the masculine. Awareness of the Divine Feminine is waking up in many people. It reminds me of the part in The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe where the inhabitants of Narnia see the snow melting and the Beaver says:

“Aslan is on the move- perhaps has already landed.” And now a very curious thing happened. None of the children knew who Aslan was any more than you do; but the moment the Beaver had spoken these words everyone felt quite different.”

I see the snow melting; I see stirrings for humanity to move forward and I can not help but say that She is on the move. Perhaps She has already landed.

January 21, 2022

Guest Post: One Mom, Two Coming-Out Stories , Part Three

Guest Post by Anonymoys. Anonymous is a wife and mom who lives in an area with a high percentage of LDS people. She enjoys cooking, crafting, and gardening.

When I first began to distance myself from the church, I was motivated in large part by anxiety over my oldest child. I believed there was a good chance they were gay, and I worried for their future in a church where gay people are taught that is wrong to seek to make a commitment to someone you love and feel attraction for. I could not reconcile that counsel with a loving Heavenly Father who wants His children to be happy. I remember thinking many times that my youngest child would probably do just fine in the church, but my oldest would almost certainly face heartache and some extremely tough choices in attempting to reconcile their religious beliefs with the normal human desire to companionship. I felt that to continue to raise my children in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints would mean clipping my oldest child’s wings. And I simply could not do that. I am profoundly grateful that my husband understood this. While he remains an active latter-day saint, he agreed that we could respect our oldest child’s agency enough that we would not force church attendance past the age of ten. We both knew that, for the sake of fairness, we would also have to allow our youngest child the same leeway.

I never could have guessed that, in taking steps to protect my oldest child from potential religious harm, I was, in fact, protecting my youngest child just as much.

Two kids. Two coming-out stories. One nonbinary. One gay. I don’t know what the future holds for my kids. But I do know that they have parents who love them and support them and who want them to have joy and fulfillment in whatever paths they choose.

Growing up in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, I was taught from an early age to prepare for motherhood. I was taught that being a mother was my divine destiny. The greatest desire of my heart was to be a mother. There is no way I could have known that one of the most important ways for me to fulfill my role as a mother would be to create a safe place for a nonbinary child and a gay child to thrive. And the surest way for me to do that would be to provide a path for them to leave the very church that taught me the importance and value of motherhood in the first place.

January 20, 2022

Come Follow Me: Genesis 6–11; Moses 8 “Noah Found Grace in the Eyes of the Lord”

I love the first word of the Come Follow Me manual for this lesson: stories. This lesson covers two of the most beloved and oft-repeated stories in the Old Testament: the story of Noah’s Ark and the story of the Tower of Babel.

The manual begins:

Stories in the scriptures can often teach us multiple spiritual lessons. As you read about the Great Flood and the Tower of Babel, seek inspiration about how these accounts apply to you.

—Come Follow Me for Individuals and Families: Old Testament 2022: Genesis 6–11; Moses 8

Notice some keywords in these instructions. There are multiple lessons to be learned from these stories; they can be interpreted in more than one way. These lessons are intended to be spiritual and inspiring (as opposed to literal, historically accurate or scientific). These stories will apply to unique people differently; everyone can be inspired by them in their own way. Notice the word stories. The authors of the Come Follow Me manual point out that Old Testament stories are different from histories.

Don’t expect the Old Testament to present a thorough and precise history of humankind. That’s not what the original authors and compilers were trying to create. Their larger concern was to teach something about God—about His plan for His children, about what it means to be His covenant people, and about how to find redemption when we don’t live up to our covenants.

—Come Follow Me for Individuals and Families: Old Testament 2022: Reading the Old Testament

What is different about a story from other kinds of writings, like history books?

How should our approach be different when we study scripture stories versus other kinds of texts?

Dr. Carol L. Meyers discusses storytelling in the Old Testament in more detail:

The way people in biblical antiquity accounted for their past is not the same as it is in the modern world. Nowadays we expect “history” to provide an accurate narrative of real events, though we still realize that any two eyewitness observers of an event will recall it in different ways, depending on their individual interests and prior beliefs. But this is a relatively new approach, one that was not present when biblical narratives took shape.

Like other ancient storytellers, the shapers of biblical narratives were not concerned with getting it factually right; rather, their aim was to make an important point. Their narratives could serve many different purposes, all relevant to their own time periods and the audiences they were addressing. They might take a popular legend and embellish it further—the better the story, the more likely that people would listen and learn. They used a variety of sources plus their own creative imaginations to shape their stories.

…Does this understanding of the historicity of biblical texts mean that they are devoid of any validity? Absolutely not. Authentic experiences and events surely underlie many biblical narratives. Archaeology may call the historicity of some texts into question, but it can also indicate the general veracity of others.

…The larger strokes of Israelite history may thereby come into view, but it is likely that relatively few of the narratives can ever be considered history “as it actually happened.” Perhaps the best way to approach the Bible in relation to history is to stop asking whether or not it is true and rather to consider what truths its stories tell.

—Dr. Carol L. Meyers, Professor Emerita of Religious Studies, Duke University

How does it change our perspective if we focus on the truths the stories tell us?

These stories come from a different culture and some of their violent content can be disturbing to modern tastes. (I dare say that if ancient people could watch some of our modern movies, they would also be disturbed by the violence of our modern entertainment.)

Rev. Dawn Hyde describes a common reaction she hears to the story of Noah’s ark, in which God kills nearly every person on Earth, with the exception of one family:

Most people view God here as evil. “This can’t be the God I believe in, the God I know in Jesus Christ….” and so we discount this God as the God of the Old Testament. “Not my God.”

