Ron Base's Blog, page 16

May 28, 2013

Back To School–Without My Turtleneck

All the more ironic, then, to find myself, nearly fifty years after I had successfully made my escape, back inside the Gulag of my youth.

The Brockville Collegiate Institute (BCI, as we called it) celebrated its one hundred and twenty-fifth anniversary this past weekend. Former students from as far back as the 1940s attended. The students from the 1960s gathered at a riverfront pub Friday night to stare in amazement at each other, hurriedly trying to separate out a sea of (slightly) aged faces framed in gray from the hazy memory of friends last seen nearly half a century ago.

Many of us had managed to bury our youthful identities extraordinarily well.

Although we all had a great time, there were, interestingly enough, a lot of people who, much like me, did not bring particularly fond memories of BCI back to what was supposed to be a celebration of high school years.

Although we all had a great time, there were, interestingly enough, a lot of people who, much like me, did not bring particularly fond memories of BCI back to what was supposed to be a celebration of high school years.

Little wonder. When I was there, the school seemed go out of its way to make classes as boring as possible. Conformity was the order of the day. We marched in single file from class to class. If a male student’s hair was deemed to be too long, he was ordered to get it cut.

The teachers were often downright nasty–the Latin teacher thought nothing of coming up behind miscreant students and slapping the unsuspecting offender across the back of his head (he let the girls pretty much alone).

So rather than breeding a generation of learned academics, the school appears to have turned out escaped prisoners of war, brought back together to talk not of high marks and great feats of athleticism (the Red Rams football team generally put themselves into traction before the season even got under way), but to trade war stories.

I thought at times over the weekend that I was part of a remake of The Great Escape.

I had a hard time finding anyone, myself included, who had even graduated. Yet somehow the attendees appeared to have done pretty well for themselves. The big high school lug became a lawyer. The hot-tempered tough guy became a town planner (although I’m still not so sure I’d want to cross him). The star of the football team back in the day and the head cheerleader got married and are still happily together all these years later (they even graduated).

A visit to the school the next afternoon revealed more reasons why memories of the time served there are not always nostalgic. A new wing has been added, but the original brick structure with its slightly Dickensian workhouse air, still sits fortress-like, frowning down on students and visitors alike–I can’t be sure but I think the building had a particularly deep scowl when I showed up at the door.

A visit to the school the next afternoon revealed more reasons why memories of the time served there are not always nostalgic. A new wing has been added, but the original brick structure with its slightly Dickensian workhouse air, still sits fortress-like, frowning down on students and visitors alike–I can’t be sure but I think the building had a particularly deep scowl when I showed up at the door.

Inside, the brickwork and the lockers sport a fresh coat of paint–done in the school colors of black and red–but otherwise the halls and classrooms are much the same as they were when I was being frog-marched down to the principal’s office.

On a Saturday afternoon, away from the crowds of former students chowing down on hot dogs and hamburgers in the school gym, time here hasn’t quite stopped, but it has slowed enough to give you an eerie sense of finding yourself back fifty years or so in the place where you more or less started.

Not that I knew these halls and classrooms very well–I couldn’t even find my old locker, the one I was closing the day the vice-principal, Mr. Grant, confirmed in that formal voice with which everyone spoke to students (and probably still do), “Yes, I do believe that’s correct. President Kennedy has been assassinated.” As if presidents were gunned down every day.

Like Steve McQueen and company in The Great Escape, my friends and I spent a lot of time figuring ways to get out of this place. We would skip school nearly every Friday afternoon, hire some down-and-out-guy outside a King Street tavern to buy us a case of beer (in those days the legal drinking age was twenty-one; I was seventeen), and then retreat to someone’s place to sit around and drink.

The beer drinking was only part of it; what really counted on those Friday afternoons, was the friendship. Although we weren’t unpopular, none of the Brockville Boys I hung around with felt like they fit in. None of us liked school, principally because nothing about it interested us, and although we weren’t particularly rebels, in our own quiet way we disliked authority, at least not the ask-no-questions-just-obey-orders mentality omnipresent in our lives.

So we skipped school when we shouldn’t, and drank beer when we shouldn’t, and drove to Ogdensburg across the St. Lawrence River in New York State (where the drinking age back then was eighteen), when we shouldn’t. Everything we did, we should not have been doing. Which, of course, was what made it all worth doing.

When we came together this past weekend, all of us now in our sixties, some of us certified senior citizens, most of us grandfathers, we did not talk about what happened at school, we talked about the ways we escaped the things that happened at school. What transpired in these long echoing BCI halls was never very memorable; the ways in which we fled those halls–impossible to forget.

By the time Saturday night rolled around, the reunion was fast running out of gas. Following a standup dinner there was supposed to be the big, gala dance complete with live orchestra to cap off the weekend. But by the time the band started playing, everyone had pretty much disappeared. We are, it turns out, not as young as we used to be.

Time to leave. By then, someone had pointed out to me, probably accurately, that “when you were in high school, no one appreciated your writing more than you did.”

Someone else had announced that they had lost a hundred-dollar bet because I had not shown up at the reunion in a turtleneck–causing me to have nightmares about the number of turtlenecks I must have worn at BCI.

My wife Kathy, who braved the weekend and many oft-repeated stories, all of which seemed to feature me throwing up, wanted to see my ex-girlfriends. But, perhaps wisely on their part, none showed (no sign of Gabrielle, the long-haired girl who broke my high school heart, but then she was from the rival school, and not to be trusted).

Thus I was left with only sweet, fond memories of lovely young women who put up with a tall, gangly, pimply faced kid who had, to say the least, a great deal yet to learn about women (not to mention writing and turtlenecks).

At the end of it, as the Brockville Boys hugged and said goodbye, it struck me again that the BCI reunion had nothing much to do with high school. It had everything to do with enduring friendship. That’s why we were there. Not so much to remember as to reconnect, to keep going together. Back then we relied on one another to get through the hell of high school.

Fifty years later, nothing has changed. Except I don’t wear turtlenecks quite so much.

At least, I don’t think I do.

May 13, 2013

The Ghosts At Their Underwoods

The ghosts are always at their Underwoods now, and I seem to be walking around with a constantly heavy heart in memory of them.

Last week, Greg Quill, old neighbour, friend, Star colleague, and erstwhile screenwriting partner made his exit. This week it is the legendary –and for once the word is used properly–Toronto Sun editor and co-founder, Peter Worthington.

I doubt they knew one another, and more’s the pity: they were both gentle men and I think they would have liked one another. I certainly liked them, and in a newspaper world grown increasingly dull, they were both, in their very different ways, larger-than-life characters who will be sorely missed.

Greg, sweet, bearlike Greg. It must have been yesterday that I was marveling at his tenacious determination to write for The Toronto Star, amazed at his desire to be part of a place that could be, depending on the day, paradise or living hell–leaning far too often toward the living hell.

Greg, sweet, bearlike Greg. It must have been yesterday that I was marveling at his tenacious determination to write for The Toronto Star, amazed at his desire to be part of a place that could be, depending on the day, paradise or living hell–leaning far too often toward the living hell.

But Greg became a part of the Entertainment department for three decades, an imposing presence, intensely focused, taking the job he was doing very seriously. I remember him bursting into the newsroom, on deadline, out of breath, a notebook flopping in his hand, heaving himself into a chair and getting down to work. Most of the rest of us back then were noisily cynical. Greg never raised his voice.

A few years after I left The Star, Greg and I along with his friend, the noted Australian producer David Elfick, decided to write a script. David flew over from his home outside Sydney, and we spent the weeks trying to put a story together.

As with most such projects, the movie never amounted to anything, but I came away from the experience adoring Greg. We spoke for the last time a few months ago, remembering the days with wonderful Elfick, sitting in my apartment, trying–and failing–to make movie magic, having a good, rueful laugh over the whole experience, the craziness of it all, the shattered hopes, the mangled dreams…

The news of Peter Worthington’s death at the age of eighty-six, sent more memories swirling. The news took me back to The Sun newsroom in the Eclipse building on King Street, overlooking Farb’s car wash. The week before I arrived to write for the about-to-be-launched Sunday Sun, Toronto’s first Sunday newspaper, they had gotten rid of the beer machine in the newsroom.

