David Tickner's Blog, page 34

March 13, 2021

Fruition

How many words do you know that end in -ion: meaning, the state or condition of something? For example, the word station means the state of being static or standing or stopped; information is the state or condition of being informed or informing; medication is the state or condition of a medical treatment; and so on.

How many words do you know that end in -ion: meaning, the state or condition of something? For example, the word station means the state of being static or standing or stopped; information is the state or condition of being informed or informing; medication is the state or condition of a medical treatment; and so on.So, what is fruition the state or condition of? Does this mean the state or condition of being fruit or like fruit? Hmmm….

The word fruition has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bhrug (to enjoy) and Latin frui (to use, to enjoy). Fruition has nothing to do with fruit unless, of course, you enjoy eating fruit.

Fruition (the act of enjoying) comes to English in the early 15th century from Old French fruition and Latin fruitionem (enjoyment).

The verb ‘to rejoice’ came to English around 1300 and, at that time, meant to enjoy the possession of something or to have the fruition (i.e., the enjoyment) of something. The word rejoice, meaning ‘full of joy’, is from the late 14th century.

PIE bhrug is also the source of many words related to agricultural or food products. Having enough good food in ancient times would certainly have been a source of joy and enjoyment. Such words include, for example, fructify, fructose, fruit, fruitful. Words, perhaps related to lack of food or enjoyment, include defunct, frugal, perfunctory.

So, consider eating an apple and rejoicing in its pleasure. Be filled with fruition.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on March 13, 2021 14:47

March 10, 2021

Competenc/y

Has anyone ever complimented you by saying, “You’re in fine feather today”, meaning that you did well or that you look good or that you are competent at what you do? Did you know that the words feather and competent have the same origins?!

Has anyone ever complimented you by saying, “You’re in fine feather today”, meaning that you did well or that you look good or that you are competent at what you do? Did you know that the words feather and competent have the same origins?!Both words originate in PIE pet (to fall or to fly). This word came to Greek as pteron meaning wing and passed to German as feder, to medieval English as fether, and to English as feather.

Also, Greek pteron (wing) is the source of Latin petere which means to fall, to rush at, or to desire. When we desire something enough to rush at it together, we competere; i.e., Latin com (together) + petere. Latin competere means to be qualified in order to strive together for something. Competere is the root of the words compete and competition.

From competere comes Latin competentia (a meeting or an agreement), French competence, and the English words competency and competence (from 1596 and 1632, respectively).

In Competency-Based Education (CBE) or training, a competency is described as a discrete skill or piece of knowledge or a certain attitude that a student will achieve by the end of a course or program. A CBE course or program comprises several discrete and distinct competencies. In some places, students are evaluated and graded on a competency by competency basis. At graduation, a student has come to ‘possess’ these competencies.

An advantage of CBE approaches is that a subject can be broken down into manageable units for teaching and learning; e.g., to enable individualized and/or online learning. A disadvantage is that one can become lost in the details; particularly when more and more information is now easily accessible in most subjects from a variety of sources. A reaction to this analytic CBE approach can be seen in the documenting of curriculum using Learning Outcomes which attempts to provide a synthesis or summary of the broad curriculum purposes contained in the competencies.

Such talk of competencies and outcomes and the debates over what they are and how and why they are to be used delight curriculum developers everywhere and arouse our passions. At one level, such debates are just interesting and stimulating. At another level, such debates reflect how much a curriculum reflects and shapes the values of community and society. However such discussion is beyond the scope of this piece of etymology.

Let us not forget, though, that the words competence and compete originally meant working together at something. And let us not forget the sense of desire which resides in the old Latin petere. That is, our competence is not just something we possess, but rather it continually emerges from our desire, our willingness to go after something. And even to go after it together.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on March 10, 2021 17:14

March 7, 2021

Farrier

The word farrier is related to ancient words meaning strong, powerful, vigorous, and holy.

The word farrier is related to ancient words meaning strong, powerful, vigorous, and holy.The word farrier comes to English from Latin ferrum (iron), a word of unknown origin, possibly from an ancient Semitic or Etruscan language. Related terms include Latin ferro (e.g., ferro-cement) and ferric (something pertaining to or extracted from iron) from 1799. Ferrous (something pertaining to or containing iron), from 1865, comes from Latin ferreus (made of iron) and Latin ferrum.