—Rev. Dawn Hyde, September 8, 2015, Noah’s Ark

The authors of the Come Follow Me manual acknowledge this discomfort:

When you consider your opportunity to study the Old Testament this year, how do you feel? Eager? Uncertain? Afraid? All of those emotions are understandable. The Old Testament is one of the oldest collections of writings in the world, and that can make it both exciting and intimidating. These writings come from an ancient culture that can seem foreign and sometimes strange or even uncomfortable. And yet in these writings we see people having experiences that seem familiar, and we recognize gospel themes that witness of the divinity of Jesus Christ and His gospel.

—Come Follow Me for Individuals and Families: Old Testament 2022: Reading the Old Testament

How can we sift through cultural content that may be disturbing to us to find spiritual insights?

How can we distinguish between cultural baggage in scripture and the word of God?

Noah’s Ark

Noah’s Ark on the Mount Ararat, Simon de Myle

Invite class members to read these verses from Genesis 6-9, or to simply describe the Noah’s ark story as they remember it. As you read or talk about the story, consider these questions:

Why might ancient peoples have chosen to pass down this story?

What truths can we learn from this story that apply to our modern world?

How does the story inspire you? How would you apply its truths to your own life?

And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.

And it repented the Lord that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at his heart.

And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth; both man, and beast, and the creeping thing, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made them.

But Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord.

—Genesis 6:5-8

And God said unto Noah, The end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them; and, behold, I will destroy them with the earth.

Make thee an ark of gopher wood; brooms shalt thou make in the ark, and shalt pitch it within and without with pitch.

—Genesis 6:13-14

And, behold, I, even I, do bring a flood of waters upon the earth, to destroy all flesh, wherein is the breath of life, from under heaven; and every thing that is in the earth shall die.

But with thee will I establish my covenant; and thou shalt come into the ark, thou, and thy sons, and thy wife, and thy sons’ wives with thee.

And of every living thing of all flesh, two of every sort shalt thou bring into the ark, to keep them alive with thee; they shall be male and female.

Of fowls after their kind, and of cattle after their kind, of every creeping thing of the earth after his kind, two of every sort shall come unto thee, to keep them alive.

—Genesis 6:17-20

And the flood was forty days upon the earth; and the waters increased, and bare up the ark, and it was lift up above the earth.

—Genesis 7:17

And all flesh died that moved upon the earth, both of fowl, and of cattle, and of beast, and of every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth, and every man.

—Genesis 7:21

And God remembered Noah, and every living thing, and all the cattle that was with him in the ark: and God made a wind to pass over the earth, and the waters assuaged.

—Genesis 8:1

And God spake unto Noah, saying,

Go forth of the ark, thou, and thy wife, and thy sons, and thy sons’ wives with thee.

Bring forth with thee every living thing that is with thee, of all flesh, both of fowl, and of cattle, and of every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth; that they may breed abundantly in the earth, and be fruitful, and multiply upon the earth.

—Genesis 8:15-17

And Noah builded an altar unto the Lord; and took of every clean beast, and of every clean fowl, and offered burnt offerings on the altar.

—Genesis 8:20

And God spake unto Noah, and to his sons with him, saying,

And I, behold, I establish my covenant with you, and with your seed after you;

And with every living creature that is with you, of the fowl, of the cattle, and of every beast of the earth with you; from all that go out of the ark, to every beast of the earth.

And I will establish my covenant with you; neither shall all flesh be cut off any more by the waters of a flood; neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth.

And God said, This is the token of the covenant which I make between me and you and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations:

I do set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant between me and the earth.

—Genesis 9:8-13

After discussing class members’ impressions of the story, share these two different interpretations to demonstrate what the text can mean to different people from different backgrounds. Some of these thoughts may echo themes class members have already noticed; if so, you may bring up quotes from these interpretations to support class members at the time they mention these themes. If not, you can bring up these texts afterwards to expand their understanding of the multiple layers of meaning within the text.

Noah’s Ark as a Parable about Forgiveness and Second Chances

God created humanity with love. In God’s very own image. With God’s very breath inflating our lungs. God is the natural architect. Designing and delighting in her creation.

And so, I can imagine how God seeing such wickedness and evil coming from us – God’s own creation – would be devastating. How God, like a potter, would need to throw the clay aside and start all over again. Making something new.

But God didn’t destroy everything. God found one good piece in the creation through Noah. And God decided to recycle. To take this one person. This one family. To use for God’s good. To take a few animals of every species and to build for them an ark. A safe place. A haven. To care for their needs and bring them to life on the other side of the storm.

God did destroy. In our story. God saw the wickedness and God destroyed the evil for justice-sake. But, God also saved. God washed clean. God made new.

The story of this flood and of Noah’s ark is a resurrection story for us. A story of God’s immense love for us. God’s desire to give justice out of love and God’s expansive forgiveness that begins first with Noah and by the end extends to all of us.

When Noah disembarks the ark, when he knows it is safe, the VERY FIRST thing he does is build an altar to God to worship and say “thanks.” Let me lay this out a little more…After forty days (or maybe a year) of living in a smelly zoo of animals…. on a boat with sea legs… probably out of food and patience and energy… The VERY FIRST thing Noah does is build an altar to God and say thanks.

…Noah’s act of worship prompts the very best part of the story: The covenant. The promise. The rainbow.

It is then in the story that God tells Noah: I will never destroy the earth ever again. Not only do I forgive you this time. But when you mess up – which you will mess up, God notes – I will forgive you always.

