David Tickner's Blog, page 31

June 3, 2021

Goal

The word goal has uncertain origins. Perhaps people have not always been as interested in goals as we seem to be today. If there is no need for a word, it doesn’t get created.

The word goal has uncertain origins. Perhaps people have not always been as interested in goals as we seem to be today. If there is no need for a word, it doesn’t get created.The first appearance of the word goal, seen as gol, is from a poem of the early 14th century, and refers to a boundary or a limit. This word gol may come from Old English gal (obstacle, barrier) and gaelan (to hinder).

The use of the word goal as the end point of a race is from the 1530s, perhaps from the earlier use of gol as a boundary (or finish line?). Goal, in the sense of where, for example, you have to put the ball in order to score, is from the 1540s.

More generally, goal meaning the object of any effort is also from the 1540s. Interestingly, and perhaps not coincidentally, in Western Europe this is also the time of the Reformation and the beginning of modern thinking in relation to the individual and individual responsibility for actions (“What is my goal? What am I going to do about this?”).

In brief, the use of goal is first seen in relation to sports and games. The more general sense of a goal as the object of effort comes later.

What about the use of the term ‘goal’ in a curriculum? Given that the word curriculum has its origins in words related to running, perhaps it is not surprising that the early use of the word goal to mean a finish line for a race also came to mean the ‘finish line’ for a curriculum!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on June 03, 2021 13:33

June 2, 2021

Limner

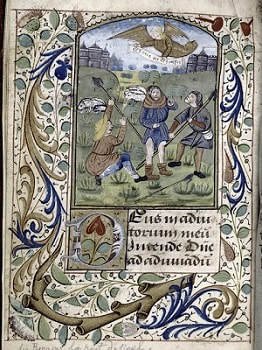

Do you know anyone who works as a limner? What kind of work is that, anyway? In brief, a limner is a watercolour artist who hand paints illustrations for books and manuscripts.

Do you know anyone who works as a limner? What kind of work is that, anyway? In brief, a limner is a watercolour artist who hand paints illustrations for books and manuscripts.The word limner has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root leuk (light, brightness), PIE leuk-smen (to shine), and Latin lucere (to shine) and lumen (radiant energy, light). From these sources come Latin luminare (illuminate, burnish) and 14th century Old French luminer (light up, illuminate).

By the early 15th century, the verb ‘to limn’ (to illuminate manuscripts) came to English from Middle English luminen and French enluminure (a painting with luminous colours); that is, to limn meant to provide illustrations that both illuminated and ‘enlightened’ the text of a manuscript (“While the English ‘to limn’ originally meant to create text or images in watercolours, it was also a general term for painting…” Evans, 2020).

A person who worked at limning was a lymner or a limner.

Technically speaking, during the medieval and Renaissance periods, limners were illustrators, not painters. Illustrators (or illuminators) of books and manuscripts usually worked in watercolour. Painters, on the other hand, created large paintings usually in oils.

In Renaissance Florence, book illuminators, painters in oils, stationers (book and paper sellers), and physicans[!] belonged to the Guild of Doctors and Apothecaries. Why? Because illuminators and painters bought their pigments from apothecaries. In London, limners and book writers had their own professional association, the Mistery of Stationers, which was separate from the Painters / Stainers Company who worked on cloth (e.g., canvas) and wood. In some places an illuminator or limner had to serve a two-year apprenticeship. Oil painters served a four-year apprenticeship.

The beginning of the end for the work of the limner was the development of the printing press in 1455 and the first printed books by Johannes Gutenberg. Nevertheless, in the 1590s, the term limn was used to mean ‘to portray or depict in watercolour’. However, by this time, the term ‘watercolourist’ rather than limner was appearing more and more in common use.

Other words associated with PIE leuk include elucidate, illustration, leukemia, lucid, Lucifer, luminary, lunacy, lunar, luster, lux, translucent.

References:

Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Evans, M. (2020). Renaissance watercolours: From Durer to Van Dyck. London: V&A, 14 – 16.

Published on June 02, 2021 20:28

May 31, 2021

Matrix

The red pill or the blue pill? Hmmm…

The red pill or the blue pill? Hmmm…The word matrix comes from a word which is almost unchanged since its origin—the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word mater (mother); in turn, the source of numerous words also meaning mother, notably Latin mater, Greek meter, Sanskrit matar, Old Irish mathir, Lithuanian mote, Proto-Germanic moder, Old Norse modir, Danish moder, Dutch moeder, German Mutter, and Old English modor. The word mother has been part of English since around 1200.

