Walker Elliott Rowe's Blog, page 3

June 15, 2017

Santiago Metro to Add Yet another New Line to Reduce Congestion

by

McKenzie Ingram

Santiago, Chile. 14 June 2017

The plan that thousands of Santiagüinos have hoped for and relied on is finally gaining ground.

Line 7, the much-needed remedy to decongest the main route of Santiago’s subway system, was finally declared on the first of June to have cemented its funding.

The line will run from an affluent community named Vitacura, along the main line of the metro that is currently congested near downtown, and end on the other side of Santiago in Renca. This line would not only lessen the burden of the primary line of the metro, but would also stretch to new parts of the city, reaching more than 1,300,000 people. This line has the ability to unite people from across the city by shortening a journey of 2 hours to less than 30 minutes and revitalizing nearby areas of low population density (El Mercurio).

The 45 kilometer-long 7th line would also put Chile in the top 20 most extensive metro lines in the world, among the likes of Shanghai, London, New York City, and Tokyo.

The plan was originally created in 2014 by current President Michelle Bachelet but will begin in 2020 and hopefully finish by 2025, barring budget deficits or other potential obstacles.

Why all the sudden hype about this far-off solution, then?

The current political race in Chile has certainly played a role in the buzz around this possibility.

Presidential candidate Sebastián Piñera promised to add three new lines to the metro through a seven-million-dollar project that would span over 10 years. This potential end to the seemingly continuous construction on the metro system has been stirring up excitement and expectation in communities across Santiago.

A growing host of problems surrounding the Santiago public transportation system make the construction a tantalizing prospect, including a 35% rate of evasion where users avoid paying, as well as an over-saturation of the main line, which currently is struggling under nearly double the density per square meter it was built to contain. Iván Poduje, an urban planner and academic from the Universidad Católica, warns that the stability of the whole metro system could be put in jeopardy if a solution is not soon reached (La Tercera).

Time is of the essence regarding this heavily-relied upon system of transport, and citizens of Santiago are certainly ready for ground to break on this construction toward a more efficient, less crowded future.

June 3, 2017

Latest Earthquakes in Chile Mag > 4.0 Real-time Feed

June 2, 2017

Suns Shining at Midnight: Three Poems by Tim Vivian

by Tim Vivian

Photo by Akın Saner

Suns Shining at Midnight: Three Poems

Excerpts from a Journal of

the Plague Years: 2016-2020

Emergency

April 1, 2017

Exsanguinated prose.

Inveterate lies. Now

we stand on tiptoes

to gated windows that

display deboned meat.

A passerby craves flesh;

hungry, she’s admiring

the storefront window:

chorizo; menudo here

sábados y domingos.

But no one in this our

administration will ever

confess that this meat

comes, desaparecido,

from those now hiding

illegal, indocumentados.

A child, her family doll

en su diminuta mano rota,

begins to cry. Our good

citizen has her phone

in her hand. As she dials

911, La Migra, and ICE,

she feels, unexpected,

wetness between her

legs. She stops. Hello?

the disembodied voice

requests. Is this moisture

hemorrhagic or orgasm?

Her phone drops. Hello?

What is your emergency?

*****

Beelzebub to His Son

Matthew 11:14-19

Whatever they say to you belongs

to me, but not vice-versa. That’s

just the way it is. Get over it.

But Dad, that’s not fair! No,

it isn’t, forever and ever. Amen.

As you pout now on each street

corner, remember what I said

a few centuries ago when you

were just a mite and my dear

friends had not yet invented

nuclear weapons. Ashes to ashes,

dust to chemical dust. All fall

down. The clowns of Auschwitz

celebrated Mass far superior

to any priest or pontiff. Even

cremated children laughed and

spat out the body and blood.

And here we are again. Aren’t

we always here again? Yes,

my son, my murderer. Do you

see that streetlight over there?

It’s powered not by flesh and

blood but by gristle, by each

indifference of each individual.

That light will shine even when

the grid implodes. No, it’s not

punishment but success. Every

thought you have must run

counterclockwise to what they

think here. Only then will you

understand that twenty below

zero is better than Hawai’i. Ah,

do you hear their petitions, each

articulated in language they

do not otherwise use? No? But

draw nearer. See the ovens in

my eyes, each Hiroshima and

Nagasaki, each frozen Gulag?

I was always at ground zero. I’ve

even claimed to press the button

when it needed pressing. But past

will never be prologue. You think

past is always prologue. But

don’t you see? Parliaments and

legislatures have nothing of what

you and I, and even God’s angels,

call memory. Memory for them

is a viper’s den, a game reserve

where servants of the rich hunt

animals to extinction. Only then

do monuments return to dust and

yesterday’s lies, spoken enough,

become truth. Truth—that’s the

carrot and the stick, my son, that

you will hold out to them. When

stick and carrot join, then you

can call each person’s Congress

into session. Point to the mess

on the floor, call in God’s janitors.

Only then will ambulances come

and, when the sirens no longer

breathe but die laughing, then,

and only then, advertise the truth

on TV and the internet. Capillaries

will then constrict, blood flow

will stop and each canary in

each mine will find freedom.

Watch the flags tailing behind.

When the sun atrophies them,

then you will have lost and won.

* * * * *

Epithalamion II

Count the scattered applause.

Now betoken each finger as

it lies at rest in the darkening

silence. Isn’t marriage just

like this? In the beginning

the applause, redundant,

sounds like the clapping in

those old black-and-white

reels where the captives sign

unanimity at a Communist

Party conference. Not one

of them demurs. Since now

there are few original first

nights, the audience of two,

even lying together naked,

has already begun to see

importance in reruns. When

the tenth episode concludes or

the series ends, as we know it

will, they have long looked to

what brought them here. Here

there can be suns shining at

midnight but, more often than

not, not. What would we, long

married, wonder, if in fact

hibernal solstice now shone

like summer? We would,

we hope, rip all our clothes

off and run into vernal surf

as though it were virgin and

pregnant. And so, now, we

wish them our very best as

agony, sorrow and, yes, regret

pitch their tents just as, long

ago, the Logos did in peasant

Galilee, at once smelling blood.

* * *

Pitch their tents: John 1:14, of the

Logos or Word. Eskḗnosen < skēnḗ,

tent; usually translated as “dwelled

among us.”

Tim Vivian has published numerous books, article, and book reviews in his academic field of study, early Christian monasticism. He has lately turned more attention to literary efforts, publishing articles on the poetry of Denise Levertov and Rowan Williams and on the novels of Marilynne Robinson. You may reach him at tvivian@csub.edu.

May 12, 2017

Guzzled

by

Jonathan B. Ferrini

thumbail artwork by Rene Castro

Imagine finding a diamond embedded in the ground. You pull it from the earth and although the diamond glistens, you’re repulsed by the insects scurrying around under it. Like those insects, the hotel, restaurant, and tourism workers toil unnoticed and unappreciated under the glistening neon lights of Las Vegas.

My father was the only child of Italian immigrants who traded the Chicago winters for the heat of the Vegas desert fifty years ago. He found work as a busboy at a swanky “old school” steak house adorned with red leather booths, dim lighting, and a thousand broken promises embedded within the dark mahogany walls. He rose to Maître’d and knew his global clientele by name. Pop married my mother who was a Vegas show girl. The grueling show schedules wreaked havoc on her voluptuous body and she sought relief from her addiction to prescription painkillers. It wasn’t long before mom lost her good looks and sexy figure, but she found work as a hotel concierge to “high rollers”. She was fond of taking her opiates with a chaser of gin. She died in bed suffocating on her own vomit. Pop loved thoroughbred horse racing and spent his free time placing bets at tracks throughout the nation at his favorite casino sports book. When I asked him why he kept betting after losing so much money, he answered that he liked “the action”.