—Rev. Dawn Hyde, September 8, 2015, Noah’s Ark

Noah’s Ark as a Parable about Spiritual Preparation

We all need to build a personal ark, to fortify ourselves against this rising tide of evil, to protect ourselves and our families against the floodwaters of iniquity around us. And we shouldn’t wait until it starts raining, but prepare in advance. This has been the message of all the prophets in this dispensation, including President Hunter, as well as the prophets of old.

Unfortunately we don’t always heed the clear warnings of our prophets. We coast complacently along until calamity strikes, and then we panic.

When it starts raining, it is too late to begin building the ark. However, we do need to listen to the Lord’s spokesmen. We need to calmly continue to move ahead and to prepare for what will surely come. We need not panic or fear, for if we are prepared, spiritually and temporally, we and our families will survive any flood. Our arks will float on a sea of faith if our works have been steadily and surely preparing for the future.

—Elder W. Don Ladd, October 1, 1994, Make Thee an Ark

Do either of these interpretations resonate with you? Why or why not?

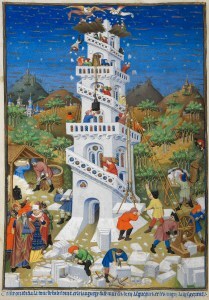

The Tower of Babel

Building of the Tower of Babel, Bedford Master

Invite class members to read these verses from Genesis 11:1-9, or to simply describe the Tower of Babel story as they remember it. As you read or talk about the story, consider these questions:

Why might ancient peoples have chosen to pass down this story?

What truths can we learn from this story that apply to our modern world?

How does the story inspire you? How would you apply its truths to your own life?

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.

And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there.

And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them throughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar.

And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded.

And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.

So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city.

Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

—Genesis 11:1-9

After discussing class members’ impressions of the story, share these two different interpretations to demonstrate what the text can mean to different people from different backgrounds. Some of these thoughts may echo themes class members have already noticed; if so, you may bring up quotes from these interpretations to support class members at the time they mention these themes. If not, you can bring up these texts afterwards to expand their understanding of the multiple layers of meaning within the text.

The Tower of Babel as a Parable about the Need for Diversity

When God created the first man and woman, God blessed them: “Be fertile and increase, fill the earth” (1:28). And after the flood, God blessed Noah by reiterating the very same words: “Be fertile and increase, and fill the earth” (9:1). If a key part of God’s primordial blessing and charge to humanity is that we spread out and fill the earth, how can God’s scattering humanity be a punishment? It isn’t, exactly.

…God had made it clear that the divine vision is for humanity to spread out and fill the earth, yet the builders want to stay put, to congregate in one place. In fact their resistance to God’s blessing is clear: they explicitly declare their intention to build their city, and the tower within it, out of fear “lest we be scattered all over the world” (Gen. 11:4). What they most fear is what God most wants.

…If everyone speaks “the same language” and utilizes “the same words,” then perhaps by implication they think the same thoughts and hold the same opinions. Perhaps, then, this story isn’t really about unity but about uniformity, which is much different.

Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin (commonly known as the Netziv, 1816–93) observes that although the opening verse tells us that the builders all had “the same words,” it never tells us anything about what those words actually were. That, he argues, is precisely the point: “God was not distressed by what they said, but by the fact that their words [and by implication, their thoughts] were all the same” (Ha’amek Davar to Gen. 11:1). God finds this unanimity alarming, because total uniformity is necessarily a sign of totalitarian control—after all, absolute consensus does not happen naturally on any matter, let alone on every matter.

Soon enough, the Netziv tells us, God’s concerns prove to be well founded: the builders refuse to let anyone leave their city (“lest we be scattered all over the world”). “This was certainly related to the ‘same words’ they all shared,” the Netziv argues. “They feared that since not all human thoughts are alike, if some would leave they might adopt different thoughts. And so they saw to it that no one left their enclave.”

…The builders wanted Babel to be the capital of the world, the Netziv contends, and the center of ideological enforcement: “It is inconceivable that there would be only one city in the whole world. Rather, they thought that all cities would be connected and subsidiary to that one city in which the tower was to be built.” This enforced consensus, he says, explains the building of the tower: the skyscraper would serve as a watchtower from which to monitor the residents and keep them in line (Ha’amek Davar to Gen. 11:4).

…An attempt to root out human individuality is an assault on God. Jewish theology affirms that each and every human being is created in the image of God and that our uniqueness and individuality are a large part of what God treasures about us. To try and eradicate human uniqueness is to declare war on God’s image and thus to declare war on God. The story of Babel ends with God’s “reversing an unhealthy, monolithic movement toward imposed homogeneity,” writes Hamilton, and thus with God’s reaffirmation of the blessings of cultural, linguistic, and geographical diversity.

—Rabbi Shai Held, October 24, 2017, The Babel story is about the dangers of uniformity

The Tower of Babel as a Parable about the Dangers of Pride

The tower itself wasn’t the problem. The sin was in thinking they could build a tower that could reach to God in Heaven. (St. Augustine sees pride in that they thought they could avoid a future flood (as if anything could be too high for God!) (Tractates on John 6.10.2).) The later verse calling this place Babel is significant. Babel is a Hebrew word meaning “gate of God,” or by extension, “gate of (to) heaven.” What they really think they can do is to ascend to Heaven, and God, by their own strength. Bad idea! Remember, Adam and Eve had been barred from paradise because they could no longer endure the presence of God. Never think that you can walk into God’s presence by your own unaided power. Only grace can do this. We cannot achieve Heaven by our power. We do not have a ladder tall enough or a rocket ship powerful enough. To make matters worse, they say, let us make a name for ourselves. Not only are they seeking to enter Heaven by their own power, but also to make a name for themselves.

