Walker Elliott Rowe's Blog, page 5

January 26, 2017

Medical Marijuana in Chile

26 January 2017. Viña del Mar.

In this post we explain the current status of the law in Chile regarding medical marijuana. We also explain how you can get a prescription for marijuana in Chile and where you can join a club to buy that.

In short, in Chile it is legal to smoke and grow marijuana for medical use. It is not yet legal for recreational use. That bill was approved in and has been stuck in the lower house of congress for some time waiting to be sent to the Senate. Still, there are more than 500 marijuana seed shops just in Santiago. It is legal to possess marijuana but the terms of that are not clear. For example the law says it must be for “immediate consumption” and that it is for “personal use.” But the law does not say where you are supposed to obtain marijuana. Growing marijuana here can cost you 5 years in prison.

In Chile, President Bachelet approved Decree 84, allowing the use of marijuana for medical purposes and made changes to the law 20,000 as well.

Also an actress, Ana María Gazmuri, started the organization Fundacion Daya to lobby for changes to the marijuana law. Now they are also one of the organizations you can go to to get a prescription for medical marijuana. They also have a large marijuana farm where they produce 1.5 tons of marijuana per year.

Daya is also supposed to be working with the pharmaceutical industry on finding, producing, and distributing cannabis products. Pharmacies are allowed to do that here. But no one trusts the pharmacies, because they have a history of price collusion and already costs the citizens plenty. No pharmacy has stepped forward yet to sell marijuana. Regular marijuana obviously is lower priced than whatever product a pharmacy might produce.

Municipal Marijuana Farms

A few years ago one of the mayors of one of the largest communities in Santiago applied for a permit with the agriculture department to plant a large amount of marijuana. The goal was to produce hash oil for epilepsy, cancer, and other patients. The mayor said the government never responded to his application. So the mayor said it was approved by default. Now there are are many large plantings of marijuana in the country.

Where to Get a Prescription

Dr. Sergio Sánchez Bustos is one of 4 doctors at the Fundacion Latinoamericano Reforma. They write prescriptions there for medical marijuana. The doctor told me that there are only perhaps 10 doctors in the country doing that now. But that number is certain to grow as word gets out.

A visit to the doctor costs 25,000. There is no formal list for what illnesses marijuana is allowed. For example, Dr. Bustos will write prescriptions for chronic pain and anxiety. So it is not just restricted to people with epilepsy or cancer.

Where to Get Marijuana

You can grow your own or you can buy marijuana by joining one of several clubs. Two in Santiago are Green Life and Dispensario Nacional. There are others, like FASIMC. As of January, Green Life had a waiting list. Dispensario Nacional has no waiting list and says in 6 months they will open a branch in Viña del Mar.

Their prices for marijuana are 7,000 to 8,000 CLP per gram. And membership is 25.000 CLP per month. You can only get buds (flowers) there and not oil. The owner said only a pharmacy is allowed to produce oil. We just said the big pharmacies are not producing cannabis products. So I am not sure who is doing that. I do not know where Dispensario gets their marijuana, but they say they buy from a grower who has a license from the agriculture department. I do not know if their marijuana comes from one of these large plantings allied with Daya and the different towns. Or it might be that they are growing it themselves.

The dispensary has an office in a skyscraper in Providencia. The point being it is in the open and not hidden away. And Dr. Bustos’s office is right next to the capitol of Chile.

Marijuana is free for those who are working through the La Florida municipal pot farm. But I am not sure how one signs up for that.

January 15, 2017

Safe Beaches and Swimming Safety and Rules in Viña del Mar, Chile

It’s summer here in Viña del Mar. It is a cold 65F (18.3C) and water 61F (16C) today (15 Jan 2017). But in the sun the weather is like San Diego: spectacular and comfortable to sit in the full sun without getting hot. Often it is cloudy or foggy here. We have the same weather as San Francisco, but with 30% fewer sunny days.

Swimming Advice and Sources of Safety Information

Here are some rules about the beach in Viña del Mar, or rather advice, since there are no rules.

And some sources of info, like these links for those going to the beach and in the water:

Weather

Water temp

Ships in harbor

Marine forecast. And in Spanish.

Emergency Information from Minister of Interior

Why Don’t Chileans Swim?

Chileans are afraid of the water. Argentinos too, although they are better swimmers, having more access to pools, and the Atlantic Ocean, for those living in Buenos Aires.

People are afraid of the current here and they say the water is too cold. So almost no one swims. Yet, the water is comfortable for swimming. It might be cold relative to Florida. And there is no current in most places.

It is cold. But it is not the arctic, although the Humboldt current flows from there. The water in summer (Dec-Feb) is 61-65 F (16C -18C), which is cold. But the secret is not minding that it is cold. Either that or go to The Dominican Republic. But there is a lot to be said for swimming where you are standing. Faced with that dilemma get your fat ass in the sea and don’t whine about the cold.

When I go to beach, I am usually the one one swimming beyond the breakers. Sometimes another person will swim out. And there are a couple of groups of people who exercise together and swim out into the shipping channel. It is only dangerous when there are mareas (high tides and tidal storms that march across the Pacific) or when there are fragatas portuguesas (man of war jellyfish) in the sea. In the mareas (which really just means tide) the waves get large and splash into the streets. The breakers aget frighteningly large. Do now swim in the marea. As always when a wave approaches you dive under it so it does not crush you. Do not let it knock you down.

Which Beaches are Safe

In Spanish it says “apta para bañar” (safe to swim) on the post where they put up the red (no apta para bañar) or green (safe) flags. If the flag is red you can swim anyway. Just swim like you won’t drown and the lifeguards, where they have those, will not bother you like the do in the USA, unless you swim really far out and look like you do not know how. I swim far off the beach and around the rocks. They do not bother me because, having grown up at the beach in a boating family, I am a strong ocean going swimmer. A large part of Europeans and Americans I think would be too. Chileans have fewer swimming pools than Americans. So many do not know how to swim.

Playa Abarca

The beach next to the Sheraton is apta para bañar. It is roped in and there is a guard. It is the working glass people who go here and not the quikos (upper class Santanguinos.) Fine beach. I swim out to the ropes, far off the beach. Other people do that. One time a gung-ho concessionaire who takes people out in a jet ski came to check on me and another guy swimming at the rope, way out there. He ran into to me. I told him to go away. He carried the other guy back on the jet ski. But there is no current. It is not deep. It is safe. It is a bay, with large waves, but without ocean currents.

Playa Las Salinas

The beach in front of the Naval College is the most sheltered, safe, and is small. Get off at the bus stop right in between the college and the big rock on the coast and it is a little harbor with rocks on two sides, thus there is no current. Safe for kids, if they are not too little.

The Playa Acapulco

This is in front of Starbucks and north of the casino. It is not apta para bañar. But that is silly because there is no current and the water is not deep. The whole bay of Valparaiso is safe to swim, except Renaca faces the open ocean. So the waves are bigger there.

