David Tickner's Blog, page 28

October 3, 2021

Prussian Blue (don't lick your paintbrush!)

Until the l8th century, the Spanish conquerors of Mexico and Central America had a monopoly on the production of carmine red, a very expensive pigment made from the blood of millions of crushed cochineal insects.

Until the l8th century, the Spanish conquerors of Mexico and Central America had a monopoly on the production of carmine red, a very expensive pigment made from the blood of millions of crushed cochineal insects.Around 1704, while trying to make a synthetic carmine red, the Swiss pigment maker, Johann Jacob Diesbach, created Prussian blue. He had inadvertently added an oil-based alkali to a mixture of crushed cochineals and other chemicals. Instead of producing a red, he produced a blue of such beauty that “he thought he had discovered the original color of the sky” (Labatut, 19). Diesbach named the new pigment ‘Prussian blue’. Why? It seems he liked the Prussians. The technical name for Prussian blue is iron ferrocyanide. Cyan, by the way, means ‘dark blue’.

Prussian blue become so popular because of its color and its lower price that it all but replaced the much more expensive ultramarine (made from crushed lapis lazuli from Afghanistan).

In the mid-19th century, in the early days of photography (and photocopying), the first architectural ‘blueprints’ were created by dipping chemically treated drawings into a ferrocyanide solution which tinted the paper Prussian blue but left the drawing white (similar to a photographic negative).

In 1782, Carl Wilhelm Scheele inadvertently stirred a pot of Prussian blue with a spoon coated with sulfuric acid and created what he called Prussic acid; i.e., cyanide.

Scheele also created an emerald green pigment so dazzling and seductive it became Napoleon’s favorite color. Toys were painted with this emerald green. Thousands of European children became sick and many died from playing with these toys. Scheele had produced this emerald green by using arsenic (Labatut, 20).

In 1958, the American crayon company, Binney and Smith, phased out the color Prussian blue. Instead, they called the color Midnight Blue. Why? “Because teachers were complaining that schoolchildren couldn’t relate to Prussian history” (Finlay, 347).

https://harpers.org/archive/2021/10/tangled-up-in-blue-when-we-cease-to-understand-the-world-benjamin-labatut/

Finlay, Victoria. (2002). Colour. Travels through the paintbox. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 03, 2021 13:33

September 30, 2021

Fungible

I was reading an article in The Economist magazine recently about bitcoins and came across the term ‘non-fungible token’ (NFT) which I’ve heard repeatedly over the last little while. A few days ago, I read an online BBC news story about a popular internet meme, featuring a two-year old girl, that was sold as an NFT by her parents to a music company for about $100,000.

I was reading an article in The Economist magazine recently about bitcoins and came across the term ‘non-fungible token’ (NFT) which I’ve heard repeatedly over the last little while. A few days ago, I read an online BBC news story about a popular internet meme, featuring a two-year old girl, that was sold as an NFT by her parents to a music company for about $100,000.What the dickens does ‘non-fungible’ mean, I asked myself. And where does this word come from? (Other questions in relation to the meme could be asked, but I’ll restrain myself).

First, a ‘token’ is a unit of bitcoin cryptocurrency which is used similarly as a subway token—you buy a token (a coin-like object or card) and use it to gain entry to the subway. So then, what ‘non-fungible’ token?

The word fungible, a term from law and economics, means something that can be exchanged for something else of the same kind. For example: when you put a $50 bill into your savings account and later withdraw $50, you don’t expect to get exactly the same $50 bill as the one you deposited.

Or, a prairie farmer takes 10,000 bushels of wheat to the local great elevator and adds it to the wheat from other farmers. Someone who buys 10,000 bushels of this wheat gets 10,000 bushels of wheat regardless of whoever brought the wheat to the elevator. The farmers and the buyers are both dealing with wheat as a ‘fungible’ entity. The bill of sale is a ‘token’.

On the other hand, a watercolour painting is ‘non-fungible’. If I sold a painting for $500, the buyer would expect to get the actual painting—not just any watercolour painting worth $500.

