Walker Elliott Rowe's Blog, page 6

November 2, 2016

Southern Pacific Review Editorial Services

by

Walker Rowe

I am writing this description of my writing and editing business for the LinkedIn ProFinder Contest.

Southern Pacific Review Editorial Services

I have found that tech businesses have a big need for freelancer writers to write blog posts, white papers, and manuals. This has created a market for tech writers who know computer programming. Tech companies need writers with a tech background so that they can understand and describe their customer’s products.

There are two reasons that tech businesses seek freelancers. First, they usually have a short-term need so do not want to hire a full-time employee. Second, most people, in particular tech people, do not like to write or do not write well. Plus when asked to write something they put that way down on their priority list.

I fix that problem for my tech clients by helping them explain to their prospects and customers what their products and services do.

There are several forums for that. First, a company has their web site. That is usually filled with writing that, while it explains a tech product, is written as sales writing. Then they have a blog section where I write documents that are more technical in nature. Those can be tutorials. It can be news. Or it can be a technical deep dive into the complex details of some algorithm or code.

How LinkedIn Profinder Can Help my Business

LinkedIn is in a good position to help match up freelancers with clients and help clients find the right freelancer, because LinkedIn can cut right through the fraud that is prevalent on the other freelancer sites.

On LinkedIn, you cannot pretend to be someone else. A person builds up their LinkedIn presence over time with work history, recommendations, and contacts.

To put customers and contractors together, LinkedIn Profinder can help me by expanding their concierge system and, in particular, go outside the borders of the USA. The concierge system is where LinkedIn algorithms and persons seek to match freelancers and clients. I have moved outside the USA now. I am an expat American. So that system has stopped sending me recommendations.

The system you have in place now has some one major flaw: it is geographically based. As an internet company you should know that borders do not exist in cyberspace. So it makes no sense for you to recommend freelancers who live in a certain area. I never go visit my clients in person and hardly talk on the phone. We do all our business by email. So what difference does it make if I am just around the corner?

Finally, I am glad that LinkedIn is making small moves to enter the freelance market. This could be a $1 billion business for LinkedIn. But you need to figure out whether you want to allow proposals and provide some kind of search tool. Or do you just want to continue with your concierge service? Either way I am finding the vast majority of my clients outside of LinkedIn. Your service is moving too slowly.

September 28, 2016

Allegations of Police Abuse in Chile blight Carabineros reputation

by

Cameron Ridgway

28 September 2016. Concepción, Chile.

The Carabineros, Chile’s national police force, have long held a reputation as one of the most trusted in Latin America.

That may all be about to change, however. A report published by the Medical College of Chile on Sunday revealed evidence of 101 acts of torture committed by officers between 2011 and 2016.

The college’s Department of Human Rights, which conducted the investigation, defined torture as any deliberate action committed by an officer “with the intention of causing strong physical or mental pain”.

The Revelations

The incidents mentioned in the report took place either during detention or in a police vehicle. Recorded victims were aged between 14 and 74 and came from a variety of social backgrounds.

Torture methods that were found to be used include asphyxiation with plastic bags and waterboarding.

The report also details accusations of violent and abusive behavior, including removing children’s clothes, heavy beatings and attacks on the genitals of prisoners.

Marta Cisterna, from the Chilean Commission on the Observation of Human Rights, revealed that the allegations in the new report related to incidents in Santiago and Providencia and were made both by officers and members of the public.

On the Rise

Eighteen of the reported cases took place in 2011, falling to twelve in the following year. 36 cases reported took place during 2013, making this by far the worst year as the number fell again to 11 in 2014 and 10 in 2015 respectively.

The number of cases this year already looks set to be much higher. To date 21 allegations of police torture have been reported.

In spite of this rise, Karina Soza, a lawyer for the Carabineros, told the Pan Am Post that the public should continue to trust and have confidence in the police. She reiterated that the Carabineros condemned the use of such practices and wanted to put an end to such violent behavior.

Seeking Justice

Cases of Human Rights violations involving the Carabineros are currently dealt with by the military courts, who determine their credibility and decide whether to sentence.

Concerns about this system were raised in August 2011 after then-Sergeant Manuel Millacura was found guilty of causing the death of 16 year old Manuel Gutierrez at a union protest in Santiago after attacking him while trying to disperse the demonstration.

The military court handling the case initially sentenced Millacura to three years and one day in prison. This was later reduced to a 400 days after the court determined that Gutierrez’s death was a result of criminal negligence rather than a willful act of unnecessary violence.

The family of Manuel Gutierrez later unsuccessfully appealed the decision at Chile’s Supreme Court and have since joined a growing number of voices campaigning for reform of Chile’s military justice system.

The Chilean branch of Amnesty International, along with other NGOs and some lawyers, argue that human rights cases involving the Carabineros should be tried by civilian courts instead of the military system to ensure fairness and impartiality.

The UN has also recommended that Chile instigates reform of its military courts. While both the Bachelet government and the military have promised changes, they have not yet been implemented.

For these new revelations to be viewed as being taken seriously by the Chilean government, judicial reform may be just what is needed.

September 15, 2016

Actors Play Asians in Brown (Black) Face

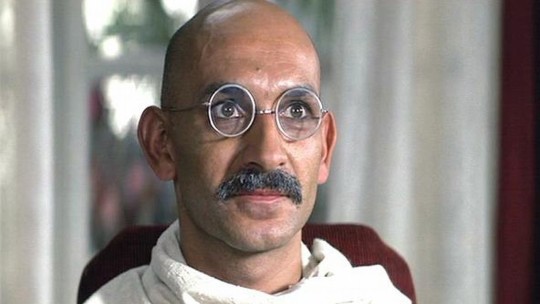

Photo: Ben Kingsley places the Indian Ghandi in brown-face makeup.

By

Walker Rowe

In California there are more Hispanics than whites and there are millions of Asians. But on the wide screens of Hollywood you do not see that multicolored hue as most actors are George Clooney white. The few Asians you see on the big and little screens are usually cast as the stereotypical immigrant. But this situation could be changing. If not today, maybe tomorrow.

Netflix has a new series called “Master of None.” It might be one of the best original Netflix shows out now. That, of course, is hard to say because there is so much good programming on Netflix. Their enormous pile of content has led many of us to indulge in the new addictive habit we now call binge watching where people spend entire days and weekends watching Netflix series from one end to the other.

Doing that would not be a waste of time if you were to watch Master of None. This is because this unique program speaks directly to two issues facing Asians living in America and young Americans of all kinds. These are the challenges young people face when dating and trying to pick a mate and then the added complexity of doing all of that, and handling work, when one is an Asian living in America.

Akash Mati stars as a second generation Indian named Akshay. He is working as an actor in New York City, doing commercials while he looks for work in a sitcom or film. Because Akshay is second generation he does not have a thick Indian accent, which is something that Akshay finds is what TV producers expect and even want.

The whole accent thing is a continual source of irritation because New York casting agents keep asking him if he can play Indian roles with an accent. He does not want to do that. He does not want to be color cast. He just wants to play an American.

The producers tell Akshay that audiences do not want Asians in leading roles because those movies quickly get labelled ethnic. Than then limits their market. And the market for Hollywood is global.

Akshay is put in a difficult situation when a director gives him and a friend roles but the producer needs to kicks one of them off saying they can have one Indian actor but not two. One Indian actor makes the Big Bang Theory. Two turns it into Bollywood.

Much has changed in the USA since the 1920’s when actors painted their face black to portray blacks, the most famous being Al Jolson. That is called blackface. Now it is taboo. Students have been kicked out of different American universities in the past couple of years for doing that at fraternity parties.

But as recently as a 1988 white actor played the lead Indian role, in brownface. That was in “Short Circuit 2.” And this year Hollywood caste the strawberry blonde Emma Stone to play Alison Ng, a character who is ½ Chinese and ¼ Hawaiian. Even in “The Social Network,” a movie about the founding of Facebook, one of the Indians Harvard students was played by an actor who is ½ Chinese and ½ English.

Regarding the Emma Stone film, the director of that movie was criticized for being what CNN called “culturally insensitive.” He said, “Thank you so much for all the impassioned comments regarding the casting of the wonderful Emma Stone in the part of Allison Ng. I have heard your words and your disappointment, and I offer you a heart-felt apology to all who felt this was an odd or misguided casting choice.”

One complaint from the Media Action network was, “It’s so typical for Asian or Pacific Islanders to be rendered invisible in stories that we’re supposed to be in, in places that we live,”

Aziz Ansari talked about all of this in a New York Times article. He explained how when he saw Short Circuit 2 as a kid he thought he could grown up to be an Asian actor too. But then he found out the actor was not Indian at all. He said, “One day in college, I decided to go on the television and film website IMDB to see what happened to the Indian actor from ‘Short Circuit 2.’ Turns out, the Indian guy was a white guy.”