Con-Con

The beach at Con-Con is the point where the Aconcagua River enters the sea. It is more of a shallow bay that beach. But it is fine for swimming. Lots of surfers there.

Why are there no boats here?

There are no boats in the water here too, although it is legal and you can get a fishing license (I have one). You need to take a test to get a license to pilot a private boat. You take classes from the Navy in Valparaiso. I signed up for that.

The only recreational boats you see here are sailboats. Once I saw a jet ski. Once. In San Diego you can walk across the bay without getting your feet wet.

Here are the emergency phone numbers. For the police, dial 133. For marine rescue, dial 137 on your cell phone.

In truth, the beaches of Viña del Mar are safe for swimming for anyone who swims well. There is no current, since the region from Renaca to Valparaiso is a bay, shielded from ocean currents. That said, the beach at Renaca faces the prevailing winds and the waves there are too large for children and people who are not strong swimmers. Any other place anyone who can swim should feel safe doing so even if no one else is swimming (or practically no one, as some people do swim, a very few).

There are lifeguards. They wear yellow vests. They might blow the whistle if you are playing near the rocks. They do not bother anyone like they do in the USA. Some are handsome blond argentina guys talking up the girls in bikinis.

January 1, 2017

Standing Female Dignitary (Hillary Clinton) in the Form of a Pre-Columbian Whistle

by

Marit MacArthur

thumbnail illustration by Rene Castro

From the outposts

of Lovemaking and Motherhood

she advanced, a vessel

worked into the desired form.

No slenderness to the waist,

her feet are gone beneath

the long heavy dress of terracotta

sun-baked, kiln-fired,

stitched with nails.

Slack chin, hawk nose, high

cheekbones, eyes half-closed

in an easy smile, all

beneath a uniform

powder mask.

A giant brooch clasps the cape

to draw the eye away from

spent breasts. She’ll ring if lightly

struck, her iron-rich reds

oxidizing blue, hands held up

in supplication or defense.

Visible from the crowd, giant spiral

earrings match the coiled headdress,

itself the mouth-piece of the whistle,

her hollow body the resonant chamber.

Puffs of air split by the fipple

pierce the composure of the other

dignitaries, who all outrank her so far.

After the strictly ceremonial

peace talks, she follows them

back to the palace.

Author Bio

Marit MacArthur earned a B.A. in English and creative writing at Northwestern University, where poet Mary Kinzie changed everything. She went on to earn a Ph.D. in English from UC Davis and an MFA in poetry from the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. Her poems and translations from the Polish have appeared in Southwest Review, Leveler, Front Porch, Jacket2, American Poetry Review, Watershed Review, World Literature Today, Verse, ZYZZYVA, Peregrine, the Levan Humanities Review, and Airplane Reading.

December 16, 2016

Infelicitously

by

Patricia Dale Decker

thumbnail drawing by Rene Castro

Orphy asks if she can pee on you. You stop kissing her neck.

The movie theater is small, so you see most of the people sitting around. The girl from high school is being fingered by the grocer down the street a few seats away. Her head is leaning back and her mouth is open almost to a moan. Two rows down is Orphy’s little sister, Jenny. She’s sharing popcorn with sticky fingers, Matt. He’s shorter than her, dumber than her, not worthy of her. When he got into the car earlier, he only greeted Jenny’s breasts. They were squeezed tight and her blond hair was stuck in her armpits. She looked at you in the driver’s seat, and showed her gums. Everything she says is accompanied with a smile. She makes cocoons turn into butterflies.

You’re wondering if Orphy is joking so you don’t retract from her soft skin, smiling instead against her ear. You haven’t done this in a while, so you lightly wet the lobe the way she likes it. You try to amuse her, say that you really need to get rid of that burn from that jellyfish earlier. She doesn’t laugh. Her body doesn’t move. You take your tongue out of her ear.

“You’re a fucking asshole,” Orphy says, staring ahead. The colors of the movie are lights on her face. They flicker blue, green, white as her eyes stay small and serious. You straighten up.

“Alright, when?” you say.

She says she wants it tonight. You nod slowly, hoping that if you nod enough she might change her mind.

For the rest of the movie, you’re trying to decide if you should go relieve yourself or not. It was a lot of Pepsi. By the end of the film, the urine has absorbed back into your body and you feel good. The Pepsi has become you. Orphy is now licking butter off her fingers. Her sucking is slow, meticulous, as if her pores have digested the oils and now she must give them a taste. The movie ends quickly as you watch her. You take Orphy’s hand out of the theater to leave. It’s stiff but holds on nonetheless. She’s been holding on ever since you met in college. Jenny follows the two of you out with her little bitty boyfriend. He’s full of braces and blue balls he doesn’t know how to use. Not on Jenny for sure. She’s ahead of all of them. Jenny’s got the same small eyes as Orphy, but they’ve sprung on her sooner. This goon might just be for practice. She wants someone older, she’s even said it. She’s winked at you before, too.

You’ve had conversations. Most of them were brief, and unfortunately taken up by Orphy. Jenny would be talking about what she wants out of life and how all the guys are idiots.

“I feel like I’m ahead of everyone, my friends, everyone. The teachers at school are just holding me back with stupid reading comprehension! I can’t wait to get out of this shithole. I’m going to travel the world,” she’d say.

“It’s about living so that when death comes, you’re not afraid,” you’d said.

She’d think that you’d said something spectacular. She’d then give you a hug and say thank you for listening. Orphy would stand over the kitchen counter, adding herself to the conversation when she didn’t have to. She’d tell Jenny that thirteen is probably the most confusing time in someone’s life. As she was speaking, you’d have to remind yourself that two years with the same girl meant something, that a new girl would end up being an old girl in no time. When you first slept over at Orphy’s house, her parents were out of town as always. Jenny was there in the morning. She came out of her bedroom in her pajamas, no makeup. She shook your hand limply and offered breakfast. Orphy left to work and Jenny stayed to make an omelette. She asked if you were picky. You’re never picky. She spoke about the guys she liked at school and you told her she could have anyone she wanted. She shrugged, not yet aware of the power she held as a woman. You shared music, she made a playlist, she said that Orphy loves you. Jenny hasn’t made a playlist since then. When reminded she says she doesn’t have the time. You always hug goodbye. Maybe she feels it too.

You drive everyone to their place and Orphy puts her hand on the inside your thigh. It’s warm and you’re small. You’re thinking about bed, but also about the inevitable urine festivities. Is it for consumption or piddling? Should you stop by somewhere for funnels? You think of these various possibilities as Orphy’s hand glides expertly north. You look at her, and she’s calm. She is looking forward as always. You haven’t been able to finish with her lately but you’ve heard of the two-year-itch. It’s supposed to go away. You use all the positions but perhaps you’re about to learn a new one. Orphy’s hand is working in deeper to your crotch now. You switch lanes and catch Jenny’s eye. She’s there in the back with Matt. He’s looking out the window and she’s looking at you in the rearview mirror. Her eyes are deep brown, and getting darker with every intersection. They could take over mind and bone. You feel Orphy’s hand make firm contact and you get hard, rubbing into it. You slip your finger inside Orphy real quick but Jenny looks away and once again, you go soft.