There was no security on the door, so anyone could and did wander in–from would-be Sunshine girls to architect Jack Diamond (who had offices in the building) to journalism students looking for a job (immediately hired in many cases), young actresses looking to be interviewed (welcome Margot Kidder), angry wives gunning for errant husbands. Everyone yelled into a phone. Teletype machines clattered in time with the Underwood typewriters Chaos reigned.

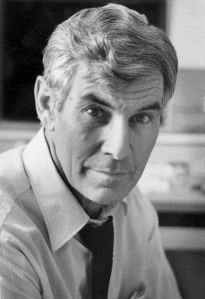

The calm eye in the midst of this ongoing storm was Peter Worthington. Thanks to his days as a globe-trotting foreign correspondent (as they used to be called) for the Toronto Telegram, his was the best-known face in the newsroom–a face camera-ready for newspaper movies about crusading editors: rock jawed, short-cropped hair shot through with grey, piercing, inquisitive eyes.

Despite the fact he was one of the founders of The Sun (along with Doug Creighton and Don Hunt), Peter was surprisingly disarming, frank, charming, and full of mischievous humor, not at all like a guy who owned a big city newspaper.

Despite the fact he was one of the founders of The Sun (along with Doug Creighton and Don Hunt), Peter was surprisingly disarming, frank, charming, and full of mischievous humor, not at all like a guy who owned a big city newspaper.

If anyone kept this wild west of a newsroom together and provided the professionalism that was sometimes (to say the least) lacking, it was Peter. Not for him the lure of Publisher Creighton’s high-end Italian eatery one flight down from the newsroom. The rest of us could go crazy down there–and we often did (cue the reporter peeing into the potted plants)–but not Peter. He could look impishly amazed at the head-shaking antics, but he was never a participant.

Peter was a conservative through and through, but he always struck me as a usually reasonable and articulate conservative–except when it came to Pierre Elliott Trudeau. His daughter, Danielle Crittenden, married the former Bush White House special assistant and political commentator, David Frum. Every time I read Frum or hear him on CNN, he strikes me as the most perceptive and coherent conservative pundit around, and I wonder if a little bit of Peter didn’t rub off on him.

But, my gawd, Peter could be jaw-dropping in his willingness to say out loud anything that crossed his mind. He did not seem to possess–or perhaps had no need for–any of the self-censorship mechanisms the rest of us must employ.When one of the original Sunday Sun editors died, Peter got up to say a few words about him at the editor’s memorial. He fumbled around a bit and then announced he really couldn’t think of anything good to say about the guy because he never much liked him, anyway.

I ran into Peter for the last time about a year ago at an exhibition of new paintings by his longtime friends, Andy Donato (the Sun’s brilliant editorial cartoonist) and his wife, Diane Jackson.

Peter, well into his eighties now, hadn’t changed much from the days when I worked for him in the 1970s: the grey hair was white now, but the jaw remained rock hard, the eyes as piercing as ever–he could still star in that newspaper movie about the crusading editor.

I introduced him to my wife, Kathy, and got him to tell her what I consider one of the most remarkable stories in the annals of Canadian journalism.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, Peter remembered, The Telegram dispatched him to Dallas to cover the tragedy. He arrived in town early Sunday morning.

He told us of how, not knowing quite what else to do, he took a cab to the Dallas Police station. He got out, and there was no one around, so he wandered down a ramp into the police station’s parking garage where a group of reporters and police officers had gathered.

Peter went over to them to find out what was going on. Just then there was a burst of activity, and in came more police officers with a handcuffed Lee Harvey Oswald, the suspect in the Kennedy assassination. As they passed Peter, a man in a grey Fedora stepped out in front of him with a gun in his hand, and shot Oswald.

Peter is immortalized in the background of the still photo seen around the world, reeling back at the moment Jack Ruby guns down Oswald–the Canadian reporter not in town for an hour who had ambled into history.

Peter must have had to tell that story a million times, but I never got tired of hearing it, and he retold it to my wife that evening with the combination of intensity, drama, and offhand charm that he brought to everything.

So I sit here fondly, sadly remembering Greg and Peter and the remarkable characters with whom I’ve been fortunate enough to cross paths. All gone now. Time stops. The past once more is present. The ghosts are at their Underwoods, more real than ever.

May 1, 2013

And Then Ann-Margret Kissed Me…

I have known many publicists over the years, but I have never known a publicist like  Prudence Emery. Wild, wildly lovable, highly intelligent, no-nonsense, a combination gypsy, therapist, drinking buddy, and den mother, I covered more movies with Pru than I care to remember. Together, we turned the moon to blood from Toronto and Montreal to Barkerville in British Columbia and Eilat in Israel. Now, having retreated to Victoria, B.C., Pru is writing a memoir of her movie life. I can’t wait to read it.She’s asked me to contribute memories of our (occasionally) wild times together. Here is my favorite memory–the one for which I am forever grateful to her…

Prudence Emery. Wild, wildly lovable, highly intelligent, no-nonsense, a combination gypsy, therapist, drinking buddy, and den mother, I covered more movies with Pru than I care to remember. Together, we turned the moon to blood from Toronto and Montreal to Barkerville in British Columbia and Eilat in Israel. Now, having retreated to Victoria, B.C., Pru is writing a memoir of her movie life. I can’t wait to read it.She’s asked me to contribute memories of our (occasionally) wild times together. Here is my favorite memory–the one for which I am forever grateful to her…

This is the story of how I came to kiss Ann-Margret. Or, more accurately, I suppose, how Ann-Margret came to kiss me.

It is a story that begins during the long, hot, boring summer of my fifteenth year, on the afternoon I sat in the Capitol Theater in downtown Brockville to see a new movie musical titled State Fair.

I’m not sure why I went to a Rogers and Hammerstein musical that I knew nothing about, other than the fact that it was a movie, and in those days I was willing to see anything that moved on a screen at the end of a darkened room.

State Fair starred Pat Boone, Bobby Darin, and Pamela Tiffin. The plot was simple enough: a Texas farm family attends the annual state fair where brother Pat and sister Pamela learn a few easily digested life lessons in Technicolor with lots of songs, while dad (Tom Ewell) sets out to win a prize for showing his beloved hog (I kid you not; Ewell even sings a song called “Sweet Hog of Mine”).

Sitting alone in the almost deserted Capitol Theater on a sultry summer afternoon, I watched as on the screen innocent Pat (what else could he be?) is introduced to a much more worldly singer-dancer named Emily played by a young (twenty-one at the time) newcomer named Ann-Margret.

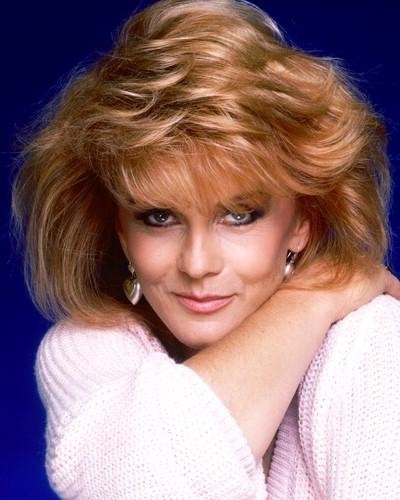

Ann-Margret, I remember, arrived in pale yellow: a yellow polka dot blouse tucked into figure-hugging yellow shorts. She had the most luxurious hair, flame-red, falling past her shoulders, a husky purr of a voice, and the clear face of a slightly decadent angel. The moment she appeared, I was, just like Pat Boone, smitten.

I’ve fallen in love since, mostly in real life, but I have seldom experienced the hit-in-the-gut sensation I experienced that afternoon. My stomach was in knots as I stumbled out of the theater into the sunlight. For the first time in my life–but certainly not the last–I knew the pain of love. Roy Orbison was right. Love hurts.

State Fair played at the Capitol for the next three days. I went back every day and sat through the movie in lovesick agony, impatient to get past the first twenty minutes before Ann-Margret appears.

I bought the soundtrack album and played it so many times on the stereo in the dining room of our house that my poor brother, who, as far as I know, has never seen State Fair and had absolutely no interest in it, nonetheless has the music and lyrics hardwired into his brain to this day.

I was so in love with Ann-Margret that summer I wrote her the only fan letter I ever wrote in my life. She never wrote back. I was devastated.