The Ferris Wheel is from American English, 1893. Could it be said that a farrier is someone who makes and repairs ferris wheels? Probably not.

In 12th century English, a ferrer or ferrour was an ironsmith. The surnames Farrar and Farrer are two forms, among others, of a surname from that time meaning ironsmith or ironworker or blacksmith. Ferrier, meaning one who shoes horses, comes to English in the 1560s from French ferrier (blacksmith) and Latin ferrarius (blacksmith), from Latin ferrum.

Today, words for iron which are related to science and technology come from Latin ferrum. The chemical symbol for iron on the Periodic Table of the Elements is Fe (from ferrum).

So, farrier, ferro, farric, and farrous all come from ferrum, the Latin word for iron. But, where does the English word iron come from?

The English word iron has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root eis (strong) and PIE is-(e)ro- (powerful, holy). PIE is-(e)ro- is the source of Greek ieros (strong), Sanskrit isirah (vigorous, strong), Proto-Germanic isarn, and Celtic isarnon.

Proto-Germanic isarn is the source of Old Saxon isarn, Old Norse isarn, Middle Dutch iser, Old High German isarn, and German Eisen. In addition, Celtic isarnon is the source of Old Irish iarn and Welsh haiarn. From these Germanic and Celtic words come Old English iren, Middle English iren, yron, and English iron.

In brief, paradoxically, even though ferrum originally meant iron, today ferrum and related words are used primarily in a scientific rather than an everyday sense. In contrast, PIE eis, which originally meant strong, powerful, holy is now the source of the now everyday word iron.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on March 07, 2021 12:50

March 4, 2021

Grammar

In recognition of 4 March: Grammar Day!

Grammar is a word with origins related to magic and glamour—something I wish I’d known when I learned grammar in elementary school. Where was Harry Potter when you needed him?

The word grammar comes from Latin grammatike (tekhne)—the art of letters, referring to the study of language and literature. In the medieval period, the word grammar was also used in reference to magic incantations, spells, and mumbo-jumbo.

In the early 14th century, the English words gramarye and grammar both meant learning and erudition. However, gramarye took on connotations of magic and enchantment (have you ever asked a child, “What’s the magic word?”). A gramare or gramaire was a book of conjuring or magic.

[An aside: as a twelve-year old in a Grade 8 grammar class, words like nouns, verbs, adjective, adverbs were understandable to me, but words like accusative, appositive, collocation, ellipsis, modal, passive infinitive, subjunctive did begin to seem a bit like mumbo-jumbo. And irony of ironies—my first teaching position involved teaching Grade 10 grammar to an Adult Basic Education class in rural Manitoba. As the youngest person in the room, I quickly realized that I would not survive if I was just a clone of my own boring Grade 8 grammar teacher.]

Anyway, the word grammar (Latin grammar, the rules of Latin) came to English in the late 14th century. By the 16th century, grammar was used in reference to the rules of the English (and any) language to which speakers and writers must conform.

The word glamour comes to English in 1720 from the Scottish word gramarye (magic, enchantment; from books related to occult learning). Glamour as a sense of magical beauty or alluring charm is from 1840. Glamour as a quality of Hollywood-style attractiveness and high-fashion is from 1939. In this context, I cannot help but think of cosmetics as a form of grammar for the face (cosmetic, from Greek kosmos = order, the opposite of chaos; cosmetics—ways to bring order to the chaos of a face). But I digress. Again.

The term grammar school (a school for learning Latin) is from the late 14th century. A grammarian (late 14th century) is a learned person (or magician) who works and writes in Latin. Grammar as a subject was introduced into the US school system in 1842. The surname Grammer (e.g., the American actor Kelsey Grammer) is from the late 12th century.

And, finally, the word grimoire (1849), a magician’s manual for invoking demons, is from Old French grimoire and grammaire (incantation, grammar).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Grammar is a word with origins related to magic and glamour—something I wish I’d known when I learned grammar in elementary school. Where was Harry Potter when you needed him?

