Ron Base's Blog, page 10

May 10, 2016

Cannes, El Sid, and Six Green Beans

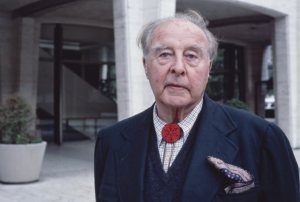

Every year about this time I think of Cannes, El Sid, and six green beans.

El Sid was my nick-name for Sid Adilman, the legendary Toronto Star entertainment reporter. For years in May, El Sid and I would head for the Cannes International Film Festival, the longest-running, biggest, and most glamorous of movie gatherings.

Cannes had something no other festival will ever be able to match: the Mediterranean and the French Riviera. When I was growing up, the Côte d’Azur bespoke the ultimate in sophistication, personified, to my mind, by Cary Grant and Grace Kelly in Alfred Hitchcock’s classic To Catch A Thief. Once I saw Cary and Grace against that breath-taking backdrop, I had to get there, somehow.

To my surprise, when I finally did arrive, the reality of Cannes more or less lived up to my childhood fantasy.

In 1981 the festival was still a somewhat intimate affair, although I’m not sure I realized it at the time. You could become stranded at Charles De Gaulle airport in Paris with Norman Mailer. Jerry Lewis would stroll past you on the Croisette and nod good morning.

At a reception a tall stranger would walk over and it would take a moment to realize with a start you were chatting to Gore Vidal, a friend of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward who would arrive a few moments later.

The main festival was still housed in the Palais next door to the Hotel Carlton, tiny compared to the monstrosity being constructed further along the Croisette overlooking the Bay of Cannes.

The life of the festival was more or less defined between the Hotel Carlton to the east and the Hotel Majestic to the west.

The life of the festival was more or less defined between the Hotel Carlton to the east and the Hotel Majestic to the west.

The terrace at the Carlton constituted the festival epicenter in those days. Anyone who was anyone sat there, mingling with lots of people who were nobodies, but then the terrace was a fairly democratic place. If you were there, you might be somebody. And if you weren’t, well, who was to know?

Sid and I always stayed at the Hotel du Century up the street from the Carlton on the rue d’Antibes. Not a luxury hotel by any stretch, but the rooms were good-sized and fairly reasonably priced–if there was such a thing as reasonable in Cannes during the festival.

This was our headquarters each year. This is where we drove each other crazy.

It was often said that El Sid and I were an odd couple. He was a small, slim, intense man, always impeccably dressed, always on the hunt for a double espresso, forever staring into patisserie windows at sweets he would never eat.

Everyone in show business read Sid’s daily Eye On Entertainment column in the Toronto Star. He was Canada’s premier show business reporter (the fact that he was also the Canadian editor of Variety, the Hollywood trade publication, only added to his influence).

No one took their beat more seriously than El Sid. He lived and breathed entertainment. I had been reading him since high school in the days when he was at the old Toronto Telegram. When we first met, I was somewhat in awe–and secretly thrilled to be sharing reporting duties at the festival.

At least I was the first year. After that, I decided that life on the Mediterranean was too short to spend sitting in a movie theatre.

The great Dusty Cohl, one of the founders of what is now the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), daily held court on the Carlton terrace wearing his trademark black cowboy hat.How could you resist him? The soupe de poisson in the Old Town was delicious, the Kir Royales late at night at the Majestic, irresistible.

The fun of Cannes was not, alas, in the movie theatres. It was at the Hotel du Cap at Eden Roc in Antibes, not far from Cannes. The really rich and the very famous were housed in the one hundred rooms of this converted mansion (built by a Russian prince).

Here, one could inhale the sweet fragrance of the hotel’s roses while lounging near the pool with the actress Mary Steenburgen and her then-husband Malcolm McDowell, sweating from an afternoon tennis match.

The fun was at Le Petit Carlton on the rue d’Antibes, the anthesis of the Carlton terrace, where the press and the indie filmmakers hung out, and where you could end up drinking (fairly cheap) beer with Terry Jones of Monty Python or rubbing shoulders at the bar with director Jim Jarmusch.

It was dining at the Moulin des Mougins, the first Michelin three star restaurant I ever visited, where the diner sitting next to you could turn out to be the great actor James Mason.And it was dancing late at night to a live Chet Baker concert in a ballroom at the Hotel Majestic.

The movies at Cannes could always be screened back in Toronto, but the experience of Cannes, I decided, would never be repeated, and so I had better enjoy it. This attitude infuriated Sid. He was there to work. If I missed the screening of Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence–which I did–he became apoplectic.

Each year, without fail, he stopped talking to me. I would line up for a screening (yes, I did go to them on occasion), and there would be El Sid standing not ten feet away. Ignoring me.

But Sid was nothing if not basically good-hearted, and no matter how angry he got with me, he always came around in the end, and, as unlikely as we were together, we remained friends. But he was a character. Of all the stories I can tell about Sid, this is my favorite:

On the Air Canada flight bound for Paris, I settled back in my seat, relieved to finally be off to the festival, looking forward to ten days on the Côte d’Azur. I ordered a nice glass of Merlot from the flight attendant. Dinner arrived (in those days Air Canada still served a pretty decent meal on its transcontinental flights). I glanced over at Sid, who was sitting next to me. He wasn’t eating anything.

Eventually, he produced a tin foil-wrapped package and placed it on his lowered chair back table. He then proceeded to unwrap the tin foil.There, laid out in a neat row, were six green beans.

“My dinner,” he announced testily when I asked him about the beans.

Oh.

Sid proceeded to eat four of the beans, picking up one at a time, placing it in his mouth, chewing it thoroughly, before attacking the next one.

With two green beans left, he abruptly stopped eating, carefully refolded the foil, and put it away. I looked at him. “What was wrong with those two?” I asked.

“I’m saving them for later,” he snapped.

Oh.

Since those days, I’ve been back to the South of France many times and even returned to Cannes on a few occasions. The original Palais has long since closed and the new, much more grand version across from the Majestic has shifted the festival focus away from the Carlton.

Since those days, I’ve been back to the South of France many times and even returned to Cannes on a few occasions. The original Palais has long since closed and the new, much more grand version across from the Majestic has shifted the festival focus away from the Carlton.

The Hotel du Century where Sid and I stayed was closed for years, serving as a drab, deserted repository for my fading Cannes memories. Now it has been renovated into a fashionable boutique hotel and made unrecognizable.

The Carlton also has undergone a facelift  that has robbed it of its former Old World charm or any sense that Grace Kelly and Cary Grant might stroll through the lobby. Le Petit Carlton closed in 2008, and the space it occupied is now just another one of the many high-end boutiques lining rue d’Antibes.

that has robbed it of its former Old World charm or any sense that Grace Kelly and Cary Grant might stroll through the lobby. Le Petit Carlton closed in 2008, and the space it occupied is now just another one of the many high-end boutiques lining rue d’Antibes.

