David Tickner's Blog, page 30

July 24, 2021

Patio

Do you have a patio where you live?

Do you have a patio where you live?Have you enjoyed a meal or a drink on the sidewalk patio of a restaurant lately and watched the cars and pedestrians go by? In its origins, a patio was a pasture where you could sit and watch the cows go by.

Patio is a Spanish word. One theory suggests that the origin of the Spanish word patio is Latin patere (to lie open). A second, more specific theory, suggests that the Spanish word patio is from Old Provencal patu, pati (untilled land, open land, communal pasture) from Latin pactum (agreement, contract, covenant; i.e., an agreement on the use of a piece of land).

In either case, the word patio (an inner courtyard open to the sky) came unchanged to English from Spanish patio and is first seen in 1818.

The term ‘patio furniture’ (known in Ireland as paddy o’furniture) is from newspaper advertisements in California in 1924. Patio, meaning a paved and enclosed terrace beside a building, is from 1941. The term ‘patio door’ is from 1973.

Patio or lawn? Or yard?

In its origins, the word lawn was a glade or open space in a forest (Middle English launde). Also, a lawn was a clearing or open space on the heath or other barren land (from Old French lande). The use of lawn to mean a grassy ground kept mowed and manicured is from 1733.

A thought: just as a ‘lawn’ seems an attempt to recreate a mowed and manicured English country garden in one’s yard, perhaps a ‘patio’ is an attempt to recreate something of the rural countryside in one’s yard… hmmmm. Yard, by the way, is related to the word garden (flower garden, vegetable garden, memorial garden, etc) and comes from old words meaning an ‘enclosed field’.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on July 24, 2021 14:44

July 17, 2021

Green

Painters: Do you mix your own greens or do you use tube-based greens? Or both? Why?

Painters: Do you mix your own greens or do you use tube-based greens? Or both? Why?When did green become a ‘color’ used by painters?

When the word green first came to English, it referred more to a ‘condition’ or to a ‘place’ than to a ‘color’. When the adjective green came to English around 1200, it meant a field or a meadow covered with grass or foliage. In the mid-13th century green referred to the skin or complexion of someone who was sick (“I shouldn’t have had so much to drink last night. I feel a little green around the gills”). By the early 14th century, the word green referred to unripe or immature fruit or vegetables and to someone youthful, immature, or inexperienced (e.g., a greenhorn). In the late 15th century, the ‘green’ was a piece of grassland in a village belonging to the community (i.e., the village green). By 1849, a green was where putting happened on a golf course.1

The word green has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ghre (to grow, to become green) and Proto-Germanic groni, the source of Old Saxon grani, Old Frisian grene, Old Norse groenn, Danish gron, Dutch groen, Old High German gruoni, German grun, and Northumbrian groene (green, the color of living plants), and Old English grene. The word for green has varied only slightly from language to language over the centuries.

Green. Grow. Grass. PIE ghre is not only the source of the word green but is also the source of the verb ‘to grow’ and the noun ‘grass’ (from PIE ghros, a young shoot, sprout; from PIE ghre).

Green, or grass-green, as the name of the color, came to English around 1300 from Old English graesgrene (literally, ‘the color of grass’; sort of like the term ‘sky blue’).

“Green is in many ways the most natural colour in the world… most of the world is green... Yet for artists it has long been a difficult colour to reproduce, and this most ‘organic’ of colours—the colour of grass and trees and fields—has in fact often been made traditionally from metal, or, to be more accurate, from the corrosion of metal” (Finlay, 294).

For example, the 14th century English word verdigris (from 13th century Old French verte de Grece; i.e., ‘green of Greece’) names a poisonous green or greenish-blue pigment made from the scrapings of corrosion from copper which has been exposed to air or to acetic acid. The green produced from this pigment is sometimes called Van Eyck Green, from its dramatic use by the 15th century Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck.

Other examples of sources for the color green include the right mix of fire, clay, and glaze to produce the greens of the ancient Chinese ‘celadon’ pottery, a green pigment first made from ground malachite by the ancient Egyptians, and Scheele’s Green (a combination of chlorine, oxygen, and arsenic) from the 1770s. (Note to self: Remember not to lick my paint brushes).