Jenny’s play pal is dropped off in the west end of Barry. She doesn’t get out of the car to say goodbye. Maybe she was only giving him a chance, and he blew it. You arrive at Orphy’s place in the city and the girls lead the way to the door since her parents are out studying animals in the islands. They never go into it. Jenny says goodnight as soon as you take your shoes off. You follow Orphy upstairs to her room. She lies down on the bed and asks you to take her before the door is even closed. You do, anyone would. You hear Jenny getting ready for bed down the hall, her favorite song is on. Orphy stops rubbing your crotch and asks you if you think she looks beautiful. She kisses you with lips wet with frenzy. They’re thin, and so are her legs. But you don’t get any harder. She’s trying to be playful and lifts her skirt up to show you her panties. You’ve seen them before and you’re exhausted to see them again. She tells you to meet her in the bathroom. You ask her why, what for. She gets all serious and tells you to stop fucking around. She stops at the door and turns back to you.

“We need this. You know that we need this.” she says. Her eyes are sad.

You hear the shower start to run and you think you might as well see what Jenny is doing down the hall. Orphy is probably shaving her legs, between her legs, she needs a few minutes. You’re not sure if this is what you need, the both of you. A golden shower is not something you had in mind, you want something completely different, something that makes you giddy again.. Maybe Jenny wants to chat while her sister prepares to pee on you in the shower. You past the bathroom and walk up to Jenny’s door, looking inside, she’s brushing her hair. She’s got her preppy pajamas on. Pink plaid. Her face looks up as your knock startles her.

“What are you doing here?” she says.

You say that you just wanted to chat, you point to her collage of friendship photos and ask who they are. She tells you. She sits down on the bed with her legs crossed. You join her with your feet flat on the floor, the ground is the only thing you can feel anymore, the rest of you is floating. Her hair is covering her cheeks and she’s looking up at the ceiling. She asks you where Orphy is, if she’s gone to sleep. Maybe she’s hoping Orphy is asleep like you are.

“Jenny, you’re something special.”

“You really think so?”

You feel her gravitational pull, the way her body is leaned towards yours tells you she needs the excitement. You wonder if this is the moment things change. Maybe this is the moment that life becomes a little more important. Maybe life is made in the mistakes.

You lean into her hair, and bring the strands behind her ear. You kiss her soft cheek and she still hasn’t moved. She must be a little shy, she needs your expert hand to lead the way. You take her chin and bring it to touch yours, your eyes are closed but you find and kiss her chapped lips. She doesn’t kiss back. Upon looking at her face, you see tears rolling down.

“Please, please stop. Oh my god please just stop,” she says.

You feel your heart leave your chest and drop to the floor. You ask her why? Isn’t this what you wanted? I think I love you. Don’t you love me? She’s sobbing now, shaking her head uncontrollably. You say, Maybe it wasn’t Orphy all along, maybe we’re meant to be together. Don’t you feel it? She’s shaking so hard she might fall over. You get up, confused, not sure you should be here anymore. Maybe she needs a minute to figure it all out. You go to go to the door and there’s Orphy, standing with a towel around her naked body. Her face looks disoriented. The water from her hair is making a dull sound as it creates a puddle at her feet. Your stomach hurts, or maybe it’s your bladder. It feels like appendicitis but you’ve already gotten that taken care of. You have to pee badly. You say you have to go, but it comes out in a mutter and Orphy starts screaming.

“What the fuck? What did you do?” Orphy says. You stammer in a lack of response because your tongue has melted down into your throat. You hold your stomach, and feel it’s expanded.

Orphy goes to Jenny and touches her shoulder, “Jen, tell me. What did he do?” She sees how hurt Jenny is, how she can’t explain herself. You’ve never seen her like this.

“He…he…I’m so sorry Ophelia.” Jenny says. She looks up with swollen eyes.

“Did he touch you?” Orphy turns to you, “Did you fucking touch my sister? You did, didn’t you. I knew it. You’re disgusting.” She turns away from Jenny and steps in front of you.

“I’ll call the fucking police.” She says.

Jenny cries harder and you’re just standing there, staring back at Orphy, not sure of what to say. You realize, there’s nothing you can say. She starts screaming at you, calling you a pervert, calling you all these things you haven’t ever seen yourself as. You wonder what the police would think, if they would actually side with Orphy. You guess yes, it’s their word over yours. You mean nothing. She tells you to get the fuck out. She holds her little sister and tells her it’s okay. You leave your jacket, you leave your shoes. You run downstairs to that front door without being escorted as you run to your car you’re thinking: how could you have ever been this wrong.

Author Bio

Patricia Dale Decker is a Canadian-Russian writer living in Santa Monica, California. She holds a BFA in Writing from Pratt Institute and is currently working on a debut novel.

December 3, 2016

Three Poems by Don Thompson

Incident on the Road to Tupman

by

Don Thompson

thumbnail artwork by Rene Castro

A fledgling dove just above me

concealed among pistachio leaves

panics as I walk by,

trespassing in a corporate grove.

Startled, I share with her

the fear so close to us all—

bird and man

and the orphaned infant coyote

I’m following with a cup of water.

Thin and ephemeral, frightened,

with no hope of survival,

he keeps dancing away from me.

Sad. But that wingtip

flicking the back of my neck

has reassured me somehow,

though there are no words to say why.

Competing for Apricots

A crow fatter than a pullet

with a beak like a case-hardened chisel

perches on a fencepost:

You can tell how self-assured he is,

how he takes on life with élan,

knowing he will be fed

in this world of unlimited insects,

roadkill replenished every night,

lizards dozing in the sun,

and rumors among the corvids

about this summer’s first ripe apricots.

I’ve been watching that tree myself.

Night Music at Deep Wells Farm

Only an owl, of course,

and not somebody alone in the dark

who has come across an odd flute

and breathes into it without much skill—

the fingering too hard to learn,

the simplest tune elusive.

But whoever it is keeps sounding,

again and again, compulsively,

the only note no one wants to hear.

