Ron Base's Blog, page 11

October 20, 2015

First Look: Ron Base’s new novel, “The Four Wives of the Sanibel Sunset Detective”

Tree Callister and his old friend Rex Baxter were having lunch on the screened-in terrace at the Lighthouse Restaurant, just off Sanibel Island, when Rex said, “I’m getting married in the morning.”

“The song from My Fair Lady by Lerner and Loewe,” Tree said.

“The song from My Fair Lady by Lerner and Loewe,” Tree said.

“No,” Rex said. “I’m getting married in the morning.”

“I would argue My Fair Lady is the best musical of all time,” Tree said. “The blend of story and song in exactly the right measure, the ability of Lerner and Lowe to conjure a Shavian sensibility that echoes the original play without being slavish to it. The inspired, witty score, each song a singular achievement in that once you hear it, you can’t stop humming the tune.”

Rex looked irritated. “Have you gone completely nuts? Don’t answer that. This has nothing to do with Lerner and Loewe. I, Rex Baxter, plan to marry tomorrow morning.”

Tree looked at him in amazement. “You’re getting married?”

“Tomorrow morning,” Rex repeated.

“Who are you marrying?”

“Who do you think?”

“My ex-wife?”

“You see?” Rex said. “People underestimate you. Given the opportunity, exercising a little patience, you can figure these things out for yourself.”

“You’re marrying Kelly. Kelly Fleming.”

“You seem to be having trouble with the concept,” Rex said.

“You have talked to Kelly about this?”

“I may have passed the idea by her, yes.”

“I see,” Tree said.

“I’d like you to be my best man,” Rex said.

Most of the luncheon diners on the terrace had departed. The marina beyond the restaurant sweltered in the afternoon sun, the lines of yachts, glistening white, unmoving, hardly a stir in the air.

Finally, Tree cleared his throat and eased himself forward, leaning his elbows on the table. “I’m going to be the best man for my best friend who is marrying my ex-wife.”

“Do you have a problem with that?” Rex asked.

Tree thought about it for a moment. “No,” he said. “I don’t suppose I do.”

Rex and Tree had been friends, as Rex liked to say, “Ever since the earth cooled,” or at least going back to Chicago when Tree was a newspaperman and Rex, a former actor in mostly B pictures, hosted an afternoon movie show on WBBM-TV. This was before Rex became the station’s weatherman, beloved of all the Chicagoans who ever wanted to know when the next snowstorm would batter the city. By the time Tree, and his wife, Freddie, moved to Sanibel-Captiva, Rex was already embedded in the community, the president of the Chamber of Commerce, once again beloved, and therefore in his element.

It was Rex who had found an office for Tree at the Chamber of Commerce Visitors Center so that Tree could set up The Sanibel Sunset Detective Agency, a move Rex had lived to regret, Tree’s misadventures as a private eye on Sanibel Island having caused him untold amounts of grief, and had, according to Rex, interfered with the thriving tourist trade.

Now Tree supposedly had retired, tired, he said, of the constant jeopardy he found himself in on an island where nothing ever happened—except to him. Rex, meantime, had met and fallen in love with a former Chicago newscaster, Kelly Fleming, who, as it happened, was once married to Tree—the second of Tree’s four wives.

In fact, Rex had originally introduced Kelly and Tree.

Life certainly could be complicated, Tree mused. Well, he was open-minded about these things, wasn’t he? As long as his friend was happy, that’s all that counted. Wasn’t it?

“This is all happening pretty fast,” was all Tree could think to say.

“Not that fast,” Rex countered. “I’ve actually known Kelly longer than you.”

“That’s true,” Tree had to admit.

“Besides, I wanted to get her before she changes her mind.”

Rex was kidding, Tree thought. Wasn’t he?

A heavyset woman appeared at their table. She focused on Rex. This was not unusual. Rex had been a star television weatherman throughout Heartland America. Sanibel attracted tourists of a certain age from that Heartland, all of whom seemed to recognize their old TV pal.

The woman said in a gentle, breathy voice that Tree immediately recognized, “Rex? Rex Baxter. Is that you?”

Rex gaped in surprise before he said, “Judy? Judy Blair?”

“It’s me, Rex,” she said with a big smile.

He lumbered to his feet in time for Judy to embrace him. “I thought it was you,” she said. “I can’t believe it. What are you doing here?”

“Well, for one thing,” Rex said, “I’m having lunch with someone you might remember.”

She turned and for the first time took a good look at Tree. Her eyes widened. “Tree!”

Now it was Tree’s turn to rise awkwardly. Only Judy didn’t embrace him. Various emotions played on her smooth, round face—a face Tree barely recognized after all this time. Rex said to Judy, “You don’t recognize the guy you married? The father of your children?”

“Yes, of course,” Judy said, the warmth in her voice cooling. She mustered a smile. “It’s been a long time, Tree.”

“Yes,” Tree said.

A man appeared behind Judy. Tree had a quick impression of a large, extremely solid fellow with a bull neck, a dramatically-lined face topped by bristling hair he immediately identified as dyed—the male of the species, no matter how prosperous, seemingly incapable of hair coloring that looked at all natural.

Judy turned nervously and said, “Alexei, there you are.”

“Yes, I am right here,” her companion said. “Would you like to introduce me?”

“My husband, Alexei Markov,” Judy said. “Alexei, these are friends from Chicago. Rex Baxter and Tree Callister.”

“Good to meet you,” Rex said, sticking out his hand.

An attempt had been made to hide the bulk of Alexei Markov beneath a radiant Tommy Bahamas shirt, not tucked in at the waist. The attempt had failed. When he smiled, the dramatic lines of his face softened somewhat and you were given the impression that behind that rock-hard countenance there lurked the charm that would have attracted Judy. He took Rex’s hand in his.

“A pleasure,” he said. Then he turned to Tree, and the soft smile was wiped away. “I think you are less a friend, more the ex-husband, am I correct about that?”

“I’m afraid so,” Tree said. He was holding out his hand.

Alexei Markov looked at the proffered hand but did not take it. “I have heard so much about you,” he said. “None of it very good.”

“Alexei, that’s enough,” Judy said in a stricken voice.

Tree took his hand away and looked at Judy. “It’s good to see you, Judy.”

Judy gave another nervous smile. “Yes, certainly a surprise.”

“How long are you here for?” Rex asked.

“We have bought a house here,” Alexei Markov said. “We plan to spend much time in this beautiful place.”

“I’m the president of the Chamber of Commerce on Sanibel and Captiva,” Rex said. “If there’s anything I can do to help you settle in, please let me know.”

Rex handed Judy one of the business cards he seemed able to produce with a magician’s sleight of hand. She took the card and gave a fleeting smile. “That’s very kind of you, Rex. You always were so kind.”

Tree noticed he was not included in Judy’s kindness category.

Markov, demonstrating an equal ability at sleight of hand, plucked the card out of his wife’s fingers. “Yes,” he agreed. “That is kind of you, Mr. Baxter. We are most appreciative.” He looked at his wife. “Judy, I believe he had better have some lunch.”

“Good to see you,” Judy said to no one in particular.

Markov shot Tree one final, speculative look before taking his wife by the arm and leading her away. Rex watched them disappear into the dining room. “This confirms my suspicion that if you live long enough on this island, you will eventually meet everyone you ever knew from your past life.”

“Hard to disagree with you,” Tree said.

“Judy didn’t seem very happy to see you,” Rex said.

“I can’t blame her,” Tree said. “I wasn’t much of a husband.”

“You’ve improved,” Rex said. “What’s more, it only took you three marriages to do it.”

“I’m a slow learner,” Tree said.

“That’s certainly true,” Rex said, getting to his feet. “Just make sure you’re at the Island Inn tomorrow morning at eleven.”

“You’re getting married at the Island Inn?”

“I’ll be the guy on the beach with a big smile on his face,” Rex said.

“I’m happy for you, Rex,” Tree said. “You know that, don’t you?”

Rex gave his old friend a skeptical look.

And then he winked.

The Four Wives of the Sanibel Sunset Detective will be published in November by West-End Books.

September 9, 2015

A Month In Provence: What? I’m Not In Provence?

The black bulls are charging outside our apartment in Uzès.

We are in this medieval French town to spend the next month experiencing the joys of Provence. Who knew about bulls?

