Ron Base's Blog, page 15

September 12, 2013

Goodbye To All That: Reflections On An Ending Summer and Chicken Pot Pie

There will be no more chicken pot pie.The summer of things ending–has ended.

There will be no more chicken pot pie.The summer of things ending–has ended.

I know it’s over because the Toronto Film Festival concludes this weekend. From here on in it’s downhill to bleak winter. So as the weekend approaches, I’m consumed with thoughts of what won’t be coming back.

The losses have mounted up over the past couple of months: Dog Clinton, still intensely mourned; close friend and noted theatre and food critic, Gina Mallet; former work colleague and neighbor, Greg Quill; old boss and Toronto Sun co-founder Peter Worthington; the world’s best movie critic, Roger Ebert. All gone.

Even George Christy, the legendary Hollywood columnist, has left the building. Well, left the hotel, anyway. And he’s taken the chicken pot pie with him.

George is still with us, thank goodness, but after presiding over it for thirty years, this week he hosted his last luncheon at the new Four Seasons Hotel. We ate chicken pot pie, and George said what we all were suspecting he would say–that it was time to move on. He would not be coming back next year.

Much has changed at TIFF since I started attending, but one of the surviving festival traditions has always been George’s lunch, a command performance over the years for local movers and shakers, visiting movie stars, and occasional rogue guests like me who George seems to invite year after year simply because he likes us.

George and I actually got off on the wrong foot. About the second year he hosted the lunch, he invited me–and I never showed up. Dusty Cohl, co-founder of the festival, was beside himself. How could I possibly have gone AWOL at George’s lunch? When Dusty was beside himself, one had no choice but to listen.

Thus I hurried to George, apologized profusely, and we have been friends ever since. One thing about George, he sticks by his friends, so despite our rocky start, and my total lack of any importance, I still get my annual invite.

I go back far enough that I can remember when the reception before the lunch was just a group of us standing around in the foyer fronting the Four Seasons dining room, chatting with visiting guests like Hume Cronyn and Dennis Hopper, pals together–at least for an hour or so.

All these years later, that casual reception has mushroomed into a huge cocktail party, an invitation to which is almost as coveted as an invite to the lunch–although the party now fills with young people, most of whom I can’t imagine George knows.

But the rituals of the lunch itself remained carved in (George’s) stone, as formalized as a piece of Kabuki theatre–except a lot more fun. He carefully chose the seating for the hundred or so invitees. Your table and your seat at that table could not be tampered with. Years ago, a newspaper columnist tried to change her seat and was immediately banished.

Over the course of the luncheons, I’ve found myself rubbing shoulders with Jodie Foster (tiny, remote, not very communicative), Helena Bonham Carter (tiny, remote, not very communicative–maybe it’s me), Swoosie Kurtz (delightful), and The Six Million Dollar Man’s sidekick, Richard Jordan (great fun).

Again, I go back far enough that I can remember when chicken pot pie was not always served, and George spent many hours agonizing over the menu. More recently, the chicken pot pie, from a recipe by Toronto impresario Garth Drabinksy, has become de rigueur. As chicken pot pie goes, it is great chicken pot pie.

But all of that is finished now; the Kabuki theatre played out over three decades has closed. We have eaten our last chicken pot pie. George has exited, a trifle reluctantly I suspect, but with the intrinsic sense of a clever ring master who knows his circus and understands it is always better to leave ‘em wanting more.

At the cocktail party before the lunch, I instinctively looked around for Roger Ebert. Even after the cancer that would have stopped anyone else, he still attended with his wife, Chaz. But not this year. This year there was no Roger. More losses.

At the cocktail party before the lunch, I instinctively looked around for Roger Ebert. Even after the cancer that would have stopped anyone else, he still attended with his wife, Chaz. But not this year. This year there was no Roger. More losses.

Chaz and I met at the Canadian Film Centre’s barbecue hosted by director Norman Jewison. We traded Roger and Dusty Cohl stories. It was Dusty, with his trademark cowboy hat and cigar, who first seduced Roger and convinced him to attend the fledgling Toronto film festival, thus helping to put it on the international map. Dusty died in 2008, but he and Roger remained close friends to the end.

I’d met Chaz several times, but until the barbecue never had the opportunity to spend time with her. She is–as has been widely advertised– an absolute delight. When she wants to meet someone, she walks straight up to them, holds out her hand, and introduces herself.

Despite the sadness of Roger’s death, she possesses a wonderful knack for making you feel good about life–or at least a bit more optimistic. So last night, in pursuit of getting on with it after a summer of sadness, I found myself in downtown Toronto celebrating the publication of my old friend David Gilmour’s new novel titled Extraordinary.

There, amid a houseful of people I didn’t know, was David in all his literary glory. Somehow the sight of him holding forth amid the madding crowd made me feel better. We have been friends since we both yelled and screamed about what we thought of movies, David for the CBC, me for The Toronto Star.

We are both about the same age and the same height, with (now) the same hair color. When I was single, a few good words from David got me through the horrors of various floundering relationships (“Hey, you’re a whole lot more interesting than she is, anyway”).

David’s novels are filled with an honesty that is sometimes frightening (at least for men), often very funny, and as close to documentary as any novelist dares to get.Extraordinary is about death and the passage of time–subjects that are right up my alley these days. Sally, the novel’s wheelchair-bound heroine, has had enough and has decided to end it with a little help from the novel’s narrator.

But David, thankfully, hasn’t given up yet. His life once again is in disarray, but as always, he maintains his sense of humor and keeps going. Distracted by the beckoning throng, he quickly autographs a book. We embrace and he plunges back into the fray. My wife and I drift off along the street through the humid evening, suddenly feeling pretty good about life, off to dinner to celebrate nineteen years of blissful togetherness.

So we go on as the summer closes. We haven’t yet had enough. We endure. Despite the losses and without the chicken pot pie.

