Walker Elliott Rowe's Blog, page 4

April 15, 2017

The Spacehopper

by

T.A. Barfield

thumbnail artwork by Rene Castro

Editor’s Note: This fine story is the winner of our 2017 Southern Pacific Review Short Story Contest.

The Spacehopper

She’d always been a very literal girl.

The street is clear, the neighbours having received advanced notice from her father’s polite, Banda-machined letters. The pavements are empty, but the half-lidded upstairs windows are watching, cheerful for the distraction.

She waits at the top of the hill. Her breathing is steady and her mind is focused. She is judging the light of the stars, replotting her flightpath. The moon hangs low before her. Her father, to her left, reminds her that the moon will exert a force of 0.16g, with the result that she will weigh only 16.6% of what she does in Sheffield. She’s light anyway, for a six year old. Her mother, to her right, has styled her hair for zero-gravity.

There are the final checks. The guidance system is put through its paces, the little glass wings from the defunct MG folding and unfolding on command. There is a concern over a persistent minor yawing to the left, which might require a course correction. She can use the Cutler’s Hall as a waymarker, in case of windshear. The hot-water bottles are at full operational capacity, the water warming her little body gently against the cold chill of the interested evening. The city lies beneath them from this hill, splendid and dark and expectant with secrets.

Her mother adjusts her provisions in the red plastic lunchbox: a small cold supper and a tight roll of foreign banknotes, most now removed from circulation, curled up and sealed in a jiffy bag. No-one knows where she might return. Her father nurses his continual worry that she might not maintain aerostatic equilibrium.

Pressure is building. Without announcement, the street knows that the moment is come. Releasing their grips from her shoulders, the parents retract, locking their arms together at a safe distance. She seizes the rubber horns firmly, a solar voyager taking in those final breaths of her familiar world. She is alone.

The ascent begins.

He had a genius for finding those old-fashioned toys, out-dated and gauche from when even they were young: catapults frail with decaying elastic, Styrofoam planes to buzz like dying insects, small wooden boats which turned-turtle as soon as they scented water. And now this.

The smell of the rubber unnerved her, thick and flaking like a set pudding from a foil packet. It was an old smell, one that belonged with the chemical wash of lino at school, or her grandmother’s window-spray. It was its age that was frightening, like that smell of the rubber sheet she’d been placed on at the hospital. There’d been no plastic gossamer fabrics nor the clean, white synthetic fibres that you saw on the TV. There was just the rubber mat. She was their only child.

She’d taken against it as soon as he’d shown her, blinking and pleased. There was something obscene to the gift, both in the smell and its flaccid rotundity. It wore a face: two eyes and a gaping, foolish mouth, all misshapen from the lack of pressure – the look that you get when a person had been laid out: their features stay the same, but their face has somehow slipped away. Anyway, how on earth was she supposed to wrap something with that awkward shape?

She always thought it was some reflection on their having had her when they were, comparatively, elderly. It was as if they had skipped a decade somewhere, bringing up a child out of time and out of tune, playing with toys from a generation before, sharing fascinations that had faded on most bedroom walls, even dressing like the past. You bring up a child as you know how, she’d always thought. There’s no choice to when or why.

They hadn’t intended to have the child. But two bottles of Mateus Rosé won at a CAFOD anti-famine raffle at church had decided otherwise.

But she was free of at least part of it, their heavy age. Although she was wiser, more thoughtful than by right a child should be, she still had that desire to run, to break free, to explore. Youth had broken through the grey years of their poverty after all. Her mother couldn’t understand it. She had no desire to escape, no desire even to return to rooms in her own home that she’d seen but had no use for: the attic, the cellar, her husband’s shed in the backyard. She’d been clever as a schoolgirl, but somehow it hadn’t stuck. Her high marks and high green stockings had all been folded away when she was eighteen, never to be taken out again. Somewhere, something inside her had failed.

She must get it from him, this desire for exploration. And certainly, he responded, urged her on, supported and encouraged her. A blurred figure seen through plastic glass, he moved amongst the baize boards of his shed, diagrams and sketches coruscating across the square-lined paper he’d tacked to every wall. If his daughter wanted to voyage between the stars, he would make it so, hammering and borrowing and gluing and soldering a universe of iron stars for her. The six-year-old girl, holding her space vehicle still uninflated, would sit on his bench and plan with him.

She was so keen, she had to help.

And so, in preparation for spaceflight, her mother began to raise a series of key practical concerns that required consideration before launch.

What if she did not achieve escape velocity and returned to earth on one of the city’s six other hills? Could an appropriate landing protocol be agreed?

It would, her father averred, be preferable to launch from a more equatorial location, due to the nearer proximity to space. The Derbyshire Dales, suggested her mother, but then withdrew the idea, anxious that the child would not know the landmarks for navigation. She might also catch cold.

What about the cold? Three new hot bottles were purchased from Aldi at a reduced price. Their own hot water bottles were out of the question, according to her father, due to the increased febrility of the material following that cold snap in February. Any leak could prove catastrophic: just look at Challenger. Her mother reconciled herself to the expense with the thought that the water could function as emergency supplies, should aphelion take longer than expected.

Finally, there was the question of tracking, once the journey had begun. The roof of the backyard shed wouldn’t support a radar dome. Besides which, the child’s father was in the process of installing a roller-shutter skylight to accommodate the new telescope.

For once, it was her mother who found the answer: a swathe of brilliant sequined material from the defunct dance studio the road over, swapped for a black forest gateau she’d bought once and forgotten about in the freezer. This was quickly Singer-ed up into a dress that sparkled with the brilliance of a whole galaxy. The child turned and twisted before the mirror in delight, stars blooming and fading like the swift passage of the aeons. They would be able to track her by her light blazing across the zodiac.

It was two days prior to launch. The question of inflation became urgent. A bicycle pump, used up till now for the helpful engorgement of the neighbours’ footballs since they did not own a bike and, in any case, had no desire to go anywhere for pleasure, was deemed too weak for the task. From the man two doors up, he borrowed one of those emergency car tyre inflators. The man had no car in any case and was only keeping it against future use. Now it rattled away, plugged into the Vauxhall, walking up and down the cobbles and chattering to itself like an angry crab in a box.

And as it chattered, the globe swelled. She stood beside it, watching it bloom, testing its surface turgidity with a solemn hand. All would be well. Her father watched her composure with pride and a mounting sense of excitement. Her mother stood in the window, counting.

But wait. There was a last minute theoretical concern: magnetic interference. The crisis reigned for several hours and the child began to consider the possibility that her voyage would not begin that week. But her father was undefeated and set about the reconstruction of the guidance system; gone were the steel hinges from the old Mini Metro’s bonnet, replaced instead with the plastic hydraulic mechanism from the former greenhouse windows. Her mother undertook to remove the brass buckles from her duffelbag and to ensure the absence of kirby-grips in her hair. The clock was ticking again.

With 24 hours to go, they held a small party in the kitchen. A celebratory lunch on the day itself had been ruled out in case it interfered with the delicate weight, mass and moment calculations necessary for take-off. Her mother, when she discovered the lost black forest gateau, had also found a microwavable set of Chinese appetisers, hiding under the ice. Under the kitchen light, they nibbled on defrosted vegetarian spring rolls and tiny slithers of Peking duck, already planning the next itinerary to Alpha Centauri. It was only the three of them. Her mother hadn’t been sure whether there was anyone else to invite.

Following the special Chinese meal, she helped her daughter get ready for bed and then, unusually for her, sat and read a bedtime story. She hadn’t done this for many months, the child, holding a generally literal attitude to life, preferring lists of useful facts and entries read out to her from the Children’s Everyday Encyclopaedia. At the end, hovering by the door, her mother could not bear to turn out the light.

The day dawned, splendid and awful. The street held its breath.

Bending her knees, she tests the response. The great vehicle shifts under her weight, pushing back, full of terrible, wonderful repressed power. It will serve her well. She tightens her hands again on the rubber horns. She is ready.

With her first bounce, she is only as high as the downstairs windowsill. With the second, she waves to the neighbours. With the third, she soars over the chimney pots. With the fourth, she leaves the street behind.

