David Tickner's Blog, page 40

October 22, 2020

Werewolf

Belief in werewolves was widespread in the ancient and medieval world as seen, for example, in Middle Dutch werewolf, Old High German werewolf, Swedish varulf. The eighth month of the ancient Persian calendar (October-November) was Varkazana (month of the wolf men).

Belief in werewolves was widespread in the ancient and medieval world as seen, for example, in Middle Dutch werewolf, Old High German werewolf, Swedish varulf. The eighth month of the ancient Persian calendar (October-November) was Varkazana (month of the wolf men).A werewolf is a ‘man wolf’. The word comes from the combination of two Proto-Indo-European (PIE) roots: wi-ro (man) and wlkwo (wolf). Old English werewolf, a word unchanged in over a thousand years, meant a man with the power to turn into a wolf.

In ancient Greek, lykos (wolf) + anthropos (man) = lykanthropus (wolf man). In the 1580s, the term lycanthropy, from lykanthropus, was used to describe a form of madness in which the afflicted person thought he was a wolf. In the l620s, a lycanthrope was a man who imagines himself to be a wolf and who behaves as one. In 1825, the term lycanthrope was used to mean a werewolf; that is, a man who supernaturally transforms into a wolf.

Questions arise: in all these cultures over all these centuries, what were people seeing or experiencing that gave rise to the word werewolf? Why don’t we see or have these experiences today (other than in the movies)? Or do we, perhaps without recognizing their ancient origins?

If your curiosity has been sparked, see the link below for a discussion of the mythology of werewolves.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

The mythology of werewolves: https://www.etymonline.com/columns/post/wolf

Published on October 22, 2020 08:01

October 21, 2020

Haunt, Haunted

Do you ever think about going back to a place where you grew up or where you went to school? Do you think of going back going back to visit your old haunts? Is there a place that you never want to go back to? Haunts, that is, the places and neighbourhoods where you used to live.

Do you ever think about going back to a place where you grew up or where you went to school? Do you think of going back going back to visit your old haunts? Is there a place that you never want to go back to? Haunts, that is, the places and neighbourhoods where you used to live.The word haunt has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root tkei (to settle, dwell, be home), the source of Proto-Germanic haimaz (home) and haimatjanan (to go or bring home) and Old Norse heimta (bring home). The verb ‘to haunt’ comes to English in the early 13th century meaning to practice habitually or to busy oneself with; from Old French hanter (to visit regularly, be familiar with, indulge in). By around 1300, haunt also meant a place frequently visited.

In Middle English, haunt scole meant to attend school. Haunt also was used to mean ‘to have sexual intercourse with’—this gives another meaning to the term ‘haunted house’.

The use of haunt in reference to a ghost or spirit returning to the house where it had lived may have been of Proto-Germanic origins; however, if so, it was lost or buried until revived by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1590).

The contemporary meaning of haunt meaning the spirit that haunts a place or a ghost is first recorded in 1843 in African American Vernacular English.

The word haunted has evolved in meaning over the years. In the early 14th century haunted meant accustomed, by mid-14th century it meant stirred or aroused, by early 15th century it meant frequent. And then much-frequented (1570s), visited by ghosts (1711), and haunted house (1733).

Haunt could be said to be the spirit of a place which might explain why we like to return to our old haunts, to the places that have some good memories for us. We probably would not want to visit those ‘haunted’ places which hold negative memories.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 21, 2020 08:22

October 20, 2020

Skeleton, Mummy

Skeleton

SkeletonSkeletons have not changed that much over the centuries in either appearance or name. The word skeleton has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root skele (to parch, wither), the source of Greek sclerosis (hardening) and late 14th century English sclerosis (morbid hardening of tissue).

The word skeleton appears in English in the 1570s from Latin sceleton (bones, bony framework of the body), Greek skeleton soma (dried-up body, mummy, skeleton) and skeletos (dried up), and Greek skellein (to dry up, make dry, parch)—all from PIE skele.

Mummy

No, we are not talking about your Mum. By the way, ‘Mom’ is American English and ‘Mum’ is British English, just in case you were wondering. But I digress.

Mummy comes from Persian mumiya (asphalt) and mum (wax). From this source we see Arabic mumiyah and Latin mumia, both meaning an embalmed body. The word mummie comes to English in the late 14th century meaning a medicinal substance prepared from mummy tissue. The use of mummy to mean a dead body embalmed and dried after the manner of the ancient Egyptians comes to English in the 1610s.