It was actually her next musical, a screen adaptation of the Broadway hit, Bye Bye Birdie, that made her a star. In the years that followed, I saw her on-screen often, but she never had quite the same effect on me as she had in State Fair. I’ve tried to analyze my feelings about this any number of times. I believe my reaction had something to do with age (of course), with boredom, and with the loneliness of an unhappy teenage boy. It also had a heck of a lot to do with Ann-Margret.

Many years went by, and now I’m an adult, married, living in Toronto, raising two children, and writing magazine pieces for a New York-based syndicate. Prudence Emery, my favorite publicist and a good friend, called to say she was doing PR for a movie shooting in town titled Middle Age Crazy. It starred Bruce Dern. And Ann-Margret.

Ann-Margret? The memories flooded. Pru suggested I come to the set and interview her. I actually hesitated. Ann-Margret was so fixed in the youthful, blissful fantasy land of my mind, that I wasn’t so sure I wanted it ruined by anything as intrusive and heartbreaking as reality. I had long since learned that the best part of movie stars was up there on the screen. The worst part was meeting them in real life.

Still, when you have the chance to meet a dream, how can you resist?

By this time it was 1979, and Ann-Margret was no longer the movie ingénue flirting with Elvis in Viva Las Vegas, playing the Kitten With A Whip sort of roles she was often saddled with in her twenties. In her late thirties now, she was taken seriously as an actress thanks to her Academy Award-nominated performance in Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge.

By this time it was 1979, and Ann-Margret was no longer the movie ingénue flirting with Elvis in Viva Las Vegas, playing the Kitten With A Whip sort of roles she was often saddled with in her twenties. In her late thirties now, she was taken seriously as an actress thanks to her Academy Award-nominated performance in Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge.

Pru introduced us on the set of Middle Age Crazy. I was tense and nervous. She was, well, she was kind of flirtatious, actually. And lots of fun, it turned out. After the day’s shooting, she suggested I meet her and her husband, Roger Smith, back at their downtown hotel suite.

On the way to the hotel, I told Pru the story of my tortured, unrequited teenage love for Ann-Margret. That’s why, I explained, I’m probably acting a little strange. Pru was fascinated. Back at the hotel, she went off to see if Ann-Margret was ready for more conversation.

A few minutes later, I was ushered into the suite and we spent a delightful hour or so chatting–no, that’s not it–that word flirting again comes to mind. She possessed a teasing sense of humor, exuded warmth, and with that slightly breathless, throaty voice, you could easily understand how she drove all the boys wild. You could understand, too, how she might charm a formerly lovesick magazine writer grappling with the fact that fantasy had become reality in a hotel sitting room as evening descended and the shadows shifted.

Finally, it was time to say good-bye. Just the two of us in the room now. We stood and I held out my hand to thank her for a lovely day. She looked at it, and shook her head. “Oh, no,” she said, coming toward me. “Oh, no, no, no.”

The next thing, she put her arms around my neck and drew me down to her, and she kissed me.This was no peck on the cheek; this was a real movie love scene, deep, sensual kiss.

The kid who sat in that small town movie house so many years before yearning to kiss Ann-Margret was–kissing Ann-Margret. Long held movie fantasy momentarily intersected with reality and became–heck it just became great kiss.

Then it was over and she was moving away, eyes twinkling. That throaty laugh, a last squeeze of my hand, and Pru was guiding me down the hall. I floated into the elevator. The teenager kissed by a movie star.”I’ve never seen you like this,” Pru said. I imagine not. I was well and truly shaken.

Then it was over and she was moving away, eyes twinkling. That throaty laugh, a last squeeze of my hand, and Pru was guiding me down the hall. I floated into the elevator. The teenager kissed by a movie star.”I’ve never seen you like this,” Pru said. I imagine not. I was well and truly shaken.

And, of course, it all happened because of wonderful Pru. She had whispered the story to Ann-Margret, and the movie star, seizing the moment, knew how to be a movie star and played the scene superbly.

The years go by and memories fade but that kiss–ah, yes, that kiss lingers.

Thank you, Prudence.

.

April 5, 2013

Lost In The Dark With Roger

Even though I knew the critic Roger Ebert for many years, I actually got lost in the dark at the movies with him only once.

We were sitting around the hospitality suite at the Toronto International Film Festival (or whatever it was called then), getting to know one another and before long, my wife at the time, Lynda, and I were sharing popcorn with him at a screening of a comedy called Continental Divide.

The movie was a failed attempt to turn John Belushi into a romantic lead. It interested Roger because it was set in Chicago where he worked, and featured Belushi as a hard-living reporter, a breed with which the two of us were only too familiar.

Afterwards, we had dinner together. At a time when most critics, myself included, didn’t discuss what they thought about a movie until they published their review, Roger was more than willing to blab on about Continental Divide, a movie we both quite liked as it turned out.

That was the Roger I encountered over the years, a guy without artifice or pretense. I don’t know whether I liked him before we went to the movies together, but I sure like him after that.

He had started out in Chicago, a tough newspaper town if ever there was one, a town that does not suffer pomposity or preening critical pretensions. No matter how famous Roger became–and he became, as has been tirelessly pointed out in his various obituaries, the world’s most famous critic–he never left Chicago, or the newspaper business, and he never lost the sense that the guys in the newsroom would call him out if he got too carried away with himself.

He was close friends over the years with close friends of mine, and I suppose I knew him better through Dusty Cohl, one of the founders of the Toronto Film Festival, and Hans Gerhardt, the legendary hotelier who in those days was running celebrity central at the Sutton Place Hotel.

They adored him, Dusty in particular. And Roger loved Dusty right back. When Dusty started up something called the Floating Film Festival (on a boat, ergo the floating) Roger was there. When Dusty died, and Roger, ill with cancer, could not be at his memorial, he sent his delightful wife, Chaz, to steal the show.

It was Dusty who persuaded Roger to attend Toronto’s fledgling film festival, and it was Roger, along with Hollywood columnist George Christy, who helped put it on the international map. Roger–and George–remained unfailingly loyal to the festival over the years.

The last time I saw Roger, on his final visit to the festival a couple of years ago, we shook hands at the lunch George Christy throws each year at the Four Seasons. Yet again I found myself shaken by the terrible toll his cancer had taken. Most of his jaw was gone, along with the extra pounds that for so many years had differentiated him from his taller, thinner television partner Gene Siskel, and made the two of them such a TV-ready odd couple.

But nothing, not even cancer, could stop him. He published books and a memoir, and continued to crank out movie reviews, blog posts, and even tweets at a furious pace. Most critics begin to despair of the art they are writing about. The great English critic, Kenneth Tynan, eventually felt he had said everything he had to say about the theater and felt lost and at a dead-end.

Pauline Kael, if one is to believe her biographer, Brian Kellow, became disenchanted with the quality of movies in the 1980s and slipped off into bitter retirement. But Roger never stopped loving the movies, and, if anything, became more enthusiastic and less critical.

Right up to the end, he was very much in the main stream. He generally liked what everyone liked, which probably accounted for much of his astonishing popularity. On television he could sound authoritative but he spoke in the plain, unadorned voice of the Everyman at the movies.

One of the other reasons for his immense success, of course, was his partnership with the late Gene Siskel. They were oil and water together and that always lent a tension to their television appearances. After Gene’s death from a brain tumor at the age of fifty-three, Roger mellowed and claimed the two had grown to like, if not love, one another. But I always wondered.

One of the other reasons for his immense success, of course, was his partnership with the late Gene Siskel. They were oil and water together and that always lent a tension to their television appearances. After Gene’s death from a brain tumor at the age of fifty-three, Roger mellowed and claimed the two had grown to like, if not love, one another. But I always wondered.

Off camera and away from a crowd, Gene could be quite likable. But in front of an audience, he suffered the very pomposity Roger spent a lifetime avoiding. Years ago TIFF decided to honor director Martin Scorsese. Siskel and Ebert were dispatched to do an onstage interview with him and with two of his most famous stars, Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro.

The five of them were sitting on stage when the discussion turned to Mean Streets, one of Scorsese’s earliest successes, and the movie which helped establish both Keitel and De Niro. Siskel abruptly turned to Keitel and said something like, “That scene where you and Bob are walking through the door, what were you thinking when you did that?”

Keitel looked at Siskel as though he was crazy. “What the f– do you think I was thinking? I wasn’t thinking anything. I was walking through the f– door.”

That produced, to say the least, an uneasy silence. Roger had gone white with anger. I thought for a moment he was going to kill Gene right there on stage, so naked was his fury. Gene appeared oblivious.