On she sails, beaming, triumphant. The interstellar voyager, venturing across distances unknown. The moon calls to her, its warm light beckoning, its cratered face smiling gently.

Her mother, screaming for her lost child, runs after her in the streets far below.

Author Bio

T.A. Barfield was a student at the English school which claims the most number of ex pupils eaten by tigers. At present, he has no desire to add to this achievement. Having studied English at Durham, Oxford and Cambridge, he taught for a number of years at several schools, teaching Shakespeare, Waugh, existentialism and magical realism. He has recently written a novel and is currently searching for a publisher. He divides his time between Britain, Belgium and France.

April 6, 2017

Hydration: Three Poems by Jan Wiezorek

by

Jan Wiezorek

thumbnail artwork by Rene Casto

O!

If you sit and wait,

your limbs weigh heavy,

pulled down, the skin flakes

base your coffee mug.

I noticed this this morning.

My left arm shook dark,

hot mess on my robe.

I will not choose ice water.

Skull flakes round my cup,

where on that dark table

lives a circle, my blessed o!

Newbie Spring

Roof held by sagging

vital breezes and clothespins,

backyard shed of forgetful rituals,

flowering baby-food lids

cupping hands, held tight

since last season.

Wander down suckling path

toward lake that diapers ice

cut thin by warm blankets.

I stand and wait to hear

dashing burbles of laughing gas

let loose under icy bundles.

Listen for small fry

who hiccups

new life to spring.

Harbor Mind

I’ve trained myself to wait

on whispers, but the dishwasher

drums daytime heartthrobs.

Heating elements tick

diablo rhythm and castanets,

cracking ceramic ridges

behind my eyes. Walking by,

my outside mind gains

harbor calm and floating pen.

I place myself near pliable skiffs

waddling geese wheels; names

so familiar to me that I can spell

them: Mermaid with her tail

resting on sawed wood dock,

and Thundermug for music

strained through Guatemalan

brew. Water always

gets me, its rabbi balancing

on board, pushing her out

from shore, and raising love coos

Author Bio

Jan Wiezorek has taught writing at St. Augustine College, Chicago, and his poetry has appeared or is forthcoming at The London Magazine, Panoplyzine, Better Than Starbucks, and Schuylkill Valley Journal online. He is author of Awesome Art Projects That Spark Super Writing (Scholastic, 2011) and holds a master’s degree in English Composition/Writing from Northeastern Illinois University.

March 21, 2017

Buenos Aires Protest: No Police in Sight

by

Jonathan R. Rose

photo by Beatrice Murch

I once participated in a protest in Mexico City, days after the current president, Enrique Pena Nieto, was elected. And what I remember most was the amount of police officers present. I tried to count them, but there were far too many.

Each police officer was draped in riot gear. They were all holding shields and batons. It was an unsettling, scary feeling seeing that many cops, standing side by side, encasing the thousands of protesters, waiting for something to happen just so they could react. But the fear faded when I started to realize there was something encouraging at the sight of so many cops, something empowering, something validating. Whether or not the government was afraid or even worried about the protest is anybody’s guess, but they were aware of it, and judging by the extreme measures taken in response to it, they were taking it seriously.

This brings me to a protest I observed in Buenos Aires, on March 7th of this year.

Walking down one of the city’s main streets, Avenida de Mayo proved difficult. There was no room to move. The street was completely filled with people. Many of them were wearing shirts indicating their support for one of the many workers unions present. They were waving enormous flags, banging on drums, blowing horns, chanting, shouting, fist-pumping, eating, drinking and chatting. I watched people shouting speeches through a microphone at the head of the protest. I heard rousing words about fighting back, about standing up, about banding together, about not taking it anymore. The speeches were met with thunderous rounds of applause and shouts of approval by the crowd. It looked like any other protest I’ve seen, except for one thing, there was not a single police officer present, at least not one in uniform.

I couldn’t get over the complete absence of law enforcement. Was there a peaceful accord made between the protesters and the authorities prior to the protest? If so, does that not defeat the purpose of protesting? Is it even a protest when you ask permission to do it by the very people you’re protesting against?

I have no idea what took place prior to the protest, behind closed doors. All I know is what I saw, and what I saw were thousands of people blocking a major street in the middle of the afternoon, on a weekday, and not a single cop there to see it.

While I felt afraid of during the protest in Mexico City after seeing so many armed cops present, it was that fear, that tension, that possibility of danger, that made it seem like it mattered being there. But feeling no fear during the protest in Buenos Aires, feeling comfortable, feeling at ease made it seem like my presence on that street didn’t matter at all.

Is it possible for comfort and safety and protesting to co-exist? Or is the price one pays for protesting supposed to be the prospect of getting hurt? Is that not the sacrifice one is supposed to make before leaving their home and protesting on a major street against a figure or system of authority they deem unjust? I was always led to believe that protesting was supposed to come with some risk, but on that day in Buenos Aires, where was the risk if not a single cop was there to impose it?

After the protest ended, I returned home and sat in front of my desk, thinking back at what I saw, but more so at what I didn’t see. I questioned if having no police present was a possible strategy carried out by those being protested against. As I mentioned earlier, seeing all of those cops in Mexico City, while frightening, was empowering. It made me want to be there. It made me want to stand up against the newly elected government. So what does it mean when not a single cop shows up in Buenos Aires during a massive protest that blocked off a major street for several hours?

I also thought about the history of what the people here in Argentina have done when faced with an unpopular government. Unlike many other countries, when faced with governments they deemed unjust, Argentineans fought hard to oust them. It wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t without heavy losses and a great deal of bloodshed, but they did it. Perhaps that history of successful opposition is what led to the absence of police during the protest I witnessed. Perhaps it was a sign of respect for the people on behalf of the government. Perhaps it was even fear, though no government in their right mind would ever publically say they were actually afraid of the people they’re tasked to govern.

Or maybe the lack of police presence was a sign of disrespect, the government’s way of saying they were not afraid of the people at all, like a boxer so supremely confident in his opponent’s inability to hit them they don’t even bother raising their fists in defence.

I also considered the possibility that police were there that day, but I just couldn’t see them because they were in plain clothes, hidden in plain sight, mingling, maybe even marching with the protestors themselves, all the while prepared to respond if things reached a level they deemed unacceptable.

When speaking to several people here in Buenos Aires, it was made clear to me that many of them are not happy with the current government. And while I don’t have the answers to any of the questions I’ve posed, I have no doubt that answers will nonetheless be forthcoming in the not too distant future.

March 2, 2017

Howling Wind, Cosmic Telegraph, and The Elusive Aurora

three poems by by Jorge Sánchez

thumbnail artwork by Rene Castro

Howling Wind

When the wind moves its rapier sharp voice

against the finials of the building’s spires, who

can stand the screeching questions? At dawn,

the men sit on the shore awaiting light,

perhaps a ship whose inner form is light,

a ferry borne from the foam of a dead sky.

A seven-part song has caromed the walls

like a new moon, its dark light adrift

on the dreams of young men and boys.

What good idea do you have now, John?

The compass you lost, has it floated up? Has the sand

taken it, like a souvenir, or a letter home?

Cosmic Telegraph

When going down Devon for most of time

and when the license plate of the Chevy in front

spells out the most unlikely message, who

would believe it? And who would be the source?

The blue of the sky was a graceful, swooping thing,

a space full of the quiver of arrows. One.

To leave is not to come back, except by cosmic

telegraph. The scrawled note on ancient

chalkboard. The whisp of smoke pre-dawn,

and the beach where we, all wet, would greet the sun.

The Elusive Aurora

When even the Geophysical Institute

thinks there’s a chance, I glance northward

like the cement figures of the facade

and consider the possibilities of direction,

the exigencies of fog, but for what?

The window pane is but mirror, a dance

in glass eternal to the sky. Forward. Back.

The eyes in my head are the only ones

I have. My clothes are coated in dust.

The cats cannot learn our language yet.

Author Bio

Cuban American teacher and poet Jorge Sánchez was born in Hialeah, Florida, and raised in Miami. He earned a BA from Loyola University, an MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan, and an MA from the University of Chicago Divinity School. Sánchez teaches at Elgin Academy in Elgin, Illinois, and lives in Chicago with his wife and son.

