Ron Base's Blog, page 14

April 2, 2014

Down and Out in Beverly Hills: Jogging With Eartha Kitt, Lunch With Zsa Zsa Gabor, Escaping Fire With A (Half) Naked Blonde…

Memories of my years spent down and out in Beverly Hills flooded back the other day when I read that the town is celebrating its hundredth anniversary.

Memories of my years spent down and out in Beverly Hills flooded back the other day when I read that the town is celebrating its hundredth anniversary.

The Westside Los Angeles enclave, formerly a bean field transformed in the 1920s into a kind of sun-kissed Olympus for cinema gods and goddesses, remains the best known small town in America. The words Beverly Hills still resonate with all the clichés of Hollywood opulence. Even though I was probably the town’s poorest resident, people always look impressed when I tell them I once lived there.

Ostensibly, I moved to Los Angeles to write a book about movie stardom (it was eventually published in the U.S. titled, If The Other Guy Isn’t Jack Nicholson, I’ve Got the Part). However, there were other, more complicated reasons having to do with divorce, leaving a job, reinventing oneself. I was, as it turned out, in the world capital of self reinvention. Everyone there was from somewhere else. Everyone wanted to be something other than what they were.

Ostensibly, I moved to Los Angeles to write a book about movie stardom (it was eventually published in the U.S. titled, If The Other Guy Isn’t Jack Nicholson, I’ve Got the Part). However, there were other, more complicated reasons having to do with divorce, leaving a job, reinventing oneself. I was, as it turned out, in the world capital of self reinvention. Everyone there was from somewhere else. Everyone wanted to be something other than what they were.

I was right at home.

From the outset, I decided that if I was going to live anywhere in L.A., it was going to be Beverly Hills. As a kid from small town Canada who had grown up fascinated by the lore of Hollywood, I couldn’t imagine residing anywhere else.

Together with my longtime pal and soon-to-be roommate, Alan Markfield, we found an apartment at 320 North Palm Drive. At that time, the California economy was in such bad shape, rental units were going begging– they even gave us a month’s free rent in order to induce us to move in.

One of the many great things about having Alan as a roommate–other than the fact he was a pretty fair cook–thanks to his job as a movie stills photographer, he was seldom in town. I had this big, airy apartment overlooking North Palm Drive pretty much to myself.

One of the residents at three-twenty had written a screenplay about a talking baby. Another arranged flights for American businessmen to fly to Moscow to meet eligible Russian women looking for husbands. A petite young woman with a gravelly voice had once been a child actor on a popular kids’ TV show.

The white-washed four-story apartment building in which we all resided surrounded an open courtyard and featured a rooftop swimming pool right out of the 1940s. I would swim in the pool in the afternoons, and it didn’t take much to imagine Esther Williams doing laps alongside me.

North Palm Drive was the loveliest street I ever lived on. Each spring about this time, the Jacaranda trees lining either side of the street would break into bloom and form a violet-colored canopy.

At dusk, the crimson light that is so special to Los Angeles–the Chinatown light, I used to call it–would filter through the flowering Jacaranda and Beverly Hills would be turned into a beautifully lit, enchanted land where surely all your dreams could come true. Never mind that by the next morning they wouldn’t. For that one brief nighttime moment, you could believe anything, and life didn’t seem so bad at all.

Every morning, I jogged through the strip of parkland running along Santa Monica Boulevard where once the denizens of Beverly Hills rode their horses. You would encounter the most unexpected people on these morning runs: the actress Linda Hunt, also out jogging; Eartha Kitt, dressed head-foot in black strolling along the park’s pathway; the actor Gene Barry (the star of TV’s Bat Masterson and Burke’s Law) also out for a walk, nodding hello.

I never once drove along Sunset Boulevard in my rattletrap Mustang without thinking excitedly, “Gee, here I am, driving along Sunset Boulevard!”–evidence you can take the kid out of small-town Canada, but you can never quite take small-town Canada out of the kid.

I unfailingly got a charge out of seeing a movie (however bad) at the legendary Grauman’s Chinese Theatre (now called the TCL Chinese Theatre) that has dominated Hollywood Boulevard since 1927 and in whose forecourt you could stop to view the foot and handprints of Hollywood’s greatest stars–including Trigger’s hoof prints.

I unfailingly got a charge out of seeing a movie (however bad) at the legendary Grauman’s Chinese Theatre (now called the TCL Chinese Theatre) that has dominated Hollywood Boulevard since 1927 and in whose forecourt you could stop to view the foot and handprints of Hollywood’s greatest stars–including Trigger’s hoof prints.

The Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel was no longer quite the place to see and be seen, but it was so full of history it didn’t matter. Middle-aged screenwriters led by Carl Gottlieb, the guy who wrote the script for Jaws, gathered regularly at Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood to grumble about their lot in movie life.

Friday nights I would go up the street to meet my old Windsor Star colleague Ray Bennett at Dan Tana’s restaurant where he and his journalism pals from the L.A. Times and the Hollywood Reporter held court at the bar, rubbing shoulders with regulars such as actors James Woods and Dabney Coleman.

At lunch you could spot the director Billy Wilder engrossed in conversation–and marvel at being able to sit there staring at the legend who created Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot. Zsa Zsa Gabor would be at the next table. Not far away, Arnold Schwarzenegger lit a cigar in the days before he became The Governator of California. Milton Berle entered wearing a fedora and, of all things, an overcoat.

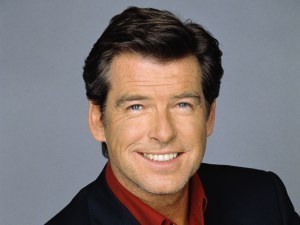

It seemed to me every time I ate out in the neighborhood, George Hamilton managed to show up. And here was Pierce Brosnan wandering around Book Soup, the best bookstore in Los Angeles–and there he was again entering the bar at the Four Seasons Hotel on Doheny Drive, just around the corner from my apartment.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the Northridge earthquake marked the beginning of the end of me and Beverly Hills. The worse earthquake in the modern history of Los Angeles struck at 4:31 A.M., shaking me out of a sound sleep.

With the whole building trembling violently, I hopped out of bed in my darkened bedroom. Not knowing what else to do, I stood in the doorway, vaguely recalling that a reinforced area would provide some protection.

It didn’t–and it is exactly the wrong thing to do, as I discovered when the door frame shook as badly as the rest of the building. No sooner was I thinking that this was a mistake, and wondering what to do next, than the shaking stopped. I couldn’t believe it. I had survived an earthquake in Beverly Hills.

I hurried onto the street where the rest of the neighborhood was already gathering. The power had gone out, but someone had a transistor radio tuned to coverage of the earthquake. One broadcaster noted, “It was like being shaken around in a shoe box.” Exactly what it was like.

Despite the widespread damage–including a freeway collapse just south of where I lived–I had escaped unscathed. By the time we were allowed back into the building, it was a beautiful Los Angeles morning. With nothing else to do, I went up to the rooftop and lay beside the swimming pool, reading a book.

Suddenly, the door to the penthouse apartment on the far side of the pool opened and a lovely blond-haired woman burst into view dressed in nothing but a thin bathrobe, and–I kid you not–high-heeled slip-ons. As she raced toward me, she started yelling something I couldn’t understand.

