David Tickner's Blog, page 42

September 6, 2020

Farmer

Would you be surprised to learn that the word farmer originally meant someone who collected taxes? I was.

Would you be surprised to learn that the word farmer originally meant someone who collected taxes? I was.The word farm comes from Latin firmus (strong, stable) and firmare (to fix, settle, confirm, strengthen). Medieval Latin firma meant a fixed payment, from which comes 13th century Old French ferme (a rent, lease). The word farm comes to English around 1300 at which time it meant a fixed payment in exchange for taxes collected or a fixed rent.

The use of the word farm to mean ‘a tract of leased land’ is from the early 14th century. The word farm meaning cultivated land is from the 1520s. The word farmer is first seen in the 1590s when it replaced the older words churl and husbandman; i.e., people who worked or farmed land owned by someone else.

The use of the words farm and farmer in terms of ‘agriculture’ and ‘farming’ is relatively modern. The exact dates of when and how this change in meaning evolved from ‘tax collection’ and ‘cultivated land’ are uncertain.

Until recent times, in Europe, land was owned by the aristocracy who hired farm labour to work their estates (many of my 19th century ancestors are listed as “Farm labourer” in census and genealogical records). In contrast, many immigrants of the 19th and 20th centuries were attracted to North American by the promise of ‘free land’; i.e., owning and working your own land.

Speaking of farmers, do you know anyone named George? The name comes from a combination of Greek ge, geo (earth) from Gaia (Mother Earth in Greek mythology) and Greek ergon (work), from which we get ergonomics (the study of work). That is, geo + ergon = earth worker = Georgos (farmer).

The word ‘work’ hasn’t changed that much over the millenia—the Proto-Indo-European root of Greek ergon is werg (to do).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 06, 2020 21:05

September 4, 2020

Labour Day

Labour

How are the words labour and work different? Or the same? Generally speaking, work is ‘what’ gets done and labour is ‘how’ work gets done. (‘Labour’ is the British and Canadian spelling; ‘labor’ is the American spelling).

Labour has its origins in Latin labor (toil, exertion; hardship, pain, fatigue; a work, a product of labor). Before that, the origin of the word is uncertain. The word labour comes to English around 1300 meaning a task or project, and later meaning exertion of the body; trouble, difficulty, hardship. In brief, labour means the physical and mental energy required to do a task.

Labour, as the physical exertions of childbirth, is from the 1590s. Labour, meaning a body of labourers considered as a class, is from 1839.

The verb ‘to labour’, from the late 14th century, meant to perform manual or physical work; work hard; keep busy; take pains, strive, endeavor; also, to copulate! (It’s a tough job but someone has to do it). The verb ‘to labour’ comes from Old French laborer and Latin laborare (to work, endeavor, talk pains, exert oneself; produce by toil; suffer, be afflicted; be in distress or difficulty).

Labourer (manual worker, often unskilled) is from the mid-14th century. Laborer meaning a member of the working class, the lowest social rank, is from around 1400.

Laboratory, a room or building set apart for scientific experiments, is from around 1600 and has its origins in medieval Latin laboratorium.

Day

In Old English daeg meant the period during which the sun is above the horizon. Only later did a day mean a 24-hour period. Old English daeg is one of many words meaning day that come from Proto-Germanic dages (day); for example, Old Saxon, Middle Dutch, Dutch dag, Old Frisian dei, Old High German tag, German Tag, and Old Norse dagr. These words have their origin in one or both of two Proto-Indo-European roots—agh (a day) and dhegh (to burn).

Labour Day

Labor Day was first marked in 1882 in New York City. Labour Day was recognized as a statutory holiday in Canada in 1894.

Enjoy the long weekend!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

How are the words labour and work different? Or the same? Generally speaking, work is ‘what’ gets done and labour is ‘how’ work gets done. (‘Labour’ is the British and Canadian spelling; ‘labor’ is the American spelling).

Labour has its origins in Latin labor (toil, exertion; hardship, pain, fatigue; a work, a product of labor). Before that, the origin of the word is uncertain. The word labour comes to English around 1300 meaning a task or project, and later meaning exertion of the body; trouble, difficulty, hardship. In brief, labour means the physical and mental energy required to do a task.

Labour, as the physical exertions of childbirth, is from the 1590s. Labour, meaning a body of labourers considered as a class, is from 1839.