However, until the production of synthetic greens in the chemical laboratories of the 19th century, artists generally avoided using such expensive and dangerous products. Instead, they created greens by mixing variations of yellow and blue pigments.

1 Green used in railway signals (‘go ahead’) is from 1883. To give someone permission or to give them the ‘green light’ is from 1937. Green thumb in reference to gardening is from 1938. The term ‘green room’ (a place for actors to rest when not on stage) is from 1701. Green has been the color of environmentalism since 1971.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Finlay, Victoria. (2002). Colour. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Published on July 17, 2021 10:00

July 14, 2021

Pagan, Heathen

In ancient times, the words pagan and heathen were derogatory terms, used in the same way that words such as country bumpkin, country cousin, hayseed, hick, hillbilly, redneck, rube, yokel, and so on, are now used.

In ancient times, the words pagan and heathen were derogatory terms, used in the same way that words such as country bumpkin, country cousin, hayseed, hick, hillbilly, redneck, rube, yokel, and so on, are now used.Pagan

The word pagan came to English in the 14th century from Latin paganus (villager, rustic; civilian, non-combatant) and from Latin pagus (province, rural district). The word paganus was also derogatory Roman military slang for a civilian or an incompetent soldier.

The word paganus (pagan) was first used in a Christian context in the 4th century following the formal recognition of Christianity by the Roman Emperor Constantine. At that time, Christians were urban and literate. Pagan was used to describe people of the rural countryside who were not Christian or Jewish. The equivalent term in later Greek Christianity was hellene.

In brief, in its origins, pagan was not a word related to religion; it simply meant where you lived.

Pagan, as applied to modern pantheists and nature-worshippers, dates from 1908.

Heathen

In brief, heathen are people who live on the heath. The word heath has its origins in PIE kaito (forest, uncultivated land), Proto-Germanic haithiz (heath), and Old English haed (untilled land, tract of wasteland). Heathens were people who lived on such uncultivated land or on the poor soil wasteland of rural areas.

How did the word heathen change in meaning from ‘where you lived’ to ‘what you believed’ (or what you did not believe)?

The Online Etymological Dictionary suggests that the influence of Latin Christianity in 4th century Roman Britain can be seen in Old English haeden, a word from Old Norse haidinn (heathen). However, rather than simply meaning someone who lived on the heath, Old English haeden referred to anyone who did not acknowledge the God of the Bible. In particular, heathen referred to the non-Christian Danish invaders with whom the predominantly Christian Anglo-Saxons were fighting during this time and later periods. These ‘heathen’ were your enemies.

(https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=heathen).

In any case, the word heathen, meaning those who are not Christian or Jewish, appears in English before the 12th century. The term heathen no longer simply referred to where you lived.

In brief

During the early years of an urban and literate Christianity, the terms pagan and heathen were generally used to describe people in conservative rural areas who adhered to the old gods and to describe people who were not (yet) baptized. Only later, did these terms begin to be used in a derogatory manner when referring to people who were not Christian.

And, even though words like pagan and heathen are not commonly used anymore, don’t worry, there are still lots of other derogatory words you can use about people when you’re angry or fearful or upset about something.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on July 14, 2021 10:52

July 8, 2021

Book

The paper in books usually comes from trees. Not only that, the word ‘book’ also comes from trees.

The paper in books usually comes from trees. Not only that, the word ‘book’ also comes from trees.The word book has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bhago (beech tree), the source of Latin fagus which is the scientific name for the botanical genus of beech trees.

From PIE bhago evolved Proto-Germanic bokiz (beech) and modern German buche (beech) and buchstaben (a beech stick). Beech wood, because of its softness and ease of cutting, was most often used as a medium for the use of runes (i.e., any of several alphabets used by Germanic peoples from about the 3rd to the 13th centuries) which were carved into the wood. Perhaps it is not surprising that German Buch (book) comes from buche (beech tree).

The Old English word boc (book), from Proto-Germanic bokiz, originally meant any written document. Later, the word book came to mean a written work of many pages fastened together and bound.

From bokiz to Buch to boc to book—a book literally and figuratively comes from trees.

Similarly, the French word for book (livre) comes from Latin librum (the inner bark of trees) and from PIE lubh-ro (leaf, rind). The word library also comes from these sources.

Perhaps it is not surprising to consider the image of the tree has been used as a symbol of knowledge over the years. However, this image might have to change if more and more people begin to get their knowledge from YouTube and Wikipedia!

Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on July 08, 2021 11:00

July 1, 2021

Logs, Diaries, Journals

Log

Log Remember “Captain’s Log, Star Date 190421...”? And so began another episode of the famous TV series. What is a log, anyway? Ships have logs. Airplanes have logs. Truckers have logs. Truckers haul logs.

The origins of the word log are unknown, possibly from Old Norse lag (felled tree) from liggja (to lie); hence a log is a tree that lies on the ground. Also, there are possible connections with Proto-Indo-European (PIE) legh (to lay oneself down). From legh comes Greek lechos (bed) and lochos (lair), German liegen, and the Old English word licgan (to lie down).

In any case, in its origins the word log appears related to the action of ‘laying something down’. The word log, meaning a piece of a tree or a lump of wood, does not appear in English until the early 14th century.

So, what does all this have to do with a log; i.e., a logbook?

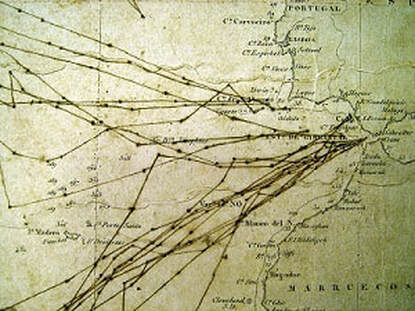

The term log or logbook comes from the early days of sailing and navigation. To measure a ship’s speed, a piece of wood (or log) weighted at one end was ‘laid down’ vertically in the water. The top end of the ‘log’ was attached to a long ‘log line’ knotted at regular intervals. Once the log was in the water, a sailor counted the knots as they played out in relation to the time. Hence the nautical term ‘knot’ as a measurement of speed. To keep a record of your travel, you would write down (i.e., lay down) the speed and other details in the logbook.

This use of the term ‘logbook’ is from the 1670s; the shorter term ‘log’ is from 1842. The sense of a log as any record of facts entered in order is from 1913. The verb ‘to log’ (to enter information into a logbook) is from 1823. To ‘log in’ to a computer (or to ‘log off) is from 1963.

If you are still wondering, there is no apparent common origin for log as the act of ‘laying down’ and a log as a ‘fallen tree’. The fact that a log is a tree that is lying down does not indicate or prove any etymological connection.

Diary

Diary comes from Latin diarium meaning the record of a daily allowance; i.e., a per diem. Diarium and per diem come from Latin dies (day) and dietas (diety, divinity, divine). The origin of these words is PIE deiwos (god) and dei (to gleam, to shine). From these roots, we also get Latin deus (god) and Sanskrit deva (god).

So, a diary is a book in which you record the shining moments of each day; e.g., how much of your allowance you spent for food or on gas for the car!

Journal

Like diary, journal has its roots in Latin dies (day) and diurnalis (daily), and in PIE dei. From these roots, we also have the words diurnal (happening each day) and nocturnal (happening each night). In pre-medieval France diurnalis became journal (daily). From France, journal came to medieval England as the word for a book containing the forms of worship for each day.

In contrast to a diary, a journal became a record of one’s ‘interior’ events, a record of one’s thoughts, feelings, and other reflective browsings.

In brief…

A log is a book for laying down facts and details and information. A diary is a book for highlights, lowlights, aha moments. A diary records what happened and first thoughts and feelings about what happened. A journal is a book for reflection and drawing insights, implications, and next steps from what happened.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on July 01, 2021 14:39

June 27, 2021

Provocative

Did you know that in the early 15th century a provocative was an aphrodisiac?

Did you know that in the early 15th century a provocative was an aphrodisiac?The words provocative and provocation have their origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root wekw (to speak) and Latin vox (voice) and vocare (to call). Latin pro (forth) + vocare = provocare (to call forth, to challenge).

Latin provocare is the source of the late 14th century English verb provoken (to provoke: in medicine, to induce sleep, vomiting, etc; and, to stimulate appetite). More generally at this time, provoken also meant to urge, incite, or stimulate to action. Today, ‘to provoke’ means to stir up a feeling or an action.

Provocative

In the early 15th century, the word provocative, from provocare, first appeared as a noun meaning an aphrodisiac. In the 1620s, a provocative was something that “served or tended to excite or stimulate sexual desire” (Online Etymological Dictionary); “Not tonight, dear, I’m feeling a little unprovoked.”