Aziz, whose is a standup comic who has sold out Madison Square Garden, writes with humor of the difficulties of navigating this situation even from the other side, i.e., the role of the director.

He said, “I had to cast an Asian actor for ‘Master of None,’ and it was hard. When you cast a white person, you can get anything you want: ‘You need a white guy with red hair and one arm? Here’s six of ’em!’ But for an Asian character, there were startlingly fewer options, and with each of them, something was off,” like they had no accent.

The lack of Asian actors on Hollywood screens makes having one there noticeable in itself. Such was the case of Sandra Oh, the hospital intern in “Grey’s Anatomy.” And then there was David Carradine, an Irish American who played the lead role in Kung Fu, the legendary 1970’s saga of a Buddhist karate expert and priest who wanders the west teaching people about inner peace and fighting off bad guys. He sort of looks Asian in the series but he has not one drop of Asian blood.

What Asian actors like Aziz want is a world where being Asian in a film is not something that people notice. That is what black people achieved when Bill Cosby played Cliff Huxtable, the non-threatening loveable doctor in “The Cosby Show.” Of course, Bill Cosby is no longer an example that people can cite of an actor who has transcended the color barrier because he faces criminal charges for rape. But he was definitely the first minority actor to transcend the color barrier.

But America will change, and thus what is broadcast around the world, as Asian and other immigrants pour into that country, swelling their ranks. More Asian actors will get leading and supporting roles that do not require them to be karate experts.

You can already some of this in the comedy “Fresh Off the Boat.” That title obviously refers to the Chinese family in that show as being just in from the airport, which they are not. But it sums up succinctly the status of the immigrant as a tax paying resident of the USA but not exactly a part thereof.

In the show, the Chinese father packs up the kids and moves from Washington, DC to Orlando to open the cowboy Cattleman Ranch Steakhouse. Of Florida, the mother says that “The humidity is bad for my hair.” and asks her pre-teen kids “Why do all of your shirts have black people on them?”

But that there is a popular and successful series at all whose principal characters are named Huang is notable in itself.

Pinochet still Casts Shadow over Chile

Note: The photo above taken by Reuters photographer Carlos Vera Mancilla went viral. It shows a girl staring into the face of a policeman. It was taken at the protest this week honoring victims of the dictatorship.

by

Cameron Ridgway

Chile’s democracy is continuing to wrestle with the legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship.

The Legacy of Pinochet

Augusto Pinochet came to power in the 11th September 1973 coup that deposed President Salvador Allende. He ruled Chile as dictator between 1973 and 1990 and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces until 1998.

During this time, Chile’s military and police forces were accused of large scale human rights violations in attempts to hold onto power.

By the end of the dictatorship more than 40,000 people had been victims of torture and kidnapping and over 3,000 had been murdered. Around 1,000 of these murder victims are still unaccounted for.

Modern Day Retribution

As reported by BBC Mundo, seven former Pinochet era military officials were recently sentenced to time in prison by a high court judge, convicted of human rights abuses ranging from torture and kidnapping to murder.

Of the seven sentenced in August, Sergio Benavides (a former army colonel) and Manuel Vega (a former police chief), were sentenced to life imprisonment. A further four officials were sentenced to fifteen years behind bars and one other received a sentence of ten years and one day.

These sentences come at a sensitive time for Chile in light of the recent commemoration of the 43rd anniversary of the coup. An official commemoration was held on September 11th outside the Moneda Palace in Santiago, the presidential seat of power and site of the coup.

Groups supporting the families of the ‘disappeared’ protested outside the ceremony, criticizing the annual ‘celebration’ and demanding greater recognition of the atrocities committed. These demonstrations later turned violent as they marched toward one of Santiago’s main cemeteries.

Human Rights

The issue of human rights has also recently become more prominent in Chilean politics, with appointment of Lorena Fries to the new cabinet position of Subsecretary for Human Rights. A government spokesperson described the role’s goal as searching for justice among the ‘permanent challenges’ posed by Chile’s history.

In practice, this is likely to mean an intensification of efforts to end the ‘pacts of silence’ that many human rights organisations say exist between many former Pinochet officials to prevent their prosecution.

A number of these organizations have recently intensified their investigation into Chile’s ‘disappeared’. Salvador Allende’s daughter, Senator Isabel Allende, recently warned that there was still ‘much more walking’ to be done if justice was ever to be achieved.

A Lavish Punishment?

When convicted, there has been harsh criticism of the generous treatment afforded to prisoners convicted of charges against the regime. While many of these men are now aged 60 or older and increasingly frail, the Punta Peuco prison where many of them are held has been accused of treating them favourably and offering them additional benefits not afforded to other prisoners. It has a tennis court and satellite TV.

The Chilean government, however, recently reaffirmed its view that the treatment of Punta Peuco inmates was the same as in ‘any other jail’ in the country. The Chilean Defence Minister refuted protesters’ calls for its closure, claiming any preferential treatment of prisoners which may have happened in the past has long since ended.

With increasing public interest as more evidence of police, military and political activity during Pinochet era is uncovered, both further prosecutions and demonstrations seem increasingly likely.

September 7, 2016

De Sueños y Canciones: El Abrazo de la Serpiente, un filme de Ciro Guerra

Por

Eduardo Frajman

El trauma causado por la crueldad y la opresión no es nunca individual sino colectivo. Está inextricablemente vinculado a las rupturas políticas que la violencia deja a su paso. Tratar el trauma requiere entonces transformar, sanar, liberar a la sociedad. Pero ¿qué de aquellos casos en que la sociedad misma ha sido aniquilada, en los que la transformación y la liberación son imposibles, en los que el trauma se ha establecido como un accesorio de la realidad, inevitable, inextirpable? Queda entonces sólo la labor del salvamento, recordar la tragedia, la insensibilidad de los perpetradores, el sufrimiento de las víctimas. Queda conservar los nombres de los desaparecidos, resguardar sus creencias, sus costumbres, su experiencia. Queda rescatar la dignidad de lo perdido.

Karamakate, protagonista del extraordinario filme colombiano El Abrazo de la Serpiente, carga sobre sus hombros tal abrumadora responsabilidad. Karamakate se cree único sobreviviente de su pueblo, los Cohiuano del Amazonas. Vive en el corazón de la selva en exilio autoimpuesto, lidiando contra el olvido. ¿Qué ha de hacer esta figura solitaria, este Hombre Omega, para enfrentar al enemigo invencible? Esta es la pregunta fundamental que impulsa la trama del filme: captura a Karamakate en dos encrucijadas cruciales de su vida, divididas por el tiempo pero presentadas en forma paralela. Cada una es catalizada por un viaje que el chamán emprende junto a un hombre blanco. Ambas aventuras siguen esencialmente la misma trayectoria, mas culminan en destinos opuestos.

En 1909, el antropólogo Alemán Theodor Koch-Grunberg (interpretado por Jan Bijvoet) navega el Amazonas y sus tributarios en busca de Karamakate, acompañado de Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), un indígena Bará que ha asimilado las costumbres de los europeos. Karamakate (Nibio Torres) es entonces un hombre en la flor de la vida. Su imponente físico y firme voz exuden vigor e intensidad. Sus emociones estallan sin advertencia: cuando enfadado hace berrinches estridentes, cuando feliz suelta carcajadas estrepitosas. Su presencia es reconocida y respetada por las tribus que lo rodean, dados su vasto conocimiento y sus habilidades medicinales, que le han obtenido el título de “movedor de mundos.” Theodor está enfermo, al borde de la muerte. Los chamanes de la región le han sugerido que Karamakate puede salvarlo con la flor sagrada llamada yakruna. Karamakate inicialmente se rehúsa. Su furia contra los hombres blancos que invadieron su mundo y, sin piedad, lo continúan despojando no conoce límite. Cambia de opinión, sin embargo, cuando Theodor le asegura que los Cohiuano no han desaparecido del todo, y que puede llevar a Karamakate a reunirse con los residuos de su gente.

En 1940, el etnobotánico norteamericano Richard Evans Schultes (Brionne Davis), se topa con Karamakate durante su búsqueda por la yakruna, guiado por los escritos de Theodor. El viejo Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar) es ahora un anciano áspero y endeble. Lo que es peor, las décadas de soledad le han robado la memoria. Traza dibujos sobre las rocas sin entender su significado. Ha perdido la habilidad de preparar las yerbas medicinales. El viejo chamán se considera a si mismo un chullachaqui, un espíritu vacío, sin hogar ni propósito ni esperanza. Su ira se ha desgastado y transformado en desaliento. Se ofrece a servir de guía para Richard, a pesar de haber olvidado la localización de la flor. Richard afirma buscarla por razones puramente académicas. Karamakate, sin embargo, es suficientemente perspicaz para intuir que las intenciones de este nuevo visitante no son tan inocuas.