What does all this have to do with matrix? Latin mater (mother; also, source, womb) is the source of Latin matrix (a pregnant animal).

The word matrix (uterus, womb) came to English in the late 14th century from Old French matrice (womb, uterus) and Latin matrix. “The first clear use of the word matrix is in an English translation of the Gospel of St Luke (2:23) made in 1525 by William Tyndale” (Crystal, 2011, 95).

The many subsequent uses of the term matrix are from the notion of that which encloses or gives origin to something. The general sense of matrix as a place or medium in which something is developed is from the 1550s. The concept of matrix as a mould in which something is cast or shaped is from the 1620s. Matrix as an embedding or enclosing mass is from the 1640s.

In mathematics, a matrix is ‘a rectangular array of quantities (usually square)’ containing a set of components into which quantities can be set. In philosophy, a matrix as a logical sense of an ‘array of possible combinations of truth-values’ is attested by 1914.

In the 19th century, a matrix was seen as the elements that make up a network; e.g., a social or political network. In the 20th century, the term matrix management was used in the business world to mean the ways in which communication operates through a web of relationships.

Today, dentists, printers, and electronics engineers use the term matrix in different ways to describe aspects of their work. In the 1990s, the term matrix was used to describe the global network of electronic communication.

The movie with the red and blue pills, The Matrix, is from 1999.

Speaking etymologically about all this right now, rather than metaphorically, it would seem that the word matrix has come a long way from its origins in words for mother and womb.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Crystal, David. (2011). The story of English in 100 words. New York: Picador.

Published on May 31, 2021 17:54

May 28, 2021

Fairy

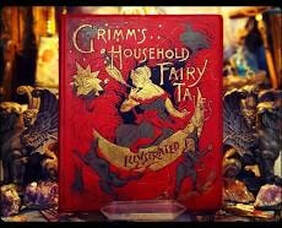

As a kid, you ever get money from the tooth fairy? Did you have a favorite fairy tale?

As a kid, you ever get money from the tooth fairy? Did you have a favorite fairy tale?The word fairy has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bha-(2)(to speak, tell, say) and Latin fatum (that which is ordained; destiny, fate), fae (fey; i.e., fated or doomed; prescient, able to tell the future), and fata (the Fates). In Roman mythology, the three Fates were Lachesis (the allotter), Clotho (the spinner), and Atropos (the unturnable, death). In brief, each person is fated to their lot in life (to being who you are), fated to the life which is spun out in front of them, and finally, fated to their death.

Hmmm… this seems like a long way from the ‘once upon a time’ fairy tales some of us grew up with—Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the Little Mermaid, Hansel and Gretel, Santa Claus and the elves at the North Pole, and so on.

The word fairie (fairy) came to English around 1300 meaning a place (not a creature); i.e., a fairie was the country or home of supernatural or legendary creatures; a fairyland. Fairie comes from 12th century Old French faerie (land of fairies, meeting of fairies; enchantment, magic, witchcraft, sorcery). The cute diminutive winged beings in children’s stories do not appear until the early 17th century.

The term ‘fairyland’, originally fairie, is from the 1580s.

The noun fairy-tale (an oral narrative centered on magical tests, quests, and transformations) is from 1749. The adjective fairy-tale (e.g., ‘a fairy-tale romance’) is from 1963.

By the way, an elf is traditionally defined as a mischievous young fairy.

Fairy tale or folk tale… what’s the difference? Generally speaking, folk tales are from ancient oral traditions with no known author. On the other hand, fairy tales, generally speaking, emerge from folk tales and are written down by recognized authors (e.g., the Grimm brothers).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 28, 2021 20:23

May 25, 2021

Purse or Handbag?

The earliest known purse was worn 5,000 years ago by a man, Otzi, the so-called Iceman, who is believed to have been murdered in the Otztal Alps between Austria and Italy. His mummified body was found by hikers in 1991.

The earliest known purse was worn 5,000 years ago by a man, Otzi, the so-called Iceman, who is believed to have been murdered in the Otztal Alps between Austria and Italy. His mummified body was found by hikers in 1991.The word purse has its origins in Greek byrsa (hide, leather), Latin bursa (hide), Old English pursa (little bag or pouch made of leather), and the pre-12th century word purse.