Teaching English at the Cigarette Factory

by

Cathy Adams

Thumbnail Photo by Matt

Everyone in Han village smells like tobacco from their fingers to their hair to their clothes to the pillows they lay their heads on at night before getting up the next morning to return to work at the cigarette factory. Nui Die Cigarette Factory stands twelve stories tall in Henan Province, China. Macy Gray teaches the workers English, and it’s the first job she’s ever had where the people she worked with didn’t confuse her with the singer and make jokes about her name. The only Macy Gray anyone in the village had ever heard of is the brown-skinned, thirty-five year old vegetarian English teacher, born in a land called Tennessee in America which must be somewhere near California because that is the only American place many of the tobacco workers know by name. On the day that Macy Gray brought a Macy Gray CD so that her students could learn the English lyrics they all saw the name and the tall dark woman on the cover, and they were sure that their teacher must be famous in America since she had her own music CD. Even when Macy Gray the English teacher tried to tell them that she was not the Macy Gray on the CD, they would not believe her, so she became Macy Gray the Singing English Teacher.

At the end of each class Macy played a song on a stereo system she had found in the top of a closet. The sound was tinny and not nearly loud enough for all the students to hear well, but this was the part of class the students looked most forward to most, and a kind of spark went round the room when they saw Macy pull out a CD case after their recitations. While they listened, she wrote the lyrics on the board and then played the song again so they could sing along. They often forgot the grammar they studied from the blackboard, but they never forgot song lyrics.

The room where they took their English lessons on Tuesday and Thursday nights was cold with cement block walls that had at various times been painted blue, then gray, then white, and chips from all the colors showed up in dirty tags along the wall about three feet from the floor as if a flood had filled the room at some point and washed away layers of paint in random places. But this room was on the third floor, so no flood except a broken water pipe could have peeled away the ugliness to reveal even more ugliness. Above the tags of peeling paint was a disturbing mural painted by either a child or a badly trained adult. The series of didactic images had perplexed Macy Gray, the Singing English Teacher, since the day she began teaching basic English four months earlier. A flower eating a dirty child must mean that if you do not wash properly you will be eaten up by beautiful things. A man in a wife beater spitting on the ground was being smashed in the back of the head by an angry woman, so if you spit and do not wear proper clothing, you will be given a concussion. A person sitting in a recliner, presumably, a dentist’s chair, with spurts of red paint on either side of his mouth and a man in a red spattered apron reaching into the reclining man’s open mouth must mean that people who fail to take care of their teeth will have them forcibly and painfully removed by a person who may be a dentist or possibly a butcher. The pictures were distracting to the point that Macy had repeatedly asked that they be painted over. The Major Assistant Shift Supervisor, Jaoji, who proudly wore a badge that read Major ASS, and with who served as Macy’s singular contact with the company, always smiled and said things to her in Chinese about the importance of their lessons and so the pictures were unaltered and forever staring back at Macy Gray day after day. Her students paid them no mind. They sat down in the breaking and broken folding chairs, smoked cigarettes one after another and repeated everything Macy said or wrote on the chalk board that Major ASS Jaojie had requisitioned for their classroom.

There were no books, and when Macy asked Major ASS Jaojie for copies of study sheets to be made for the students, he said it would have to be approved by the Senior Assistant Shift Supervisor, Mr. Chen, and that he would have an answer for her by the next week, maybe Tuesday but not later than Thursday or Friday. So Macy Gray waited for the Senior ASS to tell the Major ASS if they could make fourteen pages of study sheets for their students.

Macy began the laborious job of writing the recitation lines on the board and pronouncing the words for her students to repeat. Her students removed the cigarettes from their mouths before they loudly parroted the lines, keeping their eyes on the green chalk board. A few dutifully took notes, quickly wiped away the ashes that fell on their papers, and practiced their lessons outside of class with a dedication that Macy Gray had never before dreamed possible when she worked as a second grade teacher’s assistant at Davis Hills Elementary School in Crossville, Tennessee.

Are you going to the dentist today?

Yes, I am going to the dentist today.

“May-si! May-si!” said Xu, bustling into the classroom, out of breath from walking up the three flights. He lit a cigarette as soon as he got to his seat and breathed it in with gusto. He had been working at Nui Die since he was fifteen and smoking since he was twelve, or so he liked to say. “I am late,” said Xu.

“He is too late for love,” said Marilyn Monroe, the oldest member of the class.

“It’s late in the evening,” Crazy Star called out.

“It’s late, it’s late,” said a few others.

“Good, those are good,” said Macy.

“I am sorry,” said Xu, lighting a second cigarette off his first one, but he was smiling, and the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes belied any regret.

“I think that sorry seems to be the hardest word,” shouted Crazy Star again.

Several students began writing furiously in their thin paper notebooks, their lips moving as their pens scribbled.

Smiley waved her hand in the air. “Is it time for Word Share? I have words to share that I learn from my brother cell phone music.”

“Sure, Smiley. We can do a Word Share. Come up and do it the way we practiced.” Macy waved her hands dramatically toward the space in front of her desk, and Smiley, clutching a folded piece of paper, pushed up from her seat and made her way to the front.

“Everyone, give Smiley your attention for Word Share.”

Smiley unfolded the paper, and mouthed the words to herself for a few seconds.

“Go ahead,” said Macy, nodding warmly.

Smiley nodded back at Macy and mouthed a few more words before she began. “My man pay me e’ry week. All dese bitches having babies all de weeks. I always be the beydest nigga, I go shrating in the shree.” Smiley lowered her paper and smiled broadly at Macy whose face had turned gray.

“You can take your seat now,” she said, her voice a strained whisper. It took a moment for Macy to even notice that her hand was waving in front of her face in useless little motions. But the class didn’t hear anything she said because they were busy clapping for Smiley who had happily returned to her seat.

“Okay, okay. That was.” Macy wiped her fingers over her eyes and took a deep breath before resuming the class. After forty-five minutes of discussion about a trip to the dentist’s office, Macy took the stereo down from the closet.

“Tonight we’re going to learn some new words about love since it’s almost a special holiday,” said Macy.

“Can’t nothing bring me down. I am so too high,” said Xu, still smiling.

“Good, Xu. But soon it will be a special holiday. Does anyone know the special day that’s coming?”

The room was still and silent. “Valentine’s Day is in two days, and that’s a special day of love. In America we celebrate it by giving flowers or candy to the one we love, so for tonight’s lesson we’re going to learn new words from love songs.”

Marilyn Monroe sat erect in her seat. “I know love songs from Taylor Swiff.”

“Yes, but we’ve already had Word Share tonight.” Macy took a folder from her backpack and took out a small stack of papers.

“And too proud to beg!” shouted Xu. “Sweet babeee!”

A hand went up from the back of the room. She was the newest member of the group, a village woman in her late twenties who stared intently at Macy each class and took many notes.

“Yes,” said Macy, giving the young woman a big smile, “your name is Cloudy, right?”

Cloudy held her hand up just above her face. Her skin was darkened from years of working outside in the fields, and at her young age she already had lines around her eyes. She spoke with a voice barely loud enough for Macy to hear. “Why that woman was crying?”

“What woman was that?”

“The woman in the song you play other class. She was the most beautiful woman in the world. So why would she cry?”

“Oh,” said Macy, searching her memory for the lyrics. “The singer was asking if she was crying.”

“The beautiful woman was not crying?”

“I don’t think so, no. He was asking, um, if anyone had seen her,” said Macy, clutching the folder in both hands.

“She was the most beautiful woman in the world, so she should not cry. A woman who is very beautiful should not cry,” said Cloudy, in a voice a little louder.

“Well, Cloudy, even beautiful women cry sometimes.”

“She have no reason to cry. She is the most beautiful woman in the world,” said Cloudy, her voice more adamant this time.

Macy grabbed the stub of chalk that she kept in a small pocket of her backpack and wrote out the chorus on the board. She brushed her fingers off and turned back to the class. “Okay, now let’s repeat.”

She wrote the lyrics to “I Can’t Stop Loving You” you on the board as Ray Charles churned out the words on the tiny stereo with an echoing brassy chorus following him. After about a minute, feet began a slow tap.