Vegas is a town of transients seeking “do-over’s and make-over’s’. My name is Ronnie Ricci. I’m a rarity in Vegas because I was born and raised here. My parents worked hard to provide their only son with a good childhood but they were only able to rent the American dream living paycheck to paycheck. We lived in a spacious home fronting the seventh hole on a private golf club where I found work as a caddy. In my spare time, I practiced golf and became good enough to earn a golf scholarship to an Arizona college. I spent more time on the golf course than in the classroom. I made money hustling players but the players complained and the clubs blackballed me. Like Pop, I craved the “action” of hustling golf. I barely managed to graduate in five years with a degree in Business Administration and returned home to Vegas.

My reputation as a golf hustler preceded me so I couldn’t find work as a golf instructor or even a caddy in Vegas. I worked as a valet parking attendant late into the evenings and slept all day.

Valet parking is a grind but all the running involved to fetch cars for the guests keeps you in good physical shape. The fastest valets made the most money, parked more cars, and earned the most tips. Valet parking was a job but I yearned for a professional career.

My college grades were mediocre and I struggled to find a graduate or professional school which would accept me. My father was just proud of my graduation from law school and happy to have me living with him at home while I parked cars. The streets of Vegas are lined with billboards advertising “slip and fall” attorneys who make big money representing hotel, casino, and restaurant employees seeking worker compensation claims from their employers. I’d meet these big shot attorneys parking their exotic cars and their bespoke suits and Italian loafers impressed me.

One evening a black Ferrari approached the valet stand. I opened the passenger door for a beautiful, inebriated blond woman who vomited on me. I handled the situation with calm and focused upon safely placing the woman on a nearby bench and fetching her a towel and bottle of water. The male driver was embarrassed and so grateful for my kindness, he handed me a $100 tip. After changing clothes, I returned to the valet queue and parked cars late into the night. Hours later, the owner of the Ferrari returned to the valet stand and although another valet was in queue ahead of me, the man motioned for me to retrieve his car. I quickly returned with the Ferrari which was a thrill to drive. I recognized him from one of the billboard advertisements and I told him so as I opened the door for his girlfriend. I told him that I just graduated from college but my grades weren’t good enough for law school and asked for his advice. The lawyer said, “it’s not about the reputation of the law school you attend. Pass the bar exam and you’re a member of the club!” He revved the engine of his Ferrari, rolled down his window and said “learn to pass the bar!” He sped off onto the strip.

It was easy to find a non-accredited law school eager to take my tuition money with the promise me that I would be one of the lucky 40% of the graduating class to pass the Nevada Bar exam. I graduated, received my law degree, but failed to pass the bar exam after three attempts. It was a Saturday night on Labor Day weekend and the valet stand was SRO. I was so busy I couldn’t stop to relieve myself as I was making tip money hand over fist. Upon returning to the valet stand to deliver a sleek new Maserati to a high roller, I felt a tap on my shoulder from the Valet Parking Manager who told me to head for the Emergency Room at University Hospital. My father suffered a heart attack.

I arrived at the Cardiac ICU just in time to see my lifeless father wheeled from the treatment room. Electrodes and IV tubes dangled from the gurney and the green flat line of the cardiac monitor reminded me of a dying Vegas neon sign. I missed my mom but Pop’s passing hit me hard. He was an advocate of the “work hard and get ahead” mentality, never missing a day of work. The steakhouse Pop worked at for 30 years at the steakhouse didn’t even send a card of condolence. He left me nothing except a mortgage and several thousand dollars in the bank. I was told dinner reservations at the steak house fell off 30% after his passing.

Pop wanted to be cremated. He was in a cardboard casket and I kissed his cold forehead. He had a frozen grin, as if relieved to be released from the world. I watched the attendant carefully slide the cardboard casket into the furnace and close the door. He told me to come back in two hours. I watched the heat vapors waft up from the crematorium smokestack and towards heaven, hoping that Pop was on his way to a reunion with mom. I contemplated my father’s decades of devoted service to one employer, and it struck me how unfair it was that he had nothing to show for his work. I vowed to pass the bar exam and become a big shot Vegas lawyer. I returned to the crematorium in time to see my father’s charred bones carefully brushed from the furnace into a metal container. The contents of the container were poured into a cylinder which pulverized the bones into a fine powder and placed into a cardboard box with Pops name on it. I knew Pop wanted his ashes scattered at sea, and I insisted on doing it myself. I placed his remains on my nightstand as both a loving memory and inspiration. It was my goal to drive down Pacific Coast Highway in my own Ferrari one day with Pops remains in the passenger seat. I’d open a bottle of cognac and toast him before scattering his ashes into the Pacific Ocean.

As I left the crematory and entered the office to settle the bill, the Funeral Director pointed to an elaborate wreath on a stand reading “In Loving Memory” and said, “This just arrived for you, Mr. Ricci”. The card had an embossed “SH” on the envelope which I opened. A handwritten note read:

“I was a friend of your father for 30 years. He loved you and spoke often about his son the golf pro and future lawyer. He will be missed by Vegas.

Regards, Sy Hersh”

The note included Sy’s business card: “Sy Hersh. President. Zion Taxi Cooperative”. On the back of the card he wrote, “I have a proposition for you. Please contact me at your convenience.”

The taxi cab industry in Vegas is a big business and I knew the President of Zion Taxi Cooperative was a powerful man with influential contacts. My valet salary and tips didn’t cover the mortgage payments but I wouldn’t allow Pop’s dream home to fall into foreclosure. Sy’s proposition was timely. I dialed Sy’s number and the secretary made an appointment for me to meet Mr. Hersh.

Just a couple of blocks east of the glitzy Vegas strip is mangy Las Vegas. The streets are lined with tattoo parlors, auto body shops, pawn shops, gun shops, and massage parlors. Homeless people roam about. This neighborhood was also the headquarters of the Zion Taxi Cab Cooperative. I approached a large yard smelling of gasoline and radiator fluid. It was full of hundreds of taxi cabs. The property was fenced with high razor wire and warning signs to “Keep Out. Guard Dogs on Duty”. I parked on the street and walked in. Ahead of me was a two story windowless building which resembled a bunker. Atop the building was a flag pole proudly flying both the American and Israeli flags. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed that I was being tracked by a tall, muscular and menacing black man. The yard was teeming with activity and resembled the UN General Assembly sans the suits and ties. There were drivers mulling about– smoking, and speaking every language on the face of the earth. Mechanics were busy repairing taxis, and impatient drivers waited in line to check in or check out a taxi.

As I reached the front door, a sleeping pit bull woke up and growled. I entered a hot dingy office cordoned off with a counter. An old ceiling fan turned slowly and squeaked accompanied by a radio with a broken speaker sputtering big band music. All the office furniture was old and beat up. An elderly lady with a bad wig and cigarette dangling out of the corner of her mouth was using the two finger method of typing on a vintage manual typewriter with carbon paper. On the wall behind her were framed photos of Theodore Herzl, David Ben-Gurion, and Golda Meir. I heard phones ringing and a taxi dispatcher in another room shouting into a two way radio. She didn’t notice I had entered until I tapped the bell on the counter.

She rose and approached me saying, “You must be Mr. Ricci. Mr. Hersh is expecting you”. She reached for the handset of a black rotary dial telephone and said into it “Mr. Hersh, your appointment is here sir.” She hung up the phone, pushed a buzzer, and the door in the counter opened. Her accent was native New Yorker and asked “Would you like a coffee?” I spotted the jar of freeze dried coffee and a dirty coffee pot and politely declined. The woman returned to the typewriter, saying, “Mr. Hersh is in the office at the end of the hall. Knock before entering.”

I approached a door reading “Sy Hersh, President.” I heard a heated meeting in an adjoiningvconference room. I knocked on the door and a voice inside the office shouted, “Enter!”Cigarette smoke filled the room and made it uncomfortable for me to breathe. Sy was an imposing man in his seventies, balding, overweight, and juggling a phone in each hand. His conversations were interrupted by a chronic smoker’s cough. Sy’s hands were large like bear paws and showed the callouses of a man who worked hard for a living.. His old desk was stacked with paper, two phones, and table lamp. There was no computer. He pointed to a wooden chair in front of his desk and motioned for me to sit. I could judge from the phone conversations Sy had a firm grip on his company’s finances and an amazing ability for computing numbers accurately on the spot. I recognized fine clothing working as a valet and concluded Sy’s double-breasted gray suit was Armani worn over a black t-shirt. As Sy was finishing his calls, I scanned the walls of his office which were adorned with framed photos of Sy as a young Israeli soldier, his father and mother, and Sy with all the casino moguls.