The verb ‘to labour’, from the late 14th century, meant to perform manual or physical work; work hard; keep busy; take pains, strive, endeavor; also, to copulate! (It’s a tough job but someone has to do it). The verb ‘to labour’ comes from Old French laborer and Latin laborare (to work, endeavor, talk pains, exert oneself; produce by toil; suffer, be afflicted; be in distress or difficulty).

Labourer (manual worker, often unskilled) is from the mid-14th century. Laborer meaning a member of the working class, the lowest social rank, is from around 1400.

Laboratory, a room or building set apart for scientific experiments, is from around 1600 and has its origins in medieval Latin laboratorium.

Day

In Old English daeg meant the period during which the sun is above the horizon. Only later did a day mean a 24-hour period. Old English daeg is one of many words meaning day that come from Proto-Germanic dages (day); for example, Old Saxon, Middle Dutch, Dutch dag, Old Frisian dei, Old High German tag, German Tag, and Old Norse dagr. These words have their origin in one or both of two Proto-Indo-European roots—agh (a day) and dhegh (to burn).

Labour Day

Labor Day was first marked in 1882 in New York City. Labour Day was recognized as a statutory holiday in Canada in 1894.

Enjoy the long weekend!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 04, 2020 22:12

September 3, 2020

Syllabus

Have you ever wrapped an elastic band around a stack of papers in order to keep them organized or to keep them from getting scattered? Have you ever put a post-it or some other kind of label on such a stack to remind yourself of what’s in the pile? I used to have piles of student assignments to be marked on my desk—a pile for each course. Now I have stacks of paper on my desk related to my different retirement projects.

In the past, bureaucrats or office workers wrapped files, notes, and other bundles of paper in red ribbon or tape. As you might expect, this is the origin of the phrase ‘red tape’!

In ancient Greece, before the invention of post-its or elastic bands or red tape, scholars or clerks wrapped documents with a strip of leather called a sittybos (a parchment label, a table of contents), which is a word of unknown origin.

During the Roman Empire, Greek sittybos became the Latin word sillybus, apparently the result of a misreading or mistranslation. Latin sillybus was a strip of parchment used to wrap around a scroll or codex (i.e., a small book) and which was used as a label for this scroll or codex.

The word sillybus evolved to be the word syllabus, first seen in English in 1656. By that time, the word syllabus had come to mean a summary outline of a document. We now use the word syllabus to mean a short document which summarizes the key points of a course or program.

And, of course, a syllabus should not be confused with a syllabub—a traditional frothy creamy dessert concoction from England.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

In the past, bureaucrats or office workers wrapped files, notes, and other bundles of paper in red ribbon or tape. As you might expect, this is the origin of the phrase ‘red tape’!

In ancient Greece, before the invention of post-its or elastic bands or red tape, scholars or clerks wrapped documents with a strip of leather called a sittybos (a parchment label, a table of contents), which is a word of unknown origin.

During the Roman Empire, Greek sittybos became the Latin word sillybus, apparently the result of a misreading or mistranslation. Latin sillybus was a strip of parchment used to wrap around a scroll or codex (i.e., a small book) and which was used as a label for this scroll or codex.

The word sillybus evolved to be the word syllabus, first seen in English in 1656. By that time, the word syllabus had come to mean a summary outline of a document. We now use the word syllabus to mean a short document which summarizes the key points of a course or program.

And, of course, a syllabus should not be confused with a syllabub—a traditional frothy creamy dessert concoction from England.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 03, 2020 21:02

September 2, 2020

Respair

Ever been a desperado? Did a well-meaning friend ever ask, “Why don’t you come to your senses?” Try respairing.

The word desperado (a person in despair) comes to English around 1600 from Spanish and earlier from Latin desperatus (given up, despaired of).

In its origins, desperado comes from the Proto-Indo-European root spes (prosperity), Latin spes (hope), and Latin sperare (to hope). The Latin prefix de- (without) + sperare makes desperare (to despair, to lose all hope), a word which came to English in the early 14th century as despair (hopelessness, total loss of hope). The verb ‘to despair’ (to lose hope, to be without hope) came to English in the mid-14th century. By the late 14th century, the word desperation appears. (It may be worth mentioning that the mid-14th century was marked by the Black Death plague).

However, at this time, the word respair was used to mean the return of hope after a period of despair. There seems an element of choice in this word; for example, “After being down in the dumps for a while, I respaired.” Have you ever had the experience of respair or respairing?

If you did, you probably wouldn’t have had a word for it. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the last known use of the word respair was 1425. It is hard to believe that people don’t have a desire for such a useful word.