El Abrazo de la Serpiente es, como lo afirma su director, el colombiano Ciro Guerra, “una historia de dos vidas.” ¿A qué dos vidas se refiere? Por un lado están las vidas de los dos blancos, Theodor y Richard. Ambos han dedicado varios años a aprender los secretos de la selva y la vida de sus comunidades. Conversan con los locales en español y en los idiomas aborígenes, comparten sus costumbres y comprenden sus creencias. Los dos exploradores sufren de la misma aflicción: ninguno de los dos puede soñar. Por el otro lado están las dos vidas de Karamakate, quien debe decidir si es capaz de abandonar su resentimiento hacia los forasteros, aceptarlos como iguales, y transmitirles su sabiduría. La trama entrelaza a estos dos pares de vidas de tal manera que el destino de cada uno es finalmente determinado por Karamakate. Es él, y no los supuestamente superiores extranjeros caucásicos, quien posee el poder del libre albedrío.

Filmado en límpido blanco y negro con un limitado presupuesto de 1.5 millones de dólares, el filme rebosa con autenticidad y originalidad. El guión, escrito por Guerra y Jaques Toulemonde Vidal, dramatiza los escritos de Koch-Grunberg y Evans Schultes mediante la figura ficticia de Karamakate. Guerra expresa admiración por los dos académicos – “Los primeros en humanizar a los indígenas, en entenderlos no como almas en pena que había que salvar, sino como seres llenos de sabiduría,” declara. Su prioridad artística es humanizar a las comunidades indígenas del Amazonas y desmitificar a la jungla, su hogar ancestral: “no quería contar la película de siempre,” dice Guerra, “un blanco que llega a ese mundo y, deslumbrado, la narra desde su visión.” La selva Amazónica no es el infierno ininteligible de Apocalipsis Ahora o Fitzcarraldo. Es un medio ambiente lleno de vida, con el que la audiencia siente una inmediata conexión gracias a la facilidad con que los personajes blancos e indígenas interactúan. Es crucial que Karamakate (en sus dos etapas de vida), Manduca, y el resto de los indígenas son interpretados por actores de la región, muchos de ellos frente a las cámaras por primera vez, y que el equipo de producción buscó trabajar con la colaboración de las comunidades y con una actitud de humilde respeto hacia la selva. “La selva es un mundo contra el que no puedes luchar,” dice Guerra, “que te puede devorar vivo fácilmente. Nosotros asumimos una actitud de respeto, de dejarnos guiar por las comunidades y recibir su protección espiritual. Gracias a eso la selva nos ‘colaboró’ y nos permitió grabar.”

La primera imagen en El Abrazo de la Serpiente es de los árboles y el cielo reflejados en las

tranquilas aguas del río. Los espejos, las reflexiones y las repeticiones recurrirán durante el filme, literalmente en las aguas del Amazonas y sus tributarios, pero también en las similitudes entre los dos viajes, y las parejas que forman diferentes personajes durante el desarrollo de la trama. “Eres dos hombres,” el viejo Karamakate le informará a Richard, y el significado de la declaración es ambiguo: Richard mismo contiene dos aspectos, pero también es la mitad de una simbólica pareja con Theodor. Karamakate es, similarmente, dos hombres, pero también forma una pareja con Manduca. Las culturas europeas y americanas se reflejan y entremezclan, así como lo hacen la realidad y los sueños.

La cámara nos muestra al joven Karamakate, acuclillado, completamente confortable en su entorno. De repente torna la cabeza. Ha detectado algo en la corriente. La cámara lentamente se posiciona de tal manera que observamos la canoa que trae a Theodor y Manduca por sobre el hombro de Karamakate. No queda duda, entonces, que nos está animando a interpretar la acción desde la perspectiva del indígena. Manduca se presenta como un miembro de la tribu Bará. Karamakate recibe esta información desdeñosamente. Los Bará, exclama, se rindieron demasiado fácilmente ante los blancos. “Yo no soy como tú, yo no ayudo a los blancos.” Esto llama nuestra atención a un punto de enorme importancia: nunca hubo una gente del Amazonas con una cultura única, sino muchas, muchas gentes, muchas culturas. La región Amazónica domina un área mayor al de Europa Occidental, y en su apogeo era tan variada y heterogénea como las tierras de los blancos.

Karamakate se da cuenta que Theodor viste un collar Cohiuano. Furioso, interpreta esto como una apropiación de su cultura, un hurto, una depredación más. Theodor le asegura que el collar fue un regalo de uno de los Cohiuano restantes. Karamakate entonces acuerda servir de guía en la búsqueda por la yakruna. Para ayudar a Theodor temporalmente, utiliza una substancia que llama “el semen de Dios.” Karamakate le informa las prohibiciones que han de respetar en su viaje. Si no lo hacen, ni recibirán la colaboración de la selva, ni disfrutarán de los beneficios de la planta sagrada.

La escena cambia. Al ritmo de cantos indígenas, observamos una serpiente emerger de su nido y sumergirse en el agua del río. Ondulantemente se mueve con rapidez hasta encontrar al viejo Karamakate. La cámara nuevamente se coloca sobre el hombro del chamán, que ahora observa el arribo de Richard. El norteamericano lo llama en varios lenguajes indígenas hasta que encuentra el apropiado. “Puedes verme?”, pregunta el viejo Karamakate sorprendido. Richard le dice que busca a la yakruna, una planta que crece sobre los árboles de caucho y aumentan su pureza. “Para eso la quieres?,” indaga Karamakate. Richard le ofrece dinero, sabiendo que este no será aceptado. “Nunca he soñado,” le dice Richard a Karamakate, “ni dormido ni despierto.” Karamakate le responde pensativo: “Una vez soñé con un espíritu blanco que estaba enfermo. La única manera de curarse era aprender a soñar. Pero no pudo.” Está claro que Theodor, cuyos libros guían el camino de Richard, no sobrevivió su aventura. Antes de partir, Richard observa al viejo Karamakate a la orilla del río, acompañado de docenas de mariposas blancas que revolotean a su alrededor. La importancia de esta imagen nos será revelada sólo cuando la trama haya llegado a su culminación.

En ciertos momentos el filme corre el riesgo de caer en desafortunados estereotipos sobre las culturas indígenas. La idea de que los indígenas americanos son diferentes a los europeos por su cercanía a la naturaleza data al menos a los tiempos de Jean Jacques Rousseau y su “noble salvaje,” y ha sido reificada en filmes tan diversos como Danza con Lobos, la versión animada de Pocahontas, Apocalypto, e incluso fantasías espaciales como Avatar. Los sueños, en estas versiones, tienen poderes mágicos y sirven para transformar a estos pueblos en creaturas fantásticas, irreales, y por ende deshumanizadas. La realidad es que la mayor parte de las culturas pre modernas alrededor del mundo utilizaron los sueños como instrumentos para comprender a la realidad. La Biblia está repleta de sueños proféticos y visiones divinas. Lo mismo es cierto en los poemas de Homero, las Vedas hindúes, las Sagas nórdicas. La capacidad de soñar en El Abrazo de la Serpiente no es una habilidad mística y sobrenatural sino simplemente un símbolo de la apertura sicológica a lo nuevo, a lo diferente. Cuando uno de los dos visitantes finalmente aprende a soñar, su única recompensa es ser el nuevo repositorio de la memoria de los Cohiuano.

Nuevamente estamos con Theodor, Manduca, y el joven Karamakate. Los viajeros hacen una parada con una tribu que conoce a Theodor. El europeo entretiene a la tribu con dibujos de animales exóticos, hipopótamos y demás. Les muestra su brújula y otros instrumentos. Con la ayuda de Manduca canta una canción y bufonea con un baile traído desde su tierra. Vemos a Karamakate sentado a un lado, pensativo. Tal vez el extranjero no es tan malo, si está dispuesto a compartir sus experiencias y su cultura tan libre y abiertamente. Desgraciadamente, la visita termina con discordia y rencor. Uno de los miembros de la tribu se apodera de la brújula. Theodor está furioso y demanda su retorno. Le explica a Manduca que no puede dejar el instrumento con la tribu, ya que este puede causar la pérdida de los conocimientos ancestrales de los indígenas. Karamakate no entiende tal reacción. “No puedes prohibirles que aprendan!,” regaña a Theodor. “El conocimiento pertenece a todos los hombres. Pero tú nunca lo entenderás porque eres sólo un blanco!”