August 22, 2013

That Summer Lost In Rome

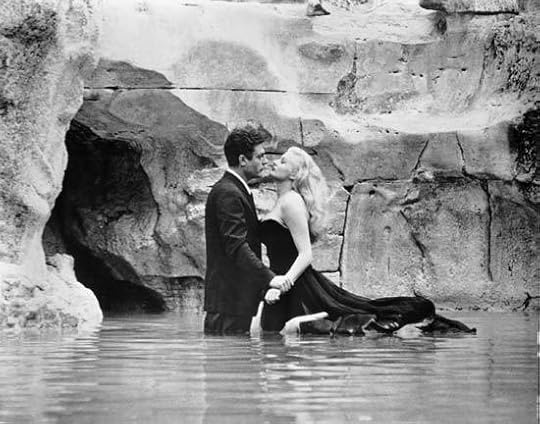

The apartment opened onto a view of Rome’s storied Via Veneto. As I stood staring down at the street, the Italian producer said, “Where you are standing now, this is the very spot where my friend Fellini stood when he decided to make a movie about the Via Veneto called La Dolce Vita.”

The apartment opened onto a view of Rome’s storied Via Veneto. As I stood staring down at the street, the Italian producer said, “Where you are standing now, this is the very spot where my friend Fellini stood when he decided to make a movie about the Via Veneto called La Dolce Vita.”

If the Italian producer was trying to impress me, he succeeded. He was a tiny gnome who had been making movies in Italy since the 1960s. He must have been in his seventies at this point, but he was not giving in to age. He dyed his hair jet black, and whenever he appeared in public, he always had a beautiful young woman on his arm.

The producer was courteous, but he made sure I had no doubts as to his experience and importance. I, on the other hand, was merely another writer in a long line that had been marched in to try to fashion a script from Marguerite Yourcenar’s classic novel of the Roman emperor Hadrian, Memoirs of Hadrian.

Hadrian was the guy who gave the world Hadrian’s Wall in Britain and the Pantheon in Rome. Unfortunately–and this was a continuing bone of contention writing the screenplay–he also drove the Jews out of Jerusalem, thus setting into motion the problems that beset the Middle East to this day.

The film was to be directed by the great John Boorman who had done two of my favorite films, Point Blank and Deliverance. Boorman at that point had spent seven years trying to get Memoirs off the ground.

The film was to be directed by the great John Boorman who had done two of my favorite films, Point Blank and Deliverance. Boorman at that point had spent seven years trying to get Memoirs off the ground.

Lately, he had hooked up with a couple of Italian producers who fought with each other constantly. One of them wanted me in Rome, the other–Fellini’s pal with the apartment overlooking Via Veneto–didn’t.

I had run into this sort of conflict before. When there are a number of producers–and there are always lots of producers–the writer will have his allies and his enemies. The challenge is to figure out who is playing what part. In this case, it wasn’t difficult to identify my nemesis.

I was to spend the next four months in Rome working on the script. The production company put me up in a lovely apartment at 135 Via Sanzeno in a northern suburb that reminded me of Beverly Hills. During the week, I was provided with a car and a driver, Gianni, who, seeing that I ate an apple each morning, taught me how to say, “An apple a day keeps the doctor away,” in Italian.

Five days a week, Gianni would drive me to work through Rome’s rush hour traffic, me eating an apple, him yelling “Traffico!” The film company occupied pleasant offices with high ceilings at 197 Via Antonio Bertoloni. There I worked away until one o’clock. Promptly at that hour everything shut down, and we all went to lunch at one of the luncheon bars that had grown up around the city in the wake of the government’s decree that all employees be provided with vouchers for what amounted to a subsidized lunch. The lunch places were crowded, the food fresh and delicious.

On the weekends, the producer who was my ally announced, I was on my own. No car would be available. I imagined myself alone, not knowing anyone, trapped in an apartment seemingly in the middle of suburban nowhere for the next four months. I yelled and screamed. The producer acquiesced. I was allowed to use the car on weekends. Thus I learned that when it comes to negotiating with Italian movie producers, a little yelling and screaming is sometimes necessary.

Left to my own devices with a car, I promptly got lost. Outside the Old City where all the tourists are, English-speaking Romans are hard to come by. The street light and the street sign, if they exist, are extraordinarily well hidden.

A newcomer who doesn’t speak Italian, whose wife often accuses him of lacking any sense of direction, driving around a city he doesn’t know late at night, can find himself in big trouble–which is exactly where I found myself. I got seriously lost any number of times. Only by the divine providence of the Roman gods, not to mention blind luck, did I manage to find my way back to Via Sanzeno.

Even during daylight hours, I became lost with breath-taking ease. One Sunday afternoon after driving aimlessly around for several hours with no clue as to where I was, I stumbled across Via Veneto, a street I at least recognized. Since it was a tourist area, there was bound to be an English-speaking Italian.

I got out of my car and approached a parked taxi. The driver spoke English. “Look, I said, “I want to go to Via Sanzeno, but I want to follow you in my car.” The driver never even blinked. “Follow me,” he said, and with a good Roman taxi driver leading the way, I got safely home.

After that, the film company bought me a TomTom GPS device. It saved my life. With it attached to the dashboard, I never again got lost. That is not to say, however, I didn’t get into more trouble.

Armed with my new GPS, I merrily drove into the center of Rome, amazed that I could find a parking spot at the bottom of the Spanish Steps. There was good reason for my ability to find a parking spot–you’re not supposed to park there; I was not even permitted to drive my car into the center of town as it turned out. The tickets flowed.

Rome really does empty out in August. The Old City is flooded with tourists, but the area around Via Bertoloni became a ghost town. The shops and restaurants all closed. The streets were empty. I continued to come into the office every day and work on the script.

John Boorman would fly in from Ireland every other week to review our progress. Mostly he pronounced himself satisfied. The Italian producer who was my ally liked the script., too. Fellini’s pal, predictably, did not. Unfortunately, the producer who liked the script had a problem: he could not read English.

Ah, well.

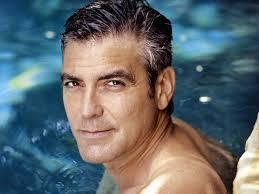

Toward the end of the summer the producer with the Via Veneto apartment attended the Venice Film Festival and met George Clooney. He immediately decided that Clooney would be perfect to play Hadrian. Never mind that Hadrian was gay and obsessed with the beautiful, underage Antinous, a love affair that practically destroyed him after the boy drowned. Boorman reacted with head-shaking disbelief when he heard the Clooney idea. So did I.

But who was listening to the director, let alone the lowly screenwriter? Producers, distributors, and financiers all hopped on a plane and flew to Lake Como where Clooney had a villa. The one person they did not take, curiously enough, the guy who might actually have been able to persuade the actor, was John Boorman.