The Moulin des Mougins famously lost one of its stars and much of its luster. The Hotel du Cap still attracts the very famous who these days must be really, really rich to stay there (and you still pay in cash).

And the festival endures of course, but one has the impression, viewing it from afar, that it is much bigger, more regimented, and certainly less intimate than it was when I was there. But maybe that’s just me.

El Sid, wonderful, exasperating Sid, died too soon in 2006 at the age of sixty-eight. But each year as the film festival gets under way, I sit and remember those wild, silly years when we traveled together, and fought together, and, on more than a few occasions, laughed together.

And I smile.

April 22, 2016

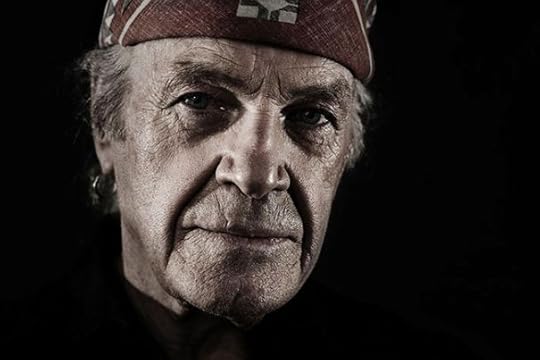

Don Francks: A Star Was Born Again, and Again–and Again

When I finally met Don Francks it was on the set of a movie I wrote titled First Degree. Not that I had much influence, but as one of the producers, I lobbied hard to cast Don in the role of a powerful entrepreneur confronting the movie’s conniving detective played by Rob Lowe.

It wasn’t a large part, but to my delight Don accepted. He had fascinated me since I was a kid growing up in a small Ontario town, yearning to break out. Don Francks was Canadian, a charismatic performer, blessed with an impressive jaw, an impish smile, a raspy, easy singing voice, dancing ability, and great presence.

Don Francks was going to be a star.

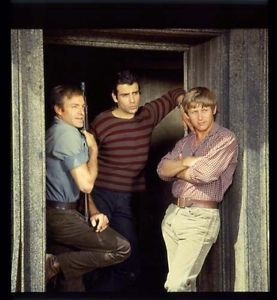

His star was to be born on Broadway in a lavish musical production called Kelly, about a man who jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge and survived. Backed by big name producers David Susskind and Joseph Levine, directed by Herbert Ross, the musical was one of the most expensive productions in Broadway history when it opened in 1965. Don had never appeared on a Broadway stage, but as soon as the producers auditioned him, he was immediately signed for the lead.

Less than a year later, Kelly closed after a single performance; a colossal failure of legendary proportions.

But Don Francks was going to be a star.

He was going to be a star on television in a big-budget Mission Impossible-inspired series, called Jericho, about an elite intelligence team operating behind German lines during World War II. Don was the team leader. The series lasted sixteen episodes before it was cancelled.

He was going to be a star on television in a big-budget Mission Impossible-inspired series, called Jericho, about an elite intelligence team operating behind German lines during World War II. Don was the team leader. The series lasted sixteen episodes before it was cancelled.

He was going to be a star in Finian’s Rainbow, director Francis Ford Coppola’s lavish adaptation of the Broadway hit that co-starred British pop star Petula Clark and Fred Astaire, in what turned out to be his last movie musical. Don played Woody, the movie’s necessary love interest. He and Petula Clark had great onscreen chemistry, particularly when they sang “Old Devil Moon.”

But Finian’s Rainbow bombed at the box office, one of the great musical failures of the era. That was all right. Don Francks was going to be a star…

Except he wasn’t.

Don retreated north, back to his native Canada with his wife, Lili. For a time, he left show business altogether and became Iron Buffalo, living on a First Nations reserve, a long, long way from Broadway and Hollywood. He said he was fed up with American politics and the Vietnam War—and maybe, just maybe, tired of the struggle to become something for which he had little taste.

I watched all this from a distance, a kid avidly reading about Don, watching with delight his appearances on Johnny Carson’s Tonight show, Johnny’s go-to counterculture guy, reading inspired musings from his journals. I rooted for his success, certain that the failures had nothing to do with his talent, which no one ever doubted, but were the result of extraordinary bad luck, the gods merrily playing games with Don’s destiny, allowing him tantalizingly close to stardom then pulling it away at the last moment.

By the time I encountered him on the set of First Degree, the years of his American stardom were faded memory. He was known as a hard-working Canadian actor, accomplished jazz musician (I had seen him perform several times at George’s Spaghetti House in Toronto), a voice-over artist (for many cartoon shows)—in short, a jack-of-all-artistic trades.

I imagine his role in First Degree was just another gig for him, a few days’ work before going on to something else.

He certainly wasn’t all that happy when I found him in his trailer and nervously presented him with the totally rewritten monologue he was to deliver in a couple of hours. After we shook hands, and I showed him the rewritten pages, he gave me a dark look that suggested what he was probably thinking: “What kind of a##hole are you that you can’t get it right?”

He quickly pulled himself together, his hard eyes softened somewhat, and he said he would do his best. He certainly did.

On the set of a dinner party scene his character was hosting, Don, who, with his trademark headband and ponytail was the personification of Old Hippy, this day looked every inch the rich, powerful mogul he was portraying. Berating Rob Lowe as the detective who would stop at nothing to rise above his social status, Don delivered the rewritten lines flawlessly, making them sound a whole lot better than they ever would have had anyone else said them.

Between takes, we sat and talked, and he warmed considerably, perhaps understanding I was genuinely interested in where he had been and how he had gotten from there to here.

A year or so later, trying to get another production off the ground, I again insisted on Don for a co-starring role. He agreed to drop around to the production office for a chat about the part he was to play. When he got there, he recognized me from our last encounter, gave a rather cynical smile and said, “Are you going to pay me this time?”

I joked that he probably got more for First Degree than I did. Again, he softened and we sat around for an hour or so, relaxed, shooting the breeze, talking about the role. He drifted away and that was that. The movie, as is so often the case, never got made. I never saw Don again.

The news of his death at the age of eighty-four, hit me harder than I expected. I went looking for his obituary in the New York Times. He was at least a fascinating bit of unlikely American cultural history; the Times surely would take note. There were a couple of familiar names in the obit section. The paper reported the death of Fred Hayman, the Rodeo Drive boutique owner who, when I came calling, wondered aloud why I didn’t consider getting a haircut.

Anne Jackson, dead at ninety, rated final words., the actress-wife of the late Eli Wallach, who once told me that she wished her husband hadn’t taken all those roles in spaghetti westerns.

But there was nothing about Don Francks. The Toronto Star didn’t run anything that I could see, either (although the Globe and Mail, thanks to the wonderful Susan Ferrier MacKay, published a long remembrance).

The star who was born again, and again—and again, had died little remembered, except by a few of us who cherished his talent and remembered how well, at the last moment, he learned his lines.