Hearing about Roger’s death yesterday at the age of seventy, I thought of the time at the Cannes Film Festival when we decided to do a joint interview with the actress Ann-Margret. Casually dressed and without much makeup, she met us in her hotel suite overlooking the Mediterranean.

We spent the next hour or so asking the usual movie star questions and getting the usual movie star answers. After the interview, she invited us to have lunch with her in the suite, then excused herself to go and change for the television interviews she was to do that afternoon.

After a few minutes she returned. Now her hair fell softly to her shoulders, framing a perfectly made up face. She had changed from her casual clothes into a yellow top and a short skirt, fitted exactly to the contours of a body one could only describe as breath-taking. Both Roger and were suitably awe-struck.

In that moment, we were no longer critics lost in the dark at the movies, just a couple of fellas at the Cannes Film Festival delighting in the glow of a beautiful woman.

April 4, 2013

Taking Trudeau’s Picture

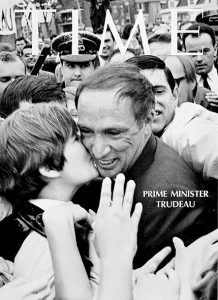

In Donald Brittain’s powerful 1978 television documentary The Champions, about the lifelong battle between Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque for Canada’s destiny, there is a shot of Trudeau being interviewed in the midst of the 1968 Liberal leadership convention.

Trudeau, days away from becoming prime minister, is seated in a glass-walled TV studio in the midst of the convention. The camera pans around delegates and members of the media pressed against the glass for a look at this emerging phenomenon.

The panning camera comes to a stop and briefly focuses on a skinny young man in a trench coat fumbling with a camera.

That skinny guy is me. In grainy black and white. That’s what I was doing forty-five years ago–trying to take Pierre Trudeau’s picture. I must say, I am no better with a camera today than I was way back then.

To my amazement, I found Brittain’s documentary online (at the National Film Board’s web site). I sat watching it on my computer screen, fascinated all over again, not only by my (very) brief appearance but overwhelmed by the realization this marks the forty-fifth anniversary of the convention that forever enshrined Pierre Elliott Trudeau into the lives of Canadians.

Was it really that long ago? Couldn’t be? Could it? The anniversary is also filled with irony, of course, given that the Liberals are about to elect Trudeau’s son Justin as their leader. Once again there is excitement surrounding the promise of someone new and charismatic.

To view scenes from that convention all these years later is to realize with a start how much we have changed in this country and how it all seems so long ago in a barely recognizable black and white galaxy called Canada.

Today, I’m on the verge of becoming an old man, contemplating the end of things, not their beginnings. Back then I was just starting out, everything in front of me, a not-very-enthusiastic student at Ottawa’s Algonquin College journalism school. Somehow, our teacher, a quiet, patient man named Merv Kelly, had scored accreditation for our class at the convention.

I can’t imagine the press today having the kind of unfettered access that we had that weekend at the Ottawa Civic Center. It seems to me we could wander just about anywhere, and rub shoulders with all the candidates, although, in truth, the only one that interested me was Trudeau. I trailed him around everywhere–and he seemed to show up everywhere.

I remember Friday night crowding into the lobby of the Chateau Laurier Hotel in Ottawa where the folk duo of Ian and Sylvia–very popular at the time–was performing live. Suddenly, there was a stirring at the back of the lobby, followed by a wave of excitement as Trudeau appeared unexpectedly and was hoisted through the cheering crowd. If there was security, it wasn’t evident. There seemed to be only Trudeau up on a makeshift podium with Ian and Sylvia, making an impromptu speech, the crowd going crazy.

I remember Friday night crowding into the lobby of the Chateau Laurier Hotel in Ottawa where the folk duo of Ian and Sylvia–very popular at the time–was performing live. Suddenly, there was a stirring at the back of the lobby, followed by a wave of excitement as Trudeau appeared unexpectedly and was hoisted through the cheering crowd. If there was security, it wasn’t evident. There seemed to be only Trudeau up on a makeshift podium with Ian and Sylvia, making an impromptu speech, the crowd going crazy.

None of the other leadership candidates caused anything approaching this kind of excitement. They all seemed old and worn out. Trudeau, on the other hand, was new and exciting. No one had seen anything quite like him; he was a breath of fresh air in what was then such a staid and conservative country.

Anyone who looks back on those times as the good old days probably didn’t have to live through them. It was a mostly all-white society, in many ways still under the colonial shadow of Britain (Canada had achieved its own flag amid much rancor only a couple of years before). The white men who ran the country closed everything up tight on Sundays. You could not even go to a movie.There were still separate tavern entrances for men and women.

If you wanted to buy a bottle of liquor, you went to the government-operated liquor store, filled out a form, signed your name and then took it to the counter and handed it to a clerk who then disappeared behind a partition to reemerge minutes later with your purchase in hand.

Everything was overcooked and bland. There were only a few decent restaurants around and eating out was still considered a special event. In retrospect, Trudeau’s major achievement other than repatriating the constitution from Britain, may have been opening the flood gates to immigration, thereby making it possible to get a good meal in this country.

Books such as Peyton Place, James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer were banned outright in many quarters. In Toronto, people went to jail, literally, for displaying art that was considered pornographic.

The first time I encountered Trudeau, I was still in high school. As just about everyone did in those days, our Brockville Collegiate Institute class came to Ottawa to tour the Parliament buildings–you could just walk in the place back then.

We were supposed to meet with John Matheson, our very popular Liberal member of parliament (probably the last time Brockville ever elected a Liberal). However, Matheson, whom I admired tremendously, was ill that day. He did speak to us over the phone, though, and said he was sending a close friend to substitute for him.

In walked Pierre Trudeau, who was, at the time, Minister of Justice. What did I think of him that day? Was I mesmerized by the man who was soon to lead the country? Not at all. I thought he was boring.

But not at the convention a couple of years later. By then, Trudeau was electrifying the country. Those of us who were part of that time never quite lost our affection for him or forgot the sense of excitement he brought to dull Canadian life. As most Canadian politicians do, he over stayed his welcome, and, as has been very much the case with Barack Obama in the U.S., the reality of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau never quite lived up to the promise of the sports car-driving, movie star-dating young maverick (not so young after all; it turned out Trudeau was forty-eight when he was elected leader of the party).

I won’t be so melodramatic as to say that weekend in Ottawa forty-five years ago changed my life. But certainly my life changed forever that year. A couple of months later, school was behind me, and I was a reporter working for a daily newspaper, The Oshawa Times, while Pierre Trudeau crisscrossed the country in his first election campaign as prime minister, mauled by huge crowds everywhere he went. Trudeaumania was in full flower.

My first day at work I was preparing to cross the street to the Times when I glanced around and saw a lanky, bald-headed man standing on the corner. I realized with a start that this was Robert Stanfield, the leader of what was then called the Progressive Conservative Party, the guy running against Trudeau to be prime minister. I couldn’t believe it. He was all alone, not a soul around him. I went over and shook his hand, understanding at that moment Stanfield didn’t stand a chance in the election. And, of course, he didn’t.

Much has happened since Pierre Trudeau stepped onto the stage that Ottawa weekend, both to me and to the country. Now, as Justin Trudeau is about to become the Liberal leader, I suppose there is a certain closing of the circle.

I wonder if Justin would like his picture taken.

March 29, 2013

Remembering Paul Newman

Paul Newman was handing out popcorn late one cold night on the San Francisco set of The Towering Inferno.

Paul Newman was handing out popcorn late one cold night on the San Francisco set of The Towering Inferno.

The disaster film–the world’s tallest skyscraper is on fire–that was to become 1974′s biggest hit was in its final production stages, shooting in the plaza in front of what was then The Bank of America World Headquarters on California Street.

Newman abruptly burst into view carrying a big bag of the popcorn he had prepared himself in his trailer–the precursor to Newman’s Own popcorn. On a grim set where everyone was freezing and just trying to get through, the gesture lightened the mood considerably.

That was my first encounter with Paul Newman. It would not be my last.

I had flown up to San Francisco from Los Angeles to write about the filming despite a last-minute phone message from the movie’s publicist telling me not to come. I pretended I never got the message and hopped on a plane.