“What is it?” I said.

“Fire,” she cried. “There’s a fire!”

I couldn’t believe it. What fire? Frantically, she pointed behind me. I turned to see black smoke billowing up from the courtyard. Someone had left a candle burning in their apartment and the flame had ignited sheets of plastic.The apartment building was on fire.

The half-naked blonde and I made our escape down a flight of stairs.

Again, my luck held. Half the apartment building was destroyed–but not my half. I didn’t even suffer any smoke damage. Still, as it was for so many that morning, the earthquake acted as something of a wakeup call.

What was I doing with my life? I asked myself that question a lot over the following days. I was thousands of miles from home and family, down and out in a strange place where one moment the Jacaranda trees were blossoming and the next moment, the whole world was shaking.

Not long afterward, I met my future wife, Kathy. She made it very easy to decide to leave. Beverly Hills floated into Jacaranda-scented memory.

These days, the closest I get to Los Angeles is via the Showtime television series Californication. It’s a raw comedy about the life and loves of an L.A. writer named Hank Moody (played with a certain insouciant charm by David Duchovny).

Hank is a troubled soul but irresistible to endless numbers of beautiful young women with perfect breasts who can’t wait to get him into bed.I tell my wife that’s exactly what my life was like when I lived in Beverly Hills.

She rolls her eyes.

March 17, 2014

Tales From the Tour: Old Girl Friends, Movie Moguls, Sad Stories, and a Blind Raccoon

If I’ve learned anything the past couple of months it is this: Do not do a book signing with a blind raccoon.

If I’ve learned anything the past couple of months it is this: Do not do a book signing with a blind raccoon.

Trouper is the raccoon in question. Kyle Miller has written a children’s book devoted to Trouper’s adventures. She brings him along when she does a book signing. Guess who gets all the attention? Suffice to say it is not authors, ahem, of a certain age, flogging mystery novels.

Raccoons aside (although blind raccoons are difficult to put aside), you encounter the most fascinating people in the course of promoting The Sanibel Sunset Detective novels in South Florida, and you come away with the most amazing stories–cops and movie moguls and widowers, even a bittersweet reminder of a long ago teenage romance.

Raccoons aside (although blind raccoons are difficult to put aside), you encounter the most fascinating people in the course of promoting The Sanibel Sunset Detective novels in South Florida, and you come away with the most amazing stories–cops and movie moguls and widowers, even a bittersweet reminder of a long ago teenage romance.

A Republican state senator, Judy Lee, who has represented a North Dakota district since 1995, buys a book, as do the charming parents of Emma McLaughlin, one of the authors of the mega-selling The Nanny Diaries.

A speechwriter for, among others in the President Obama Administration, U.S. Defense Secretary, Chuck Hagel, drops by. You meet former staff sergeant Charlie Willis who saw action in the First Gulf War, and ended up in communications at the Bill Clinton White House. What did he think of Bill and Hillary? Charlie grimaces. “Not much,” he says.

Then there are the husband-and-wife Chicago police officers, Marti and Ed. When they met, it was as patrol car partners. They were called to an incident involving an armed man. When they appeared, the gunman opened fire. Ed stepped in front of Marti and took the bullet intended for her. Badly wounded, Ed nonetheless had the wherewithal to shoot and kill the gunman.

Marti saved his life by getting him quickly to hospital and then stayed with him until he recuperated. While she was sitting there hour after hour caring for the man who risked his life to save her, she began to think, This might be the kind of guy you could marry.

After he recovered, they did just that.

You meet so many fellow authors, to the point where you begin to suspect there are more authors than readers. Technology really and truly has changed the landscape for writers. The most unexpected people now publish their own books.

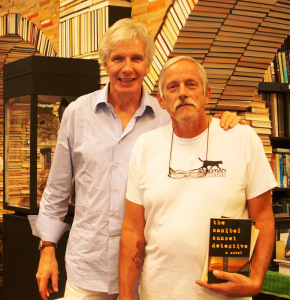

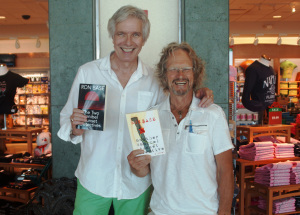

At the Big Arts Center on Sanibel Island, Hollywood mogul David V. Picker has a book to flog, a memoir of his years running United Artists and then Paramount and Columbia Pictures, rather awkwardly titled Musts, Maybes, and Nevers.

At the Big Arts Center on Sanibel Island, Hollywood mogul David V. Picker has a book to flog, a memoir of his years running United Artists and then Paramount and Columbia Pictures, rather awkwardly titled Musts, Maybes, and Nevers.

Picker self-published his book through Amazon’s CreateSpace. It’s a very good book from the man who ran United Artists at a time when it was the most innovative studio in Hollywood. Picker oversaw the acquisition of the James Bond franchise, and green lit such classics as Tom Jones, A Hard Day’s Night, Midnight Cowboy, and Last Tango In Paris.

Even as he delighted in his hits, Picker made certain his audience knew about his misses as well, particularly the George Stevens disaster, The Greatest Story Ever Told, one of the great financial flops of the era. Picker said he knew he was in trouble when John Wayne, portraying a Roman centurion, appeared on the screen.

The Duke looked down at Max von Sydow, who was playing Jesus Christ, and intoned in his trademark American drawl: “Surely, this man is the son of God!”

Doing book signings, you never quite know who is going to walk into your life or what ancient memories will be stirred. In high school in the Eastern Ontario town where I grew up, I dated a teenage beauty named Gabrielle. She soon dumped me for a guy with a sports car. I only had a Volkswagen Beetle with no fuel gauge. I was crushed.

Years later, in Toronto, single at the time and now driving a car with a fuel gauge, I encountered Gabrielle again. Destiny, I thought. We were meant to be, after all. I asked her out. She readily agreed.

At dinner, she began to cry. Was it me? Usually it took more than one date to start people crying. No, she said, she had just broken up with her boyfriend, and was still getting over it. Okay, I thought, we will get past this. After all, this is destiny; we were meant to be.

Another dinner. Gabrielle cried more. I began to think this wasn’t so much destiny as a woman in love with another guy. I departed the scene. Gabrielle returned to her boyfriend.

Now I am standing at the Fort Myers airport, silently lamenting my recent ill fortune at having become, against my will, a senior citizen, when I am approached by a small, sinewy man. He recognizes my name, but from where exactly? Robert became successful selling cars in Toronto, but before that he worked for a radio station in Brockville, Ontario. Well, I was from Brockville, I said.

Maybe that was it, he said. Maybe the girl he dated in Brockville had mentioned my name.

Oh, yeah? I said. What was his girlfriend’s name? Gabrielle, he said.

This was the guy! Robert was the boyfriend who had caused the dinner tears, the guy who had defeated my sense of destiny. As it turned out, he and Gabrielle were not destined to be either, but he still stays in touch with her. She is in her sixties now–hard to imagine–an interior designer, apparently none the worse for surviving all these years without either of us.

Two ex-boyfriends thrown together on the concourse at the Fort Myers airport can only shake their heads and laugh at the improbability of this encounter. I do what any author would do under such circumstances–I sell him a book.

And then there are the sad stories.

