Ron Base's Blog, page 17

December 4, 2012

Trapped In A Snow Drift With A Legendary Movie Star, Television’s Biggest Actor, A Sex Symbol–and A Canadian Icon Named Pinsent

Reading through Next, Gordon Pinsent’s delightful autobiography (written with his friend, and mine, George Anthony), reminds me of the first time I got to know Gordon while we were trapped in a snow drift in northern British Columbia with one legendary movie star, Rod Steiger; one legendary TV cowboy, Lorne Greene; and one Hollywood sex symbol, Angie Dickinson–as curious and mismatched a cast of characters as I’ve ever encountered.

Reading through Next, Gordon Pinsent’s delightful autobiography (written with his friend, and mine, George Anthony), reminds me of the first time I got to know Gordon while we were trapped in a snow drift in northern British Columbia with one legendary movie star, Rod Steiger; one legendary TV cowboy, Lorne Greene; and one Hollywood sex symbol, Angie Dickinson–as curious and mismatched a cast of characters as I’ve ever encountered.

This unlikely group had gathered together to film a movie titled Klondike Fever, a fictionalized account of author Jack London’s early days in the Canadian wilderness. Gordon was playing a real-life character named Swiftwater Bill, and the shoot was taking place in a remote little town called Barkerville, an original gold rush town that had been preserved in the B.C. interior just the way it was in the 1860s.

This unlikely group had gathered together to film a movie titled Klondike Fever, a fictionalized account of author Jack London’s early days in the Canadian wilderness. Gordon was playing a real-life character named Swiftwater Bill, and the shoot was taking place in a remote little town called Barkerville, an original gold rush town that had been preserved in the B.C. interior just the way it was in the 1860s.

The star of the movie was a young unknown named Jeff East, but all eyes were on Steiger, who was playing the villain of the piece. No doubt about it, he was a mesmerizing figure, the actor who had played Marlon Brando’s brother in the classic On The Waterfront, the Academy Award-winner for his role as the Mississippi police chief in In The Heat of the Night.

Since then, however, Steiger’s career had fallen on hard times. Still, when he was doing a scene you could not take your eyes off him, and when he walked into a room, he was a commanding presence. He was a star, and he didn’t mind letting you know it–albeit with a twinkle in his eye.

Certainly he appeared amused to find himself trapped in this snowy, mountainous nowhere on the eve of his fifty-fifth birthday–a birthday celebrated one night at a local tavern with an impromptu concert, Steiger singing at the microphone, backed by the local band, singing surprisingly well, too.

It was fascinating to watch him go after the veteran Lorne Greene, Ben Cartwright himself from Bonanza, one of the longest-running and most popular shows in the history of television. Greene turned out to be as weird as a wombat, and Steiger vastly enjoyed teasing him when everyone got together in the evening.

Greene tried his best to play along, but he was no match for Steiger, and it was obvious he was not vastly enjoying any of it. Angie Dickinson reacted to all this male jousting by simply steering clear of it, and keeping to herself in her motel room.

Greene tried his best to play along, but he was no match for Steiger, and it was obvious he was not vastly enjoying any of it. Angie Dickinson reacted to all this male jousting by simply steering clear of it, and keeping to herself in her motel room.

The one person Steiger treated as his equal was Gordon Pinsent. The Newfoundland-born Pinsent was one of the few true Canadian stars the country had produced at the time. He had starred in two hit TV series, Quentin Durgens, M.P., and A Gift to Last, both for the CBC, and had starred in and written one landmark Canadian film, The Rowdyman. He had also written novels, a play, and even a musical version of The Rowdyman.

There are few people who can resist Pinsent’s effortless charm, and certainly Steiger wasn’t one of them.If Lorne Greene was no match for Steiger, Gordon Pinsent most certainly was. By the time I got to the location to do a story on Pinsent for TV Guide, they had become fast friends.

This story is contained in Next, although I tell a slightly different version of it. Gordon and I were on our way to lunch one afternoon when we encountered Steiger. “Come to lunch with us, Rod,” Gordon urged.

Steiger complained that if he went outside, he would have to deal with the public recognizing him. “Oh, come on, Rod,” Gordon said. “It’ll be fine. No one will bother you.”

Finally, Steiger relented and off the three of us went to a nearby restaurant. When we arrived, the place was nearly deserted.The hostess seated us, without giving any indication she recognized anyone. Steiger began to relax.

Then the waitress started across the room toward us. As she approached, you could see her eyes widen in surprised excitement. Her face began to glow. When he saw this, Steiger groaned. “Oh, no. Here we go.”

You could see him brace himself.

The waitress broke out a welcoming smile. “Gordon Pinsent!” she exclaimed. “I can’t believe it’s you!”

Steiger’s face fell. He looked over at Pinsent in a way he had not looked at him before. Meanwhile, the waitress continued on enthusiastically about how much she had enjoyed Pinsent on television over the years and what a thrill it was to finally meet him.

Steiger was not reacting at all well to this. It is one thing to say you don’t want to be recognized; it is quite another to actually go unrecognized. Finally, Gordon, sensing the effect this was having on his friend, interrupted the waitress to say, “You should meet Rod Steiger, he’s here, too.”

The waitress, looking confused, held out her hand and said, “Nice to meet you, Rob.”

I don’t think Steiger ever recovered.

In his memoir, Gordon goes on to relate how Klondike Fever received what was then a Genie Award nomination for the year’s best Canadian film (Gordon in fact won a prize for his role in the picture).

In his memoir, Gordon goes on to relate how Klondike Fever received what was then a Genie Award nomination for the year’s best Canadian film (Gordon in fact won a prize for his role in the picture).

In the curious world of our homegrown cinema in those days, the movie managed to get a nomination before anyone had even seen it. In fact, I don’t believe Klondike Fever was ever released theatrically to any extent. I never saw the film until several years later, and today it is one of the forgotten anomalies of the Hollywood North days when huge tax breaks allowed all sorts of bizarre movies to be made without ever being seen.

Curiously enough, ten years later, I ended up back in Barkerville as the co-writer of a French movie that, to my amazement, had chosen the town as one of its locations. I went back to the tavern where Steiger had celebrated his birthday. There on the wall, preserved for posterity, were photographs of Lorne Greene and Angie Dickinson and Rod Steiger with his famous pal, Gordon Pinsent–ghosts from a nearly forgotten past.

Gazing at the photos, I remembered my time in a snow drift with Gordon and smiled–much the same way I did the other day when I finished reading his wonderful autobiography. You can do a lot worse in a lifetime than have lunch with Gordon Pinsent.

Particularly when it includes the oh-so-famous Rob Steiger.

November 18, 2012

The Art of Peeling Grapes In Barcelona

BARCELONA–We meet Chef Papa Serra first thing in the morning outside the sprawling Boqueria Market, expecting a porcine Spaniard with a beard, exuding twinkling-eyed Bonhomie mixed with sage observations about life and food.

BARCELONA–We meet Chef Papa Serra first thing in the morning outside the sprawling Boqueria Market, expecting a porcine Spaniard with a beard, exuding twinkling-eyed Bonhomie mixed with sage observations about life and food.

Instead, a trim twenty-eight-year-old New Zealander in a white chef’s coat shows up armed with a bottle of Cava and two wine glasses.

“I don’t look Spanish and I don’t sound Spanish, but I cook as if I was born running amongst the bulls,” assures Joel Serra Bevin. He is second generation Catalan, who, in addition to growing up in New Zealand, has spent time in Australia, London, and New York before relocating to Spain in 2010.

Joel today will guide us through not only the culinary delights of Barcelona’s most famous market, but also introduce us to the secrets of Spanish food, and then cook us an excellent lunch, helped immeasurably by yours truly, who turns out to be the unexpected master of the art of peeling a grape.

The Boqueria Market is something to behold, the biggest and most popular of the twenty markets scattered throughout the city, first established, according to Joel, in the 1860s when Barcelona was still basically a Medieval town with a wall around it.