In the meantime, perhaps the Eagles can help out…

Desperado, why don’t you come to your senses

You’ve been out ridin’ fences for so long now…

Desperado

Oh, you ain’t getting no younger

Your pain and your hunger

They’re driving you home

And freedom, oh, freedom

Well that’s just some people talking

Your prison is walking through this world all alone

Desperado

Why don’t you come to your senses?

Come down from your fences, open the gate

It may be rainin’, but there’s a rainbow above you

You better let somebody love you

(Let somebody love you)

You better let someone love you

Before it’s too late.

“Desperado” (excerpts from the 1970’s song by the Eagles). Apologies to readers who were not born at that time! Linda Ronstadt did a classic cover version of the song. Diana Krall’s recent cover is also great.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://genius.com/Eagles-desperado-lyrics

Johnson. (4 March 2017). Lexical treasures: Why words die (and how to stop a few of them from keeling over). The Economist, p. 69.

The word desperado (a person in despair) comes to English around 1600 from Spanish and earlier from Latin desperatus (given up, despaired of).

In its origins, desperado comes from the Proto-Indo-European root spes (prosperity), Latin spes (hope), and Latin sperare (to hope). The Latin prefix de- (without) + sperare makes desperare (to despair, to lose all hope), a word which came to English in the early 14th century as despair (hopelessness, total loss of hope). The verb ‘to despair’ (to lose hope, to be without hope) came to English in the mid-14th century. By the late 14th century, the word desperation appears. (It may be worth mentioning that the mid-14th century was marked by the Black Death plague).

However, at this time, the word respair was used to mean the return of hope after a period of despair. There seems an element of choice in this word; for example, “After being down in the dumps for a while, I respaired.” Have you ever had the experience of respair or respairing?

If you did, you probably wouldn’t have had a word for it. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the last known use of the word respair was 1425. It is hard to believe that people don’t have a desire for such a useful word.

In the meantime, perhaps the Eagles can help out…

Desperado, why don’t you come to your senses

You’ve been out ridin’ fences for so long now…

Desperado

Oh, you ain’t getting no younger

Your pain and your hunger

They’re driving you home

And freedom, oh, freedom

Well that’s just some people talking

Your prison is walking through this world all alone

Desperado

Why don’t you come to your senses?

Come down from your fences, open the gate

It may be rainin’, but there’s a rainbow above you

You better let somebody love you

(Let somebody love you)

You better let someone love you

Before it’s too late.

“Desperado” (excerpts from the 1970’s song by the Eagles). Apologies to readers who were not born at that time! Linda Ronstadt did a classic cover version of the song. Diana Krall’s recent cover is also great.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://genius.com/Eagles-desperado-lyrics

Johnson. (4 March 2017). Lexical treasures: Why words die (and how to stop a few of them from keeling over). The Economist, p. 69.

Published on September 02, 2020 07:58

August 29, 2020

Carpenter

Can you see the word ‘car’ in carpenter? This a big hint about the origins of the word carpenter.

Can you see the word ‘car’ in carpenter? This a big hint about the origins of the word carpenter.The word carpenter comes from the Proto-Indo-European root kers (to run) which is the source of words such as Old Irish carpat and Gaelic carbad (carriage) and Gaulish karros (chariot). From these words come Latin carpentum (a wagon, two-wheeled carriage, cart) and carpentarius (wagon maker, carriage maker, cartwright).

PIE kers (to run) is also the root of car, career, courier, currency, curriculum (how often does this course ‘run’?), horse, and many other words. (I can’t resist taking the opportunity to say that when I was doing curriculum development work with automotive instructors, they would insist on talking about their ‘carriculum’. But I digress.)

At this point, you might ask, “What is the Latin word for carpenter?” Answer: Lignarius; from lignum (wood, tree).

Before the Norman-French invasion of England in 1066, the Anglo-Saxon word for carpenter was treowwyrtha (treewright; like millwright, wheelwright, cartwright, and so on).

The word ‘carpenter’ is first seen in English in the early 12th century as a surname (Mr. Carpenter). By the early 1300s the word carpenter meant someone who worked with timber or who did heavy wood-working (i.e., houses or barns rather than furniture).

This English word carpenter came from Anglo-French carpenter, Norman French carpentier, and Old French charpentier, all of which came from Latin carpentarius.

So: how did the word for wagon maker end up as the word for woodworker or carpenter?

As late at the 7th century, the word lignarius was still used to mean carpenter. For example, in the late sixth or early seventh centuries a Latin translation of a Byzantine Greek biography of Joseph, father of Jesus, is titled Historia Josephi Fabri Lignari; i.e., ‘a history of Joseph the wood worker’.