Esta escena, aparentemente secundaria a la trama principal, introduce el interrogatorio fundamental de El Abrazo de la Serpiente ¿En qué constituye el conocimiento? ¿De qué manera debe transmitirse? ¿Con qué fines? ¿En qué forma difieren el conocimiento de los blancos y el de los indígenas? La actitud farisaica de Karamakate encubre la dificultad de contestar satisfactoriamente estas preguntas. Karamakate no cree verdaderamente que todos los conocimientos de los blancos son útiles o positivos. En varios momentos, tanto el joven como el viejo Karamakate urgen a sus compañeros de viaje a deshacerse de su equipaje: de sus libros, instrumentos, vestimentas. Ambos se rehúsan. “No puedo tirarlos,” le explica Richard al viejo. “Son necesarios.” Theodor es aun más vehemente: “Estas no son sólo cosas. Son mi conexión con mi familia, con mi gente. Contienen todo lo que he aprendido. Dejarlos atrás es dejarlo todo.” Karamakate responde con desdeño, y decididamente con agresión hacia Manduca, que ha aprendido a vestir y hablar como los europeos, tanto así que escribe las cartas que Theodor le dicta en alemán. Al mismo tiempo, Karamakate duda si debe transmitir su conocimiento a los blancos. En ciertos momentos decide hacerlo, como cuando le explica a Theodor como remar adecuadamente en la canoa. En otros es más reticente, especialmente cuando obs

erva los desechos de las plantaciones de caucho, que han destruido su hogar y esclavizado a su raza.

Entre los despojos de una de estas plantaciones, Karamakate descubre que Theodor y Manduca cargan un arma de fuego. Como es de esperar, responde furiosamente. Después de tirar el rifle a las profundidades del río enfrenta a Theodor: “Todo tu conocimiento lleva a la violencia! No se puede confiar en los blancos.” Rechaza a Manduca como un “caboclo,” un traidor a su gente. El genio de El Abrazo de la Serpiente es que no toma el camino fácil, volviendo las tablas hacia el hombre blanco y tratándolo de salvaje. Theodor no se deja intimidar por el sufrimiento del indígena. “Este es mi conocimiento,” explica. “Tú intentas entender el mundo que te rodea y yo también. Estas son mis palabras. Esta es mi canción. Esto no es muerte. Es vida!” Es aquí, donde las atrocidades del colonialismo son presentadas más claramente, en que ocurre el giro en el carácter del protagonista. No es Theodor el que cambia, sino Karamakate. Mientras Theodor blande su libros frente al chamán, Karamakate reconoce una imagen. “¿De dónde sacaste esto?,” pregunta. “Lo soñé,” responde Theodor. Karamakate, descubriremos poco después, ha tenido el mismo sueño. “Es imposible,” opina Theodor. “Por supuesto que no lo es,” responde el chamán.

Karamakate decide permitirle a Theodor tomar el caapi, una planta que induce alucinaciones. Theodor, sin embargo, no puede soñar ni con la ayuda de la droga. Karamakate, por su parte, recibe una visión del “señor caapi.” Una serpiente ha viajado del cielo con un mandado nefasto. El jaguar, el protector de la selva, advierte a Karamakate que su responsabilidad es proteger a Theodor. A la mañana siguiente, Karamakate se examina a sí mismo en una imagen fotográfica creada por Theodor. Le pregunta a Theodor si la fotografía es su chullachaqui. “Es una memoria,” explica Theodor. “Un momento que ha pasado.” Karamakate es insistente. “Le vas a mostrar mi chullachaqui a los otros blancos?” “Si me lo permites,” responde Theodor. Karamakate asiente. Theodor, que bien sabe que debe canjear algo por el regalo que el chamán le ha dado, intenta darle en collar Cohiuano que viste. “El collar es parte del Cohiuano,” le dice Karamakate. “No se puede intercambiar.” Theodor asiente, satisfecho que el indígena finalmente comienza a aceptarlo como un igual. “Por qué no buscaste al resto de tu gente?,” pregunta Theodor. “Era sólo un niño,” responde Karamakate, pero con vergüenza, reteniendo parte de su historia.

En un claro de la selva, los viajeros encuentran un asentamiento construido por los blancos. Cuando Theodor, Manduca y el joven Karamakate desembarcan, son recibidos por un grupo de niños indígenas vestidos de blanco. El asentamiento ha sido transformado en una misión jesuita. El cura a cargo les explica que busca “rescatar” a los huérfanos de las plantaciones de caucho para enseñarles el camino de Dios y separarlos “de la ignorancia y el canibalismo.” Karamakate revela entonces que él mismo fue raptado por curas misionarios cuando niño, lo que explica su separación del resto de los Cohiuano. Esa noche busca a un grupo de niños para impartirles un poco de conocimiento. “Nunca olviden quiénes son y de dónde vienen,” sentencia. “No permitan que nuestra canción desaparezca.” No es de extrañar que sus intentos culminan en tragedia.

Cuando Richard y el viejo Karamakate se topan con el asentamiento, la situación es

radicalmente diferente. La misión ahora alberga a un culto religioso liderado por un sicótico hombre que se declara el mesías y combina las tradiciones indígenas con el cristianismo. “No son humanos,” concluye el viejo chamán. “Son lo peor de los dos mundos.” Las escenas en este colectividad infernal difieren tonalmente del resto del filme. La tranquilidad de la selva es reemplazada por la histeria y el delirio. Karamakate, que vagamente recuerda su anterior visita al asentamiento, enfrenta a la locura con la culpa del sobreviviente: “Yo debía resguardar el conocimiento de mi gente, pero vinieron los colombianos y me quedé solo. Necesito recordar. Necesito continuar la canción de los Cohiuano.”

Quizás conmovido por el sufrimiento de su compañero, Richard se deshace de todas sus posesiones. Lanza sus libros, sus papeles, sus instrumentos al río. Se queda exclusivamente con una caja. “De esta no puedo deshacerme,” declara. “Entonces muéstramela,” le ordena Karamakate. Richard revela su posesión más valiosa, un viejo tocadiscos. Coloca un disco sobre la tabla giratoria y la música de George Frederic Handel inunda la noche de la selva. Karamakate escucha la extraña música, observa al hombre blanco, al río, a la noche estrellada. “Esta es la música que me conecta a mis ancestros,” le dice Richard. “Esta es mi canción.” “¿De qué habla?,” pregunta Karamakate. “De la creación del mundo.” Karamakate absorbe, reflexiona, y finalmente se reencuentra consigo mismo gracias a la música del hombre blanco. El pasado y el presente se entrelazan. Vemos a Theodor enfermo caminando a tropiezos hacia el río. Vemos a Karamakate, joven y viejo, furioso e indulgente, cerrado y abierto. Su voz se superpone sobre la música.

“Para convertirse en guerrero,” entona, “cada hombre Cohiuano debe dejar todo atrás y adentrarse a la selva, guiado sólo por sus sueños. En ese viaje debe descubrir, en silencio y soledad, quién es verdaderamente. Debe convertirse en un vagabundo de los sueños. Algunos se pierden y no regresan nunca. Los que sí vuelven, están preparados para enfrentar todo lo que venga. ¿Dónde están esos hombres? ¿Dónde están las canciones que las madres le cantaban a sus bebés? ¿Dónde están las historias de los sabios ancianos, los murmullos de amor, las crónicas de batalla? ¿Adónde se han ido?”

Karamakate ha perdido todo. Su trauma no es individual, no es suyo, sino colectivo, de todo su pueblo. Él es simplemente el último receptáculo. Carga consigo el conocimiento, sí, pero también la culpa inaguantable, y la tristeza inescapable. Karamakate no quiere transmitir sus memorias a los forasteros blancos, a los hijos de la cultura que asesino a su pueblo, mas ¿qué otra opción le queda?

Las montañas donde se encuentra la yakruna, “el Taller de los Dioses,” han sido ocupadas por guarniciones militares peruanas y colombianas. Ahí el joven Karamakate encuentra finalmente a los restos de su tribu. Empobrecidos, hambrientos, desesperados, cultivan a la yakruna y se emborrachan con ella. “Comparte la yakruna con nosotros,” invitan al horrorizado Karamakate. “Brindemos por el fin del mundo.” Karamakate no puede soportarlo. Arranca el collar Cohiuano del cuello de Theodor. “No te lo mereces!,” grita. Toma una antorcha y, ante los ojos de Theodor y Manduca, quema todas las flores de yakruna y, con ellas, cualquier posibilidad de enlazar su alma con la de sus visitantes.

