David Tickner's Blog, page 38

December 9, 2020

Answer

Did you ever wonder why there is a silent ‘w’ in the word answer?

The word answer has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) swer (to speak, talk, say) and Proto-Germanic swerjanan (the source of Old Saxon swerian, Old Norse sverja, Danish sverge, Middle Dutch swaren, Old High German swerien, and others). From these sources comes Old English swerian (to take an oath), Old English swaru (affirmation), and later the English word swear. Later, in the early 15th century, the word swear also came to mean ‘bad language’, particularly the use of religious terms as ‘swear words’.

You will have noticed that PIE swer forms the last four letters of the word answer. The ancient PIE word, including the silent ‘w’, is still with us.

The word answer, related to the word swear, comes from Old English andswaru (the reply to a question, a response) from the Old English prefix and- (against; from the PIE root ant meaning front, forehead, in front of, before) + swaru. Originally andswaru likely meant a sworn statement answering to a charge (“Do you swear that you didn’t steal your neighbour’s chicken? What is your andswaru?”).

Later, the word answer, meaning the solution to a problem, is from around 1300.

Answer is a Germanic word. The equivalent English word from Latin is response; that is, Latin re- (back) + spondere (to pledge; spondere is also the root of spouse and responsibility) = respondere (“Do you pledge to take this person to be your spouse? What is your response?”).

Answers and responses both imply that the speaker is ‘swearing’ to tell the truth.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

The word answer has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) swer (to speak, talk, say) and Proto-Germanic swerjanan (the source of Old Saxon swerian, Old Norse sverja, Danish sverge, Middle Dutch swaren, Old High German swerien, and others). From these sources comes Old English swerian (to take an oath), Old English swaru (affirmation), and later the English word swear. Later, in the early 15th century, the word swear also came to mean ‘bad language’, particularly the use of religious terms as ‘swear words’.

You will have noticed that PIE swer forms the last four letters of the word answer. The ancient PIE word, including the silent ‘w’, is still with us.

The word answer, related to the word swear, comes from Old English andswaru (the reply to a question, a response) from the Old English prefix and- (against; from the PIE root ant meaning front, forehead, in front of, before) + swaru. Originally andswaru likely meant a sworn statement answering to a charge (“Do you swear that you didn’t steal your neighbour’s chicken? What is your andswaru?”).

Later, the word answer, meaning the solution to a problem, is from around 1300.

Answer is a Germanic word. The equivalent English word from Latin is response; that is, Latin re- (back) + spondere (to pledge; spondere is also the root of spouse and responsibility) = respondere (“Do you pledge to take this person to be your spouse? What is your response?”).

Answers and responses both imply that the speaker is ‘swearing’ to tell the truth.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on December 09, 2020 19:36

December 6, 2020

Banjo, Rinky-Dink

Banjo

BanjoThe word banjo is of African origin, likely related to Bantu mbanza, a musical instrument resembling a banjo. The word banjo, describing a guitar-like musical instrument with a circular body covered in front with stretched parchment, came to English in 1764. The instrument was also sometimes known as a banjar.

Rinky-dink

Rinky-dink, a term from 1913, is said to be carnival slang imitative of the sound of banjo music.

Earlier, the term rinky-dink in the chorus for a song is seen in an 1896 edition of the Yale Literary Magazine:

“Rinky dinky, rinky dink,

Stand him up for another drink.”

Also, more seriously, around this time the term rinky-dink meant to be robbed. For example, to quote from a story from 1899: “I felt and saw that I was robbed… I found an officer on the corner of 25th Street and 6th Avenue. I said, ‘Officer, I have got the rinky-dink.’ He knew what it meant all right. He said, ‘Where? Down at the wench house?’ I said, ‘I guess that is right’” (from a testimony dated New York, 9 August 1899).