Nonetheless, the Get George Gang returned convinced Clooney would do it. Boorman just shook his head some more.

Eventually, the word came back: George Clooney would not be wearing a toga. No surprise there.

The summer drifted into fall. Everyone came back to work. Our one o’clock lunches resumed. I successfully navigated around Rome. Boorman continued to fly in and out. Everyone said they liked the script. Everyone that is but the producer with the apartment overlooking Via Veneto.

The screenwriter and novelist Richard Price once said that as soon as they tell you they love the script, get your hat because you are about to be replaced. One day they said they loved the script. It was time to leave Rome.

Sure enough, shortly after I got home, another writer was hired to do a rewrite. The work on The Memoirs of Hadrian would continue. And continue.

.And continue…

There never was a Hadrian movie, and I long ago spent the money they paid me. What’s left is what counts: the memory of that summer lost in Rome.

August 9, 2013

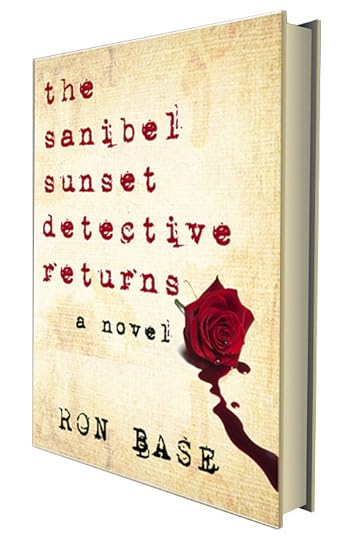

Download The Sanibel Sunset Detective Returns This Weekend–For FREE!

As part of the celebrations around the launch of The Sanibel Sunset Detective’s new website,Amazon is offering a free download of The Sanibel Sunset Detective Returns this weekend. From now through Sunday, you can discover the exciting world of Tree Callister, Sanibel Island, Florida’s most unlikely private detective at no charge.

As part of the celebrations around the launch of The Sanibel Sunset Detective’s new website,Amazon is offering a free download of The Sanibel Sunset Detective Returns this weekend. From now through Sunday, you can discover the exciting world of Tree Callister, Sanibel Island, Florida’s most unlikely private detective at no charge.

To get your free download, please click HERE.

And you can check out the new Sanibel Sunset Detective website by clicking HERE.

Want to try the other Sanibel Sunset Detective adventures? Right now The Sanibel Sunset Detective and Another Sanibel Sunset Detective can be downloaded for only $2.99.

To download your copy of The Sanibel Sunset Detective, click HERE.

To download a copy of Another Sanibel Sunset Detective, click HERE.

July 31, 2013

Forever, Clinton

We lost a beloved family member yesterday.

Clinton was the one with four legs and floppy ears.

We lost a beloved family member yesterday.

Clinton was the one with four legs and floppy ears.

My wife Kathy and I held him in our arms at 6:15 last evening and told him how much we loved him as he drifted into an endless sleep. Clinton was fourteen when he left, and today the house where he lived–generously, he allowed us to share it with him–is empty and haunted.

He was, as we told him all the time, the world’s best dog. He enriched our lives beyond the measuring–I doubt we would have a social life in Montreal or Milton were it not for Clinton introducing us around. At a time when Death seems particularly greedy for new victims, this is the one that will be the hardest to come back from. I’ve shed a lot of tears in the last few weeks. There is a flood today.

A couple of years ago, I wrote about Clinton when he turned twelve. The words I wrote then resonate now more than ever…

Everyone comments on his long floppy ears. His big soulful eyes give the impression he is not a happy camper, even though I believe he is happy. Certainly we bend over backwards to please him.

He is the star of our family, the celebrity who gets all the attention whenever he ventures into public view. I long ago stopped referring to Clinton as “our dog.” He is not “our dog;” we are his family. Except that Clinton gets better care and attention than the rest of us. That is the way it should be. After all, he is Clinton, and we’re not.

After all, he is Clinton, and we’re not.

I’ve been thinking of writing something about Clinton for some time, if only because it’s impossible to say much about my life without mentioning him.

He is a hound dog, but unusual in that he is a French hound, or Porcelaine, a breed employed for hunting in his native France. They are, I usually tell those who ask (and someone always asks), the French equivalent of the English fox hound that you see in those hunting prints people who should know better used to hang on their walls.

Clinton just turned twelve, so his hunting days are over–except when he sees a cat out the window. Then he is once again the chasseur but at a safe distance, employing nothing more threatening than his full-throated howl–impressive, the neighbors who hear him tell me.

My son Joel says Clinton is the most human dog he has ever met. He’s right. The longer we have him, the more human he becomes. Certainly, he is often the only member of the family who will listen to me.

We have had Clinton since he was a puppy, eight weeks old. When he first arrived home, I laid down the law. Two things were absolutely non-negoiatable: Clinton could not sleep on our bed, and Clinton could not go running with me in the morning. That was my time. I was not about to share it with a dog.

Clinton goes running with me every morning. And he slept with us every night until this year when getting up on the bed became too much for him. Charles Schultz was absolutely right. Happiness really is a warm puppy.

He has become more obstinate as he ages. If he does not want to walk in a certain direction, he stops dead in his tracks and refuses to budge. He then indicates the path he would prefer. Iron disciplinarian that I am, I go along with him.

We have gotten older together. He has been the constant in my professional life for practically as long as I can remember, the (mostly) quiet presence each day offering solace as I curse and swear and carry on at the indignities and disappointments of being a writer.

The most amazing thing about Clinton–as it is with most dogs–is that he only knows how to love you, and all he requires is to be loved back. That’s it. A simple unbreakable pact between us.

The thought that someday soon he may not be here, curled up on the sofa next to me, walking me over to the fairgrounds for our morning run, greeting me at the door with a shoe in his mouth–his constant gift for new arrivals–brings tears to my eyes.

So I do not think about that. Oh, I may be in London watching the National Theatre Production of War Horse, and I do not see the endangered horse on stage, I see Clinton, and that starts me blubbering. But mostly I’m able to keep such thoughts at bay.

He’s slower than he used to be, and I worry that his joints will give out, and those spindly hound dog legs won’t support him any longer. Like me, he is closer to the end than the beginning. But he endures.