The verb ‘to mummify’ (to embalm and dry a dead body as a mummy) is from the 1620s. Mummification, the process of making into a mummy, is from 1793. The state or fact of being a mummy is from 1857. The use of mummify meaning to shrivel or dry up is from 1864.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 20, 2020 08:03

October 19, 2020

Ghost, Specter, Spook

Ghost

GhostThe word ghost has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European root gheis (excitement, amazement, fear), the source of Proto-Germanic gaistaz (in turn, the source of Old Saxon gest, Dutch geest, German Geist, all meaning spirit or ghost; in particular, the disembodied spirit of a dead person. From these Germanic sources comes Old English gast or gaest (breath; good or bad spirit, angel, demon; person, man, human being; especially as used in the Biblical sense to mean soul, spirit, life) and Old English gaestan (to terrify).

In brief, ghost is a Germanic word meaning supernatural being. The related Latin term is spiritus (spirit); e.g., ‘Holy Ghost’ is a Germanic term; ‘Holy Spirit’ is the equivalent Latin term.

Ghost, as an English term meaning the spirit of a dead person wandering among the living or haunting them is from the late 14th century. Sounds ghastly.

A poltergeist (a noisy spirit or ghost which makes its presence known by noises) is from 1838 from German Poltergeist (literally, ‘noisy ghost’).

The words aghast and ghastly (terrified, filled with frightened amazement), from around 1300, are from Middle English agasten (to frighten) and Old English gaest (ghost).

Specter

From around 1600, meaning a frightening ghost, from Latin spectrum (appearance, vision, apparition). Specter as an object of dread is from 1774.

Spook

Spook is first seen in English in 1801, meaning specter, apparition, ghost, from Dutch spook, Middle Dutch spooc (spook, ghost), German Spuk (ghost, apparition), and other Germanic words. The original root of the word is unknown. Spooky, meaning frightening, is from 1854. The verb ‘to spook’ meaning to unnerve is from 1935.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 19, 2020 08:03

October 18, 2020

Monster

Do you ever have dark thoughts? Do you ever imagine awful things happening? Particularly when you wake up at two in the morning with such thoughts and can’t get back to sleep?

Do you ever have dark thoughts? Do you ever imagine awful things happening? Particularly when you wake up at two in the morning with such thoughts and can’t get back to sleep?The word monster has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root men (to think) and PIE moneie (to make one think of, to remind). These terms are the source of Latin monere (to remind, to bring to one’s recollection) and monstrum (divine omen, especially one indicating misfortune; portent, sign; abnormal shape; monster, monstrosity).

In the early 14th century the word monstre (malformed animal or human, creature afflicted with a birth defect) came to English from Old French monstre (monster, monstrosity) and Latin monstrum, eventually evolving to the word monster.

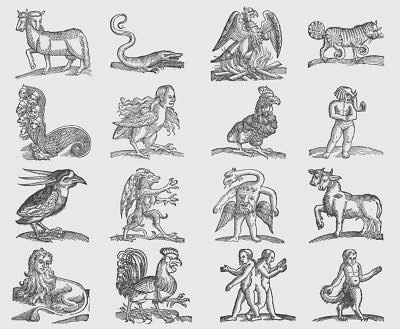

At that time, abnormal animals were regarded as signs or omens of impending evil. By the late 14th century we see diagrams of animals embodying parts of various creatures; e.g., centaurs or griffins (or mermaids or unicorns!). Today we might say that such signs are products of an unruly or overworked or fantastic (i.e., from fantasy) imagination.

In the 1520s, the word monster was used to describe an animal of enormous size. In the 1550s, monster was used to describe with horror people who exhibited cruelty or some other moral deformity. By the 19th century, monster was used to describe something of unusual size—today we have ‘monster’ truck derbys!

In brief, monsters would first of all seem to be products of our thoughts (today, we do not think of people with birth defects as monsters). However, this is not to say that there are still not real monsters of various types out there in the world.