When I showed up, the publicist nearly had a heart attack. However, since I was already there, he had little choice but to allow me to hang around. ”Whatever you do, don’t speak to anyone,” he admonished nervously. That was fine. One did not want to talk, one wanted to watch and listen. After all, this was the most star-studded set I was ever on, and I understood that night I was unlikely to be part of anything like it again any time soon.

Inside the lobby of the Bank of America building, O.J. Simpson wandered past. Outside, William Holden was complaining to director John Guillermin that they were about to do an overhead shot for his climatic sequence that would never be used (it was). Faye Dunaway huddled on the steps to the plaza, ravishing in the evening gown she would wear throughout the movie.

But all eyes were on Steve McQueen and Paul Newman, the biggest names in the picture, and, at the time, the biggest stars in the world. An hour of so after he distributed the popcorn, Newman reappeared strolling around with McQueen who sipped a can of beer. That’s me with them in the photo below–except I’m a few feet off camera.

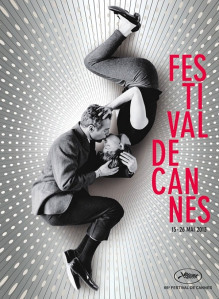

I thought again about that San Francisco night this past week as the Cannes International Film Festival unveiled its 2013 poster. The poster features Paul Newman with his wife Joanne Woodward curled like two commas coming together for a lingering kiss. It’s a fitting tribute, and a reminder not only of the steady glow Newman’s stardom threw off for over forty years but also of a time when there were real stars who made popular, intelligent movies that attracted huge audiences. Those days, to say the least, are long gone.

By the time I met him, Newman had already appeared in such enduring classics as Somebody Up There Likes Me (replacing James Dean, who had died in an auto accident); The Long, Hot Summer (the first time he co-starred in a movie with Joanne Woodward); Cat On A Hot Tin Roof (with Elizabeth Taylor); The Hustler; Sweet Bird of Youth; Hud, Harper, Hombre–his ‘H’ period; Cool Hand Luke; Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting.

For those of us of a certain age, many of these weren’t simply very good films, they were magical markers along the celluloid highway, the man himself the epitome of cool, the blue-eyed sex symbol for generations of movie goers.

When I finally met him he was promoting Absence of Malice, a good thriller about the newspaper business he made with Sally Field, directed by Sydney Pollack, I could not resist asking if he was surprised to find himself the sex symbol still at the age of fifty-five. Newman replied with a rueful smile that he was amazed that it had gone on so long, that everyone hadn’t got tired of it.

But nobody had, and for a long time thereafter, nobody did. Part of Newman’s appeal was his ability to defeat age. From the 1950s into the 1980s, Paul Newman never lost his cool or seemed out of style. Meeting him again and again over the years, he never appeared to gain a pound or take on a wrinkle (he took a sauna every day; maybe that had something to do with it).

He at once knew how to play to his stardom, and how to put it away when it wasn’t needed. He moved around without bodyguards or an entourage. One time I was having lunch in the lounge at the Warwick Hotel in New York. As I got up to pay the bill, there was Newman at the next table, putting on a scarf, getting ready to leave the restaurant, barely noticed by anyone.

He was certainly not gregarious or even particularly outgoing. But he was always courteous, and when you asked him a question he gave you an answer. I remember talking to him for The Verdict, the film directed by Sidney Lumet in which he thought he’d done his best acting, and being surprised at how forthright he was about his own problem drinking over the years.

He was certainly not gregarious or even particularly outgoing. But he was always courteous, and when you asked him a question he gave you an answer. I remember talking to him for The Verdict, the film directed by Sidney Lumet in which he thought he’d done his best acting, and being surprised at how forthright he was about his own problem drinking over the years.

There was much to admire about him. He made great movies, kept a safe distance from Hollywood (in Connecticut and New York), stayed married to the same woman for fifty years, and tried to give as much of his fortune away as he could to various charities. When I asked him about the money, he snapped, “Why not? I don’t need it.”

One of the last times I saw him, ironically enough, was at the Cannes Festival that is honoring him on its poster this year. He was presenting a film version of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie that he had directed. After a press conference with Joanne Woodward, I lingered to watch him as he prepared to leave. He looked paler than I remembered, and for the first time it struck me that even Paul Newman could get old.

Still, when he died in 2008 at the age of eighty-three, it was difficult for me and a lot of others to grasp that he was gone. He had been so much a part of our movie lives for so long, and had looked so damned good up there on the screen, surely death would give him a pass.

But it didn’t.

The memory of him I always carry goes back to that long ago night on The Towering Inferno set. They were preparing to shoot what would be the last scene in the movie: the inferno in the tower finally has been extinguished and Steve McQueen confronts Newman and co-star Faye Dunaway on the steps of the Bank of America plaza.

It was just before dawn and Newman stood illuminated in the darkness at the top of the steps, surrounded by half a dozen attendants and makeup people. They swarmed around, working on various parts of him, spritzing his clothes with water, applying makeup, brushing at his hair.Hud and Harper, Cool Hand Luke and The Sundance Kid, they all stood there in that predawn light, accepting the attention with a studied, slightly amused, stoicism. This was Paul Newman, who he was, what he did.

The movie star at work.

March 20, 2013

“Ron, I didn’t Even Know Rock Was Gay…”

At one point in my (largely) misspent professional life, Doubleday, the New York publishing giant, wanted me to write as-told-to autobiographies. That is, the famous author would tell me the story, and I, the unknown writer, would write it.

At one point in my (largely) misspent professional life, Doubleday, the New York publishing giant, wanted me to write as-told-to autobiographies. That is, the famous author would tell me the story, and I, the unknown writer, would write it.

None of these proposed celebrity projects ever worked out–Robert Mitchum, despite being offered an advance of $1 million for his life story, turned us down flat–but in pursuit of subject matter, I spent some time with the legendary Hollywood movie producer, Ross Hunter.

Hunter is largely forgotten now, but in the 1950s and 1960s he was famous for producing frothy romantic comedies and soapy melodramas, all beautifully shot in pristine Technicolor against opulent settings, featuring the most glamorous stars of the day–the most popular of those stars in Hunter’s fairy tale universe being Rock Hudson.

Hunter is largely forgotten now, but in the 1950s and 1960s he was famous for producing frothy romantic comedies and soapy melodramas, all beautifully shot in pristine Technicolor against opulent settings, featuring the most glamorous stars of the day–the most popular of those stars in Hunter’s fairy tale universe being Rock Hudson.

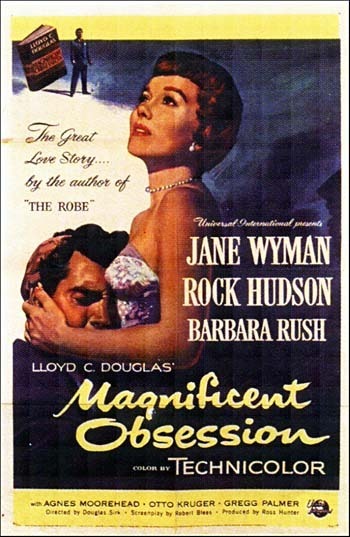

It was Ross who helped catapult Hudson, a former truck driver named Roy Scherer Jr., into stardom after he cast him opposite Jane Wyman in Magnificent Obsession. Thereafter, Hunter produced some of Hudson’s most successful films, including All That Heaven Allows, Battle Hymn, and Pillow Talk, Hudson’s biggest hit, the romantic comedy with Doris Day for which he is best remembered.

I thought about Ross and Hudson the other after the announcement came that a movie is to be made about Rock Hudson or, more to the point, about the invention of Rock Hudson, for he was very much a manufactured studio product, perhaps the last movie star creation–and if not the last, certainly the most successful. They do not make movie stars like Rock Hudson any more, but then they don’t have movie producers like Ross Hunter, either. If Universal, the studio where Ross toiled, was at the time the industry’s bargain basement, Ross always insisted on occupying the penthouse.

Hoping Ross’s life could be turned into a book, I flew to Los Angeles to meet him a couple of years after Hudson’s death in 1985 from AIDS at the age of fifty-nine. Hudson had become the first celebrity to publicly admit to having the disease let alone die because of it, and thus his tragic death had drawn a huge amount of attention.

The former Martin Fuss (everyone in those days seemed to change their names upon arriving in Hollywood) held court at his luxurious home atop one of the Hollywood Hills. Welcoming me as his long-lost friend, waited on by an anxious assistant, Ross was beautifully dressed and brimming with stories about his years as a hit-making producer–stories, I soon discovered, that were carefully dry cleaned and rearranged for public consumption.