Author Bio

Don Thompson is the current (and inaugural) Kern County Poet Laureate in California. His books include A Journal of the Drought Year, Local Color, Everything Barren Will Be Blessed, and Back Roads, winner of the 2008 Sunken Garden Poetry Prize. He was born in Bakersfield, California, and has lived most of his life in the southern San Joaquin Valley, which provides the setting for most of his poems. Don and his wife Chris live on her family’s farm near Buttonwillow in the house that has been home to four generations. More of his work can be found at http://www.don-e-thompson.com/

November 17, 2016

The Smoker

(after Rufino Tamayo’s painting El fumador, 1945)

by

Matthew Woodman

artworth by Rene Castro

You can tell a man

by his brand

of tobacco

does he profess

hold forth

extol his exploits

understudy

to the great man theory

a prince among

rolling papers

you would plot a coup

had you wherewithal

confess

the bulb swings

consider this conscription

allot yourself time

enough to curfew

to post bail

do not break

character

wait for the check

nod

check

excuse me

check

can I have

the alibi

Homage to Juarez

(after Rufino Tamayo’s painting Homenaje a Juárez, 1932)

by

Matthew Woodman

artwork by Rene Castro

when to tear it all down

when to ignore lanes

when to disenfranchise

detassling corn a familiar sun

to sell time the humidity

mosquitoes the worst blood

maintenance such structure

to follow but why such control

but how all eyes and ears

to advocate to climb

means your honor I object

overruled from within

systems of ammunition

catechism curtailed

even the interventionist

creditors excised respect

for the rights of others

is peace given no one must

institution one must

concentrate on most likely

to be exploited may those

who would take advantage

who would close doors

find no commuted sentence

Homage to Zapata

(after Rufino Tamayo’s painting Homenaje a Zapata, 1935)

by

Matthew Woodman

artwork by Rene Castro

What have you done

with my hat chingόn

que mierda this bust

they trot out to restore

the populace reassurance

no peasants no indigenous

that it’s all in the past

antique a campaign

ha those days are these

their angels use wires

they concentrate their inner

wealth circles compounding

interest they may follow

a scorched earth policy

we will not be led we will

not be display you can head

in the plaza exhaust

your tenure will choke

your land seized not wrought

iron by open arms

November 15, 2016

Spirit

by

Tochukwu Emmanuel Okafor

photo by Tammy Ruggles

I spend long hours talking with water in the bathroom every night. I tell Mama about this special bond I have with water. She laughs a hearty laugh and rolls her eyes. She tells me water does not speak. No ears, no mouth. “What is water if it is not human?” I ask her. She looks at me, finding it strange that I ask such a question.

She does not respond, instead, she asks me about school: Do I like my new class? Am I making new friends? When are my exams starting?

I no longer tell Mama about my nights with water. I don’t think of ever telling Papa. He won’t hear of such a thing in his house. Papa is a strict and hardworking man. He comes home by six in the evening and wakes up early before cockcrow. Most times I wonder if he ever sleeps. He speaks only when he is spoken to. The only time we talk is after he returns from work and has had his bath. He sits on the beige rug while we talk, a small, oval mirror in one hand and a shaving stick in the other. We talk a little. When he is not shaving, he is either watching CNN or reading the newspaper. I sit at the table in my room, studying. The whole house is dead silent until Mama returns from her shop. Mama assumes a daily routine in the kitchen. The clang of pots and the sweet smell of utazi soup fill the air around the house. When supper is served on the round glass table in the living room, we sit on the high-backed leather chairs and eat in silence. Only the clinks of spoons against ceramic plates break the quietude. After supper, Mama clears the table. I help her do the dishes. In a few hours’ time, Papa leads us in evening prayer. And after praying, he turns off the lights in the house. I pick my way to my room, avoiding the big flower vases and figurines lining the walls. Mama is in my room to say a short prayer and put a pocket-sized bible by my head and tell me good night.

In the dead of night, I do not sleep. I sneak like a thief into the bathroom. I lock the door behind me, and before gliding into the long bathtub, I pull off my nightgown. The smooth tiled walls of the bathtub are cold. I like the feel of anything cold on my bare skin, especially the feel of anything cold on my bare back. Water, too, is cold at this time of night. I squeeze the tap open and water starts pouring out. They are enchanting, these moments I steal away from my room to spend ample time with water. I wish for the night to go on without end, for the moon to tether itself to the clouds. I breathe in—wishes are what they are, mere wishes. In slow curves, I arch my back against the wall of the bathtub and shut my eyes. Water slips under the spaces beneath my relaxed form, rising at a slow speed, tickling me. I open my eyes when my body is under water. Only my head juts out. I turn off the tap, closing my eyes once more. I sleep when I am in the bathtub. In my sleep, I talk with water. Not the meaningful stringing of words into sentences. More like the silent mind conversation. I wake up when I feel the water has gone lukewarm. Or, perhaps, when I think I hear the tinkle of Papa’s alarm, filtering from his room. I release the plughole and do not wait for the water level in the bathtub to go down. Sometimes, I wait and watch the water drain through the small holes, in faint gurgles. Nobody knows about these nights I spend in the bathroom. Not even the early-rising Papa.

At school, I sleep through my classes. I put my head on the plastic table and sleep like a little child. A classmate will, sometimes, nudge me from behind to wake up. Still, after setting up a makeshift pillow with my books, all piled up to a comfortable height, I sleep. By way of punishment, a teacher tells me to stand for ten minutes. Most times, I stand for fifteen minutes. You are not to lean on anything, the teacher will instruct. But does this end my frequent bouts of sleep at school? Maybe.

Maybe not. One dry afternoon, in the heat of March, the school Principal summons my father to his office. I stand outside the Principal’s sunlit office overlooking the clean empty playground. The Principal walks in, Papa follows behind. Papa looks at me, his face expressionless, but turns away before I can get a chance to smile or wave at him. He is sweating, small shiny beads of wetness glittering on his forehead, like a sweaty glass of water. He must have been busy at his own office, I think, only to be distracted from work for my sake. I don’t want to feel guilty. No. Sleeping, after all, is not a punishable offence. Outside the locked door of the Principal’s office, I strain my ears to listen but hear nothing. Half an hour later, the Principal’s door flies open and I am standing beside Papa, mulling and mulling over in my mind the kind of explanation I will give for sleeping through my classes.

“You know why you’re here,” Papa says.

I nod, my face to the ground, my eyes, unblinking and glazed, searching for nothing in particular.

Turning to the Principal, Papa says, “It surprises me that she sleeps in class. At night, she turns in early.” He turns to me and asks, “What is the problem?”

“Papa, I—, I—,” I am almost choking. There is so much I wish to say. Maybe this is the right time to tell Papa. About water. About everything. But warm moist air and silence are all that escape my mouth.

“Sir, I do not wish to take any more of your time,” the Principal says, “I know you’re a very busy man. But please, it’s important she pay full attention in class. Her senior certificate exams are fast approaching.”

“Thank you, Mr. Principal.”

“Thank you, Sir.”

They shake hands. I watch Papa head back to his car and drive out of the school compound. The Principal leads me to my class. I walk to my seat, head hanging low, tongue feeling papery. In class, I overhear half-whispers from mates: Does she study all through the night? Is she nocturnal? Is she a witch, for I hear witches do not sleep at night? I fight sleep for the rest of school hours. At home, Papa never mentions a word about what had transpired at school. He checks on me from time to time as I study in my room. Mama returns from her shop quite early. The only thing she tells me is that my hair needs new braids. After supper, I lie on my bed and long for night to come.