And he loves. And he is so loved back. Here he comes now, moving out of the bed he has lately co-opted in the guest bedroom, a little stiff until he gets the kinks out of his joints. Time for our afternoon walk.

He will dawdle a bit, as is his wont these days. But that’s okay. I’ll wait for him. I know he would wait for me.

July 22, 2013

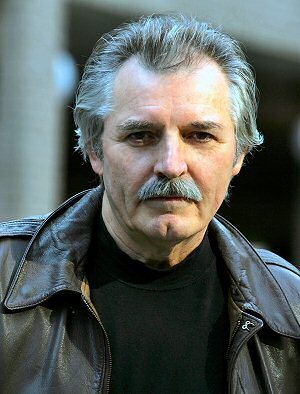

Not Fade Away: Brian Vallée Two Years Later

What scares me most about losing the people you love is how they tend to stay lost.

What scares me most about losing the people you love is how they tend to stay lost.

Perhaps it is the survival mechanism of the living, the concentration of daily life, the necessity to keep putting one foot in front of the other, but those who are not here any longer inevitably, it seems, begin to fade away.

The fight is to somehow keep the dead living. You fight with words. Words form the memories.

Two years ago today, my closest friend, Brian Vallée, died of cancer at St. Michael’s Hospital. I was holding his hand when he exited, yet now that painful moment seems somehow surreal, as if it never happened. But it did. Today. Two years ago. My oldest friend.

Gone.

But we don’t forget. We fight against forgetting. Hardly a day goes by when I don’t think “I’ve got to phone Brian about this.” Only to realize I can’t. Even now I can hardly believe he’s gone. Everyone who talks about him says the same thing. We keep him alive by not quite believing he’s dead.

When I first wrote about Brian, this blog was new, and it did not have nearly so many readers as it has now. So for those who have not met Brian before, you will hopefully get to know more about a unique individual who left us too early.

For those who knew him, a few moments of remembrance…

The digital readout on the phone said: “Vallée B.” In addition to everything else he’d accomplished, I told him, he had become a rap artist. He liked that idea.

The digital readout on the phone said: “Vallée B.” In addition to everything else he’d accomplished, I told him, he had become a rap artist. He liked that idea.

When he called, I knew it was time for my daily dose of the Vallée B News: another old newspaper pal gone; a new piece of information unearthed for the Edwin Alonzo Boyd book; the trouble editing the Conrad Black biography; the endless frustrations with a publisher over his latest book.

I always got the chapter and the verse. More than I sometimes wanted to know. But that was okay. He was Brian, after all, Vallée B. We talked nearly every day for over forty-two years. I don’t think we ever exchanged an angry word. Lots of jokes and arguments and jibes. But no anger.

The 70-year-old more formally known as Brian Vallée was a great newspaperman, an award-winning broadcaster, and a best-selling author. But to me he was simply and inevitably, Vallée B, that reassuring humor-filled voice on the phone, my closest and dearest friend.

He got me married twice (the second time as best man), helped me through a divorce, ran interference with various girlfriends when I was single, and when no one else would publish me, resurrected a publishing company he helped create, West-End Books, rolled up his sleeves and set about publishing my novel—an act of kindness and unwavering generosity that has quite literally changed my life.

It wasn’t just me, though. Brian was like that with everyone. If you needed help, Brian was there to provide it. He spent too much time trying to help everyone—dying pals, unemployed newsmen, frustrated writers, wannabe journalists. Brian seldom said no to anyone.

He was handsome and charismatic, larger than life. Everyone he met just naturally gravitated to him. He was one of those people who existed within this special aura that acted as a magnet drawing everyone he encountered.

I remember the moment I met him— lunchtime in 1969 at the Windsor Press Club. We were both reporters at The Windsor Star. I remember thinking he was somewhat shy and quiet. The next thing, I started hearing rumblings, stories from the late night front lines about this new guy Vallée. Not so quiet, as it turned out. Not so shy. A character.

He liked to play the piano late into the night. He did a little Johnny Cash and less Jerry Lee Lewis. He had a singular fault when it came to piano playing: he did not know a single tune. This, however, did not stop him. He played with ferocity and passion. So what if he didn’t quite know the whole song—or even half of it.

The amazing thing is, no one seemed to mind. Rapturous audiences would demand more. I used to wonder what they thought they were hearing. It wasn’t the music of course—there was no music—it was Brian. Everyone loved Brian.

But there was much more to him than his ability (as impressive as it was) to hold court around pianos. He also worked harder at his craft than just about anyone I ever knew. He took the business of journalism very seriously; the necessity to be accurate and true was paramount to him.

I don’t think he started out as a good writer, but he certainly finished up that way. The mellowing effect of the years, as well as his enduring relationship with his partner,Nancy Rahtz, provided him with a gravitas that opened the way to his finest work.

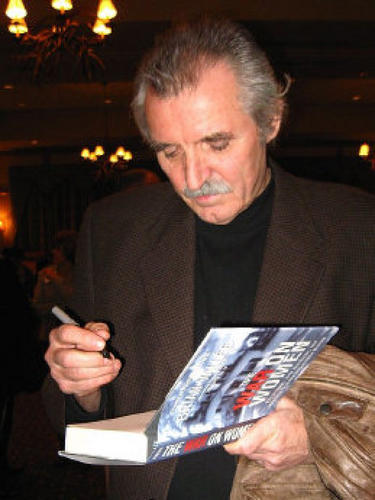

His last book, The War On Women, is also his best, a well-researched, eloquent cry for help for the victims of domestic violence.

In the past two years, he had become a passionate advocate for vulnerable women,and traveled the country speaking out for them. His fight for more awareness of domestic violence substantially raised the profile of that issue. He leaves a real legacy, a record of achievement few journalists can ever lay claim to.

There was so much more he wanted to do. Brian’s phone calls were filled with ambitious future plans both as an author and as a publisher. I marveled at what he wanted to do, wondered how he would ever get it all done.

But at the same time, those calls were filled with increasing complaints about back pain. He thought he had pulled something exercising. Instead of getting better, however, the pain grew worse.