…The text goes on to say,And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the sons of men had built. This great tower, so high as to reach to the heavens, was really so puny that God had to come down to see it.

What is God worried about? The text describes God’s concern for the growing pride of the human race: If now … they have started to do this, nothing will later stop them from doing whatever they presume to do.

…Our greatest enemy is pride. In terms of our salvation, the greatest virtue is humility. Unity is indeed a good to be sought, but if it fuels our pride, we’ll all just end up all going to Hell together! In this case God saw fit to humble us by scattering us and confusing our language. Unity in wickedness is best scattered. Only unity for good is praiseworthy. Of this St. Jerome says,

Just as when holy men live together, it is a great grace and blessing; so likewise, that congregation is the worst kind when sinners dwell together. The more sinners there are at one time, the worse they are! Indeed, when the tower was being built up against God, those who were building it were disbanded for their own welfare. The conspiracy was evil. The dispersion was of true benefit even to those who were dispersed (Homilies 21).

Bringing it close to home. To those who like to build and to make a name for themselves, St. John Chrysostom has this to say:

There are many people even today who in imitation of [the builders at Babel] want to be remembered for such achievements, by building splendid homes, baths, porches, and drives. I mean, if you were to ask each one of them why they toil and labor and lay out such great expense to no good purpose, you would hear nothing but these very words [Let us make a name for ourselves]. They would be seeking to ensure that their memory survives in perpetuity and to have it said, “this house belonged to so-and-so,” “This is the property of so-and-so.” This, on the contrary, is worthy not of commemoration but of condemnation. For hard upon those words come other remarks equivalent to countless accusations—“belonging to so-and-so, the grasping miser and despoiler of widows and orphans.” (Homilies on Genesis 30.7).

Do either of these interpretations resonate with you? Why or why not?

January 18, 2022

Our 5th Sacred Text

Do you remember that one General Conference? That one when we all raised our hands and sustained the Handbook as holding more authority than scripture, or common sense, or the spirit?

Do you remember that one General Conference? That one when we all raised our hands and sustained the Handbook as holding more authority than scripture, or common sense, or the spirit?

I was surprised, too! I mean, really, it was about time! Ever since the secret and not-as-secret Handbook one and two merged into one and went public, we were finally able to know what to do for everything!

I mean, when I was little and my mother was primary president of our (then) branch, she used to have a bulletin board where we would pin drawings of Jesus that we coloured ourselves. Thankfully, that wickedness was removed in section 35.5.1 where it says only approved artwork (and no bulletin boards) should be shown… ‘cause clearly my 4-year-old hands made colourings that were spirit-reducing rubbish. Phew!

And when I was a Young Woman in my (then) ward, and one of the Young Women teachers was a professional ballerina, she used to hold occasional free dance classes for members and (“not yet” member) friends of ours. It was her idea that getting people in the building was among the first steps to conversion, because they were in a building that was filled with the spirit. We know now that was just plain hogwash. “Holding organized athletic practices” “not sponsored by the Church” are not allowed (35.5.2.3). Phew! Glad I know this now. Wish I had known it back then! I would not have handed out nearly as many Books of Mormon had I known we were trespassing the Handbook.

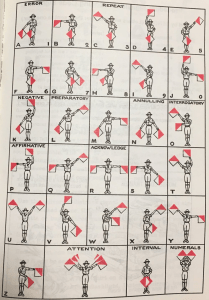

One time, when I was a Young Single Adult, when we had a cultural night in the building, wherein we hung flags of different countries (when available) by platters of gloriously unusual foods and games. I loved it! The presentations from different returned missionaries about the places they had served, and learning about different states as well as countries… well, now we know that is just plain wrong. Section 35.5.6 in the sacred Handbooks states “The national flag may be flown on Church property as long as local guidelines are followed.” It says nothing about non-national flags. Or even state flags! Thank goodness we no longer have Boy Scouts doing semaphore badges!

One time, when I was a Young Single Adult, when we had a cultural night in the building, wherein we hung flags of different countries (when available) by platters of gloriously unusual foods and games. I loved it! The presentations from different returned missionaries about the places they had served, and learning about different states as well as countries… well, now we know that is just plain wrong. Section 35.5.6 in the sacred Handbooks states “The national flag may be flown on Church property as long as local guidelines are followed.” It says nothing about non-national flags. Or even state flags! Thank goodness we no longer have Boy Scouts doing semaphore badges!

Because saying nothing is as powerful as saying something, amiright?*

For example, because the handbook does NOT specify that a woman CAN hold her baby in the baby blessing/ child of record practice, obviously she can NOT. (A friend’s bishop told her this. My bishop and I disagreed, but — hate to say this– we are in the same church. Not the same ward or stake or even country… but in the same church. Whoa. One of us is astray!)

So… according to may church member I have interacted with, if it isn’t in the church Handbook, it can not happen!

That being said, I do confess to making a meal for a family in need who were not members of my ward. I did not consult the handbook for fear that it would be wrong of me to do this because…. (whisper please) … because it was on the sabbath. I found no instruction, so did it anyway. Feeling that unrestrained was … dare I say… spiritually liberating? Obviously not a feeling we want to teach given the ridgid holdings many take of the Handbook.

And when our house was flooded last week, the handbook did not specifically tell anyone to come and help us move furniture, and yet, a member of the Elder’s Quorum did so… of his own volition. That seems wrong, given the Handbook and all—but it felt right. His wife even made us cookies—a recipe of which was also not found in the Handbook. (Obviously a little suspicious, but we ate them anyway. They were ridiculously delicious and I regret not having photographed them because the looked like perfectly made chocolate chip cookie mini pizzas).