Sy hung up the phone, immediately grabbed a pack of cigarettes from the desk drawer, reached into his Armani suit for a gold cigarette lighter, lit a cigarette, and took a long deep drag while reaching to shake my hand with a vice-like grip. Sy was not the type of man I wanted to be faced against in a negotiation or a fight. Sy stared deep into my eyes like a shark about to devour its prey and said sympathetically, “I’m sorry for your loss, kid. They’re not making fellas like your father anymore.” I thanked him to which he replied, “Call me Sy, Ronnie. Your father told me about your legal training and your golf hustle and these are the talents I need, Ronnie. Those calls I was taking were with my accountant and investment advisor. My insurance premiums are eating me alive. The taxi business is plagued with bogus insurance claims by shyster sharks representing passengers and taxi drivers seeking a quick buck. I need a settlement man”. I asked what he meant by “settlement man.” “I understand you’ve taken the Nevada bar exam three times which makes you as good as any shyster in Vegas. You’re also a single guy who wants to get out of the valet gig, correct?”

“That’s correct, Sy”, I replied.

“I’ll hire you to respond to any accident involving one of my cabs and your job will be to obtain an unconditional release from the passengers and the driver.”

“Why would they want to sign a release?” I asked.

Sy rose from behind his desk, and I could see that he was wearing Gucci loafers without socks. Sy opened a nearby closet door revealing a walk-in safe. He retrieved a silver metal briefcase and laid it on his desk. He dialed the four-digit combination, opened the case which was filled to the brim with stacks of $100 bills. “They’ll sign because you’ll pay them cash on the spot to do so. It’s a 24/7 job and you’ll live in the studio apartment upstairs rent free. Some days you’ll have no work and other days you work around the clock. This taxi yard is strategically positioned within the center of Vegas and it’s less than a 10-minute drive to any accident in the city. Your pay is $500 per day, cash, and we can talk about a bonus later. Are you in or out?” Sy stared at me expecting a quick answer and I knew that any hesitation would end the meeting immediately and I’d be back parking cars that evening. I thought about Pop’s house facing what he fondly referred to as the lucky “seventh” hole I could rent it out since I’d be staying upstairs in the studio rent free, and Sy’s pay would cover the taxes and insurance.

I rose, extended my hand and said, “I accept, Sy.”

“Splendid”, he replied, closing the briefcase. “Follow me. I want to introduce you to my gang.”

The term “guzzled” describes a radio call assigned to a taxi driver who speeds to the pickup destination only to find another taxi intercepted the radio dispatch, arrived earlier, and stole the fare. To be “guzzled” is to be hustled. My meeting with Sy Hersh and the “gang” would change my life forever!

I followed Sy down the hall and into a conference room. The menacing black man was there along with a uniformed police captain, and a sixty-something guy dressed in a wrinkled drip-and– dry suit with wide seventies style lapels. Sy introduced the captain, Jonny Sample who headed up the traffic division and responsible for all accident investigations within the city. Jonny reported directly to the chief of police and had power within the department. I was struck by his movie star good looks. Jonny was fifty-something, tall, athletic, had a thick mane of sandy blond hair, deep blue eyes, and a savoir faire uncommon with cops. I’d come to learn that he was a child television star which explained his charm and disarming personality.

Sy next introduced me to the man in the bad suit. Steward “Stuey” Standard who was Sy’s insurance salesman. Stuey extended his sweaty palm to shake my hand and gave me his business card reading “Standard Independent Insurance Agency.” “Happy to know you, call me Hush.” Stuey was in his sixties but looked ten years older because of the blush on his cheeks and bloated stomach. He had the faint smell of booze on his breath.

Sy turned to an old frail man with his silver hair parted down the middle wearing a white Physician’s coat, and “Doc” Rigger managed a subtle wave to the group. Doc was a former Chief Medical Examiner of a major city but gambling led to a career downfall. He found a second chance moving to Vegas where he worked as the doctor at the state prison. Sy helped him obtain a clinical professorship at the local medical school, which needed an expert in “evasive” toxicology techniques who could prescribe drug enhancements to the school’s athletes. Now Doc had contacts throughout Hollywood and the ME’s offices. We called Doc the “Obituary Oracle” because he could predict to the day the death of any ailing celebrity he was tracking.

The last man Sy introduced was the menacing black man who sat silent and motionless. His name was Nassir and Sy said he would be my “trainer”. Sy proclaimed “This is my team, Ronnie. Jonny’s traffic cops write the accident reports favorable to Zion as does Doc. Stuey schmooze’s the insurance carriers when we’re hit with claims. Nassir is my right-hand man and bone crusher.”

Nassir was 6’4”, 250 pounds of lean chiseled muscle. He kept his head shaved and wore one ruby crucifix earring. Sy called him “Black Mr. Clean”. Sy was the only one who dared call Nassir by anything but his birth name. When asked why he chose a ruby earring instead of gold or silver, he would mutter “It reminds me of the blood I’ve spilled and will spill from me when the Lord calls.”

Nassir washed out of the NFL, couldn’t catch a break as a heavyweight boxer, and failed as a thief when he and his gang held up a drug dealer who was killed in the melee. Nassir wasn’t the trigger man but was charged with murder one as an accomplice. Nassir spent one year in county jail awaiting his trial which resulted in an 11-1 hung jury. Nassir caught a break, found religion, and like so many others seeking a new start, moved to Vegas. He turned his life around as a bouncer at strip clubs and eventually found a coveted undercover security job at one of the classiest casinos in Vegas frequented by Sy. The two have been friends, employer and employee ever since. Sy always supports the underdog.

My first week on the job was grueling. I lived in the second-floor efficiency apartment and was on call 24/7. Some days I would have no calls and others required working around the clock. Nassir was assigned to teach me the ropes but Nassir’s teaching style was to throw me to the wolves so I would learn the hard way. We arrived at accident scenes in a former Vegas police undercover car with spotlights mounted at the windshield and the two-way radio antennas still attached. This gave us an aura of authority and negotiating leverage for Zion. Nassir told me that alcohol was our best friend because it always seemed to prevent severe injuries regardless of how serious the damage to the vehicles.

It was difficult adjusting to raging taxi drivers yelling in their native tongues and incensed drunken tourists whose only injuries were bruised egos. The cash payout would take care of what we called the “jostle jerks” who often settled for under $500 cash. The hardest cases to settle were bloodied and bruised passengers. In these instances, our protocol was to call Jonny Sample who monitored the police, paramedic, and fire radio frequencies. Jonny’s squad of loyal traffic cops were always first to arrive and began taking statements and writing reports favorable to Zion. Jonny would soon arrive on his shiny police motorcycle dressed in full leather and knee high boots. Once Jonny removed his helmet, revealing his movie star good looks, women and even men became putty in his hand. With his acting skills, Jonny convinced the victims that the accident report wasn’t favorable to their case, and “if the taxi company was offering a cash settlement, he would take it in a second.” Jonny was a pro and these payouts seldom exceeded $1,000 per accident. Jonny could write a report showing Jesus Christ was at fault for an accident.

Nassir was Sy’s driver, general assistant, and bodyguard. I found it ironic that the owner of a transportation company didn’t drive a beautiful car. I guess it was the New Yorker in Sy who was accustomed to grabbing a cab. Sy was tight with a dollar. His taxi drivers complained that repairs were done with rubber bands and chewing gum.