Unlike a lot of other markets, this one is permanent. These stalls beneath the market’s vast canopy just off La Rambla, the city’s main pedestrian thoroughfare and a major tourist haunt, constitute the most valuable real estate in Barcelona. Owners pass their stalls from generation to generation. Merchants here are permanent fixtures. They even have their own Facebook pages.

You make your way through the labyrinthine aisles that snake through the market, past glassy-eyed monk fish that were swimming in the Mediterranean a couple of hours ago; armies of crabs and lobsters that are still moving; thick pallets of salted cod; gleaming glass bottles of saffron, the fifth most expensive product in the world (each strand must be dried separately); Ostrich eggs the size of Easter eggs; great legs of Jamón Ibérico de Bellota, cured for a year and considered the finest ham in the world (it comes from black pigs who are fed bellota or acorns).

You begin to realize, aided by a helpful whisper from Joel, just how important food is to the Spanish.

The French and the Italians are much noisier about their love of food. The Spanish seem more content to stay home and eat rather than boast about it to the world. It may be blasphemy to say so, but you can get a better meal at much more reasonable prices in Barcelona these days, than you can in Paris.

Nothing is processed here. There is no such thing as industrial farming. Everyone still goes to the market daily. People are fresh-obsessed. They want to see the scales on the fish, the head of the chicken.

Nothing is processed here. There is no such thing as industrial farming. Everyone still goes to the market daily. People are fresh-obsessed. They want to see the scales on the fish, the head of the chicken.

This almost fanatical care with and concern for food and its preparation is reflected in the city’s restaurants. Tapas, of course, is the preferred method of eating, small portions of a number of dishes that can include squid, monk fish, various meat dishes, and lots of succulent vegetables: eggplant, peppers, olives, tomatoes.

At the very popular La Paradeta, you choose the fresh fish you want, they cut off a hunk right there in front of you, cook it, and then serve it in a caferteria-style atmosphere that nonetheless has people lined up out the door waiting to get in–and this is in a country where the economy is in a shambles, and there is twenty-five per cent unemployment, the highest in the western world.

Nobody seems to be suffering too much over at Comerç24, considered for the moment the hottest restaurant in Barcelona. You can’t get into the place on a Friday or Saturday night. We have to be satisfied with lunch, but whatever time of day you eat there, the tapas is delicious, served on flat pieces of marble. By the time the bill arrives, concealed in a handsome wooden box, the place has certainly lived up to its reputation.

If you’re looking for history, and a stately, enduring sense of Barcelona’s past, you can find it at Quatre Gats–the Four Cats. It’s been around for more than a century and is famous enough that Woody Allen shot scenes for Vicky Cristina Barcelona here (his picture is on the wall).

This is also where the great Catalan artist, Pablo Picasso, hung out when he first came to Barcelona in the 1920s. In fact, the cafe sponsored his first art show. One can spend the morning at the Picasso museum, marveling at what Picasso achieved as a more traditional artist by the time he was fourteen, and then wander over to Quatre Gats for–what else–a tapas lunch.

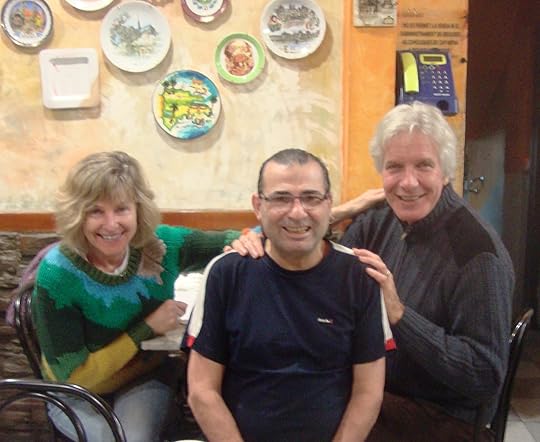

But the good meals are not restricted to Barcelona’s famous restaurants. We wander around the corner from our apartment in the trendy el Born quarter and find a charming dinner at a corner bistro called La Catonada where the hostess stands on the street, persuading customers to enter, and where the owner, undaunted by the fact you speak little Spanish and he speaks little English, carries on a lively conversation and then insists on having his photograph taken with you.

But the good meals are not restricted to Barcelona’s famous restaurants. We wander around the corner from our apartment in the trendy el Born quarter and find a charming dinner at a corner bistro called La Catonada where the hostess stands on the street, persuading customers to enter, and where the owner, undaunted by the fact you speak little Spanish and he speaks little English, carries on a lively conversation and then insists on having his photograph taken with you.

Still, there is nothing like a home-cooked meal, even in Barcelona, and with some help from my wife Kathy and myself, Papa Serra, aka Joel, is preparing just such a repast. At noontime we have returned to the apartment Joel uses to entertain his guests.

The novice chef–me–is once again astonished at the preparation necessary for the creation of fine food. The making of the allioli, for example, is complicated and labor intensive enough to remind the novice chef that he will forever remain exactly that.

After a quick lesson from Joel, I am placed in charge of perhaps the most important part of the luncheon, the peeling of the grapes. We finally sit down to eat at two o’clock beginning with a tasty gazpacho that is refreshingly unlike the variations on V8 juice that Joel says constitutes most gazpachos–this is where my grape peeling has made all the difference.

The soup is followed by fresh sardines from the market that make you forget you were ever forced to eat a canned sardine. There is an exquisite lentil dish with a chorizo crust ensuring you will forever after love lentils; salted cod mounted on sheaves of endive lettuce, again, fresh from the market, and tasting like no cod you have ever had before. Even a spiced chicken leg possesses an original, mouth-watering flavor thanks to the romesco, a Catalan sauce created with almonds, peppers, and roasted garlic.

At the end of a very satisfying morning with Joel, topped by a superb lunch, I believe everyone agreed that the meal would not have attained nearly the brilliance it did without the properly peeled grapes.

I smile and try to look humble, knowing I have attained culinary heights, and mastered the art of peeling grapes in Barcelona.

November 11, 2012

With Brooke Shields’ Mother, Dancing On A Stove In Spanish Harlem

And then–I’m not quite sure how–Brooke Shields’ mother was in the kitchen of the restaurant in Spanish Harlem, dancing on the stove.

And then–I’m not quite sure how–Brooke Shields’ mother was in the kitchen of the restaurant in Spanish Harlem, dancing on the stove.

The music was playing loudly, the cooks and kitchen help were staring in amazement, as was I. Brooke Shields looked grim. Teri Shields was having the time of her life.

I thought of that night when I learned that Teri Shields had died at the age of seventy-nine. I suppose I wasn’t surprised, either at the news of her death or by the reports that Brooke and her mother were barely speaking.

How I came to be in Spanish Harlem with Brooke Shields, who at the time was the most notorious twelve-year-old in America, and her wild and crazy mother, well, there’s a story.

Brooke had just starred in Pretty Baby, a movie directed by the French filmmaker Louis Malle about child prostitution in the Storybook section of New Orleans in the early years of the twentieth century.

The film is all but forgotten now, but at the time it was hugely controversial, since it featured underage Brooke in the nude. For a time it was banned in Canada.

When I arrived in New York to interview her, Brooke Shields was the controversial flavor of the moment. She would inspire dozens of magazine covers and a whole Brooke look–Time magazine in its cover story about her called it “The 80s Look.” Everyone was clamoring to talk to her and Teri, a single mother who was acting as her daughter’s manager.

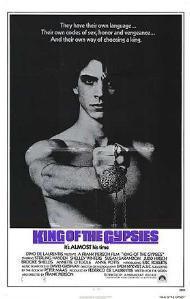

I met Teri on the set of the movie Brooke was currently shooting, King of the Gypsies, a drama about the secret world of the gypsies that had ambitions to become to gypsies what the Godfather was for gangsters. Brooke was co-starring with Susan Sarandon (who had also appeared in Pretty Baby) and Sterling Hayden, as well as another young newcomer, Eric Roberts (Julia’s older brother).