I could go on. But why should I? I don’t need to follow the prophet, or think for myself, seek for the spirit or anything else, right? Certainly not when I have the Handbook.

Oh! But getting back to where I started… do you remember that general conference? The Handbook standing at the podium, after we all sustained it as holding more authority than scripture, or common sense, or the spirit? Or something like that?

Me neither.

Why do we treat than Handbook like scripture? Even in place of scripture? Even in place of canonised scripture?

I don’t know, either. I mean, I get it—in the world of GPS, we want to be exactly directed, in spite of road construction, in spite of potholes, in spite of visual clues, in spite of driving to the same place, at the same time, sometimes day after day after day… we want something else to take responsibility for decisions that might impact and hurt others.

But here’s the thing: It’s happening anyway. The impact. The hurt. Maybe even more so, with blind obedience to… the Handbook.

So I’m saying is… that sometimes, if not most times, relying on the spirit and common sense would be a more rewarding and inspirational experience than bearing witness of a non-canonised item that we reference way too much.

Way. Too. Much.

WAY. TOO. MUCH.

Let’s not do that anymore.

*Tee-hee— (38.3.1) the handbook does NOT specify the length of women’s skirts or dresses in the temple. It specifics sleeve length (“long” or “three quarter”), but NOT skirt length. There is nothing about covering the calves, or ankles. Common sense tells me that an ankle-length dress or skirt is preferred… but if it isn’t in the handbook….miniskirt Tuesday? Who’s in?

January 17, 2022

Why Don’t We Respect Relief Society Presidents Enough to Give Them an Office?

Relief Society Presidents are famous for doing a lot of work.

I’ve heard it said many times that a ward Relief Society President works in a partnership with her bishop to run their ward together. I’ve also heard it said that the Relief Society President is basically the female equivalent, and even equal to, the bishop in her ward. I object to these conclusions for many reasons (which are another post unto themselves), but I was specifically thinking today about why the bishop and stake president get their own offices in church buildings, yet neither the ward nor stake Relief Society President do.

I live in Utah County, Utah, and it’s not unusual to hear people discussing church business in public places, and this week while lifting weights at the gym I overheard two women discussing the church and current covid protocol. One of them was married to an LDS bishop, and the other was asking about his experience serving in a pandemic. The omicron variant has been surging in Utah the past couple of weeks, and we’re smashing new daily case records left and right. My school district is in the middle of an emergency five-day online learning break, Hamilton performances in Salt Lake City were just postponed because of a covid outbreak in the cast, and my daughter’s volleyball practice was canceled this weekend. It feels a little bit like March of 2020 all over again. The woman at the gym asked the bishop’s wife, “Do you think we’ll go back to at-home church?” The bishop’s wife said, “Oh, I hope not! That was so hard for my husband to deal with.”

The woman went on to explain the things her husband disliked so much about leading his ward remotely, and three of the things she talked about specifically had to do with missing his bishop’s office. He hated not being able to meet with people face to face for interviews. It was hard for them to hold bishopric meetings over zoom, because it was difficult to concentrate with all of the distractions and noise in their homes. And finally, (she mentioned as a side note) he missed seeing primary kids on their birthdays, when the Primary President used to give them a coupon for a handshake and a piece of candy, redeemable at the bishop’s office. (This stopped at the beginning of the pandemic and hasn’t resumed even with in-person church in their ward.)

A bishop has a physical office in his church building where ward members, primary kids, and even visitors can seek him out. I imagine that a confidential conversation works better in an office than inside a bedroom closet over zoom because of the privacy it affords both parties. I also understand wanting to have bishopric meetings in a comfortable chair with your desk in front of you to put papers and take notes on. I especially can appreciate the fun of having children come to see you every week, excited to be recognized and get a treat.

Has anyone considered that a Relief Society President might appreciate the same level of privacy when meeting with a family to discuss their temporal needs? I’ve seen Relief Society presidency meetings that take place in empty classrooms, notebooks balanced on the women’s laps until the next ward kicks them out for the start of a Sunday School class. The luxury of a desk is not offered to the ward’s top female leader, and no one sends primary kids to see her on their birthdays.

On the other hand, the primary children learn songs about the bishop, get a message at the beginning of each month from a bishopric member, see these men on the stand each week, and even have primary lessons teaching them about who and what a bishop is.

At least twice I personally took a primary or nursery class on a field trip to the bishop’s office, but it never crossed my mind to do the same thing with the ward Relief Society President. And honestly, how would we? Where would we find her and meet with her if it was a busy Sunday with multiple wards using the building? In the hallway, or out in the parking lot by her car? She doesn’t have a home base anywhere.

Despite the pandemic and reports of wards and stakes collapsing worldwide, my corner of the world is still actively building new church buildings and dividing wards. Our growth here is steady as new neighborhoods go up and we experience an influx of Latter-day Saints from other states like California. Why not carve out a little office space in one of the brand-new buildings for the ward Relief Society Presidents? (Or what about for the Stake Relief Society President? Could she have an office in a new stake center?) These women take notes on their laps and use kitchen tables for desks, while the male leaders can close the door and focus without distractions. Why can’t women in the church have equal working conditions to the men?

Is that really too much to ask?

The bishop meets with his counselors in his office at the church, while the Relief Society President meets with her counselors at a kitchen table in her home. As a mom, I bet she’ll be interrupted 73 times by kids needing fruit snacks and fighting over a tablet before the meeting ends.

January 16, 2022

A Stone for Anger, Rage, and Forgiveness

My stone.