February 29, 2016

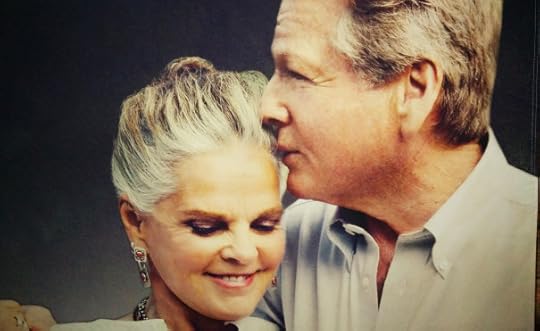

Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal: Falling in Love Letters

Before the other night, the last time I saw Ryan O’Neal was on an elevator at Toronto’s Park Plaza Hotel. He was accompanied by his daughter, Tatum O’Neal, Helga Stephenson, at the time the Toronto film festival’s director of communications, and longtime pal, Lee Majors, television’s Six Million Dollar Man.

As the elevator reached the ground floor, Lee turned to Ryan to say goodbye. “By the way,” he said, “when you get to L.A., do me a favor and look up Farrah. Make sure she’s all right.”

Farrah, of course, was Farrah Fawcett-Majors, at the time Lee’s wife. Ryan did as his pal asked. Farrah and Ryan promptly fell in love, and the rest is a certain amount of tabloid-fed show business history.

![erichsegal[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1456839761i/18283185.jpg) Until then, Ryan O’Neal’s central claim to fame was Love Story, the literary and movie phenomenon of 1970. The film and the subsequent bestselling novel were both written by a Harvard professor, Erich Segal. I got to know Toronto author and journalist Merle Shain who had once dated Segal. She told me that at one point in their relationship, before he wrote the book, they had a terrible fight. Segal phoned to apologize. “Erich,” Merle responded, “love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

Until then, Ryan O’Neal’s central claim to fame was Love Story, the literary and movie phenomenon of 1970. The film and the subsequent bestselling novel were both written by a Harvard professor, Erich Segal. I got to know Toronto author and journalist Merle Shain who had once dated Segal. She told me that at one point in their relationship, before he wrote the book, they had a terrible fight. Segal phoned to apologize. “Erich,” Merle responded, “love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

The rest is, well, more show business history.

In my life as a journalist, I never encountered Ali MacGraw. She blazed so brightly and was extinguished so quickly, but she left a generation of young men, myself included, slightly dazed and not a little lovesick in the wake of her appearances in Goodbye, Columbus and Love Story.

So when it was announced that O’Neal and his Love Story co-star were appearing in a road show production of Love Letters, A.R. Gurney’s enduring two-hander, I had more than passing interest.

Hand-in-hand on a recent Saturday night, Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal came onto the stage at the Barbara B. Mann Performing Arts Hall in Fort Myers, Florida. Iconic Jenny and Oliver are long gone. She is seventy-seven (her birthday is April 1); on April 20 he turns seventy-five.

The coltish beauty who married movie mogul Robert Evans and then ran off with Steve McQueen when they made The Getaway together, resembles someone’s elegant grandmother, still slim, her gray-streaked hair pulled back into a bun.

O’Neal, the California kid who started out as a boxer before movie stardom and a whole lot of unpleasant headlines involving children on drugs and the death of Farrah Fawcett, has put on weight and a pair of glasses. Now he could play the Ray Milland part of the wealthy father in Love Story.

This night they are Melissa and Andrew, not so far from Jenny and Oliver, except this time she is rich and he is not so rich. Seated at a table on a bare stage they face the audience and read the letters addressed to each other over a tempestuous fifty-year friendship. MacGraw is still the free spirit, goading and poking at the preppy O’Neal through two lives swerving from childhood to college and careers, marriages and divorces, success and failures, the two of them alternately fighting to be together and to stay apart. Are they friends or lovers—or both?

Gurney’s play inhabits a stylish fantasy land wherein the participants have money, go to Ivy League schools, pursue interesting careers, and in an age when no one writes such things, manage to write letters that are often more like smart volleys in an ongoing tennis match.

Reading back and forth seated on a stage is not generally regarded as the way to keep modern audiences mesmerized. But somehow Love Letters works a certain magic, aided by Gurney’s wit and restrained sense of pathos and also by surprisingly fine performances from the two stars. As much as we all loved Ali MacGraw in her brief heyday, she was never much of an actress. By the time the producers of Love Letters came knocking, she had long since retired to Santa Fe, New Mexico to pursue her interest in yoga and put acting behind her.

However, on stage in Fort Myers she delivers a delightfully natural and nuanced performance as a brittle, witty young women spinning into middle age and beyond, battered along the way by alcohol abuse and bad marriages.

O’Neal, as he did in Love Story, must carry much of the emotional load, and he does this exceedingly well as the conservative college jock growing into prosperity, the law, and, eventually, the U.S. senate, all the while trying to put the love of his life behind him—discovering he can’t quite do it. He must forever write her one more letter.

As Love Letters unfolds over the course of an hour and a half, it evokes a series of emotions and memories, thoughts of loves won and lost, of time passing—the young man encountering the movie star on an elevator; a fragile Merle Shain fondly recalling how she inadvertently provided the catch phrase that has long outlived her.

At the end, there is a damnable but unavoidable catch in the throat, the emotion you swear you are going to avoid, but that you can’t as Ali and Ryan take their bows and then, shamelessly playing to audience expectations, kiss before exiting, wrapped in each other’s arms.

You leave the theatre, walking into a cooling Florida night, hugging the co-star of your own love story a little more closely.

January 31, 2016

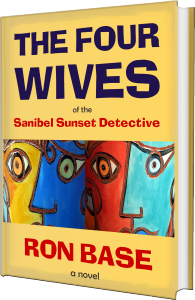

The Four Wives Book Tour Continues…

A new year, a new Sanibel Sunset Detective mystery…The Four Wives of the Sanibel Sunset Detective Book Tour 2016 is off and running. Here are a few of the locations where author Ron Base will be appearing. Check ronbase.com for more updates.

Franklin Shops—Friday, Feb. 5, 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. 2200 First St., Fort Myers.

Bailey’s General Store—Sunday, Feb. 7. From 10 a.m. 2477 Periwinkle Way, Sanibel Island.

Fort Myers International Airport—Monday and Tuesday, Feb. 8 and 9. From 10 a.m. At Coastal News on the main concourse.

Annette’s Book Nook—Wednesday and Thursday, Feb. 10 and 11, 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Santini Mall, Estero Blvd., Fort Myers Beach.

Adventures in Paradise—Friday, Feb. 12. From 11 a.m. 2019 Periwinkle Way, Sanibel Island.

Bailey’s General Store—Saturday, Feb. 13. From 10 a.m. 2477 Periwinkle Way, Sanibel Island.

Annette’s Book Nook—Wednesday and Thursday, Feb. 17 and 18, 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Santini Mall, Estero Blvd. Fort Myers Beach.

MacIntosh Books—Friday, Feb. 19. From 10 a.m. 2330Palm Ridge Road, Sanibel Island.

Sandman Book Store—Saturday, Feb. 20. From 11 a.m. 16480 Burnt Store Road, Punta Gorda, Fl.