La cámara nos muestra los ojos del jaguar. El majestuoso animal rige sobre la selva, se desliza sin esfuerzo alguno entre el follaje. Al llegar a la orilla del río, se encuentra cara a cara con la serpiente. La serpiente es el veneno del odio, la desconfianza, la violencia. La serpiente prefiere que la canción de los Cohiuano desaparezca antes de permitir a los europeos apropiarla. El jaguar discrepa. El jaguar cree en abrir los ojos, en compartir el conocimiento, en cantar en coro. Con un salvaje zarpazo, el felino mata al reptil, y lo arrastra con la boca hacia el olvido.

Richard y el viejo Karamakate han llegado al Taller de los Dioses. Queda únicamente una flor de yakruna. “He destruido el resto,” informa Karamakate. Richard quiere preservar la flor, pero el chamán insiste en crear el brebaje sagrado y servírselo al hombre blanco. “Debes seguir el mensaje de tu canción.” “Es sólo un cuento,” protesta Richard. “No,” le informa el chamán, “es un sueño.” “Soy un hombre de ciencia, no puedo guiarme por sueños.” Pero Karamakate insiste: “Los sueños son más reales que la realidad. Escucha la canción de tus ancestros. Ella te enseñará el camino.” Karamakate intenta explicar lo que él mismo ha comprendido. No es cuál canción lo que importa, sino a quién pertenece, si es auténtica, si toca el alma. “Esta es la última yakruna del mundo,” informa Karamakate. “Debes hacerte uno con ella. Es mi regalo.”

Karamakate prepara la poción. Prepara a Richard apropiadamente. Vemos finalmente la realidad desde la perspectiva del hombre blanco, que se ha hecho uno con los Cohiuano. La visión transciende el blanco y negro de la realidad y nos ofrece los colores de los sueños. Al despertar, Richard encuentra que Karamakate ha desaparecido. En su busca llega a la orilla del río, donde su cuerpo es rodeado por innumerables mariposas blancas.

Nominado al Oscar como mejor filme extranjero, y ganador de docenas de premios en Europa y América Latina, El Abrazo de la Serpiente ha sido extensamente alabado por críticos de cine, activistas, académicos, y comunidades indígenas de la región amazónica. Gran parte de estos encomios se ha concentrado en su función como testigo de las depredaciones del colonialismo europeo contra las civilizaciones aborígenes de las Américas, de la insaciable codicia de los invasores blancos por materias primas (notablemente el caucho), del genocidio físico y cultural. Pero El Abrazo de la Serpiente no es simplemente un catálogo de atrocidades ni un mea culpa buscando la expiación. Guerra ha creado una historia apasionante e inspiradora, absolutamente novedosa y, ahora que existe, enteramente indispensable. Su esencia dramática no está en el rechazo de las depredaciones del colonialismo o el capitalismo. El Abrazo de la Serpiente trata a estos fenómenos de la misma forma indirecta y oblicua con que La Decisión de Sophie trata con la Segunda Guerra Mundial y el Holocausto. En lugar de lanzar protestas vociferantes contra realidades establecidas e ineludibles, hurgan cuidadosamente entre las ruinas, en busca de la humanidad que permanece.

Welcoming the British to Concepción, Chile

by

Cameron Ridgway

photo by Hozdiamant, under Creative Commons License

Concepción, Chile. 7 September 2016.

A taste of life as a ‘penquista:’

Concepción, Chile: a city I still don’t quite understand despite having lived here for just over a month.

As an exchange student from the UK, I had always expected that Chile was going to be different. But I could not have envisaged some of the quirks I’ve come across during my time here.

Some things never change, though. The weather, for example, has proven to be just us much of a talking point as back home. I’ve heard the nickname ‘Tropiconce’ mentioned on more than one occasion, and with good reason.

Currently, at the end of winter, the extremes seem to vary between ridiculously heavy rain and moderate sunshine, exemplified by my having to run for a taxi on arrival in what can only be described as monsoon weather.

The weather is not the only turbulent part of living here. In a city I have heard nicknamed the ‘education capital of Chile,’ with a number of public and private universities, the ongoing student protests over the issue of educational reform have made for an equally changeable atmosphere.

With regular cancellation of classes and hastily organized public demonstrations par for the course, this level of disruption is simply now how things are. Walk across the rest of the city and you see obvious signs of support, such as buildings with surprisingly artistic protest slogans or murals painted on the outside.

More than three weeks into term, classes have still not started in faculties that remain occupied by protesters. Recent agreements between some universities and student protest groups are likely to quell this by bringing representatives from both sides together to discuss issues floated by the student movement.

Therefore, in the short term at least, most academic activity is likely to return to normal. Disruption will be at a minimum. Uncertainty does remain, however, over how likely it is that a favorable compromise will be reached. Having seen some of the marches, I’m not filled with confidence.

Onward to Britain

I also seem to find myself discussing the less polemic issue of British politics with Chileans, a topic that no Briton really wants to discuss in depth at home after the controversial 23rd June EU referendum result. Whether I’m asked my own stance, or why the UK voted the way it did, I must have explained something on the topic to nearly every Chilean in the nation.

Like some analyst of British political affairs, I’ve fielded questions in both English and Spanish ranging from a simple ‘why?’ to ‘what do you think?’ to ‘what the hell happens next?’ So much for those who joked that I have the respite of escaping to South America just as UK domestic politics got nasty.

The Dangers of Fast Food

On a lighter note, Chilean fast food is a cheap and cheerful sure-fire way to get fed. For reasons of time, and lack of a full kitchen in the temporary hostel accommodation in which I was initially living, my experience with Chilean cuisine began with the numerous sandwich shops that can be found in nearly every corner of the city.

A ‘Churrasco Italiano’, filled with grilled meat and copious quantities of tomato, avocado purée (a common component of nearly all Chilean fast food) and mayonnaise is nothing more than a recipe for spilling it all out. So is pretty much anything containing avocado purée for that matter—an art yet to be mastered as to how to hold it together.

That’s if you don’t get run over on your way to buying it. A wise warning for anyone heading to a large Chilean city is to completely disregard any indication given by the traffic signals. Rely on your own sense of caution.

For reasons I cannot quite fathom, any traffic turning into a road where there is a pedestrian crossing at the junction will continue regardless of who has right of way according to the signals. To sum up, even if you are walking across a road on a green light you still have a fairly high probability of being mowed down.

Chile, as I’m quickly beginning to understand, is a country that both astounds and perplexes at the same time. While any advice you’re given is useful, take it with a pinch of salt, as nothing is ever as expected.

July 12, 2016

Proust, in the Treehouse, With a Deadly Kiss

Proust, int the Treehouse, With a Deadly Kiss

by Willem MyraThumbnail illustration by Rene Castro… while on Wednesdays I’d see her by the phone booth down the street, reading this or that. Reading Carver or Highsmith or Keret. She’d just stand there, on the curb, impervious to passersby, her bony hands holding the book and her attentive eyes plucking the pollen out of it. It wasn’t her looks that had caught my interest—although, admittedly, she was attractive in her own twisted way—nor her questionable reading place choices, but rather the trekking backpack that accompanied her in this world and the other. Bulky, squared, overstuffed with mystery. Whenever I thought about it I’d imagine it carried the same rubbery smell of the insides of a car left to roast in the sun during summer, when the Eternal City is plagued by sultry temperatures. The backpack wasn’t just cumbersome but heavy too, and the girl, hunched over because of it, appeared tinier than she was, fragile, child-like even. Yet, her standing there for six or seven hours every Wednesday, just standing and reading and greeting those who said hi and helping those who more or less implicitly asked for her services, all this without even breaking a sweat or lamenting back pains, well, I mean… wow. When did they stop making people like that?

Name’s Mona, an acquaintance of mine told me. Twenty-seven years old. Born in Tripoli. Libra. She speaks three languages, none of which of any real utility, if you ask me, and is a hopeless teetotaler.

One day I approached her like an old friend would and asked if she was busy. Not particularly, she said, closing her book. So off we went.

Skipping introductions, we walked quickly and silently to the train station, where I bought tickets for the both of us. We waited a couple minutes, her reading, me people watching, till we were able to board the eleven-thirty am train leaving Rome.

She didn’t ask where we were going. She didn’t say a thing, to be honest. And seeing I myself wasn’t much of a talkative fellow, at least not at such early hours, she stuck to her book. Today it was the Israeli writer’s memoir.