At night, I do not go to the bathroom because I hear heavy footfalls outside my room. And a voice, too. The voice sounds gentle, filled with emotion, but firm. Is that Papa? I think, half listening, half worrying. I lever myself out of bed and tiptoe till I reach my bedroom door. The voice comes to me, clear, distinct. Mama’s voice. She is praying. I cannot make out what she is saying. Besides, she is clapping and singing at the same time. I crouch near the door in the dark. Like a folded leaf. The place I want to be is in the bathtub, under water, the only world where I feel weightless, listening to the ripples of the water, listening to water speak. In a few minutes, Mama stops praying, and singing, and clapping. I hear her calling my name. I don’t know why, but she is chanting my name at the top of her voice. I scramble off to bed without making the slightest sound. On my bed, I try to listen. My eyes peer into blank darkness. My bedroom door creaks open. A shaft of white light floods in, and on the vinyl tiled floor is Mama’s ghostly shadow. She walks round my room sprinkling something I think to be holy water. After this, she slips out and clicks the door shut behind her, closing out the only illumination, too. I struggle to sleep. At last, when sleep comes, I find myself wide awake in a pitch-dark room. My head is burning. I hear her voice again, her piercing voice, as if she’s in my head. She is screaming my name.

Ngene.

Ngene.

Ngene.

Mama’s midnight prayers go on for a week. Papa does not say anything about it. I dare not even talk about it. I am supposed to be sleeping. I have stopped sleeping at school. The school Principal and teachers are happy about this. But there is common gossip at school that I have been delivered of evil spirits. I don’t care what everybody at school is saying. I suffer only from the deep longing to be under water again.

One breezy Sunday night, I listen for Mama to begin her prayers. I lie in bed, waiting. No sound of her. Only the violent blows of wind against the windows. I spend the whole night waiting. And the next night. And the next two nights. It does not surprise me that she stops saying those midnight prayers. Who stays up all night brewing prayers like wine, only to awake early next morning, expecting to cheat Mother Nature at her workplace during the course of day? Three nights after she stops her midnight prayers, I step out of my room. My craving for water erupts like flames within me, its glowing bursts so strong that I feel the small muscles of my body contract and relax in unbounded joy. Hastening, I pull off my nightgown and slide into the bathtub. I turn on the tap and let the water rise to the brim. I feel my spirit soar and meld with water, an inexplicable joy searing my insides. I stay under water for a long while. I bring my head out only when my lungs need air. This blissful moment should last forever, I tell myself. Water wets my hair, loosening it into long flowing locks. Mama stands in the doorway, all the while she is gazing at me, a grave look filling her eyes. She is aghast at the sight of my motions in the bathtub. When I turn to stare at her, at her whole frame shaking with sobs, all the excitement and energy drains out of me.

“Ngene!” She hides her face in her hands.

I slip out of the bathtub into my nightgown, my whole body shaking with the fear of what may happen next. Papa is standing beside Mama in the doorway in no time. He fixes me with a long, burrowing look, shrugging, his lips twitching, as if a terrible thing has happened. I want to tell them that I enjoy being under water. I want to tell Mama to listen: She, too, can hear water speak.

“Papa Ngene,” Mama says, “What are we going to do?”

The whole drama that follows puzzles me. They are not looking at me, the guilty child playing in water in the middle of the night. They hold on to each other like magnets, Papa consoling Mama, both of them speaking in hushed tones.

“She is possessed by mmuo mmiri. Water spirit,” Papa says, “But she can be healed.”

“Why me? Why my only daughter?” Tears stream down Mama’s cheeks. And as they fall, I feel my heart fall, too, breaking into tiny shards.

Five o’clock and we are leaving Lagos. We drive through empty streets. The houses and kiosks and trees that line the streets stand like shadowy scenes on centre stage, under the dark blue clouds. We stop at police checkpoints and Mama ruffles her driving documents out of the glove compartment. We bump along potholed streets, open bags falling, their contents spilling. The cool air in the car is heavy with intense silence.

The sun rises by the time we are out of Lagos. The sky is a bright orange-yellow. Roads spring to life. Streets begin to fill. Loud music blares away in the distance. Mama rolls down her window and buys boiled groundnuts. She asks me if I want some. I tell her no. I don’t feel like eating anything, I say. She brings out her sequinned scarf from her handbag and covers her hair. She says, “Let us pray.” I am reclining in the back seat. My eyes are heavy. Mama’s eyes should be heavy, too.

After all, none of us has slept since last night. But her eyes are well trained on the road, something determined yet void of opinion about them. I wonder how she will pray and, at the same time, focus on her driving.

She begins to sing. I join her in the chorus, but absently. I am thinking of where we are travelling to. It is overhearing Papa, who is not with us in the car, mention Port-Harcourt in his conversation with Mama earlier this morning that gives me a hint of our destination. Are we going to visit a relative at Port-Harcourt? Is it at Port-Harcourt that Mama hopes to find the solution to this water spirit I am supposed to be possessed by? I look up at Mama. She tilts her head this way and that, somewhat in tune with each song. I look out through the window, and vanishing in a quick dance of dissolution are people and trees and things. I don’t know when I sleep.

In my sleep, I am under water again. It is calm. I listen, aching for that familiar voice, but the water does not speak. This is not a good sign, I tell myself. I sink upwards, my wide-set eyes gazing through water’s sky blue. Water throbs with life and energy. I have learnt how to stay longer under water in my sleep. But today, its deafening quietness, its serenity, displeases me. Its life and energy elude me. I don’t even hear the sound of ripples, or of waves climbing and crashing high above, or of life from the outside world. I let my thoughts amplify to their fullest extent, yet, they do not merge with the water. I shut my eyes and begin to drown, headlong, arms outstretched. I am plunging deeper and deeper, surrounded by bubbles and the cold blue, when a warm hand rouses me. I let my eyes flutter open, dazzled by brilliant streaks of afternoon light pouring in through the window. Mama gazes at me. Is that pity I see in her eyes? She tells me we are an hour away. You should eat, she says. She pushes a wrapped bag in my face. I take the bag from her, yawning, relieved with the sleep, but unhappy. I open the bag and eat in big scoops, a meal of jollof rice and fried plantain. After eating, I sleep. This time, there is no water. No ripples. No waves. No drowning.