Les tauraux are part of the tradition and commerce in the region, and we have arrived for the Fete Votive, an annual celebration highlighted by the running of the bulls along the Boulevard Gambetta, the town’s main drag—an unexpected start to our time in Provence.

Except, monsieur, désolé, but you are not in Provence.

Huh?

As usual, my geography in these matters is shaky, although in fairness, pinpointing what part of France we are in depends on who you talk to. Peter Mayle, author of A year in Provence, a local resident and something of an expert in these matters, while acknowledging the confusion over what exactly constitutes Provence, pronounces that anything east of Avignon is Provence. Anything west is not.

Uzès is, ahem, slightly west.

For the purposes of tourism, and with a bow to a certain amount of snobbism, there is an inclination to attach the town to Provence, my lame (and snobby) excuse for thinking that’s where we were headed. Accuracy and the French government places it in the department of the Gard, in the region of Languedoc-Roussillon in the arrondissement of Nîmes.

Never mind. Wherever you choose to locate it, Uzès occupies its own unique space, a sort of timeless French Brigadoon rising out of the misty countryside, surrounded by vineyards and fields of lavender, graced by plane trees, overseen by The Duchy, not quite a fairy tale castle—too many rough and tumble architectural influences for Disney-type fantasy—but a looming reminder that this is an ancient town of old stones, medieval stones built upon Roman stones caped by Renaissance stones.

Someone has lived here since the dawn of civilization. The Romans put it on the map, constructing an aqueduct from a spring in Uzès that ran fifty kilometers to the town of Nîmes where the first century inhabitants enjoyed running water and flush toilets.

That ended after five hundred years with the arrival of the Visigoths who did not wash, thus entering an unfortunate era where nobody much bathed, which led to the invention of French perfume. But perhaps we are getting ahead of ourselves.

The remnants of what used to be called Gaul are very much in evidence throughout the region, from the Roman ruins in Lyon to the well-preserved amphitheater in Nîmes (where they still hold bullfights twice a year)to the region’s piece de resistance, the Pont du Gard, not far from Uzès, built to bring water across the Gardon River, and still very much as it was in Roman times—except now you can kayak on the river beneath the bridge’s arches, something that presumably the Romans never did.

Our large, airy apartment overlooks the Place aux Herbes, known for its Saturday morning market, bursting out of the square, crowding both sides of the Boulevard Gambetta. In August, the market attracts almost as many visitors as the bulls. You can hardly move for people clamoring for figs, and melon de Cavaillon, strawberries, locally produced sausage, olive oil, chickens with their heads still attached (so you know they are fresh?), lotte, durade (or sea bream), tuna the size of a small shark, pâtés, men’s and women’s clothing, local art.

Not everything you can imagine, but close, all of it erected in a clamor beginning at five in the morning, disturbing the starlings in the plane trees, waking the weary outsiders in the apartment above the square, ready by nine o’clock and then stripped down again at one.

The merchants around the Place aux Herbes are delighted with the influx of tourists. Business has never been better they say what with all the French families here for the traditional August holiday. In the cafes surrounding the square and on Boulevard Gambetta you can barely find an empty seat. If you do, you are soon reminded of an abiding fact of French life in the twenty-first century: everybody still smokes.

It remains an astonishing phenomenon coming from the comparatively smoke-free environs of North America. Here mothers stroll along pushing a carriage or pulling a child with one hand, casually and unselfconsciously puffing on a cigarette with the other hand. Cigarette butts are everywhere, clogging the cobblestones.

In Paris, the problem of cigarette butts is so great—three hundred and fifty thousand tons collected each year—that you can be fined for dropping one on the street. That doesn’t appear to have changed anything. The streets are littered not with dog merde but discarded cigarettes.

There is no escaping the smokers, but you can drive out of Uzès to investigate the neighboring towns, each featuring a singular attraction.

Nearby, San Quentin la Poterie is known, as its name suggests, for pottery. Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, picturesque under a blazing sun on the Sorgue River, boasts antiques markets. The hilltop redoubt that is Ménerbes is the scene of author Peter Mayle’s bestselling A Year in Provence, although he no longer lives in the farm house outside of town featured in the book.

Avignon provides ancient fortress walls, Le Palais du Papes, or the Papal Palace, the seat of Western Christianity during the fourteenth century, and the iconic le Pont d’Avignon, the bridge across the Rhône River that doesn’t quite reach across the Rhône, but never mind, everyone comes to stand on it, anyway.

Avignon provides ancient fortress walls, Le Palais du Papes, or the Papal Palace, the seat of Western Christianity during the fourteenth century, and the iconic le Pont d’Avignon, the bridge across the Rhône River that doesn’t quite reach across the Rhône, but never mind, everyone comes to stand on it, anyway.

An hour or so away, the seaside town of Le Grau-du-Roi offers—exactly what it offers eludes this visitor, save for sea views, a wide plage, and impressive sand castles whose artists accept a Euro or two in payment for your admiring looks.

Anduze sits not far from the Grotte du Trabuc, twelve kilometers of vertigo-inducing underground caverns that only Nature’s wildest imagination could create. Anduze itself turns out to be an unpretentious gem with a restaurant, Le Cévenal, offering more luncheon escargots that this lover of snails has ever seen.

You can quickly become caught up in the dreamy, sun-drenched rhythms of life in the Gard: the walks through cobbled streets, the daily ritual of the baguette, the Comté cheese, the duck liver mousse (definitely the duck liver mousse), the morning smell of freshly baked croissants escaping from the local patisserie, not to mention—God help you—the cheap allure of accordion music drifting up through open windows into your apartment from the Place aux Herbes. All the clichés of living in the south of France that you swear are not going to seduce you, seduce you.

This is the fantasy of a life in France, of course, the unreal made real for a time. Not so far away thousands of desperate refugees fight and die to escape Middle East wars while European governments procrastinate and debate. In Paris, the government wrestles with what to do about a growing and restive ethnic population, not far removed from the horrors of the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

None of this penetrates the timeless stones of Uzès. Brigadoon dreams on through the summer heat, making it far too easy to ignore reality.

Soon enough, though, August is swallowed into cooler September and the crowds abruptly are absent from Place aux Herbes and the Boulevard Gambetta. Everything quiets. It is nearly time to return to a place where no bulls run on the street, where they do not bake the baguettes daily, and where, sadly, you can once again understand what people are saying, and where, most of the time, you don’t need your wife to translate.

There is a final romantic dinner in the garden at Le Bec a Vin, a last moonlit stroll through the old town, shadows dancing off the stone walls, those old, old stones, a saddened sense that you are leaving…where?

Well, you are not leaving Provence. Or are you?

August 26, 2015

The Cutting of the Olive: Lessons in Life and Cooking From the South of France

I have learned how to cut an olive in half.

I now know that in order to make pissaladière, a traditional and very popular French pizza-type dish, one sweats the onions, one does not brown them.

Adding olive oil to bread dough makes kneading much easier.

I have also learned that Spanish olive oil has more guts than French olive oil, but don’t tell anyone, particularly the French.

There is an art to cutting anchovies in half with scissors that I was not able to master.

Do not buy spices already ground. Buy them whole and then grind them to bring out the true flavor. But do not use anything other than a mortar and pestle made of lava stone.

These and other life and culinary lessons are gleaned from Madame Petra of the Pistou Cookery School in Uzès, France. Madame Petra is Petra Carter, a lively Irish woman, who has so far jammed several lifetimes into a single life.

Born in Indonesia, raised in Dublin, she speaks six languages, has managed tented safari camps in Kenya and Tanzania, has written restaurant reviews for the Irish Times, edited the food pages of the Irish Tatler, published her own food magazine, and now gives cooking classes in a kitchen hewn out of 16th century stones sitting upon Roman ruins.

Born in Indonesia, raised in Dublin, she speaks six languages, has managed tented safari camps in Kenya and Tanzania, has written restaurant reviews for the Irish Times, edited the food pages of the Irish Tatler, published her own food magazine, and now gives cooking classes in a kitchen hewn out of 16th century stones sitting upon Roman ruins.

There are readers of this blog who may raise eyebrows in surprise, unaware that the author’s interest in food extends much beyond the eating of it. Those eyebrow-raising skeptics might be onto something.

However, the author’s wife Kathy is a combination of passionate foodie and avid Francophile, and just about anything she wants to do turns out to be a lot of fun. Thus we have cooked with a chef in Barcelona, and attended the Ritz Escoffier School in the kitchens of the Hotel Ritz in Paris where I am a graduate, and where my tarte au abricot inspired such envy from my wife that she knocked it onto the floor. She claimed it was an accident. Ha!