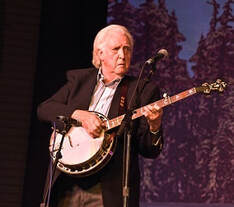

Image: J.D. Crowe (born August 27, 1937, in Lexington, Kentucky) is an American banjo player and bluegrass band leader.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on December 06, 2020 22:39

December 4, 2020

Nerd, Geek

Nerd

Have you ever read or has someone ever read to you the (now somewhat controversial) book by Dr Seuss, If I Ran the Zoo? You may remember these lines…

“And then, just to show them, I’ll sail to Ka-Troo

And bring back an it-kutch, a preep, and a proo,

A nerkie, a nerd, and a seersucker too!”

The book, published in 1950, is credited with being the first use of the word nerd in print. Around this time, nerd was also American student slang said to be related to the slang term nert (stupid or crazy person).

Nert, in turn, is attested from 1903 and may be an alteration of another slang term, ‘nut’. For example, nuts or nutty is often used to describe something crazy. Nut-house (an insane asylum) is from 1929. Nut-case meaning a crazy person is from 1959. The British use the term nutter. Nuts can also mean nonsense.

The first use of the word nuts to mean crazy or not right in the head is from 1846. However, interestingly, nuts meaning ‘to be very fond of’ is from 1785 and meaning ‘any source of pleasure or delight’ is from the 1610s. Perhaps people can seem crazy when they are very fond of someone or something (The word fond is also one of the sources of the word fun; but that’s another story).

In current usage, a nerd is usually a student who is seen as socially inept or slavishly devoted to intellectual or academic pursuits (heaven forbid!).

Geek

The word geek has its origins in Germanic and Scandinavian words meaning to croak or cackle, to mock or cheat; for example, Swedish gacka, German gecken, Dutch gekken. In the 1510s, the work geck came to English meaning a fool or simpleton.

The word geek, meaning a circus sideshow freak, is from 1916 from American carnival and circus slang. For example, a geek was a someone portrayed as a ‘wild man’ or as someone who as part of a circus act bit off (or appeared to bite off) the heads of chickens, snakes, and so on.

By 1983, geek was a slang term for students who often lacked social graces and who were obsessed with new technology and computers.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Have you ever read or has someone ever read to you the (now somewhat controversial) book by Dr Seuss, If I Ran the Zoo? You may remember these lines…

“And then, just to show them, I’ll sail to Ka-Troo

And bring back an it-kutch, a preep, and a proo,

A nerkie, a nerd, and a seersucker too!”

The book, published in 1950, is credited with being the first use of the word nerd in print. Around this time, nerd was also American student slang said to be related to the slang term nert (stupid or crazy person).

Nert, in turn, is attested from 1903 and may be an alteration of another slang term, ‘nut’. For example, nuts or nutty is often used to describe something crazy. Nut-house (an insane asylum) is from 1929. Nut-case meaning a crazy person is from 1959. The British use the term nutter. Nuts can also mean nonsense.

The first use of the word nuts to mean crazy or not right in the head is from 1846. However, interestingly, nuts meaning ‘to be very fond of’ is from 1785 and meaning ‘any source of pleasure or delight’ is from the 1610s. Perhaps people can seem crazy when they are very fond of someone or something (The word fond is also one of the sources of the word fun; but that’s another story).

In current usage, a nerd is usually a student who is seen as socially inept or slavishly devoted to intellectual or academic pursuits (heaven forbid!).

Geek

The word geek has its origins in Germanic and Scandinavian words meaning to croak or cackle, to mock or cheat; for example, Swedish gacka, German gecken, Dutch gekken. In the 1510s, the work geck came to English meaning a fool or simpleton.

The word geek, meaning a circus sideshow freak, is from 1916 from American carnival and circus slang. For example, a geek was a someone portrayed as a ‘wild man’ or as someone who as part of a circus act bit off (or appeared to bite off) the heads of chickens, snakes, and so on.

By 1983, geek was a slang term for students who often lacked social graces and who were obsessed with new technology and computers.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on December 04, 2020 17:31

December 1, 2020

Geologist

The origin of the word geologist could be said to be as old as the rocks themselves! While the origin of the word is unknown, some suggest that it may be found in Dorian, an ancient (i.e., 5,000 – 6,000 years or more ago) pre-Indo-European language of Greece. The Dorian word ga (earth) is presumed to be the source of the Greek word gaia (earth, not heaven; land, not sea; a land, country, soil).