The word grammar comes from Latin grammatike (tekhne)—the art of letters, referring to the study of language and literature. In the medieval period, the word grammar was also used in reference to magic incantations, spells, and mumbo-jumbo.

In the early 14th century, the English words gramarye and grammar both meant learning and erudition. However, gramarye took on connotations of magic and enchantment (have you ever asked a child, “What’s the magic word?”). A gramare or gramaire was a book of conjuring or magic.

[An aside: as a twelve-year old in a Grade 8 grammar class, words like nouns, verbs, adjective, adverbs were understandable to me, but words like accusative, appositive, collocation, ellipsis, modal, passive infinitive, subjunctive did begin to seem a bit like mumbo-jumbo. And irony of ironies—my first teaching position involved teaching Grade 10 grammar to an Adult Basic Education class in rural Manitoba. As the youngest person in the room, I quickly realized that I would not survive if I was just a clone of my own boring Grade 8 grammar teacher.]

Anyway, the word grammar (Latin grammar, the rules of Latin) came to English in the late 14th century. By the 16th century, grammar was used in reference to the rules of the English (and any) language to which speakers and writers must conform.

The word glamour comes to English in 1720 from the Scottish word gramarye (magic, enchantment; from books related to occult learning). Glamour as a sense of magical beauty or alluring charm is from 1840. Glamour as a quality of Hollywood-style attractiveness and high-fashion is from 1939. In this context, I cannot help but think of cosmetics as a form of grammar for the face (cosmetic, from Greek kosmos = order, the opposite of chaos; cosmetics—ways to bring order to the chaos of a face). But I digress. Again.

The term grammar school (a school for learning Latin) is from the late 14th century. A grammarian (late 14th century) is a learned person (or magician) who works and writes in Latin. Grammar as a subject was introduced into the US school system in 1842. The surname Grammer (e.g., the American actor Kelsey Grammer) is from the late 12th century.

And, finally, the word grimoire (1849), a magician’s manual for invoking demons, is from Old French grimoire and grammaire (incantation, grammar).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on March 04, 2021 08:29

March 1, 2021

Name

In recognition of 1 March: “Fun Facts About Names Day”!

“What is your name?” “My name is…”

“Tuhada nama ki hai?” “Mera nama … hai.”

“Comment vous appellez vous?” “Je m’appelle…”

How often have we used such words and phrases? Often these are the first words learned in a conversational language course. Or when we meet a child.

Or, “What’s the name of the street where you live?” or “What’s the name of that ingredient that has the sweet taste?” or “What’s the name of that thingamajig?” or “What’s her name again?” Have you ever been called on the carpet for calling someone names on the playground (or in the office or classroom, for that matter)? Names can contain emotion and power. “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me” – Really?!

Names are everywhere.

The word name in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language family has just about always been the word name. The word name comes from Old English nama and is related to Gothic namo, Old Norse nafn, Dutch naam, German Name, Old High German namo, Frisian nama, Old Saxon namo—all from Proto-Germanic naman and, before that, from PIE no-men (name); also the source of the Sanskrit word naama (name).

In the PIE language family, and presumably also in other language families, when we meet another person or discover some new food or object or animal or plant or whatever, we want to know the name by which it is called: “What do you call that?” Whether we have ordinary or profound experiences; we look for ways to name such experiences and ways to describe them.

PIE no-men came to Latin as nomen (name) from which is created the Latin and English word nomenclature: nomen = name + clatura (to call out); nomenclature = the naming of something or ‘calling something by name’.

And, of course, every personal name and family name comes from somewhere or something. My own name, as translated from its origins would be ‘Beloved banks of the twisting Itchen River’, but you can call me ‘David’ for short.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

“What is your name?” “My name is…”

“Tuhada nama ki hai?” “Mera nama … hai.”

“Comment vous appellez vous?” “Je m’appelle…”

How often have we used such words and phrases? Often these are the first words learned in a conversational language course. Or when we meet a child.

Or, “What’s the name of the street where you live?” or “What’s the name of that ingredient that has the sweet taste?” or “What’s the name of that thingamajig?” or “What’s her name again?” Have you ever been called on the carpet for calling someone names on the playground (or in the office or classroom, for that matter)? Names can contain emotion and power. “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me” – Really?!