By the mid-15th century, the adjective provocative, from Latin provocativus (calling forth), was being used to describe that which elicits, provokes, excites, or stimulates.

Provocation

The noun provocation came to English about the same time as provocative; i.e., the early 15th century. The word provocation came from Latin provocationem (a calling forth, a summoning, a challenge; specifically, the act of exciting anger or vexation) and from provocare. Provocation, meaning anything that excites anger or that is a cause of resentment, is from 1716.

Some other related words include advocate, convocation, evoke, revoke, unequivocal, vocabulary, vocal, vocation, and vociferous. And, of course, voice.

Image: https://quietdisruptors.com/thoughtful-provocation/

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on June 27, 2021 12:34

June 23, 2021

Summer

Summer is one of those words, like father or mother or others close to heart and home, that has come to us almost unchanged since its origin thousands of years ago.

Summer is one of those words, like father or mother or others close to heart and home, that has come to us almost unchanged since its origin thousands of years ago.The word summer has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root sm (summer) which is the source of words such as Sanskrit sama (season), Avestan hama (in summer), Armenian amarn (summer), and Old Irish sam, Old Welsh ham, and Welsh haf, all meaning summer.

The PIE root sm is also the source of Proto-Germanic sumra, Old Saxon, Old Norse, Old High German sumar, Old Frisian sumur, Middle Dutch somer, Dutch zomer, German Sommer, and Old English sumor—all meaning summer. Old Norse sumarsdag, the first day of summer, was the Thursday that fell between April 9 and 15.

Those of you with a carpentry background will know that the late 13th century word summer refers to a horizontal bearing beam in a timber-framed building; but let that be another story.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on June 23, 2021 09:40

June 17, 2021

Hello!

When did people first start saying, “Hello,” to one another?

When did people first start saying, “Hello,” to one another?When the word hello first appeared in the early 19th century, it was a way of getting someone’s attention (“Hello! Get away from there!”) or a way to express surprise (“Hello! What have we here?”). However, by 1848, hello was also becoming a popular greeting between persons meeting one another, especially in the frontier country of the American West.

What did people say before that when they met each other?

The origins of the word hello are uncertain. Hello is a variation on holla or hollo (a shout to attract attention) from, perhaps, the late 14th century. Or perhaps hello comes from Middle English halouen (a shout during a chase while hunting). Or from Old High German hala, hola (to fetch; particularly when hailing a ferryman). Or Anglo-Saxon hal (hale; as in ‘hale and hearty’). Or from Old Norse heill (health, prosperity, good luck) or Old English waes haeil (“Be healthy”); i.e., wassail, “Here we come a-wassailing”, as in the Christmas carol.

Perhaps hello comes from 12th century heilen (hail; to call from a distance), the source of ‘to hail’ (to greet or to address; e.g., “Hail Mary” or “Hail to the Chief”; and, to drink toasts; e.g., “Let’s hail the New Year!”). “Hail fellow well met” is a greeting from the 1580s.

There are numerous ancient variations of the word hello—halloo, hallo, halloa, halloo, hillo, hilloa, holla, holler, hollo, holloa, hollow, hullo, and others.

The invention of the telephone in the 1870s raised a puzzling question: When answering the phone, what do you say? Some early responses might have included: “Yes?” or “Welcome” or “Jane here” or “Good morning” or “What?” or “Are you there?” or “Who is this?” Hmmm…

Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, advocated for the answer, “Ahoy” (from Dutch hoi = hello). However, Thomas Edison favored the use of “Hello”, the word being used more and more at that time in American English as a greeting and so used his influence to ensure that ‘hello’ is what got stuck into the language.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Crystal, D. (2011). The story of English in 100 words. New York: Picador, 163.

https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2011/02/17/133785829/a-shockingly-short-history-of-hello

Published on June 17, 2021 10:15

June 9, 2021

Garbage, Rubbish, or Trash??

Garbage? Rubbish? Trash? What’s the difference?

Garbage? Rubbish? Trash? What’s the difference?Garbage

The origins of the word garbage are unknown. When the word came to English in the 1580s garbage meant giblets, refuse of a fowl, or waste parts of an animal used for food. Garbage, meaning worthless, offensive stuff, is from the 1590s.