People tell you about the heartbreak in their lives. At the airport again, I talk to a woman on her way to bury her son-in-law who has died unexpectedly of cancer. A sad-looking white-haired man named Jeffrey wanders by, looking a little lost. We begin to talk. He has been on Sanibel Island trying to put himself back together again after the death of his wife three months ago.

They were in New York celebrating their anniversary. She was tired, but there was no other indication anything was wrong. Then she collapsed. Rushed to hospital she died sixty hours later. A rare auto immune disease. You love someone for so many years and then she is gone, Jeffrey said. What do you do?

What do you do? The author is left speechless. And in tears.

All of a sudden a book signing with Trouper the blind raccoon doesn’t seem so bad.

January 14, 2014

The Detroit Auto Show, A Woman Name Michele, A Failed Romance

The Detroit Auto Show got underway yesterday, and in the way I have lately of linking these things, the show always makes me think of a woman named Michele and the romantic, embarrassing mess of an encounter I had with her so many years ago–an encounter that defined my naïve adolescence and which to this day, at this time of the year, makes me shake my head.

The Detroit Auto Show got underway yesterday, and in the way I have lately of linking these things, the show always makes me think of a woman named Michele and the romantic, embarrassing mess of an encounter I had with her so many years ago–an encounter that defined my naïve adolescence and which to this day, at this time of the year, makes me shake my head.

She said she spotted me as I wandered through the auto show. She was one of the models employed to make the cars look better, I suppose. But I didn’t meet her until a few days later when I attended a party in Detroit for author Harold Robbins. No one much talks about Robbins now, but back then he was the world’s bestselling author of such sex-saturated tomes as The Carpetbaggers and The Adventurers.

She said she spotted me as I wandered through the auto show. She was one of the models employed to make the cars look better, I suppose. But I didn’t meet her until a few days later when I attended a party in Detroit for author Harold Robbins. No one much talks about Robbins now, but back then he was the world’s bestselling author of such sex-saturated tomes as The Carpetbaggers and The Adventurers.

By the time I met him, Robbins had started to run out of gas on the bestseller list, so he was hitting the road promoting his latest novel. Michele—although she called herself Mickie then—was one of the models hired for the occasion to help promote Robbins as the real life incarnation of the irresistible sexual stud he wrote about. The deception did not work. Robbins turned out to be a charmless blowhard who grabbed at his crotch a lot and made lewd comments. The women stampeded away.

Mickie was sleek and doe-eyed, African-American, and, to my astonishment, interested in me–thanks apparently to that first sighting at the auto show. Even Robbins sensed there was something happening here, and stayed away.

She was from Chicago, she said, and worked part-time as a model and also as a ticket agent for American Airlines. Ah, youth. I was smitten. After that first night with her, I called her regularly for several weeks. We had great phone conversations, that deep, purring voice late at night on the line from Chicago. Finally, she invited me to visit for a weekend. I couldn’t wait to get on a plane.

Mickie picked me up at O’Hare Airport and checked me into a hotel on Chicago’s South Side. Her apartment was nearby. She was warm and welcoming. I was nervous and trying to act a darn sight more mature and worldly than I was, this being the first time I had been in Chicago or been on a weekend date.

Saturday afternoon we met some of her friends. They invited us to a party that was happening that night. Mickie looked nervous and immediately demurred. Man of the world that I was, everyone’s pal, I insisted we attend. Her friends were delighted. Mickie looked more nervous.

The party was held in a well-to-do, snow-covered Chicago suburb full of grand two-story homes. As soon as I walked in the door I understood why Mickie might have been trepidatious. I was the only white guy there.

Everyone was friendly enough, but you could not help but feel a certain tension. This was 1970. Martin Luther King had been assassinated barely two years before. There had been race riots across the country. America was a much different place back then—a fact I should have been a lot more aware of than I was.

Still, everyone was friendly, and the evening seemed to be unfolding pleasantly. Then a well-dressed, middle-aged man sauntered over and said something about Mickie. I didn’t think I had heard him properly. Must be nice, me being a white man out with a black woman. Something like that. Then he got nastier, always in a friendly tone, but increasingly unpleasant. I tried to move away. He followed me. Mickie tensed, but she said nothing. In fact, no one said anything. No one tried to stop the guy. It was just me and him.

To say I was unprepared for this verbal assault is to severely understate the case. I was aware that I had been transported out into the suburbs with no idea where I was, and with no car. Mickie and I were trapped in a house full of people I didn’t know, with no means of escape.

Finally, the people who brought us decided to leave. Mickie no longer seemed present. Her face had become a lovely mask, showing nothing. I was numb. No one spoke on the way back into town.

They dropped me off at my hotel and then drove Mickie home. I spent a sleepless night playing out scenarios that had me responding to the confrontation a whole lot better than I actually had.

The next morning, I called Mickie’s apartment. No answer. Then came a knock on the door. I opened it to find her standing there looking perplexed. She wanted to talk. She came in and sat down and said she was distressed about what happened the previous night. She was particularly upset by the way I handled it. “Why didn’t you do something?” she demanded. I was stunned. What was I supposed to have done?

“You should have done something,” she insisted.

But I hadn’t, and it was obvious she thought much less of me for it. The rest of the day passed in blur. In retrospect, I can’t imagine why we did, but for some reason we drove to her mother’s place. She had been active in Chicago’s civil rights movement, a lovely woman in an apron, probably wondering what the hell this complete stranger was doing in her living room.

Later, we went back to the hotel. I collected my bag, she kissed me perfunctorily, and I got in a cab to the airport—devastated.

I never heard from Mickie Clark again.

Two years later, Michele, as she now called herself, had graduated from the Columbia School of Journalism and become a reporter for WBBM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Chicago. Shortly after that, she was hired as a correspondent for CBS News. Beautiful, assured, articulate, with that deep, resonant voice I remembered from our phone conversations, she was a rising star on Walter Cronkite’s newscast.

She was one of the reporters covering the Watergate scandal that would destroy Richard Nixon’s presidency. In December 1972, she boarded a United Airlines flight from Washington to Chicago accompanying Dorothy Hunt, the wife of E. Howard Hunt, one of the Watergate burglars.

On its descent into Chicago’s Midway Airport, the plane crashed, killing forty-three of the sixty-one passengers on board. Hunt’s wife was among those who died.

So was Mickie Clark. She was twenty-nine years old.

Officially, pilot error caused the plane to go down. But over the years there has been speculation that the CIA wanted to silence Mickie and Dorothy Hunt and thus somehow orchestrated the crash.

Of all the Watergate figures the Nixon Administration might have conspired to kill, they would seem to have been marginal players at best. But who knows?

Mickie certainly is not forgotten around Chicago. They have even named a school after her–the Michele Clark High School.

And every year about this time, I do think of my brief, fumbling encounter with her. I think of what a short a short distance I have come, what a long distance she might have traveled. To her, I was probably a mistake one weekend in Chicago. For me, it remains the romance brought down by youthful shortcomings.

Age hasn’t given me much insight as to what I would do differently. Maybe today I would be smart enough to read Mickie’s signals and not go to the party in the first place. Would that have made any difference?

I still wonder.

January 2, 2014

Officially Old In The Real World; Forever Young In Paris

I didn’t used to be officially old, but now I am. If you are going to get old anywhere, it is best to do it in Paris, because Paris is ageless, and in Paris you are forever young.