Names are everywhere.

The word name in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language family has just about always been the word name. The word name comes from Old English nama and is related to Gothic namo, Old Norse nafn, Dutch naam, German Name, Old High German namo, Frisian nama, Old Saxon namo—all from Proto-Germanic naman and, before that, from PIE no-men (name); also the source of the Sanskrit word naama (name).

In the PIE language family, and presumably also in other language families, when we meet another person or discover some new food or object or animal or plant or whatever, we want to know the name by which it is called: “What do you call that?” Whether we have ordinary or profound experiences; we look for ways to name such experiences and ways to describe them.

PIE no-men came to Latin as nomen (name) from which is created the Latin and English word nomenclature: nomen = name + clatura (to call out); nomenclature = the naming of something or ‘calling something by name’.

And, of course, every personal name and family name comes from somewhere or something. My own name, as translated from its origins would be ‘Beloved banks of the twisting Itchen River’, but you can call me ‘David’ for short.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on March 01, 2021 08:05

February 27, 2021

Assassin; Hashish?

What is the connection between the word assassin and the word hashish? Is there a connection? It is commonly thought that the word assassin comes from the hashish that a sect of medieval Islamic assassins pumped themselves up with before heading out on a mission.

Hashish

The word hashish comes relatively unchanged to English in the 1590s from Arabic hashishin (powdered hemp, hemp), a word generally related to herbage, dry herbs, rough grass, and hay.

Assassin

The word assassin comes to English from medieval French assissini and medieval Italian assassini in the 1530s from Arabic hashishin, a derogatory Arabic nickname for the fanatical Nizari sect living in the mountains of Lebanon between 1090 and 1275. Hashishin is the plural of hashishiyy (hashish).

In contrast, the Nizari sect described themselves with the term Asasiyyan, from Arabic asas (principle). For the Nizari, Asasiyyan did not mean assassin, but rather ‘people of principle’.

Originally referring to the methods of political control exercised by the Asasiyyan, the term ‘assassin’ is now in several languages describing similar activities anywhere. However, in spite of the derogatory nickname given by fellow Arabs, there is apparently no evidence that they used hashish to intoxicate themselves—likely an embellishment by later Western writers.

Assassin and/or Hashish?

So, why was hashish used as a nickname for people who went around assassinating other people? Apparently, the Arabic words asasiyyun and hashishin sound very similar; perhaps, they could be considered homophones (words that sound the same, but are spelled differently and have different meanings; e.g., such as English homophones like idle/idol, steal/steel).

These two Arabic words were carried to Western Europe by soldiers, traders, and others. Over time, the similarities in their sound and meaning intertwined as they became part of Western European languages. And so the name assassin in English is derived from the derogatory nickname rather than from the name the Nizari gave to themselves.

There are similar cases in Western Europe as fringe or unpopular groups emerge. For example, the words Quaker and Jesuit were originally derogatory terms for members of, respectively, the Religious Society of Friends and the Society of Jesus (Jesuit is still considered derogatory in some contexts; e.g., one definition of Jesuit in the current Miriam-Webster Dictionary is “one given to intrique or equivocation”).

Such examples may reflect situations in which the emotion or affect attached to a word is what makes it stick in the language rather than the word’s more rational or theoretical meaning. Perhaps for this reason, the derogatory ‘hashashin’ stuck in people’s minds more than the descriptive ‘asasiyyun’.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_Assassins

Hashish

The word hashish comes relatively unchanged to English in the 1590s from Arabic hashishin (powdered hemp, hemp), a word generally related to herbage, dry herbs, rough grass, and hay.

Assassin

The word assassin comes to English from medieval French assissini and medieval Italian assassini in the 1530s from Arabic hashishin, a derogatory Arabic nickname for the fanatical Nizari sect living in the mountains of Lebanon between 1090 and 1275. Hashishin is the plural of hashishiyy (hashish).

In contrast, the Nizari sect described themselves with the term Asasiyyan, from Arabic asas (principle). For the Nizari, Asasiyyan did not mean assassin, but rather ‘people of principle’.