At nine o’clock, after playing the song three times, enough for most to sing along with the chorus, Macy bid them a good night and began gathering her notes. Each student gave her a separate and formal, “Good-bye teacher!” before passing by the dirty child picture on the wall as they departed. She responded in kind to each until only Cloudy remained. Up close Macy could see that her face was young, but the darkened skin from the sun made her look aged in an odd way, like a young woman who had been made up to play the part of a grandmother. Macy realized she probably would have been finishing her final year in college, if she’d been born elsewhere.

“Did you have a question?” Macy asked, making herself smile patiently.

“I am not understand,” said Cloudy. “This happy woman not cry. This words make no sense.”

“Oh,” said Macy, “you’re still talking about that song.”

“Beautiful woman cry,” said Cloudy, growing angry at the words.

“I’m sorry if the song confused you. We’ll learn some new ones next class,” said Macy. She wanted to get out the door and outside where she could breathe air not polluted by twenty cigarettes. Cloudy stood unwavering.

“I am not cry,” said Cloudy, but her face was growing red.

“Of course not,” said Macy. She glimpsed the door for someone else, anyone, but they had all made their way down the three flights to the outer doors.

“I am not cry when they take down this building or the village. I am not beautiful, but I am not cry.”

“What are you talking about?”

“This place, all place, take down one week. Everyone move to new apartment.” Cloudy pointed a finger toward the window at the half completed high-rise across the street and down about a block. “All have new home. Beautiful women should not cry.” Cloudy raised her trembling chin and headed out the door. Macy looked back at the building out the window.

Back home in her apartment that night a call to Major ASS Jiajie hardly clarified the situation.

“Yes, they take the Nui Die building and Han village down.”

“What?” cried Macy. “They’re going to demolish the building where we have our classes? And the village, too?”

“Yes, demolition.”

“But why the village?”

“Build another building,” said Jiajie. “They will build tall beautiful home for village, too. Old people are happy about this, they will not have to live in old house. New home for everyone. Is very good for everyone. Is okay. We find a place for your classes.”

“When were you going to tell me they were taking down the building?”

“Maybe Tuesday,” said Major ASS Jiajie.

Macy did something she had never done to anyone since arriving in Henan. She hit the “end” button on the call without a proper good-bye.

She sat by her window looking down on the light flooded street below and the never-ending string of cars that passed by her apartment building. The apartments that Cloudy had pointed out earlier were decorated with red and yellow lights around the entrance and signs with characters covered the front windows. The factory workers walked home after class past the lights of the town and into the night to their village which lay about one kilometer east. From the high window of their classroom she watched them disappear, but she never saw where they went. Macy had never seen Cloudy walk in or out with anyone since she’d joined the class a month before. She always seemed to be on her own, a highly unusual phenomenon in a country in which people were simply not allowed to go anywhere alone. Someone always tagged along.

The class dragged on with a dialogue between Sarah and Tom on a date: they ate pizza, they held hands, they went to a movie, they scheduled a second date. After their recitations, Macy played “Rainy Days and Mondays” by the Carpenters. The class smoked, tapped their feet softer, and then left amidst their usual banter. Cloudy walked without speaking to anyone, and Macy stood at the window watching the top of Cloudy’s head as she moved, a dark dot on the sidewalk.

It wasn’t easy to fall back in the crowd and not be noticed, especially for a laiwei like Macy. She hid her hair underneath a tan scarf, which made her only minimally less noticeable, but her skin she could not hide, and at 5’11” she was taller than most of the men she passed. She fell further and further back hoping Cloudy would not turn around. By the time Cloudy reached the entrance to Han village Macy was so far behind, the young woman was a dark speck in the distance. But unlike the others from the class, Cloudy didn’t turn onto the dirt path to the village, and for a second Macy wasn’t sure she had followed the right person. The tiny figure continued walking down the shoulder of the road past the village, so Macy increased her stride to shorten the distance. Cloudy went almost half a kilometer farther before she stepped off the road to her right and into a thin copse of evergreens. Macy hurried to keep sight of her.

The ground was damp and Macy’s heels sunk into the dirt. Cloudy’s figure was almost invisible as she moved down the darkened path toward a short row of cement block houses. A dog began barking and someone shouted at it in shrill tones. Walking the full length of the short row, Cloudy went into the last house and Macy stopped. She looked around for a tree to hide behind, but there were none thicker than her arm. Fields full of lines of something in its dying phase surrounded the dingy cement houses and the spindly grove of trees. Browned stalks disappeared in the darkness as far as Macy could see. There was not another house or building anywhere except for the houses where Cloudy had gone. Macy had never seen anything so remote up close in China. Every other place she had visited was pressed close with buildings, people, animals, and cars. This place was like the edge of the world.

“You should wear more clothes.” Cloudy’s voice startled Macy. She had somehow come out of the first house on the row and now stood almost behind Macy.

“How did you get over there?” Macy pointed back at the door she had seen Cloudy go into.

“I live here,” said Cloudy, holding out her hand toward the tiny row of houses. The cement blocks were darkened across the bottom with dirt and peeling paint. A row of chairs sat in a jagged circle around a low table, and a few meters to the right was a blackened pit in the ground where someone had cooked a meal a short time earlier. From the looks of the scattered plastic and food scraps, someone had cooked many meals over that pit. Cloudy watched Macy as she took in the sight.

“Chi fan le ma?” asked Cloudy.

“I’m not hungry. Thank you,” said Macy. She pulled at her shoulder bag and opened her mouth but suddenly felt the depth of her insensitivity. She was another ignorant foreigner with no real idea of her purpose. She had come to teach the employees of the cigarette company English and had planned to start a children’s class as well. She was going to begin with the names of animals, and she’d already begun making flash cards from pictures she’d printed from the Internet. The idea had been such a good one when she arrived months earlier, but now in the darkness at the edge of the field and the sad white houses, Macy began to cry. She turned her face from Cloudy who watched her wordlessly in the dim light. In a moment a very old woman exited the house in the middle and began speaking to Cloudy who conversed with her a moment before turning her attention back to Macy. The old woman remained near the door, staring at the tall crying black woman dressed in fancy shoes and clothes that were too thin for the weather.

“You need more clothes. It is not good for your healthy,” said Cloudy.

“Yes, you’re right.” Macy wiped her face with her hand and then added, “I wanted to make sure you got home okay. I thought you lived in the village with the others.”

“I live with Nai Nai.” Cloudy gestured toward her grandmother lingering in the doorway, picking at her few remaining teeth with something small and sharp.

“I’m sorry about the factory,” said Macy. “Will you lose your job?”

“I don’t work at the factory.”

“But you come to the classes.”

“Yes. You will not tell?” Cloudy’s face took on a look of worry for the first time.

Macy stepped a little closer. “No, of course not. I was just concerned when you told me about the buildings. I thought that maybe you might lose your home, or. . .” She wasn’t sure what she thought and her hand flew out in a useless gesture.

“These house no village,” said Cloudy.

“I see. So you work the fields?” asked Macy, looking out at the darkened stalks. “What do you grow here?”

Cloudy held a hand toward the fields and seemed to be searching for a word. “I don’t know the English.” Cloudy laughed and hid her mouth behind her hand.

Macy looked past Cloudy at the flat roofed square house. Someone had propped a mismatched array of plastic pieces next to an outer wall, like broken construction supplies. Hardly any grass grew around the house surrounded by dusty patches of dirt pocked with stones. “Will you and your grandmother be alright?”

Cloudy smiled in confusion. “Of course. Do you want to stay?”

Macy shook her head. “I’m sorry. I made a mistake.” She turned to leave and felt the tears come hard and fast.

“Teacher,” called Cloudy. “I hope you will not lose your job. We can feed you if you need eat.”

Macy looked back at the tiny figure barely visible now in the dark. “We have nice home and many delicious food.” She waved proudly back at the row of houses.

“Yes,” said Macy, hoping Cloudy could not see her face through the darkness. “You really do.” She made herself smile to save face. “Cloudy, why do you want to learn English?”