Wikipedia tells us that a ‘non-fungible token’ (NFT) “certifies a digital asset to be unique and therefore not interchangeable. NFTs can be used to represent items such as photos, videos, audio, and other types of digital files” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-fungible_token).

The word fungible comes from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bhrug (to enjoy), PIE bhung (to be of use, to be used), and Latin fungi (to perform; not the same fungi which is the plural of fungus).

Fungible came to English in 1818 from Latin fungibilis as a legal term meaning ‘capable of being used in place of another; capable of being replaced’. The noun fungible is from 1765.

I can’t say that I know much more about bitcoin currency or NFTs than I did before, but I now know a bit more about fungibles and non-fungibles. And, as I was writing, my wife looked over my shoulder and assured me that, not to worry, I was quite ‘non-fungible’. Whew!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fungible

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/token

Published on September 30, 2021 12:33

September 26, 2021

Beech

The beech is a large forest hardwood tree noted for its smooth silvery bark and its mast (i.e., its small edible nuts) which accumulate on the forest floor and are often food for animals. That’s what the dictionary tells us.

The beech is a large forest hardwood tree noted for its smooth silvery bark and its mast (i.e., its small edible nuts) which accumulate on the forest floor and are often food for animals. That’s what the dictionary tells us.What the dictionary doesn’t tell us is that the word beech is related to items you likely have on your desk or in your briefcase right now.

First, the word beech has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bhago (beech tree), the source of Latin fagus (the scientific name for the beech tree). PIE bhago is the source of Proto-Germanic bokjon (beech), the source of Dutch beuk, Flemish boek, Old Norse bok, Old High German bouhha, German Buche, and Old English bece—all of which mean beech.

However, Proto-Germanic bokjon is also related to Proto-Germanic bokiz, the beechwood tablets on which runes were inscribed, the first systems of writing used by Old Norse and ancient Germanic peoples. From bokiz came German Buch (book) and Old English boc (book); in brief, a boc was made from the wood of a beech tree.

From bokiz to buch to boc to book—a book literally and figuratively comes from trees.

Similarly, the French word livre (book) and the English word library come from Latin librum (the inner bark of trees).

Perhaps it is not surprising to consider that over the centuries the tree has been a symbol of knowledge. Although this image might have to change if more and more people begin to get their knowledge from YouTube or social media!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 26, 2021 19:23

September 21, 2021

Autumn

What do you call the season between the end of summer and the beginning of winter? Fall? Autumn? Something else?

What do you call the season between the end of summer and the beginning of winter? Fall? Autumn? Something else?There are many words in the English language that begin with ‘au’ (from Greek autos, meaning self); for example, authentic, author, authority, autism, autocrat, autograph, automatic, autopsy, and so on. Autumn is not one of these words.

The words spring, summer, and winter all have origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE). However, there is no indication that autumn has PIE origins; in fact, the early origins of the word autumn are unknown. What is known is that the word autumpne came to English in the late 14th century from 13th century Old French autumpne and Latin autumnus—all words relating to the season. The word autumn appears in the 16th century.

What about the word ‘fall’? The traditional English name for the season was harvest. Another traditional term for the season was ‘fall of the leaf’ or simply ‘the fall’. By the 16th century, the word harvest was displaced by autumn; however, the word fall continued to be used.

The word fall, rather than autumn, is more commonly used in the United States than in England. Presumably early immigrants from England to America brought this more traditional word with them before the word autumn had become well-established.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 21, 2021 21:36

September 19, 2021

conservative, liberal, social

Note: alpha order, no capitals, no isms. Just etymology.

Note: alpha order, no capitals, no isms. Just etymology. conservative

The word conservative has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ser (to protect) and Latin com (together, with) + servare (to keep watch, maintain) = conservare (to keep, preserve, keep intact, guard). The word conservative came to English in the late 14th century as conservatyf (tending to preserve or protect, preservative, having the power to keep whole or safe) from Old French conservatif and from Latin.

Politically, the English word conservative reflects a reaction to the French Revolution of the 1790s. Conservative, as the name of a British political faction, first appears in the 1830s.