I didn’t used to be officially old, but now I am. If you are going to get old anywhere, it is best to do it in Paris, because Paris is ageless, and in Paris you are forever young.

My wife Kathy and I have come here to ease my trauma at officially becoming what we call a senior. I know I am a senior because the Canadian government will now send me money. They call it–gulp!–the old age pension. Kathy so far appears to forgive me for being old, but then again, we are in Paris where just about everything is forgivable, even age.

We are staying in a one bedroom apartment on the colorfully named Rue des Deux-Ponts on the Ile Saint-Louis. The windows are of stained glass, the ceilings high and beamed, the lampshades a mustard-color, casting the apartment in an amber light suggesting the ghosts of the belle époque might be lurking in the shadows.

I have been coming to Paris in search variously (according to my age and mood) inspiration, enlightenment, good food, and a good time for over thirty years. I lived here for a time in order to write a not-very-good French movie titled Jesuit Joe for the blue-eyed son of an Arab billionaire (you can’t make this stuff up).

Kathy lived in Paris for two years, loves the city even more than I do, and speaks fluent French. Wandering around with her is always a treat since she sees things I never see, remembers streets and restaurants I never remember, and generally corrects my faulty French.

It is rainy and misty in Paris at this time of the year so we escape to the Paris Opera or the Palais Garnier as it is more formally known, Charles Garnier’s masterwork whose gilded opulence leaves a first-time visitor slack-jawed, and nearly drowns out the thinner pleasures of a ballet called Le Parc .

It is rainy and misty in Paris at this time of the year so we escape to the Paris Opera or the Palais Garnier as it is more formally known, Charles Garnier’s masterwork whose gilded opulence leaves a first-time visitor slack-jawed, and nearly drowns out the thinner pleasures of a ballet called Le Parc .

Later, we crowd inside Café de Flore, an old Hemingway haunt that’s been situated on a corner of Boulevard Saint-Germain since 1885. This Saturday afternoon, the waiters can’t move, you can’t move, the air is warm, the windows steaming.

Outside, cobblestone streets are slick and wet the way they should be when you are walking the boulevards gloomily contemplating a life lived–what? Fully? Isn’t it too early for this kind of review?

But then you are old, aren’t you, with less ahead and much more behind. Easier to look back these days then it is to see forward. The future, even in Paris, is more opaque than the windows at the Café de Flore on a rain-whipped Saturday.

Everything is fine now, you tell yourself, but there are dark tunnels ahead, and the reality is that no matter how hard you try to defeat it, old age has arrived and all you are going to do from here on in is become older and less healthy.

At a time like this I can’t help but think of the actor Henry Fonda. I interviewed him when he was sixty-five, and he looked terrific: still movie star lean and lithe and handsome. This was a guy who didn’t smoke, drank a single Scotch after a stage performance, and arrived at the Mayo Clinic every year for a week-long checkup.

Yet when I interviewed him again five years later, Fonda had been transformed into an old man, gray and wan and suffering various heath problems. A few years after that second interview, he was gone at the age of 77.

And he took care of himself. Where does that leave me? I’m trying not to think about it.

Thankfully, at least for now, Paris doesn’t allow much time for thoughts of mortality. We are in town with my pal Alan Markfield and his delightful wife, Christine Lalande. Alan and I met in Israel thirty-five years ago, young guys on the loose in the Holy Land, Markfield the ambitious photographer, Base the freelance magazine writer waiting around Eilat, hoping Tony Curtis might talk to him (Tony finally arrived astride, no kidding, a white stallion. You really can’t make this stuff up).

Since Israel, Alan and I have shared adventures around the world: we snorkeled in the Red Sea; ate the dog meat in China (okay, we tried the dog meat in China); stood in a snow drift in Barkerville, British Columbia; shot two movies together in Toronto.

He has dragged me out of more than one bar, and in the dead of night when I was single, he often served as the calming, reasoning voice on the phone as one relationship or another skidded into disaster. We even lived together for a couple of years in Beverly Hills, before Christine came along and took him away from me.

I’ve watched Alan develop from a struggling freelancer into one of the most successful stills photographers in the movie business. He has shot the still pictures for everything from Elf to Bond movies, to Escape Plan and the latest X-Men movie.

We’ve seen each other through a lifetime of marriages, divorces, and deaths. So here we are in Paris, the Boys together again, their poor wives forced to listen to oft-told stories dragged from the mists of time and retold, occasionally with something approaching accuracy..

On New Year’s Eve, we gather at L’Arpège, the Michelin three-star restaurant on Rue de Varenne, recommended to Christine by–not to drop names here–the actress Kathy Bates with whom Christine has worked on the TV series, American Horror Story.

The chef, Alain Passard, is regarded among the top five French chefs working today. He concentrates on vegetables grown in his own biodynamic vegetable gardens, and he has banned red meat, perhaps knowing that an aging Canadian who no longer reacts well to it, was on his way to the restaurant.

Passard emerges from his kitchen to warmly greet the evening’s guests, and then hurries back to oversee a New Year’s menu that includes Gratin d’oignon doux à la truffle noir (sliced onions with shaved black truffle), Velouté et crème souflée au Speck (a vegetable soup), Grand Rôtisserie d’heritage (a capon) and Pêche côttièr lotte (Monkfish).

The meal is not a meal but an epic production running over four hours, complete with a warm-hearted, witty cast of servers, midnight kisses all around, Chef Passard reappearing at the stroke of twelve to wish all his guests a “bonne année.”

Never mind that the cost of the evening is enough to make even a now officially old guy who sometimes (erroneously) believes he has seen it all, gasp, we float from L’Arpège after one o’clock having experienced one of the great meals of a lifetime, into a waiting taxi that transports us through rain-slicked Paris streets, still thick with celebrants unwilling to give up.

I hold tight to the woman I love so much, lost in ageless Paris, full of great food and good cheer, feeling, perhaps for the last time, forever young.

December 31, 2013

HAPPY NEW YEAR EVERYONE!

Thanks to everyone who has followed my adventures on this blog over the past year.Your support and enthusiasm has made the usually humorous, sometimes painful business of writing these pieces a delight. And many thanks to all the Sanibel Sunset Detective readers who have embraced Tree Callister and the gang on Sanibel Island. I could not have done it without you.

Onward and upward to a great 2014!

December 17, 2013

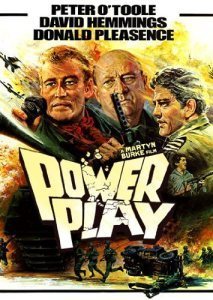

Remembering (Again) How I Nearly Killed Peter O’Toole

Since Peter O’Toole left the stage this past weekend at the age of eighty-one, there has been a huge outpouring of sadness and remembrance. It has been pointed out in his many obituaries that O’Toole encountered a few down periods during a rowdy and often tumultuous lifetime. My encounter with him took place during one of those down periods. He fooled me. He fooled us all. He was, after all, Peter O’Toole. Here is what I wrote about him in 2012 shortly after he announced his retirement from acting…

I thought I had killed off Peter O’Toole in 1978, so naturally it came as a surprise to read that he was retiring from acting a couple of weeks short of his eightieth birthday.