One evening over beers, Nassir had one too many and revealed some of Sy’s background. Sy was a young man breaking into the schmatta trade pushing clothing racks up and down Seventh Avenue in New York in the 1960’s. His family perished in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. In the spring of 1967, tensions between Israel and Egypt were at a breaking point. Sy was determined to honor his lost family so he quit his job and enlisted in the Israeli Army. He rose to the rank of tank commander and stayed to fight in the Yom Kippur War in 1973. He left the army as a decorated officer and returned to the United States, stopping in Vegas for a vacation. Sy never left and built a thriving taxi and limousine business.

Nassir told me Sy never married but had his choice of many beautiful women in Vegas. He lived in the penthouse suite of a swanky casino with 24/7 room and maid service. Nassir pointed out that Sy never seemed to sleep often calling Nassir at any hour of the night for this or that. I asked why Sy chose to live alone in a hotel room with little rest to which Nassir replied, “We all have ghosts which keep us up. Sy has more ghosts than most so he prefers to live where people are only a phone call or elevator ride away to the lobby.”

Nassir told me Stuey started in the mailroom of a large insurance company and rose through the executive ranks. He was fired at a senior executive position due to boozing and womanizing with his secretaries. He moved to Vegas and started an independent insurance agency with Sy becoming one of his first and largest clients at half a million dollars a year in commissions to “Hush.” Sy used Stuey’s knowledge and inside contacts within the insurance industry to negotiate claims and keep premiums down.

Jonny was a washed-up child star who gravitated towards police work. His charm and good looks advanced him through the ranks of a large California police department until he retired. When Sy let the Vegas police chief know he was looking for a sympathetic traffic cop to investigate collisions with his cabs, Jonny was recruited by our police department to run the traffic division. Sy was generous to his gang and they were loyal to Sy.

Mai Tang was one of the most ambitious and shrewdest business women I ever met. I was six months into the job and no longer needed to be on Nassir’s training leash. Anything I couldn’t settle at the accident scene was quickly disposed of by Jonny, Doc, and Hush. Sy’s insurance claims had dropped by two thirds and his insurance premiums were decreasing. The “gang” at the Zion Taxi Cooperative was operating like a “well-oiled machine”. The silver metal briefcase was still two thirds full of cash which made Sy happy but his cough grew more aggravated with each week and his phlegm had traces of blood. I surmised his weight loss and coughing were attributable to lung cancer. I knew he was dying.

One evening I was alerted to an accident between one of our taxis and a van. I arrived within eight minutes to find that our taxi had “T-boned” a van outside McCarran Airport. Our driver was without a fare but the van was carrying 11 beautiful young Asian women. The van was marked with red Chinese characters and the only word in English was “Tours”. Our driver sat on the curb silently as a forty-something Asian woman hounded him yelling in broken English. The jet lagged girls sat silently in the van. Some covered their faces and others had a homesick and frightened look.

I approached the shouting Asian woman, introduced myself as the “accident investigator” for Zion, and suggested that since nobody appeared injured, we should settle the matter quickly at the scene. I had grown accustomed to accident victim theatrics and knew Mai was puffing up the injuries to her passengers. I assessed the settlement at $200 per passenger but Mai would have nothing to do with it. She demanded $5,000 or she would call 911. I handed her Jonny’s business card, showing his status as captain of the traffic division and offered to call him to the scene. I told her that it was Jonny’s practice to summon immigration officials to his accident investigations involving foreigners. Her tone softened immediately and she turned to speak with her passengers in Mandarin. She returned and agreed to accept the $2,400 repeating “No want problem.”

It took me less than 15 minutes to secure the dozen signatures as well as the signature of our driver. As I placed the last $100 bill into Mai’s hands she said “You very clever businessman. Call me. I buy you dinner” and handed me a card reading:

Mai Tang

Proprietor

Slippery Sadie’s Massage

Mai climbed into the driver’s seat and drove away. Slippery Sadie’s Massage parlors were located throughout Vegas and were known to offer sexual favors for the right price. I waited a week and phoned Mai. We agreed to meet at a low key Chinese restaurant off the strip serving authentic Szechuan cuisine. The restaurant was packed with ethnic Chinese which told me the food was good. Waiters took me to a secluded table near the kitchen where Mai sat, tending to a stack of paperwork while drinking tea. She greeted me and motioned for me to sit and then ordered my dinner in Mandarin. Mai said, “Don’t worry. You like what I order”.

Mai was a multitasker. Three smart phones were placed on the table in front of her and two rang throughout dinner. She used one phone to speak English with customers and the second phone to bark orders in Mandarin to her therapists. The third phone never rang and I guessed it served a special purpose. Mai was curious about Zion and my role and I divulged as little as possible. I took the opportunity to ask her about Slippery Sadie’s. Mai was surprisingly frank. She had immigrated to the US on a fabricated visa twenty years and landed a job as a masseuse. She amassed enough savings to purchase her first massage parlor. She expanded her business by cultivating relationships with rich regulars willing to invest in new stores for both the high return on investment and the perks with Mai’s girls. Mai didn’t like partners and always paid them off earlier than agreed.

Mai also operated a sham American-Chinese tourist agency out of a post office box which arranged for young beautiful Asian girls to visit Vegas on a tourist visa where they would go to work in her massage parlors. Mai paid all the travel costs. When the tourist visa was about to expire, Mai would enroll the girls in the local community college “English studies” program and applied for student visas. Her system seemed to be working, and seldom resulted in any immigration complications. Slippery Sadie’s parlors were opening at a rate of one per month, attracting customers with billboards advertisements throughout Vegas that depicted young Asian beauties wearing cowboy hats, chaps, holsters, and cowboy boots.

Mai was overwhelmed by the lease negotiations and landlord tenant disputes because her English wasn’t fluent she and didn’t understand the law. She asked me to review a new lease she was negotiating and it didn’t take me long to find the lease was written in favor of the landlord. I suggested she include free rent, tenant improvement allowance, and massage exclusivity clause in her negotiations. Mai was impressed and handed me the file saying “You handle for me.” She continued taking calls throughout dinner. I found Mai attractive. She was small in stature but tall in moxy. She had an uncharacteristically large bust line for an Asian woman and her figure was shapely. Her hair was long and braided into a ponytail. Her small hands were delicate and adorned with Jade.

I prepared a counter proposal on Mai’s letterhead to her landlord, and he capitulated to all of my demands. For that, I was invited to Mai’s palatial home in an exclusive gated neighborhood outside Vegas. She was wearing a sexy low cut black dress and smelled of Chanel. We enjoyed champagne and caviar poolside. The champagne lowered my defenses as Mai probed about my police and insurance contacts. After dinner, Mai summoned her Chinese servants to bring cognac to the warm bubbling spa nearby. Mai removed all her clothing and entered the spa waving for me to join her. She drew close to me and with the expert touch of a masseuse and a gentle kiss, invited me to penetrate her. The servants returned with plush bathrobes and we retreated to the master bedroom for a rain shower in her lavish bathroom followed by pillow talk draped in red silk sheets.

Mai was quick to the point with her business proposition. She wanted me to handle all her landlord and tenant negotiations as well as any immigration issues. I told her I wasn’t an attorney but I knew my way around the law. Mai also wanted the benefit of my contacts within the police Department. The raids on her massage parlors were infrequent but costly. Mai proposed that we could make big money from insurance settlements if I helped her stage accidents with Zion. She would supply the injured victims from her pool of massage therapists and immigrant community contacts and give me kickbacks from the settlement money.

With Sy dying, I pondered my job security. I told her I would think about it, but she propose a compensation package if I was to represent her business interests. She wasted no time in offering me 25% equity in her new establishments I helped open. I accepted and said I would draft a partnership agreement and LLC on each new store opened. I knew the equity was only a carrot and Mai wanted the big money from the insurance payout scam. I soon discovered that the third phone Mai owned was reserved for communication between the two of us. She would call me day and night and I knew what Nassir felt like being at Sy’s beck and call.