His doctor sent him to physiotherapists. They provided no relief whatsoever. He could not work he was hurting so much. Now when he phoned his voice sounded weak. He seemed much older. Something was wrong, I said. This had to be more than a pulled muscle. Finally, blood tests were done. His doctor ordered him to get to a hospital.

He went into St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, May 14. He never left. Yesterday morning at 10:33 a.m., with wonderful Nancy at his side, Brian went away. I got there a moment before he left. I took his hand in mine, and he was gone.

So that is how forty-two years of friendship slips off; how the best friends leave. As he escaped away, I shouted how much I loved him, and how much he had meant to me—how I would miss him.

He just kept going. I hope he heard me.

Brian’s first book, Life With Billy, has become a non-fiction classic and a perennial bestseller. It is the heart-breaking true account of a woman’s battle against the monster that is her own husband, a modern-day horror story. It’s now available as an e-book on Amazon. Please check it out HERE.

July 19, 2013

Gina Mallet Remembered

The first time I heard of Gina Mallet, the Toronto theatre community was trying to get her fired.

A press conference had been called to demand that something be done about The Toronto Star’s new drama critic, a former Time magazine writer from New York who had recently arrived in town and was taking no prisoners. Amazed that anyone would be so upset with a newspaper critic that they would publicly call for her head, I went along to the press conference.

It wasn’t that Gina was incompetent or inaccurate, that is not what had raised the ire of this group, it was simply the fact that she was tough. Witnessing this spectacle, the like of which had not been seen before and hasn’t happened since, I thought to myself, This is my kind of critic.

(The public whining only ensured a major newspaper like The Star would never do anything but back Gina, which it did.)

In her heyday, Gina Mallet was a throwback to the kind of critic personified in the 1960s by Nathan Cohen at The Star and (to a lesser extent) Ron Evans at The Toronto Telegram, demanding, uncompromising writers, highly articulate, gleefully holding the feet of the arts community to the fire.

Gina was a brilliant drama critic–her perceptions of Shakespeare and what Stratford annually did to the Bard constituted some of the best theatre writing Toronto journalism has ever produced.

In life, Gina was as tough and uncompromising as she was in print. She did not suffer fools or editors, particularly, as they often did, when the fools and the editors came packaged together. Then Gina’s rages became a breath-taking performance art played out in The Star’s newsroom, a shock and awe campaign wondrous to behold–and not a little frightening, particularly if you happened to be the hapless editor on the receiving end.

Years after that press conference, I finally met Gina when I joined The Star to write first about television and then film. We became friends, joined in part by our mutual distrust of the editorial powers trying to run our lives. Those of us who worked in entertainment back then were an unruly but loving family, held together by the outside forces who daily conspired–as far as we were concerned–to cut our copy, reduce our editorial space, and generally make our lives as miserable as possible.

Small and heavyset, russet curls knit tightly to that patrician head, possessed of a mid-Atlantic drawl that would have been at home in a Noel Coward play, she was a fearsome adversary with enemies and adversaries galore. There was no one she wouldn’t take on from newspaper editors to restaurant owners to landlords.

Small and heavyset, russet curls knit tightly to that patrician head, possessed of a mid-Atlantic drawl that would have been at home in a Noel Coward play, she was a fearsome adversary with enemies and adversaries galore. There was no one she wouldn’t take on from newspaper editors to restaurant owners to landlords.

Whatever Gina was, whatever you thought of her, she was an original, and when she had an opinion on something–and she had an opinion on everything–God help you if you disagreed.

Once we auditioned together for a CBC radio show–critics sitting around discussing the popular culture of the day. Gina was so ruthlessly aggressive with her views that she sent one of the more milquetoast critics on the panel scrambling for the hills and made the CBC rethink any idea it had about allowing opinionated rabble such as ourselves onto the public airwaves.

Those of us who knew Gina also knew a softer, funnier, most generous friend. When my marriage fell apart, I soon found myself part of her regular Saturday night dinner parties, and there a calmer, sweeter Gina with a glass or two of good wine inside her, presided over delicious meals she prepared in her tiny kitchen. She had a lovely Cheshire cat smile, and when she was happy about something, she flashed that smile and nearly purred with delight.

She was a superb cook, even more knowledgeable and articulate about food than she was theatre–a knowledge she put to good use in later years as the restaurant critic for The Globe and Mail and The National Post.

She even wrote an award-winning book, a delightful combination of memoir and cri de coeur for the fate of good food titled Last Chance to Eat. In the book, I encountered a Gina I had not known before, the child of well-to-do British parents who grew up on a farm during the Second World War, and whose family later occupied a London apartment over Harrods department store.

There was an enigmatic quality about Gina. You knew her but didn’t really know her. There were parts of herself that she kept to herself. I saw a fair amount of her in the past few years, usually at lunch along with Jim Bawden, The Star’s former television critic. We would join Gina as she invaded various eateries in pursuit of her next restaurant column.

These were delightful lunches, the three of us yet again picking over the long-ago sins of The Star editors we’d had to suffer through, trading the newspaper gossip of the day, listening quietly to Gina’s delightfully barbed political views–slightly, shall we say, to the right of the center.

I knew she had previously battled cancer, and I knew she had fallen on hard times after leaving The Star and more recently when she lost her food column in The National Post. The lunches dwindled, I think mostly because she just couldn’t afford them any longer.

What I didn’t realize until it was too late, was that Gina’s cancer had returned, and this time it wasn’t going away. She died yesterday, and I sit here today writing this in tears, remembering someone who gave her heart and soul to journalism, who pursued the written word with total commitment and endless passion, and yet got so little back. She deserved so much better.

But then she gave so much to those of us fortunate enough to be her friend. As sad I am today, I can’t help but smile knowing she is off somewhere making life difficult for an editor.

Shock and awe, Gina. Shock and awe. Go to it, sweetheart…

.

Gina

The first time I heard of Gina Mallet, the Toronto theatre community was trying to get her fired.

The first time I heard of Gina Mallet, the Toronto theatre community was trying to get her fired.

A press conference had been called to demand that something be done about The Toronto Star’s new drama critic, a former Time magazine writer from New York who had recently arrived in town and was taking no prisoners. Amazed that anyone would be so upset with a newspaper critic that they would publicly call for her head, I went along to the press conference.

It wasn’t that Gina was incompetent or inaccurate, that is not what had raised the ire of this group, it was simply the fact that she was tough. Witnessing this spectacle, the like of which had not been seen before and hasn’t happened since, I thought to myself, This is my kind of critic.