In addition to allowing me to swagger around announcing to the disbelieving that I cooked at the Ritz and have a diploma to prove it, these classes are a great way to better know the place where you are eating. They provide a closer view of how the locals live, and invariably one meets unusually lively and entertaining people from all over the world.

Even better, after throwing myself on the mercy of the chef (“I promise you, I am the worst student you will ever have”), I usually don’t have to do much more than look interested, and enjoy a wonderful meal.

There are six of us present for Madame Petra’s class: Suzanne and Grant, a young couple from Sydney, Australia who have just married and are on their honeymoon; Traudl, from Salzburg, Austria; Kerstin from Germany who has lived in France for over thirty years; a couple of Canadians spending the month in Uzès.

As is usually the case, most of those present have more than a passing interest in food and its preparation. There is ordinarily only one outlier in the group.

Me.

“I will be the worst student you ever have,” I tell Madame Petra, repeating my usual mantra at the start of a cooking class. Madame Petra’s ready smile slips only briefly.

She then takes us through a basic course in preparing what she calls the little dishes of Provence. There will be nine in all, including the aforementioned pissaladière, where my ability to cut an olive in half came into play and which, I suspect, made me the envy of the class.

However, the dish also requires the cutting vertically in half of anchovies, a task I took one look at, panicked, and turned over to Kathy, who not only accomplished this with alacrity but also laid out the thinly cut anchovies in an attractive latticework pattern atop the pastry of the pissaladière.

I then swept in and added the half-cut olives, accompanied by gasps of admiration from my classmates.

Goat cheese was marinated in olive oil. Salted duck breast, a French delicacy that requires a lot of gros sel or sea salt and then must sit for two weeks (patience is required to be a Provençal cook, I learned).

Other dishes: moules pesquieres, a dressing made with sweet onion, green peppers, tomatoes, balsamic vinegar and fruity olive oil (Spanish, of course) that brings the taste of mussels to dramatic life; faisselle or fresh cheese, also traditionally French, served as a savory dish made with fresh herbs and crushed spices; and prawns flambéed in pastis.

Best of all were the figs. They are cut into quarters almost to their base, then pressed at the sides until they open up to allow for the insertion of a piece of goat cheese before being wrapped in thinly sliced dry-cured ham, drizzled with a lavender honey balsamic glaze, and warmed in the oven. Superb!

The price that must be paid for all this food preparation is, of course, the eating of it. When we finally sit down to lunch, Madame Petra, who also teaches a course in the stuff, brings out generous amounts of local red and white wine. Her smile loses a bit of its elasticity when she discovers that not only am I her worst student, but I also don’t drink alcohol, the sort of revelation that can get you run out of town in these parts.

Fortunately, there is no shortage of wine drinkers. The meal is, as we all suspected it would be, outstanding. But the best part—and this is true of any of the cooking courses I have encountered—is the delightful company. Everyone talks up a storm.

When it comes to lively and entertaining, Madame Petra certainly fills the bill. The story of how she met her current boyfriend is worth the price of admission: he was the one bachelor among twelve hanging out in the town square at Narbonne who had good teeth. She arranged a lunch, and invited these village bachelors. The only bachelor who didn’t attend was the guy she actually wanted to meet—the one with the good teeth. Undaunted, Petra made sure he came by later; they have been more or less together ever since.

By the time we finish the meal, accompanied by a desert of fresh peaches swimming in local muscat wine, and have gotten to know one another, it is nearing four o’clock in the afternoon.

In the glow of the end of a wonderful day with a charming, talented chef, everyone agrees that the highlight was the way in which the olives were cut in half.

I look suitably humble.

Petra with class of 2015

August 17, 2015

How We Won The War–and Those Other Guys Didn’t

The building where the Gestapo tortured, maimed, and killed hundreds of French men and women, and from where thousands were dispatched to gas chambers in the east, sits at fourteen avenue Berthelot near the River Rhone in central Lyon.

Lingering beneath the cooling plane trees lining the courtyard outside a structure that was originally a health college run by the military, it is not difficult to imagine trucks pulling up to disgorge prisoners into the interrogation rooms and dungeons run by the notorious Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyon. There are not a lot of distractions as you sit here; few visitors come to what is now Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation or, in English, simply the Museum of the Resistance.

If the history of war is written by the victors, the victors also get to create the museums and the memorials dedicated to those wars. In Britain, visits to Bletchley Park outside London, and the Churchill War Rooms, not far from Westminster, leave no doubt as to who won World War II.

The French at the Museum of the Resistance are less certain. They resisted, unquestionably, as the war went on, and Lyon was a center of that resistance.

But the museum must deal with a darker, more complicated reality: a covenant with the Third Reich that allowed the Vichy government to maintain control of southern France after the defeat of the French army in 1940; the dictatorial anti-Semite, Marshal Pétain, who ran Vichy, and had no trouble announcing that the Jews were responsible for the defeat of France; a population that had even less trouble believing him. As the museum points out, it was not the Germans who rounded up Jewish citizens. They didn’t have to. The French did most of the rounding up and deporting for them.

The British don’t have to deal with these unpleasant facts of history—or do they? This summer, Britain was rocked by ancient black and white footage showing then Princess Elizabeth, her mother, and her sister, Margaret, in 1933 practicing their Nazi salutes, egged on by a happily enthusiastic Uncle Edward, who didn’t think the Third Reich was such a bad idea.

The British don’t have to deal with these unpleasant facts of history—or do they? This summer, Britain was rocked by ancient black and white footage showing then Princess Elizabeth, her mother, and her sister, Margaret, in 1933 practicing their Nazi salutes, egged on by a happily enthusiastic Uncle Edward, who didn’t think the Third Reich was such a bad idea.

No sooner had the Nazi salute controversy flared, than Britain’s Channel 4 broadcast a documentary on Prince Philip, the Queen’s husband, featuring a photo of him marching at his sister’s funeral with Nazi officers in full uniform. Turns out three of his sisters married German aristocrats who became top Nazis. One sister, Sophie, was pictured at Hermann Goering’s wedding, seated opposite Hitler.

The controversies swirling around the Royal family’s German ties, the close proximity of the sites where history unfolded, all of it has the effect of reminding a visitor just how close the Second World War remains here seventy years after its end.

In North America, the war tends to fade into the background. In Britain, it remains an ever-present reality—and a popular one at that.

On a hot, humid July afternoon the crowds line up down the block from the impressive bronze entranceway of what are now called The Churchill War Rooms located beside the Clive Steps next to the Treasury Building in Whitehall.

Surprisingly, there are large numbers of millennials for whom the world wars started by their grandparents shouldn’t hold much interest. But all ages and nationalities push through the cramped rooms where Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his cabinet huddled underground during the worst days of the Blitz. The rooms on display are a mixture of what was originally there and what has been recreated since they opened to the public in 1984 (the Churchill bedroom had to be reconstructed; it had been used for years as a storage area).

Visiting the site, you are overwhelmed by the sheer size and complexity of the effort to defeat the Nazis, particularly when peering into the map room where a small band of men and women gathered information and somehow kept track of a conflict that literally raged around the world, more or less held together by a lot of colored pins poked into a big wall map. High tech is not exactly a word that comes to mind when visiting the war rooms.

It doesn’t even fly off the tongue at Bletchley Park where another band of stout-hearted Brits broke the Nazi codes and thus, according to what they tell you at the park, shortened the war by at least two years—“The geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled,” as Churchill memorably put it.

The crowd poking through The Mansion, the headquarters pile built in 1870, is older, much closer to their parents’ war than the kids lined up outside the Churchill rooms. But then the Bletchley estate isn’t easily reached, located in Buckinghamshire, an hour’s drive through a series of roundabouts outside London. What’s more, the men and women who worked here were unknown for nearly thirty years after the war.

Even now, the reason most people visit the park on a perfect summer afternoon, has a great deal to do with the popularity of The Imitation Game, the Academy Award-nominated film about Alan Turing, the conflicted genius who helped create the massive computer, the Bombe, that could quickly break German codes and led to the computer age of which we are all forever a part.

Even now, the reason most people visit the park on a perfect summer afternoon, has a great deal to do with the popularity of The Imitation Game, the Academy Award-nominated film about Alan Turing, the conflicted genius who helped create the massive computer, the Bombe, that could quickly break German codes and led to the computer age of which we are all forever a part.