I laid awake evenings thinking about scamming Zion and I couldn’t bring myself to harm Sy. He had become a father figure to me. Then it dawned on me. Although Zion was the largest taxi operator in Vegas, the “gypsy cabs” that refused to join the Zion cooperative, the ride share companies, and the limousines cut into Sy’s market share. It would be a smarter bet to target these operators and leave Zion out of it. To make it work, I would need the help of Hush, Jonny, and Doc. I would also need to disclose it to Sy who would likely want no part of it.

Nassir called me in the middle of the night and told me Sy had been rushed to the emergency room with trouble breathing. He was requesting to see me immediately.

Sy was in a private room. He was ashen gray and hooked up to an oxygen tank. His arm uncontrollably trembled as he reached for my hand and held it with that bear-like grip, but it was weaker now. He removed the breathing mask and told me that he respected me because I had the hustle and the street smarts he had as a young man. He appreciated my drive and desire to learn his business at the expense of my bar exam studies. He told me to pursue the bar exam because I would be one of the great shysters of Vegas one day.

He made me a generous proposition making me chief executive officer of Zion with a 75% equity stake. The remaining 25% would go to Jewish and Israeli philanthropies dear to Sy’s heart. He had a contract ready for me to sign and called up a notary to officiate. He gave me that same shark like stare the day he offered me the job: “Are you in or are you out?”

I said, I’m all in Sy. The contract would take effect immediately. Sy told me that he had a few days to live. When the notary finished her work and we had both signed, Sy told me to convene a meeting of the gang. They would receive a copy of the agreement. I was now their boss but otherwise it was business as usual. This was the opportunity I needed to establish a staged automobile accident insurance hustle which would increase Zion’s market share at the expense of the competition, and enrich the members of the new LLC which included me, the members of the gang and Mai. It would be called “Accident Injury Legal Consultants, LLC.” Sy died that morning, and his body was flown by private jet for burial in Jerusalem. The flags at Zionn headquarters were flown at half staff.

I knew the bar exam was coming up fast but I was so busy doing settlements for Sy and working as Mai’s business manager I didn’t have time to study. I contemplated giving up the law, secure in my new equity in Zion and Slippery Sadie’s. I didn’t need to be a lawyer but passing the bar would make Pop and Sy proud. I went ahead and registered for the bar exam which would be my fourth and final attempt at passing.

Representing Sy and Mai’s business interests gave me real practice in the legal principles of torts, property, and contract law. They were no longer abstract text book concepts because I lived and breathed them every day. When I sat for the exam and read the case studies loaded with contracts, property, and torts principles easy to miss to an untrained eye, I found each of them to be exceptionally obvious. Not only did I see the legal issue at hand, I had well-reasoned answers to each question. I was the first of hundreds to finish the exam.

About a month later, an envelope from the state bar examiners arrived in the mail. I had passed the exam in the upper 95% percentile of examinees. For the first time in my young adult life, I broke down in tears as I held the box of my Pop’s ashes close to my heart, telling him, Pop we’d finally take that ride down Pacific Coast Highway.

After taking my oath at the state building and receiving my State of Nevada Bar License, I set up Accident Injury Legal Consultants, LLC as a law firm and it quickly flourished. Mai staged accidents between Chinese tourists and the livery, ride share, and gypsy cab companies. The ride share drivers were the easiest to settle. They were frightened about the damage to their personal vehicle, liability to their passengers, and doubts about the insurance coverage from the rideshare company. The passengers were also easy marks because they knew they had minimal insurance coverage, and I made it clear the rideshare company would be difficult to sue. I could settle these for $500-$1000.

The harder cases with gypsy cabs and limos would capitulate when Jonny or one of his traffic cops arrived on scene and began finding vehicle code violations, outstanding immigration or arrest warrants on the drivers, and presented them with an unfavorable accident report. Doc’s medical reports and Hush’s behind the scenes negotiations with the insurance adjustors always favored our case. Word spread amongst Zion’s competitors that AILC was the “go to” law firm

for accidents. As I grew to know the ownership of these competing companies, I negotiated buying them out for Zion. We became a virtual monopoly within the Vegas taxi cab business. AILC became the dominant auto accident legal firm in Vegas and I became rich through my

equity in Zion, AILC and Slippery Sadie’s. I never needed a billboard to attract clients!

It was a five-hour drive from Vegas to beautiful Del Mar California, home to one of Pop’s favorite horse racing tracks. Pop and I enjoyed every minute of the long drive in my new red Ferrari with Sinatra playing. The sun set behind the blue Pacific Ocean, the blue sky painted with wisps of orange and yellow clouds.

At the coast, I parked and prepared myself. In one hand, I held a bottle of cognac and in the other; I held the box with Pop’s remains. I opened the lid to the box and as a wave crashed into me just above my knees and I sprinkled Pop’s ashes into the warm blue surf, he was gone forever. I took a swig of the cognac and toasted my beloved father. I also toasted our best friend Sy Hersh. They don’t make fellas like those anymore!

Between my investments in AILC, the Zion Taxi Cooperative, and Slippery Sadie’s, my reputation as a cunning business lawyer spread throughout Las Vegas. I took on clients ranging from Casino moguls to real estate developers. I was a featured speaker at state bar conventions. My legal achievements, native son citizenship, and youth made me an attractive candidate for political office and was courted to run for office.

Every once in awhile, one of the insects crawls out from underneath the diamond and takes it with them.

Wondering a Plenty: Three Poems by Ben Weaver

Wooden Axle and the Wasteland of Trains

Jeffy at the spigot

those eyes like wind through bullet holes

or a sink full of dirty pans

motorcycle clouds

jackstrawed telephone poles.

Went to see the beekeeper

a rope hanging from an oak

leaves on the kitchen floor

her breasts like snow

falling through a torn screen.

Root poems crow footing up her arm

is how the world ends

sister coming home through the corn

old Work Bench Face and his midnight thieves

building the railroads a wasteland.

Out of pine shadows

the re-gather begins to congeal

whispering totems make fire

from scattered orange peels

and boxcars clanking up the moon.

Jeffy up near the engine

singing Nobody Knows the Trouble

shoveling hallelujah from the avalanches

smoke and laughter rise

and once more go between stars.

And so Little Sister protects

the wandering needlework

of the forsythia and the despoblados

puts blue on the rivers and streams

weighted with stones into her many ferny loops.

Those who knew what the forest had in mind

before Wooden Axle rolled up

are standing in the doorways

refusing Old Work Bench Face

and the conquerors entry.

This time the stories will be told by the

rare touchwood and quiet mossery

Jeffy at the 6 burner

Little Sister rolling out the dough

because generosity is how you prepare for a rainy day.

New Great Explorers

We come up in the bottoms

through the brambles,

the streets, and single tracks,

the river carries its shoulders

out through the fields,

every time it rains

crows post on snag wood

and swallow stones

from the holes in an old lightening bolt’s shoe

we are the new great explorers,

we saw the legs off, sit on the ground,

plant water and moon smoke in our

shoulder blades, pedal joints,

we wait in the stems,

like sun light, rope swings

towel less swims

and rooster crows passing in apple trees

we go forward by circles

abounding by and by

as salt from the oceans collects on our skin

going back up cloudless

coming back down again

this time as fishtails and black-eyed peas

we live like coyotes

listening to sagebrush

counting the days between rain

we know the weather by being out in it

know the way, by watching it unravel,

as a white horse shows red dust

or an orange thread pulls forth from a seam.

we are the new great explorers

self-willed, seeds of sun expanding in the shadows

in places where the rivers come together

and the herons listen to frogs and spider webs,

we make the wind exist

make blue sky out of our breath,

through the brambles,

the streets, and the single tracks

we claim the day with our legs

we are the new great explorers

we are the bicyclists.

Bike Shack

String the boot print moon up in the window

scrape some sand and twigs together and sit down

this be my bike shack

fold up a few onion skins

stuff them under the door to keep out the draft

I will light a fire.

Sweep the beans off the counter into the grinder

swear to the swift birds

the river current

them cold-outback stars

You know truth be in the ditch ice

stovepipe pines, wondering snowflakes

and brilliant revolts.