The loud noise outside wakes me with a start. I rub my eyes with the base of my palm and look outside. I see a packed crowd of men and women and children, twirling and shivering and rolling on the ground. I am confused, so I ask Mama, “Where are we?” No reply. She removes her shoes and tells me to remove mine. She brings out a big leathery bible from her bag and passes me a bible almost as big as hers. She also brings out bottles of holy oil and holy water and tells me to get out of the car. The sun is setting, the sky is still. The cool breeze brushes past my ears, ruffling my pleated skirt. I follow Mama as she navigates through the people pressing us from all sides. I try to listen to what they are saying, but from the sea of sweaty faces and sudden mountainous roars here and there, I can make out nothing. From every angle, their Amens pummel my ears. The ground is cold and damp and wet gritty sands slap onto my feet, my toes smarting from small stones underneath. I look ahead, and sitting there is a measureless body of water. A river. I stop and watch the tranquil undulations of the river, where the reflection of the sun is set like liquid gold. I see boats floating along the surface. And there are children, too. They swim

close to the shore, their small hands paddling and flailing about in shallow water, propelling them back and forth. Birds revolve high in the air, in blind circles, cooing away. Mama shouts my name. A thick hand jolts me out of my distraction. I begin racing towards Mama.

A man dressed in white cassock and red beret approaches us. Mama goes on her knees and beckons me to do the same. The man’s eyes sink deep. He laughs, a short wooden laugh. He mutters words under his breath, his lips pursing between short intervals as he shudders. Whitish foams of spittle ooze from the sides of his mouth. His body shakes in a random frenzy. He has a stocky build and towering height, so that when he stands in front of Mama and me, we are kneeling right under his shadow.

“Woman, is this your daughter?” he says, his voice booming like lightening and fading away into space like vapour.

“Yes, Holy One,” Mama says. Her palms are pressed together, rubbing heat into each other.

Two men and a woman, dressed in the same manner as Holy One, walk towards us. They bear unlit red and white candles, the candles pocked by sand. They are singing in a language I do not understand.

“Arise, my daughter,” Holy One says to me, and to Mama, he says,

“What is wrong with her?”

“My husband and I think she is possessed by a water spirit,” Mama says.

Mama goes on to tell Holy One about what had happened last night in the bathroom. She is very dramatic about it. She even tells Holy One about my sleeping at school. Papa must have told her. Later, I will wonder why she never confronted me about it. Meanwhile, Holy One is staggering, shaking and nodding his bald head, as if possessed by another kind of spirit. The other three that surround him are still singing, their eyes skyward. I don’t know why, but Holy One clutches his bible against his chest and begins to chant: “Holy! Holy! Jah! Jah-Jehovah!” Then someone in the crowd rings a bell, and I am lost. I look at Mama where she kneels. She is crying. Her eyes are closed, her eyelids quivering. Her whole body is shivering. There is nothing wrong with me, I want to yell at her. How could she bring me here, this terrifying place, without my consent? She is praying now, aloud.

Evening falls on us.

“Come, my daughter,” Holy One says, gesturing over his broad shoulder. “Come.”

Holy One leads me. His three followers are right behind us. The children by the shore have long disappeared. I stop, a few paces from the river. I refuse to move any further. I turn and begin to make towards Mama. She has to take me home. But one of Holy One’s followers grabs me. The woman pulls my arms and binds them behind me. My eyes dilate in fear. I fight back, pushing forward, kicking, cursing. One of the men grasps my legs, pinning them to the ground as I fall. My head is burning again. Like in the dream. Except that I fear I won’t survive this time. The sensations of wind seem to cut into me like a sharp knife.

Holy One begins to pray:

Binding and casting, uprooting and destroying, the evil machinations of the water spirit. He slobbers and dances, dipping, whirling like a sandstorm. The woman, whose weight now presses upon me, warns me to close my eyes. And there, close to the river bank, they fall upon me with oil and water.

Author Bio:

Tochukwu Emmanuel Okafor is a Nigerian writer whose work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Open Road Review, Volume 1 Brooklyn, No Tokens, Warscapes, Litro, Flash Fiction Online, Bakwa Magazine, and elsewhere. He is an alumnus of Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA)/ Yusuf Ali Creative Writing Workshop (2015). An MTN and Etisalat scholar, he won the Comptroller Charles Edike Prize for Outstanding Essays (2014), the 37th Festus Iyayi Award for Excellence for Best Prose (2015), and was longlisted for the AMAB-HBF Flash Fiction Prize (2015). He is at work on a full-length debut novel.

November 3, 2016

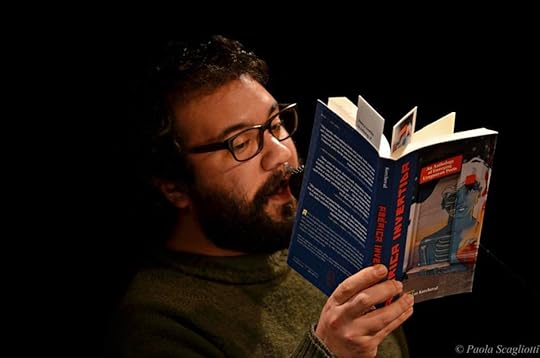

Jesse Lee Kercheval, the Ambassador of Uruguayan Poetry

Jesse Lee Kercheval

El Hoski

Audience

Andrea Durlacher

America Invertida

interview by Chip Livingston

photos by Paola Scagliotti

Jesse Lee Kercheval, renowned author, professor, editor, and translator, has joined with the University of New Mexico Press to present in English, for the first time, a collection of 22 Uruguayan poets under the age of 40. Kercheval paired poets and translators to produce a diverse collection of voices and styles in the magnificent anthology América Invertida.

The extraordinary Kercheval, whom I privately call the Embajadora de Poesía Uruguaya, agreed to take a few moments to answer my questions about how she ended up in Uruguay, how she came to translating these emerging and classic poets, and why she works so tirelessly to introduce them to English readers.

Chip Livingston: You were in Uruguay twice this year to participate in both the Mundial Poético de Montevideo I and to launch the bilingual anthology of emerging Uruguayan poets, América invertida, but before these professional literary events and the friendships you’ve developed there were established, what initially drew you to Uruguay and what was it or is it about the country that enchants you?

Jesse Lee Kerchevel: I ended up in Uruguay completely by chance. I grew up in Florida and my best friend’s mother was Cuban, but I never took a Spanish class. Since I was born in France, I always took French in high school and college. Then in 2008, my family and I went to Guanajuato, Mexico for two weeks over New Year’s to stay with a local family and attend a language school. This was really for my daughter, Magdalena, who was in high school, had always loved Spanish and had gone to a Spanish language immersion summer camp every year. My son, Max, was in the kids class. My husband, Dan, who had had Spanish growing up in Florida, in an intermediate class. I was in the class for people learning their numbers and colors. I did not get a verb until the end of my first week (gustar).