But all eyes were on Brooke.

Teri led me back to where Brooke was being made up. She was in full gypsy regalia. No doubt about it, she was a beautiful girl, and surprisingly self-possessed and well-spoken for someone so young and new to the game. She was quiet and serious and not particularly forthcoming, although when it comes to interviewing twelve-year-olds there is not, beyond a certain point, a whole lot to talk about.

Teri, however, was another matter entirely. She had once entertained ambitions to become an actress herself. Now that her daughter was famous, one got the impression that since she was only twelve and could not really enjoy celebrity herself, Teri would do it for her.

Brooke finished shooting for the day and Teri decided that we should all go out to dinner. Brooke wanted to go home. Teri wouldn’t listen. We would eat something in a favored restaurant nearby.

We took the elevator down. It came to a stop and a man got on. Teri sashayed up to the startled new arrival. She batted her eyelashes at him and said, “How do you like me so far?”

Brooke rolled her eyes.

We walked along a Spanish Harlem street to the restaurant, Brooke complaining she wanted to go home. I felt like an interloper in this ongoing mother-daughter drama, but I dutifully went along anyway.

Teri blew into the restaurant, and more or less took over the place, ordering drinks–copious drinks, it turned out–and food. She talked to everyone, aglow with her daughter’s moment of celebrity. If anyone should have been famous, it was Teri Shields. Brooke slumped forlornly against the wall, hardly saying anything.

Hours later, the meal finished, more wine was being poured. Brooke once again was demanding to go home. But now there was music and Teri was up and dancing around the restaurant.

Then she disappeared into kitchen. Brooke and I traded glances. I got up and went back to see what had happened to her mother. I stepped into the kitchen and there she was dancing on the stove.

I stood there, my jaw dropping, watching Teri sway to the music. Then Brooke appeared, saw what was happening, and ordered her mother off the stove. Teri looked wounded. What am I doing that’s so wrong? she seemed to be saying. I’m just having fun. What’s wrong with that?

It wasn’t hard to see that a weird transformation seemed to have occurred in the relationship between Brooke and her mother. The parent was the wild, immature child; the child had been forced into the role of the mature, responsible parent.

Brooke again ordered mother down from the stove. It was late, she said in a calm voice. She had to be at school the next morning. Teri finally acquiesced, and I helped her down to the floor. The air had gone out of the evening. The bill was paid, a cab was called, and we headed uptown away from Harlem.

They dropped me off at my hotel, and then Brooke and Teri went off into the night.

A few years later, Brooke was starring in a romantic tear-jerker titled Endless Love, the movie that was supposed to launch her adult film career. I happened to be in New York at the time, and ended up at the movie’s premiere party. There was a much taller Brooke, even more beautiful, but still quiet and removed from everything.

A few years later, Brooke was starring in a romantic tear-jerker titled Endless Love, the movie that was supposed to launch her adult film career. I happened to be in New York at the time, and ended up at the movie’s premiere party. There was a much taller Brooke, even more beautiful, but still quiet and removed from everything.

The friend who brought me to the party introduced us, and suggested we dance. To my amazement, Brooke agreed. On the dance floor I don’t remember us saying a single word to each other. If she recognized me, she gave no sign of it, and I decided not to say anything.

Later in the evening, I ended up standing beside Teri. She was much more subdued. I introduced myself and said we had met before, and had gone to dinner together in Spanish Harlem.

She looked at me blankly. “I have no idea what you’re talking about,” she said.

Endless Love failed at the box office and did not launch Brooke’s career as an adult movie star. But she has soldiered on in the business and managed to carve out a certain celebrity niche. Perhaps the best thing, she appears to have remained sane and grounded in the face of it all, much the same as she was the night the three of us went out together.

She has two children of her own now. There have been no reports of her dancing on stoves in Spanish Harlem.

November 7, 2012

When You Know Nothing, You Know Everything:Welcome To Barcelona

BARCELONA—When you finally know nothing in this fabled Mediterranean seaport city of five million, that is when you know everything.

Welcome to Barcelona.

Our guide through the vagaries and paradoxes of the world’s smallest big city— and the biggest small city—is José A. Peral Mondaza, intellect, historian, linguist, and all-round charmer.

José, fortyish, handsome in a bookish and bespectacled early Peter O’Toole sort of way (the non-blond O’Toole), is married to a Montreal teacher and therefore has spent time in Canada. He steers us through the medieval streets of Barri Gòtic, the gentrified pleasures of el Born (the new old city, where we have rented an apartment), the wide boulevards of the Eixample, the quiet neighborhoods of Gràcia. At the same time, he also eloquently articulates how the tangle of history, politics, and religion still complicates life here.

The politics are present in the Catalan flags draped from seemingly every balcony. You soon learn that you are not in the Spain you imagined before arriving here, but in Catalonia, the semi-autonomous state within Spain that many Catalans believe is not nearly autonomous enough.

This is a region that very much wants to be on its own, that feels betrayed by history, by the dictator Franco (who banned the Catalan language, one of many oppressors who tried to do that), and by the current Castilian-dominated Spanish government, that, according to many here, continues to go out of its way to alienate Catalans.

The long-running ill-will is exacerbated by a Nov. 25 state election, which almost certainly will lead to an independence referendum, and an economic crisis roiling the country leaving twenty-five per cent of the work force unemployed—an astonishing sixty-five per cent of young people are said to be without work.

José isn’t sure how everyone keeps going. He is as amazed as anyone that even at this non-tourist time of the year, the restaurants and cafes continue to fill with patrons tasting delicious tapas, and the throngs at noontime crowding La Rambla, the historic pedestrian mall, are as thick as ever. He believes disaster is coming, but there is no sign of it in the windows of the smart shops on the Passeig de Gràcia, the wide thoroughfare that reminds you so much of Paris. You can barely squeeze into Apple’s vast store for the crowds anxious to check out the new iPad mini.

José isn’t sure how everyone keeps going. He is as amazed as anyone that even at this non-tourist time of the year, the restaurants and cafes continue to fill with patrons tasting delicious tapas, and the throngs at noontime crowding La Rambla, the historic pedestrian mall, are as thick as ever. He believes disaster is coming, but there is no sign of it in the windows of the smart shops on the Passeig de Gràcia, the wide thoroughfare that reminds you so much of Paris. You can barely squeeze into Apple’s vast store for the crowds anxious to check out the new iPad mini.

At seven thirty, just before Cal Pep throws open its doors, the line of hopeful diners snakes across the square waiting to get into this popular tapas restaurant. Inside, a long counter seats twenty patrons at a time. The rest of us line up behind them against the wall, waiting for the next available stool. After an hour, we finally are ushered to a small table in a rear room. The tapas is great but not beyond anything available elsewhere in Barcelona without the wait.

To be sure, the situation is slightly less dire here where the Catalans have a reputation for industriousness—the rest of the country views them as the Germans of Spain. Catalonia’s outsider status is such that it is considered too far south to be north, too far north to be south. The locals grumble that the region annually sends sixteen billion Euros to the government in Madrid but doesn’t get nearly as much back.

Religion is everywhere, reminding the visitor of the grip God used to have on this country. It is most obviously represented here by the Sagrada Família, Holy Family, the magnificent cathedral that is to Barcelona what the Eiffel Tower is to Paris.

Even if you have seen photographs, nothing prepares for you for the electric jolt provided by the first sight of Sagrada Família’s incredible edifice. It is not only Barcelona’s but possibly the world’s, most dramatic and original testament to God, created by the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi, who devoted forty-three years to the cathedral (even now, it is not finished).

A deeply conservative and religious Catholic (he attended mass every day), Gaudi’s God was always present between the lines of his whimsical creations that appear to have tumbled out of a slightly cockeyed fairy tale—dreams in stone, the art critic Robert Hughes once called them.