Originally referring to the methods of political control exercised by the Asasiyyan, the term ‘assassin’ is now in several languages describing similar activities anywhere. However, in spite of the derogatory nickname given by fellow Arabs, there is apparently no evidence that they used hashish to intoxicate themselves—likely an embellishment by later Western writers.

Assassin and/or Hashish?

So, why was hashish used as a nickname for people who went around assassinating other people? Apparently, the Arabic words asasiyyun and hashishin sound very similar; perhaps, they could be considered homophones (words that sound the same, but are spelled differently and have different meanings; e.g., such as English homophones like idle/idol, steal/steel).

These two Arabic words were carried to Western Europe by soldiers, traders, and others. Over time, the similarities in their sound and meaning intertwined as they became part of Western European languages. And so the name assassin in English is derived from the derogatory nickname rather than from the name the Nizari gave to themselves.

There are similar cases in Western Europe as fringe or unpopular groups emerge. For example, the words Quaker and Jesuit were originally derogatory terms for members of, respectively, the Religious Society of Friends and the Society of Jesus (Jesuit is still considered derogatory in some contexts; e.g., one definition of Jesuit in the current Miriam-Webster Dictionary is “one given to intrique or equivocation”).

Such examples may reflect situations in which the emotion or affect attached to a word is what makes it stick in the language rather than the word’s more rational or theoretical meaning. Perhaps for this reason, the derogatory ‘hashashin’ stuck in people’s minds more than the descriptive ‘asasiyyun’.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_Assassins

Published on February 27, 2021 11:10

February 26, 2021

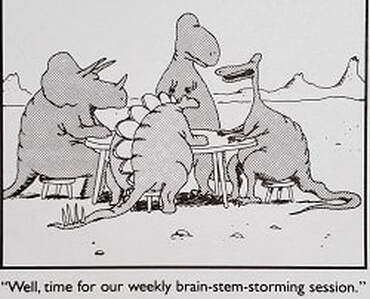

Brainstorm

Remember pre-Covid meetings or problem-solving or planning sessions which involved brainstorming? Flipcharts were posted, lists generated, ideas fly back and forth without judgment or discussion. Or maybe you’ve tried brainstorming via Zoom. Lots of information is (or can be) generated. But then what do you do with all this brainstormed information?

Remember pre-Covid meetings or problem-solving or planning sessions which involved brainstorming? Flipcharts were posted, lists generated, ideas fly back and forth without judgment or discussion. Or maybe you’ve tried brainstorming via Zoom. Lots of information is (or can be) generated. But then what do you do with all this brainstormed information?Brainstorming is usually just a first step of a problem-solving (or problem-setting) process. Consider the four steps of the BORC method: First, Brainstorm. Then Organize data into related clusters. Then Reflect (what’s going on in each cluster? What are underlying issues? What’s a tentative title for each cluster of data? Where are we headed with this discussion? What insights?). Finally, Consolidate: What implications? What actions? What next steps?

The word brainstorm, from 1861, originally meant “a fit of acute delirious mania or a sudden dethronement of reason and will; under stress of strong emotion; usually accompanied by manifestations of violence” (Brainstorm, Online Etymological Dictionary).

The use of the word brainstorm to mean a brilliant idea or mental excitement is from 1934. The July 1936 edition of the Popular Mechanics magazine described ‘brainstorm boys’ as “the daring and hair-trigger thinking of the men who handle the big news breaks and special programs” in the early days of radio broadcasting.

The use of brainstorm meaning to make a concerted attack on a problem involving the spontaneous generation of ideas is from 1947.

The word storm has its origins in PIE stur-mo (storm) and (s)twer (to turn, to whirl).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on February 26, 2021 16:57

February 23, 2021

Canvas

What do the words canvas and cannabis have in common? Does the word hemp come to mind?

What do the words canvas and cannabis have in common? Does the word hemp come to mind?The word hemp has its origins in the ancient Scythian and Thracian cultures. The Scythians, a nomadic people, lived in what is now, generally speaking, the Ukraine, southern Russia, Kazakhstan, and other smaller countries north of the Himalayas. The Thracians, generally speaking, lived in what is now the Balkans and surrounding areas.