For example, Ross would not talk about–or deal with–his own gayness. When it came to Rock Hudson I knew we were in big trouble after Ross announced with a straight face, “Ron, I didn’t even know Rock was gay.”

I looked at him in astonishment before saying something to the effect that it was hard to believe he wouldn’t have known. Hunter swore up and down that he had no idea. Needless to say, with that kind of selective memory, we did not get very far with the book.

Those were the days when stars and movie makers would rather have their fingernails pulled out than admit to being anything but full-blooded heterosexuals. This was particularly true of a ruggedly masculine leading man like Rock Hudson shaped and molded to appeal to women in the sort of carefully constructed romantic melodramas in which Ross Hunter specialized.

To admit anything else, even in the 1980s when by then the world knew of Hudson’s sexuality, apparently remained beyond the pale for Ross. Today, a Ross Hunter probably would have little to worry about. But a Rock Hudson would run into the same problems. The world still likes the illusion of its romantic heroes and action stars as two-fisted ladies’ men.

I had met Rock Hudson in December 1980 as part of the press contingent in New York to cover the premiere of The Mirror Crack’d, what turned out to be the actor’s second last feature film appearance.

The marketing hook for what otherwise was a straight-forward whodunit based on an Agatha Christie mystery featuring Christie’s Mr. Marple character (played by Angela Lansbury), was that a group of 1950s superstars–Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor, Tony Curtis (who had risen through the ranks at Universal alongside Hudson), and Kim Novak–were together for one last big screen swan song. Attention was particularly focused on Hudson and Taylor who were playing husband and wife, and who last had been paired in the classic Giant, the movie that sealed Hudson’s superstardom and for which he earned his only Academy Award nomination.

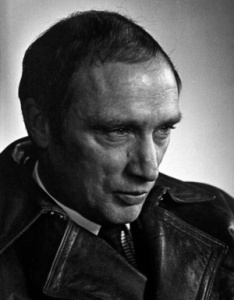

Nobody knew it then, of course, but Hudson had only four years to live. Already age, accompanied by a lot of drinking and smoking, had taken its toll:in his mid-fifties he looked older, gray and puffy.

But he was still a big, strapping guy–at six feet, five inches, he certainly possessed the size and heft everyone expects of a movie star (but seldom gets). It was not hard to see how Ross Hunter, as well as Hudson’s agent Henry Wilson (who changed Roy to Rock after the Rock of Gibraltar) would have seen the leading man getting out of the truck he was driving.

Taylor, Curtis, and Novak had seen better days (although Kim Novak, long retired from movies, still looked stunningly camera ready for the big screen). Nonetheless, they continued to cling to movie star pretensions: flitting around in a swirl of acolytes and publicity people, hurrying away from photographers no longer all that anxious to capture them on film.

Only Hudson hung around, seeming in no hurry to leave. After the din of the various press encounters had died down, he sat at a corner table with a group reporters and chewed the fat about Hollywood and the movies. The biggest male star of the 1950s was, momentarily, just one of the guys.

Only Hudson hung around, seeming in no hurry to leave. After the din of the various press encounters had died down, he sat at a corner table with a group reporters and chewed the fat about Hollywood and the movies. The biggest male star of the 1950s was, momentarily, just one of the guys.

You couldn’t help but like him. He was shy and soft-spoken, and I remember thinking at the time there was an air of sadness about him.

Rock Hudson did tell his story to author Sara Davidson for a book published after his death. In the opening pages, as Hudson is dying, Ross Hunter shows up for lunch and is described as a regular visitor over the years. So he must have known.

Ross died this month in 1996 at the age of seventy-five. He finally told his life story but not to me. I have no idea what he said about Rock Hudson.

But I can just imagine.

February 12, 2013

Marlon Will Love It: My (Hollywood) Life. Part One.

The arrival of the annual Vanity Fair magazine Hollywood edition and the constant drumbeat of Academy Awards season always takes me back to that galaxy so far far away from where I live now–Los Angeles and my so-called Hollywood years.

This year Vanity Fair features a story about the days in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when, as the article reports, “the spec script was king.” This was a time when a writer could sit down at his word processor, hammer out an original screenplay on speculation — the “spec” script–turn it over to his agent who would then auction it off to the major studios anxious to bid hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of dollars in order to acquire it.

I happened to be Los Angeles during that time, working on a book and living in an apartment on North Palm Drive in Beverly Hills, inevitably sucked into the maddening, frustrating whirlwind of screenplay writing that appeared to involve every single resident of the city.

The Vanity Fair piece makes it sound like everyone with a word processor was raking in a fortune writing screenplays, but, as is usually the case, those rewards were reserved for the very few at the very top of the pyramid. Even in those days, L.A. was reminiscent of Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust. The locusts existed at the bottom of the pyramid, scrambling for the crumbs dropped from above.

I was one of the locusts, albeit a fairly comfortable one, lodged in my Beverly Hills apartment, drifting around Los Angeles, forever intrigued by its curious rhythms and strange rituals, always amazed that a kid from small town Ontario was actually driving along Sunset Boulevard.

I wrote a lot of scripts during my time in L.A., but no one ever paid me hundreds of thousands for one of them, let alone millions. If anything, everyone seemed to go out of their way to avoid at all costs paying one single cent for any screenplay of mine.

In fact, getting anyone’s attention at all was an often exasperating and head-scratching experience. Nobody seemed interested in what you wrote, let alone willing to pay for it. And if on rare occasions, there was interest, it was fleeting and would often take the most bizarre turns, leaving you more confused than ever.

One day my agent telephoned, uncharacteristically excited. He had just received a call from the people at Lightstorm, James Cameron’s production company. Cameron, of course, was the guy who had created The Terminator. He was BIG. This was BIG. Cameron’s people had read a script of mine. They wanted to meet me.

I drove out to Santa Monica where Lightstorm had its offices. When I got there, I was greeted eagerly by a young assistant and whisked into a conference room full of more young people. There was no sign of James Cameron.

I drove out to Santa Monica where Lightstorm had its offices. When I got there, I was greeted eagerly by a young assistant and whisked into a conference room full of more young people. There was no sign of James Cameron.

Immediately, the Lightstorm boys and girls broke into smiles and began to express unending enthusiasm for my screenplay. They read so much crap. This was great; the best thing they had read for a long time.

I, of course, lapped all this up. Yeah, I began to think, the screenplay was great. I had finally arrived in Hollywood.These bright young things truly understood my genius.

This all went on for quite some time. I relaxed into the general conversation. These were my new pals–so passionate! So intelligent! They wanted to know about my background. They wanted to know about other projects I was working on. After a while I began to realize the conversation, as congenial as it was, wasn’t going anywhere. There didn’t seem to be any point to this, other than a group of people with nothing much else to do, sitting around, shooting the breeze.

Finally, I summoned my courage and asked if there was any interest in perhaps producing my adored script at Lightstorm. Immediately, the smiles disappeared. The room went silent. They looked at me as if I had landed from another planet.

Eventually, the assistant who had greeted me at the door, shook his head and forced a smile. “Jim only does his own projects,” he pronounced. He would not be interested in doing someone else’s work, the assistant went on. They just liked my script and wanted to meet me.

The meeting was over.

I reeled out into the bright Santa Monica sunlight, stunned and amazed that anyone would want to waste the morning talking to a writer about a script they were never in a million years going to make.

Welcome to Hollywood, I thought, as I dejectedly drove home. Well, lesson learned. I wouldn’t fall for that again.

A couple of years later, an L.A.-based production company, Finnegan-Pinchuk, became interested in another script I had written, hoping to do it as a television movie. Just when it seemed nothing was ever going to happen to the script, I received a call from one of the company’s partners, a likable veteran of the movie and TV wars named Shel Pinchuk.

Shel never got excited about much of anything, but this time I detected a note of enthusiasm in his voice. ICM, the second largest talent agency in Hollywood, had read the script, and they wanted to meet with us.

ICM was then housed in an impressive jade and glass building on Wilshire Boulevard. What struck me about the place as an assistant led us through its interior was the number of scripts everywhere. They were arranged on shelves, piled, literally, to the ceiling–and these were just the scripts that had made it into the hallowed confines of a big Hollywood agency. I began to have trouble swallowing.