Thus, with the aid of the insightful José, it is possible to get a deeper, more spiritual view of Gaudi’s Casa Batlló, the block of apartments dominating a corner of the Passeig de Gràcia. The bone-like columns supporting the lower stories are Gaudi’s assertion that life is fragile and comes to an end. All that keeps us going is the pleasure represented by the balconies in the shape of carnival masks.

But pleasure, Gaudi’s façade tells us, is not enough. (“Man is free to do evil,” he once said. “But he pays the price of his sins”). Pleasure leaves you finally alone as represented by a single upper window, and haunted by monsters—the scaled, undulating roof in the shape of a dragon. Finally, there is only God who can redeem the lost, lonely soul, therefore the cross rising triumphantly from the rooftop.

The architect’s employers, unable to see the God in Gaudi, were furious when they saw what his genius had wrought—begging the question of what they were doing while construction was underway. Up the street a few blocks, Senora Milà was equally unhappy when she saw what Gaudi had produced after he was hired to design an apartment complex. It was supposed to be called Casa Milà. Instead, the locals derisively nick-named it La Pedrera, the stone quarry. “I ordered a palace,” groaned Senora Milà. “Instead, I got a prison.”

The architect’s employers, unable to see the God in Gaudi, were furious when they saw what his genius had wrought—begging the question of what they were doing while construction was underway. Up the street a few blocks, Senora Milà was equally unhappy when she saw what Gaudi had produced after he was hired to design an apartment complex. It was supposed to be called Casa Milà. Instead, the locals derisively nick-named it La Pedrera, the stone quarry. “I ordered a palace,” groaned Senora Milà. “Instead, I got a prison.”

Even in these extravagant times, modern architecture seldom allows for Gaudi’s delightful excesses. Standing on the sidewalk before Casa Batlló, it is difficult to imagine how such a deeply conservative man could ever have created these fantastical works of unbridled imagination—works, incidentally, that remain fascinating but unsettling (even Gaudi’s architecture school teachers were uncertain whether they had graduated a genius or a madman).

So the crowds gather daily to gawk and to wonder. Meanwhile, not far to the north, amid the descending evening calm of the Gràcia quarter, José finishes his day with us, worrying that the Madrid government might one day act as intelligently where Catalonia is concerned as the government in Canada has acted with Quebec. “If that ever happened, the separatist movement here would fall apart,” he says. His wife, he says, used to be a Quebec sovereignist; no more. However, she is very much in favor of Catalan independence.

But then such are the contractions rampant in this fascinating old city. I realize after a few days here that while I understand nothing, I still don’t know much of anything, which means that although I can be a happy visitor here, I can never be a Catalan.

Welcome to Barcelona.

Ron Base’s new novel, Another Sanibel Sunset Detective, is now available. Check it out HERE.

November 2, 2012

That Afternoon With Henry Fonda

In a fit of nostalgia yesterday I pulled John Ford’s 1946 western, My Darling Clementine, off my DVD shelf and watched it on our new fifty-five-inch Sony television screen. Magical: it brings old movies to life again with a sharpness and clarity that is breath-taking.

In a fit of nostalgia yesterday I pulled John Ford’s 1946 western, My Darling Clementine, off my DVD shelf and watched it on our new fifty-five-inch Sony television screen. Magical: it brings old movies to life again with a sharpness and clarity that is breath-taking.

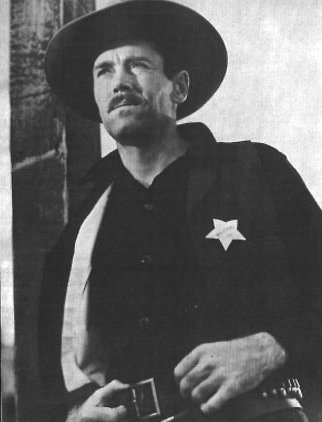

Seeing a young Henry Fonda as Wyatt Earp in a performance so fluid and natural that you forget this is a movie–at times you feel as if you are inhabiting a man’s life–brought memories flooding back. It would be unfair to say Henry Fonda has been forgotten in the years since his death in 1982, but as is the case with so many iconic stars from that era, he has certainly faded.

Not for me, though.

I was writing about television for The Windsor Star and Fonda was across the river in Detroit appearing at the Fisher Theater in a long-forgotten play titled The Trial of A. Lincoln. Fonda, who had previously played the role onscreen for John Ford, was playing Lincoln.

Somehow I managed to convince my editors that I should talk to Fonda about television (he had done a couple of short-lived TV series). But I had no more interest in his television views than I had in flying to the moon. What I wanted to discuss with Henry Fonda was his movies–from The Grapes of Wrath to 12 Angry Men to Once Upon A Time in the West. He had arrived in Hollywood, a young man from Nebraska, and had been appearing in films for nearly forty years.

I encountered him in the lobby of the small hotel where he was staying. “You’re early,” he snapped as we shook hands.

“Well, come on up,” he said, softening. “But you’ll have to wait until I’ve read my sports scores.”

I remember trailing him across the lobby, focused for some bizarre reason on the back of his neck, thinking, irrationally, This is the back of Henry Fonda’s neck. What can I say? I was young and highly impressionable.

Upstairs in his small apartment, he leaned on the kitchenette counter intently reading the sports section. Then he settled into a sitting room sofa and began to talk in the laconic, mid-western drawl that was so distinctive on the screen. He was dressed in a denim shirt and a pair of jeans, still whip thin at sixty-five and looking younger than his years (although at the time, barely in my twenties, I thought sixty-five ancient; it has become much younger over the years).

I had expected to talk to him for an hour or so surrounded by publicity people. Instead, it was just the two of us, and as the afternoon wore on the one hour became two and then three. The phone never rang. Shadows lengthened and evening fell, and I believe the only thing that stopped Henry Fonda talking through the night was the fact that he had to go to the theatre for an eight o’clock performance.

He talked frankly about why he had become an actor: “I don’t like myself, so I like becoming someone else.” He spoke, sadly, about his relationship with the great John Ford (they’d had a falling out shooting Mr. Roberts; Ford had actually struck Fonda), and said the director was ill and would never make another movie (which turned out to be the case). He talked about how director King Vidor was losing it while making War and Peace, and that had a lot to do with why the movie turned out to be so disappointing.

He was disgusted at some of the movies he had allowed himself to make for money, particularly The Battle of the Bulge. “They had me winning the whole goddamned war single-handedly,” he said angrily.

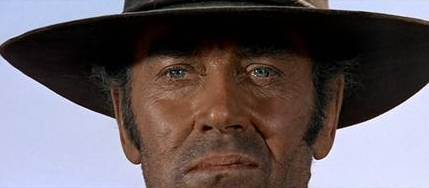

He told a great story about how he agreed for the first time in his career to play a bad guy in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. He showed up in Rome having carefully cultivated a beard and mustache for the part. Leone was appalled. “He made me shave immediately,” Fonda recalled. “‘I want Henry Fonda,’ he said. ‘You must look like Henry Fonda.’”

He told a great story about how he agreed for the first time in his career to play a bad guy in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. He showed up in Rome having carefully cultivated a beard and mustache for the part. Leone was appalled. “He made me shave immediately,” Fonda recalled. “‘I want Henry Fonda,’ he said. ‘You must look like Henry Fonda.’”

The fact that he had been married so many times, amazed and embarrassed him: “I can’t believe I ended up being married five times!”

After we finally parted company, I spent a lot of time wondering why Fonda spent so much time and was so painfully open with a young reporter who was a complete stranger.

I had the idea that he saw himself as something of an old shaman, sitting around the camp fire, passing down tales of an ancient Hollywood to the next generation–and I believe there was some truth to that. An entire era of movie-making was fast disappearing even back then, and I think he wanted to make certain some record of it was left behind.

In her autobiography his daughter, Jane Fonda, writes about the distance he kept from his family and how she seldom talked to him, and yet he would speak to strangers on a plane for hours. That would certainly help explain why he spent so much time with me.

But I think there was something else.