O’Toole was in Toronto making a thriller about a group of army officers plotting a coup d’etat in a fictional country. The movie, titled Power Play, was shooting in and around a local mansion. I arrived to spend some time with him on the set.

He was by this time legend, the star of Lawrence of Arabia, the carousing Irish lad who in company with his friend Richard Burton had heard the chimes at midnight so often that he had been forced for health reasons to stop drinking entirely.

In the days I hung around, I never saw him take a drink (even though co-star David Hemmings was often pouring). But his behavior was so bizarre that I was certain something was very wrong. With a wild gleam in his eye, O’Toole babbled away in a fashion that was nonsensical even for an actor. He was disconcertingly frail and thin, with hair dyed flame red (it looked much more natural on film), setting off skin so pale it was nearly translucent.

He would pop up for a moment, heave himself into a chair, throw bone-white hands around, smiling at some private joke, and then, just as quickly, disappear again.

I truly believed I was watching the disintegration of a once-great actor–although in fairness as soon as director Martyn Burke’s camera rolled, O’Toole transformed, focused, said his lines effectively and hit his marks.

The piece I wrote about my encounters with O’Toole ended up being blasted across the front page of the New York Post. After that, just about every major paper in the United States and Britain picked up some variation of the story. Peter O’Toole was washed up, dead, finished.

I never heard from O’Toole after the story came out, although I can’t imagine it made him very happy–or maybe he just didn’t care at that point since he seemed barely aware I was present, and if he ever directly answered one question I asked him, I can’t for the life of me remember what it was.

Some time later it was revealed that O’Toole had in fact nearly died that year from a blood disorder brought on by the removal of a large portion of his stomach and pancreas (why he had been forced to stop drinking). In retrospect, it was a wonder he was on his feet, let alone making a movie.

Well, he wasn’t nearly as close to death as I feared. He sailed on, oblivious to naive young reporters prematurely writing his obituary, making at least thirty more films (and lots of television). He was nominated for an Oscar three more times, appeared on stage, wrote two autobiographies (and is said to be working on a third), all the while looking and behaving, as the critic David Thomson observed, “like his own ghost.”

Despite his frailness, the sense of the doomed, elegant scarecrow he often brought to the screen, O’Toole outlived his hard-drinking contemporaries: Burton, his good friend, dead at fifty-eight; Oliver Reed dropping in a Malta pub at sixty-three; Richard Harris gone at seventy-one.

Still, a sense of disappointment clings to any discussion of O’Toole’s career in the wake of his retirement announcement, a feeling that greatness has been missed. He has not been any kind of leading man for many years, showing up for paid gigs to momentarily play ambassadors (The Last Emperor) or kings (Troy, Stardust), or men of the cloth (a pope in The Tudors; a cardinal in TV’s Joan of Arc; a priest in For Great Glory:The True Story of Cristiada), flailing about, effortlessly commanding the screen while tossing off reams of dialogue.

In December, it will have been fifty years since the release of Lawrence of Arabia, his greatest screen achievement and the film for which he will always be remembered–the David Lean masterpiece that started so many of us on what became a lifelong obsession with movies.

If you have starred in one of the great movies of all time, held the screen with such mesmerizing brio for nearly four hours, maybe that’s more than enough for any actor.The rest will barely be conversation.

I still feel guilty about this, but my premature Peter O’Toole death knell went a long way toward establishing me as a magazine writer in the United States. After that story was published, I was able to write for just about everyone, so I owe him a lot.

I’m sorry I killed him off so early. Big mistake, as it turned out. These days, I hear he even allows himself a glass of red wine (a Margaux is favored) or a sip of whisky.

I imagine him sitting around contemplating the Margaux, a twinkle in those riveting blue eyes, smirking with secret delight at how he has fooled everyone–particularly that dumb reporter who killed him off so many years ago.

November 20, 2013

Standing In Dealey Plaza, Thinking . . .

Arriving for the first time at Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, I stood transfixed, thinking, I could have shot President Kennedy.

Arriving for the first time at Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, I stood transfixed, thinking, I could have shot President Kennedy.

Without knowing much of anything about guns, that’s what immediately crossed my mind at the place where President John F. Kennedy was assassinated fifty years ago.

You are astonished by how close everything is, how nestled into a small, convenient triangle for a would-be assassin. It is hard to imagine a more perfect place to shoot a president. Dealey Plaza looked like a movie set for the world’s best known assassination movie.

Any ideas you ever had about conspiracies, the existence of more than one shooter, the Grassy Knoll, actor Woody Harrelson’s father (a convicted killer for a time a favorite of conspiracy theorists) are put to rest standing in Dealey Plaza.

Rather, you shake your head at the innocence of the time, the naïve belief that you could put a popular, charismatic president in an open automobile and send him slowly through the streets of a major U.S. city, and he would be just fine. Innocence ran away that day, and it hasn’t been back since.

Like just about everyone of a certain age, I remember exactly where I was on November 22, 1963: closing a locker on a Friday afternoon at Brockville Collegiate Institute where I was a grade nine student. Something was in the air about President Kennedy. Had he been shot? The rumor ran like a pulse through the school.

The vice principal, a small, mustached education bureaucrat, happened along at that moment. I turned to him and asked, “Mr. Grant is it true the president has been shot?’

And Mr. Grant replied in the impersonal, formal voice of someone who could care less, “Yes, I believe that is the case.” The sound of that toneless bureaucrat’s voice has haunted me for fifty years.

Numb with disbelief, I staggered home and did what everyone else did at the time, I turned on the television. By then the American networks had broken off their regular programming and were broadcasting live.The clear, rumbling baritone of Walter Cronkite confirmed the president was dead.

Dead. In Dallas, Texas. What the blazes was Kennedy doing in Dallas, anyway? I remember thinking. The answers, of course, became painfully evident as the weekend wore on. I don’t think I ever left the television. No one in our family did.

Early Sunday morning, still half asleep, I turned on the TV in time to watch Jack Ruby shoot Lee Harvey Oswald live and in black and white. I was fifteen years old. I could not believe what I was seeing.

Like just about everyone else, I was enthralled with Jack Kennedy, the young, handsome president with the beautiful wife. One tends to forget what a drab, monochromatic time it was–the men wore hats still, the women showed up in white gloves. There was a certain grim formality about everything.

The Kennedys, on the other hand, were in color, vivid, alive, full of energy. The White House in faraway Washington was Camelot, and JFK was its dashing king accompanied by Jacqueline, his glamorous queen.

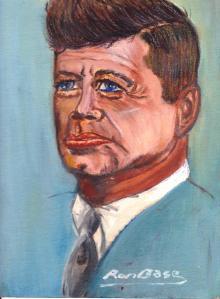

I bought into all of it. A lonely teenage kid in search of a role model in a small Eastern Ontario town had found one in John Kennedy. The Kennedy adventures were chronicled in the pages of Life and Look magazines. I devoured them, and anything else about the Kennedys I could find. Trying my hand at oil painting, my first subject was JFK.

I bought into all of it. A lonely teenage kid in search of a role model in a small Eastern Ontario town had found one in John Kennedy. The Kennedy adventures were chronicled in the pages of Life and Look magazines. I devoured them, and anything else about the Kennedys I could find. Trying my hand at oil painting, my first subject was JFK.