The origin of the word geologist could be said to be as old as the rocks themselves! While the origin of the word is unknown, some suggest that it may be found in Dorian, an ancient (i.e., 5,000 – 6,000 years or more ago) pre-Indo-European language of Greece. The Dorian word ga (earth) is presumed to be the source of the Greek word gaia (earth, not heaven; land, not sea; a land, country, soil).In Greek mythology, Gaia was a goddess (‘Mother Earth’), the spouse of Uranus and the mother of the Titans.

The word-forming element geo- (earth, the Earth) comes from Gaia. Geo forms part of numerous words—geode, geodesic, geography, geometry, George (geo [earth] + ergon [work] = earth worker or, farmer), geophysics, and so on. The word-forming element -logy means discourse, doctrine, theory, science. In brief, geo + logy (Latin geologia) = the study of the earth.

The word geology (the science of the past and present condition of the Earth’s crust) came to English in 1795 from Latin geologia. Charles Darwin used the word geologize as a verb.

The word geologist is also from 1795. Other forms of the word geologist were geologer (1822) and geologian (1837); however, these words have not survived in common use.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on December 01, 2020 22:29

November 27, 2020

Instinct

Have you ever felt prodded or poked to do something? What might it mean to trust your instincts?

Have you ever felt prodded or poked to do something? What might it mean to trust your instincts?The word instinct comes from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root steig (to prick, stick, pierce) and Latin stinguere (to prick, to goad). A goad is a pointed rod or stick urged to urge on an animal; e.g., a cattle goad. The verb ‘to goad’ means to incite or rouse or urge on.

The Latin prefix in- (into, in, on, upon) + stinguere = instinguere (to incite, to impel) from which comes Latin instinctus (instigation, impulse, inspiration). By the early 15th century, the word instinct, meaning a prompting, had come to English. This meaning of instinct is now obsolete.

The use of instinct, meaning an animal’s faculty of intuitive perception, is from the mid-15th century (Does this mean that people who lived and worked with animals at that time sense that an animal might have intuitions?!).

By the 1560s, instinct was used to mean a natural tendency in an animal; for example, why do birds fly south for the winter? Instinct was (and is) the usual answer. Instinct was thought to be blind; that is, animals don’t consciously ‘trust their instincts’. Current research related to animal intelligence illuminates much more subtle understandings of the workings of animal minds—have you ever spent time watching crows or ravens, let alone the family dog?

What about people? Do we have instincts? Are these instincts conscious or unconscious? What does it mean to ‘trust our instincts’?

What is the difference between instinct and intuition? Intuition would seem to be a subtle internal knowing (perhaps some insight or feeling that sneaks up and taps you on the shoulder): “I have a good feeling about this.” On the other hand, instinct would seem to be a gentle (or not so gentle) poke from an external or unconscious source: “That person gives me the creeps.”

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 27, 2020 18:17

November 23, 2020

Black

What can we say about the word black? the color black? What is the connection between the word black and the word dark?

What can we say about the word black? the color black? What is the connection between the word black and the word dark?To consider such questions, look at the difference between Old English blac (bright, shining) and Old English bloec (meaning absolutely dark but not black). These two words, seemingly opposite in meaning, come from the same Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bhel (to shine, to flash, to burn). From this PIE root emerge two branches of usage of the word black—one related to light, one related to dark.

On the one hand, the Online Etymological Dictionary states, “The same root [PIE bhel] produced the Old English [adjective] blac (bright, shining, glittering, pale); the connecting notions being perhaps, ‘fire’ (bright) and ‘burned’ (dark), or perhaps the absence of color.”

On the other hand, PIE bhel is also the root of Proto-Germanic blakaz (burned) which is the source of Old Norse blakkr (dark), Old High German (OHG) blah (black), Swedish black (ink), Dutch blaken (to burn), and Old English bloec (absolutely dark, absorbing all light).

So where does the English word black come from? Originally, the English word black has its origins in OHG which has two words for black: swartz (dull black) and blach (luminous black), both from PIE bhel (shining). Again, we see the theme of light and dark, this time in relation to the word black. At first, the Old English word for black was sweart from OHG swartz. However, Old English sweart evolved to become the word swarthy (a dark color or complexion).