We were ushered into a large conference room. If there was one agent seated at the table, there must have been ten, all of them young, beautifully dressed, and hugely–here’s that word again–enthusiastic. They had all read my script–one of the best they had read in a long time. Fantastic! Extraordinary! They were anxious to package it, an industry euphemism for putting a star, a script, and a director together using agency talent and then taking it out to the studios.

The names of ICM stars were bandied about, including, as I remember, Michael Caine. Then one of the agents snapped his fingers, his face lighting up. “You know who would be perfect for this? Brando!” Immediately a loud chorus of approval went up.

I looked around the room in astonishment, and then said something stupid like, “You mean Marlon Brando?” Everyone nodded. ICM had just signed him. He was looking for projects. This would be perfect for him. “But it’s television,” I managed to say. That was dismissed with a hand wave. Marlon would love it.

Eventually, amid much back-slapping and handshakes, we floated out of the conference room. When we got on the elevator, there stood actor Robert Blake, who had starred in TV’s Baretta (this was long before he was convicted of killing his wife).The elevator was made of glass and as it dropped down toward the lobby,we all stared out onto a courtyard surrounded by glass-fronted ICM offices. Blake shook his head. “Just think,” he said. “This whole f–ing place is full of agents.”

When we reached the street, night was falling. I was in a state of euphoria. Even Shel appeared pleased. This was it. I was on my way in Hollywood. I truly was a genius. It was a matter of time before Brando and I became best pals.

We never heard from ICM again.

Shel Pinchuk tried repeatedly to get someone on the phone. But no one ever returned his calls.

January 2, 2013

Hitchcock: The Gentleman Prefers Blondes

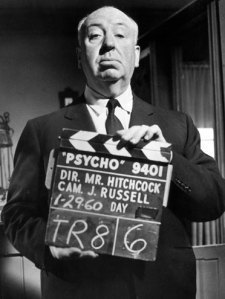

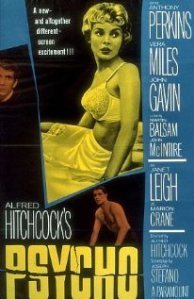

I never met Alfred Hitchcock, but I did interview Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh about the making of Psycho, the seminal thriller for which both actors are best remembered, and which is currently the subject of a breathtakingly wrong-headed and erroneous movie.

I never met Alfred Hitchcock, but I did interview Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh about the making of Psycho, the seminal thriller for which both actors are best remembered, and which is currently the subject of a breathtakingly wrong-headed and erroneous movie.

Hitchcock, starring Anthony Hopkins, is one of two films about the legendary director currently on display. A cable television movie, The Girl, deals with Hitchcock’s tumultuous relationship with actress Tippi Hedren who appeared in The Birds and Marnie.

Hitchcock, starring Anthony Hopkins, is one of two films about the legendary director currently on display. A cable television movie, The Girl, deals with Hitchcock’s tumultuous relationship with actress Tippi Hedren who appeared in The Birds and Marnie.

What’s remarkable, is the fascination Hitchcock still holds for us nearly thirty-three years after his death at the age of eighty. Is the rotund little Englishman who never attempted anything in his fifty-three films beyond keeping the audience riveted to the screen, the most influential director in the history of film? How could he be anything else? Certainly he is the best remembered, as the two Hitchcock movies demonstrate.

But it is how the movie Hitchcock in particular remembers its subject that is the problem. The film supposedly is based on Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, Stephen Rebello’s straight-forward account, published in 1990, of how the director at the age of sixty made the masterpiece that, for better or worse, did more to shape the making of movies than any other film with the possible exception of Citizen Kane. After the release of Psycho in 1960, American movies were never again the same.

Having read Rebello’s book years ago, I was surprised when it was announced a movie would be based on it. The actual making of Psycho was not exactly the stuff of great drama. Hitchcock read the Robert Bloch novel, inspired by accounts of a real life serial killer named Ed Gein, was intrigued, and decided it would be his followup to the immense success of North By Northwest–another Hitchcock classic.

No question, Hitchcock was looking to do something different, away from the big, glossy studio productions he had become so well-known for. He wanted something with a little more edge to it, that showed everyone he was in step with, if not ahead of, the times.

Hitchcock was as powerful in his day as Steven Spielberg is today–if he wanted to do something no one was going to stop him, even if, as was the case, Paramount, the studio to whom he owed one more picture, was not happy.

When the studio balked at the subject matter, Hitchcock decided to do it on the cheap, shooting in black and white, using the crew that shot his hit television series, with money he raised himself.

Even though Paramount finally agreed to release Psycho, the movie was actually shot at Universal Studios–that’s how Norman Bates’s house ended up on the Universal lot, where I first saw it back in the mid-seventies, and where it still sits today, a hugely popular tourist attraction.

Joseph Stefano, who wrote the screenplay for Psycho (and who only gets one scene in the movie), always maintained that the movie was no big deal for a director who by 1959 had been shooting movies for over thirty years.

“Hitchcock didn’t think he was doing anything that was any different from his last movie or would be from his next,” Stefano recalled to author Rebello. “I don’t think at any time he was making it he was knowingly or unconsciously reflecting any particular darkness from within. He simply had a script and he was shooting it.”

The Hitchcock movie ignores this, of course, and shows him worried about age, obsessively dreaming about Ed Gein, and giving the eye to every woman with blond hair who crosses his path.

The Hitchcock movie ignores this, of course, and shows him worried about age, obsessively dreaming about Ed Gein, and giving the eye to every woman with blond hair who crosses his path.

It does get some things right–Paramount’s dislike of Psycho, the censorship problems–but in attempting to work up dramatic conflict the movie runs wildly off the track by supposing that Hitch’s wife, Alma (played by a miscast Helen Mirren), jealous of her husband’s eye for his leading ladies, becomes involved with a cad of a Hollywood screenwriter named–hang on to your typewriter–Whitfield Cook.

As played by the actor Danny Huston (director John’s son), Whit, as he is known, is your typical writer: handsome, sophisticated, urbane–so of course he never existed, except in the cliché-ridden mind of Hitchcock’s screenwriter, John McLaughlin. In McLaughlin’s re-imagining of things, Whit uses Alma’s infatuation with him so that Alma will persuade Hitch to film his script, Taxi To Dubrovnik.

None of this is remotely true, of course, and dramatically it never rises above the trite and boring, and has nothing to do with the making of Psycho. Also, it is highly unlikely that Alma, as the movie insists,pitched in at the end of filming to help save the movie in the editing room.

There is no evidence in Rebello’s book that Alma played any part in the editing of the film (that was done by George Tomasini). In fact, if anything saved Psycho–or at least helped shape it into the masterpiece it has become–it was the addition of Bernard Hermann’s innovative, shrieking violin-filled score.

Poor Hitch. Here he is, the most famous director in the history of film, and he continues to be saddled with all this blonde obsession stuff. It started with Donald Spoto’s biography, The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock, published three years after the director’s death. Spoto laid out the argument that has haunted Hitch’s legacy –and is the basis for the two movies–that he was so crazy about blonde actresses that it almost destroyed him. Never mind that he was somehow able to keep his hands off his most beautiful and alluring blond creation, Grace Kelly (who first appeared for Hitchcock in Dial “M” For Murder).

Tippi Hedren, has been vocal about how Hitchcock ruined her career because she rejected his advances during the making of The Birds and Marnie. There is no reason to disbelieve her account of what happened–in The Girl, she is played by Sienna Miller, and Hedren herself acted as a consultant.

It’s hard to know what to make of her claims. On the one hand, Hitchcock was an all-powerful director in a time of rampant male chauvinism. On the other hand, Tippi Hedren was not exactly the Meryl Streep of the era, and it is questionable whether there would have been much of a future for her as a leading lady even if Hitchcock hadn’t turned against her.

In the Hollywood of the day, when Twentieth Century Fox studio boss Darryl Zanuck would shut down his office every afternoon at four o’clock so that he could have sex with a different woman, Hitchcock seems like pretty small potatoes in the unwanted sexual advances department.

He remained married to Alma for over fifty years, was a devoted family man, dotting father to daughter Patricia, and despite his decidedly inappropriate behavior with Hedren, none of Hitchcock’s many biographers accuse him of actual infidelity. In the Hollywood of his time that makes him, to say the least, unique.