Somehow, between the 7th century and 1066 (roughly the so-called ‘Dark Ages’), the meaning of carpentarius changed. Why? At this point, in the research I have done, I cannot find the answer. I am reminded of the phrase ‘lost in translation’.

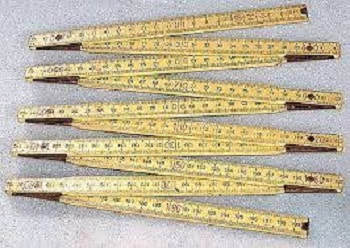

Anyway, the word carpentry (the art of cutting, framing, joining woodwork), from Old French carpenterie, appears in the late 14th century. Originally, Latin carpentaria meant a carriage-maker’s workshop; however, Medieval Latin carpentaria meant a carpenter’s shop. The term ‘carpenter’s rule’ (a foldable ruler, suitable for carrying in a pocket) is from the 1550s.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on August 29, 2020 14:26

August 27, 2020

Hypocrisy

“A number of different things might pop to mind when we hear the word hypocrite. Maybe it’s a politician caught in a scandal; maybe it’s a religious leader doing something counter to their creed; maybe it’s a scheming and conniving character featured in soap operas. But it’s likely that the one thing that doesn’t come to mind is the theatre” (Merriam-Webster).

Hypocrisy is about acting. The word hypocrisy comes from ancient Greek hypokrinesthai (to play a part, to pretend) and hypokrisis (acting on the stage; pretense). Actors in Greek plays wore masks to indicate the role that they were playing. The actor ‘under’ the mask (Greek hypo = under) was not the character which they were embodying in the drama.

By around 1200, the word ipocrisie (the sin of pretending to virtue or goodness), now hypocrisy (the ‘h’ shows up in the 16th century), had come to English. “Hypocrisy is the art of affecting qualities for the purpose of pretending to an undeserved virtue” Online Etymological Dictionary.

The word hypocrite (false pretender to virtue or religion), from Greek hypocrite (an actor), also comes to English around 1200. In the 13th century, a hypocrite was someone who pretended to be morally good or pious in order to deceive others. By the early 1700s, hypocrite was used to mean a person who acts in contradiction to their stated beliefs or feelings.

How can we describe the hypocritical actions of such hypocrites? If they don’t know they’re playing a role or speaking a script written by others, it would seem that they are woefully ignorant or naive. If they do know they are playing a role, then they are clearly conning or manipulating people. The difference between such hypocritical activity and actual theatre acting is that we know and the actors know that they are acting.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/hypocrite-meaning-origin

Hypocrisy is about acting. The word hypocrisy comes from ancient Greek hypokrinesthai (to play a part, to pretend) and hypokrisis (acting on the stage; pretense). Actors in Greek plays wore masks to indicate the role that they were playing. The actor ‘under’ the mask (Greek hypo = under) was not the character which they were embodying in the drama.

By around 1200, the word ipocrisie (the sin of pretending to virtue or goodness), now hypocrisy (the ‘h’ shows up in the 16th century), had come to English. “Hypocrisy is the art of affecting qualities for the purpose of pretending to an undeserved virtue” Online Etymological Dictionary.

The word hypocrite (false pretender to virtue or religion), from Greek hypocrite (an actor), also comes to English around 1200. In the 13th century, a hypocrite was someone who pretended to be morally good or pious in order to deceive others. By the early 1700s, hypocrite was used to mean a person who acts in contradiction to their stated beliefs or feelings.

How can we describe the hypocritical actions of such hypocrites? If they don’t know they’re playing a role or speaking a script written by others, it would seem that they are woefully ignorant or naive. If they do know they are playing a role, then they are clearly conning or manipulating people. The difference between such hypocritical activity and actual theatre acting is that we know and the actors know that they are acting.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/hypocrite-meaning-origin

Published on August 27, 2020 21:36

August 25, 2020

Knowledge

The words know and knowledge are not just about the mind. The etymology tells us that these words are about both body and mind, thought and feeling.

The words know and knowledge are not just about the mind. The etymology tells us that these words are about both body and mind, thought and feeling.The words know and knowledge have their origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gno (to know). The everyday word ‘know’ came to English from PIE gno via Proto-Germanic knew and Old English cnawen (to perceive a thing to be identical with another; to be able to distinguish; to know how to do something; and to perceive or understand something as a fact or truth (which is not the same as belief which comes from PIE leubh = to care, desire, love—etymologically speaking, knowledge is what we ‘know’ whereas belief is what we ‘love’).