Why did the ‘b’ change to a ‘p’? Possibly because of the influence of early Norse settlers in what is now England—the Old Norse word for such a bag or purse was posi. However, the ‘b’ remains in words such as bursar (the treasurer of a college, from the 1580s; in Latin, a bursarius was a ‘purse carrier’) and bursary (the treasury of a monastery, from the 1690s).

By around 1300, the word purse referred to the royal treasury (at that time, purse also meant scrotum which gives new meaning to the term ‘family jewels’). In the 1640s, purse meant the sum of money collected as a prize in a race. By 1879, purse also meant a woman’s handbag.

What is the difference between a purse and a handbag? When I was a child, I noticed that my grandfather carried a small palm-sized leather pouch in which he carried coins. He called it his purse. This puzzled me because it looked nothing like what my mother called a purse. I thought that a purse was something a woman carried. Men carried wallets.

Generally speaking, until recently, in Britain, a purse (like my grandfather’s) was something carried by men. Women carried a handbag. On the other hand, in the US, only women carried a purse or a handbag (or simply a bag). A purse is smaller than a handbag (in a strange twist of language, a purse is carried by hand whereas a handbag is usually carried over the shoulder). In some places, the bag carried during the day is a handbag and a bag carried at night is a purse.

Only since the 1970s have men in North America began to carry bags (or purses) again. Where do you put your wallet and cell phone and sunglasses and coins and whatever else you need to carry around. All this stuff in your pants pockets looks weird. But what to call these bags? Manbags? Man purses? Murses? Fanny packs? Bro-sacks? Hmmm… keep working at it. The increasing use of ‘courier bag’ seems like a useful synonym for such a bag, if not for ‘purse’.

And, so, language continues to evolve.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 25, 2021 18:00

May 19, 2021

Gnomon

The word gnomon has travelled in several interesting directions from its origins in the PIE root gno (to know) and Greek gignoskein (to come to know) and gnomonikos (someone who is able examine and judge). In brief, in Greek, a gnomon was ‘one who knows’.

The word gnomon has travelled in several interesting directions from its origins in the PIE root gno (to know) and Greek gignoskein (to come to know) and gnomonikos (someone who is able examine and judge). In brief, in Greek, a gnomon was ‘one who knows’.How does a carpenter know if something is on the square? In ancient Greece, a carpenter’s rule or square was known as a gnomon. In Latin, a carpenter’s square was known as a norma, from gnomon.

How do you know the age of a horse or mule? By checking the gnomon of the animal; i.e., the teeth which indicate the age. “Their third and fourth teeth are called ‘gnomons’; that is ‘regulars’, because by them there is a tried rule to know their age” (Oxford English Dictionary, 1989).

How do you know what time it is? A gnomon is the vertical shaft or triangle that tells time by the shadow cast on your sundial. This use of gnomon comes to English in the 1540s from Latin and Greek gnomon.

What remains when you remove one of the corners of a parallelogram? A gnomon.

What about knowing or judging a person by the way they look? That is, as if judging a book by its cover? Such a judging of a person by their facial characteristics was known in the past as physiognomy—a now highly questionable approach to understanding human nature (i.e., judging or ‘knowing’ a person by their ‘physio’; i.e., by their ‘physical nature’.

What about the words ‘norm’ and ‘normal’? Yes, they are also rooted in Greek gnomon.

What about gnomes? Etymologically speaking, the words gnome and gnomon are cousins.

In brief, the word gnomon is related to many words related to knowing.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 19, 2021 09:28

May 16, 2021

Arithmetic, Mathematics

What is the difference between arithmetic and mathematics?

What is the difference between arithmetic and mathematics?Arithmetic

The word arithmetic has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root re (to reason, to count) and PIE erei-dhmo, the source of Greek arithmos (number, counting, amount), arithmetikos (of or for reckoning), and arithmetike tekhne (the science of counting).

The word arithmetic (the art of computation, the most elementary branch of mathematics) comes to English in the mid-13th century from 12th century Old French arsmetique.

Arithmomania, the compulsive desire to count objects and make calculations, is from 1884.

PIE re is the source of other words, notably ritual.1

Mathematics

The word mathematic has its origins in the PIE root mendh (to learn) and Greek manthanein (to learn), words which are the source of Greek mathema (science, knowledge, mathematical knowledge; a lesson; i.e., that which is learnt) and mathematikos (relating to mathematics, scientific, astronomical; pertaining to learning, disposed to learn).