You may be happy to know that PIE men (to think) is not just about thinking of monsters and other dark thoughts. Several other words come from this root, including admonish, amnesia, amnesty, comment, dement, demonstrate, idiomatic, mania, mental, mention, mentor, mind, mnemonic, money, monitor, monument, mosaic, muse, museum, music, muster, premonition, reminiscence, summon, and others.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 18, 2020 12:06

October 17, 2020

Pumpkin, Jack O'Lantern

Pumpkin

PumpkinThe word pumpkin has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European root pekw (to cook, to ripen), the source of Greek pepon (melon), a word that was a generic term for any fruit not local to Greece. In the 1540s, the words pompone and pumpion appear in English from Middle French pompon (melon). By the 1640s, the word pumpkin is seen in English. [On a side note, the Old English word aeppel (apple) was used similarly as a generic term for any fruit other than berries.]

Pumpkin pie is from the 1650s. Pumpkin head, from 1781, refers to a person with hair cut short all around. An alternative spelling in American English, punkin, appears in 1806.

Jack O’Lantern

In medieval times, people sometimes saw flickering light appearing at night over marshy ground. I can imagine that in those days some might have found this phenomenon somewhat spooky. This light was called Jack’s lantern or jack of the lantern or jack o’lantern.

Another name for this light was ‘will o’the wisp’; i.e., Will’s wisp (Will’s torch), a term from the 1660s. This mysterious light is now attributed to the combustion of gases from decomposing organic matter. In 1563, scientists named this natural phenomenon ignis fatuus (foolish fire).

The custom of carving jack o’lanterns from pumpkins at Halloween is believed to originate in 19th century Ireland and Scotland. Halloween, also known as Samhain, an ancient Celtic festival, was a time when supernatural beings and the souls of the dead walked the earth (the souls of both good and evil people, I might add), a time when the boundaries between the living and the dead were more porous than at other times. A pumpkin with a carved scary face and a candle, set in a window, was a way to keep the harmful or evil spirits away from one’s home on a such a dark night.

On Halloween, 1835, the Dublin Penny Journal published a story on the Jack o’the Lantern. At that time the terms O’Lantern and McLantern were both used, a reflection of the Irish and Scottish use of pumpkins as lanterns to ward off the evil spirits.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack-o%27-lantern

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ignis%20fatuus

Published on October 17, 2020 12:08

October 16, 2020

Pencil

To get right to the point, the word pencil has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word pes (penis) and Latin penis (penis; and, earlier, a tail) and Latin peniculus (brush).

(I would like to be able to say that the word ‘piss’ comes from PIE pes but there is no evidence for this. Most sources suggest that ‘piss’ comes from the sound of someone pissing; e.g., Latin pissiare, but that’s another story).

Anyway, Latin peniculus (brush) and penicillus (painter’s brush, hair pencil—literally, ‘little tail’) are the source of Old French pincel (artist’s paintbrush). By the mid-14th century, the word pencel came to English, meaning an artist’s small, fine brush of camel hair used for painting, manuscript illustration, and so on. [Also: penicillus is the origin of the word penicillin, yet another story].

From the mid-16th century, the word pencil was being used to describe a ‘graphite writing instrument’ in contrast to the pencel brush. At first, a pencil was a stick of pure graphite that was used for writing and marking things (note that a ‘lead pencil’ is not made with lead). At about same time, the wooden enclosures or holders for these graphite sticks were being developed. The graphite and its wooden container became known as a pencil.

After the modern clay-graphite mix was developed in the 19th century, the mass production of pencils began. The pencil with an eraser on the end is from 1858.

Why are pencils often yellow? In brief, during the 19th century, some of the best graphite in the world for pencils was found in the northern parts of China bordering on Russian Siberia. The color yellow was chosen for these top-quality pencils because of the associations of yellow with China and with royalty in Asia. As well at that time, the Koh-i-Noor yellow pencil was named for the legendary Asiatic Koh-i-Noor diamond. To this day, most pencils are yellow.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1994/11/15/wonder-why-your-pencils-yellow/5cc73edc-6fc3-4f94-b4ef-fbd04a58ab49/

(I would like to be able to say that the word ‘piss’ comes from PIE pes but there is no evidence for this. Most sources suggest that ‘piss’ comes from the sound of someone pissing; e.g., Latin pissiare, but that’s another story).

Anyway, Latin peniculus (brush) and penicillus (painter’s brush, hair pencil—literally, ‘little tail’) are the source of Old French pincel (artist’s paintbrush). By the mid-14th century, the word pencel came to English, meaning an artist’s small, fine brush of camel hair used for painting, manuscript illustration, and so on. [Also: penicillus is the origin of the word penicillin, yet another story].