And, as sweart became swarthy, the Old English word bloec, originally meaning dark and absorbing all light, evolved to become the word for the color black. Remember that bloec comes from Proto-Germanic words rooted in PIE bhel (to shine, to flash to burn). Yet again we see the theme of light and dark in relation to black.

To bring another perspective to this discussion of black, I quote, and paraphrase, from an article, “Paint it Black”, in The Economist magazine (7 Nov 20):

“The discovery in ancient Egypt, China and Rome that writing (and, later, printing) worked best when black was used on a white background gives black a special place in the pantheon of colours. But before the concoction in Europe of black ink from gall nuts (tumours that grow on trees where insects have laid eggs), real black was hard to conjure up. The early artists in France’s Lascaux caves drew crude animals and human figures with charcoal, which sometimes washed away. Most confected blacks, especially fabric dyes, produced a muddy purply-grey or brown at best.

It was only when black pigments—made from coal, lampblack or even burned ivory—were successfully mixed with gum arabic or linseed oil that it became possible to create the black gloss that many European artists came to love, artists such as Caravaggio (1571 – 1610) and Velaquez (1599 – 1660). Black became a colour of high fashion. Black was perceived not only in its own right, but an enlivener of other colours.

Today, the blackest black ever created is [called] Vantablack which is not so much a paint as a coating of ‘nanotubes’ which instead of reflecting light, trap it almost completely. A circle of Vantablack on the floor could be a rug-like coating or a bottomless hole—there is no way of telling.”

In sum, in terms of light (blac) and dark (bloec), it would seem that you can’t talk about black without talking of both light and dark. Seems like even our ancestors knew something about this dual quality of ‘black’.

References:

Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2020/11/07/for-centuries-the-colour-black-has-tested-artists-ingenuity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black

Published on November 23, 2020 21:56

November 21, 2020

Fun

When you think of fun, what comes to mind? What do you like to do for fun?

When you think of fun, what comes to mind? What do you like to do for fun?Where does a word like fun come from, anyway? Who makes up such a word?

-o-

I realize that talking about fun during current Covid19 restrictions and cancellations may not be a fun topic, given that these restrictions are on what many might consider fun things to do. I do not mean to minimize or trivialize the discomfort, fear, and uncertainty we feel at this time by turning my attention to fun.

Perhaps an exploration of the word fun can say something to us at this time. Bear with me as I think out loud about this.

-o-

The origins of the word fun are unknown. However, from what is known, a somewhat disturbing and yet pleasantly surprising story can be told. Trickery, silliness, stupidity, and insanity are involved.

The word fun first appears to English in the 1680s as a verb: to fun. At that time fun meant to cheat or to play a hoax on someone: “Let’s go out and fun old Thomas at cards tonight!”

A few years later, around 1700, fun meant a cheat or a trick. By 1727, fun meant a diversion, an amusement, or a mirthful sport. ‘To make fun of’ someone is from 1737. Maybe to make fun of someone was to cheat them or trick them; maybe not. “Don’t get mad. We were just trying to have some fun!”

This seems to be about as much as we now know about the origins of the word fun. Perhaps people were having too much fun to stop and think about the word and where it comes from.

Some suggest that the word fun may be a variation of medieval English fonnen (to befool, to make a fool of). Fonnen comes from the late 14th century word fonned (to be foolish, simple, deranged, insane; silly, unwise). In the early 14th century, the word fonne meant a fool or a stupid person.

Are we having fonne yet?!

How about this: Are you fond of anything? Or anyone? What do you have a fondness for? Fond, another late 14th century word, comes from fonned (foolish, deranged, silly… as just noted).

Have you ever watched your teenage daughter or son be ‘in love’ or be ‘fond’ of someone? The words deranged, insane, foolish, silly, unwise often come to mind! But don’t worry—the kids are just having fun!

By the 1570s, the word fond meant ‘foolishly tender’ or ‘to have strong affections for’ or ‘to dote upon’.