Several years later, now a feature writer in Toronto, I flew to Chicago to interview Fonda again. This time he was appearing in a much-more acclaimed one-man show playing Clarence Darrow.

We met at the Ambassador East Hotel where he was staying with his wife, Shirlee. He had aged considerably since our last encounter–which, incidentally, he only vaguely remembered (a valuable lesson in celebrity interviewing; you remember everything, they remember nothing).

We met at the Ambassador East Hotel where he was staying with his wife, Shirlee. He had aged considerably since our last encounter–which, incidentally, he only vaguely remembered (a valuable lesson in celebrity interviewing; you remember everything, they remember nothing).

Despite the fact he had been ordered to conserve his voice for the stage, we once again talked through the afternoon. Finally, Shirlee poked her head in the door and said in a warning voice, “Fonda, that’s enough.” He shrugged, and we stood to say good-bye.

As I waited down the hall for the elevator, I could hear the Fondas, their voices raised in anger. Shirlee Fonda was not happy that her husband had spent so much time with a reporter. “Shirlee,” Fonda replied sharply. “It’s my job.“

At the end of My Darling Clementine, Henry Fonda as Earp says good-bye to the lovely Clem and then rides off down a long and winding road. I found myself suddenly choked with emotion, not only at the simple beauty of John Ford’s neglected masterpiece, but also by the memory of that long-ago afternoon in Detroit with a legendary movie star doing his job–and doing it so very well.

October 18, 2012

Bad Night In Paris: An Excerpt From The New Tree Callister Novel

Intrepid private eye Tree Callister returns for Another Sanibel Sunset Detective . The novel will be published by West-End Books next month, but it’s available now as an e-book.

Tree is in Paris with his wife Freddie celebrating her birthday. But Freddie has become ill and doesn’t want to go out. Tree decides to return to one of his favorite Parisian haunts for a bite to eat…

Curious how  memory plays its tricks.

memory plays its tricks.

Tree remembered the bistro side of La Closerie des Lilas being much larger than the intimate dark wood ship’s cabin that confronted him. It had been years since he was last here and during that time, Lilas had expanded in his mind to accommodate constantly growing memory.

A friend had brought him for lunch the first time he was in Paris in the early eighties, another of those places that had drawn Tree because it was a Hemingway hangout.

Tonight, with everyone on the terrace enjoying the summer evening, Tree pretty much had the interior of the brasserie to himself. Just him and whatever ghosts of Hemingway lingered. He occupied a stool at the end of the bar near the brass plaque marking the place Hemingway used to sit.

For a moment, Tree was tempted to order a kir royale, his drink of choice in the old days. He dismissed the impulse, asked for sparkling water and a menu. He would eat something at the bar, briefly inhale nostalgia, and then get back to poor, sick Freddie.

“Wait a minute,” he said to the bartender.

“Monsieur.”

“I’ve changed my mind. A kir royale, si’l vous plait.”

Why not? he thought to himself as the bartender nodded and went away. I’m in Paris, after all, and for a single night reliving long-ago youth—a youth that would include a kir royale at La Closerie des Lilas. Or maybe two.

The bartender returned and placed a glass filled with a bright liquid the color of a pale rose on the bar in front of him. Tree stared at it for a time and then lifted the kir royale until it glittered in the light of the Closerie. He placed the edge of the glass to his lips and took a deep swallow.

The sweet, biting taste filled his mouth, and then made its way languidly through his body, as if to warm him with the memory of what it was like to sit here with a few of these inside him. Of course, it was never the first that got you into trouble. It was always the second and then the third.

Well, he thought, putting the unfinished glass back on the bar, he wasn’t going to get into any trouble tonight. Those days were long over.

“You are in my seat,” a voice behind him said.

He turned to find a young woman standing there. He had a sense of blonde hair tumbling around bare shoulders, a short skirt and long legs.

“Is this where you sit?” he said.

“It’s where Hemingway sat, so that’s where I have to sit.”

Tree got off the stool to make room for her, taking his glass with him.

“I’m Cailie Fisk,” she said, offering a slim hand.

He took her hand. “Tree Callister.”

She perched on the stool, very still, closing her eyes as though attempting to draw in the essence of Hemingway. Her eyes popped open again and she looked at him. “I wonder if he really did sit here. I mean, how does anyone really know?”

“I’ve thought the same thing many times.”

“He does talk about the Closerie in A Moveable Feast, so I suppose the chances are pretty good that his elbow must have nudged this part of the bar, however inadvertently.”

“I’m surprised someone your age is even interested in Hemingway.”

“I’m fascinated by all things Paris,” she said. “When you’re growing up in St. Louis, that’s a million miles from Paris, so I embraced all the clichés. The Eiffel Tower. The impressionists. Hemingway in Paris. The unrealistic, romantic view they keep for the tourists. But then I’m the kind of girl who gets to London and rushes over to see the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace. Old things, but enduring. I like that.”

The bartender came over and arched an eyebrow? “Madame?”

She ordered a kir royale.

Tree looked at her. “Why a kir royale?”

“I don’t know. I read somewhere that if you came to La Closerie des Lilas you should order a kir royale. So here I am at the Closerie ordering a kir.”

“That used to be my favorite drink.”

“Used to be?”

“Back in my drinking days in Paris.”

“What’s that you’re holding?”

“It’s a kir royale,” Tree said.

She smiled. “Your drinking days appear to have returned.”

“Nostalgia overcame me for a minute there,” Tree said.

“How did it taste?”

“Not quite the same.”

“It never does, I guess. You came here for work?”

He said, “I was a newspaperman in Chicago.”

“But you’re not anymore?”

“Not for a long time.”

“What do you do now?”

What to say to that? “Now I’m a private investigator on Sanibel Island in Florida.”

“You’re not serious.”

“Some days I wonder,” he said.

The bartender placed the kir royale in front of her. She lifted the glass off the bar. “To Hemingway and nights in Paris,” she said.

He touched his glass to hers. “To Hemingway,” he said.

She took a tentative sip and smiled. “So let me see, Sanibel Island,”

she said. “That’s off the west coast of Florida, isn’t it?”

“That’s right. In fact, the agency I run is called The Sanibel Sunset Detective Agency.”

“And how many agents does Sanibel Sunset Detective employ?”

“Just one,” Tree said.

“You?”

“I’m the Sanibel Sunset detective.”

“I see. Are there many calls for private detectives on Sanibel Island?”

He laughed and shook his head. “Everyone thought I was crazy, including my wife. But there is business as it turns out.”

“You’re in Paris with your wife?”

“Yes, we’re here celebrating her birthday.” Now Tree was beginning to feel embarrassed, and the burning in his face wasn’t just the result of the unexpected liquor in his system. He hastened to awkwardly explain: “She’s come down with some sort of bug. I ducked out to get something to eat.”

“I’m sorry to hear she’s not feeling well,” Cailie said. “I hope she’s going to be all right.”

The waiter returned and asked in English if they wanted menus. “I haven’t eaten anything today and I’m starving. Have you eaten yet?”

“No, not yet,” he said.

“Why not get something together, and then you can get back to your wife, and I’ll go back to my lonely, miserable hotel room.”

Tree thought of Freddie back at their apartment. She probably was sound asleep. And he was hungry, and, he had to admit, the kir royale had released something inside him. He felt loose and free tonight, like the old days in Paris. Why not dinner? He glanced around at the unoccupied tables and booths. “Why don’t we sit over there against the wall?” He turned to the bartender. “Is that all right?”

“Bien sûr, monsieur.”

They took their drinks to the table. Cailie sat facing him and the waiter brought the menus.

“Tell me about yourself,” Tree said. “You grew up in St. Louis. Are you still there?”

She studied the menu a moment before she said, “Very much so.”

“What do you do there?”

“Right now, I’m not so sure.”

“No?”

“It’s the sort of confusion that occurs in a life when your sister is killed, and you break off with your fiancé, and all the things you thought were certain in life suddenly aren’t so certain anymore.”

“I’m sorry,” Tree said.