Let me tell you, it is really hard to have conversations at the dinner table without verbs. But I loved it. It was wonderful being a student again after so many years of being a professor. And I realized how foolish it felt living in America and not knowing Spanish. I am a big music fan—all kinds of music—and I knew I would often miss the announcements for concerts by say, Los Tigres del Norte, because it would only be publicized on Spanish language radio stations. I had a sabbatical year coming up and I decided I would spend it studying Spanish. The question was where. I thought about Chile or maybe Argentina, then a friend in the Spanish Department suggested Montevideo. My husband and my son would be coming with me, and my friend said she thought it would be a good place for Max to be in school.

I couldn’t imagine committing to a year in a country without visiting it so we went to Uruguay for two weeks over Christmas. The minute we arrived, Max knew he had found his country. There are not many 12-year-old foreigners in Montevideo and when he walked down he street, he was an Uruguayo. Montevideo reminded me of Italy—with good reason since about a quarter of the population are descended from Italian immigrants. But I was startled by the Spanish, all the zzzhs in place of soft Y sounds for the double LLs and Ys. But I went to hear a concert by the murga group Falta y Resto in the gorgeous old opera house Teatro Solis. Murgas are a cappella groups that sing satirical and political songs and are part of the great Uruguayan carnival tradition. We also saw comparsas, companies of candombe drummers, playing in the streets, getting ready for Carnival. We went to a Daniel Viglietti concert. Viglietti often is called the Bob Dylan of Uruguay, but I think the Pete Seeger of Uruguay might be a better comparison. It was the last concert of the year, before everything closed for summer vacation, and the theater was packed with Uruguayan families, everyone singing along. So it was the music that first drew me to Uruguay. My husband, on the other hand, noticed how expensive it was to live there. Uruguayans struggle with the high cost of housing and for us it was more expensive than Madison (Wisconsin). But Max was the one involuntarily leaving his friends for a year to go to school in a language he didn’t speak—so Uruguay it was.

So we moved to Montevideo—son, husband, even our then ten-year-old rat terrier—for nine months. I started taking Spanish language classes five to eight hours a day. My son started seventh grade, the first year of high school in Uruguay at Liceo Latinamericano where he was their first foreign student. At first, I remember standing in a bookstore and thinking how crazy this was for a writer—to move to a country where I couldn’t read a any of the books for sale around me. But soon that was not true. When I had told friends and colleagues about my plans for a sabbatical year studying Spanish, everyone had assumed since I was a poet, I was planning on translating poetry. But I had told them all I only wanted to have conversations about tomatoes. And that was true for the first months. All my first friends, still my friends, from those days are people completely outside the world of professors and poets. One of my best friends was Max’s first Spanish teacher (and her husband, it turned out, plays in Daniel Viglietti’s band). But little by little, I drifted back to my old ways. One day, standing in the same bookstore, I bought my first book of Uruguayan poetry, the complete poems of Idea Vilariño—and after that, there was no going back.

I should also add I am a big fútbol fan so that was another early, strong bond with Uruguay, a country that produces two things in astonishing abundance—poets and world class soccer players.

Jesse Lee Kercheval

CL: Did your translation work begin with Vilariño and the poets who were part of the Generacion del 45? And what led you to the work of the younger, emerging poets included in América invertida and Earth, Sky and Water?

JLK: My first translation project was América invertida: An Anthology of Emerging Uruguayan Poets. The idea was to put to gather a bilingual anthology of Uruguayan poets under 40 by matching each poet with a poet who was also a translator in the U.S. I wanted to do something for the young poets I had heard reading in Montevideo, where there is a reading, sometimes two or three, most nights—some part of long running series like the Ronda de poetas, run by the poet Martín Barea Mattos, who is in the anthology, or La Pluma Azul, one of the organizers of that series, Alicia Preza, is in the anthology as well and others that come and go or get reborn after an absence, many centered on the boliche—bar or pub—Kalima.

The anthology was just published by the University of New Mexico Press in September. I was in Uruguay for a book presentation reading and have been doing readings myself or with translators and poets around the country all Autumn. This anthology has become more than a book—I really do think of it as a project. So far five books have been or will be published that were a direct result of the pairing of Uruguayan and American poets and the anthology and more are in the works.

But while I was working on the anthology, I fell in love with the poetry of Circe Maia, who, at 84, is one of the greatest living Uruguayan poets, This resulted The Invisible Bridge/ El puente invisible: Selected Poems of Circe Maia, which was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press last Fall. Then I translated a book by one of the poets from América invertida, Javier Etchevarren. That book, Fable of an Inconsolable Man, will be published by Action Books in February and I am bringing Javier to the U.S. for a tour. He will be at the Associated Writing Programs convention in Washington, D.C., at my university, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Notre Dame, the home of Action Books, and at McNally Jackson Books in New York.

I am also bringing Virginia Lucas, another wonderful Uruguayan poet to the U.S. on that tour. She is in a second anthology I edited, Earth, Sky and Water: A Bilingual Anthology of Environmental Poetry. This book, which included poems by Uruguayan and Argentinian poets, was published in Uruguay by the publisher Yaugarú and the South American Institute for Resilience and Sustainability Studies (SARAS). SARAS is a wonderful international scientific institute that is based in Uruguay and they contacted me about bringing poets to their annual conference. I thought it was a wonderful idea! There is not enough collaboration between the arts and the sciences. I issued a call for poems by Uruguayan and Argentinian poets on environmental themes, SARAS awarded prizes to three of the poets, and I arranged for ten to be translated and they were published in the bilingual anthology. The three prize winners, Natalie Romero (Argentina, translated by Seth Michelson), Sebastián Rivero (Uruguay, translated by Catherine Jagoe) and Virginia Lucas (Uruguay, translated by Jen Hofer) read at the conference. That was a wonderful day with so much poetry being shared with hundreds of scientists. In February, Dialogos Books is bringing the anthology out in the U.S. and SARAS is paying for Virginia Lucas’s trip to the U.S.

Then I finally started translating Idea Vilariño—so she is actually my most recent project of all these!

CL: You mention in the Introduction to AMÉRICA INVERTIDA how pervasive poetry and writing are in Uruguayan society, quoting Leo Maslíah’s song “Biromes y servilletas” (“Bic Pens and Napkins”) and adding that he isn’t exaggerating in his lines about Montevideo, as the place where “there are poets, poets, poets” who only “write, write, write” on every piece of paper they can find. And Uruguayans seem to place such high esteem on poets. I remember how surprised I was to find the monument with Juana de Ibarbourou’s poem along the Rambla in Pocitos, not to mention her portrait on the U$Y1,000 peso note. Why do you think Uruguayans pay such high regard for their writers?

JKL: I don’t want to exaggerate—poetry readings do not take place in packed stadiums in Uruguay (unlike soccer games). But I do think it is part of the Uruguayan national identity. All countries have stories/histories that help them define their sense of who they are. For Uruguay, poetry is part of this. Mario Benedetti, part of the famous Generation of ’45 and part of the generation of writers, like Borges, who brought Latin American writing to the attention of U.S. readers, wrote in a cafe in the downtown (centro) of Montevideo. He died in 2009 but there is still a moving tribute to him in the window of the cafe.