(The public whining only ensured a major newspaper like The Star would never do anything but back Gina, which it did.)

In her heyday, Gina Mallet was a throwback to the kind of critic personified in the 1960s by Nathan Cohen at The Star and (to a lesser extent) Ron Evans at The Toronto Telegram, demanding, uncompromising writers, highly articulate, gleefully holding the feet of the arts community to the fire.

Gina was a brilliant drama critic–her perceptions of Shakespeare and what Stratford annually did to the Bard constituted some of the best theatre writing Toronto journalism has ever produced.

In life, Gina was as tough and uncompromising as she was in print. She did not suffer fools or editors, particularly, as they often did, when the fools and the editors came packaged together. Then Gina’s rages became a breath-taking performance art played out in The Star’s newsroom, a shock and awe campaign wondrous to behold–and not a little frightening, particularly if you happened to be the hapless editor on the receiving end.

Years after that press conference, I finally met Gina when I joined The Star to write first about television and then film. We became friends, joined in part by our mutual distrust of the editorial powers trying to run our lives. Those of us who worked in entertainment back then were an unruly but loving family, held together by the outside forces who daily conspired–as far as we were concerned–to cut our copy, reduce our editorial space, and generally make our lives as miserable as possible.

Small and heavyset, russet curls knit tightly to that patrician head, possessed of a mid-Atlantic drawl that would have been at home in a Noel Coward play, she was a fearsome adversary with enemies and adversaries galore. There was no one she wouldn’t take on from newspaper editors to restaurant owners to landlords.

Small and heavyset, russet curls knit tightly to that patrician head, possessed of a mid-Atlantic drawl that would have been at home in a Noel Coward play, she was a fearsome adversary with enemies and adversaries galore. There was no one she wouldn’t take on from newspaper editors to restaurant owners to landlords.

Whatever Gina was, whatever you thought of her, she was an original, and when she had an opinion on something–and she had an opinion on everything–God help you if you disagreed.

Once we auditioned together for a CBC radio show–critics sitting around discussing the popular culture of the day. Gina was so ruthlessly aggressive with her views that she sent one of the more milquetoast critics on the panel scrambling for the hills and made the CBC rethink any idea it had about allowing opinionated rabble such as ourselves onto the public airwaves.

Those of us who knew Gina also knew a softer, funnier, most generous friend. When my marriage fell apart, I soon found myself part of her regular Saturday night dinner parties, and there a calmer, sweeter Gina with a glass or two of good wine inside her, presided over delicious meals she prepared in her tiny kitchen. She had a lovely Cheshire cat smile, and when she was happy about something, she flashed that smile and nearly purred with delight.

She was a superb cook, even more knowledgeable and articulate about food than she was theatre–a knowledge she put to good use in later years as the restaurant critic for The Globe and Mail and The National Post.

She even wrote an award-winning book, a delightful combination of memoir and cri de coeur for the fate of good food titled Last Chance to Eat. In the book, I encountered a Gina I had not known before, the child of well-to-do British parents who grew up on a farm during the Second World War, and whose family later occupied a London apartment over Harrods department store.

There was an enigmatic quality about Gina. You knew her but didn’t really know her. There were parts of herself that she kept to herself. I saw a fair amount of her in the past few years, usually at lunch along with Jim Bawden, The Star’s former television critic. We would join Gina as she invaded various eateries in pursuit of her next restaurant column.

These were delightful lunches, the three of us yet again picking over the long-ago sins of The Star editors we’d had to suffer through, trading the newspaper gossip of the day, listening quietly to Gina’s delightfully barbed political views–slightly, shall we say, to the right of the center.

I knew she had previously battled cancer, and I knew she had fallen on hard times after leaving The Star and more recently when she lost her food column in The National Post. The lunches dwindled, I think mostly because she just couldn’t afford them any longer.

What I didn’t realize until it was too late, was that Gina’s cancer had returned, and this time it wasn’t going away. She died yesterday, and I sit here today writing this in tears, remembering someone who gave her heart and soul to journalism, who pursued the written word with total commitment and endless passion, and yet got so little back. She deserved so much better.

But then she gave so much to those of us fortunate enough to be her friend. As sad I am today, I can’t help but smile knowing she is off somewhere making life difficult for an editor.

Shock and awe, Gina. Shock and awe. Go to it, sweetheart…

.

July 7, 2013

Even Superheroes Love The Sanibel Sunset Detective

June 19, 2013

You Believed A Man Could Fly (Christopher Reeve Just Couldn’t Act)

The release of the new Superman movie, Man of Steel, put me in mind of my encounters with Christopher Reeve, the best of the Supermen and the star of what remains the most successful of the attempts to bring Superman to the screen.

The release of the new Superman movie, Man of Steel, put me in mind of my encounters with Christopher Reeve, the best of the Supermen and the star of what remains the most successful of the attempts to bring Superman to the screen.

The new movie has been released to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of pop culture’s original superhero, created by (writer) Jerry Siegel and (artist and Canadian) Joe Shuster. Man of Steel is such a loud, bombastic bore, so much a reproduction of all the other big, noisy CGI-heavy superhero movies flooding theaters at this time of the year, it threatens to drown out memories of the freshness and originality of the 1978 Superman: The Movie.

Up to that point, comic book heroes were relegated to the bargain basement of movie making–a low-budget Superman serial in 1948 and 1950, and then the iconic (but very cheaply done) black and white TV series starring George Reeves from 1952 to 1958.

Up to that point, comic book heroes were relegated to the bargain basement of movie making–a low-budget Superman serial in 1948 and 1950, and then the iconic (but very cheaply done) black and white TV series starring George Reeves from 1952 to 1958.

Directed by Richard Donner, Superman: The Movie delighted everyone by combining a comic book sensibility with a knowing humor, a lovingly executed romanticism, and what at the time were eye-popping, state-of-the-art special effects–you really believed, as the movie’s tag line promised, that a man could fly.

The best thing the movie had going for it was Chris Reeve. Born to wealth, he attended private schools, graduated from Cornell University, and had made only one other film before being chosen to play the role that had been turned down by just about every major star including Robert Redford, Burt Reynolds, and Nicolas Cage. Reeve brought the size (he was six feet, four inches tall), good looks (blazing blue eyes), and a certain sense of bemused innocence that was perfect for Superman.