We sat facing each other, the trekking backpack resting on the seat adjacent to hers. I pretended to look at the other passengers while I studied her out of the corner of my eye. She was wearing worn jeans and a light-purple fluffy pullover. Heavy-looking winter boots kept her anchored to the ground. She was taller than me, her legs long and thin like those of a spider. She wasn’t skinnier, though. Had curly hair coming down to her shoulders. Skin like wet sand. She smelled of red Sicily oranges, the ones with their bitter juice and their fish-guts-resembling pulp. When we had gotten on the train she’d taken off her sunglasses, so now I was able to make out the shape and color of her eyes. They were narrow and sunken. Fierce. Their hue reminding me of the liquid filling up the cryogenic tubes in those ’80s sci-fi movies.

You’re got really black hair, she said all of a sudden, which startled me for I thought I was the one doing the studying here. The kind of black I’ve never seen in men before.

Suppose I should’ve said something or at least I should’ve nodded my head in acknowledgment. Instead I kept quiet.

Outside the window, brick houses made way to wooden cabins which made way to spare, tall naked trees which in turn made way to a seemingly endless hill populated by sheep. The sheep seemed happy with their lives.

From a side pocket of the backpack, Mona took out pen and paper. She doodled for a while, the tip of her white-ish tongue sticking out between her lips. When she was done, she showed me her artwork. See this? she said. This is what you look like.

I thought, Yeah, sure, we’ve invented mirrors so I do know what I look like, thank you very freaking much.

I said, Huh, interesting.

This is how you look, she continued, with the unruly hair and the pointy beard and that emaciated body of yours covered in dark clothes.

Okay, I said, you’ve x-rayed me enough.

Has anybody ever told you?

What’s that?

That you, you—Remember that cartoon, when you were a kid? On Cartoon Network.

Which one?

Courage the Dog Who’s A Coward or something along that line.

Barely.

There. You look like you could’ve been a one-time villain on that show. You’d have scared the shit out of Eustace.

Easy with the compliments, woman, I might turn red.

She giggled and I took advantage of her good mood to ask if I could keep the portrait. She handed me the piece of paper, which I folded thrice and had the pocket of my trousers devour.

For the rest of the journey neither of us said a word. We got off the train at the fourth depot, my hometown. I hadn’t been there in over three years. The graffiti now vandalizing the station looked beyond clichéd—nicknames the writers had given themselves; four-letter swear words ’cause they’re cool; Fascist slogans and symbols. The air felt spoiled. The city a couple sizes too small for me. I already wanted to go back to Rome.

You mind walking a little? I asked Mona.

Are you kidding me? she replied with a smile. I could take you to the top of the Himalayas and still be able to run a 5K.

We crossed the city in under forty minutes, our feet going tip, tap, tip, tap with a rhythmic musicality that made the melancholy less oppressive. We walked past downtown, past the building I had spent most of my childhood in—twice I had to stop myself from taking a peek at the second-story window of the apartment Ma, Pa, and I used to inhabit, both physically and mentally—past my high school, past all the corners I had a memory cocoon still attached to, just waiting to be set free and revived. We stopped before we could see the traffic roundabout leading to the suburbs.

We sat on the curb in the parking lot of an abandoned mall. At the far end of the parking lot: windshield glass, cig butts, the dark skeleton of a burnt caravan. The mall: if this was a comic book, the artist would have drawn it covered in cobwebs.

I was out of breath; Mona still fresh as a daisy.

Why did I bring you here? I whispered. I genuinely have no idea.

You don’t?

Cross my heart.

Palahniuk says… she stopped short. I too felt uneasy repeating aloud thoughts that had not originated within my mind, even when I did hold them true. Palahniuk says, she began anew, that we are a different person to everybody we meet. Well, I’m sure he’s not the only one saying it. Point being. Maybe you brought me here because you saw in me the person you needed to visit this place with.

Please, I went. Don’t you start with the cheesy BS.

In front of us there was a modest playground. Swing, monkey bars, merry-go-round, slide, and one headless parrot-shaped spring rider. Once populated by kids, now the playground was deserted, the grass thigh-deep and hay-colored, the earth around the swing littered with beer cans and napkins and plastic bags. A treehouse sat at the exact center of the plot. Seven stairs—seven twenty-centimeters-long wooden planks precariously nailed to the trunk of the tree—led up to it. The way it worked is you, child, climbed those stairs, got inside the treehouse and then, exiting through the frameless window, let your bum go down the curving slide till you finally dropped into the sandbox. While the slide itself was now covered in writing—insults and phone numbers of allegedly easy girls—the treehouse had been spared by the degrading aura that had chewed up and spat out the rest of the playground.

What a depressing shithole, I said. You know, first time I ever kissed a girl… I pointed at the treehouse. Happened right there.

Mona turned to look me in the eye. Said nothing. Did nothing.

She was my girlfriend of two months at the time. First girlfriend. God, I was so awkward, and not in a cute way. We’d hold hands for hours to no end, but as soon as I made eye contact, that was it. I’d lose my mind. Shit. I was so… shy and, and filled with insecurities. She was older than me. Sixteen against my fourteen. Had had previous relationships. Had expectations. I had fantasies at best, theories of how things should have played out.

Days went by and I couldn’t bring myself to kiss her. I didn’t know how. I was terrorized by the thought of me kissing her the wrong way and disappointing her. Enraging her. What if she told the whole school what a pansy I was? What if she spoke with all the girls in the world and persuaded them somehow to ignore me forever? What if they agreed?

That’s silly, said Mona, her voice low.

I was a kid. I was dumb. Anyway, one day one of her girlfriends texts me out of nowhere. I didn’t even know she had my phone number. What the fuck is taking you so long, dipshit? She’s getting old waiting on your ass. I had to do something. So one Friday I brought her here. This was the farthest we could get on foot from both my home and school. It was late afternoon. Mid-November. The sun had set, meaning there were no kids, no parents, around. We worked the swing and the merry-go-round and all the other distractions, and we talked and we shared horny looks and we both hoped it would be the other one to make the first move. Eventually we ended up inside the treehouse, entwined together. Her head on my chest. My right arm, numb by now, stuck underneath her body. Stars were shining in the chunk of sky we could see through the window. It was the perfect poetic setup every girl dreams of. So I man’d up, closed my eyes, and finally kissed her. Our lips pressed together, the sound of her heartbeat, her cherry perfume and slight nervousness-caused sweat—it all conspired together to send me back in time. There I was, nine and carefree. I remembered how unrestricted I used to be back then. How I’d run around town pretending to be Arale, how I’d go with the other kids to steal mulberries from the school backyard, how, after a long day of playing soldiers we’d treat ourselves to some vanilla ice cream from this shop we always had to go through an endless queue to buy anything from. When did that kind of freedom stop being the standard for me? I remember questioning myself that Friday night as the stars shone their dying light on us.

So once the emotionally-loaded time-travel came to an end so did the kiss. I looked at her, feeling oh so proud of myself. I’m glad you did that, she said. The next day, when we met by pure accident while I was doing some errands, she pulled me by the shirt and stuck her tongue in my mouth. It felt so out of place and… gross? Well, one week later we were fucking for the first time, and a few days after that I was gifting her a ring, a real one, gold and Swarovski and all that. It had cost me all my savings, plus I had to borrow some money from Dad. But it was worth it. At the time, it was worth it.

And now? asked Mona, breaking her silence. Is it still worth it now?

Is anything you’ve ever done worth it, in hindsight?

Yeah, most of it.

Lucky girl.

What’s done is done, no need paining yourself over something you can no longer change. If I made mistakes, I try to amend to them. If I can’t, for a reason or another, then I’m at peace with myself knowing that I did all I could to turn into someone who will not be foolish enough to recreate that same mistake twice. Past me tripped and hurt her ankle. Present me learned how to walk straight. She’s a different person.

Panta rei and all that shit.

And all that shit, Mona repeated with a beat.

But I suppose you are right. What’s done is done. I know that. Still, sometimes I can’t help it but be saddened by remembering certain things.

Like your first girlfriend?

Like my first girlfriend.

So, how did she break your heart?

She didn’t. That’s the point.

You wanted her to?

Hell no. Although it is easier to deal with pain than with doubt.

What’s that supposed to mean? What happened between the two of you?

I shrugged. Nothing happened. Not between us. The relationship lasted—what? Eight, nine months? Then at some point we both agreed it was best to go separate ways. I know that’s what the breakupee says and not the breakupper. But it’s true. It was a mutual decision. Our chemistry had run its course. We needed to see other people.

A handshake, a smile, and the deal is over, jokingly said Mona.