My stone.In March of 2020, I was taking a class titled Justice and Reconciliation at Luther Seminary and the professor assigned Desmond and Mpho Tutu’s The Book of Forgiving: The Fourfold Path for Healing Ourselves and Our World as a required text. I grew up with a concept of forgiveness that hurt me and others, with pressure to forgive immediately and never bring up the harm again in an attempt to forgive and forget. I was not looking forward to reading this book, as I had long thought of forgiveness as one more theological tool that enabled abuse and promoted silence around abuse within religious communities.

The kind of forgiveness that the Tutus described is different from what I was taught. In their book, forgiveness is a way to work through the feelings that surround being hurt, without an expectation that the issue will be resolved on an arbitrary timeline or that the hurt person must renew the relationship with the party that hurt them. The stated goal of forgiveness is healing, but there is never an expectation that the hurt will disappear. At the end of each chapter, there is a suggestion for a spiritual practice to accompany each particular stage of forgiveness. Early in the book, the Tutus instructs the reader to find a small stone, which represents a hurt for which the reader seeks forgiveness. When the reader has moved through the process of forgiveness, the Tutus suggest returning the stone to the place where it came from.

I picked up my stone in March 2020 and set it on the kitchen counter. I’d been trying to ignore a difficult situation, hoping that a workplace aggressor would stop the intermittent sexual harassment. When I saw the aggressor say something questionable to a junior colleague, I felt sick. I realized I needed to name what was happening to me, but I was also up for tenure later that summer. The only way to address the issue and make sure that the aggressor could not harm my tenure case was to report the issue to the Title IX office, which would protect me from retaliation. After a drawn-out process, a committee determined that my complaint would not be upheld.

It is hard to describe the full range of emotions that my stone represented. I felt sheer terror, knowing that I was destroying my working relationship with the aggressor. I poured a lot of effort into this working relationship hoping that the sexual harassment would just stop and I felt betrayed by the aggressor. I felt ashamed that I had not had the courage to confront the aggressor the first time it happened. I felt foolish and naive to have been the victim of ongoing sexual harassment. I felt significant loss at having to confront something I had tried so hard to ignore. I experienced intense anxiety over the ways in this situation might other working relationships if I was found out. I feared the ways in which my rollercoaster feelings about the whole situation would impact my family. I worried that others in my workplace would find out and judge me, as women are often judged as guilty when they are victims of sexual harassment. I did not want any of this, and yet reporting was the only real way to make the sexual harassment stop. The personal costs of this process were high.

While many people understand sexual harassment as misplaced desire or attraction, it can also take the form of bullying. The sexual harassment I experienced was bullying with unwanted sexual language. Sexual harassment undermined my dignity by making me feel ashamed and humiliated every time it happened. Over time, it eroded my self worth.

All of these feelings combined to create not just anger but rage. I knew that I needed to let myself feel my feelings, but this rage was powerful and consuming. I started taking long daily walks where I let myself feel my rage but without trying to stoke the fire of the rage. A lot of this walking looked like me rage-storming around the neighborhood, perhaps as many as fifteen hundred miles of rage-storming over 21 months.

For a brief period in 2021, I tried to deny my rage and insist to myself that I needed to be over it. I looked at my stone on the kitchen counter desperate for the rage to be gone. This only intensified my rage, leading me to want to quit my job immediately and metaphorically burn down everything in a 10 mile radius. I started to acknowledge my rage again and it settled to a more familiar level.

In late December of 2021, I set out on my evening walk, intent on checking in with my rage. I reached for it and, for the first time in nearly two years, it was not there. Worried that this was just a fluke, I waited a few more days. Are you there, Rage? It’s me, Nancy. But it was gone and I returned my stone to the path where I found it.

I’m still frustrated about this situation. I’m sure that the anger will come back for brief periods. But the consuming rage I have been experiencing has not returned, even if the hurt remains. I did not let it consume me, though it came close, and eventually my rage burned itself out. This process helped me heal my relationship with myself so that I could move on. This was forgiveness.

January 14, 2022

Family Home Evening, Les Miserables, and Teaching Ethics to the Kids

I didn’t grow up doing Family Home Evening. In my small, less-than-orthodox family with a widowed mother and one brother, having a formal night of churchy lessons probably struck my mom as superfluous.

I didn’t grow up doing Family Home Evening. In my small, less-than-orthodox family with a widowed mother and one brother, having a formal night of churchy lessons probably struck my mom as superfluous.

My husband, however, grew up in a large active Mormon family, and FHE was a thing they did regularly. He’s been wanting to be more regular with FHE with our three kids (ages 9 to 15). Usually, I let him plan and carry these out, as I’m less committed to the idea of FHE. But occasionally, I take control. I’ve grown fonder of the idea of FHE ever since I realized that under the FHE label, I could commandeer a half hour or so of everyone’s time and force the whole family to talk about/watch/read what I want to.

A few months ago, I decided we would have a series of lessons based around the movie musical Les Miserables. When I taught Christian ethics at a Catholic women’s college a few years ago, I used the movie to discuss various ethical orientations, so it was a pleasure to pull out the movie again and introduce my kids to it and to some (very basic) ethics.

When I first took a grad class in ethics over a decade ago, I felt totally enlightened. I loved that there were these different ways people went about figuring out what was moral, just, and good. I’ve never been particularly inspired by emphases on goodness and morality stemming from obeying commandments and listening to prophets, which was largely the kind of morality discourse I heard at church. So learning about feminist care ethics, womanist ethics, virtue ethics, liberationist ethics, etc. gave me so many richer ways to think about morality.