“Don’t be sorry about the fiancé,” she said. “He’s a jerk. But my sister was a different matter. We weren’t very close, but still, she was my sister. Everyone in the family was devastated, of course. My parents are having a terrible time with it. I had to get away. I’ve always wanted to come to Paris, and so I thought, well, if I’m ever going to do it, then maybe now is the time.”

“And was that a good decision?”

She paused to consider this. “I think so,” she said carefully. “Although it turns out you can’t outrun your demons—or your memories.”

“You certainly can’t outrun your memories,” Tree said. “That’s the trouble with Paris. It holds onto them for you and waits for you to come back and then springs them on you.”

“Maybe,” she said with a shrug. “But I’m a newcomer, remember. So I bring dreams to Paris, not memories. Overall, Paris has been a fine escape. I don’t have to think about my sister here, I don’t have to think about anything but seeing and experiencing all the things I’ve always dreamt about the city.”

“What happened to your sister?” he asked.

Cailie appeared not to have heard the question.

A server arrived and so they ordered: the red mullet filet for him; simple chicken for her, accompanied by a glass of Pouilly Fuissé. He declined wine. The warming effects of the kir were beginning to wear off, leaving him with a slight buzzing in his head. He should never have had that drink. When their meals arrived, they ate pretty much in a silence filled with Gershwin and Cole Porter, and some Henry Mancini, courtesy of the piano player.

By the time they finished, the few diners inside the brasserie had departed. The piano player had closed down for the night. Tree ordered the check, feeling a lot more sober and somewhat relieved: he was enjoying his time with this lovely young woman, but he could not quite shake the guilt he was feeling, thinking of Freddie sick and alone while he dined in style at a fashionable Paris bistro. Now it was ending, and he could get back to Freddie.

When the bill arrived, Cailie insisted she pay. “It’s my treat,” she said. “I was expecting a boring evening all alone in Paris. Then here you are to make things a lot more interesting.”

“I’m not sure how interesting I made them,” Tree said.

“Would you like to do me a favor?”

“Sure, what can I do?”

“Do you mind if we share a taxi?”

“Of course not.” Why wouldn’t he share a taxi, after all? At this time of night, it would be hard enough to get one cab, let alone two.

I’m staying at the Lutetia. Do you know where that is?”

“On Boulevard Raspail. I’ve stayed there many times.”

“If you could drop me off, that would be great.”

To his surprise, they found a taxi waiting outside—his lucky night for cabs in Paris. They were only five minutes away. They rode in silence down the wide boulevard to the hotel. When they pulled up in front, Cailie said, “This is really embarrassing.”

To his surprise, they found a taxi waiting outside—his lucky night for cabs in Paris. They were only five minutes away. They rode in silence down the wide boulevard to the hotel. When they pulled up in front, Cailie said, “This is really embarrassing.”

“What is it?” Tree said.

“The fiancé I was telling you about? I broke it off, like I said, but he’s followed me to Paris.”

“This guy is here?”

She nodded. “That’s why I went to La Closerie des Lilas tonight. He was bothering me, so I jumped in a taxi and, not knowing where else to go, I told the driver to take me there. My fiancé doesn’t know a whole lot about Paris restaurants, so it worked. Would you mind walking me to my hotel room, just in case he’s lurking around.”

“Sure,” Tree said. “But if he’s threatening you, you should go to the police.”

“Well, I’m not particularly anxious to deal with the French police, and it’s just for tonight. I’m flying back to St. Louis tomorrow. Besides, I’ve got the Sanibel Sunset detective with me, so I’ll be all right.”

“I’m not so sure about that,” Tree said. “But let’s get you inside the hotel.”

Tree followed Cailie to the bank of elevators. “I’ll say goodbye here,” he said.

“Humor me, please, Tree,” she said. “Stay with me until I get to my room.”

“All right,” he said. Yes, that was the polite thing to do, he thought. The last few moments in the final act of the production titled Reliving Your Youth—making sure the beautiful young woman got safely to her room.

She smiled her thanks. “It’s probably nothing. But just in case.”

They took the elevator to the sixth floor and stepped into a long corridor done in drab greens and browns. “I was just thinking,” she said. “Maybe you’ll expand your agency. Soon you’ll need another Sanibel Sunset detective.”

“Why? Do you have experience as a detective?”

They reached the door to her room. She inserted a card in the lock, and the little light blinked green, and the door clicked open.

“Sanibel Island sounds intriguing.”

“It’s a unique, lovely island, no question,” Tree said.

He held the door for her and she went through saying, “Come in for a moment.”

He followed her inside. The door hushed shut behind them. He had an impression of two single beds pushed together—a bad habit at the Lutetia, Tree thought—heavy drapes, French doors open to the cooling night air. Cailie Fisk in a blur descended, wrapping her arms around him, her lips anxious to find his mouth, her slim body pressed hard against him.

He was so taken aback that for a moment he did nothing—the telling, damning, weak moment that was to haunt him. Then, realizing what he was doing, or wasn’t doing, he jerked away in the same panicky manner he might have dodged a punch.

“What are you doing?” The words sounded forced and lame.

“It’s Paris,” she said, curiously out of breath.

She reached around, doing something to her blouse. The next thing, to his astonishment, she was naked to the waist. He backed toward the door, turning away from the glowing invitation of her body.

“What’s wrong with you?” she called.

“I’m leaving,” he said.

“You’re what?” Cailie amazed.

He reached the door. Cailie crossed to him, her face twisting into anger. “You fool,” she said. “You stupid fool.”

“I thought I was helping you,” was all he could think to say.

“Get out,” she yelled. “Get out of here!”

He struggled to open the door. She called him more names and then he was outside, the air conditioned silence of the corridor wrapping around him. He took deep breaths, assaulted by conflicting emotions, among them, he had to admit, stirring lust, but also—the detective rising—suspicion. What was a stunning young woman doing coming onto him like that? What was she up to?

He half expected Cailie to come after him. But her door remained closed as he stumbled thankfully into an elevator.

To read more about Another Sanibel Sunset Detective, and download your copy of new new novel, click HERE.

October 3, 2012

The Last Time I Saw Jimmy Hoffa…

The last time I saw Jimmy Hoffa he was okay.

The last time I saw Jimmy Hoffa he was okay.

It was late in the morning, and I left him standing with William F. Buckley Jr. on the floor of a Detroit television studio. What happened after that, I can’t say.

We now know for certain, however, that the former Teamsters boss who disappeared in 1975, is not buried in the backyard of the suburban Detroit home that has been the object of so much attention. Hoffa’s whereabouts have become an American obsession, a kind of continuing urban legend fueled every few years by yet another tip alerting authorities to where he is supposed to be buried.

But that morning Hoffa was still very much alive, and there I was with him and Buckley, then America’s most famous conservative writer and intellectual, as well as Frank Mankiewicz, the former press aide to Robert Kennedy, who was running George McGovern’s campaign for the U.S. presidency against Richard Nixon.

How I ended up with this unlikely trio, well, that’s a story.

In late September of 1972,William Buckley came to Detroit for several episodes of his popular Firing Line talk show aired weekly on Public Television. When I arrived at WTVS, I expected the studio to be full of reporters. To my surprise, it was just Buckley and me. We talked in his dressing room for an hour or so.

He was friendly and relaxed and seemingly in no hurry to end the interview. Two things still stand out from that long ago conversation. The first thing was that Buckley’s shirt collar was frayed. I remember being fascinated by that. Here was a wealthy man, the patrician who attended Yale and moved easily in the higher reaches of American life, and he was about to go on television wearing an old shirt with a frayed collar.

The other thing I remember is the comment he made when I asked him about the most difficult part of his job. “Coming up with an opinion on everything,” he promptly replied. “Some things I don’t care about one way or another, but people still want to know what I think. Then I have to find something to say, when I don’t really have anything at all to say.”