More dates to be announced soon

January 24, 2016

Hello Sweetheart…Get Me Val Sears

Hello, sweetheart. Yeah, get me rewrite will you? One of the giants has fallen, Val Sears, a newspaper legend out of a time of newspaper legends.

Whaddya mean you don’t know who Val Sears is. Val wrote features and covered politics in Ottawa, Washington, and London for the old Toronto Telegram and later for the Toronto Star. He wrote the great Canadian memoir about the Toronto newspaper wars of the 1950s, Hello Sweetheart…Get Me Rewrite.

Val was class, let me tell you; elegance and grace personified, both in print and in life. He was sort of the Scaramouche of newspapermen, blessed with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.

Yeah, hold on a minute, will you, sweetheart, while I brush away a tear. This is one of the tough ones. I loved the guy. When I grow up, I want to be a newspaperman like Val Sears. He was tall, laconic, with snowy hair pushed back from a smooth face, mouth turned at an angle as if he knew instinctively that whatever words came out of it were going to be laced with acid, and he was already savoring them.

Val moved slowly when he came into a newsroom or a bar or a cocktail party, taking in the world at his leisure. If he didn’t already know everyone in the joint, he soon would. Val was on the press plane when U.S. presidential candidate Ronald Reagan insisted a female reporter run her fingers through his hair to demonstrate that he didn’t dye it. Val still didn’t believe him, of course. Val never believed much of anything that a politician ever said.

The first time I met him, it was at a press reception then-Opposition leader Joe Clark threw in the garden of his Stornoway residence. I was in Ottawa doing a magazine piece on a controversial Progressive Conservative member of Parliament named Tom Cossitt. Cossitt is forgotten now, but at the time he had caused the Conservatives considerable embarrassment with his outbursts against bilingualism.

I wanted to talk to Clark about Cossitt. However, the people around their leader didn’t want anything to do with the story. They told me I could come to the reception but to stay away from Clark.

I was standing there wondering what to do when Val entered, lazily taking in his surroundings and then sauntering over. We introduced ourselves; he wondered what I was doing in town. I told him I was writing about Cossitt, but they wouldn’t let me talk to his boss.

“Joe?” Val said with that crooked, sardonic grin of his. “Hold on a minute.” He immediately went over to Clark spoke to him, nodded in my direction, and the next thing I knew I was talking to the Conservative leader, getting the quotes I needed for the story.

After that, Val and I became friends—or I liked to think of him as a friend. I was dazzled by him, his intelligence, his humor, the way he carried himself, the way nothing seemed to faze him, certainly not politicians, newspaper editors or women.

Okay, hold on, sweetheart. Maybe women could shake him up a bit. After all, he was human.

I always looked forward to our encounters, listening to that easy patrician drawl as it declaimed about the politics of the day in Ottawa, Washington, and in that particularly scabrous hotbed of gossip and rumor, the Star newsroom.

The homages to Val all pointed to the time in 1962 when Prime Minister John Diefenbaker called an election, and Val strolled into the press gallery—he never would have hurried—and announced, “To work, gentlemen, we have a government to bring down.”

But my favorite Val aphorism was “I’ve been around since the earth cooled.” Well, you got that right, sweetheart, I’ve now been around long enough to use the phrase myself, and I always think of Val when I do.

Yeah, I guess I am a little choked up. When I heard about Val’s death at the age of eighty-eight, I sat alone for a few minutes and let the tears flow. Yes, of course for Val, sweetheart, but also for the era that’s gone with him.

It’s probably mostly in my imagination at this point, but in those days newspapermen—a few women back then, but mostly men—were colorful, larger-than-life characters, livelier than most of the people they covered, world-weary, cynical, not taking guff from anyone. I was a kid then, freshly escaped from small town Ontario, newly arrived in this enthralling newspaper world, totally in awe of these guys.

Val, well, he loomed larger than any of his contemporaries. He was certainly more colorful, a little more world-weary and a lot more cynical and funny, with an added dash of sophistication thrown in for good measure. In his heyday, Cary Grant could have played Val. Or maybe it was Val who was playing a variation on Cary Grant. Hard to tell.

So that’s it, sweetheart, let’s dry the tears and put 30 on this. Whaddya mean you don’t know what “30” means? That’s the newspaper term for the end of the story. When you saw 30 back in the day, you knew it was over. Finished.

So you put “30” on Val’s life, will you? Hate to do it. Hate to think he’s not around anymore.

If I still drank, I’d lift a glass to Val Sears and the lost newspaper era in which he flowered. As it is, I think I’ll just sit here for a while and remember the guy who’d been around since the earth cooled. That earth is a little duller today.

Yeah, thanks, sweetheart. Tell you what? Why don’t we get together later at the press club for a drink? Listen, if my mother calls, don’t tell her I’m a newspaperman, okay?

She still thinks I’m a piano player in a whorehouse.

30

December 30, 2015

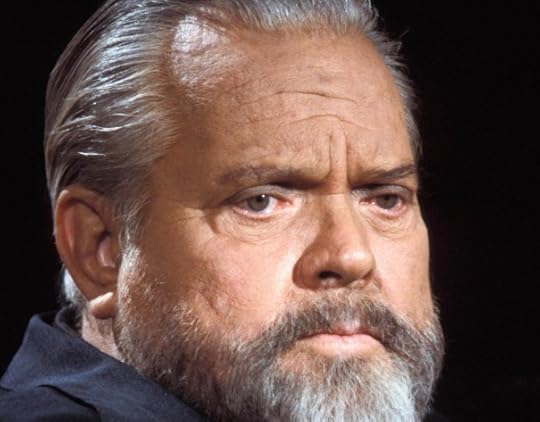

At Lunch With Orson Welles

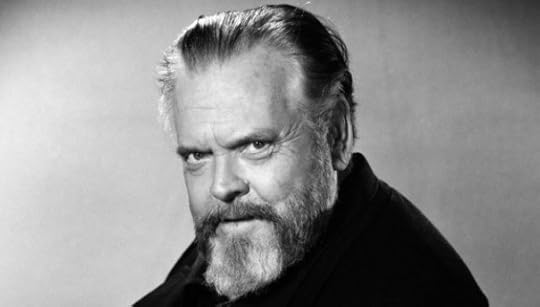

Unlike most of the people writing about him on the hundredth anniversary of his life, I actually met Orson Welles.

As I stood to shake his hand, I do remember thinking, Wow, here I am shaking the hand of the man who made Citizen Kane.

I had seen Welles a couple of times before, lunching on the patio at Ma Maison, sitting alone, a great, bearded Buddha in all his vast magnificence glaring out at the other patrons. At the time, Ma Maison on Melrose Avenue, was the hottest restaurant in Hollywood. Watching him, I thought, here was the genius who made what even then was generally regarded as the greatest American movie in the history of cinema, surrounded by the town’s most powerful movers and shakers. Yet he was not making Hollywood movies. Everyone was basically ignoring him. He certainly didn’t look happy, on display for all to see. Here I am, he seemed to say—what are you going to do about me?