Cloudy’s mouth began to turn down a little, as if she had been caught doing something bad. She looked over her shoulder at something. Macy could see that her grandmother was still standing in the darkened doorway. “Nai Nai say I find a husband in the classes.”

“Oh.” Macy thought a second and then said good-bye and began walking back up the dirt road.

“I like to hear the songs,” Cloudy called out. Macy was almost to the treeline when she heard Cloudy shout, “Macy Gray.” She was running toward her. Cloudy looked over her shoulder and stopped. Her voice dropped to a whisper, “I am not cry.”

Author Bio

Cathy Adams’ first novel, This Is What It Smells Like, was published by New Libri Press, Washington. Her short stories have been published in Utne, AE: The Canadian Science Fiction Review, Tincture Journal, Upstreet, Portland Review, and thirty-two other publications. She earned her M.F.A. from Rainier Writing Workshop at Pacific Lutheran University in Washington. She lives and writes in Liaoning, China, with her husband, photographer, JJ Jackson.

February 21, 2017

Prostitutes, Masseuses, Call Girls in Viña del Mar and Santiago, Chile

Here is a guide for the foreigner of the sex trade in Chile.

Legality

In Chile prostitution is legal. A woman is allowed to operate as a call girl and negotiate business in her own quarters or her customer’s. A brothel is technically not allowed, but there is no enforcement of that and it is easily hidden behind the facade of a massage parlor anyway.

Types of Services and Prices

There is a regular massage, erotic massage, and sex. The women here are beautiful and there is no stigma attached to this so they are just regular, attractive girls and not, say, the criminal element. Chileans, unlike Americans, see nothing dirty in this business. You can kiss on the lips while the woman will keep her modesty by disguising her face on the web site where you found her.

Most prostitutes are Chilean but there are Argentine and Colombian girls working here too. Some come to Viña from Argentina for the summer tourist season (Jan-Feb).

If you want a massage with an erotic finish then ask for that. You will get annoyed when the woman cannot give a muscular firm massage and only wants to give you sex. So it is better if the woman has massage certification (certificado de masaje). In Chilean, education certification is looked on favorably in any kind of employment. It is better to hire someone with that to get what you want.

The erotic massage will be 30,000 CLP. Add 10,000 CLP more if you want the woman to be nude when she gives you a massage and when she finishes you off (One website says “tener feliz fin” meaning “with a happy ending.”) Otherwise she will finish you off with her clothes on.

You could also add 15,000 CLP to what you pay the masseuse for intercourse. Or you could just start with a hooker in the first place. They cost 50,000 and up.

If you want them to walk a parade of girls in front of you and then pick one, try this massage business Masajistas Sensitivas.

Safety

There is no mafia or anything like that overseeing this business. There is no danger and you should never feel unsafe. It’s as gentle and soothing as selling flowers.

In Santiago, go to Providencia as most of the women operate out of apartments there and it is one of the safest, upscale neighborhoods. In Viña del Mar you will want to stay around the Libertad and other streets near the city center and beach.

Where to find Hookers and Erotic Masseuses

Use the Locanto website, which is just classified ads. If you are looking for a rub and tug massage then that is “masaje erotic” in Spanish. Click this link for erotics massages in Viña del Mar. Click here for hookers in Santiago. Send them a text message or WhatsApp. You could write: “estas disponible?” meaning “are you free?” Then use Google translate to get her address (que es su direccion?). For their own safety, they will not want to put their address in an email or text message. So they might tell you a general address and then you call back for the specific one when you get there.

Try Chilean Culture: Cafe con Piernas

If you are in downtown old city-center Santiago go to a Cafe Con Piernas, which is a stand up semi-erotic coffee shop. You get coffee or hot chocolate and get to entertain young women dressed in sexy lingerie and be entertained by them. There is nothing dirty going on here either: no sex, no touching, just a friendly chat. Men come here from their offices in ties during office hours. Find the cafes in the galerias, which are the vast shopping spaces inside the large builders around the city center. They should have some neon lights perhaps to help you spot them.

Love and Sex with Chilean Women

Finally, for traditional dating here is some dating advice and description of the general love landscape for the lustful wandering male.

February 5, 2017

The Disappeared

Three Poems by Mark Trechock

by

Mark Trechock

photo by Rodrigo Paredes

Dancing on a Rooftop in Buenos Aires

The other guests came in ones and pairs

from desperate jobs vending gewgaws

or taking orders at pizza restaurants,

shook hands formally with the host,

who spent a good hour testing the heat

and strength of the yerba mate before

its passing, solemn as a bishop’s high mass,

between sips the communicants asking

blessings and health for kindred and compadres,

curses for Menem, for Bush, for the dirty

war, the inflation, the intermittent

electricity and water, for the “misery villages,”

for the robbery of Ernesto’s few worthless bills

and his clothes and shoes and his long walk

naked home, and the lack of working telephones.

Midnight, the evening just starting, we climbed

the stairs to the rooftop where cuts of beef

were roasting over a spit, the red wine

uncorked, the broom dance just beginning,

one misstep close to the edge and twelve

floors straight down to the concrete already

breaking up from half-repaired

sewers and other public works.

At the two a.m. supper, one compadre,

a Methodist student of divinity,

sat on the roof with a gaucho knife,

fit to skewer a chunk of beef,

slice a pear, or split a slab of bread.

It took me back to church suppers

at home—the rows of gelatin salads

with cottage cheese, hamburger hot

dish with canned tomatoes, flanked

by sweet bars in aluminum pans

with cooks’ surnames in green magic

marker on masking tape, but nothing

requiring knives, which were never set out,

and certainly no talk of politics, as if

we didn’t know who canceled our votes.

The Disappeared

Appearing only slightly dispirited

that the secret police in their green Falcons

never took him to join the disappearance

of everybody worth killing for the sake of order

six or eight years ago

at some torture house in the Pampas,

or out the cargo door of a chopper,

the theologian sat with me drinking tea

at a time of day marking no specific task or urgency,

as safe and blameless for now as Methodist women

making quilts and gossiping in a church kitchen.

I listened to him wonder if another Fascism

would replace the new yet suddenly abandoned form,

and if the currency would find its level

or keep swirling like the thousand peso notes

blowing untouched down the aisles of Buenos Aires buses,

and when if ever the mothers of the disappeared

would cease parading swaddled photos

of the children and lovers they would never see again

before the successors of their executioners,

sequestered in their Pink House.

I couldn’t say, but thought of how,

at a vineyard in Mendoza the week before,

I toured the vats, guided by a woman

wearing lipstick as red as Reagan’s second election

and the swagger of a suburban realtor.

I sampled a malbec, aged for years

in cellars as dark as the torture houses.

At the last stop, a case of the red

slid down the conveyor and fell to the concrete.

Wine pooled like blood on the floor

as the shipping department stifled

the kind of nervous laughter I used to hear

from children watching horror movies.

It will leave a stain.

Spring 1990, Santiago de Chile

The pavement pitches right to left

to right like a carnival slide,

down from the ice of Aconcagua,

the bus picking up speed

around the twenty-ninth curve,

hurtling past the hillside apple orchards

hung with blossoms,

toward the shimmering smog

arising in greeting

from the city of the disappeared.

At the depot

the brittle staccato of Spanish

clatters to diesel accompaniment.

A street full of young philosophers

stroll through the November spring,

arguing over what might happen next,

cranking to a crescendo at the last word,

unhurried and genial in their force,

only to be countered by another’s burst,

probing the edges of free speech.

“Bush returns to the scene of the crime,”

warns the newspaper kiosk,

as the traffic cops still in camouflage,

machine guns slung over their shoulders,

occupy the next intersection

to protect the man who did away with Allende

and now wants endorsement

for doing away with Sadaam.