Precisely. Wham, bam, thank you ma’am. So years pass by. I graduate from high school. I move to Rome to go to university. New place, new friends, new girls. Everything’s going fine. Then one day I meet this old classmate, Nicky. We have lunch together and reminisce about the old times. And that’s when it hits me. Oh, by the way, did I tell you about your ex? Nicky says. I say, No, what happened? Is she okay? I wish she wasn’t, Nicky says. Turns out the sweet girl I’d departed from had morphed into something akin to a devil. Listen here. The guy she slept with after we were done cheated on her. So what did she do? She went to the police. She was seventeen; he was nineteen. He’s lucky he only got two years in Rebibbia. There’s more. My ex—she persuaded her baby sister to have unprotected sex. The sister got knocked up, had to say goodbye to her dreams of going to university and is now a single momma working two shitty jobs.

Doesn’t seem like the sharpest tool in the box.

Granted, the lil sis is at fault too. But maybe without my ex’s push… And that’s not all. My ex did settle down after a while. Married this guy who had inherited a small family-run business in town. He pays for her studies while she’s in Rome, pretending to go to university. Instead, she cheats on him. I know it sounds soap opera-ish. I didn’t believe it myself. Then I was shown the texts she’d sent Nicky to brag about it, and pictures of the affair. One more story then I swear I’m done. My ex and Nicky—they were friends. Best of friends, actually. That is until Nicky found out my ex had been frequently stealing stuff from her apartment, one little item at a time. First a book, then a blouse, then a necklace. And so on. When Nicky confronted her, my ex jumped into her own car, ran away, unfriended her on Facebook, and started these rumors that Nicky was jealous of her and tried to seduce her husband.

Boy, she sounds like a riot.

She sounds like a hurricane coming straight toward you while you’re handcuffed in the back of a car without a wheel.

Good thing you didn’t experience this side of her.

Yeah. Well… Yeah. I didn’t experience it first hand, but…I don’t get it, you know? How did she go from the girl I loved to whatever excuse of a decent human she is now?

Mona shrugged, the backpack hiccupping up and down.

I whispered, I bothers me. She was my first—everything. She’ll live forever etched into my memory and I’m not sure she deserves it, you know?

I got a new job offer, I said after a while, like I was sharing the good news with my family. Better company, more money. Nicer area. I’m starting next week. Only problem being, the new office is in EUR and every morning on the way in, I’ll have to walk past this kindergarten nearby. And inside the kindergarten’s front yard, right where everybody can see it, there’s a treehouse not dissimilar from this one.

I pointed at it. I pointed and pointed and pointed.

I’ll see it every goddamned day when I go to work and when I return home. And every time, those four wooden walls will work their magic on me. Only instead of reliving the novelty and excitement of my first kiss, I’ll instead think about the current state of my ex’s morality, and about whether or not I am responsible for her abrupt change. And it saddens me. It saddens me that the present—not even my present, but someone else’s—can affect my past. Ruin it. Time’s a circle that fucks you backwards.

A lorry parked not fifty meters from us. The driver got out, checked the tires, had a cigarette, ate a sandwich, had another cigarette. Then the lorry drove away.

Mona said nothing for a long time. Then:

Say, do you always talk so much about your ex on the first date?

This is not a date, I said, sure of my words. Is this a date?

A smile flashed on her face. She rocketed up, offered me the palm of her hand.

Let’s go, she said.

Where?

What kind of question is that? To exorcise this memory of yours.

She led the way to the playground. The tall grass bent sideways to let her pass. We stepped over a Coke can, a purple lighter, an old phone. She took off the backpack, leaving it by the base of the tree. Inside the narrow treehouse, she pushed me into a corner, bit me on the neck, sucked on my earlobes.

This, she said unbuckling my belt, reminds me of one of Keret’s short stories.

#As I was about to climax she reached inside my brain and got a hold of something. When she pulled, I noticed a Smurf-sized Proust in her hands. He was casting scared glances all over the place, trying to escape. He scratched and bit Mona’s fingers, but she didn’t let go. I will not let go, she said, gently. Get over it. Proust tried to put on a fight, then remembered he wasn’t much of a fighter, so instead he adjusted his glasses—he wore oblong smudged glasses now—and put on a resigned look. Good boy, Mona said. She kissed Proust on the side of the head—her lips bigger than his brow—and showed him to his new home inside her big black trekking backpack.

#When we were done, I thanked her and she slapped me, saying she wasn’t an aunt and that she did what she did not because she’d felt obliged but because she had wanted to. Then she started giggling, and since her giggles were cute and contagious, I started laughing too. Soon the whole treehouse was but one big laughter.

Afterward I rolled a joint, which we passed back and forth like we were playing hot potato, until eventually I took a one-, two-, three-, four-, five-, six-, seven-second long puff and exhaled smoke from every hole in my body. An ant was crawling along the treehouse pavement, carrying some white pear-shaped stuff on its back.

Hi, I said.

The ant stopped, briefly, and I hoped it’d look up at me and greet me in an elegant manner, like, Good afternoon, sir. Fancy weather, wouldn’t you agree?

But the ant said nothing, so I put out the joint on its head, picturing it screaming Noooooooooooo! as its little, powerless body instantly turned to ashes.

#Whiffs of yesteryears.

That’s what memories are anyway.

Faded whiffs of things you might believe you recognize, but you don’t. For all you can find is the odor, and no matter how much you try to follow it back to its source, sooner or later you realize a source does not exist. Not anymore.

#I waited for someone to walk by the mall and when this happened, I waved at him and asked him if he could come closer please, just for a second. It was a teenage boy with neckband headphones. He glanced at me and Mona, both still resting inside the treehouse.

Make me a favor, would you? I asked him. From the wallet I took out fifty Euros, handed them to him. Get us a pizza, please? A big one, from over there. I pointed out a pizzeria two blocks down. The change is all yours.

The teenager did as he was told, twenty minutes later he was bringing us our pizza alla diavola.

It cost thirteen-fifty, he said.

Okay.

Are you sure about the change, sir?

I winked at him. Go have some fun, man. Don’t worry.

He thanked me a couple of times and then disappeared behind the abandoned mall.

Mona and I ate pizza for the entire afternoon, drinking red wine and warm beer from her backpack. We shared stories about our past and dreams regarding our futures. When the sun went down and the moon, half hidden by the clouds, came by to say hi, we soaked the insides and the outsides of the treehouse in gasoline—Mona had a copious amount of in her godly backpack—and lit it on fire. We watched as the flames reached to the sky, and we smiled to each other and we had some more beer. Then we took the train back to Rome, where we went our separate ways and never again crossed paths. Or at least that’s how the story goes. Truth be told, I’d see her from afar every so often. For instance: on Mondays I’d see her in front of the La Rinascente, voluntarily sign spinning to attract people to buy roasted chestnuts from this seventy-something unemployed man sitting on the curb, on Tuesdays I’d catch a glimpse of her walking to the kindergarten surrounded by six or seven kid-sized Prousts, while on Wednesdays…

Author Bio

Willem Myra, 24, lives on a satellite of a city gravitating around Rome, Italy. He’s only recently started writing in English, but he’s getting there one misspelled word at a time. When he’s not procrastinating, he tries his best to earn that BA in media studies.

July 1, 2016

Student Protests in Chile come back. Why is there so much destruction?

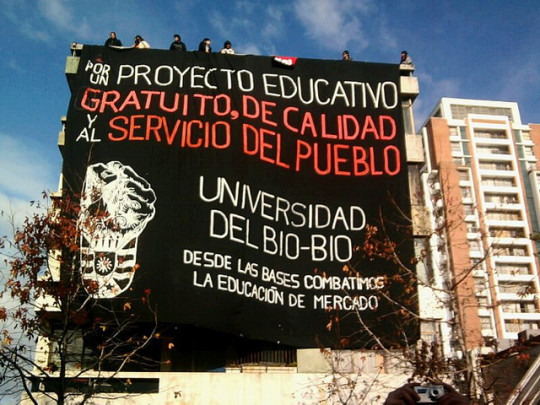

Photo “Chile movimiento estudiantil marcha universidad de Concepcion” by Carol Crisosto Cadiz. It reads “For an free, quality education serving the town.” Though from 2011, it shows what the students demanded then, and what they are still demanding now.

30 June 2016. Santiago, Chile. In this article we explain that student protesters in Chile, in particular high school students, have gone far beyond peaceful protests to outright lawlessness and violence. This increase in violence, disregard for the law, and the adoption of destructive tactics has probably set back the momentum for educational reform more than enhanced it.

In 2011, university and high school Chilean students marched in the streets demand education reform. They are still marching after being relatively quiet for a couple of years. But this time what the students want isn’t clear, since a large portion of what they want has already been passed into law and many of their student leaders have been elected to the Chilean congress.