CITIZEN KANE, Orson Welles, 1941, astride stacks of newspaper

This is the paradox of Orson Welles discussed endlessly over the course of his centenary year, the enigma of the boy wonder who could create Kane and then do—well, what did he do? Did he make more masterpieces or did he roam the world, illusive, unable or unwilling to repeat that early ground-breaking greatness? That’s the ongoing dispute, isn’t it?

It’s been played out constantly this year in new biographies, documentaries, as well as an exhaustive article in a recent issue of New Yorker magazine (The Shadow: A Hundred Years of Orson Welles).

There is even talk of another Orson Welles movie, The Other Side of the Wind, a feature he shot over many years with a cast that included directors John Huston (also long gone) and Peter Bogdanovich. Unlike so many Welles projects, this one was actually finished, but unedited and mired for decades in legal entanglements. It was supposed to have been released this year, but like so much about Welles, that promise was never fulfilled. Even in death, Orson somehow never quite shows up.

In the days when I wrote about movies, Welles fascinated me—how could anyone interested in film not be fascinated? I could never walk through the vaulted archways along Windward Avenue in Venice Beach without thinking that this is where Welles shot the famous opening border sequence for Touch of Evil, the last Hollywood studio picture he ever made (click HERE to view the opening sequence).

I drove into the hills of Malibu to interview John Houseman who had played such a pivotal role in Welles’s early career. Houseman hired him to direct a landmark all-black production of Macbeth for the Federal Theatre Project in the thirties, produced Welles’s controversial radio version of The War of the Worlds, and was also involved in the production of Citizen Kane, an involvement that had led to the dissolution of their partnership.

I drove into the hills of Malibu to interview John Houseman who had played such a pivotal role in Welles’s early career. Houseman hired him to direct a landmark all-black production of Macbeth for the Federal Theatre Project in the thirties, produced Welles’s controversial radio version of The War of the Worlds, and was also involved in the production of Citizen Kane, an involvement that had led to the dissolution of their partnership.

Two things I remember about my encounter with Houseman, who by that time had made The Paper Chase, won an Oscar for the role, and was best known to the world as an elderly, rather patrician character actor.

The living room of the hilltop house in which he and his wife lived was dominated by a huge indoor swimming pool. The furniture where we sat was arranged on the deck surrounding the pool. I’d never seen anything like it. The couple loved it, they said, and swam every morning in their living room-pool.

The other thing I remember is the otherwise affable and welcoming Houseman’s reluctance to talk about Welles. “That was all a long time ago,” he said, more or less closing down the subject. He had not seen his old friend and colleague for many years.

Charlton Heston with Janet Leigh in “Touch of Evil”.

Charlton Heston was much more willing to talk. I spoke to him a number of times, always proud that he had persuaded Universal Studios to hire Welles to not only appear in but also direct Touch of Evil.

I also spoke at length to Robert Wise who had directed a few classics of his own, including West Side Story and The Sound of Music. Wise was the middle-class, no-nonsense antithesis of the flamboyant Welles. He had started his career as a film editor and while at RKO worked on the editing of Citizen Kane and then, notoriously, it was Wise who was assigned to do reshoots and edit Welles’s next film, The Magnificent Ambersons, after Welles disappeared to South America in order to make a documentary.

This was a pivotal moment in Welles’s career, the beginning of the perceived self-destructiveness that was to haunt him for the rest of his life. Wise, sitting in his office on South Beverly Drive, still couldn’t believe Welles had so callously abandoned his own movie at a crucial stage.

He was defensive about taking over the production. “We did the best we could with what we had,” was the way he put it with a shrug. The result, while containing hints of greatness, is generally considered a mess and was a box office failure (Kane had not been a hit at the time, either), pretty much ending the freedom Welles had enjoyed working inside the studio system. (View the restored Ambersons opening HERE).

When I finally met Orson Welles, it was at Ma Maison. I was having lunch with a publicist named Michael Maslansky. “There’s Orson,” Maslansky said with a wave in the direction of where Welles was seated at his usual table.

A few minutes later, Welles abruptly appeared at our table, a great lumbering figure of truly enormous proportions. The only person I’ve ever met who could match Welles’s girth was the actor Raymond Burr.

I stumbled to my feet, flustered at meeting the Great Man. We shook hands, I mumbled something inane about how much I admired him. He nodded vaguely, and then brusquely turned to Maslansky who by now was also on his feet. Welles wondered if he could speak to him for a minute. The two of them walked a few feet away, engaged in a short, hushed conversation before Maslansky returned to our table and we finished lunch. We didn’t discuss what they talked about. The last I saw of him, Welles was back at his table, keeping a malevolent eye on the people who would no longer hire him.

At the end of all the arguments and speculation over Welles’s career and life, we are left with Citizen Kane. It remains, despite various attempts to knock it off its perch, everyone’s go-to choice as the greatest film ever made.

If it were not for Kane, it’s doubtful Welles would get the attention he has been receiving lately. His other films have their ardent defenders, but generally no one much remembers Magificent Ambersons or The Lady from Shanghai or The Stranger (his most commercial film), his Macbeth or Chimes at Midnight. Even the most famous of the Welles films that he didn’t direct, Carol Reed’s The Third Man, right up there when it comes to the greatest films ever made, is mostly forgotten.

Is Kane the greatest movie? Whatever your view, it remains a shimmering black and white feat of filmmaking, innovative, edgy, and cynical, refusing to give into the typical Hollywood happy ending of the time, and therefore timeless.

Recalling that brief encounter at Ma Maison, I think of the masterpiece Orson Welles made when he was only twenty-three. All the other debates about its creator fade away. Citizen Kane endures, and that is more than enough.

December 22, 2015

The Lost Comics

Even though they had already been hugely popular in North American newspapers for at least twenty years, King Features, the granddaddy of newspaper syndicates, is celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of a lost, all-but-forgotten art form: the comic strip.

Even though they had already been hugely popular in North American newspapers for at least twenty years, King Features, the granddaddy of newspaper syndicates, is celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of a lost, all-but-forgotten art form: the comic strip.

As far as anyone can figure, the first newspaper comic strip originated in 1895 from an artist named Richard Outcault. He created a strange, bald-headed little boy in a nightshirt and called him The Yellow Kid. The Kid spoke in balloons, hung around a squalid tenement area called Hogan’s Alley, surrounded by a recurring cast of characters.

By the time media baron William Randolph Hearst acquired The Yellow Kid as part of his newly-formed King Features, the strip was already hugely popular. Hearst had learned that one of the best ways to attract readers was to give them comic strips. As the century progressed, and big city newspapers became more and more competitive, their comics sections were powerful circulation boosters in ways unimaginable today.