By the 1840s the word conservative, in a non-political sense, generally meant to be disposed to retain and maintain what is established and to be resistant or opposed to innovation and change.

Other words rooted in PIE ser include conservation, conserve, observance, preserve, reserve.

liberal

The word liberal has its origins in PIE leudh-ero (likely meaning, belonging to the people) and Latin liber (free, unrestricted, unimpeded; unbridled, unchecked, licentious) and liberalis (noble, gracious, generous; of freedom, as befitting a free person).

The word liberal came to English in the mid-14th century meaning generous, noble, free and, from the late 14th century, meaning selfless, magnanimous, admirable. From the early 15th century, the word liberal also meant extravagant and unrestrained in words and actions. By the 18th century, liberal meant free from prejudice, not bigoted or narrow.

Politically, the English word liberal meaning tending to favor individual personal political freedom and democracy is from around 1800. At that time, it was also used by opponents to refer to foreign lawlessness (e.g., the French Revolution). In the United States, from the early 19th century, the word liberal tends to mean favorable to government action to effect social change and an openness to new ideas and plans of reform.

In education, the term ‘liberal arts’ (i.e., the education necessary to be a free autonomous citizen) is from the late 14th century and refers to the traditional ‘core curriculum’ of universities of the 12th century—a curriculum comprised of the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy).

Other words related to liberal include deliverance, liberation, libertarian, libertine.

social

The word social has its origins in PIE sekw (to follow), Latin socius (companion, ally), and Latin socialis (of companionship, of allies; united, living with others; of marriage, conjugal).

By the early 15th century, the word social came to English meaning devoted to or related to home life. By the 1560s social meant living with others. Later, social came to mean characterized by friendliness or geniality (from the 1660s) and companionable (from the 1720s). Social, meaning ‘of pertaining to society as a natural condition of human life’, is from 1695.

Politically, the term socialist (1827) is from Comte de Saint-Simon, the founder of French socialism, a word that first appeared in 1837. Socialist and socialism were first used in the modern sense in French from 1835. In brief, socialism could be considered an outcome of the French Revolution; i.e., now that the Revolution is over and the monarchy is gone, how are we going to live and work together as a nation?

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 19, 2021 13:55

September 17, 2021

Mentor

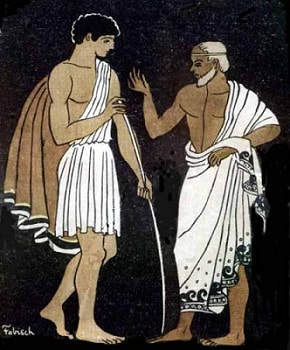

Have you ever been mentored? Are you a mentor? First, here’s a story about the origin of the word. Then some etymology and history of the word.

Have you ever been mentored? Are you a mentor? First, here’s a story about the origin of the word. Then some etymology and history of the word.The story

Once upon a time there was a king who sailed away with his army to fight in a foreign war leaving his wife and son at home to keep order in the kingdom. During the many years he was away, his wife was plagued by numerous suitors who had gambled that he was never coming back. They competed and conspired to marry her and take over the kingdom. But his clever wife never succumbed to their wiles. She trusted that the king would return.

After the war, no one knew where the king was or if he was even still alive. His son, Telemachus, a young man full of vim and vigor but more than a bit idealistic and naïve, became increasingly angry at his mother for tolerating these suitors and at his father for his absence.

Telemachus had a tutor named Mentor. We do not know much more about Mentor from this story other than that he was a loyal friend of the king and his family.

One day Mentor met Telemachus on the beach and suggested that Telemachus ‘borrow’ one of his father’s ships and with some of his friends go over to the next kingdom where they could join up with some of his father’s friends and try to track down his father.

But here’s the twist in the story. Mentor was actually the goddess Athena in disguise. As one version of the story says, ““for all the world with Mentor’s build and voice [she] urged him on with winging words” (The Odyssey, Book 2, lines 301 – 302). Not only does she urge him on, she also says, “the journey that stirs you now is not far off, not with the likes of me, your father’s friend and yours, to rig you a swift ship and be your shipmate too” (Lines 318 – 320). Athena was keeping an eye on Telemachus as a favour for her good friend, the king.