Turing is barely mentioned in either the story about the effort to break the German codes presented by the park or by the guide who shepherds us through a tour of the facility.

In fact, it becomes clear after a few hours at Bletchley that a great deal of The Imitation Game is well-done fiction: no Russian spies, no Eureka moments, and a lot of Poles who played an important part in creating the machines that broke the German Enigma codes.

However, the Bletchley overseers are well aware that the movie, to paraphrase Churchill, is the modern-day equivalent of the goose that laid a golden egg of publicity. Thus, not only is there no effort to confront the falsehoods of The Imitation Game, the movie is actually celebrated with an exhibit of costumes and a couple of sets used when the production filmed inside The Mansion.

The truth of Bletchley is much more complex than any film depiction. No matter how much you read about how they went about it, the whole business of breaking the Enigma codes still leaves most of us scratching our heads. But thankfully, a lot of people knew what they were doing. By war’s end, close to ten thousand people were working at Bletchley, codebreaking on an industrial scale. You cannot help but be impressed by the level of dedication, the breadth of the cunning, and the absolute determination it took to do what they did.

Back at the Museum of the Resistance in Lyon, one leaves the various exhibits and returns to a shadowy courtyard less certain of cunning and determination. Instead, there is a gloomy sense of the immense waste of the war, the brutal and unending ways in which it managed to take so many millions of lives. In today’s world, the fundamentalist killers of the East are the barbarians, but they have nothing on what the Europeans did to one another through two wars of the world over a span of less than thirty years.

Exiting fourteen avenue Berthelot, you think over the experience of the Imperial War Museum, Bletchley Park, the Churchill War Rooms, arriving at the uneasy and unheroic conclusion that there is peace in the Western World largely because an entire continent finally exhausted itself killing one another.

The victors don’t advertise that part so much.

July 28, 2015

Gone London

The London of Dickens, the London of countless Masterpiece Theatre portrayals, the black and white London of the British movies of my youth—in other words the traditional London that tourists flock here to experience, that London is fast disappearing.

At the bottom of Portobello Road the jaws of a mechanical monster right out of a CGI-infested superhero movie chew into the ruins of a long-standing structure. Luxury flats are to be built in place of what’s there now. The rich have arrived, and they are demanding changes to the landscape.

In his informative non-fiction book, Portobello Road: Lives of a Neighbourhood, author and resident Julian Mash laments the continuing gentrification of this most iconic London neighborhood.

“Shops that had been a feature of the street for decades,” he writes, “were being forced out by huge rent hikes, replaced by impersonal high street chains.”

All over the city similar complaints are heard as local residents fight various luxury developments that threaten the uniqueness of their neighborhoods. The battle is mostly futile. Luxury is winning the war at the expense of historic London.

This is certainly evident at Arnold Circus in London’s East End, not far from Brick Lane. When they were built in 1890, the dramatic brick buildings surrounding the circular park with a bandstand at its center, formed the first so-called council estates—what we would call in North America, affordable housing. Today, although there is some council housing, flats in these buildings sell for prices nudging toward a million American dollars.

To be sure there are still lots of the monuments one associates with London. You can’t get rid of those. No tourist wants to stare at blocks of new Mayfair flats he or she can’t get into. So Buckingham Palace, the Queen’s London digs, is still here, as is Kensington Palace where Kate and William reside along with Prince Harry.

The Houses of Parliament at Westminster Palace loom impressively as does the Tower Bridge, Big Ben, Westminster Abbey, and the best-known symbol of London, the double-decker red bus.

The West End continues to be synonymous with theatre, and it is still exciting to cross Piccadilly Circus in the evening to attend a show like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime. Disappointingly, though, as they do everywhere else, unimaginative juke box-type American musicals reign—Michael Jackson and Frank Sinatra are both dead, but somehow still alive on West End stages.

St. Paul’s Cathedral, which survived German bombs during the Blitz, fights a losing battle against the colossal totems to modernity rising around it, homages to the architecture of Dubai, with derisive nick-names like the Shard, Cheese Grater, the Gherkin, and the Walkie Talkie.

And this is by no means the end of it.

According to the Guardian newspaper, two hundred and thirty new towers are due for construction in the coming years. “Like a cigarette butt stubbed out by the Thames,” is how the Guardian describes one of the proposed towers.

“The overall impression is of an unplanned free-for-all,” says the newspaper.

Carnaby Street is a tourist trap. Harrods, choked with tourists, looks more and more like any other high-end department store, so does Selfridge’s. The posh shops along Mayfair and Bond Street have been taken over by the luxury brand names you can find in just about any major city.

The average price of a London home has soared to five hundred thousand pounds, nearly one million American dollars. And that’s the average. London, as everyone points out, is increasingly for the world’s very rich, and the rich crave luxury.

The city is doing its best to provide it. The Victoria and Albert Museum even devotes an entire exhibit dedicated to the investigation of the subject.

“Luxury has a long history of controversy,” the exhibit points out. “More recently, the increase in prominence and growth of luxury brands against a backdrop of social inequality has raised new questions about what the term means to people today.”

The exhibit argues that luxury is the result of an investment of time and skill by dedicated artists passionate about what they create. It is the uniqueness of their products and their quality that makes them objects of luxury.

Fair enough, one supposes, but—and the exhibit makes less of this—cost increasingly replaces craftsmanship and uniqueness as an arbitrator of modern-day luxury. The luxurious flats are smaller, the soles come off the Marc Jacob shoes, the Gucci watches don’t work, the five star hotels nickel and dime guests to death.

What used to be affordable isn’t, and so just about everything in London becomes something of a luxury that fewer and fewer people can afford. In order to escape this and perhaps find a more recognizable England, one climbs aboard a high-speed train (also a luxury) at St. Pancreas Station that whisks you southeast to the bucolic delights of country living in Ashford, Chilham, and Charing in Kent.

Yet even on the rolling green (a trifle brownish, actually, due to lack of rain) of the Kentish countryside, tradition is harder to find. My friend and local guide, Ray Bennett, grew up in Ashford and he says that so much has changed since he was a boy, he barely recognizes the place. The steeple of the church where he married many years ago used to dominate the town. Now it’s barely visible.

Down the road, Charing features a traditional high street where a friend occupies a small, charming English house fronting an English garden dominated by a bay leaf tree and overflowing with flowers and herbs. Here one has a brief sense of the England of clichéd imagination. That sense is amplified by lunch at the sort of—there is that word again—traditional pub one still expects to find in Britain, and often does.

Then it’s off to Leeds Castle where the English continue to do what so few of us do in North America, maintain and celebrate historic roots. Of course in the cradle of western civilization—at least the English section of it—there are plenty of roots to maintain.

Leeds Castle, according to faithful guide Bennett, is one of Britain’s most beautiful castles. What’s more, it provides a combination of Wolf Hall and Downton Abbey for the visitor with limited time, evidence conveniently gathered under one roof, so to speak, that the rich through the centuries lived a lot better than the rest of us. There are not, as it turns out, a whole lot of poor people’s homes available for tours.

First built on an island in the River Len by a Norman baron during the reign of William the Conqueror, Leeds has played many roles throughout history, most prominently as the palace away from the palace of Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Leeds in 1926 fell into the hands of, and was probably saved by, a wealthy Anglo-American heiress, Lady Baillie. It was she who decided that after her death, her beloved Leeds should be enjoyed by anybody with the price of a ticket—which is how they came to allow the likes of me into the place.

Leeds in 1926 fell into the hands of, and was probably saved by, a wealthy Anglo-American heiress, Lady Baillie. It was she who decided that after her death, her beloved Leeds should be enjoyed by anybody with the price of a ticket—which is how they came to allow the likes of me into the place.

You wander out of the castle, pause for a final look at its imposing battlements, and it strikes you: the rich wrote English history, and they preserved their luxurious surroundings so the peasants could see how they lived. Perhaps there is hope for traditional London after all. The new traditional London that is. Hundreds of years from now our children’s children’s children’s children may be able to see where the rich and the ruling once lived.

For the moment, luxury is the multi-million dollar development I pass on the No. 23 bus back to our flat at Trellick Tower. No chance of ever getting into any of that in this lifetime. As the electronic voice on the London tube reminds you just before the doors open: “Mind the gap!”