When I asked Janet Leigh, many years after she shot Psycho, about Hitchcock’s so-called blonde obsession, she insisted that as far as she was concerned, Hitchcock was nothing but friendly and helpful (the one good thing about Hitchcock, the movie, is Scarlett Johansson’s portrayal of Leigh). Perkins was downright dismissive when I brought up the subject to him.

When I asked Janet Leigh, many years after she shot Psycho, about Hitchcock’s so-called blonde obsession, she insisted that as far as she was concerned, Hitchcock was nothing but friendly and helpful (the one good thing about Hitchcock, the movie, is Scarlett Johansson’s portrayal of Leigh). Perkins was downright dismissive when I brought up the subject to him.

But in the gossipy culture of our time, Hitchcock is bound to forever remain the cherubic genius fixated on beautiful blondes. As for the films themselves, a recently released, handsomely mounted Blu-ray collection of fifteen of his best-known works, including Vertigo, Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, North By Northwest, and, of course, Psycho, produces a confusion of reactions, ranging from admiration for his undeniable and occasionally innovative skills, to head-shaking at the needless artificiality that dates many of his movies (The Man Who Knew Too Much being a prime example).

I didn’t see Psycho until eight years after its original release, and the film scared me in ways that no other movie has ever scared me. Despite the hundreds of imitations it has spawned, the millions of words devoted to every scene and camera move so that none of the secrets Hitchcock originally went to such lengths to preserve are secrets any longer, viewed today in impressively sharp high-definition black and white, Psycho continues to hold you in its thrall and darkly entertain.

Now there is about to be a new TV series, The Bates Motel, that deals with Norman Bates’s teenage years.What’s more, the British film journal, Sight and Sound, recently polled critics around the world, and they named Hitchcock’s 1957 Vertigo the best film of all time, displacing long time first place holder, Citizen Kane– a development that frankly baffles this former movie critic. .

But there you go. The world continues to be enthralled by a gentleman who prefers blondes.

December 21, 2012

Standing In Airports, Holding A Book, Listening To Stories

This week a reader of The Sanibel Sunset Detective novels e-mailed me several questions, ending with this one: “Why does a man with ten published books to his credit spend his time hawking a handful of them in an airport?”

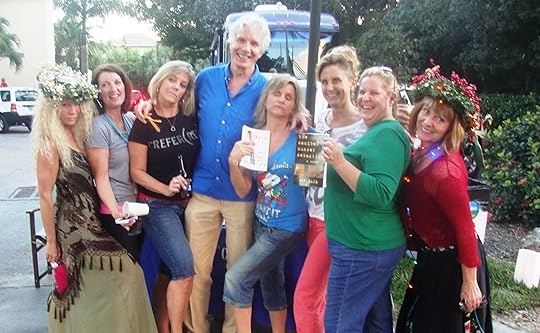

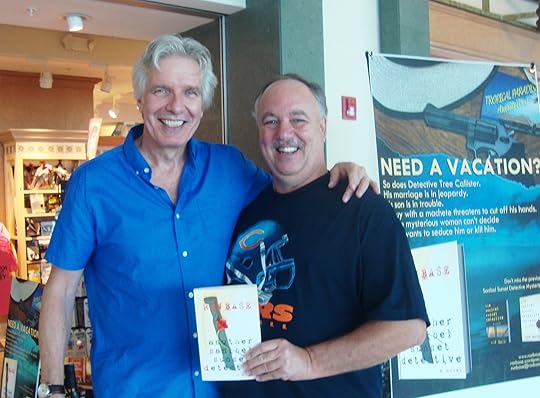

That’s a question I have asked myself more than once, although my question usually includes the word “crazy”. The reader doesn’t know the half of it. I end up in the most unlikely places hawking the three Sanibel Sunset Detective books, not only in airports, but supermarkets, in front of restaurants, even at a farmer’s market. I have sold books at parties and family gatherings.

Every time a new novel is published, I hold a launch party at my home in Milton, Ontario where the neighbors are coerced into coming around for a glass of wine and the opportunity to purchase a new Tree Callister adventure. I host another book launch in Toronto, usually at P.J. O’Brien’s Irish Pub, and I invite everyone I have ever known. I have even been known to darken the inside of a bookstore from time to time.

If anyone had told me twenty years ago that someday I would be doing all these things, I would never have believed it. I was an “author.” I was above such crass behavior. But the times have changed, and this is what you have to do to sell a book now. You must be fearless–or crazy, depending on your point of view.

If anyone had told me twenty years ago that someday I would be doing all these things, I would never have believed it. I was an “author.” I was above such crass behavior. But the times have changed, and this is what you have to do to sell a book now. You must be fearless–or crazy, depending on your point of view.

What all this snake oil selling does, however, is bring the author–me–in direct contact with the one person he should be out there talking to: the reader. Standing in the most unlikely places with a hopeful grin on my face and a book in my hand, I end up meeting the most fascinating people.

And they tell me stories.

With A Swiss Reader

A bearded man is on his way home to care for his dying wife. We end up embracing in the middle of an airport concourse. A woman has just buried her mother. I have some idea what she is going through. We both brush away tears.

Another woman with dramatic gray hair relates in detail how she must care for her ill mother in a tiny house where they fight all the time. She is at her wit’s end and has had to escape.

A fellow named Les stops by to purchase a book and tell me how he sells used clothing on the Internet for a living. He has developed a growing list of clients. He is particularly adept at finding rare ties . A beautifully coiffed woman, impeccably tailored, is a self-help guru who belongs to something called The Creative Thinking Association of America. She does not ask me to join–but she does buy a book.

Another woman tells me an incredible story about her German mother who hated Hitler and so fled to France intending to marry one man, ending up marrying another–and accused of being a Nazi spy.

A Cambridge graduate, whose mother was also sent out of Germany, tells me an equally incredible story about other anti-Nazi Germans who left their homeland and ended up on, of all places, the Galapagos Islands. There have even been a couple of books written about this little known aspect of World War II–the titles of which, as promised, are e-mailed to me.

The stories are endless: the mom with a son in Hollywood working on a TV comedy, a daughter struggling to be an actress; the American businessman who has just arrived on Sanibel Island after moving from Shanghai with his Chinese wife. The beautiful Chicago prosecutor headed home with her child; two federal agents on their way out of town to question a suspect; a customs and immigration officer complaining that government cutbacks are compromising her ability to properly do her job.

One of the first women ever to work in the Ford assembly plant in Windsor, Ontario tells me that when she started in the early seventies, they put her down in a pit in the foundry shoveling sand. She stuck it out for twenty-nine years and saw women become an accepted part of the work force.

A cousin of James Patterson stops to say hello. As Patterson’s cousin, I offer, you must read all his books. Well, replies the cousin, he used to but not any more. Ever since Patterson began collaborating with all those other writers, he finds the novels boring.

Various authors, would-be authors, self-published authors, the mothers and fathers of authors and would-be authors are encountered. Sometimes you get the impression there are more people trying to write books than there are readers reading them.Everyone who is not published wants to know how to be published. Everyone who is published laments the fact and groans about the difficulties.

All of this is so far beyond anything I ever imagined, the encounters with potential readers often so charged with humor and emotion that sometimes I forget that I’m out there promoting the books and end up just going with the flow, taking it all in with a combination of astonishment and pleasure, not so much the writer, more the therapist, sounding board, the sympathetic shoulder upon which you can cry.

Gina With Ron at the Lighthouse Restaurant

In the old days, an author flew from city to city to do media interviews, going from TV to radio station to local newspaper newsroom. Occasionally, the author would stop at a bookstore and sit behind a table signing books. The interaction with readers was minimal at best. When I started writing books in the 1980s, I don’t think I ever met a reader. I certainly never heard from any.

Now I am in the trenches daily, meeting readers first hand, getting their e-mail responses once they have read one of the books. It is both scary and exhilarating. Much like the reader who e-mailed me, I sometimes wonder what the hell I’m doing with my life, and that I must be–here’s that word again–crazy to be doing this.

But then someone comes along, and there is another story, another fascinating encounter, and bless their heart, that person read your last book and loved it and can’t wait to read the next–and suddenly you would not want to be anywhere else in the world, and this is better than anything you’ve ever done.

And every once in a while you even sell a book.

Ron’s latest novel, Another Sanibel Sunset Detective, is available on Amazon and at Barnes and Noble.