In classical Greece, mathematics was one of three branches of Aristolelian theoretical science, along with philosophy (metaphysics) and physics.

The word mathematic comes to English in the late 14th century from Old French mathematique, Latin mathematica, and Greek mathematike tekhne (mathematical science).

By the 1580s, the word mathematics (the science of quantity; the abstract science which investigates the concepts of numerical and spatial relations) replaced the older term mathematic.

The word math, an American shortening of mathematics is from 1890. The British use maths, from 1911.

PIE mendh is also the origin of polymath (a person of encyclopedic learning).

[The word calculus, from 1660, a mathematical method devised by Sir Isaac Newton, comes from Latin calx (limestone, small stone) and Greek khalix (small pebble); i.e., a pebble used as a counter when calculating in ancient times.]

1 What’s the connection between arithmetic and ritual, aside from the fact that both contain ‘rit’? Arithmetic is unchanging: 2 + 2 always equals 4. Arithmetic is always the same everywhere at any time. On the other hand, even though a ritual is the same action over and over again, it can evolve and change over a period of time depending on social context.

Arithmetic and ritual are both transparent—when doing arithmetic or ritual we ‘look through’ an action to something meaningful beyond the action. For example, when we count money, we are not just thinking of numbers, we are thinking of money. Similarly, when we are singing the national anthem at the beginning of a sports event or having wine with a special dinner or responding with “I do” during a wedding ceremony, we participate in a ritual. Singing or drinking or responding is not the point. Rather, we ‘look through’ the ritual to the reason or reasons beyond the actual action in order to see a greater social or personal meaning.

Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fractal_art

Fractal art is a form of algorithmic art created by calculating fractal objects and representing the calculation results as still digital images, animations, and media. Fractal art developed from the mid-1980s onwards. It is a genre of computer art and digital art which are part of new media art. The mathematical beauty of fractals lies at the intersection of generative art and computer art. They combine to produce a type of abstract art.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 16, 2021 12:09

May 15, 2021

Understand, Overstand

In some ways, understand seems like such an odd word. When you understand something, what are you standing under?! Can you overstand something? I think I need to get to the bottom of this.

In some ways, understand seems like such an odd word. When you understand something, what are you standing under?! Can you overstand something? I think I need to get to the bottom of this.Under

Old English under and English under have always been ‘under’. Both words come from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ndher (under). In brief, in its origins, the word under is related not only to things being ‘under’ something but also among, and between each other.

Stand

Stand is also relatively unchanged from its origins in PIE sta (to stand, to make firm or to be firm). Among other things, Old English standan meant to stand firm, to abide, to be valid, to exist (to be present), stand up.

Understand

Originally, the Old English word understandan probably meant literally ‘to stand firm in the midst of’; and later meant to comprehend, to grasp the idea of, to ‘get it’. The related Greek word epistamai (to be close to) means, “I know how, I know it”; literally, “I stand upon”; i.e., “This is where I stand on the matter.”

In brief, to understand is to be interacting or engaged in something, to be close to something, or to be in the middle of something. Understanding, in such a context, is not just knowing something (i.e., knowing ‘what’ or ‘how’) but a deeper and more thorough knowing (i.e., a knowing ‘why’). It can be said that understanding is as much about ‘doing’ as about ‘knowing’.

The word under is also related in meaning to the word bottom, a word which in its origins is related to the 13th century words fundament and fundamental from Latin fundamentum (foundation, groundwork, support, beginning). In Medieval English, fundament also meant a person’s buttocks.

To understand is to get to the bottom of something.

Overstand??

Is there such a word? The word epistemology (the study and theory of the nature of knowledge) has its origins in the PIE root sta (to stand, to make firm), Greek episteme (knowledge, acquaintance with something), and Greek histasthai (to stand). Greek epi (over, near) + histasthai = epistasthai (to know how to do, to understand; literally, ‘to overstand’). The word epistemology was coined in 1856 by the Scottish philosopher James F. Ferrier (1808 – 1864).

Perhaps you have to ‘stand over’ or ‘stand back’ from something that you ‘understand’ in order to know what you know!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 15, 2021 12:07

May 12, 2021

Gnome

[image error] When you see a garden gnome in the corner of someone’s yard what do you think of? Do you think of words of wisdom or Renaissance medicine? I didn’t.