July 15, 2015

The Hottest Show In London

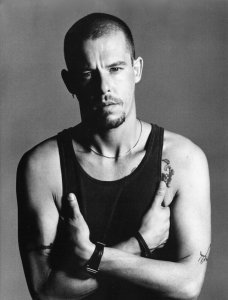

The hottest show in London this summer isn’t playing in the West End. It’s at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty is pretty much sold out through August. If you want tickets, you must book weeks in advance. You are allotted a specific time to view the exhibit, and woe be tide you if you miss the appointed hour.

“Wildly popular,” says Forbes magazine, so wild, in fact, that the museum will remain open around the clock during the last two weekends of Savage Beauty’s run to accommodate the crowds anxious to experience it.

Alexander McQueen was the controversial London-born haut couture designer who worked originally for Givenchy until he started his own Alexander McQueen label in 2001.

Before his suicide in 2010 (high on cocaine and sleeping pills, he hung himself at age 41), McQueen was known as the hooligan of English fashion for the shock and awe he brought to his creations, many, many examples of which are on display at the V and A in a series of interconnected halls, grouped under titles such as Romantic Nationalism, focusing on the influence of his Scottish heritage, and Cabinet of Curiosities, the most dramatic in the exhibition, set in a starkly lit, high-ceilinged chamber lined with shelves some of which contain examples of “fetishistic paraphernalia” designed by McQueen. “I find beauty in the grotesque,” he once said.

Before his suicide in 2010 (high on cocaine and sleeping pills, he hung himself at age 41), McQueen was known as the hooligan of English fashion for the shock and awe he brought to his creations, many, many examples of which are on display at the V and A in a series of interconnected halls, grouped under titles such as Romantic Nationalism, focusing on the influence of his Scottish heritage, and Cabinet of Curiosities, the most dramatic in the exhibition, set in a starkly lit, high-ceilinged chamber lined with shelves some of which contain examples of “fetishistic paraphernalia” designed by McQueen. “I find beauty in the grotesque,” he once said.

A good deal of the stuff, as you might imagine in a collection titled Savage Beauty, tilts in the direction of the fetishistic, including mannequin heads encased in zippered black leather hoods. McQueen certainly played on fashion’s wild side, beloved by celebrities like David Bowie, Lady Gaga, and Björk who also played on that side of the fence—although, in fairness, he was also capable of creating sumptuous, exquisitely cut gowns, influenced much more by Cecil Beaton than by S and M.

The exhibition, while not playing down McQueen’s catwalks on the wild side, prefers to dwell on the designer as socially relevant and a political force who took delight in shaking up what the exhibition sees as a staid fashion world.

Another section of the Savage Beauty maze approximates a mud hut, one of McQueen’s many influences being the ancient tribes of Africa (others: everything from Alfred Hitchcock to his love of scuba diving to his hatred of the English treatment of his Scottish forebears). To emphasize the primitive nature of McQueen’s creations during this period of his life, the black leather hoods on the mannequins are gone, replaced by impala horns.

Said McQueen, who grew up, despite claims to the contrary, in a comfortable middle-class British household, and who was a success from the moment he stepped out of Central St. Martins College of Art and Design, “You’re here, you’re gone. It’s a jungle out there.”

Another phase of the McQueen oeuvre isn’t so much influenced by the primitive as the natural—Romantic Naturalism, the exhibition calls it. Nature as a work of art. A dress made of razor clam shells is on display as is one made of pheasant feathers. Another dress is partially constructed of real flowers. “I use flowers,” McQueen explained, “because they die.”

The theatricality of all this is undeniable, but just how seriously are we to take Savage Beauty? Very seriously indeed if you read the gobbledygook narration fed visitors at the V and A., a view avidly promoted by McQueen himself while he was alive: “When I’m dead and gone, people will know that the twenty-first century was started by Alexander McQueen.”

Try as one might, it is difficult to see McQueen as a twenty-first century starter. The exhibit does inadvertently shine a spotlight on high fashion’s pretentiousness, the vast disconnect between what’s celebrated on the catwalks of London and Paris and what ends up in a department store where almost nobody thinks of politics when buying a dress.

If you want a time when fashion politics mattered, one must escape Savage Beauty and head south across the Thames to, of all places, The Imperial War Museum. Fashion on the Ration: Style in the Second World War, examines in exhaustive detail the ways in which women adjusted to fashion amid the deprivations of a world war. Here politics really did play a role, not to mention the influence of falling bombs.

The siren suit, for example, was developed to provide a single, easily worn piece of clothing that could be thrown on when the fashionable ladies of the day had to head for the bomb shelters. It was possibly one of the first pieces of unisex clothing. Winston Churchill loved the siren suit and was often photographed in it.

The siren suit, for example, was developed to provide a single, easily worn piece of clothing that could be thrown on when the fashionable ladies of the day had to head for the bomb shelters. It was possibly one of the first pieces of unisex clothing. Winston Churchill loved the siren suit and was often photographed in it.

Politics stuck its ugly head into fashion in 1941 when the war was going so badly for the British that the government started rationing clothing.

Women were told not to buy anything, but to mend their existing clothing instead. “Make Do and Mend” became the cri de coeur of the day. The government went to great lengths in order to get this point across, producing everything from films to how-to classes in sewing and dress making, using just about anything, including the silk maps provided to bomber navigators.

At the same time, the government worried that women would lose their sex appeal with all these clothing restrictions, thus affecting the morale of the boys returning home. Women on the homefront not only had to maintain a stiff upper lip, but they were also required to put lipstick on it.

“Every woman’s a hero in these days,” announced a contemporary advertisement, “but with an undeniable hint of sex appeal.” Or this: “During these rather difficult days, it is not only a woman’s pleasure to do her best, it is her downright duty.” The propaganda even went so far as to suggest it was treasonous to appear dowdy.

Fashion on the Ration argues that the war and the clothes restrictions it demanded, opened the door to the sort of mass market clothing that fueled the emergence of department stores and led to the democratization of fashion. Yet for all the emphasis on the political and social over at Savage Beauty, nothing about it strikes you as particularly democratic.

Instead, it emphasizes something the World War II industry never had to be concerned with, the here today-unfashionable tomorrow sensibility that now permeates fashion, a sense that the revolution has long since passed, but if you keep changing the clothes and the styles fast enough, and shock the locals every once in a while, no one will notice.

July 10, 2015

London Calling

The Greeks are finished (Eurogeddon!), the Chinese are collapsing, a strike has closed the London underground for the first time in thirteen years, everyone is shocked—shocked!—that a Conservative government would slash welfare benefits in its latest budget and, sadly, it is the tenth anniversary of the bombings that killed thirty-eight people..

Those are the more inconsequential stories one ignores in the rush to devour the much more important news here in the United Kingdom. The wife of a British MP, notorious for posting selfies on-line showing off a now famous décolletage, has been accused by her husband of having an affair with her trainer. Her husband is reeling; she is denying all.

Singer Lily Allen has been photographed wasted and unconscious in a field at the Glastonbury Music Festival. No, I’ve never heard of her either, but she previously had been photographed at Glastonbury in a plastic penis costume—and no, I’m not making this up.

And, of course, there is the biggest British story of them all, the christening of royal baby Charlotte: “Spirits of Diana guides Charlotte’s christening,” reports the Sunday Times.

Arriving in town on the eve of Eurogeddon, I know little of Greek economics and absolutely nothing about cheating politicians’ wives (Canadian scandals have nothing to do with anything as interesting as sex), or wasted pop singers (except Amy, the controversial film documentary about singer Amy Winehouse that has just opened here).

My intention in being in London for the next month is no more serious than getting to know better a city I have visited often without spending any real time here. While my wife Kathy takes a course at Central St. Martins, a leading school of art and design, my plan is to explore London, with help from my longtime comrade-in-arms, Ray Bennett, editor, journalist, budding author,and London expert extraordinaire.

My intention in being in London for the next month is no more serious than getting to know better a city I have visited often without spending any real time here. While my wife Kathy takes a course at Central St. Martins, a leading school of art and design, my plan is to explore London, with help from my longtime comrade-in-arms, Ray Bennett, editor, journalist, budding author,and London expert extraordinaire.

Bennett, promptly on the job, whisks me off to the British Film Institute where a morning press conference has been called to present an ambitious program reviving British film, everything from documentaries to features, to home movies. Watching excerpts from the home movies—locals cross-dressing, kids rolling tires down embankments—as well as the carry-on-Britain-stiff-upper-lip documentaries, Bennett leans over and whispers, “No wonder Monty Python came out of this.”