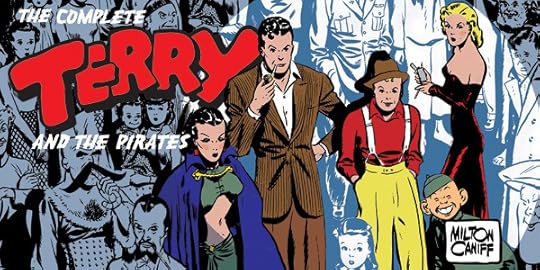

Large numbers of readers did not buy the paper for news, but for the comics, particularly with the introduction in the 1930s of the continuing adventure strip. In 1934 alone, such enduring comic characters as Flash Gordon, Jungle Jim, Li’l Abner, Mandrake the Magician, and Terry Lee of Terry and the Pirates came into existence.

Terry was drawn by a young cartoonist from Ohio by the name of Milton Caniff. Initially, a boy bouncing around what was then known as “the Orient”, Terry was aided by his journalist pal, Pat Ryan, outwitting a band of pirates led by the mysterious but very sexy Dragon Lady.

Terry was drawn by a young cartoonist from Ohio by the name of Milton Caniff. Initially, a boy bouncing around what was then known as “the Orient”, Terry was aided by his journalist pal, Pat Ryan, outwitting a band of pirates led by the mysterious but very sexy Dragon Lady.

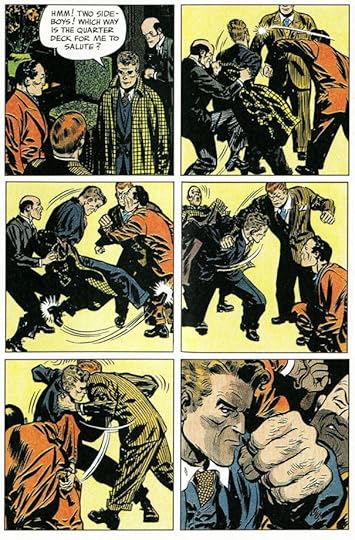

What brought the stories to life was Caniff’s superb draughtsmanship. He created beautifully-drawn panels, black and white through the week, blazing with color on Sundays, done in shadow and light and changing points of view reminiscent of the movies.

Through the thirties and forties, Terry became the most popular comic strip in America, his adventures followed daily by thirty-one million readers, his creator dubbed the Rembrandt of cartoons. In the 1940s, Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman were crudely-drawn comic book characters. The real talent in both illustration and story-telling was found in the comics section of your daily newspaper.

![Young_Caniff[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1450893435i/17481990.jpg) I grew into a teenager idolizing Caniff and the way he drew, wanting to become a newspaper cartoonist just like him. Back then, the daily newspaper strip was a way of escape. Movies could be visited at most once a week. Television was limited and closely watched over by parents afraid it would rot my brain.

I grew into a teenager idolizing Caniff and the way he drew, wanting to become a newspaper cartoonist just like him. Back then, the daily newspaper strip was a way of escape. Movies could be visited at most once a week. Television was limited and closely watched over by parents afraid it would rot my brain.

That left comics. They would rot brains, too, so I was restricted to one comic book a week. However, nobody ever objected to the weekend comics section of the newspaper.

By the time I discovered Caniff, he had abandoned Terry for a new character, Steve Canyon, an Air Force colonel, blond like Terry, but much more the two-fisted, womanizing (in a gentle sort of way) globe-trotting adventurer. It was not lost on my youthful eyes that Caniff, in addition to being able to summon far-off places filled with fascinating characters with a few strokes of an India-inked pen, also produced the most alluring heroines (and villainesses) in the comics. In those days, one took sexuality where one could find it, and, curiously enough, it often could be found inside the panels of Steve Canyon.

Caniff inspired me to become a cartoonist. I enrolled in the John Duncan Correspondence School of Comic Art. Duncan, a professional cartoonist who lived in Florida, sent me four thick binders full of instructions on how to draw. There were assignments to be completed and each week I would mail my drawings off to John Duncan who made corrections and sent them back. Each time I opened the corrected assignments, my heart sank as I realized I was not making a whole lot of progress as a cartoonist.

Nonetheless, I kept at it, obsessed, sitting hour after hour at the drawing board I had constructed, set up in my bedroom, in front of a window overlooking main street in Brockville, where we were living.

I even created my own Steve Canyon-like adventure comic strip. My hero was Garrett Champion. Gregory Peck in The Guns of Navarone, became the model for Champion. Like Canyon, my guy was a two-fisted adventurer, some sort of secret government agent as I recall, embroiled in various international intrigues that invariably involved my idea of a scantily-clad femme fatale.

By the time I gave up in frustration, I had drawn hundreds of panels on lengths of Bristol board. I’m not sure what happened to them. I suspect my father threw them away after I moved out. However, as an experiment, I sat down the other day and tried to recreate one of those Garrett Champion panels, discovering that I am no better today than I was all those years ago (the shaky results are on view above).

By necessity, Caniff spent his life sitting at a drawing board. This is made clear in Meanwhile… the fine, nearly one thousand-page biography of the artist written by Robert C. Harvey.

Adventure strips in their heyday ran seven days a week, three hundred and sixty-five days a year, no repeats, no summer hiatus. What’s more, Caniff had to do it so as to keep reminding readers of the plot and at the same time, keep the story churning forward complete with a daily cliffhanger. Then he had to rearrange the story for the full-page Sunday color installment so that readers who didn’t follow the story during the week, could also keep up with it.

In the early days of Terry and the Pirates, Caniff and his wife lived in a Manhattan apartment. They were, according to Meanwhile…, quite the sophisticated party people—except the party came to them. Late into many nights, their apartment filled with friends fresh from the theater or a movie, sitting around drinking cocktails, gossiping, while in a corner Caniff sat at his drawing board completing the day’s quota. Not until late in life was he able to visit any of the exotic locales he drew.

Caniff’s remarkable artistry and story-telling feats finally have been preserved in a series of beautifully-produced books from the Library of American Comics. Flipping through these volumes, my heart aches that they weren’t available when I was a kid. If I’d had them back then, I would have thought I’d died and gone to comic heaven. As it is now, a much older man can only flip through their pages in head-shaking admiration at what Caniff was able to accomplish.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but even if I had been any good at cartooning, I had arrived too late at the party. As I daily devoured Steve Canyon, that sort of continuing adventure strip was dying, killed off by television and the movies.

Even though Steve Canyon’s readership had dwindled to almost nothing, King Features did not have the heart to fire Caniff. He died in 1988, still at his drawing board. As soon as he was gone, so was Steve Canyon. Even though Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon are mostly forgotten today, Caniff’s influence remains strong. Those crudely drawn superheroes of the 1940s have become pop culture icons, rendered in comic books and graphic novels with the sort of artistry, cinematic movement, and attention to detail that almost certainly is inspired by Caniff.![Caniff-SCanyon_hc1954[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1450893435i/17481993.jpg)

Also, it’s hard to imagine that Terry and the Pirates didn’t provide at least some inspiration for George Lucas and Steven Spielberg when they created the Indiana Jones adventures.

As for that frustrated teenage cartoonist in Brockville, thankfully, he discovered he was somewhat better at writing stories than he was drawing them. But all these years later, still a glutton for artistic punishment, he finds himself back at the drawing board, trying to get Garrett Champion right.