That Friday in 1963, young and oh-so impressionable, I felt like something very personal and close had been taken away. Director Oliver Stone, who made JFK, a goofy but riveting pro-conspiracy movie about the assassination, rightly noted that no matter what you thought about Kennedy’s death, afterwards, nothing was ever the same again.

In the next five years as I left high school to pursue a newspaper career, Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King were assassinated; America, caught up in the horrors of Vietnam, appeared to be going up in flames; and, heaven help us all, Richard Nixon was becoming the most corrupt president in U.S. history.

Through it all, like so many others of my generation, I never shook off my fascination with or admiration for John F. Kennedy, the belief that had he lived, the world would have been a whole lot better.

(The first real criticism I encountered about Kennedy came from David Halberstam, the New York Times reporter who wrote The Best and the Brightest, a lacerating book about the intellectuals and academics of the Kennedy administration who laid the groundwork for America’s catastrophic involvement in the Vietnam war. Reading the book and talking to Halberstam, whom I greatly admired, left me in shock.)

A few years after his death, on a gray, overcast day, accompanied by my mother and brother, I visited Kennedy’s grave at Arlington Cemetery with its eternal flame and Washington spread out in the mist below.

Later, I eagerly stood in line to shake Teddy Kennedy’s hand when he was on the stump for the ill-fated presidential candidacy of George McGovern.

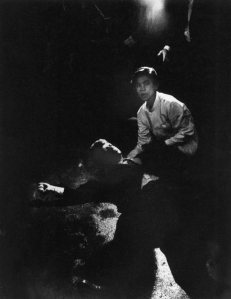

On my first visit to Los Angeles, I stayed at the Ambassador Hotel, home of the legendary Cocoanut Grove nightclub and, more notorious by that time, the place where Sirhan Sirhan shot and killed Bobby Kennedy.

I was having dinner in the Ambassador’s dining room with the late cartoonist, author, and TV personality Ben Wicks, when we got to talking with the hotel manager. It had not occurred to us until then that we were feet away from the spot where Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated. The manager led us back to the kitchen.

It was late, and the kitchen was deserted. A single light shone through the dimness illuminating the floor where Bobby had fallen that June night in 1968. Nothing in the kitchen marked the spot. It was the forgotten assassination site.

It was late, and the kitchen was deserted. A single light shone through the dimness illuminating the floor where Bobby had fallen that June night in 1968. Nothing in the kitchen marked the spot. It was the forgotten assassination site.

As soon as I got to Dallas on a cold February day, I hailed a cab and drove to Dealey Plaza. The Texas School Book Depository, where Oswald had shot Kennedy from a sixth story window, was closed for renovations. I found a position on the grassy knoll overlooking Elm Street and gazed at the spot where Kennedy had been shot.

The moment was overwhelming. For a boy of fifteen, the death of the president seemed surreal and impossible. As an adult standing in the reality of Dealey Plaza, it seemed even more surreal and more impossible.

Now all these years later, remembering that day and the boy closing a locker at a high school in a small Ontario town, one still can’t help but think of impossibilities, of hopes shattered, and dreams unfulfilled, about how far from Dallas we have come and yet how close it all remains.

Still standing in Dealey Plaza. Thinking…

November 6, 2013

“I’m Getting A Pulse”: My Brilliant (Acting) Career

[image error]Now that awards season is upon us–an Oscar to Robert Redford for his incredible performance in All Is Lost; take the statuette Cate Blanchett for what you accomplished in Blue Jasmine–it is time to reveal the unsung details of my brilliant acting career.

Discussions of my acting career are hampered by the fact that most people are unaware I had an acting career. This is probably just as well, the brilliance of my performances, to say the least, being somewhat in doubt.

Anyone who is ever involved in film at one time or another entertains fantasies about being up there on the big screen. For many years, my fantasy involved a tall, rugged loner astride a horse, not saying much, charismatic nonetheless, and, of course, irresistible to women. In short, I saw myself as a movie star.

Someone like, well, someone like Robert Redford.

(Not to pause for a commercial here, but in my new novel The Two Sanibel Sunset Detectives, that same movie star fantasy haunts our hero, Private Detective Tree Callister. Hmmm. I wonder who gave him that idea?)

(Not to pause for a commercial here, but in my new novel The Two Sanibel Sunset Detectives, that same movie star fantasy haunts our hero, Private Detective Tree Callister. Hmmm. I wonder who gave him that idea?)

As it turned out, the most accurate part of my fantasy–the warning I should have heeded–was the part about being silent. My problems as an actor began as soon as I opened my mouth.

Thankfully, the first time I was in a movie, I didn’t have to do much more than groan–and I had problems doing that convincingly.

In Heavenly Bodies, a movie I also had a hand in writing, I was one of a number of professional football players sent to the workout club that figures in the story, ordered to get into shape.

“You don’t look like much of a football player to me,” said the wardrobe woman, eyeing me up and down. She then handed me a pair of athletic wristbands. “What are these for?” I asked. “They’re to make your wrists look thicker.” Ever since, not a day goes by that I don’t look at my wrists and fret that they are too thin.

The scene I was in takes place at the point in the story where the petit young women running the club (called Heavenly Bodies) put the players through such a grueling workout that they end up collapsed on the floor in exhaustion. The scene would give our heroine (played by Cynthia Dale in her first film role) a chance to meet our football-playing hero.

When the time came to film the scene, us players all writhed and heaved away. As I writhed and heaved, it struck me that it looked as if I was writhing and heaving. It didn’t look as if any of us was the least bit tired.

Sure enough. When the scene appeared on the big screen, it looked as though we were writhing and heaving. It did not look as though we were exhausted. The worst writher and heaver in the bunch–and the least convincing–was me.

What’s more, my wrists looked awfully thin.

My next movie role featured me as an emergency room doctor, blessedly hidden behind a surgical mask, in the thriller White Light, another of the masterpieces I was guilty of writing. This time I had dialogue–the last thing, as it transpired, I should have been given.

It is at the end of the story, and we are in a hospital emergency room where the hero (Martin Kove of TV’s Cagney and Lacey) reacts to the fact that the heroine whom he has been chasing throughout the movie (played by a lovely actress named Allison Hossack), has just been brought back to life.

I’m supposed to signal this turn in the plot by looking at a monitor and announcing, “I’m getting a pulse!”

I wrote the line so I’ve got no one else to blame.

The night we shot the scene, I duly made the announcement, “I’m getting a pulse” with such seeming expertise that once again I began to think in terms of an acting career. I imagined myself strong and silent and rugged astride a horse. Not saying much, maybe “I’m getting a pulse,” once in a while.

Then we got into the editing room. Every time the editor ran that scene, my reading of “I’m getting a pulse,” seemed all wrong. Since it was the finale of the film, I didn’t see why any dialogue was necessary. I begged for my line to be drowned out by swelling music. No one paid any attention.

The premiere of White Light was held at the old Hollywood Theatre in Toronto, a vast auditorium filled that night with invited guests eager to see what we had produced. I arrived with my mother, and all I could think of was, “I’m getting a pulse.”

For the first hour and twenty minutes, the audience remained respectfully silent and attentive as the mystery unfolded on the screen. Then came the grand finale, the moment when Allison is being revived so she can live happily ever after with Marty Kove. The camera came in on me, I looked up at the monitor and said, “I’m getting a pulse!”