Absolutely right.

My idea of living in London is a lovely terrace flat in Regent’s Park, the sort of place where the inhabitants of Downton Abbey might be found while popping into the city for a visit. Unfortunately, you must be in charge of one of the oil emirates these days to afford that sort of accommodation. Instead, we have headquartered ourselves not far from Portobello Road.

I thought we were in Notting Hill, but, as I usually am when it comes to geography, I am wrong. We have rented an apartment at the somewhat legendary Trellick Tower in the Royal Burrough of Kensington and Chelsea.

You can’t miss Trellick Tower on the landscape around here; it, well, towers over everything, thirty-two stories in height, looking like, depending on the limits of your imagination and the angle from which you view the building, either an exposed computer circuit board attached to an ancient aboriginal totem or an art deco masterpiece imprisoned in a German expressionist nightmare by Fritz Lang.

Some unkind folks deem it plain ugly and an eyesore in the neighborhood, and it is, to be honest, as is noted in its Wikipedia entry, “a little rough around the edges.”

Like most things in London, Trellick Tower comes with history. Its design rose from the imagination of the Hungarian architect Ernő Goldfinger—and yes, Ian Fleming got into a discussion with Goldfinger’s cousin on the golf course and the next thing the author titled his latest James Bond novel, Goldfinger.

You have only to stand in front of Trellick Tower to realize Goldfinger had no sense of humor (he even tried to sue Fleming for using his name; he got six free copies of the novel, instead). The tower was one of a number of structures he designed to help alleviate the post-World War II housing shortage.

Goldfinger created his building blocks in the Brutalist style, from the French béton brut or raw concrete, popular with governments in the 1950s, but not a big hit with the people who had to live in them.

Originally, Trellick Tower was made up of so-called council flats, what in North America would be termed affordable housing. In the 1970s, the block had a reputation for crime and violence. People refused to live there.

After a time, however, flats were made available for sale and that helped to transform the building. Depending on who you talk to, Trellick Tower now is either a trendy address where apartments are going for as much as a million dollars or a real estate nightmare full of flats that aren’t selling.

Certainly it is now a local landmark, designated a listed building, that is a structure of special architectural and historical interest. Numerous movies have been shot here, T-shirts display the tower, and the British rock band, Blur, featured Trellick Tower in a song (“Trellick Tower is calling…”).

Certainly it is now a local landmark, designated a listed building, that is a structure of special architectural and historical interest. Numerous movies have been shot here, T-shirts display the tower, and the British rock band, Blur, featured Trellick Tower in a song (“Trellick Tower is calling…”).

For me it’s a fascinating place to spend the next month, with a breath-taking view of London from our pleasant twenty-seventh floor apartment, a colorfully diverse community, a cacophony of languages, and a warm welcome for a couple of Canadian interlopers.

There are remnants of its bad old days. A sign by the elevators warns the person who has been spitting on the floor that CCTV security cameras are now installed, and the miscreant can be identified.

I have taken the warning under advisement as I await the day’s tabloids with the latest news of the British MP’s wife who is messing around with her trainer. Nothing more on the pop star who passed out at Glastonbury. The Greek financial crisis? What Greek financial crisis? And what are the Chinese going on about, anyway?

July 7, 2015

Send In the Rolls-Royce Corniche: Remembering Jerry Weintraub

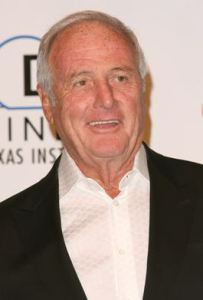

One of the perks of working for Hollywood producer Jerry Weintraub, who died yesterday at the age of 77, was that he sent his convertible Rolls-Royce Corniche to pick you up at the airport, complete with immaculately uniformed chauffeur.

Jerry was a movie mogul in the old style, a throwback to the kind of larger-than-life character who once ruled the movie business, but who had become an endangered species.

There was nothing endangered about Jerry. When I met him, he had produced hits like Nashville and The Karate Kid. He was considered to have the magic touch when it came to choosing movies, so magical in fact that he had decided to establish his own independent production company, the Weintraub Entertainment Group, with hundreds of millions invested by such stalwart brands as Coca-Cola and the Bank of America. The largest privately funded startup in movie history, according to the Hollywood Reporter. Everyone believed in Jerry; Jerry produced hits.

In the midst of establishing his company and getting something like six productions off the ground, Jerry was celebrating his fiftieth birthday, and writing his memoirs. Well, he wasn’t actually going to write them. He hired me to do that. Jerry would talk. I would write.

The Rolls-Royce Corniche was at the airport to pick me up.

Jerry was impossible not to like. He yelled at a lot of people while I was around, but he never yelled at me. Not that there was a lot to yell about. One of the problems of writing Jerry’s autobiography, it turned out, was Jerry. He wanted to do the book, he said. He just didn’t seem to have a whole lot of time to do it.

Initially, there was the preoccupation with that fiftieth birthday party. Jerry’s original success had come in the music business where he had promoted concerts for everyone from Sinatra to Elvis to Bob Dylan. He was already rich by the time he got into films, thus fulfilling the maxim that if you want to make a little money in the movie business, you should start out with a lot.

He owned homes in Beverly Hills, Malibu, New York, and in Kennebunkport, Maine, where he could be close to his friend, Number Forty-One himself, President George W. Bush. However, since Forty-One could not be there, it was decided to throw the birthday party at Jerry’s twenty-two acre seaside estate in Malibu.

I have been to a lot of celebrity-studded parties, but it’s safe to say I have never been to a party with the number of celebrities who turned out to celebrate Jerry that night. Everywhere you looked as you strolled around the grounds, there was another A-lister.

Sidney Poitier embraced Jerry. Dallas’s Larry Hagman wandered past, followed by director Sydney Pollack, still basking in the Oscar-afterglow of Out of Africa. Neil Diamond was there, and so was James Caan. Jacqueline Bisset danced with her then-boyfriend, ballet dancer Alexander Godunov. I ended up standing in the dinner line chatting with Johnny Carson and his wife Alexis Maas. Ed McMahon came along to say hello.

It was that kind of party.

By this time, guests had been drinking hard for over two hours, so that as we finally got seated, everyone was—no other way to put it—drunk as a skunk. The actor Lee Majors, whom I had known from Toronto, weaved past, squinted at me, and made noises that sounded like, “Don’t I know you?”

Like I said, it was that kind of party.

The next day, Jerry, looking fresh and unaffected by the previous night’s revels, entertained me in his office, his leg propped up on his desk, foot bared, each of his toes separated by tufts of cotton batting. Jerry was having a pedicure.

As the manicurist worked on his foot, he began to talk about his early life, his time in the U.S. Air Force in Alaska, always hustling even way back then. Pretty good stuff; Jerry was never less than interesting. After a few minutes, he stopped, and looked perplexed. “Jeez, Ron,” he said. “How long is this book gonna take?”

I gently pointed out that we had only nicely started. He didn’t look happy but he did talk for a few minutes more before he had to go off to a meeting. I retreated to the office they had given me, a vast space across the street from Jerry. This was supposed to be where the writers Jerry hired would work. Except there were no writers. Only me. Everyone else had gone on strike. Sitting all alone amid the emptiness, I had my first inkling that all was not right with Weintraub Entertainment.

I began to wonder what was going on. I continued to wonder as I lay around the pool at the Beverly Comstock, the Beverly Hills apartment hotel where I was being put up in great comfort. Every so often I would phone Jerry and say something like, “Gee, Jerry, we’re never going to get this book done.”

He would say something like, “We’ll get it done, Ron. Don’t worry.”

And every once in a while, Jerry would start to feel guilty about me getting sunburned in Beverly Hills, so we would sit around his pool and he would talk. Not for long. He had an empire to run, movies to release.

Ah, yes. The movies. The hit movies. The first of those hits rolled out: Le Grand Bleu, a French film Jerry recut and released in the U.S. as The Big Blue. It was not a hit. The second movie, the first original production out of WEG, starred Molly Ringwald and was titled Fresh Horses. It was not a hit, either.