The sense of garbage as waste material is related to the verb ‘to garble’ which originally meant to sift refuse material from spices. Garble is related to Latin cribellum (sieve) and Arabic gharbal, Italian garbellare, and French garbeler (all meaning to sift)

Garbage collector is from 1872. Garbage can is from 1901. Garbologist is from 1965. Garbology, the study of waste as a social science, is from 1976.

Rubbish

The origins of the word rubbish are also unknown. The word came to English as robous around 1400, perhaps related to the word rubble (rough irregular stones broken from larger masses; e.g., the rubble of a building after an earthquake or a war). The word rubble appears in the late 1300s. The word rubbish is from the late 15th century.

Trash

The origins of the word trash are unknown. The word trash (a thing of little use or value, waste, refuse, dross) came to English in the late 14th century perhaps from Old Norse tros (rubbish, fallen leaves and twigs) or Swedish trasa (rages, tatters).

Trash, meaning an ill-bred person, is from Shakespeare’s Othello (1604). Trash, used in the southern US to describe poor whites; i.e., ‘white trash’, appears in 1831. Trash meaning domestic refuse or garbage is American English is from 1906. Trash can is from 1914. To trash something meaning to discard it as worthless is from 1859. Trash meaning to destroy or vandalize is from 1970. Trash-talk is from 1989.

In sum….

All three words are now used synonymously. Generally speaking, the British tend to use rubbish whereas Americans tend to use garbage or trash. Garbage usually refers to food waste. Rubbish and trash refer to other waste materials. Rubbish and trash are also used disparagingly to refer to speech which is nonsense or perceived as incorrect. Trash is also used disparagingly in relation to people.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on June 09, 2021 20:09

June 6, 2021

Refugee

What are the origins of the word refugee?

What are the origins of the word refugee?“Refugees are people who have fled war, violence, conflict, or persecution and who have crossed an international boundary in order to find safety in another country” (https://www.unhcr.org/what-is-a-refugee.html).

Merriam-Webster defines a refugee as “one who flees; especially, a person who flees to a foreign country or power to escape danger or persecution”.

A refugee can be any person who is a member of a group which is being persecuted for whatever reasons in their home country. Anyone from this targeted group can be considered a refugee. Also, a refugee can be a particular person who has been targeted by an oppressive government, often for their religious or political views and actions (Stories from newcomers to Canada, https://sntc.squarespace.com/).

The word refugee has its origins in Latin fugere (to flee). Latin re- (back) + fugere + ium (a place for) = refugium (a taking refuge; a place to flee to). From these Latin origins came Old French refuge (hiding place) and refugier (to take shelter, to protect). The word refuge (shelter or protection from danger or distress) came to English in the late 14th century from Old French refuge.

In the 1680s, the word refugee (one who flees to a refuge or place of safety in a foreign country during times of persecution or political disorder) first appears in English. At this time, the word refugee referred in particular to the French Huguenots (i.e., French Calvinist Protestants) who were fleeing or migrating from France during the 17th century to avoid religious persecution.1

Until 1914 and the beginning of World War One, the word refugee generally meant ‘one seeking asylum’. However, following the outbreak of the war, the word refugee also came to mean ‘one fleeing from their home’.

Seems like the words ‘refuge’ and ‘refugee’ have always been needed. They have been around almost unchanged since the ancient days of Latin refugium.

Image: United Nations High Commission for Refugees (unhcr.org)

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

1 During the various religious Reformation movements of the 16th century, French Calvinist Protestants (known as Huguenots) were increasingly victims of religious persecution. In particular, the St Bartholomew’s Day (23 – 24 August 1572) massacre of Huguenots in Paris, allegedly instigated by the French royal family, marked the beginning of mob violence against Huguenots across France which lasted for several weeks. Thousands of Huguenots were killed. Thousands more fled the country.

The Edict of Nantes, enacted in 1598, was intended to counter such persecution and to protect and give equal rights to the Protestant citizens of Roman Catholic France. In spite of this, official and unofficial persecution continued. During the 1600s, many Huguenots fled from France to safe havens in other European countries, to the British colonies of North America, and to Africa. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 was marked by a second major wave of refugees from France.

Published on June 06, 2021 10:38