I slant my path the other way—

toward the side streets, past

the sidewalk fruit vendors

and the improbable Chinese restaurants

redolent of sweet and sour pork,

seeking anonymous shelter

where Bush would not have made

a reservation.

author bio

Mark Trechock lives in North Dakota and has spent two sabbaticals in Argentina and Peru and made several shorter journeys in Colombia, Chile, Guatemala and Mexico. After a 20-year hiatus from marketing poetry, he recently began resubmitting for publication: poems related to Latin America have appeared in Radius, Life and Legends, Shark Reef, Verse-Virtual, Raven Chronicles, and Badlands Literary Journal

A Half-Assed Journalist’s Half-Assed Journey to Report on a Half-Assed Protest

by

Jack Moody

photo by Fibonacci Blue

I was three hours late, violently hung over from two bottles of cheap wine the night before, and driving thirty miles over the speed limit through the heart of downtown, en route to the “We Stand With Standing Rock” protest—or whatever name they chose this time. I won’t bore you with the details of where, when or with who this protest took place, as I can safely assume that this particular gathering was in no way, shape or form any different from any other impotent attempt by my esteemed generation to “shake up the establishment” (also at the advice of my lawyer).

Distracted by a song on the radio that I was trying to decide whether I hated or not, I slammed into the left headlight of a silver ’96 Corolla filled with horrified local college girls while blindly merging into the turn lane. There was a moment of silent eye contact as we all registered the situation, and then, tentatively, the blonde with the tits rolled down the driver’s window—to say something? But before a dialogue could begin, I threw off my sunglasses (strategically worn to combat the effects of my pernicious hang over) and screamed through my open window, “You bitch! I have a riot to report on; out of my way!” I then sped off down Main Street, fairly confident that I had escaped before my license plate was made legible.

I skidded into a loading zone down the block from the heart of the demonstration and tripped on the curb, adjusting my sunglasses and situating the hood over my baseball cap: this was my “incognito reporter” costume, the idea being that it would make me able to slide between friendly and enemy ranks alike. Upon second thought, I probably looked more like a booze-addled troublemaker, but this crowd would have been lucky to experience any trouble, anyway.

I made my way into the center of the crowd—made up of about fifty peaceful protesters holding up signs and lit joints—and began the process of blending in with the people. A man dressed from head to toe in traditional Native American garb was yelling about equality and the purity of the Earth, as a decrepit, elderly woman banged rhythmically on an animal-skin drum. People were holding hands in a wide circle, chanting some variation of “We Shall Overcome”.

There were no police in sight and everything seemed to be going smoothly. This was disappointing. Where was the clashing of the common people with their armed controllers? Where was the tear gas and masked, self-proclaimed revolutionaries breaking the glass windows of the banks and local businesses? As I said before, I was three hours late, and certainly by now I assumed some kind of clash would have taken place here.

I stood around for a while, watching the man in Native American garb shout about the power of the people and the progress made in North Dakota thanks to the people like us—well, them. I certainly agree with the cause, but can’t lie and say I’ve done anything for it other than crashing a small demonstration smelling like five-dollar pinot noir, and yelling at my computer screen while watching alternative news. People next to me held up signs reading things like “Water is for the People, not the corporations!” and “You don’t own the Earth!”

At this point, I began getting some inquisitive looks from the poncho-wearers and dread-heads, and so buried my nose into my notebook to appear as though I was truly reporting on the event. This is what I wrote: man not making any sense. blah blah blah. don’t forget to pretend to be interested. Soon after, some protesters near me noticed that I must be a journalist in some capacity, and approached to make their comments. The following is the conversation that took place between myself and a young man in a torn army jacket and red-dyed dreads:

Hippie: You writing for the cause?

Me: …Yes. Yes I am.

Hippie: You need to let the people know.

Me: What should they know?

Hippie: That we’re here, and those fuckers on Capitol Hill can’t control us anymore.

Me: So who’s starting the fight with the cops?

Hippie: No one…this is a peaceful protest.

Me: Do you think you’re accomplishing anything here today?

Hippie: We’re changing the global consciousness. We’re letting our voices be heard, man.

Me: So when does the riot start?

Hippie: Who did you say you write for?

Me: Uhh.

I excused myself and bought a pot cookie off a toothless man in a Grateful Dead t-shirt walking through the crowd with a sign on his back that read “Trump President. World Ending. So Get High. $5”

With that, I decided that I had gotten what I needed out of the gathering, and left the heart of the crowd as a woman in her mid-twenties began chanting a string of guttural noises into a megaphone. Upon returning to my car, no ticket sat on the windshield. I chalked the day up to a success and drove out of downtown, to the nearest bar.

I compiled other quotes and other experiences that day that perhaps were noteworthy enough to include in this piece, but I’ve been drinking and by now, the whole thing is boring me. We live in a time and generation of apathy and the Lemming Syndrome; all that matters is what side you were born into, thus determining what it is you’re going to be apathetic towards and what you’ll be following; it’s all laid out for us. No one crosses the picket fence anymore.

Our beliefs are developed in factories and sold to us through technology that fits in the pocket of our ripped, skinny jeans. Those that believe they are going against the grain, those that believe they are being an individual, were cut out of the same shapes used six decades ago, but are simply wrapped in brighter packaging. Irony will be the death of this generation. Do I think we make a difference? I can’t know just yet. But do we really care? Is that why we act out like we do? Or are we just obsessed with being special—more concerned with being the people that made the difference than in making the difference itself? Fuck if I know. I suppose I just like being the lemming that didn’t jump off the cliff. That doesn’t make me any different though, does it? Ha, the irony is killing me. Whatever.

January 26, 2017

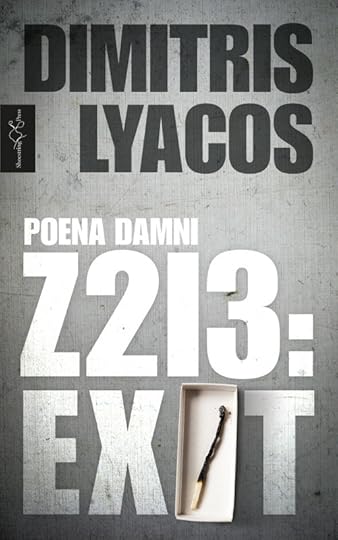

Z213: EXIT

Review by Ilias Bistolas

Series: Poena Damni vol. 1

Paperback: 152 pages

Publisher: Shoestring Press; 2nd Revised edition (October 18, 2016)

ISBN-13: 978-1910323625

As long as a match stays alight. As much as you have time to see in the room that flares and fizzles out. The images holding, briefly, then fall. Some lines you manage, they are gone, another match, again. Pieces missing, empty pages, match, again. An alien sentence comes and sticks in your mind.

Z213: EXIT p. 23

Reading Z213: EXIT by Dimitris Lyacos you feel like the book’s anonymous narrator. Every page of the volume is a flaring match and for as long as it lasts it reveals before your eyes a fragment of hell. There are no cast-out angels here, rivers of blood and lava, lashes and cauldrons. Lyacos’ hell is a valley of transmutations right to the point where the match has gone out and identity, memory and existence are lost. The soul’s bone has broken and circulates like a clot in the body, the body nevertheless remaining unchanged. We are many souls inside one and only leathern bag: was this not, among others, the “lesson” we learned from tragedy? If, however, ancient tragedy shows us that the body pays with its disintegration for the emergence of personality and its right to pursue desire, the contemporary tragedy that Lyacos portrays reveals to us a human subject that can no longer focus on its centre of gravity. How many different winds blow inside Aeolus’ goatskin? The protagonist of Z213: EXIT appears not to recognize his own voice. He does not remember where he is coming from, where he is going and his name is hidden under a series of names.

Make a point of remembering to write as much as I can. As much as I remember. In order for me to remember. As I keep writing I go into it again. Afterwards it is as if it were not I. How do I know that I have written this. Faded, someone else’s words. My own handwriting though. From a void I wake up within, time after time.

Z213: EXIT p. 61

Z213: EXIT is, as far as narrative order is concerned, the first part of Poena Damni. It was not the first of the three to be published, however, and it has been revised for the present edition (Shoestring Press, 2016). The second part is With the People from the Bridge (again a re–working of a text that had been previously published under the title Nyctivoe), while the place of epilogue is taken by The First Death (Shoestring Press, 2000) which was the first of the three works to have been published. The intricate publication history shows that the overall work follows an non-linear development. There are different characters present in each book, a general impression is given, however, that an overarching narrator is in control of the story. The protagonist of Z213: EXIT may differ from the suffering man of The First Death, yet there is a consistency in scope, a relentless effort to face “The Real”, which forms an inextricable bond between the three texts. From a narratological perspective, while different characters come and go, a Narrator seems to be there at all times and there is an impression of “unity in difference”. Many voices, one underlying tone, one – fragmented – Logos.