CL: English readers in the U.S. have long had access to translations of some popular South American writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa, Isabelle Allende and Pablo Neruda. What drives you to work so hard to make other, less known Latino authors, accessible to more readers?

JKL: Well, I think by not having access to the writers of Uruguay in translation, English readers are missing some of the best of the best—and though I may not be impartial, it is true that the poetry of Uruguay is widely acknowledged in Latin America as important. People I meet from other countries in Latin America are often shocked to hear how few of the Uruguayan greats—Idea Vilariño, Ida Vitale, Mario Benedetti, even prose writers like Juan Carlos Onetti or Horacio Quiroga—are available in complete or good translations in English.

My current obsession is the women poets of Uruguay. Uruguay really has an unbroken line of amazing, world class women poets and they need to be known outside Uruguay and outside Spanish. It frustrates me to see recent anthologies of Latin or South American poetry with so few women in them—when there are such great women poets in Uruguay alone. So, I am working hard to get them translated or, if they are translated, better known. I’ve done a recent feature for Drunken Boat of Uruguayan women poets and I working on one for the Western Humanities Review.

CL: You teach creative writing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison so you are obviously familiar with working with emerging writers. Do you see a distinction in the emerging voices between the two hemispheres, either in subject matter, form, or style?

JKL: The surprising thing, really, is the similarity. In form and style, the range in América Invertida runs from traditional—sonnets—to experimental to spoken word. In subject matter, there are also a lot of similarities, women writing about what it is like to be a woman in the world, poets writing about their childhoods, but the political and historical subject matter are different—and that difference is one of the things that makes the poems so interesting and so rich.

CL: How is translating the younger poets different from translating the more classic poet of South America?

JLK: The poet I translated for the anthology América invertida, Agustín Lucas, who is a both professional fútbol player AND a poet, uses a lot of lunfardo, the tango slang of Uruguay and Argentina, which is constantly being updated with new meanings, and lots of references to a card game, trucho, which is well known there but unknown here. One of my jobs as editor was to go over all the translators work and make sure they were not making a mistake with an Uruguayan reference or word. Basically, Uruguay has a different word for every fruit, vegetable and item of clothing—and that is before you get to the lunfardo.

But overall, the Uruguayans are very concerned about the environment, so that has made its way into the poetry. Some writers are also concerned with their country’s history, especially the treatment of the indigenous people during the settlement of Uruguay, as well as with social injustice and what they see as a growing problem of inequality. Many of the woman poets address the issue of what it is like to be a woman in Uruguay.

CL: You were in Montevideo in September to launch the América invertida anthology with a series of readings. Can you talk a little about the book’s reception there?

JKL: The reading in Montevideo for América invertida was a real celebration! It was in the lovely auditorium of the Spanish Cultural Center in the Ciudad Vieja. Nearly all the poets read and then there was wine! A culmination of a big project and a lot of work and it was so good to hear everyone’s voices! I was also on Radio Uruguay with two of the poets, Karen Wild and Javier Etchevarren, talking about the anthology. Everyone there—poets, public—and here—translators, the UNM Press—are delighted with how it turned out!

CL: You mentioned how successful the placement was for the poems comprising América invertida, that nearly all of the translations and poems were first published in literary journals. Is that excitement toward the South American poets continuing?

JLK: I hoped this pairing would produce work beyond the anthology and open up more doors for the Uruguayan poets, and it succeeded belong my wildest dreams. Not only were nearly all the poems (and more) published in magazines, but ten or more of the translators went on to translate whole collections by their poets. Six of those are out or forthcoming.

CL: That’s fantastic. And also the Earth, Sky and Water anthology. Can you tell us more about that series and this anthology, the first one to come out in the U.S.?

JLK: The Earth, Sky, and Water anthology was a collaboration with an international scientific organization SARAS, which hold a conference every year in Maldonado, Uruguay. For this year’s conference, they contacted me saying they wanted to work with poets, and so I put out a call for poems from Argentine and Uruguayan poets about the environment and environmental issues. The Uruguayan poet Marcelo Pelligrini picked three prize winners and seven other poets to include in the anthology. Then, as with América invertida, I paired each a poet with a poet who was also a translator. The Uruguayan publisher, Yagaurú, designed and printed the anthology, which was distributed at the conference. There was a wonderful reading at the conference, which left me wishing more scientific conferences had a vision that included the arts. But more broadly, made me realize that all our closed worlds—conferences for writers, translators, historians, economists, engineers—would benefit if we opened our doors to others and their different but complementary visions of the future. Then we had another reading in Montevideo.

I expected that to be the end of that project. But then, when I was in Montevideo for the Mundial Poético in May, Bill Lavender, one of the U.S. poets participating in the conference, who is also the editor and publisher of Lavender Ink/ Diálogos Books, bought a copy of the anthology and said he wanted to bring it out in the United States. Poetry can be a small and wonderful world! The anthology will be out in time for the Associated Writers and Writing Programs annual conference in Washington, D.C. in early February 2017. I am working right now to get some money together to bring a few of the poets from América invertida and from Earth, Sky and Water to the U.S. for the conference and a tour of other cities. Fingers crossed about that!

Here is a poem from América Invertida by Laura Chalar, translation by Erica Mena. The original Spanish is below.

avenida 18 de julio

if walt whitman were here, how he would sing of them and sing

to them with the deep voice of a street prophet, dedicating the

hymn of his long grey vigil to the dark flock of the gentle poor,

ant citizens, his hand touching the woman who waits at the bus

stop, the policeman, the scavenger, the law clerk in his exhausted

shoes, the begging children, the begging elderly, the fat salesgirls,

the kids spilling out of the law school, the garrapiñero, the watch-

band seller, the half-blind lottery ticket seller, the supreme court

judge who is running late again, the man who just bought a smart-

phone, the woman who recites poems on the bus, the shoe shiner,

the people handing out flyers for loan sharks or massage parlors,

and me, who watches it all with the love of someone who is bound

to leave, someone who is already leaving.

por dieciocho

si estuviera walt whitman acá, cómo los cantaría y les cantaría

con su ronca voz de augur callejero, dedicándole su himno de

larga vigilia gris a la oscura grey de pobres mansos, ciudadanía

de hormigas, tocando con su mano a la que espera en la parada,

al policía, al hurgador, al procurador cansado en sus zapatos, a

los niños que piden, a los viejos que piden, a las gordas de la

expo, a los chiquilines que salen de facultad, al garrapiñero, al del

puestito de correas de reloj, al quinielero medio ciego, al ministro

de la suprema corte que una vez más llega tarde, al que se com-

pró el celular con internet, a la que recita poemas en el ómnibus,

al lustrabotas, a las que reparten volantes de usureros o casas de

masajes y a mí, que miro todo con el amor de quien se va, quien

se está yendo.