Many words come to English from PIE gno including agnostic, diagnosis, gnome, gnostic, ignoble, ignore, ignorant, prognosis, recognize, and so on. Also, PIE gno is the source of the more intellectual or literary words related to ‘know’ (e.g., cognition, cognitive, cognizant, and so on).

By 1200, the word know meant to experience or to live through. A person ‘knew’ something with all their senses. As well, at that time, in English and other modern languages, ‘know’ also meant to have sexual intercourse, as seen, for example, in early English translations of the Bible (Genesis 4.1: “Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived…”).

Similarly, the word knowledge comes to English in the early 12th century as cnawlece (acknowledgement of a superior, honor, worship). By the late 14th century, knowledge meant a capacity for knowing, understanding, familiarity; a fact or condition of knowing, awareness of a fact; news, notice, information, learning; and an organized body of fact or teachings. By the beginning of the 15th century, the word knowledge, like the word know, also meant to have sexual intercourse with someone, in the sense of to have ‘carnal knowledge’ of someone.

However, during the years of the Renaissance, Reformation, and Enlightenment (~15th – 18th centuries), the word knowledge became more and more associated with the workings of the brain and mind. Even so, even today we talk of people who ‘think’ with their genitals!

Nevertheless, today when we ask the question of ‘how’ we know, one answer is that knowing is a function of our bodily senses and our perceptions in conjunction with our brain. Knowledge is not just in our head, it is in our body. Our bodies can ‘know’ things—like swinging a tennis racket or dancing or sanding a piece of pine to perfection when crafting a cabinet.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on August 25, 2020 21:45

August 24, 2020

Engineer

Do you know any engineers? Anyone training to be an engineer?

Engineer comes from Latin ingenium (ingenius—the ‘inner genius’ or guiding spirit that each person is born with according to Greek mythology; innate qualities, ability; inborn character).

From this source comes 12th century Old French engin (skill, wit, natural talent, cleverness; trick, deceit, stratagem; war machine). At this time, Latin ingenium also meant a war machine or battering ram. By around 1300, the word engine came to English meaning a mechanical device, especially one used in war; a manner of construction; and skill, craft, innate ability; and, deceitfulness and trickery. A ‘maker of engines’ in ancient Greek was a mekhanopoios—you can see the roots of the word mechanic here.

By the mid-14th century the word enginour (engineer) had evolved from engin (engine) and from 12th century Old French engigneor (engineer, architect, maker of war-engines; schemer). The general sense of an engineer as an inventor or designer is from the early 15th century, and particularly in relation to public works from around 1600. However, the term ‘civil engineer’ does not emerge until the 19th century.

Engineer as a locomotive (i.e., train engine) driver is from 1832.

The verb ‘to engineer’ (to act as an engineer) is from 1818. To engineer, meaning to arrange, contrive, guide or manage via ingenuity, is from 1864. Strangely, around 1300 ‘to engineer’ mean to seduce, trick, deceive, and put to torture.

Engineering, meaning the work done by an engineer, is from 1720. Engineering as a field of study is from 1792. Earlier words included engineership (1640s) and engineery (1793) but these words did not stick in the language.

In short, I have to say that I like the idea that the word engineer comes from the word ingenius!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Engineer comes from Latin ingenium (ingenius—the ‘inner genius’ or guiding spirit that each person is born with according to Greek mythology; innate qualities, ability; inborn character).

From this source comes 12th century Old French engin (skill, wit, natural talent, cleverness; trick, deceit, stratagem; war machine). At this time, Latin ingenium also meant a war machine or battering ram. By around 1300, the word engine came to English meaning a mechanical device, especially one used in war; a manner of construction; and skill, craft, innate ability; and, deceitfulness and trickery. A ‘maker of engines’ in ancient Greek was a mekhanopoios—you can see the roots of the word mechanic here.

By the mid-14th century the word enginour (engineer) had evolved from engin (engine) and from 12th century Old French engigneor (engineer, architect, maker of war-engines; schemer). The general sense of an engineer as an inventor or designer is from the early 15th century, and particularly in relation to public works from around 1600. However, the term ‘civil engineer’ does not emerge until the 19th century.

Engineer as a locomotive (i.e., train engine) driver is from 1832.

The verb ‘to engineer’ (to act as an engineer) is from 1818. To engineer, meaning to arrange, contrive, guide or manage via ingenuity, is from 1864. Strangely, around 1300 ‘to engineer’ mean to seduce, trick, deceive, and put to torture.