The verb doten (to dote), from around 1200, meant to behave irrationally, to do foolish things, to be or to become silly or deranged (like buying a bouquet of flowers for your lover, just because, for no reason). Doten also meant to be foolish or out of one’s mind or to be feeble-minded from age (that is, to be ‘in your dotage’).

By the late 15th century, the word dote had come to mean ‘to be infatuated’ or ‘to bestow excessive love’.

What does all this have to do with the word fun?

The word fun was hardly used, at least in public, in the 18th century. Given that the use of the word fun in the early part of that century meant to cheat, you weren’t likely to tell your friends you had ‘fun’ on the weekend any more than you’d tell your friends that you cheated at cards on the weekend. In addition, something ‘fun’ was considered trite, pious, or insincere, not to mention the earlier associations of the word fun with foolishness or silliness or craziness.

Nevertheless, as time passed the word fun gradually began to take on a more positive tone although you can still sense the darker side of the word fun in more recent expressions.

Funny (humorous) is from 1756.

Funny bone (the elbow end of the humerus where the ulnar nerve passes relatively unprotected) is from 1826. If you have ever banged your funny bone, you’ll know that this is not a funny experience!

A funnyman (a circus or stage clown) is from 1854.

Fun and games (mirthful carryings-on) is from 1906.

The distinction between ‘funny ha-ha’ (humorous) and ‘funny peculiar’ (strange, odd, causing perplexity) is from 1916.

Funny money (counterfeit money) is from 1938.

Funny farm (a mental hospital) is from 1962.

Again, what does all this have to do with the word fun?

Merriam-Webster tells us that fun now means that which provides amusement or pleasure, playful, boisterous action or speech; a mood for finding or making amusement, enjoyment; to indulge in banter or play.

What are we to make of this evolution in meaning? How did fun come to mean being happy or doing something carefree?

One suggestion is that more people now than in the past have the time and resources and opportunities to ‘have fun’. If you live in a time and place where you work hard from dawn until dusk and then die of disease or childbirth before you are 35, you may not find that ‘fun’ is at the top of your Hierarchy of Needs (thank you for this, Mr. Maslow).

Another suggestion is that we can put ourselves in situations where ‘fun’ is likely to happen. We can go to a party or a hockey game or downhill skiing or cycling or surfing or whatever. What’s fun for one person may not be fun for another person. Can sitting with a good book and glass of wine in a cozy nook with a good friend during a cold Covid evening be considered fun (or simply something pleasurable)?

However, even though we may put ourselves in such situations, we can not make fun happen. Try whomping up fun at a party and see how far you get; “Come on, we’re going to have fun now, no matter what!” Alcohol may be involved. Fun, perhaps by definition, is something out of the ordinary. Fun happens by surprise.

Perhaps when we are having fun, we are not in our minds. In fact, we may be out of our minds! We are in our bodies. The sensations generated by and in our body by some activity are what make us feel that this activity is fun or pleasurable.

So, what might it mean to ‘have fun’ during the current Covid19 pandemic?

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 21, 2020 21:57

November 15, 2020

Anniversary

Happy Work Anniversary!!

16 November 2020: the 50th anniversary of my walking into a classroom for the first time as a teacher.

Anniversary: from Latin annus (year) + versus (to turn); versus from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root wer (to turn). Latin anniversarius (returning annually). The word anniversary comes to English around 1200 meaning ‘year day’ or the annual return of a certain date in the year. At that time, the word anniversary was used mainly in reference to saints’ days.

An Old English word for anniversary was mynddaeg (mind-day). To mind, to pay attention.

In the fall of 1970 I happened to be in Winnipeg looking for a job, any job, to earn money so that I could go back to university the following year. I have no memory of how I ended up in a job interview at Red River Community College (now Red River College), an interview that consisted of two questions: Do you have a university degree? Are you willing to work in northern Manitoba for the winter? I answered yes to both. I was relieved not to have been asked about the subject of my degree.