Uncle Whistle Bones and Hawk Eye nephew

toted a canvas bag stuffed with wolverine

and dingo dreams back up to the cave

then lit snag wood and Jewelweed into a pinnacle fire

danced shadows onto the limestone walls

perpetuated freedom, carved songs,

outlaws, shantymen, gandydancers.

Last time, a lightning bolt from sister Chestnut’s chimney

blew a heart through the speckled dawn,

left Gramma out in a rainstorm

clutching porcupine quills and horse bones

swearing to the garden loam

listen here she say,

we better chase the shrieking jays out

and don’t avoid your heart any longer

nor violate your purpose here on earth

it be a dark road

fly down it with light

hold tight, hold tight

now you hear.

And to you sweet single track

dark wood worm, mighty aspen bridge

if we cook, love, and build our adventures

from the limitations of whatever is at hand

the result will always be a surprise

made of its own proportion.

This be so in the shaky morning light

this be so in the stone skipping dusk

with legs all a burn in circles

this be the way, this be our lost trail

dog hearts of thicket, wondering a plenty

the land is everlasting.

River Bottoms

Braided Creek

Manitou

Chequamegon

Sawtooth

Crosby

Black Dog

Shoot those gullies full of half-moons and steelhead

tell the kids I went chasing stumps

hunting mushrooms among mossy rocks

riding the hills to let the wind be known

winding back down the long way home

fog and tea leaves, rose and cabbage

only a few lost rovers will find it

tell them, this be my bike shack

stay long as they want

can’t say when I’ll be back.

Alexander in Mid Air

by

Agnes Bookbinder

thumbnail art by Rene Castro

I.

Alexander has a second to think before he begins falling, but he chooses not to use it. He doesn’t begin thinking immediately after he begins falling, either.

It is only a matter of time until he is no longer falling, so he settles into the air to enjoy the view. The horizon remains consistently horizontal in the distance, a fine flat line where the sky and the water meet. The setting sun spreads across the water like orange marmalade. So flat. It makes sense the horizon is flat. It is no coincidence that horizon and horizontal sound the same.

“There’s proof the Earth is flat,” Alexander thinks sagely as he clears the promontory. “Mr. Ivan said it would be, and it is. That’ll show ‘em. The moment of truth!”

Any minute now, he will lose this heavy sinking feeling. The air is messing up his hair. He tugs at the few loose strands that still cling to his scalp and smoothes them. They won’t behave. Alexander is aware there is a camera watching him up above. Perhaps they can fix his hairs when they edit the video. Maybe they can give him a fine head of hair like Mr. Ivan wears. They can do amazing things with cameras these days.

The errant hairs tickle his ears like taunts, but it will be worth it soon. He will slow and then float off into the sky, like a balloon. Even if he hasn’t been covered in enough magnets to float away, there is an inflatable dinghy waiting for him down below that will catch him when he drifts down and will carry him away a proud victor. His hair will do what it is supposed to do. When he slows.

Any minute now.

Any minute now.

Alexander sighs. This is taking too long.

He chastises himself for being impatient. Mr. Ivan didn’t say how long it would take. If Mr. Ivan has faith in his ability to prove the doubters wrong, the least he can do is wait a bit before so-called “gravity” releases him. He is not close enough for the magnets to interact with the water anyway. Squinting down, he can make out the assault of the white seafoam against the cliff below. He wonders if the waves will thrash harder as he nears, the water irritated by his magnet suit.

A seagull flies by and gives him a startled look, like it can read Alexander’s mind. Alexander shoos the seagull away. A seagull reading a man’s mind is unnatural.

“If I want a bird to know my thoughts, I’ll holler at it, like nature intended,” Alexander thinks.

II.

“The first thing you must understand is that Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein were clever, but they were wrong. They used math to confuse people,” Mr. Ivan tells them on the video. “Everything they taught you in school is a lie.”

Mr. Ivan is an impressive man, tall and confident in his wool suit. Alexander stares at his teeth. They line up in perfect proportion. The white of his smile matches his starched shirt. His hair, a rich black that shines blue in the light, is as resplendent and full as his smile. Each hair obediently sits where it is meant to sit.

“He must know what he’s talking about to be so successful,” Alexander thinks, adjusting his body in his chair to improve his posture. “And he’s right about math. It is confusing. People say it explains things, but I don’t understand it at all. How well does it explain things if I don’t understand it? That’s a pretty bad explanation if I need someone else to explain it to me afterwards.”

Mr. Ivan’s voice continues. “There is no gravity. There is no invisible force there to pull you down.”

“Then how come we don’t float off into space?” Alexander wonders to himself, watching the monitor. It would be nice if nothing pulled him down. He avoids the eyes of his wife in the framed photo she hung on the wall by the computer.

“Now, I know some of you are probably wondering, why don’t we float off into space?”

“Yes!” The word escapes from Alexander’s lips with great force. It’s as if Mr. Ivan can read his mind through the monitor.

Alexander’s wife, Dina, calls from the other side of the door. “You okay in there?”

Alexander hits pause. “I’m okay! What are we having for dinner?”

He waits for a few seconds, hoping she says hamburgers instead of quinoa salad or something horrible and flavorless. No response comes. He could die in his desk chair and Dina wouldn’t notice for weeks. He hits the pause button to start the video again.

“There are many reasons we don’t float off into space. First, we are less buoyant than the air …”

Alexander looks down at the paunch nestled under his once-black, now-dull grey tee shirt and nods.

“Second, there is electromagnetism. We all know how magnets work. We learn about it in science class in school. That part, they didn’t lie about.

Electromagnetism, without going into too much detail, keeps us safe on Earth.”

Alexander grips the arms of his chair. Solid. He has often felt like the desk chair has a magnetic draw for him, as though it requires extreme effort to lift himself from the soft black cushion. Laziness isn’t the reason after all, according to Mr. Ivan. He will tell Dina it is definitely electromagnetism whenever she makes dinner, which will hopefully be pizza or something good.

He listens to Mr. Ivan for a while longer, before he wanders off to discover he will be eating tofu stir fry for dinner against his will. Mr. Ivan’s voice is soothing, like

Charlton Heston’s voice in The Ten Commandments. He makes his points with ease and authority. Here is a man he can respect. Here is a man he could listen to again and again and will in the days and months to come as he learns about the real science of the Universe. He will even get to hear Mr. Ivan’s voice in person once or twice while the Moment of Truth (now capitalized and formally named) enters the planning phase.

And this is the voice Alexander hears as he falls and remembers in a few brief moments that first day when the world finally made sense to him.

III.

“I wonder if I’ll fall right through the Earth,” Alexander thinks in a moment when Mr. Ivan’s video goes silent in his head. The wind picks up and is whistling chaos in his ears. He probably won’t fall all the way through the Earth, not unless he wasn’t as committed as he needed to be to his diet. They had accounted for the buoyancy of the magnets when figuring out how much buoyancy he needed to lose. The paunch from the first day he heard Mr. Ivan speak is nothing but loose skin now, held down by parachute-fabric pockets filled with magnets. They measured his buoyancy before he jumped. He will not crash through the Earth.

The fall is taking a long time to slow, and this delay has distracted Alexander from the historical importance of what he is doing, he realizes. Mr. Ivan would be disappointed to know he is experiencing doubt. He would give him that half-smile he gives when talking about ignorant people. Mr. Ivan would remind him in jovial tones and hard eyes, “Doubt is like gravity. It does not exist when you know the truth.”

And this is the Moment of Truth. Mr. Ivan selected him to make the demonstration to the world. There is no room for doubt, so Alexander has no doubt.

He has time, though. There are only a few flat stripes in the sky now, so he can’t pass the time looking for shapes in the clouds. He turns, as well as he can turn in midair, wearing a heavy magnet suit with wind pushing at him, and examines the cliff wall sliding past him. Rocks. Lots of rocks. Rocks wearing socks. Rocks, orange-brown like a fox. Rocks made out of blocks.