After we finished talking, he invited me into the studio where he was about to tape the day’s shows. When we entered, there was Jimmy Hoffa. I had no idea he was one of the guests, and I remember being shocked at seeing him–he was, after all, one of the most notorious figures in American life, only recently released from a federal prison.

Buckley introduced me and we shook hands. If Hoffa realized I was a reporter, he didn’t seem concerned about it.

We were then joined by Frank Mankiewicz, the former press aide to Senator Robert Kennedy, who not only was present when Kennedy was shot in June 1968, but also announced his death a few days later.

We were then joined by Frank Mankiewicz, the former press aide to Senator Robert Kennedy, who not only was present when Kennedy was shot in June 1968, but also announced his death a few days later.

Here was the irony: as U.S. Attorney General, Bobby Kennedy had hounded Hoffa for years while he consolidated his power and made the International Brotherhood of Teamsters into the largest and most formidable (and some would say crooked) union in the United States. It was Kennedy who put Hoffa in jail, sentenced to eight years for fraud and jury tampering.

As Hoffa was introduced to Mankiewicz that morning, he had been out of prison only a few months, controversially pardoned by President Richard Nixon after serving four years. Now here was Bobby Kennedy’s worst enemy shaking hands with one of his best friends–not to mention the guy trying to defeat Hoffa’s pal Nixon–watched over by a gimlet-eyed Buckley and a young, slightly awe-struck reporter.

Hoffa was big and imposing in a black suit and a white shirt. One look at him and you could understand how a former grocery store clerk could muscle his way to the top of the American labor movement. What particularly impressed me was the size of his hands.They were like ham hocks. You would not want to get hit by one of those hands.

But nobody was hitting anyone that day. What amazed me was how congenial we all were. By now, technical problems had delayed taping, so there we were, the four of us in a semi-circle chatting about this and that, just like old pals.

Hoffa was on Firing Line to discuss, of all things, prison reform. He talked about what had to be done to improve the nation’s prisons while the three of us listened attentively. He was not at all intimidating. If anything, he came across as your blue-collar uncle who had stopped by on his way to a funeral.

All the same, I couldn’t take my eyes off those huge hands. I remember thinking that the day before yesterday I had been trying to explain why I didn’t finish my math homework. Now, here I was talking to Jimmy Hoffa.

Finally, the technical problems were solved and the taping of Firing Line was about to begin (Mankiewicz and Hoffa were appearing in separate segments). I thanked Buckley for his time and he gave me that famous chipmunk grin and went off toward the set. I turned, and there was Hoffa. He took my hand in his ham hock and said, “Nice meeting you, kid.”

That was the last I ever saw of him. A couple of years later he vanished into legend.

But he was okay when I left him.

Honest.

September 25, 2012

James Bond Saved My (Sex) Life

I know exactly what made James Bond so popular when I was a kid fifty years ago.

I know exactly what made James Bond so popular when I was a kid fifty years ago.

Sex.

James Bond was not just the world’s most famous secret agent. He was also the first sexual superhero (the only one, come to think of it). Bond avidly seduced women. And, more to the point, women just as avidly wanted to be seduced by him.

The original movies enthusiastically brought Bond’s sensuality to the big screen. When Dr. No premiered in October, 1962, audiences had never seen anything quite like it (Lawrence of Arabia, The Longest Day,To Kill A Mockingbird, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, were the sort of traditional movies being released that year).

Vanity Fair magazine says watching Dr. No today remains an exhilarating experience, and that is true. However, you should have been a teenager in a small Eastern Ontario town when that movie came out. I had to sneak out of the house to see it. I thought the top of my head was going to come off. Watching the movie for the first time in the Capitol Theatre in downtown Brockville, I could hardly contain my excitement.

Sean Connery, the first (and, of course, the best) Bond, exuded a dark sex appeal that has not been matched on the screen since by anyone, certainly not the five Bonds who followed him.

Sean Connery, the first (and, of course, the best) Bond, exuded a dark sex appeal that has not been matched on the screen since by anyone, certainly not the five Bonds who followed him.

Never mind what anyone tells you, I maintain the single most electrifying moment in the history of sex in the cinema occurs when Ursula Andress as Honey Ryder first appears in a white bikini–Amphitrite, the Greek goddess of the sea, rising out of the Jamaican surf, locked forever into adolescent memory. I would further maintain that no other actress in the history of the Bond franchise comes close to Andress’s astonishing beauty.

The world as I knew it in 1962 was a monochromatic place. There was no sex–except in books and movies. That’s what made the original Ian Fleming novels so thrilling. I discovered Bond thanks to America’s new president, John F. Kennedy, who was a fan. Anything JFK liked, I was bound to like, too.

The first Bond novel I read was Doctor No followed by Casino Royale. I read the books in a tent while my family vacationed in northern New York. But as I devoured the pages, I was no longer in a tent, I was in a casino in France where “the scent and smoke and sweat…are nauseating at three in the morning.”

Europe was an exotic, far away place in those days, but Fleming transported me there, into a world of sophistication previously unknown to a fourteen year old anxious to escape the humdrum world he inhabited. Here was a hero who knew beautiful women, fast cars, good liquor, elegant casinos, and how to navigate the world’s most exotic cities. This was my kind of guy.

The books are much better written than they are usually given credit for these days although in Britain they were attacked for containing “sex, snobbery, and sadism”–all deliciously true: in the novel, Honey is Honeychile Rider and she isn’t wearing the bikini when she emerges from the sea.

In many ways, Ian Fleming was the character he created (the back cover photo on the Signet paperback editions showed him with a cigarette in one hand, a gun in the other). A former World War II spy who had become a journalist, Fleming knew well the world he wrote about–why none of the Fleming surrogates who since have tried to keep the books going were able to recreate the same air of authority or the swift, smart prose.

In many ways, Ian Fleming was the character he created (the back cover photo on the Signet paperback editions showed him with a cigarette in one hand, a gun in the other). A former World War II spy who had become a journalist, Fleming knew well the world he wrote about–why none of the Fleming surrogates who since have tried to keep the books going were able to recreate the same air of authority or the swift, smart prose.

Ironically, Ian Fleming died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-six, on the very weekend I first read Doctor No. I heard the news on the radio, literally as I was finishing the book.

Fleming missed out on his own success. When he died, Goldfinger, the film that sent Bond into the pop culture stratosphere and became the template for the subsequent movies, had yet to be released. He never knew what an enduring phenomenon he had created. Not that he would have thought much of most of the movies, I suspect.

Over the years, I met the two most iconic Bonds. Sean Connery walked into the room bristling with the magnetism and the surly, don’t-give-a-damn attitude that must have originally drawn the producers to him. When he walked out again, he merely had to nod at my then-wife and she melted.

Roger Moore, the longest running Bond, was amiable, and in his mid-fifties, still blandly matinee-idol handsome, a beautifully dressed fellow anxious to sign autographs for the fans.

I never did get used to Moore as a rather vaporous (and eventually much too old) Bond. With Pierce Brosnan, particularly in Goldeneye, I thought they finally had a worthy successor to Connery, but he was defeated by the silliness of the subsequent movies. Brosnan seemed to be in one movie; everyone else appeared to be in something else entirely.

Daniel Craig starred in Casino Royale, arguably the best Bond movie yet made, possibly because the screenwriters went back to the original Fleming novel, discarded the cartoon aspects of previous films and returned our hero to adulthood. But I’m still not certain Craig is Bond in the way Connery was. He’s maybe too thuggish and unpolished, lacking Connery’s sex appeal.

The drab world of my 1960s adolescence has long since disappeared, and along with it the hard-edged sexy Bond that first astonished audiences. Over the years he has been watered down to the point where he was starring in family entertainments–I used to take my kids to Saturday morning previews of the latest Roger Moore Bond. There is a certain irony in the fact that movies made fifty years ago in a supposedly much more conservative time, are sexier and edgier than what is being produced today.

But good Bond or bad Bond, none of it seems to matter. Bond survives inspite of what his gatekeepers do to him. I know lots of people who could care less about, say, Batman. I don’t know anyone who isn’t a James Bond fan.