A third person account introduces the character in The First Death:

[…] body swept here and there on the rock like seaweed or a lifeless tentacle, fruit of a womb ship-wrecked by the winds, ensanguined and flesh-filled mire. The left arm cut short, the right to the end of the forearm, a rotted stick raving amid the water’s lungs.

The First Death p. 9

In Z213: EXIT, however, only first person accounts are involved. The Narrator seems like a confused man, at least on a surface level: he does not know who he really is or where he is going; the trilogy makes use of different genres in each individual volume – a fragmented kind of prose in Z213: EXIT, a sequence of theatre monologues interrupted by stage-like descriptions in With the People from the Bridge, and, finally, a dense poetic idiom in The First Death. As the story unfolds the Narrator reads the notes of others inside his own diary, he does not recognise his writing, he is stranded on an unknown island; he speaks through so many voices that you wonder in the end if he is one or many. His agony is “the infectious agony of butchered machines” (The First Death p.29). This fragmentation of the subject which leaves the protagonist of The First Death mutilated and abandoned on an island, as if he were the ruin of a text erratically washed up on a page, builds up an inescapable angst. We cannot but remember Karl Jaspers, in his analysis of the tragic phenomenon, who mentions “the shipwreck” as “a boundary of the human process”. In Lyacos the traditional opposing values that set in motion the tragic fall do not stand against each other, yet, there is a collision of a different order which has the form of a powerful wind chiseling a rock. Lyacos’ writing, is a sequence of variations describing the gradual history of an archetypal fall: an ancient “Homeric hero” becomes a wreck of a subject, an artificial, discontinuous and light-weight ego. The textual development leading up to this is full of tensions, codified, hyper-mythical (in the sense that it exhibits a revelatory power that divests itself of symbolism), showing “forms in themselves” and leading up to ritual practice. At the end of |Z213: EXIT the Narrator takes part in the slaughter of a lamb. The festival of Easter comes to mind, as well as the Exodus of the Israelites:

He was the one who had filled it from the lamb’s blood, in the beginning had first let it run, a basin then underneath when the pressure eased off, in the end what was left, back into the pit which blackened and drank.

Z213: EXIT p. 143

The likeness with Nekyia – Odysseus filling a pit with black blood from the throats of the sheep so that the ghosts in Hades gather about him – is obvious. In Poena Damni, nevertheless, myth should not be taken to refer to an intertextual or structuralist background, a secret blood ritual common to all the stories. The revelation here relates to the brutality of the image and its projection through a fetishism of the object-word. Blood. Pressure. Blackening. Myth, in Lyacos, does not present itself as an organic whole upon which his writing is articulated: Z213: EXIT is not a new reading of the myth of Odysseus or Moses. Lyacos does not construct a new myth either. What he does is to turn the myth inwards, towards its deep structure, emphasizing the basic constituents without the intervention of a constructed plot. The words of the trilogy are the fragments of the echo of a primordial explosion, which, if you fit them together, compose the innermost name of tragedy; Sacrifice. Altar. Sacrifice. Odysseus. Sulphur. Dredger pain. Angst and guilt. Poena Damni is the name given to the pain of loss, the pain of the damned, those who have been sentenced to Hell, the utmost emptiness of their feeling, the realization that they will never again feel the warm touch of God. This is the ontology of the tragic phenomenon: vast separation from the light that would lead us back home. And here, a notion of some present-day sublime can be foregrounded: The subject cracks before the impermeability of language and ends up shattered on its walls. The Narrator’s multiple transformations of speech in Poena Damni, his inability to feel a little warmth, his angst and despair, are the result of the mass of the sublime which is behind the “curtain” and pins us down with its weight.

In conclusion, Poena Damni is a post-tragic work. Certainly, it does not follow from tragedy, if tragedy is intended as an ensemble of formal characteristics, but unequivocally describes the tortured and tragic fall of the (post)modern subject: A person made of one thousand screams whose core of being has broken apart and is spread out like an archipelago of anonymous islands on a vast empty surface.

Ilias Bistolas was born in Athens. He specializes in theatre and literature criticism and is a regular reviewer for a number of Greek magazines.

As Fate Would Have It

by

James Jordan

It was the first anniversary of Jake’s death. In the morning he’d been standing on his front lawn reading the L.A. Times when a Chevy Suburban jumped the curb. Jake – his head shaved, his bearing military, his athleticism at 62 (we were evenly matched in tennis), in one of his elegant suits, a contrast to the earring he wore like a pirate, he said, to instill fear in his enemies – in perfect health during the last moment of his life, had no way to know he’d drawn his last breath. He was here, and then, in a heartbeat, he wasn’t.

The day before Jake was killed, we’d filed an amicus curiae brief in the Eleventh Circuit supporting the Patient Protection Affordable Care Act, the Obama healthcare law. That evening we talked about it in my office, sitting on antique armchairs, a gift from Beatrice, my ex. Each chair was crowned with a carved cornice framing a cameo: one of the Queen, the other of her prince.

“That’s us,” Bea had said, “Victoria and Albert.”

Tempus fugit, I thought, looking through the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office that were meant to provide views of Los Angeles, white sands from Malibu to Huntington Beach, the cliffs of Palos Verdes, Santa Catalina Island, and the sun sinking beneath the Pacific with a flash across the spectrum of light reflecting on calm waters, the last breath of day heralding the falling night, but as usual, at sunset, all I could see was smog.

In one hour, in the Jacob Marley Memorial Conference Room on the floor above mine, I had a meeting to negotiate the final terms of a multi-billion dollar, multi-bank loan to finance the construction of a transnational undersea fiber-optic-cable network. I directed phone calls to voice mail and locked my office door.

I’d made a New Year’s resolution, still unfulfilled, to resume dating. There was no connection between Jake’s death and my subsequent self-imposed solitude, they were unrelated events occurring, coincidentally, with near simultaneity. To think otherwise would require psychological analysis, the words meaning literally, an examination of the soul, a province of faith, the work of theologians; for the rest of us contemplation of this sort is likely to obscure reality and very unlikely to be worthwhile.

Once, early in our relationship, after we’d received a counter to a client’s offer, Jake had said, “Georges, what do you think they really want?”

“If we question their intentions,” I’d said, “we’ll never close the deal because there are infinite possibilities.”

He settled into his chair, his elbows resting on its arm, the corresponding fingers of his right and left hands touching at their tips, forming the shape of a steeple. “How does a former graduate student of divinity,” he’d said, closing his hands with his fingers entwined, “become indifferent to allegory, immune to allusion, become a man who says he’s never met a stereotype or a cliché he didn’t like?”

His confusion escaped me. Life is short, its quality fragile, and so the imperative to seize the day should be self-evident. People who understood this invented stereotypes, people like me, people who didn’t have time to kill or a moment to lose. I don’t have to reinvent the wheel to know how to talk to a postal clerk in a bad mood or a cop who’s pulled me over. And I eschew subtext like the plague. Not only does superficiality foster efficiency, it reduces the risk of opening old wounds.

Stereotyping made me reluctant to try Internet dating. If my friends got wind of it, would they think I was unable to weather a sea change? But if I couldn’t find a woman to date, figure out how to begin a new relationship after a failed seventeen-year marriage, would they think I was unable to navigate the perfect storm of my personal life?

Jake had encouraged me to try Internet dating, and so on this auspicious day I logged on to LADating.com. I uploaded recent photos and was instructed to complete a profile, to approach the task as a labor of love, to blow my own horn, to cast my bread upon the waters.

It was right up my alley— with one caveat. As a corporate lawyer in a white-shoe firm, my stereotype served me well because my adversaries assumed they understood who I was and what I wanted, an advantage worth its weight in gold.

But I didn’t want my corporate-lawyer stereotype to lead me to the wrong kind of woman, one who didn’t share my values. So I began by writing about my politics, saying, “If you’re a neocon or a retro-con, if you’re okay with tax cuts for the super-rich, global warming, underfunding education, overturning Roe vs. Wade, or any other right-wing agenda, please don’t waste your time or mine.”