Engineering, meaning the work done by an engineer, is from 1720. Engineering as a field of study is from 1792. Earlier words included engineership (1640s) and engineery (1793) but these words did not stick in the language.

In short, I have to say that I like the idea that the word engineer comes from the word ingenius!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on August 24, 2020 19:59

August 23, 2020

T & S Syndrome

Here’s a couple of words related to teacher diseases from the pre-Covid19 world. Hopefully, we may not see them as often as we move into the virtual classrooms and remote learning environments of the ‘new normal’. Nevertheless, I suspect that these new environments will generate their own teacher diseases.

Here’s a couple of words related to teacher diseases from the pre-Covid19 world. Hopefully, we may not see them as often as we move into the virtual classrooms and remote learning environments of the ‘new normal’. Nevertheless, I suspect that these new environments will generate their own teacher diseases.Some diseases, such as the common cold, are transmitted from person to person by bacterium or viruses carried through the air. Some diseases (e.g., cholera) are transmitted from person to person through drinking water containing fecal matter. Some diseases are transmitted sexually. Some diseases are endemic to a particular geography; e.g., the malarias found in hot humid tropical areas.

A couple of these pre-Covid19 diseases, tachydidaxy and stentordidaxy, the so-called ‘teacher diseases’, were often found in classrooms. Sometimes, under the stresses and strains of teaching, teachers fell ill with one or both. In short, we say that such teachers suffered from ‘T & S syndrome’. In many situations, teachers with T & S often infected their students with ennui morbidus. In serious situations, students may even succumb to tonusus or even cursus quittus abruptus.

Tachydidaxy

Tachydidaxy breaks out when a teacher becomes overwhelmed by the amount of information which has to be delivered in a course. The teacher becomes ill with tachydidaxy when, failing to find ways to effectively manage this information, they simply try to deliver it all. This situation is not helped when a college reduces the length of the course or limits the resources available to the teacher. Sometimes new or inexperienced teachers succumb to tachydidaxy as they get to the end of a course and realize that there are still several chapters of the text left to cover.

Tachy- is a Greek prefix meaning fast (e.g., a tachometer measures how fast a vehicle driveshaft revolves). Didaxy and the related word didactics come from the Greek didaktikos meaning teaching. Quite simply, tachydidaxy arises as the teacher talks faster and faster during lessons in an attempt to deliver all the information or to cover the text before the end of the course. Sometimes, tachydidaxy and stentordidaxy are concurrent.

Stentordidaxy

Stentordidaxy is not the result of an external infection (such as tachydidaxy), but is more related to the teacher’s inner state of being, particularly a loss of self-confidence or loss of control in the classroom. Stentordidaxy is often seen in situations of ineffective classroom management.

In Greek legend, Stentor was a Greek herald during the Trojan War. He is described in Homer’s Iliad as having the voice of fifty men. Didaxy and didactics, as described above, mean teaching. Quite simply, stentordidaxy arises as the teacher talks louder and louder while teaching.

In short, a teacher suffering from T & S Syndrome talks faster and faster, louder and louder, in valiant but often futile attempts to cover course material or manage other problematic classroom situations.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on August 23, 2020 20:49

Fink

A colleague asked, “What about the word fink?”

The short answer is that the origins are unknown. It is first seen in English in 1902, possibly from German Fink (a frivolous or dissolute person; an informer). German Fink also meant finch (a common European bird) suggesting perhaps a comparison with ‘stool pigeon’.

Another theory suggests that fink comes from ‘the Pinks’; that is, the private police force known as the Pinkerton agents who, notably, were hired to break up the 1892 Homestead strike: a deadly clash between union workers of the Homestead steel mill who were on strike and the ‘Pinks’ who were hired to break up the strike.

The verb ‘to fink’ comes into American English slang in 1925.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

The short answer is that the origins are unknown. It is first seen in English in 1902, possibly from German Fink (a frivolous or dissolute person; an informer). German Fink also meant finch (a common European bird) suggesting perhaps a comparison with ‘stool pigeon’.

Another theory suggests that fink comes from ‘the Pinks’; that is, the private police force known as the Pinkerton agents who, notably, were hired to break up the 1892 Homestead strike: a deadly clash between union workers of the Homestead steel mill who were on strike and the ‘Pinks’ who were hired to break up the strike.

The verb ‘to fink’ comes into American English slang in 1925.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on August 23, 2020 19:57