The whole theatre roared with laughter.

[image error]Of all the embarrassments one can suffer in a lifetime–and goodness knows I’ve had more than my share–nothing quite matches the experience of a theater packed with people heaving with unintentional laughter at a line you’ve just said twenty feet high on a movie screen. You want to run away screaming (“I’m getting a pulse!”) and hide, but you can’t. There is no escape. You are trapped.

The movie opened a week or so later, and I’m beginning to think, well, maybe my reading of that line wasn’t so bad after all. Maybe the audience reaction was merely the release of pent-up tension built up as the crackerjack plot (written by you-know-who) unfolded.

By the time Saturday rolled around, I had decided that my performance was fine. There could still be a future movie star in the making here, all I had to do was reassure myself one last time.

Late that night I walked over to the Uptown Theatre where White Light was playing. As I took my seat, I saw that the auditorium was nearly empty. A few stray souls with nothing better to do on a Saturday night. Still, the movie unfolded smoothly enough, and the meager audience seemed attentive. All appeared to be well. I began to relax.

Then came the finale: Marty took Allison’s hand and looked soulfully into her eyes, willing her back to life. Cut to a close-up of me looking up at the monitor and saying, “I’m getting a pulse!”

The small audience inside the Uptown screamed with laughter.

I reeled outside. The cold night air hit me. As I stood in front of the Uptown taking deep, gulping breaths, my brilliant acting career was at an end. I stared down helplessly at my thin wrists, crying out, “I’m getting a pulse!”

On the silent, empty street, finally, nobody laughed.

“I’m Getting a Pulse”: My Brilliant (Acting) Career

[image error]Now that awards season is upon us–an Oscar to Robert Redford for his incredible performance in All Is Lost; take the statuette Kate Blanchett for what you accomplished in Blue Jasmine–it is time to reveal the unsung details of my brilliant acting career.

Discussions of my acting career are hampered by the fact that most people are unaware I had an acting career. This is probably just as well, the brilliance of my performances, to say the least, being somewhat in doubt.

Anyone who is ever involved in film at one time or another entertains fantasies about being up there on the big screen. For many years, my fantasy involved a tall, rugged loner astride a horse, not saying much, charismatic nonetheless, and, of course, irresistible to women. In short, I saw myself as a movie star.

Someone like, well, someone like Robert Redford.

(Not to pause for a commercial here, but in my new novel The Two Sanibel Sunset Detectives, that same movie star fantasy haunts our hero, Private Detective Tree Callister. Hmmm. I wonder who gave him that idea?)

(Not to pause for a commercial here, but in my new novel The Two Sanibel Sunset Detectives, that same movie star fantasy haunts our hero, Private Detective Tree Callister. Hmmm. I wonder who gave him that idea?)

As it turned out, the most accurate part of my fantasy–the warning I should have heeded–was the part about being silent. My problems as an actor began as soon as I opened my mouth.

Thankfully, the first time I was in a movie, I didn’t have to do much more than groan–and I had problems doing that convincingly.

In Heavenly Bodies, a movie I also had a hand in writing, I was one of a number of professional football players sent to the workout club that figures in the story, ordered to get into shape.

“You don’t look like much of a football player to me,” said the wardrobe woman, eyeing me up and down. She then handed me a pair of athletic wristbands. “What are these for?” I asked. “They’re to make your wrists look thicker.” Ever since, not a day goes by that I don’t look at my wrists and fret that they are too thin.

The scene I was in takes place at the point in the story where the petit young women running the club (called Heavenly Bodies) put the players through such a grueling workout that they end up collapsed on the floor in exhaustion. The scene would give our heroine (played by Cynthia Dale in her first film role) a chance to meet our football-playing hero.

When the time came to film the scene, us players all duly writhed and heaved on the floor. As I writhed and heaved, it struck me that it looked as if I was writhing and heaving. It didn’t look as if any of us was the least bit tired.

Sure enough. When the scene appeared on the big screen, it looked as though we were writhing and heaving. It did not look as though we were exhausted. The worst writher and heaver in the bunch–and the least convincing–was me.

What’s more, my wrists looked awfully thin.

My next movie role featured me as an emergency room doctor, blessedly hidden behind a surgical mask, in the thriller White Light, another of the masterpieces I was guilty of writing. This time I had dialogue–the last thing, as it transpired, I should have been given.

It is at the end of the story, and we are in a hospital emergency room where the hero (Martin Kove of TV’s Cagney and Lacey) reacts to the fact that the heroine whom he has been chasing throughout the movie (played by a lovely actress named Allison Hossack), has just been brought back to life.

I’m supposed to signal this turn in the plot by looking at a monitor and announcing, “I’m getting a pulse!”

I wrote the line so I’ve got no one else to blame.

The night we shot the scene, I duly made the announcement, “I’m getting a pulse” with such seeming expertise that once again I began to think in terms of an acting career. I imagined myself strong and silent and rugged astride a horse. Not saying much, maybe “I’m getting a pulse,” once in a while.

Then we got into the editing room. Every time the editor ran that scene, my reading of “I’m getting a pulse,” seemed all wrong. Since it was the finale of the film, I didn’t see why any dialogue was necessary. I begged for my line to be drowned out by swelling music. No one paid any attention.

The premiere of White Light was held at the old Hollywood Theatre in Toronto, a vast auditorium filled that night with invited guests eager to see what we had produced. I arrived with my mother, and all I could think of was, “I’m getting a pulse.”

For the first hour and twenty minutes, the audience remained respectfully silent and attentive as the mystery unfolded on the screen. Then came the grand finale, the moment when Allison is being revived so she can live happily ever after with Marty Kove. The camera came in on me, I looked up at the monitor and said, “I’m getting a pulse!”

The whole theatre roared with laughter.

[image error]Of all the embarrassments one can suffer in a lifetime–and goodness knows I’ve had more than my share–nothing quite matches the experience of a theater packed with people heaving with unintentional laughter at a line you’ve just said twenty feet high on a movie screen. You want to run away screaming (“I’m getting a pulse!”) and hide, but you can’t. There is no escape. You are trapped.

The movie opened a week or so later, and I’m beginning to think, well, maybe my reading of that line wasn’t so bad after all. Maybe the audience reaction was merely the release of pent-up tension built up as the crackerjack plot (written by you-know-who) unfolded.

By the time Saturday rolled around, I had decided that my performance was fine. There could still be a future movie star in the making here, all I had to do was reassure myself one last time.

Late that night I walked over to the Uptown Theatre where White Light was playing. As I took my seat, I saw that the auditorium was nearly empty. A few stray souls with nothing better to do on a Saturday night. Still, the movie unfolded smoothly enough, and the meager audience seemed attentive. All appeared to be well. I began to relax.

Then came the finale: Marty took Allison’s hand and looked soulfully into her eyes, willing her back to life. Cut to a close-up of me looking up at the monitor and saying, “I’m getting a pulse!”

The small audience inside the Uptown screamed with laughter.

I reeled outside. The cold night air hit me. As I stood in front of the Uptown taking deep, gulping breaths, my brilliant acting career was at an end. I stared down helplessly at my thin wrists, crying out, “I’m getting a pulse!”

On the silent, empty street, finally, nobody laughed.