And, of course, failing.

December 1, 2015

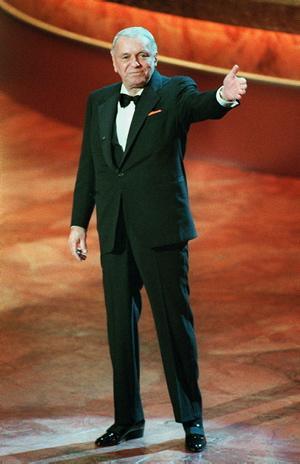

Blowing Out the Candles at Frank Sinatra’s Birthday Party

Frank Sinatra will not attend his hundredth birthday this month. However, Frank was at his eightieth birthday party. I know because I was there with him. You might say I helped him blow out the candles.

Mind you, we weren’t alone. The Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles was filled with hundreds of well-wishers. An eclectic gathering. You could turn around and nearly bump into Louis Jourdan, the star of Gigi, still looking great all these years later. Were Frank and Louis friends? Who knew?

Not far away, Gregory Peck, a longtime Sinatra pal, huddled with Anthony Quinn, and you couldn’t help but think, Wow, the two stars of The Guns of Navarone together again.

A petite young woman sheathed in white, looking absolutely spectacular, floated past. This turned out to be the then-unknown Selma Hayek. Was Selma a friend? Was I?

Well, no, not really, and probably not Selma, either. I had encountered Sinatra once before in 1975 when he returned to the concert stage after a brief retirement. Ol’ Blue eyes was back and appearing at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. Harold Ballard, who owned the Gardens (and the Toronto Maple Leafs), had gone to a great deal of effort and expense to attract Sinatra and there was excitement of the kind ordinarily reserved for visiting royalty and heads of state.

I thought of Sinatra as not much more than a talented thug, what with his organized crime connections, his disdain for the press, and his increasingly throwaway movies (Dirty Dingus Magee, anyone?). In the youth-obsessed, disco world of 1975, Frank Sinatra seemed an anachronism, the boozy, chain smoking, broad-chasing personification of Las Vegas cheesy.

With that kind of attitude, of course I was assigned by Toronto’s Sunday Sun newspaper to do a piece in advance of his visit. I phoned around the country, talking to anyone I could think of who might be able to provide insight into the Sinatra legend.

I interviewed everyone from Hank Greenspun, the editor and publisher of the Las Vegas Sun, who knew Sinatra personally, to Nat Hentoff, the respected arts critic of the Village Voice, who had written about him extensively. Somewhat to my surprise, everyone I talked to had mostly good things to say about him. Greenspun said he had never seen his friend’s dark side. Everyone talked about how generous and caring he was. Good ol’ blue eyes.

By the time I finished the article, I was intrigued enough that when my wife at the time, Lynda, managed to get her hands on concert tickets, I reluctantly went along, expecting to see an aging crooner, just out of retirement, voice fading, leaning hard on past glories.

But from the moment he stepped on the circular stage running through the Gardens he cast a spell and created an excitement that even a skeptic like myself couldn’t resist. It helped that we sat close enough that I could have reached out and touched him.

Dressed in trademark black tie, backed by a full Nelson Riddle orchestra, he transported us all back to a mythical world shimmering in black and white, where beautiful women in evening gowns sipped martinis in smart night clubs, and the music swept you away.

When he sang Harold Arlen’s “One For My Baby (and One More for the Road)”, the highlight of the evening, I was choking back tears. My wife and I, along with everyone else, floated out of the Gardens when it was over. It was one of the most romantic evenings I have ever spent, and I spent it with Frank Sinatra.

Nearly two decades later, November 19, 1995, at the Shrine, the night celebrating Sinatra’s birthday was more head-scratching than it was romantic. At the beginning, Sinatra was trotted out, once again in black tie, looking pretty darned good, it seemed to me, considering his age and the fact that he had spent most of his years drinking Scotch, smoking cigarettes, and staying up to the wee small hours chasing dames.

He was introduced by Bruce Springsteen, the first in a series of unlikely musical guests. Sinatra smiled, waved, more or less acknowledged the standing ovation, and then Springsteen escorted him over to a small table with a red table cloth to the left of the stage where he was seated with his wife, Barbara. That was the last we heard from him.

He was introduced by Bruce Springsteen, the first in a series of unlikely musical guests. Sinatra smiled, waved, more or less acknowledged the standing ovation, and then Springsteen escorted him over to a small table with a red table cloth to the left of the stage where he was seated with his wife, Barbara. That was the last we heard from him.

Springsteen was a fellow Jersey boy, so that more or less explained his presence. Bob Dylan, who followed, was an admirer. Patti LaBelle, Hooti and the Blowfish, Tony Danza were more problematic, as was Little Richard, who, if anything, represented the rock n’ roll Sinatra detested and that at one time nearly put him out of business. There was no sign of Dean Martin, Sammy Davis (who had died five years before), Shirley MacLaine or any of his pals from the Rat Pack era.

The only performers you could readily associate with Sinatra’s past were Vic Damone, Steve Lawrence, and Eydie Gormé. Tony Bennett, who Sinatra once said was the singer he most admired, was there, too.

It was hard to imagine what Sinatra thought of all this. Those of us in the theater spent the evening staring at the back of his head. The subsequent television broadcast cut occasionally to him smiling—or not—generally looking slightly distracted. After all, he had spent a lifetime being feted and celebrated, this night with people he barely knew, wasn’t going to shake him up too much.

At the end, everyone gathered on stage to sing, not “My Way,” which might have been expected, but “New York, New York,” forgetting for a moment we were all in Los Angeles. Sinatra was brought onstage for the finale, and he actually sang into a microphone, although you could barely hear him.

Afterward, at the backstage after-celebration celebration, the Birthday Boy was a no-show. Springsteen sat for a time with his wife Patti Scialfa. Mike Myers chatted with Martin Short while I wondered yet again at the strange mix of celebrity the night had attracted. Out back, the TV crew who had worked on the broadcast wasn’t looking at what they had taped. They were mesmerized by a special about lost Beatle songs that recently had been released.

That night pretty much marked the last time Sinatra appeared in public. Less than three years later, suffering from various illnesses, including dementia, he died of a heart attack.

The years since have been kind to him. Freed from the constant stories about his mob connections, his women, his temper, the whole Rat Pack thing having lost its louche trappings and taken on a kind of hip nostalgia, we have Sinatra singing, the way he was that long ago romantic night at Maple Leaf Gardens, the way he wasn’t at the Shrine auditorium when everyone showed up for his eightieth birthday.

I was there, too. Good ol’ Frank. My pal. Did I mention I helped blow out the candles?

November 17, 2015

The New Tree Callister Mystery Is Now Available on Amazon

The Four Wives of the Sanibel Sunset Detective has just become available on Amazon. You can download an ebook copy immediately or pre-order the print version and have it on your doorstep when it is published November 21.