Here’s a very brief rundown of talking points and discussion questions I covered as we watched the first half of Les Miserables during 2 or 3 nights consisting of a half hour or so of the movie. I’d frequently pause the movie and ask questions.

Val Jean’s decision to steal a loaf of bread in order to feed his sister’s starving child. Was that the right ethical decision? Why? Was it right even if it was against the law and against Judeo-Christian notions of commandments? What role does poverty play in a decision like this? How do you decide when to go against laws and commandments?Val Jean’s decision to steal the candlesticks from the kind priest. Why did he do that? What was his ethical thinking in that moment? I described this as a moment of despair as he came to realize he was caught in a system that didn’t give him a chance of survival if he played by the rules. At this point, he adopts a law of the jungle kind of morality. He’s been beaten down and mistreated, and his desperate wish for survival leads him to this decision. This is a moment where you can mention liberationist ethics and its commitment to focusing on the poor and their suffering, and in particular, liberationist ethicists’ commitment to paying close attention to context and situation as they work for more just systems and communities.The priest’s decision to lie to the police, forgive Val Jean, and send him on his way with the means to survive and build a new life. One can see this kind of ethics as feminist care ethics, where the moral question is not “What is the rule? What is just?” Rather, the moral question is “What does this person in front of me need right now? How should I respond?” Feminist care ethics considers contexts and values relationality. So the priest ignores rules about lying and downplays Val Jean’s stealing. Instead, he lets care ethics drive his decision to give Val Jean a new start. What are the upsides of care ethics? What are the downsides?

Javert’s obsession with rules and laws. He represents deontological ethics, or rule-based ethics. This kind of ethics is generally less interested in context and more likely to issue universal prescriptions. Javert is so utterly devoted to rules and laws that there is no flexibility, no room for context or situation as he mercilessly pursues Val Jean. What are the upsides of rule-based ethics? What are the downsides?Fantine’s story. This is another opportunity to discuss the kinds of desperate decisions people in impoverished situations must make, when they are constrained and don’t have full autonomy. She ultimately becomes a prostitute in order to earn money to keep her child alive. A tragic decision born out of a system where she has no good alternatives and choices. Her agency is limited, and if she obeys the rules (don’t become a prostitute) she and her child will die. Can we blame her for this decision? Did she do the right thing? Again, as feminist and liberationist ethicists would emphasize, context must be taken into account. In her terrible situation, she probably ended up doing the most loving thing she could.

Val Jean’s decision to reveal himself as the convict and save the man arrested for his crime. I love the song “Who am I?” The last two-thirds of it is classic virtue ethics, which the title of the song points to. Virtue ethics isn’t concerned about rules. Again the main question is not, “What is the rule?” The question is, “What kind of person do I want to be?” His refrain of “Who am I?” focuses on character and integrity, not rules.Val Jean’s decision to help Fantine and take care of Cosette. I see this scene and this song, in which he finds Fantine dying, a strong example of care ethics. Javert is obsessed with following the letter of the law and putting Val Jean (and Fantine) behind bars, but Val Jean’s focus is on care, on promising Fantine he’ll take care of her child, on making good on that promise. His morality is centered on doing what Fantine and Cosette need him to do at that moment, and he’s willing to break rules (run from the law) in order to deliver that care.

This only covers the first half or so of the movie. We actually watched the whole movie and found many other moral decisions to discuss – Why do people start revolutions? Is violence ever justified? When? Why does Val Jean save Javert? Why does Javert kill himself?

The musical Les Miserables (I’ve never read the book) has always been powerful for me. The messiness of these decisions, the complexity of them, the impoverished context — and throughout, Val Jean’s determination to try to be a good person and make good on the second chance bought for him by the kind priest — have always struck me as profound and deeply interesting. Far more interesting than simplistic commandments and rules that don’t consider context and don’t consider constraints on autonomy, like poverty, sexism, and racism.

I don’t know what kinds of morality my children will ultimately embrace and adopt. But I hope they are moralities that privilege compassion, care, and integrity. May they remember Val Jean and his example as they forge their paths in life.

January 13, 2022

Guest Post: One Mom, Two Coming-Out Stories, Part Two

Guest Post by Anonymoys. Anonymous is a wife and mom who lives in an area with a high percentage of LDS people. She enjoys cooking, crafting, and gardening.

September, 2021: It was a Thursday evening. My husband was taking a shower. Our oldest child was in their room doing homework (I hoped). And our youngest child had just finished brushing her teeth, and was cuddling with me on the couch. It was almost her bedtime. I asked if she wanted me to read for a few more minutes. (Though she was in 5th grade and a was a good reader, she still liked having me read to her at night—fantasy series like Rowan of Rin and Harry Potter.) She said “No,” and then she said “Mom, close your eyes.” “Close my eyes?” I asked. “Why?” “Just close your eyes. I’ll tell you when you can open them.” “Okay,” I said with a smile, and I closed my eyes, playing along in what I was sure was just one of my daughter’s silly games. I heard a sound like paper rustling, but I obediently kept my eyes closed. A moment later, she said “Now you can open your eyes.”

Before me stood my 10-year-old daughter, holding a piece of paper on which she had written the words “I’m gay.” Once again, my brain seemed to be slow in processing the words. Gay? Wait, what? Gay? My first thought was that this was still some kind of game. But one look at my child’s earnest and tear-filled eyes, and I knew this was no joke. She crumpled into my arms, and I hugged her so tight. This time I was not crying, but she was, and I just wanted to make it better. Stupidly, I asked “Why are you crying?” And she told me how much it had been weighing on her those past few months, and how she didn’t know how to tell me. (Only later would I think back and realize that his normally laid-back and happy child had been unusually moody and high-strung that summer.)