He looks below his feet. More rocks and, out of the corner of his eye, the inflatable dinghy. The rocks are difficult to see directly beneath his tennis shoes, and one of his shoelaces –the right one –has come untied. The two ends of the laces flap in the wind like his hairs. Alexander would like nothing more than to reach down and retie them, but the magnet suit prevents him from bending comfortably, and he would probably flip over head first, which would be disorienting. He is not participating in the Moment of Truth to be disoriented. He is finally oriented in the right direction, for the first time in his life. He ignores the obvious flapping of his laces.

Alexander turns his head to the left and sees the dinghy in full. The yellow of

the small boat is fading to a muddy phlegm color as the evening approaches. He sees the pilot’s face. What is the name of the man? Tim? Tom? Something like that. He has an expression on his face like a startled rabbit, as if he would rush off the boat if he weren’t surrounded by water. This confuses Alexander. There is nothing startling to see. The rocks are as dull as sticks and dry leaves, and even the waves are becoming boring in their regularity. Not scary at all.

A realization dawns on Alexander slowly as the rocks and the dinghy grow quickly.

Thump!

A gasp.

“Dina’ll miss me tonight,” he thinks as he loses consciousness. It grows dark overhead, and the ether turns black.

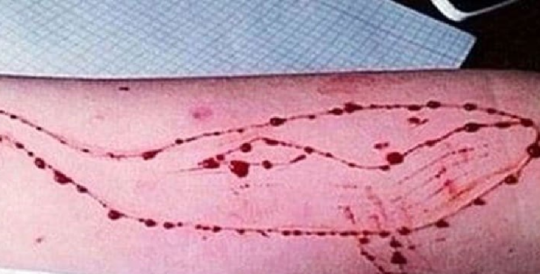

Ballena Azul Suicide Game Spreads to Latin America

by

McKenzie Ingram

photo credit: Cedoc

Santiago, Chile. 9 April 2017.

While most childhood antics seem innocent and fun, a game with suicidal tendencies has come to the attention of the Chilean public that is cause for serious concern.

Ballena Azul, signifying Blue Whale in Spanish, is a suicide game that originated in Russia and has spread through social media to numerous Latin American countries.

Named for the marine species that draws close to the shore when it is prepared to die, Ballena Azul consists of a series of fifty challenges for kids from approximately twelve to fourteen years old. These challenges include staying awake for extended periods of time and cutting the shape of a whale into the participant’s arm, eventually culminating in suicide on the date determined by the coordinator of the group.

The game was invented by twenty-one year old Philipp Budeikin, who claims he created the game to rid society of “biodegradable waste” who threaten the well-being of others (debate.com). He stated in his interview from prison that his game gives participants the “quality, comprehension, and communication” that they otherwise lack in their lives. In 2016, he was linked to the suicide of 130 children in Russia and found guilty of organizing eight “death groups” with suicidal intent.

According to Telesur, there are currently thirty-one Ballena Azul victims in Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, and Uruguay and over 18,000 followers of the Spanish-speaking Facebook group alone.

Seven known cases of Ballena Azul presently exist in Chile, including a pre-teen in Antofagasta with more than fifteen lacerations on her arms. While the participant’s mother initially denied her daughter’s involvement, the twelve-year-old later admitted that a friend from her previous school had introduced her to the game through social media.

Two of the other Chilean cases were contacted and threatened by a group coordinator to join the suicide squad, while the remaining kids discovered Ballena Azul through their own efforts.

One boy in Coronel, Chile, falsely proclaimed his involvement in Ballena Azul as a childish stunt to get more Youtube followers, further revealing the vulnerable social nature of Ballena Azul targets at such a young age.

With the rising popularity of television series such as “13 Reasons Why,” which graphically delves into the people and situations that lead the fictional character to take his own life, the dangerous messages of technology today are certainly normalizing previously taboo topics, for better or worse.

Because of the headlines provoked by Ballena Azul, Chilean President Michelle Bachelet recently launched a national cybersecurity plan to exemplify Chile’s democratic values and educate the public on the dangers of technology and how to best utilize this resource.

According to psychology researchers Tomás Baader Matthei and Francisco Bustamante Volpi, Chile has the highest adolescent suicide rate in Latin America (El Mercurio).

While community and state-level organizations such as the National Program of Suicide Prevention and Chilean Alliance against Depression are currently attempting to fight against suicide’s dramatic national presence, more than mere coalitions will be needed for suicide to relinquish its suffocating grip on the country.

So, who or what exactly is to blame for the rise of Ballena Azul in Chile?

Social media and the evils of the modern age?

Mental health predispositions?

Early exposure to technology?

Parental negligence?

Peer pressure?

While it may be tempting to look for an all-encompassing cause or culprit for Chile’s recent surge in adolescent suicide, this effigy of despair has more likely been constructed and edified through a combination of some or all of these factors.

All the blame cannot rest solely on parents, technology, or the government, because rising suicide rates and the parasitic presence of Ballena Azul in Chilean culture is a systemic issue.

For this reason, searching for a scapegoat will not fix the problem at hand; however, joining hands across borders, organizations, and communities to confront this issue from multiple angles will begin to eradicate the presence of suicide from Chile.

It certainly seems that the first step to lift Ballena Azul’s heavy burden from the hearts of Chilean people would involve removing the inherent stigma of suicide so that an open dialogue can finally begin to take place.

There is a comment section below if you would like to start that journey.

April 24, 2017

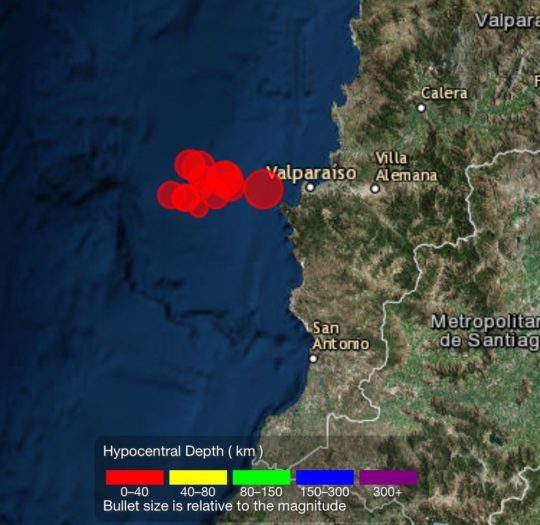

7.1 Earthquake Rocks Valparaiso and Viña del Mar Chile

18:38 Viña del Mar, Chile. 24 May 2017.

A strong 7.1 earthquake just hit here in Chile. Here in this coastal city is the 2nd large quake we have had in three days. Saturday night people were heading for the door in a restaurant near the casino when a 5.9 quake hit. Here in Chile people are accustomed to this. Tourists are the ones who usually run out as they are not used to this.

Here in the building where we are writing this some items were tossed to the floor. On the 7th floor the shaking was strong. People in Santiago felt it strongly as well. Lights and water are still working except for some sections of Valparaiso and Con-Con.

TVN news says SHOA ocean service canceled evacuation and that there was no major damage nor injuries. Valparaiso metro shutdown.

Today’s and Friday’s quakes were very shallow and close to the city (10 km deep and 25 KM west). Usually the quakes here are much deeper as the Nazca Pate pushes underneath the South American plate unlike California where on the San Andres fault one plate slips pass the other. Subduction type quakes are more violent.

This quake was accompanied by much ground noise. According to the University of Chile, in Chile there are 3 major earthquakes of this intensity per year. To put this in perspective, the 2010 7.0 quake in Haiti killed over 100,000. In the 2010 8.8 in Chile 500 people were killed by the resulting tsunami, the warning of which was not passed to the people due to an accident in communications. The 1960 9.6 Valdivia quake was the largest in recorded history worldwide.

There are multiple aftershocks that you can follow here. The University of Chile also sends it data to the Euro Med website here.

UPDATE 20:27. Santiago, CHILE.