I was told to report to the campus principal in Ashern who would outline for me what I was to teach. I took the bus to Ashern on the weekend before the start of classes and discovered that the school was three ATCO classroom trailers on the Manitoba Hydro parking lot. My accommodation for the winter was a room at the back of one of the trailers. Shortest commute I have ever had in my life. The principal lived up the road in Moosehorn. She said we could talk before classes started Monday morning.

At 9 a.m. on the 16 November 1970, I walked into a classroom for the first time as a teacher. I was the youngest person in the room. I had been hired by Red River Community College’s Extension Services to teach Adult Basic Education. The participants in my courses were seasonally unemployed workers (loggers, fishers, carpenters…) whom the government was paying to go back to school to get their Grade 10 and/or Grade 12 completion certificates.

I looked around the room and immediately knew two things. First, these guys (they were all men) were much like the guys I had worked with in Saskatchewan during my summer jobs to pay my way through university, jobs which included tree planting, truck driving, provincial park maintenance work, and various other forms of unskilled outdoor labour. I knew that I could not bullshit these guys. Second, having had no form of teacher training whatsoever, I knew I had to somehow act like a teacher. What to do?

I took off my jacket and hung it on the back of my chair, loosened my tie, rolled up my sleeves, and said, “Okay, let’s have some introductions and then get to work.” The principal had given me a binder with the course materials at 8.45 that morning when we met. All the participants had already been given these materials. I opened the binder (for the first time), turned to the Table of Contents, and proceeded to outline for the group (and for myself) what the course was going to be all about. That night, I learned an amazing amount about curriculum development and lesson planning. Over the next few months, I found that I loved teaching and working to make material like Grade 10 grammar interesting and relevant to these adult participants. Ever heard of the POS family?

Fifty years later I still love walking into a classroom or training room and working with the folks who have shown up. Although these days I am more likely to be the oldest person in the room.

Footnote: A year and a half later, I was sitting in a Red River College classroom in Winnipeg marking assignments. A beautiful young woman, a new teacher I’d seen in the halls, stopped at my open classroom door and asked if I was David Tickner. Even if I had not been David Tickner, I would have said Yes. She said, “I just finished teaching all winter in Ashern. Your former students asked me to come and say hello to you.” Three months later we were married.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

16 November 2020: the 50th anniversary of my walking into a classroom for the first time as a teacher.

Anniversary: from Latin annus (year) + versus (to turn); versus from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root wer (to turn). Latin anniversarius (returning annually). The word anniversary comes to English around 1200 meaning ‘year day’ or the annual return of a certain date in the year. At that time, the word anniversary was used mainly in reference to saints’ days.

An Old English word for anniversary was mynddaeg (mind-day). To mind, to pay attention.

In the fall of 1970 I happened to be in Winnipeg looking for a job, any job, to earn money so that I could go back to university the following year. I have no memory of how I ended up in a job interview at Red River Community College (now Red River College), an interview that consisted of two questions: Do you have a university degree? Are you willing to work in northern Manitoba for the winter? I answered yes to both. I was relieved not to have been asked about the subject of my degree.

I was told to report to the campus principal in Ashern who would outline for me what I was to teach. I took the bus to Ashern on the weekend before the start of classes and discovered that the school was three ATCO classroom trailers on the Manitoba Hydro parking lot. My accommodation for the winter was a room at the back of one of the trailers. Shortest commute I have ever had in my life. The principal lived up the road in Moosehorn. She said we could talk before classes started Monday morning.

At 9 a.m. on the 16 November 1970, I walked into a classroom for the first time as a teacher. I was the youngest person in the room. I had been hired by Red River Community College’s Extension Services to teach Adult Basic Education. The participants in my courses were seasonally unemployed workers (loggers, fishers, carpenters…) whom the government was paying to go back to school to get their Grade 10 and/or Grade 12 completion certificates.

I looked around the room and immediately knew two things. First, these guys (they were all men) were much like the guys I had worked with in Saskatchewan during my summer jobs to pay my way through university, jobs which included tree planting, truck driving, provincial park maintenance work, and various other forms of unskilled outdoor labour. I knew that I could not bullshit these guys. Second, having had no form of teacher training whatsoever, I knew I had to somehow act like a teacher. What to do?