I’ll let you read the rest of the story for yourself. Sex and violence are involved.

What I find fascinating and intriguing about this story is that the goddess Athena, no slouch in the self-esteem department, chose to disguise herself as Mentor in order to support Telemachus.

According to Greek mythology, Athena, the daughter of Zeus and Metis, was born from the skull of her father, clad in full armour and shouting a war cry. She was considered the equal of her father in strength and wisdom. She was called the virgin goddess: “In all things,” she said, “my heart leans towards men, except in marriage.” She was also called the warrior goddess, using strategy, ambush, cunning and magic to achieve her purposes. She was against excess in daily life, teaching men to conquer their savagery, tame nature, and master the elements. She was the patron of weavers, horsemen, blacksmiths, shipbuilders, foresters, and carpenters. She invented the chariot. The city of Athens carries her name.

So why would Athena choose to disguise herself as an old man, as Mentor? Why might Mentor and Athena be embodied in one person as this story indicates? What is the ancient storyteller trying to tell us? What might this story tell us about mentor and mentoring? Any ideas?!

From what frame of reference would you begin to answer the question: Why did Athena disguise herself as Mentor??

The etymology

The word mentor has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) mon-eyo (advisor) from the PIE root men (to think). PIE mon-eyo is the source of Sanskrit man-tar (one who thinks), Hindi mantra (a chanted hymn or prayer), Greek mentos (intent, purpose, spirit, passion), Latin monitor (one who admonishes), and the word mind which came to English in the late 12th century.

The word mentor came to English in 1750 from Homer’s The Odyssey and means wise advisor, sage counsellor, and perhaps intimate friend. To be a mentor; i.e., ‘to mentor’ someone, is from 1888.

Two views of Mentor

Over the centuries, two views of the word mentor have evolved: a revision of the traditional view of Mentor based on The Odyssey and a more modern view of mentor as used in education and training.

The revisionist view suggests that rather than being a protective, guiding, and support figure, Mentor was “simply an old friend of King Ulysses who largely failed in his duties of keeping the King’s household intact” (Roberts, 1999). Other writers suggest that rather than Mentor, it was Penelope, Ulysses’ wife, who kept the kingdom and the household intact.

The more modern view of mentor derives from the work of the French writer and educator, Francois de Salignac de La Mothe-Fenelon (1651 – 1715), who was a tutor to the grandson and heir apparent of Louis XIV. Fenelon wrote a book, The Adventures of Telemachus, which became widely popular and continually reprinted during the 18th century, perhaps accounting for the fact that the word mentor comes to English at this time. In contrast to Homer’s Odyssey in which Mentor is more of a background figure, Fenelon’s book portrays Mentor in a much more prominent role as the wise advisor and sage counsellor. It is because of the popularity of Fenelon’s book that our current view of Mentor and mentoring is more a product of the Enlightenment than of ancient Greece!

References

Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Fagles, Robert (Trans.). (1996). The Odyssey. New York: Penguin, 93 – 106.

The Odyssey by Homer (who may have been one or several writers) composed two major works in the 8th century BCE--The Iliad and, its sequel, The Odyssey. The Iliad tells the story of the ancient Greeks and the Trojan War. One of the heroes of The Iliad is Odysseus (or Ulysses, as known in Latin), the king who is the father of Telemachus and the husband of clever and faithful Penelope. The Odyssey tells of Odysseus’s journey and eventual return home to his family after the war. I recommend the translations by Robert Fagles.

Hillman, J. (1996). The soul’s code: In search of character and calling. New York: Random House.

See pages 113 – 127, 163 – 165, et al for reflections on mentor and mentoring in terms of the importance of affect in the mentor / mentee relatlonship.