The Four Wives of the Sanibel Sunset Detective has just become available on Amazon. You can download an ebook copy immediately or pre-order the print version and have it on your doorstep when it is published November 21.

For your copy of the new book, simply click HERE.

I think The Four Wives is the most intriguing Tree Callister novel yet–certainly it is the most complicated since it involves matters of the heart.

Tree, happily married on his fourth try, must nonetheless confront his past when his three ex-wives show up on Sanibel Island. All three wives are in some kind of trouble. Tree must try to get them out of the hot water his exes find themselves in, free his best friend from prison, outwit a Russian oligarch who doesn’t like him, solve a murder or two…

And, oh yes, deal with Marilyn Monroe who shows up with marital advice.

It’s another page-turning fun read in the Sanibel Sunset Detective series of mystery novels.

Order your copy now. I think you’ll enjoy it!

Get your copy of The Four Wives of the Sanibel Sunset Detective HERE.

October 22, 2015

Justin Trudeau’s Dad and Me

In Donald Brittain’s powerful 1978 television documentary The Champions, about the lifelong battle for Canada’s destiny between Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque, there is a shot of Trudeau being interviewed in the midst of the 1968 Liberal leadership convention.

Days away from becoming prime minister, Trudeau is seated in a glass-walled TV studio in the midst of the convention. The camera pans around delegates and members of the media pressed against the glass for a look at this emerging phenomenon.

The panning camera comes to a stop and briefly focuses on a skinny kid in a trench coat fumbling with a camera.

That skinny kid is me, in grainy black and white, trying to take Pierre Trudeau’s picture. I must say, I am no better with a camera today than I was way back then.

To my amazement, I found Brittain’s documentary online (at the National Film Board’s web site). I sat watching it on my computer screen, fascinated all over again, not only by my (very) brief appearance but overwhelmed by the realization I have now lived long enough to witness not only the ascension of Pierre Elliott Trudeau into Canadian life, but now his son, Justin.

To view scenes from that convention all these years later as Justin Trudeau becomes prime minister of Canada is to be reminded how much we have changed in this country.

Today, as Pierre’s son takes power, I’ve become an old man, contemplating the end of things, not their beginnings. Back then I was just starting out, everything in front of me, a not-very-enthusiastic student at Ottawa’s Algonquin College journalism school. Somehow, our teacher, a quiet, patient man named Merv Kelly, had scored accreditation so our class could attend the Liberal convention.

I can’t imagine the press today having the kind of unfettered access we had that weekend at the Ottawa Civic Center. It seems to me we could wander just about anywhere, and rub shoulders with all the candidates, although, in truth, the only one that interested me was Trudeau. I trailed him around everywhere.

Friday night we all crowded into the lobby of Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier Hotel to hear the folk duo of Ian and Sylvia–very popular at the time–performing live. Suddenly, there was a stirring at the back of the lobby, followed by a wave of excitement as Trudeau appeared unexpectedly and was hoisted through the cheering crowd. If there was security, it wasn’t evident. There seemed to be only Trudeau up on a makeshift podium with Ian and Sylvia, making an impromptu speech, the crowd going crazy.

Friday night we all crowded into the lobby of Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier Hotel to hear the folk duo of Ian and Sylvia–very popular at the time–performing live. Suddenly, there was a stirring at the back of the lobby, followed by a wave of excitement as Trudeau appeared unexpectedly and was hoisted through the cheering crowd. If there was security, it wasn’t evident. There seemed to be only Trudeau up on a makeshift podium with Ian and Sylvia, making an impromptu speech, the crowd going crazy.

None of the other leadership candidates caused anything approaching this kind of excitement. They all seemed old and worn out. Trudeau, on the other hand, not unlike his son nearly five decades later, was new and exciting. No one had seen anything quite like him; he was a breath of fresh air in what was then such a staid and conservative country.

Anyone who looks back on those times and remembers the good old days probably didn’t have to live through them. It was a mostly all-white society, in many ways still under the colonial shadow of Britain (Canada had achieved its own flag amid much rancor only a couple of years before). The white men who ran the country closed everything up tight on Sundays. You could not even go to a movie.There were still separate tavern entrances for men and women.

If you wanted to buy booze, you went to the government-operated liquor store, filled out a form, signed your name, and then took it to the counter and handed it to a clerk who then disappeared behind a partition to reemerge minutes later with your purchase in hand–in a plain paper bag, so no one would know you were a shiftless drunkard.

Everything was overcooked and bland. There were only a few decent restaurants and eating out was still considered a special event. In retrospect, Trudeau’s major achievement other than repatriating the constitution from Britain, may have been opening the flood gates to immigration, thereby making it possible to get a good meal in this country.

Books such as Peyton Place, James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer were banned outright in many quarters. In Toronto, people went to jail, literally, for displaying art that was considered pornographic.

The first time I encountered Trudeau, I was still in high school. Our Brockville Collegiate Institute class came to Ottawa to tour the Parliament buildings–you could just walk into the place back then.

We were supposed to meet with John Matheson, our very popular Liberal member of parliament (probably the last time Brockville ever elected a Liberal). However, Matheson, whom I admired tremendously, was ill that day. He did speak to us over the phone, though, and said he was sending a close friend to substitute for him.

In walked Pierre Trudeau, who was, at the time, Minister of Justice. What did I think of him that day? Was I mesmerized by the man who was soon to lead the country? Not at all. I thought he was boring.

But not at the convention a couple of years later. By then, Trudeau was electrifying the country. Those of us who were part of that time never quite lost our affection for him or forgot the sense of excitement he brought to dull Canadian life. As most Canadian politicians do, he over stayed his welcome, and, as has been the case with President Obama in the U.S., the reality of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau never quite lived up to the promise of the sports car-driving, movie star-dating young maverick (not so young after all; it turned out Trudeau was forty-eight when he was elected leader of the party).

I won’t be so melodramatic as to say that weekend at the Liberal convention changed my life. But certainly much changed that year. A couple of months later, school behind me, I was a reporter working for a daily newspaper, The Oshawa Times, while Pierre Trudeau crisscrossed the country in his first election campaign as prime minister, mauled by huge crowds everywhere he went. Trudeaumania was in full flower.

My first day at work I was preparing to cross the street to the Times when I glanced around and saw a lanky, bald-headed man standing on the corner. I realized with a start that this was Robert Stanfield, the leader of what was then called the Progressive Conservative Party, the guy running against Trudeau to be prime minister. I couldn’t believe it. He was all alone, not a soul around him. I went over and shook his hand, understanding at that moment Stanfield didn’t stand a chance in the election. And, of course, he didn’t.

Much has happened since Pierre Trudeau stepped into Canadian life, both to me and to the country. Now, as Justin Trudeau becomes Canada’s second-youngest prime minister, I suppose there is a certain closing of the circle.

I wonder if Justin would like his picture taken.

![old-typewriter[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1453808427i/17873947._SX540_.jpg)

![1099fecc080df5d1bb0879cb9026e7fd[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1450893435i/17481991._SY540_.jpg)