The best thing the movie had going for it was Chris Reeve. Born to wealth, he attended private schools, graduated from Cornell University, and had made only one other film before being chosen to play the role that had been turned down by just about every major star including Robert Redford, Burt Reynolds, and Nicolas Cage. Reeve brought the size (he was six feet, four inches tall), good looks (blazing blue eyes), and a certain sense of bemused innocence that was perfect for Superman.

I didn’t meet him until the second movie in the series was released a couple of years later. Our first encounter took place at, of all places, Niagara Falls, where part of the story of Superman II was set.

In person, Reeve was much lankier than the pumped-up version of himself he employed for his Superman role, a quiet, intense and remote young man, with a rather patrician air about him that betrayed his background, friendly enough, but with, alas, not a whole lot to say for himself.

I say alas because although I’m not quite sure how I managed it, I ended up interviewing him more times than I care to remember, increasingly desperate as each interview approached to come up with the questions to which he invariably provided bland, uninteresting answers.

Unfortunately for Reeve, his blandness was not restricted to interviews–it also ended up on the screen. While his somewhat wooden demeanor worked well for him in the Superman films, it didn’t help him at all in other parts.

Without a blue suit and a red cape, he appeared uncomfortable onscreen and somehow detached from the words he was reciting–and he often sounded as though he was doing little more than reciting in films like Somewhere In Time (which somehow works despite Reeve and has become a minor classic), Deathtrap, and, most notoriously, a disaster titled Monsignor.

Without a blue suit and a red cape, he appeared uncomfortable onscreen and somehow detached from the words he was reciting–and he often sounded as though he was doing little more than reciting in films like Somewhere In Time (which somehow works despite Reeve and has become a minor classic), Deathtrap, and, most notoriously, a disaster titled Monsignor.

The Monsignor premiere, hosted by 20th Century Fox, the film’s distributor, was held in a mid-town Manhattan theater. A large press contingent was brought in to see the movie and interview the stars. Reeve was playing Father John Flaherty, a conniving Roman Catholic priest who falls in love with Canadian actress Geneviève Bujold.

Reeve came in and sat a few rows behind me. Presently, the lights went down, the audience quieted, and the movie started. Except the audience was not quiet for long. Almost from the moment Reeve appeared and opened his mouth, people started laughing. When Bujold showed up as solemn, humorless Clara, the young nun, the audience laughed even louder.

Soon everyone was howling throughout what was supposed to be an intense drama of a young priest blinded by ambition after World War Two. I longed to look back and see how Reeve was handling the audience’s reaction, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I had never attended anything quite like it before that night, and I’ve certainly not experienced anything like it since.

Among the reporters who witnessed this spectacle, it was widely predicted Reeve would never show up the next day for interviews. How could he, having been practically laughed out of the theater the night before?

But to his credit, Reeve did talk to reporters, toughing out the questions about the previous evening’s gales of unintentional laughter. You could not help but admire his nerve, even as you shook your head recalling the blank-faced ineptitude of his performance.

The last time I talked to him he was starring in Superman III, featuring comedian Richard Pryor, who wisely decided not to show up for interviews. By then the series had gone off the rails–Entertainment Weekly calls it the worst superhero movie ever made– and Reeve told me there would not be any more tights and capes for him.

But then, since none of his non-Superman roles brought either critical or box office success, he ended up doing a fourth movie, Superman IV: The Quest For Peace, by far the worst of the bunch, and a box office bomb–the movie Entertainment Weekly can’t possibly have seen if the magazine thinks Superman III is bad.

That was pretty much it for Reeve’s movie career. Ironically–and tragically–his real stardom would come in 1995 when he became paralyzed from the neck down after he was tossed from the horse he was riding at an equestrian event.

His subsequent fight for life, the courage he displayed, got him the kind of People magazine-cover-story attention he never had as an actor. He died in 2004 at the age of only fifty-two after suffering a heart attack. When he left, I tried to think about how great he was in that first Superman movie. I tried not to think about all those dull interviews.

The new Superman, British actor Henry Cavill, isn’t a patch on Chris Reeve, lacking the charm and the twinkle in his blue eyes that Reeve managed to bring to the role. Superman, along with just about everyone else in Man of Steel, barely cracks a smile amid the interminable confusion and carnage.

You believe a movie has been created inside a computer, but you never for a moment believe a man can fly.

Come home Christopher Reeve, all is forgiven–even Monsignor.

June 5, 2013

Fighting With Richard Burton; Dreaming of Cleopatra

The first time I met Richard Burton I got into a fight with him.

The first time I met Richard Burton I got into a fight with him.

I was wandering through the vast upper floor rooms inside a Rosedale mansion at a Saturday night party when I encountered him holding court, seated with his wife at the time, Susan Hunt. He had announced to the press that he wasn’t drinking, but on this late night he was drunk.

I joined the group, listening in. Burton babbled on about something that to my youthful ears made no sense. I said something to the contrary. Dead eyes filling with malevolence inspected me. He snarled. I snarled back. The room went dead quiet.

Abruptly, Susie Hunt announced, “Okay, that’s enough,” and rose to her feet, hauling Burton out of there. The next day the hostess called me, furious I had driven away her star guest. I was suitably shamed and embarrassed–not to mention angry with myself.

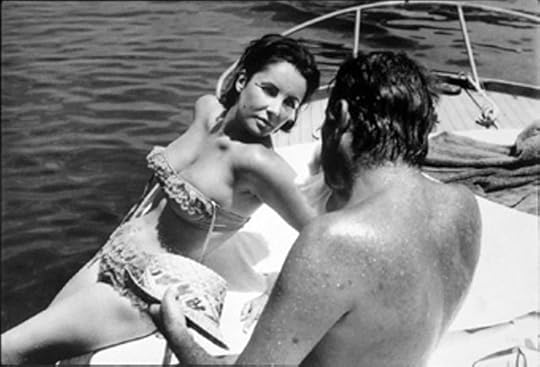

Burton had held a lifelong fascination, ever since he had come to scandalous prominence co-starring in Cleopatra with Elizabeth Taylor. The stories of their romance while shooting what became the most expensive movie in film history (over three hundred million in today’s dollars) had mesmerized me as a teenager. I could not get enough of Liz and Dick, as they came to be known in a million tabloid headlines.