Robert, Andy. (1999). Homer’s Mentor: Duties fulfilled or misconstrued? History of Education Journal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242760920_Homer's_Mentor_Duties_Fulfilled_or_Misconstrued. Download, 17 Sept 2021.

Schon, Donald. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

See especially Schon’s description of the ‘joint experimentation’ style of coaching and communication between trainer and trainee, coach and learner, mentor and mentee.

Published on September 17, 2021 20:20

September 15, 2021

Forest

Forests are everywhere. But where does the word forest come from? There are several suggestions. None are certain.

Forests are everywhere. But where does the word forest come from? There are several suggestions. None are certain.Would you rather go for a walk in the forest or a walk in the woods? Why? The origins of the word forest include words related to foreign, park, and wood (or ‘the woods’) which may help to understand the difference.

The word forest came to English in the late 13th century meaning an extensive tree-covered district, especially one set aside for royal hunting and under protection of the king. The word forest, from Old French forest (forest, wood, woodland), likely comes from Latin forestem silvam (the outside woods).

The word forester came to English in the late 12th century as a surname. In the late 13th century, a forester was the officer in charge of a forest. Forester comes from Old French forestier (forest ranger, forest dweller; also, in early medieval times, forestier meant wild, rough, coarse, unsociable).

So far, this is all that is reasonably known for certain about the origin of the word forest. But let’s continue…

Latin forestem (the outside woods) may have come from either Old High German forst or Latin foris (outside). Latin foris, also the origin of the word foreign, appears to refer to land ‘outside of’ or ‘beyond’ such royal hunting lands. In this sense, a forest was a ‘foreign’ place.

Later, areas which had been designated as ‘forests’ or ‘royal game preserves’ became known as parks (e.g., game parks, from Latin parcus = a main or central fenced woodland). Areas designated for the use of military exercises or storage of military vehicles also became known as parks (hence, a car park or a parking lot). The surname Parker, from the mid-12th century, means a keeper of the park.

In brief, in English, a forest (or park) was a woodland under control or supervision whereas, in Latin, a foris (or forest) was a woodland beyond control or supervision.

Today, the word ‘woods’ tends to refer to relatively familiar places (e.g., wood lots, the back woods) whereas the word forest tends to refer to more unfamiliar places; for example, “Let’s go for a walk in the woods (or the park)” rather than “Let’s go for a hike in the forest.” In terms of canopy cover and density, woods tend to be more open; forests tend to be more enclosed.1

The noun forestry, meaning the privilege of a royal forest, is from the 1690s. Forestry meaning the science of managing forests is from 1859.

The verb ‘to reforest’ (to restore to a wooded condition, replant with forest trees) is from 1831.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

1 I can’t leave the word forest without reference to contemporary forestry research which suggests that a forest is not just a bunch of single trees but, rather, to over-simplify, a forest comprises a series of ‘clumps’ or clusters of trees, each of which emerges from a single integrated underground root and fungal system. In brief, each clump or cluster of trees seems to be one tree; i.e., perhaps a forestree?!

A pioneering researcher in this field is Suzanne Simard, a professor at UBC:

https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_simard_how_trees_talk_to_each_other?language=en

Also:

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 19 – 20.

Macfarlane, Robert. (2019). Underland. London: Penguin, 88 -91, 103 – 105.

Published on September 15, 2021 11:55

September 14, 2021

Bannock

The Online Etymological Dictionary suggests that Gaelic bannach (a cake), the source of the word bannock, is perhaps a loan-word from Latin panis, which in turn has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root pa (to feed, to protect). Another source suggests that Gaelic bannach is from Old Brittonic bannoc.

The Online Etymological Dictionary suggests that Gaelic bannach (a cake), the source of the word bannock, is perhaps a loan-word from Latin panis, which in turn has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root pa (to feed, to protect). Another source suggests that Gaelic bannach is from Old Brittonic bannoc.In brief, the word bannock (a thick flat cake or bread baked on the hearth or under ashes) comes from Gaelic bannach via Old English bannuc. The Online Etymological Dictionary also suggests that bannuc may be the source of the word bun.