October 17, 2013

Bobby Orr, Me, and the Mystery of Alan Eagleson

The release this week of Bobby Orr’s autobiography, My Story, and his extended appearance on CBC-TV’s The National, brought back memories of a long-ago encounter with Orr and Alan Eagleson, the notorious agent and promoter and one-time close friend who made the hockey great and then betrayed him.

The release this week of Bobby Orr’s autobiography, My Story, and his extended appearance on CBC-TV’s The National, brought back memories of a long-ago encounter with Orr and Alan Eagleson, the notorious agent and promoter and one-time close friend who made the hockey great and then betrayed him.

It was an encounter that saved my professional life at a moment when it badly needed saving–but that to this day still leaves me mystified.

Orr hasn’t said much about Eagleson over the years, but during his interview with Peter Mansbridge, he spoke about how his former lawyer and friend (“he was like a brother”) ruined him financially. “Shame on him,” Orr said. “Just, shame on him.”

And, as Orr pointed out, it wasn’t just him. Eagleson defrauded other players who were his clients, and skimmed funds from the NHL Players’ Association, among other criminal acts that in 1994 resulted in thirty-four charges of embezzlement, fraud, and racketeering.

He eventually pleaded guilty to three counts of embezzlement and fraud and spent six months in jail. He ended up disgraced and disbarred, stripped of his Order of Canada, and forced to resign from the Hockey Hall of Fame.

All of this was very much in the future when I met him. At that point, he was the most powerful man in hockey–the head of the newly formed NHL Players’ Association as well as the top agent for players in the league. He was also a force in Conservative Party politics, and, thanks in large part to his work organizing the 1972 Summit Series between Canada and Russia, something of a homegrown hero, one of the best known and most popular figures in the country.

This was the guy who was about to change my life.

While Alan Eagleson flowered at the top, I was hovering near the bottom. I had left the newspaper business to fulfill an ambition to be a freelance magazine writer. It had not gone particularly well–assignments had fallen through, and, most troubling, a story about Jack Cole of Coles Book Stores for The Canadian got spiked (although, curiously enough, the magazine later ran the piece pretty much as I had written it, but without a byline).

My wife at the time, Lynda, and I were raising two small children, there was a mortgage to pay, and not a lot of money coming in. I was frankly worried about my future when I went to see Nick Steed at Quest Magazine.

Nick was as tough and sophisticated an editor as I’d ever encountered. I suspect it was Nick’s idea to do a piece on Alan Eagleson. I silently gulped. What I knew about hockey amounted to a sneaking suspicion it was played on ice. Nonetheless, that was the assignment. And I had only two weeks to do it. “If I like the piece, you’ll always have work at this magazine,” Nick said. “If I don’t like it, you’ll never work here again.”

I staggered out of his office, convinced I was finished. This was an opportunity that was no opportunity at all. I wasn’t certain I could get in touch with Alan Eagleson let alone get him to agree to talk, all within two weeks.

As it happened, I had briefly met Eagleson, and my wife had encountered him a number of times in connection with her job at The Toronto Sun.

That was my only edge as I rang his office the next morning. To my surprise, he took my call right away. He said he remembered me, and he certainly remembered Lynda. I explained that Quest Magazine wanted me to do a profile.

“How soon do you need it?” he asked.

“I need it right away,” I said. “I’m in a bit of a jam here.”

“Come on over,” he said.

“Right now?” I said, shocked.

“Right now,” he said. “Get over here.”

I hurried to his office and was ushered in. Eagleson was in shirtsleeves behind his desk, a tall man with dark hair and aviator-style glasses, a rock jaw, and the sort of hail-fellow-well-met demeanor that lit up the room.

He almost immediately made you feel like you were his best friend and closest confidant. He exuded a warmth that was irresistible. It was easy to see how he could seduce young hockey players–even young magazine writers desperate for a story.

We sat in his office for an hour or so talking generally about this and that, then he suggested we adjourn to his Rosedale home. When I arrived, I found him out by the pool. We sat together and we talked through the afternoon, about how unfair hockey had been to its players before he came along and began negotiating for them, starting with Bobby Orr, and how much he had done to improve the average player’s lot.

As naïve as I was about hockey and as enthralled by my host as I was, it did strike me that the guy who headed the Players’ Association might be at odds with the guy who was an agent for individual players. That guy in effect would have to wear two hats at the same time when it came to dealing with team owners. Wasn’t that a conflict of interest?

Eagleson smoothly dismissed the notion. There was no conflict as far as he was concerned, and, at that point, no one was asking too many questions or raising objections to the arrangement. Alan Eagleson was good for the game of hockey, its players and owners–the golden boy with the twinkle in his eye and the reassuring smile.

That smile only widened when the door opened and out came Bobby Orr, legendary number four himself, who by then had left the Boston Bruins and was playing for the Chicago Blackhawks.

That smile only widened when the door opened and out came Bobby Orr, legendary number four himself, who by then had left the Boston Bruins and was playing for the Chicago Blackhawks.

Orr was accompanied by Paul Henderson, famous for having scored the winning goal in 1972 against Russia in game eight of the Summit Series. Henderson was playing for the Toros of what was then the World Hockey Association.

Delighted by these unexpected arrivals, Eagleson decided to move us all inside. We sat around his living room and the three friends talked shop and traded gossip, enjoying each other’s company late on a summer afternoon.

I felt a trifle uneasy sitting listening to the two biggest stars in hockey carry on. Even though Eagleson had quickly introduced me, he had not said who I was and what I was doing there. The two players never asked.

Finally, Eagleson, the gleam in his eye turning mischievous, announced that I was a journalist doing a story. Henderson seemed to take it in stride. But Bobby Orr appeared taken aback by the revelation. Nonetheless, both players smiled gamely, made the right jokes, and continued with their conversation.

Still, it was getting late, and the two soon departed, leaving Eagleson and I alone. As he walked me out, he wanted to make sure I had enough for my story. I said I had more than enough.

We shook hands, I thanked him for his generosity, and said goodbye. I then raced home and hammered out the piece as fast as I could. Nick Steed loved it. The Eagleson story went on to be nominated for a national magazine sports writing award, a particular irony for a writer as sports challenged as I am.

True to his word, Nick kept me working steadily for the next three years. What’s more, my freelance magazine writing career turned around, and I ended up writing for everyone under the sun in Toronto and New York. I doubt any of it would have happened if Alan Eagleson hadn’t come to my rescue.

As the years went by and the accusations of fraud against Eagleson piled up, I often revisited that afternoon with him. I went back to it not only to inspect my own gullibility, and to understand more about the limits of celebrity profiles, but also to ask myself over and over again: why?

Why would a man capable of such duplicity and deception open himself up the way Eagleson did? Why would he drop everything, take a complete stranger into his home and make himself so available? Why was Alan Eagleson, who in so many complicated ways turned out to be not a nice guy, such a nice guy?

Ego? I doubt it. Eagleson needed another reporter writing about him like he needed a hole in the head. He had everything to hide, and yet he hid nothing or seemed to hide nothing that afternoon. But then again, appearances are deceiving, and maybe that’s the answer to the riddle: perhaps Eagleson had decided long before I came along that hiding in plain sight was the best camouflage of all.

Whatever it was, that time with Alan Eagleson changed my professional life. For that, I will always be grateful to him.