The conversation that followed began with me not necessarily saying the right things. E.g. “But you’re only ten,” and “Maybe it will change as you get older.” But I listened to my daughter, and I told her that I loved her, and I told her “It’s okay” and “It’s not a problem if you’re gay.” And she stopped crying, and I saw the relief on her face.

By now my husband had finished his shower. I asked my daughter if she wanted to tell her dad, and she said yes. When he came into the living room, she showed him the piece of paper. He reacted much the same way I had. Because this time, neither of us had had any idea this was coming. It was a complete and total shock. There were no clues (or at least none that we had picked up on). My husband said the same wrong things I had said, and then he said the same right things. And then we hugged our child again and we said “It’s okay. We love you. Thank you for telling us.” And then, once again, I tried to think of how I could possibly explain this to my very devout LDS extended family. And then I cried, and then I made another appointment with my therapist, and once again she told me to take a deep breath, and to slow down, and to just take things one step at a time.

And that is what I did. And once again I thought, in wistful melancholy mingled with relief: “I’m so glad that we agreed not to force our child to go to church if she didn’t want to. I’m grateful that our oldest child is nonbinary, because that led to a path of safety for their younger sister. I’m glad she stopped attending because of Covid. I’m grateful she doesn’t want to go back. I’m glad that I left.” And I don’t think I can’t properly convey the deep sadness that I felt once again, in the midst of the solace these thoughts provided.

But my child is happier now. And for that I am grateful.

January 12, 2022

The Comforter

A familiar trope of the travelogue testimony is a narrative of a visit to a distant ward or branch, and how that meeting felt wonderful, even if (or especially if) the speaker could not understand the local language. This feeling is proof that the Church is true. Sometimes the congregation also hears a contrasting experience about how uncomfortable the traveler was in a Cathedral or other non-LDS sacred space and meeting. I feel reasonably confident that any readers with ward members wealthy enough to travel have heard some version of this anecdote.

To be perfectly fair in what is about to become a critique, I have felt similar feelings of comfort or discomfort. As an American living in France it was comforting to go to Church and hear familiar tunes, participate in familiar rituals, and follow a familiar schedule even if the text, language and personal experiences of the members were not American. It felt like I was home in a time when I felt so incompetent and flustered over the simplest things, like buying stamps or a metro pass. I also went to Mass a handful of times, in part because I was lonely and bored on Sunday with nothing to do all afternoon and at least with more church I’d be around people. The surroundings were beautiful but very unfamiliar, with winking candles and the smell of incense and echoing stone walls. I speak French well, but apparently not well enough to follow chanting and I don’t know enough about Mass to really guess what was going on. I felt very uncomfortable, and it wasn’t just the hard pew.

The scriptures teach us that the Holy Ghost is a spirit of comfort and a spirit of truth.

“And I will pray the Father, and he shall give you another Comforter, that he may abide with you for ever; Even the Spirit of truth; whom the world cannot receive, because it seeth him not, neither knoweth him: but ye know him; for he dwelleth with you, and shall be in you . . . But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you. Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid.”

(John 14: 16-17, 26-27)

We can receive a witness of truth by the feelings that the Holy Ghost gives us. People who have experienced this often describe that feeling as one of warmth, peace, stillness, happiness – comfort! And we can also receive warnings when we encounter situations that are dangerous spiritually or physically. Those feelings are often the opposite – an uneasiness, a desire to leave, a yucky feeling in our stomachs.

I think, however, that it can be too easy as members to assume that feelings of comfort or discomfort come from the Holy Ghost, and therefore our responses to those feelings are righteous ones. As a white person, it can be very uncomfortable to confront systemic racism, or to have a non-white person express pain and oppression at the hands of white people. The same is true of men listening to the experience of women within a patriarchy, or straight people listening to the experience of LGBTQ+ folks. It can be true for Mormons encountering other faith traditions, or people of any country encountering foreigners. Those feelings of discomfort can seem a lot like warnings from the Holy Ghost – maybe you want to leave, or you feel a clench in your gut, or just uneasy. Similarly, we might feel comfortable around people expression political opinions we share, or hanging out primarily with people who share our skin tone or cultural background.

This is what I think we need to say loud and clear in every lesson on the Holy Ghost:

Just because you’re comfortable, it doesn’t mean the Comforter is witnessing truth. And just because you’re uncomfortable, it doesn’t mean that you’re receiving a witness of untruth or wickedness.

I did many things as a missionary that made me profoundly uncomfortable: Talking to strangers, knocking on doors, sharing my vulnerable feelings. I almost always felt a desire to run away instead. That doesn’t mean what I was doing was displeasing to God or inconsistent with truth. I’m an introvert and in any case, proselytizing violates a lot of cultural norms around minding your own business and religion being a private matter.

I have also done or said things in my life that at the time comfortable, but which I now cringe to think of. “The Church isn’t sexist” is an example that springs to mind – it was the easy thing to say and it fit with what everyone around me wanted to hear. That doesn’t make it true. In middle school I was in the class production of “Peter Pan” complete with being a member of the “Indian” chorus who sang a song with the following lyrics: “Guk-a-bluk waaaah—hooo! Ug a wug ug a wug waahhh.” The choreography, costuming and makeup are as appalling as you might be imagining. I was uncomfortable only because of stage fright. That doesn’t mean God loves cultural appropriation and demeaning stereotypes.

I don’t have an easy answer for how to discern between the Comforter witnessing truth, and our own comfort with the familiar and the easy. I only want to suggest as we enter a new year at Church that we push a little harder on those questions in our classes and talks.