Answering the other questions was duller than dishwater – Should children be seen and not heard? Do you prefer sex with the lights on or off? I was ready to cut bait and bail but I saw the light at the end of the tunnel: only a few questions remained. I said that my son, Dante, in the twelfth grade, lived with me, that I wasn’t religious and wasn’t looking for a woman who was.

I was done. The program sent me the profiles of women that matched mine.

Thirty minutes before my meeting, I dived in.

A schoolteacher was first. She had gorgeous red hair and her similes were Homeric – “Feeling sad because my husband left me would be like crying over spilled milk. It’s water under the bridge” – her prose replete with phrases that rolled off my tongue like water off a duck’s back. We were kindred spirits. But I just didn’t like the cut of her jib.

The next woman was a lawyer, like Bea. I moved on.

Grace, an aerobics instructor, was looking for a man to make her feel weak as a kitten.

Bunny, a widow, was the C.E.O. of her family’s charitable trust. Her given name was Rachel but her grandmother had called her Bunny. She was fifty, two years younger than I, but didn’t look older than thirty-five, prompting me to wonder if she’d honored the recent-photo rule. Her face lacked symmetry of perfection, one eye drifting to the right, her nose too large, her mouth too full. In one photo she wore running shorts. I was riveted by her legs.

I brought up the next profile but couldn’t concentrate, so I went back to Bunny’s. She wasn’t like Beatrice. Bunny had wavy brunette hair; Bea had tight strawberry curls. Bunny was tan; Bea was pale. Bunny’s stature contrasted with Bea’s petite frame.

How did I overlook her comments about religion? I didn’t have time to read her profile word for word. My meeting would begin in ten minutes. If I didn’t write to Bunny then, I probably never would. If what she’d said about religion had registered, I never would have contacted her, not because religious experience renders the mind shallow but because Bunny, like Bea, was Jewish. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

I waited for her at an outdoor table at a café in Brentwood. It had rained earlier, leaving the taste of the air afresh with possibility, its scent sweetened with the aroma of roses, heliotrope, and lavender displayed in front of the floral shop next door.

Walking toward me on a sidewalk along San Vicente Boulevard, leafy coral trees grown tall in the majestic median, purple blooms of Jacaranda littering side streets, Bunny stood out: confident, regal, stunning in a double-breasted red raincoat. She had the visage of an angel; her photos had been unjust.

When I rose to greet her, she said in her Germanic accent, “Let’s not talk about anything routine.”

“What’s routine?” I said.

“Oh, you know, the weather, the war on terror, work.”

Boys on skateboards, no older than Dante, zipped by.

“I see your point. When it rains, it pours; war is hell; work like a dog, sleep like a log.”

That broke the ice. She laughed. “How did you meet Beatrice?”

“She was a litigator; I was a transactional lawyer at the same firm.”

“Harold was a lawyer,” she said.

“How did you meet?”

“Don’t you think it poetic,” she said, “that a girl named Bunny landed a cocktail-waitress job at a Playboy Club? That’s where I met Harold. I was his bunny.”

Two months later I wasn’t sure where the relationship was going but it was going well. Bunny took Dante and me to see the Dodgers play the Giants at Dodger Stadium, surprising and delighting us with her fluency in baseball history. By that time, I knew she was Jewish. Jake would have scoffed at my superstition, but I wondered what he’d have said about her continuing refusal to talk about the weather, the war on terror, or work.

When I spoke to Bunny a few days after the Dodgers’ game to confirm the time I’d pick her up that evening, she said that she’d stopped dating other men. I was a single dad with a never-ending workload, so I hadn’t dated anyone else, but still, I was surprised, not so much by her decision as by her telling me about it because I’d done nothing to initiate sex and neither had she. Was she saying it was time for that to change? I quickly abandoned the thought, a textbook example of how possible subtext can lead to misunderstanding.

Then Dante called.

“What’s up, Champ?” I said.

“Mom didn’t show up at track practice,” he said. “Again. She’s not at work, not answering her cell. Dad, will you buy me a car?”

I bit the bullet and called Bunny to ask for a rain check.

“Dante can come with us to dinner,” Bunny said.

“He has final exams in a few weeks,” I said.

“It’s strange she would forget to pick up her son,” Bunny said.

“When Dante was in tenth grade – this was about a year before she left us – she didn’t show up for the science fair, where Dante’s project was in contention for first place. Dante was upset and I was furious. Later, I said to her, ‘you love your job more than anything else. More than you love us.’ She said it was true.”

Bunny insisted that our next date be dinner at her house. When I arrived, she was wearing a low-cut blouse. I was careful not to let her see me looking at her chest.

In the kitchen, she worked on a tiled countertop, her back to a center island with six gas burners and an array of radishes, red peppers, and spinach. Shredding cabbage, she spoke of Harold’s cancer, painting the details – the regression of a robust man into a vegetative state – with painful precision.

“The tumor crushed his brain,” she said, using a paring knife to julienne carrots, “and that was tragic because he had such a fine mind.”

An aroma of oranges and caramelized onions wafted from a saucepan. A chart titled “Fruits and Vegetables with the Highest Anti-oxidant Capacity” was taped to her refrigerator.

The countertop tiles were Navajo white with the exception of a pair of repeating distinct decorative tiles set randomly but always in tandem. The image on one was the Greek goddess Themis, holding the hilt of a sword in one hand, the scales of justice in the other. The image on the other tile was a serpent entwining the staff of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine and healing, a kitsch touch to an otherwise exquisite décor.

“Imagine,” she said, carrying carrots to the center island, “seeing someone you love suffering metastasizing sarcoma in the parietal lobe.”

As she moved to inspect the saucepan, her breasts brushed against my back as I diced a red pepper.

“Damn it,” I said. I’d cut two fingers.

She pressed a towel against the wound. “Hold this.”

She soaked my hand in a bowl of hot soapy water, rinsed it, poured hydrogen peroxide over my cut fingers, dried them, and wrapped them in gauze. She secured the gauze with surgical tape.

“You were right there for Harold,” I said, “picking up the medical jargon.”

She looked at me, her face inscrutable, tension mounting until a pot boiled over. She turned off the gas burner.

“I didn’t learn medicine from Harold’s doctors. I’m a surgeon,” she said.

“But you said you’re the C.E.O. of your family’s eleemosynary foundation.”

“I am,” she said.

She wiped the blood-soaked peppers off the cutting board, cleaned the knife, and went to work on a new pepper.

She said, “When I began Internet dating my profile said I was a surgeon. The only men who wrote to me were other doctors and hypochondriacs.”

“What was wrong with the doctors?” I said.

“They weren’t emotionally expressive. Know what I mean?”

“What else did you expect from a doctor?” I said.

“You know, I’m a fierce advocate of healthy ingredients,” she said, the knife pointed at me, rotating slowly.

“I’ll finish the radishes,” I said.

“You’ve spilled enough blood for one night.”

“Lacking emotion isn’t bad,” I said. “I wouldn’t want someone who was emotional cutting me open.”

“Will you pour me a glass of wine?” she said.

With my bandaged fingers, I fumbled with a corkscrew.

“You can never eat enough veggies,” she said. “The trick is to steam them lightly to enhance digestion while preserving the vitamins.” She arranged steaming broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts on a platter around an oval bowl of wild rice.

As I eased the cork from the bottle, I said, “With a doctor, what you see is what you get.”

“Is that so, counselor?” she said, covering the vegetables-and-rice platter.

“Don’t get me wrong,” I said, pouring two glasses of Sauvignon Blanc. “I like them.”

“How many?” she said.

“How many what? How many doctors do I know or how many do I like?”

She sipped the wine. “Shall we put the bottle on ice?”

“I represent medical organizations. The American College of Surgeons for instance.”

Her face softened. “That’s interesting. What do you do for the ACS?”

“Tax advice,” I said, “nonprofit compliance with IRS regulations.”

“Do you advise the ACS Political Action Committee?”

“You’ve changed the subject,” I said. “We’ve dated for two months—”

“You know,” she said, “it’s taken three-and-a-half months for us to find the time for me to make you dinner. What a shame.”