From the mid-16th century, the word pencil was being used to describe a ‘graphite writing instrument’ in contrast to the pencel brush. At first, a pencil was a stick of pure graphite that was used for writing and marking things (note that a ‘lead pencil’ is not made with lead). At about same time, the wooden enclosures or holders for these graphite sticks were being developed. The graphite and its wooden container became known as a pencil.

After the modern clay-graphite mix was developed in the 19th century, the mass production of pencils began. The pencil with an eraser on the end is from 1858.

Why are pencils often yellow? In brief, during the 19th century, some of the best graphite in the world for pencils was found in the northern parts of China bordering on Russian Siberia. The color yellow was chosen for these top-quality pencils because of the associations of yellow with China and with royalty in Asia. As well at that time, the Koh-i-Noor yellow pencil was named for the legendary Asiatic Koh-i-Noor diamond. To this day, most pencils are yellow.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1994/11/15/wonder-why-your-pencils-yellow/5cc73edc-6fc3-4f94-b4ef-fbd04a58ab49/

Published on October 16, 2020 12:21

October 14, 2020

Freelance

Freelance is a word coined by Sir Walter Scott in his 1820 book, Ivanhoe, in which a ‘free lance’ was a medieval mercenary warrior.

Freelance is a word coined by Sir Walter Scott in his 1820 book, Ivanhoe, in which a ‘free lance’ was a medieval mercenary warrior.The sense of ‘freelance’ as an independent worker is from 1864. Freelance journalist is from 1882. Freelancer is from 1898. The verb ‘to freelance’ is from 1902.

A related term is paladin, from Old French palaisin and Italian paladino, meaning an independent warrior for hire. Paladin as a ‘heroic champion’ is from 1788. Some of you may remember the TV series (1957 – 1963) “Have Gun Will Travel” featuring a main character called Paladin, a sort of Robin Hood, ‘rob from the rich, give to the poor’ kind of guy.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 14, 2020 17:17

October 12, 2020

Musa Sapientum

Do you ever get frustrated trying to figure out something or remember something: “What’s his name again?” Have you ever wrestled with trying to learn something new and you just can’t get it? Learning anything takes time and effort and energy. The term ‘Zoom fatigue’ comes to mind.

At such moments, you may hear the old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try try again.” Or perhaps you hear, “Think smarter, not harder.”

I would suggest that you might want to try something different: reach for a musa sapientum.

“What’s a musa sapientum?” you might ask. Good question. Bear with me.

Musa is a Latin word which comes from Greek mousa (muse, music, song) and from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root men (to think, to remember). Musa comes to English in the 14th century as muse, a noun meaning protector of the arts.

The 14th century verb ‘to muse’ (to reflect, to be absorbed in thought) comes from Old French muser (to ponder, to dream; also, to loiter, waste time, or stand with your nose in the air, like a dog who has lost the scent.

The word muse is related to words such as amuse, bemuse, mosaic, museum, music, and perhaps muzzle.

Sapientum, a Latin word with meanings related to wisdom, understanding, and knowing, comes from Latin sapere (to taste, to have taste, to be wise) from the PIE root sep (to taste, perceive). Sapientum is the root of the word sapience (good taste, good sense, intelligence, wisdom, understanding, discernment). The word savvy is also rooted in sapientum. In 1802 the Latin term homo sapiens was coined as the scientific term for human beings: homo (man or human being) + sapiens (knowing) = a ‘knowing being’.

So, speaking of scientific names, we come back to Latin musa sapientum (the inspiration for knowledge, muse of the wise). And if, as I previously suggested, that you reach for a musa sapientum in order to help you learn something, what exactly would you be reaching for? Check in your kitchen.

You may be surprised to learn that musa sapientum was an 18th century Latin or scientific name for the humble banana.

Determining the Latin or scientific name for the banana has had a bumpy history due to ongoing botanical research and discoveries over the years. The name musa sapientum may have been chosen as much for poetic as for scientific reasons; that is, Latin musa simply sounds a lot like the Arabic word for banana, mauz. Another scientific name given to the banana was musa paradisiaca (muse of paradise). At one time, the banana was also known as musa cliffortiana, after an 18th century botanist who grew bananas in a greenhouse in the Netherlands. Part of the struggle with naming may have come because of difficulties in trying to figure out and learn the difference between plantains and bananas. Anyway…

So, musa sapientum or musa paradisiaca? Take your pick!