The love of his adventures is now passed on from generation to generation. I held onto the Bond books I bought as a teenager, and then gave them to my son when he was a teenager, and he loved them. Now his nine-year-old son Josh is a Bond aficionado, who, sometimes to his parents’ chagrin, devours the movies, and knows the James Bond lore inside and out.

And my fascination with Bond continues to this day. As I have been for all the Bond movies, I will be there to see the new Bond, Skyfall, when it opens next month. I couldn’t possibly ignore an old friend who has been so much a part of me for the past fifty years.

After all, in addition to defeating Auric Goldfinger and Dr. Julius No, overcoming SMERSH and SPECTRE, and saving the world countless times, Bond transported a needy teenager out of a drab existence, introduced him to a world of adventure, beautiful women, danger and, most importantly, sex.

You can’t ask much more of an old friend than that. Thanks, 007.

September 12, 2012

I Should Have Known Better: The Wildly Improbable Story of Heavenly Bodies

Last weekend, at the Canadian Film Centre’s annual barbecue in Toronto, I ran into a couple of old friends who, although they didn’t realize it, were unique among the more than two thousand industry types flowing through the old E.P. Taylor estate.

Neither Doug Taylor nor Lawrence Dane know each other, but in their way, they each have had more effect on Canadian film than practically anyone else at the party. Montreal screenwriter Taylor co-wrote Splice, the last homegrown Canadian film to get a major studio release (from Warner Bros. Pictures) in theaters across North America.

Before that, the only other Canadian production to get a similar release from one of the big Hollywood studios was conceived, co-written, and directed by Dane.The movie was Heavenly Bodies, and MGM released it in February, 1984 in over a thousand theatres–the largest release any Canadian production had to that point.

Before that, the only other Canadian production to get a similar release from one of the big Hollywood studios was conceived, co-written, and directed by Dane.The movie was Heavenly Bodies, and MGM released it in February, 1984 in over a thousand theatres–the largest release any Canadian production had to that point.

Heavenly Bodies was supposed to be a mini-budget, quickie TV movie. How it ended up a big MGM release is, as they say, a story–a story I played an often befuddled part in.

It began, as these things tend to, with lunch. I was a freelance magazine writer at the time with a secret yearning to write for the movies – not so secret, actually. I confided it to Larry any number of times. As it turned out, he was an actor with aspirations to be – what else? – a director.

At lunch we decided to collaborate on an idea Larry had about a ruthless paparazzi photographer who gets mixed up with celebrity and murder. To my surprise, we almost immediately optioned the script to a young producer named Robert Lantos, recently relocated from Montreal to Toronto. He and his partner Stephen Roth had offices on either side of a secretary who looked spectacular in a mini-skirt but, in that era of typewriters, could not type.

We no sooner optioned that script, than Larry had another idea: a movie about three young women trying to start up their own workout club, and fighting the big corporate club down the street out to destroy them.

Flashdance, concerning a young woman determined to be a dancer, had become a huge box office hit that was originally written by another Toronto writer, Tom Hedley, a guy we both knew. I thought Larry was nuts– a Flashdance rip-off? Who in the world would be interested in that?

I should have known better.

Despite my best efforts to deter him, Larry pitched the idea to Robert Lantos. Since then, I have sat through countless meetings and lunches with many producers, but to this day I have never seen a producer react to a pitch the way Robert reacted to that one. It was the only time in my life I almost literally saw the light bulb go on over someone’s head.

Soon enough, Larry and I were writing his workout movie together – he had dubbed it Heavenly Bodies, and, for better or worse, that title never changed. What’s more, he convinced Robert to allow him to direct. I could hardly believe it was happening. Every time I turned around, Robert seemed to bring in more co-producers. We met a German who demanded the young women in the film work out with hula hoops. We managed to avoid the hula hoops.

I’m not sure how I felt about any of this other than to feel like an outsider staring in wonder at the strange scene unfolding before me, certain of one thing – this was never going to get made into a movie. Hula hoops or no hula hoops. We were, after all, a couple of guys who barely had been inside a workout club trying to make a movie about young women running a workout club.

I should have known better.

The next thing I knew, I was inside a converted warehouse full of Spandex-clad women in leg-warmers, Larry behind the camera yelling “Action!” Not only was Heavenly Bodies in production but the tiny TV movie soon began to take on big-budget trappings.

The next thing I knew, I was inside a converted warehouse full of Spandex-clad women in leg-warmers, Larry behind the camera yelling “Action!” Not only was Heavenly Bodies in production but the tiny TV movie soon began to take on big-budget trappings.

Playboy became involved, and then Hollywood über producers Peter Guber and Jon Peters. Giorgio Moroder, who had done the score for Flashdance, oversaw creation of the music. Fabled MGM, home to the likes of Clark Gable and Judy Garland, agreed to release the picture (Robert says there is a great story surrounding how he convinced MGM to take the movie, but I have yet to hear it).

Music scenes were reshot to provide more production value (Dane says only one additional sequence was actually filmed). Robert spoke of Heavenly Bodies as a “Cinderella story.” There were predictions the movie would do twelve million dollars on its opening weekend–a huge figure at the time.

There was only problem with all these high-powered producers and big studios and growing expectations–at the end of it all there was still only this minuscule TV movie shot on a shoestring budget (Robert says $900,000). All the talk in the world could not transform the sow’s ear into a silk purse.

That became evident when Heavenly Bodies, starring a then-unknown Cynthia Dale (she has gone on to better things), opened in the midst of a howling blizzard in February, 1984.

And bombed.

Robert, who had so artfully created something out of not much of anything, and pushed the movie higher than anyone ever expected it could go, could not in the end convince an audience to see the movie.

For me, Heavenly Bodies quickly turned into a nightmare. By that time I had become the movie critic for the Toronto Star, Canada’s largest newspaper. Naively, I figured everyone would react to my involvement with an understanding sense of humor.

I should have known better.

You would think I had been defrauding widows and orphans of their life savings the way my fellow critics tore into me.

I remember gathering my family and the dog in front of the television set on the Friday evening Heavenly Bodies opened. Critic Leonard Maltin was reviewing the movie on Entertainment Tonight.

At the end of his lacerating review, his eyes grew large with surprise. “What’s more,” he reported, “it turns out that one of the writers is a movie critic. Well, here’s a piece of advice.” He leaned toward the camera and seemed to speak to me personally: “Don’t give up your day job.” I looked around. Only the dog was still in the room.

In the years that followed, I tried in vain to shake off the shadow of Heavenly Bodies–not helped by the fact that the box office bomb went on to become a huge success on video.

Divorced, fed up with Toronto, and having left the Star, I fled to Los Angeles to finish writing a book – and, in my mind at least, to make a new start. Finally, I had escaped my past. I felt calm and at peace as I settled in that first evening in my new apartment. I turned on the television set and – literally this is true – there on the screen was Heavenly Bodies. I could run but I could not hide from that movie.

Splice is a much better and more ambitious film than Heavenly Bodies. Nonetheless, it suffered a similar box office fate when it was released in the summer of 2009. You hope against hope with these things even when you know you shouldn’t, and when it doesn’t pan out, it’s devastating.

Splice is a much better and more ambitious film than Heavenly Bodies. Nonetheless, it suffered a similar box office fate when it was released in the summer of 2009. You hope against hope with these things even when you know you shouldn’t, and when it doesn’t pan out, it’s devastating.

Despite all the hoopla around the Toronto International Film festival this week, the hard reality is that most Canadian films are lucky to open in one theatre, never mind a thousand.

Given the state of Hollywood, it’s highly unlikely a major studio would ever take a chance on a small Canadian movie like Heavenly Bodies or Splice and give it a wide release.

Meanwhile, Flashdance, the movie that inspired Heavenly Bodies, is headed for the Broadway stage. Can a Heavenly Bodies musical be far behind? I would say that’s impossible.

But then, as I have already demonstrated, I should know better.