There were a couple of other releases and they also came and went with hardly a ripple at the box office. Everyone at WEG said not to worry, there was a movie in the can that was a surefire hit. It starred Dan Aykroyd and Kim Basinger, a comedy titled My Stepmother Is An Alien. Kim Basinger was the alien. It couldn’t miss.

The next thing, I couldn’t get hold of Jerry. Everything was fine, I was told. Fly to Kennebunkport. Jerry will talk to you there. I flew to Kennebunkport. This time there was no Rolls-Royce with a chauffeur at the airport. I checked into a rustic hotel just down the road from George Bush’s place that didn’t have a television in the room. The guy behind the desk looked unhappy when I insisted on one.

I lay around the pool at Kennebunkport. Waiting. And waiting. Finally, I got a call from Jerry’s wife, the singer Jane Morgan. Jerry wasn’t in Kennebunkport. Go home. Jerry will be in touch.

Jerry never got in touch. My Stepmother Is An Alien, the surefire hit, wasn’t. Instead of making hits, Jerry had produced a series of bombs. Cola-Cola unceremoniously pulled the plug on its financing, so did The Bank of America, and Weintraub Entertainment Group was gone.

As was Jerry’s autobiography. After all, who wants to read a book about a guy who makes a bunch of bad movies and whose company has just gone bankrupt?

I worried about what would happen to Jerry. I should have known better. Their companies may go under, but guys like Jerry Weintraub always survive. He hung in there, eventually produced the Ocean’s Eleven films and was more or less back on top, although I always thought his gift for self-promotion outran his ability to get movies made into today’s Hollywood.

I worried about what would happen to Jerry. I should have known better. Their companies may go under, but guys like Jerry Weintraub always survive. He hung in there, eventually produced the Ocean’s Eleven films and was more or less back on top, although I always thought his gift for self-promotion outran his ability to get movies made into today’s Hollywood.

He even finally published his autobiography, although I had nothing to do with it. In interviews promoting his book, he said he previously had considered writing about his life, but decided he was too young.

Well, there you go. Truth in Hollywood. Still, when I heard of his death, I sat in faraway London, England, experiencing a series of complicated emotions about my time with him. Mostly, though, I remembered him fondly. After all, how many people in your life send a chauffeured Rolls-Royce Corniche to pick you up at the airport?

July 2, 2015

Black Snake: The Forgotten Life of George Raft

Please click HERE to download The Confidence Man

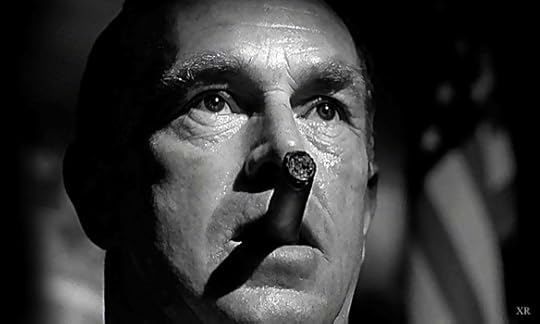

The difference between Humphrey Bogart and George Raft came down to this: Bogey was an actor; Raft was a gangster. Bogart acted tough. Raft was tough. Raft conspired to ensure that no one remembered him. Bogey, the phony tough guy, became legend.

Raft was a much more interesting character than Bogart or any of the other stars on the Warner Bros. lot in the heyday of the studio system during the 1930s and 1940s. I became fascinated with him while researching a book on movie stardom, If The Other Guy Isn’t Jack Nicholson, I’ve Got the Part. I thoroughly researched his life in Hollywood and talked at length to one of his biographers, Lewis Yablonsky, who spent a lot of time with Raft before he died.

I was so fascinated that I cast Raft in a pivotal role in The Confidence Man, my novel of Hollywood in 1928 as movies began to talk. In the book, Raft plays the role he played in real life when he first arrived in Los Angeles– the New York hoodlum who grew up in Hell’s Kitchen (his real name was George Ranft) with his pals Owney Madden and Ben “Bugsy” Siegel, notorious gangsters who were his lifelong friends.

James Cagney, also from New York, and a fellow traveler on the Warner Bros. lot, thought Raft was the toughest guy he ever met. Before he became a movie star, Raft worked variously as a baseball player, boxer, and most successfully as a taxi dancer who specialized in the tango. He had glossy black hair and a ferret-like face that showed no emotion, that hid everything. Edward G. Robinson, another New Yorker, called Raft’s face, “a fantastic, arresting mask.”

He was always beautifully dressed, and he popularized the idea of wearing a white tie with a black shirt. He married only once to a woman he claimed he never made love to. Nonetheless, around Hollywood, he was known as the Black Snake because of the size of his penis and was said to make love to as many as three women a day. He had affairs with Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Betty Grable, among others, but refused to divorce the wife he never made love to.

Owney Madden bankrolled Raft in Hollywood, thinking it would be great to have a mob guy in the movies. Director Howard Hawks cast him in his 1932 production of Scarface opposite Paul Muni. Raft came on the screen flipping a nickel. It was Hawks’ idea, but it became a trademark for Raft.

By 1937, under contract at Paramount Pictures, Raft was the star Owney Madden hoped he would be, making over two hundred thousand dollars a year, the third highest paid actor in the industry (behind Warner Baxter, the original Cisco Kid, and Gary Cooper). But he was always the outsider in Hollywood, uneasy about his abilities, and increasingly unwilling to be in the movies what he was in life—a gangster.

“If you’re a meany in every role,” he said, “the people back in Deep Sleep, Wyoming get to think you’re that kind of guy.”

That mindset led the Black Snake to turn down the roles that made Humphrey Bogart a star and transformed a short, balding former Broadway actor who had been trapped in Warner Bros. B movies into a celluloid icon.

Raft’s mistakes began piling up when producer Samuel Goldwyn, mounting a movie version of the Broadway hit, Dead End, wanted him for the role of Baby Face Martin, a psychopathic gangster. When he read the script, Raft was appalled. This was precisely the sort of character he didn’t want to play.

The role went instead to Bogart, and put him on the road to stardom. By now, Raft had arrived at Warner Bros., the last place he should have landed if he didn’t want to play ‘meanies.’ Warner Bros. specialized in them.

Studio boss Jack Warner became convinced that Raft couldn’t read, and that’s why he ended up turning down so many parts. He refused to play the heroic seaman who takes on a brutal captain (played by Edward G. Robinson) in a screen adaptation of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf. The part of the seaman went to an unknown named John Garfield who became a star, thanks largely to the movie. Thus the stage was set for what producer Hal Wallis described as Raft’s two decisions that “finally sank his career.” Those decisions are now part of movie lore, about the only reasons the Black Snake is remembered at all these days.

It was John Huston, then a novice screenwriter at Warners, who suggested the studio film W.R. Burnett’s novel, High Sierra. The story concerned the last days of an aging mobster named Roy “Mad Dog” Earle. Jack Warner assigned no-nonsense Raoul Walsh to direct, and Walsh immediately thought of Raft for Earle. To everyone’s amazement—although by then they should have known better—Raft said no.

It was John Huston, then a novice screenwriter at Warners, who suggested the studio film W.R. Burnett’s novel, High Sierra. The story concerned the last days of an aging mobster named Roy “Mad Dog” Earle. Jack Warner assigned no-nonsense Raoul Walsh to direct, and Walsh immediately thought of Raft for Earle. To everyone’s amazement—although by then they should have known better—Raft said no.

Walsh went around to talk to him. “I’m not going to die,” Raft insisted.

“But you have to die,” Walsh argued. “You’re a baddie who killed two people. The censors won’t go for it unless we knock you off.”

Raft was the last actor in the world who wanted to play someone who killed two people and then died for it. “Tell Jack Warner to shove it,” the Black Snake snarled.

In fairness, just about every star on the Warners lot turned down the part. Finally, out of desperation, Walsh turned to Bogart. He said yes, and thus High Sierra marked the turning point in his career. “The performance made him a star,” Walsh later said.

Worse was yet to come. John Huston had found another book he liked. This one was a mystery about a hard-boiled San Francisco private detective named Sam Spade. It was called The Maltese Falcon, and Huston not only wanted to write it, he also wanted to direct. Since it already had been filmed twice at Warner Bros., dismal efforts both times, Warner wasn’t particularly interested in a third picture.

Nonetheless, another version could be done cheaply so Jack Warner allowed Huston to both write and direct The Maltese Falcon. This time, Raft wasn’t asked. He was simply assigned to play Spade. The first Raft knew of the movie was when the script arrived at his door. Not surprisingly, the day Raft was to appear for wardrobe tests, he never showed.