The Road to Education Reform

Prior to the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, university and grammar school education was free. But Pinochet was a fanatical capitalist who, having just kicked out a communist government, turned over economic planning to economists from The University of Chicago and their Chilean followers. One result was education was turned over to private businesses, for the most part. What emerged for grammar schools was three types: public, subsidized, and private, with parents paying tuition at all three. Even so-called public universities in Chile are profit-making entities. Now students want the return of free public education.

Many of the protests ceased in 2014, with the election of student leaders Camila Vallejo, Giorgio Jackson, and Gabriel Boric to the Chilean congress. Vallejo was a spokesperson for the University of Chile Student Federation (FECH) and led many of the protests in 2011. Jackson and Boric were also members of FECH. Students hoped that their places in Congress would encourage discussion of education reform.

Around the same time, Michelle Bachelet was re-elected president. Given the surge in student protests under President Piñera, Bachelet put education reform at the top of her list of campaign promises. Bachelet, who had already served as president from 2006 to 2010, faced large student protests too, known as the “penguin protests.”

So she promised to bring changes to education if she were elected.

Thus far, Bachelet has succeeded in altering Chilean education, but not to the degree that she or the students wanted. The sharp decline in the price of copper, Chile’s major export, is one factor that allowed the right-wing, who opposes these reforms, to slow down these reforms by saying the country cannot afford it.

In May of last year, Bachelet passed the Ley de Inclusión Escolar (School Inclusion Law). The law included major changes for grammar schools, like no more copayments at schools that were public and free in name only. Bachelet said that as of March, 240,000 students did not have to pay enrollment and tuition fees.

The law also makes illegal the discriminatory selection of students for entry into school. That is to say, students will not have to provide economic, social or academic background information in order to apply for a state-funded school, nor will they have to take a selection test. The purpose of this is to make sure students are not being discriminated against when the school selects which students will attend it. If a school has vacancies, it will have to accept all students who apply. However, when a school doesn’t have enough openings for all the students who apply, a random selection method will be used to avoid discrimination.

After getting her grammar school bill through the congress, Bachelet has finally put forth her proposals for changes in higher education. The Ley de Educación Superior (The Law of Higher Education) seeks to make university education free. As a stop-gap measure laws have already been passed to do that for a small portion of the public.

As we explained a couple months ago, tuition is currently free for those students who are in the bottom 60% of family incomes in the country. But there is a bit of subterfuge here. That number does not mean 60% of students do not pay tuition. It sounds like the intent was to apply that to 60% of all students. In fact, it means given the entirety of the student population, free tuition is given to only those students who come from the lowest 60% of socioeconomic classes. Obviously that number is a lot lower than 60% of all students, since the poor are much less likely to apply to college than the middle and upper classes.

The current bill would also provide quality control for education and changes to the current public education system.

In order to ensure the students are getting the quality of education they need, Bachelet proposed that the National Accreditation Commission be transformed into a Council for the Quality of Higher Education. The Council would award accreditation to schools that meet a certain quality requirement. That quality requirement would be established in a known criteria created by the Council.

With regard to the public education system, Bachelet hopes to create a National System of Public Education so that the quality of an educational institution doesn’t depend upon the finances and capabilities of an individual municipality. We already reported on an OECD study that describes the dismal state of Chile’s grammar schools.

Yet despite the fact that Congress is currently addressing this reform bill, students are still protesting. They take to the streets beating drums, carrying signs that say “no more profits,” and physically seizing schools.

Students Occupying and Vandalizing Grammar Schools

El Mercurio published an article on June 1st that declared 17 grammar schools in toma. The Spanish verb for “to take,” toma is used to describe how student protesters are occupying their schools. They actually move in and take over the schools, lock them down, and prohibit teachers and other students from entering, thus stopping education of any kind altogether.

One of the major grammar schools that seems to be in perpetual toma is the Instituto Nacional, the top public school in the country. Students from there who have sought to enroll elsewhere in order not to ruin their education have sometimes been turned away by private schools who say, “We don’t want any radicals here.”

This school, which they call a flagship, was occupied by the students for 22 days before the Carabineros, the Chilean police force, kicked them out. Students threw molotov cocktails and paint bombs at them. After the Carabineros removed them, the students moved right back in.

This is fairly remarkable behavior for students who are attending the nation’s top school, from which have graduated several former presidents.

But the students do not stop at taking over the schools. They have also destroyed the interior of buildings and stolen computers and other equipment.

Pictures show the inside of the Instituto Nacional covered in graffiti. Plus, the Municipality of Santiago has received reports of extensive damage in 11 of the occupied establishments. In the school Darío Salas, for example, there were fumes of a strange gas found. Likewise, in another flagship school, Internado Nacional Barros Arana, the damage was found to be around $400,000 Chilean pesos ($600,000 US dollars).

The students do not even limit their destruction to educational institutions. At the end of May, a group of masked protesters burned a pharmacy and supermarket in the name of education reform, resulting in the death of a policeman. In another instance, members of the Confederation of Chilean Students (CONFECH), burned a church and destroyed a figure of Christ. That was shocking in a country where the Catholic Church is such a presence that abortion is not permitted under any circumstance and divorce was only made legal in 2004.

The metropolitan manager of Santiago, David Morales, said that he could not remember a student demonstration with a higher level of violence. The mayor of Santiago, Carolina Toha, also commented, calling the student groups demonstrating “ultra small and ultra violent.”

When asked to say something regarding the protests, President Bachelet noted that Chile needs a youth committed to public affairs, but their criticism needs to be constructive, not destructive. Director of Municipal Education Mónica Espina expressed a similar view regarding the destructive actions of the students, saying that “the student movement is being used by certain sectors to destroy public schools.”

The Demands of the Students

The students’ actions have left the Chilean people asking one question: why?

With some of Bachelet’s changes already in place, and other reform being discussed at the moment, the country is left wondering what more the students are hoping for.

When asked by La Tercera, the president of the student center at the Instituto Nacional, Roberto Zambrano, said that the students need to be activists once more, and that they could not allow negligence on the part of the education reform movement. But to what is he referring? La Nacion reports that he petitioned for universal free education and for “profit to leave the market.”

A young boy from the grammar school Liceo Eduardo de La Barra de Valparaíso also explained. He said that grammar schools in Chile are funded based on the student attendance, which he says leaves schools without enough money to pay for school supplies and the school infrastructure, among other things. He said that students want to set up a baseline funding that doesn’t depend on the number of students in attendance.

Journalist Alejandra Valle, whose son was involved in one of the protests, also tried to articulate the viewpoints of the students. She argued that the young people want to improve not just the funding of education, but also the quality of education, like improving teaching methods so that students would be able to think critically.

The Domino Effects of the Protest

Whatever the students may want, the protests have led to another problem unrelated to education reform: interlopers using the protests to loot and wreak havoc.

Delinquents and other members of the Chilean lumpen are taking advantage of the chaos caused by the student movement to carry out small lootings and acts of destruction, reports El Pais.

In fact, the aforementioned CONFECH students who vandalized the church and stole a Christ figure may not even have been students at all. While CONFECH students were marching nearby the church to advocate for education reform, the youths who burned the church could actually have been part of the lumpen. These youths, who are known as encachupados in Spanish because they were wearing hoods over their heads, were denounced by José Corona, a member of the National Secondary School Coordination (CONES). He said that the organization didn’t want any more encachupados involved their protests.

This involvement of outsiders in the protest further extends the damage being done to Chilean communities because of the destructive nature of the student movement.

The question remains if Bachelet’s second wave of reform will pass. And if it does, if it will do anything to quell the student rage that is resulting in destruction in Chilean grammar schools.

June 13, 2016

Job Turnover in Chile Highest of any OECD Country

photo “Construcción” by Alvaro Olivares

13 June 2016. Santiago, Chile. On Friday, La Tercera released an article saying that job turnover in Chile is higher than in any nation in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The information comes from an analysis of job turnover in the most recent Monetary Politics Report, published in June.

The Findings of the Report

The report found that the average percentage of turnover in Chilean jobs between 2005-2014 was 37%. This percentage is higher than any of the other 24 countries studied in the report.

However, the study showed that job turnover varied based on the type of job. For instance, the categories with the highest turnover in Chile were construction (55%), agriculture (42.8%), and financial services (40.9%). This is unsurprising given that these jobs are often based on contracts of a fixed time period, or, in the case of agriculture, based on weather throughout the year.

Meanwhile, jobs in the public service sector and in the mining industry showed the least amount of turnover. Public service jobs had a turnover percentage of 21.8%, and mining jobs had a turnover of 26.1%.

The statistics also showed that bigger companies had a lower percentage of job turnover than small companies. Experts attribute this to bigger companies having more benefits, such as bonuses. Similarly, companies that pay more tend to have fewer turnovers than jobs with lower salaries.