The word gnome has two completely different meanings and uses.

The word gnome, first seen in English in the 1570s, meant a short pithy statement of a general truth; i.e., an aphorism. Examples of such ‘gnomes’ include ‘Actions speak louder than words’, ‘He who hesitates is lost’, ‘The early bird gets the worm,’ ‘Less is more’, and so on.

This version of gnome came unchanged to English from Greek gnome (judgment, opinion; maxim, the opinion of wise men) and from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gno (to know)—the source of many words related to knowing and knowledge.

The second meaning of the word gnome (a dwarf-like earth-dwelling spirit) was first seen in English in 1712 and came from 16th century French gnome, Latin gnomus, and possibly from Greek genomos (earth-dweller).

This Latin word gnomus or gnomi, referring to these earth-dwelling spirits, was used by Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493 – 1541) in his study and writings on medicine. Hohenheim, better known as Paracelsus, was a well-known and influential Swiss physician during the Renaissance.

In his work, Paracelsus identified four elemental beings, each associated with one of the four elements of the natural order: water, fire, air, and earth. Nymphs were the elemental beings associated with water, salamanders with fire, sylphs with air, and gnomes with earth. Hmmmm…. “Take two salamanders and call me in the morning.”

In spite of these rather esoteric views (common for his time), today Paracelsus is noted for bringing science, particularly chemistry, to the practice of medicine. He is known for emphasizing the value of observation in combination with the received wisdom of his time.

This second meaning of gnome, the earth-dwelling spirit, is the one which is now most well-known. Gnomes were popular and well-known in the children’s literature of early 19th century England. The red-capped German and Swiss folklore garden figurines were first imported to England in the late 1860s from Germany. The term ‘garden gnome’ is from 1933.

I don’t know about you, but I think I’ll look at garden gnomes a little differently from now on.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

The word gnome has two completely different meanings and uses.

The word gnome, first seen in English in the 1570s, meant a short pithy statement of a general truth; i.e., an aphorism. Examples of such ‘gnomes’ include ‘Actions speak louder than words’, ‘He who hesitates is lost’, ‘The early bird gets the worm,’ ‘Less is more’, and so on.

This version of gnome came unchanged to English from Greek gnome (judgment, opinion; maxim, the opinion of wise men) and from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gno (to know)—the source of many words related to knowing and knowledge.

The second meaning of the word gnome (a dwarf-like earth-dwelling spirit) was first seen in English in 1712 and came from 16th century French gnome, Latin gnomus, and possibly from Greek genomos (earth-dweller).

This Latin word gnomus or gnomi, referring to these earth-dwelling spirits, was used by Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493 – 1541) in his study and writings on medicine. Hohenheim, better known as Paracelsus, was a well-known and influential Swiss physician during the Renaissance.

In his work, Paracelsus identified four elemental beings, each associated with one of the four elements of the natural order: water, fire, air, and earth. Nymphs were the elemental beings associated with water, salamanders with fire, sylphs with air, and gnomes with earth. Hmmmm…. “Take two salamanders and call me in the morning.”

In spite of these rather esoteric views (common for his time), today Paracelsus is noted for bringing science, particularly chemistry, to the practice of medicine. He is known for emphasizing the value of observation in combination with the received wisdom of his time.

This second meaning of gnome, the earth-dwelling spirit, is the one which is now most well-known. Gnomes were popular and well-known in the children’s literature of early 19th century England. The red-capped German and Swiss folklore garden figurines were first imported to England in the late 1860s from Germany. The term ‘garden gnome’ is from 1933.

I don’t know about you, but I think I’ll look at garden gnomes a little differently from now on.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 12, 2021 09:57

May 8, 2021

Thermos

The word thermos comes from Greek thermos (hot, warm). The end.

Well, okay, here’s a bit more. The first thermos bottle was built in 1892 by Sir James Dewar and was first manufactured commercially in Germany in 1904 by company called Thermos GmbH. The story goes that the company sponsored a contest to name the bottle and the winning name was, you guessed it, Thermos.

Sir James patented his design in 1904 and registered the Thermos trademark in Britain in 1907.

The word-forming element thermo- used in scientific and technical words also comes from Greek thermos which is originally from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gwher (to heat, to warm).

PIE gwher is also the sources of words such as brand (e.g., to brand cattle), brandy, brimstone, fornicate, furnace, hypothermia, and other words related to heat.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on May 08, 2021 12:02