Four days before The Maltese Falcon started shooting, Raft sent Jack Warner a note: “As you know, I feel strongly that The Maltese Falcon…is not an important picture and, in this connection, I must remind you again…you promised me that you would not require me to perform in anything but important pictures.”

Thus Huston was able to turn to the actor he had wanted all along for Spade: Humphrey Bogart. Not only was the movie a critical hit and unexpected commercial success when it was released in 1941, but after years of toiling in the Warner Bros. factory, it made Humphrey Bogart a star.

There was some talk about Raft doing Casablanca, and Raft told his biographer Lewis Yablonsky that he turned down the part of Rick Blaine because it wasn’t right for him. His final dumb move, if that was the case.

However, it’s probably not true. By that time, the studio was fed up with Raft and sold on Bogart. According to Aljean Harmetz in Round Up the Usual Suspects, her riveting book about the making of Casablanca, no one at Warner Bros. seriously considered anyone else. For the record, Raft didn’t just turn down Bogart movies. Subsequently, he said no to Billy Wilder who wanted him for Double Indemnity. The role went to Fred MacMurray; the movie became a film noir classic.

By the 1950s, after a series of increasingly mediocre and unsuccessful pictures, George Raft was pretty much washed up, remembered less as a movie star and more for what he wanted everyone to forget—his gangster past. He never gave up his mob connections, though, and there was one consolation: Because he did not smoke or drink, he long outlived Humphrey Bogart, dying in 1980 at the age of eighty-five.

However, the Black Snake could never outlive Bogart’s legend, the legend that might have been his, if only he had said yes when he said no.

For more on George Raft in The Confidence Man please click HERE.

June 23, 2015

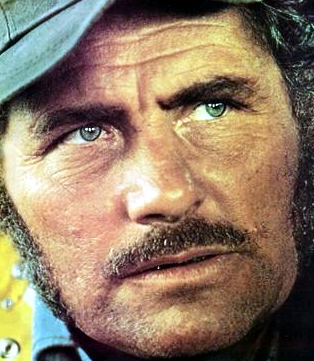

At Barney’s Beanery With the Guy Who Created Jaws

In the years I lived in Los Angeles, I occasionally hung out at a legendary West Hollywood eatery called Barney’s Beanery. Mostly, I sat with screenwriters in late middle age, all of us grumbling about the state of a movie industry that either wasn’t interested (in my case) or had moved on to younger writers (most of the others present).

In the years I lived in Los Angeles, I occasionally hung out at a legendary West Hollywood eatery called Barney’s Beanery. Mostly, I sat with screenwriters in late middle age, all of us grumbling about the state of a movie industry that either wasn’t interested (in my case) or had moved on to younger writers (most of the others present).

One of those who showed up from time to time was a writer named Carl Gottlieb. Carl wasn’t standoffish, but he was quiet, and, despite his scruffy appearance, he gave the impression there was something about him a little more important than the rest of us lesser mortals. That turned out in its Hollywood way, to be true.

Carl was the principal screenwriter of Jaws, the groundbreaking 1975 classic that established Steven Spielberg as a director and forever changed the way movies are made and marketed—a fact that has been pounded to death in the last week or so as Jaws celebrates the fortieth anniversary of its release.

During our encounters at Barney’s the subject of Jaws never came up. But when I was writing a book about movie stardom titled If the Other Guy Isn’t Jack Nicholson, I’ve Got the Part, I got in touch with Carl and spoke to him at length about his involvement in the movie. To this day, he remains the film’s unsung hero, next to Spielberg the guy most responsible for the movie’s success.

During our encounters at Barney’s the subject of Jaws never came up. But when I was writing a book about movie stardom titled If the Other Guy Isn’t Jack Nicholson, I’ve Got the Part, I got in touch with Carl and spoke to him at length about his involvement in the movie. To this day, he remains the film’s unsung hero, next to Spielberg the guy most responsible for the movie’s success.

Carl said his involvement with Jaws began one Sunday afternoon when he got a call from his friend Spielberg. Carl had kicked around Hollywood for a while, working as both an actor and a comedian, but at that point he had no screenwriting credentials. Spielberg, who was twenty-six at time, said he wanted to get together at the Bel Air Hotel. Carl knew his friend was to direct a film based on the Peter Benchley bestseller titled Jaws, about a great white shark terrorizing a New England town. In fact, he had already read the early screenplays by Benchley, so he was willing to take the meeting. When did Steven want to get together?

Now, said Spielberg.

When Carl arrived at the hotel, he found Spielberg with Richard Zanuck and David Brown, the producers of Jaws. Nobody was happy with the script, and production was about to begin on Martha’s Vineyard. Universal Studios thought of this as nothing more than another disaster movie in the style of the prefabricated products such as Earthquake and Airport 1975 the studio had been profitably churning out.

When Carl arrived at the hotel, he found Spielberg with Richard Zanuck and David Brown, the producers of Jaws. Nobody was happy with the script, and production was about to begin on Martha’s Vineyard. Universal Studios thought of this as nothing more than another disaster movie in the style of the prefabricated products such as Earthquake and Airport 1975 the studio had been profitably churning out.

Spielberg and the producers had different ideas, however. Did Gottlieb have any suggestions how the script might be improved so as to get it away from the usual disaster movie clichés? Drop the Mafia subplot that was in the book, Carl immediately suggested.

The producers liked that, and so the next thing Carl knew he was sharing a rented house on Martha’s Vineyard with Spielberg, daily rewriting the script and helping with the casting of the movie. Carl, for example, pushed hard to hire veteran actor Sterling Hayden, best known for John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, and Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove to play the part of Quint, the half-mad fishing boat captain enlisted to go after the great white.

A former schooner captain who had run away to the sea at the age of sixteen, Hayden seemed perfect for the role. However, he was having tax problems with the Internal Revenue Service and couldn’t come to the U.S. from the houseboat he occupied in Paris on the River Seine. There was also talk of Lee Marvin as Quint, but no one associated with the production could quite remember if a formal offer was ever made. Zanuck and Brown, having worked with the British actor Robert Shaw on The Sting, decided to go with him.

Joel Grey, who had recently won an Oscar for his role in Cabaret, was lobbying hard for the role of the marine biologist. However, Carl and Spielberg were friends with Richard Dreyfuss who had recently broken through in American Graffiti and The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. They wanted him.

The problem was, Dreyfuss had already twice turned down this “fish story.” Carl got on the phone with him. “It’s all rewritten, it’s all changed,” he reassured the actor.

Dreyfuss was in the middle of travelling around promoting Duddy Kravitz, but he agreed to get on a shuttle and come to Martha’s Vineyard for a meeting. “As soon as he walked in the room,” Carl remembered, “he had that beard, those glasses, that hat—the same as the movie—and he was the character.”

There has been debate over the years about who provided the film’s most famous scene: On the eve of the final shark attack, Quint describes the torpedoing of the destroyer Indianapolis during the Second World War and the subsequent mass shark attack that decimated the ship’s survivors.

Carl said it was the playwright Howard Sackler, himself an avid sailor, who remembered the Indianapolis incident, and used it in the first version of the script written with Benchley. Carl liked the reference and as Spielberg approached the filming of the climatic sequence, he lobbied the director to include the Indianapolis reference in the sort of lull-before-the-storm speech that was a mainstay of so many of the war films he had watched over the years.

Shaw, a playwright himself, was not happy with the scene despite efforts to bring it to life from both John Milius (who wrote Apocalypse Now) and George Lucas. Finally, the night before the scene was to be shot, Shaw gathered together the various versions, took them away and distilled everything into a single page which he presented to Carl, Dreyfuss, and Spielberg after dinner. With lights dimmed, Shaw acted out the scene for them. Everyone sat in stunned silence when he finished. Carl said not a word was changed when Spielberg shot the scene the next day.

Shaw, a playwright himself, was not happy with the scene despite efforts to bring it to life from both John Milius (who wrote Apocalypse Now) and George Lucas. Finally, the night before the scene was to be shot, Shaw gathered together the various versions, took them away and distilled everything into a single page which he presented to Carl, Dreyfuss, and Spielberg after dinner. With lights dimmed, Shaw acted out the scene for them. Everyone sat in stunned silence when he finished. Carl said not a word was changed when Spielberg shot the scene the next day.