David Crystal, the noted linguist, has observed that very few everyday Old English words have such a clear Celtic connection. Bannach is one of these words, along with brock, crag, wan, dun, and a dozen or so others (Crystal, 2013, 37).

Here’s a question: In pre-contact indigenous North American societies, was bannock a local food or was it a later import; e.g., from Scotland via the fur trade? There is no clear answer to this question. Some suggest a type of bannock (similar to corn bread) may have been made from North American sources such as maize or camas bulbs. Others disagree. I will leave this question to the experts for further research and discussion.

Other words from PIE pa include company (literally, ‘with bread’ or ‘sharing bread’!), food, forage, pabulum, pannier, pantry, pastor, pasture.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Crystal, David. (2013). The story of English in 100 words. New York: Picador.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_English_words_of_Brittonic_origin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bannock_(food)

Published on September 14, 2021 19:35

September 12, 2021

Peach

What does it mean to be impeached? Does this mean someone comes and takes away your peaches?! What’s the difference between peach and impeach?

What does it mean to be impeached? Does this mean someone comes and takes away your peaches?! What’s the difference between peach and impeach?In brief, the peach has its origins in ancient words for Persia. The peach tree, native to China, came to Europe via Persia and ancient Greece. The Greek phrase for peach, persikon malon (Persian apple), is from Persis, the Greek word for Persia. The Latin phrase for peach, from Greek, is malum persicum which also means Persian apple.

The word peche or peoche (peach; the fleshy fruit of the peach tree) came to English around 1400 from Old French pesche and Latin pesca, pessica, and persica, all variations of malum persicum. Old English also had a word for peach--persoe—which came directly from Latin.

For centuries, Persia has been the name given by Europeans to Iran, a traditional name by which Iranians now call their country. Historically, the dynasties of the ancient Persian Empire and Iran evolved and changed over the centuries in much the same way that China and its various dynasties evolved and changed over the centuries.

What is the connection between peach and impeach? There isn’t one. The word impeach has nothing in common with the word peach. Impeach comes from ancient words meaning to impede (i.e., putting your foot in the way of something). Impede comes from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ped (foot; e.g., pedestrian). Briefly, perhaps, to impeach, is to ‘put your foot down’.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 12, 2021 20:28

September 9, 2021

Sylvan

Did you ever wonder what Pennsylvania and Transylvania have in common? In brief, in both places, ‘sylvania’ refers to their forests.

Did you ever wonder what Pennsylvania and Transylvania have in common? In brief, in both places, ‘sylvania’ refers to their forests.Transylvania means ‘beyond the forest’. Pennsylvania is ‘William Penn’s forest’—named for William Penn (1621 – 1670), a British admiral who lent the English King Charles II money which in turn was repaid to his son in the form of land for a Quaker settlement in the American colonies.

The word sylvan (of the woods) came to English in the 1570s from French sylvain and Latin silvanus (pertaining to wood or forest). Originally, Latin silvanae referred to the goddesses of the forests, from Latin silva (woodland, forest, grove). The origin of silva is unknown.

The names Sylvia, Sylvester, and Silas are derived from Latin silva. The word silviculture refers to the art and science of managing, sustaining, and caring for the forests.1

Latin silva and silvaticus (of the woods, wild) are also the origin of the word savage which came to English in the mid-13th century via Old French sauvage (wild, untamed, strange). By the early 14th century savage mean animals or places that were wild, undomesticated, or untamed. By the early 15th century, the noun savage referred to a ‘wild person’ or to a person who lived in the wild.

The word savage, like the words heathen and pagan, originally referred to the places where people lived rather than to the people themselves. Unfortunately, such words have often been used rudely or disparagingly to describe the people not the place; in particular, those ‘other’ people who are not like ‘us’ (whichever ‘us’ to which you or I belong).

Silvanae or savage? Hmmm….

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

1 In case you are wondering, the Sylvania brand name for light bulbs is from the early 20th century when the fledgling company which produced the bulbs was based in Emporium, Pennsylvania—no apparent connection to forests!

Published on September 09, 2021 19:19