The Scythian word hanapiz (hemp) was adopted without change into Proto-Germanic and evolved into other Germanic languages such as Old Saxon hanap, Old Norse hampr, Old High German hanaf, German Hanf, and Old English haenep—all meaning hemp. Hanapiz is also the source of Armenian kanap, Albanian kanep, Russian konoplja, Persian kanab, and Lithuanian kanapės--all meaning hemp. The word apparently did not change much over time or from place to place—when you’re trading such a valuable and useful product across cultures you want to make sure than everyone is on the same page with the name.

Scythian hanapiz migrated to Greek as kannabis (cannabis) and to Latin as cannibus sativa (hemp). The word hemp, meaning the fiber made from the plant, came to English around 1300. The word cannabis came to English in 1798 as the scientific name for the common hemp plant.

The use of hemp as a slang term for marijuana is from the 1940s. The word marijuana, by the way, came to English in 1918 from Mexican Spanish marihuana, a word of uncertain origin as the plant is not native to Mexico and any native sources for the word seem unlikely.

At last, we get to canvas (a sturdy cloth made from hemp or flax fiber), a word which came to English in the mid-14th century from Old French chanevaz (canvas; made of hemp, hempen), Latin cannapaceus (made of hemp), Latin cannabis, and Greek kannabis (hemp).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

PRESS RELEASE: David Tickner, May I Have A Word With You?

https://www.abbynews.com/entertainment/abbotsford-author-pens-book-about-origins-of-words-from-religion-and-spirituality/ 18 Feb 21

Published on February 23, 2021 08:13

February 20, 2021

Amaze, Amazing

Does a maze confound or amaze you? Is a maze a source of wonder or confusion? The words amaze and maze are related in Old English but before that the sources of the words are uncertain.

Does a maze confound or amaze you? Is a maze a source of wonder or confusion? The words amaze and maze are related in Old English but before that the sources of the words are uncertain.The word amaze comes from the Old English words amasod (amazed) and amasian (to confound, to confuse) from the Old English root maes. The Old English prefix a- added to maes when forming amasod and amasian suggests an intensity of amazement or confoundment or confusion. Old English maes may come from Norwegian mas (exhausting labour) or Swedish masa (to be slow or sluggish).

The verb ‘to amaze’ (to overwhelm or confound with sudden surprise or wonder) comes to English in the 1580s from Old English amasod and from the late 14th century word amased (stunned, dazed, bewildered). Earlier, in the 13th century, amased meant stupefied, irrational, foolish.

The adjective amazing, from the early 15th century, described something that stupefied or dumbfounded you. The noun amazement (mental stupefaction or the state of being astonished) is from the 1590s. By the 1590s, amazing also meant something dreadful.

However, by 1600 mazement meaning ‘overwhelming wonder’. By 1704, the word amazing also meant wonderful. What happened? The words amaze and amazement take an almost 1800 turn in meaning from around 1600—from stupefaction and dreadful to astonishment and wonder.

What might have prompted this relatively sudden change in what the word meant for people?

The word maze is also from Old English maes. Around the beginning of the 14th century, if something seemed delusional, bewildering, or a confusion of thought, it was called a maze. By the late 14th century, the word maze also meant a baffling network of paths or passages.

Maze or labyrinth? A maze has multiple entries, exits, paths, and dead ends. A labyrinth is like a maze except there is only one way in and one way out.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on February 20, 2021 12:44

February 18, 2021

Crony, Crone

Are you an old crony? Do you have any old cronies in your life?!

Are you an old crony? Do you have any old cronies in your life?!The word crony comes from Greek khronos (time) and khronios (long-lasting). The word crony, meaning an old familiar friend or an intimate companion, comes to English in the 1660s from Cambridge University student slang. For example, “We’ve been old friends for a long time… and we’re only just turning 30!”

Old crony does not necessarily mean old in terms of years but rather old in terms of long-lasting.

What about the word crone? The word crone means a feeble and withered old woman. The word came to English in the late 14th century and has its origins in Latin caronia (carrion) and caro (flesh). There is no connection to khronos. Is there a word for the male equivalent of a crone? I checked and could not find one (perhaps no surprise there). The closest I could find was the lists of words related to witches and warlocks, hags and ogres. Any ideas on this?

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on February 18, 2021 21:23