Now here I was, finally meeting him, and I get into a senseless argument. What an idiot, I thought to myself.

All this came roaring back recently as I, much older and perhaps a little wiser, watched in a kind of dream state a newly-minted print of the four-hour version of Cleopatra. It has just been released on Blu-ray to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the movie’s June 12, 1963 premiere.

Viewing Cleopatra in this computer image-generated age where sets and backgrounds can be digitally produced and where ten extras can be transformed into an army of ten thousand, reminds one of the lengths to which Hollywood used to go in order to dazzle the eye–and Cleopatra’s lavishness certainly dazzles.

Viewing Cleopatra in this computer image-generated age where sets and backgrounds can be digitally produced and where ten extras can be transformed into an army of ten thousand, reminds one of the lengths to which Hollywood used to go in order to dazzle the eye–and Cleopatra’s lavishness certainly dazzles.

In stunningly sharp Blu-ray, the movie is a revelation: those really are vast armies, the barges are truly on the Nile, and Ancient Rome, if not built in a day, was certainly painstakingly reconstructed on a bigger, grander scale on the back lot at Cinecitta.

Stripped five decades later of all the hype and controversy surrounding its production, the movie, directed with such tenacity by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, reveals an intelligence and wit most epics of the time sorely lacked–intelligence and wit drawn unabashedly from Shaw and Shakespeare, but present nonetheless.

The first section, focusing on Rex Harrison as Caesar, remains the most impressive. Harrison is magnificent, and Elizabeth Taylor is surprisingly persuasive as the ambitious, seductive queen of the Nile. Dressed to kill, she breathes a sexuality you just don’t see in movies any longer. No wonder I was so intoxicated by her beauty as a kid.

The second part, featuring Burton’s Marc Antony, remains the most problematic. The length of the film becomes an impediment, and off-screen romance or no, Antony, as written by Mankiewicz, is a ruin and no match for his lover. It has been pointed out any number of times over the years that what was true on film was reflected in real life–Richard could never quite keep up with Elizabeth.

Still, they certainly led the world on a merry chase, as Furious Love, the best and most definitive book about the Burton-Taylor romance, makes clear. They were self-obsessed nomads in love, moving from five-star hotel to five-star hotel across the world, accompanied by servants, children, pets, and tons of luggage, making movies wherever they happened to land. They were the richest and most bizarre movie stars, restless spendthrifts seemingly incapable of settling down.

By the time I caught up with Elizabeth Taylor, Burton was years behind her–as was the fabled Taylor sexuality. The beauty remained on view, but you had to search it out in the center of a face grown round and plump.

She was married at the time to Senator John Warner, and professed to being blissfully happy, retired from movies, and playing the Washington housewife. None of it was true, of course. Taylor soon grew tired of the housewife, divorced the senator, and fled Washington.

When I stumbled upon him at that Rosedale party, Burton had married Susan Hunt, the former wife of the race car driver, James Hunt. She was said to keep a sharp eye on his drinking, although not very successfully the night I got into the fight with him.

After that mess, I never expected to hear from Burton. But a couple of weeks later, out of the blue, I received a phone call from the publicist on the movie he was shooting in Toronto, a romantic drama titled Circle of Two, directed by Jules Dassin. Burton played an aging painter in love with a much younger Tatum O’Neal.

After that mess, I never expected to hear from Burton. But a couple of weeks later, out of the blue, I received a phone call from the publicist on the movie he was shooting in Toronto, a romantic drama titled Circle of Two, directed by Jules Dassin. Burton played an aging painter in love with a much younger Tatum O’Neal.

Burton would see me the next afternoon. I have no idea if he remembered our Rosedale tangle. If he did, he gave no indication of it when we were introduced on the Circle of Two location. He slipped quietly onto the set, swathed in an air of melancholy. It was not hard to imagine why, ever since Cleopatra, he had been mostly cast in the role of the sadly ruined man, the archetype of Graham Greene’s burnt-out case.

Yet after we retreated to his trailer, he was affable and seemed in good spirits as he prepared coffee, his hands shaking a bit fighting to get the lid off a tin, recalling the crazy days when he was the co-star of the Liz and Dick travelling road show and could not go anywhere without attracting a crowd.

“I still don’t understand it,” he said. “It still happens every so often when from nowhere they suddenly appear. I long ago gave up arguing. I just smile and smile and sign the autograph.”

But not everyone knew him. He told a story about Elizabeth Taylor trying to find him while they were shooting The Comedians in West Africa. He said she phoned around to all the bars in town. When she got to the last one, she inquired of the bartender if Richard Burton was there. Who? The bartender said. Richard Burton, Taylor answered. He’s one of the most famous actors in the world. There was a pause before the bartender said, “noir ou blanc” –black or white?

Given the millions he made and the intensity of the public obsession surrounding him and Taylor, he nonetheless still managed to come across as something of a Welsh Everyman–albeit one with a magnificent, classically trained voice–bemused at finding himself the object of so much attention.

He exhibited–or appeared to exhibit–an unexpectedly carefree attitude toward fame and fortune, flying in the face of the more popularly held view that, along with the booze, these were the things that destroyed him. When I suggested he should write his autobiography, he shrugged off the idea. “I think I’ll leave that until I’m about seventy.” He paused. “If I make seventy, of course.”

We both chuckled, but in the end he didn’t even get close, dying of a heart attack at his home in Switzerland a few years later at the age of only fifty-eight. Taylor died two years ago, age seventy-nine.

After all this time we continue to be fascinated by them. Burton’s diaries were published last year (when Burton would have been eighty-seven, thus proving accurate his assertion he would wait until at least seventy before producing a memoir). An awful TV movie (with Lindsay Lohan, of all people, as Taylor) was broadcast recently. That hasn’t stopped talk of as many as five feature films based on the couple, including an adaptation of Furious Love directed by Martin Scorsese.

And, of course, there is Cleopatra, restored to glowing life at fifty.

“Everybody was insane,” Burton recalled of the time making the movie. “The whole world was bonkers.”

He laughed and shook his head and I laughed too, having a great time that afternoon with Richard Burton.

I agreed with everything he said. Probably why we didn’t get into a fight.