I took off my jacket and hung it on the back of my chair, loosened my tie, rolled up my sleeves, and said, “Okay, let’s have some introductions and then get to work.” The principal had given me a binder with the course materials at 8.45 that morning when we met. All the participants had already been given these materials. I opened the binder (for the first time), turned to the Table of Contents, and proceeded to outline for the group (and for myself) what the course was going to be all about. That night, I learned an amazing amount about curriculum development and lesson planning. Over the next few months, I found that I loved teaching and working to make material like Grade 10 grammar interesting and relevant to these adult participants. Ever heard of the POS family?

Fifty years later I still love walking into a classroom or training room and working with the folks who have shown up. Although these days I am more likely to be the oldest person in the room.

Footnote: A year and a half later, I was sitting in a Red River College classroom in Winnipeg marking assignments. A beautiful young woman, a new teacher I’d seen in the halls, stopped at my open classroom door and asked if I was David Tickner. Even if I had not been David Tickner, I would have said Yes. She said, “I just finished teaching all winter in Ashern. Your former students asked me to come and say hello to you.” Three months later we were married.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 15, 2020 21:24

November 12, 2020

Stevedore

The word stevedore comes from Spanish estibador (one who loads cargo, wool-packer) and Spanish estibar (to stow cargo). Both words come from Latin stipare (to pack down, to press).

Stevedore, from 1828, was first seen in English in 1788 as stowadore.

My paternal grandfather, Frank Tickner, was a stevedore who worked at the Teddington Locks on the River Thames. Teddington is a suburb west of London where cargo from deep draft vessels is transferred to smaller vessels heading farther up the Thames. Frank married my grandmother, Edith, a ‘downstairs maid’ who worked at a ‘big house’. They emigrated to Canada in 1906.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Stevedore, from 1828, was first seen in English in 1788 as stowadore.

My paternal grandfather, Frank Tickner, was a stevedore who worked at the Teddington Locks on the River Thames. Teddington is a suburb west of London where cargo from deep draft vessels is transferred to smaller vessels heading farther up the Thames. Frank married my grandmother, Edith, a ‘downstairs maid’ who worked at a ‘big house’. They emigrated to Canada in 1906.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 12, 2020 20:04

November 9, 2020

Remembrance Day

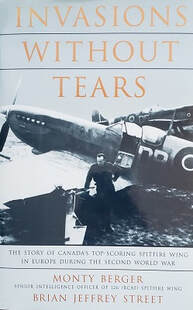

In memory of my grandfather, John Cameron, 16th Canadian Scottish, who was wounded in action at Vimy Ridge, 9 April 1917. In memory of my father, Sid Tickner, who served in the RCAF 411 Squadron and was part of the D-Day invasion, 6 June 1944. They are the men in the photographs.

In memory of my grandfather, John Cameron, 16th Canadian Scottish, who was wounded in action at Vimy Ridge, 9 April 1917. In memory of my father, Sid Tickner, who served in the RCAF 411 Squadron and was part of the D-Day invasion, 6 June 1944. They are the men in the photographs. The word remember almost remembers itself as it evolves from language to language over time.

The word remember combines Latin re (again, once more) + memorari = rememorari (to recall, to bring to mind, to remember). In the mid-14th century the word remembren (to keep something or someone in mind, to retain in memory) comes to English, and later the word remember.

The word remembrance has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root (s)mer (to remember).

PIE (s)mer is the root of many words related to remembrance and memory in many ancient languages; e.g., Sanskrit smarati (remembers); Greek merimna (care, thought); Latin memoria (memory, remembrance), memor (mindful, remembering), memorari (to be mindful of); Old Norse Mimir (the name of the giant who guards the Well of Wisdom), Dutch mijmeren (to ponder), Old English murnan (to mourn, remember sorrowfully).

Why has the word remembrance changed so little over time? Memorials and commemorations re-call and re-mind us that there is always something or someone to remember. To remember is to be re-minded or re-mindful of that about which we care and for which we are grateful.

See my article in The Walrus magazine: https://thewalrus.ca/the-war-carved-i...

References:

Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 09, 2020 11:28