The actual word banana, by the way, is a West African word.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banana

At such moments, you may hear the old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try try again.” Or perhaps you hear, “Think smarter, not harder.”

I would suggest that you might want to try something different: reach for a musa sapientum.

“What’s a musa sapientum?” you might ask. Good question. Bear with me.

Musa is a Latin word which comes from Greek mousa (muse, music, song) and from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root men (to think, to remember). Musa comes to English in the 14th century as muse, a noun meaning protector of the arts.

The 14th century verb ‘to muse’ (to reflect, to be absorbed in thought) comes from Old French muser (to ponder, to dream; also, to loiter, waste time, or stand with your nose in the air, like a dog who has lost the scent.

The word muse is related to words such as amuse, bemuse, mosaic, museum, music, and perhaps muzzle.

Sapientum, a Latin word with meanings related to wisdom, understanding, and knowing, comes from Latin sapere (to taste, to have taste, to be wise) from the PIE root sep (to taste, perceive). Sapientum is the root of the word sapience (good taste, good sense, intelligence, wisdom, understanding, discernment). The word savvy is also rooted in sapientum. In 1802 the Latin term homo sapiens was coined as the scientific term for human beings: homo (man or human being) + sapiens (knowing) = a ‘knowing being’.

So, speaking of scientific names, we come back to Latin musa sapientum (the inspiration for knowledge, muse of the wise). And if, as I previously suggested, that you reach for a musa sapientum in order to help you learn something, what exactly would you be reaching for? Check in your kitchen.

You may be surprised to learn that musa sapientum was an 18th century Latin or scientific name for the humble banana.

Determining the Latin or scientific name for the banana has had a bumpy history due to ongoing botanical research and discoveries over the years. The name musa sapientum may have been chosen as much for poetic as for scientific reasons; that is, Latin musa simply sounds a lot like the Arabic word for banana, mauz. Another scientific name given to the banana was musa paradisiaca (muse of paradise). At one time, the banana was also known as musa cliffortiana, after an 18th century botanist who grew bananas in a greenhouse in the Netherlands. Part of the struggle with naming may have come because of difficulties in trying to figure out and learn the difference between plantains and bananas. Anyway…

So, musa sapientum or musa paradisiaca? Take your pick!

The actual word banana, by the way, is a West African word.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banana

Published on October 12, 2020 19:28

October 9, 2020

Thanksgiving

Happy Thanksgiving!

Happy Thanksgiving!The word thanksgiving is straight forward and unchanging in its origins and meanings. People have always had experiences for which thankfulness is the response. How interesting and how humbling, how down to earth, to have a public holiday based on giving thanks.

Thank

The word thank has its origins in the ancient Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root tong (to think, to feel); that is, thinking or being mindful of feeling; particularly feelings of gratitude. From PIE tong comes Proto-Germanic thankojanan and thankoz (thought, gratitude), words which are the origin of others such as Old Saxon thancon, Old Frisian thankia, Old High German danchon, Middle Dutch, Dutch, and German danken—all meaning ‘to thank’. You can see (and hear) the origins of the English word ‘thank’ in these words. People of the Indo-European language family have been saying “Thank You” and expressing gratitude using almost the same sounds or words for thousands of years.

To say ‘thank you’ is an act of intention—a purposeful pause and expression of thanks and gratitude.

Give, giving

The word give comes from the PIE root ghabh which meant both to give and to receive, like the two sides of a coin. We receive something and we give thanks. When we give thanks, we give someone something to receive. If nothing else, we give our gratitude. Like the word thanks, the word give has not changed that much over the centuries.

Thanksgiving

The word thanksgiving appears in English in the 1530s.

In Canada, the first record of a ‘thanksgiving’ meal is from 1578 when the explorer Martin Frobisher gave thanks for safe arrival in the Arctic at what is now known as Iqaluit. Until 1957, Thanksgiving was an unofficial holiday in Canada and was celebrated at various times as part of harvest festivals and other celebrations. In 1957, Thanksgiving became an official Canadian holiday, celebrated on the second Monday of October.

The first American Thanksgiving was held by the Plymouth Colony Pilgrims in 1621. The holiday, now celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November, is from the 1670s.

It is noted that some Thanksgiving events, particularly those involving indigenous peoples, are seen now from a colonial perspective. The role of indigenous peoples in these events of the past is subject to conjecture and to various interpretations from various points of view.

New perspectives—yet another reason for feeling gratitude and giving thanks.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 09, 2020 20:13