The 7.1 earthquake (USGS) that hit the coast of Chile just over an hour ago is now registered at a 6.9 by Chilean authorities. It shook Santiago much less than its counterparts in Valparaíso, Los Vilos, and Linares. While these tremors are quite normal for Chileans, even in Santiago, people were screaming and running in fear in the downtown area of the city. The only damage caused by the seismic activity in most parts of Santiago were rattling household objects with very slight falling material.

These seismic events are by far the strongest of the past six days in the central region of Chile. Citizens in this region will likely be looking out for further aftershocks for the next few days.

April 21, 2017

Argentina Shuts Down Transport: Don’t Blame Pepsi

By

Jonathan R. Rose

What can be said about The Pepsi ad that hasn’t been already said?

A lot, actually.

But what can be said has little to do with Pepsi itself. Pepsi did not commit a crime. It did not even lie. It perpetuated a stereotype.

The commercial they put together didn’t convey imagery conjured from thin air. It just grossly exaggerated some of the superficial images that anybody who has been to a protest in the United States has already seen, while completely ignoring any images involving the inherent violence or anger they have most likely seen as well.

In the commercial, the people were prettier, the signs were more ambiguous, the music had better sound quality, and a model gave a cop a can of Pepsi. But other than that (and the complete disregard for anything remotely negative), what was really different from an actual protest seen in the United States?

Blaming Pepsi for perpetuating the stereotype they chose is the same as blaming a comedian for making jokes about a stereotype they have seen, heard about, or has had direct experience with. But blaming the perpetrator of the stereotype is always easier than changing the nature of the stereotype itself. And while people deserve credit for putting forth the necessary effort to have the commercial removed after a single day, the question now is how much effort will be put into changing the stereotype that led to the commercial’s creation in the first place?

Stereotype based expressions can make people uncomfortable, especially when they get too close to the truth, and Americans seemed to be incredibly uncomfortable after watching that Pepsi commercial. Was that because the commercial was too close to the truth?

People in America were offended at what the commercial showed, many of whom for good reason, but that is not the point. The point is regardless of how uncomfortable, how offended people were, that doesn’t change the possibility that their discomfort and offense resulted in seeing the truth, or at the very least, a portion of the truth they did not want to see. If that is the case, it is but a first step to blame the person, or the company in this instance, for showing that truth. The second and much more difficult step however, is to blame the source of that truth itself, even if that source is yourself, or somebody you know, or somebody you respect, or somebody you love.

If Americans are so angry about the imagery they saw in the commercial, then they need to change the source of the imagery itself, not just settle for blaming the corporation who tried to profit from it.

This leads to an interesting event that occurred on April 6th throughout the country of Argentina.

After a month of constant marches and protests, most of which were similar to those seen throughout the United States, as they were filled with people holding signs, chanting slogans, blocking streets, and demanding change, the people throughout Argentina, organized and led by several unions, took things a step further. They carried out a strike that completely shut down all public transportation throughout the country, not the capital city, not a whole province, but the whole country. From subways to buses to trains to flights, both national and international, everything stopped. The only exception was taxis, and only a section of them were on the roads.

In the current state of American unrest and dissatisfaction, while it’s crucial to look inward, it is of equal importance to look outwards as well, which means looking beyond borders to see what people in other nations are doing to oppose the leaderships they deem unjust.

In Argentina, many of the people are not happy with the actions of their current leadership, but instead of just marching with signs and shouting slogans, in essence portraying the stereotype that Pepsi deemed acceptable to exploit, they took things further. What will they do next? How much further are they willing to go? And what will the government they are so openly defying do in response? These are the important questions. These are what should be the topic of discussion when it comes to public defiance, not just how to stop a soda company from ridiculing the actions already taken.

When a company like Pepsi is shamelessly mocking your actions, it’s easy to get mad at them for it, but it is also a clear indication that the actions they mocked need to be changed.

Just imagine if Americans shut down all of the public transportation throughout the United States for a single day?

They did it in Argentina.

April 15, 2017

Woke Up This Mornin’

by

Stephen O’Connor

thumbnail artwork by Rene Castro

Lee Van Dinter woke up early, with the beginning of a song running through his head. The others, “my associates,” as he referred to them, were still lying on the rows of cots around him, like so many piles of ragged wheezing laundry—stinking shapeless lumps, from which protruded bony arms and wiry beards. He sat up and tried to remember the lines that were left when the dream dissipated.

Those Charleston Manville bells don’t ring . . . those Charleston Manville bells don’t ring.

Been here two years I know one thing

Charleston Manville bells don’t ring.

Where the hell did the dream come up with Charleston Manville? Was there such a place? He didn’t know. He slipped his feet into his shoes. You sure as hell didn’t want to walk barefoot in this place. He pulled his “old kit bag” from under the bed, took his toothbrush and toothpaste from the side pocket and wended his way through the maze of cots to the bathroom. Goddamit, in the old days—the old days, shit, two years ago, he would have taken his guitar, his coffee, and a pad of music paper out on the deck, sat there in the sun and wrote the song. “Ain’t got nobody to blame, asshole,” he said to himself. He pissed and brushed his teeth—took off his flannel shirt and tee shirt and washed up as best he could, wet down his hair and shook his dripping head, staring hard at the grizzled figure in the mirror. He’d shared a bottle of Old Ezra with some guys at a campfire in the woods along the tracks under the overpass. They said it was 101 proof, if that was possible. “Somewhat leaden, and moth-eaten this morning, Van Dinter.” He wondered if it might be better in the long run to go back down to the tracks, wait for a train to come by and jump in front of the sucker. Oh yeah—fear no more the heat of the sun, nor the furious winter— something. He decided against that because it would be messy as hell and he didn’t think he was ready to cash in his chips just yet. Anyway, he had a song to figure out, and that’s a reason to live.

Janey was reading the paper in the kitchen, and another bum was sitting at a table drinking a coffee and looking out the window at the dirt parking lot. “Ya wantsum toast?” she asked.

“Just a coffee, Janey. Little milk, no sugar.”

“Come ovah hea and gedit chaself.”

“OK. And would you get my guitar? Frank lets me leave it in the office.”

“Shor, Lee, but don’ play it in hea yet.”

“Can I play it softly?”

“Not yet.”

Once again he remembered the deck at his home, the forfeited home, where he used to write songs. “I had a house in the Highlands here in Lowell, you know,” he said as he poured his coffee. “Jesus, I wish I was back there.”

“Well, ya not the firs’ guyda loozha house over a boddle.”

“No shit.” He drank some coffee and said, “I had a wife. I guess I have a wife still. But –”

Janey was reading her horoscope and he could see she didn’t really give a fuck about his wife or his life. Why should she? He finished his coffee quickly because he remembered his wallet was in his bag under his cot, not that there was much to steal in it. He asked Janey again to get his guitar, and she tore herself away from the funnies. When he had the instrument, he thanked her for the coffee and went and folded his blanket, pulled his wallet and his Swiss army knife out of his bag and left the shelter, snatching a pencil and a junk mail envelope off the front desk on the way out.

It was a brisk and sunny morning in late March, something like Joni Mitchell once sang about in that song about Morgantown. Even the faded green and half-rusted struts of the overpass looked fine, and the smokestacks of the old mills were works of art, towering industrial monuments to a long-vanished working class. He recalled Jack Dacey, the house philosopher down at McCullough’s Bar saying, “It’s amazing how those smokestacks were all built in a perfect circular curve, even though the bricks themselves are not curved. And,” he said, “the whole structure tapers as it rises.” His hands had risen up and converged as if he would join them in prayer. They had agreed that those dudes were badass engineers, not to mention the balls on the masons that climbed up there in 1890 or something to lay the bricks. Christ, you wouldn’t want to be up there with a hangover.

He laid the guitar case down on a bench on Jackson Street by the stone-walled canal, lit a cigarette and sat down beside the instrument – two old pals, he thought. He flicked the five snaps open and picked up the guitar by the neck. Addressing himself to an invisible audience seated over the canal, he said, “She’s a 1947 Martin, 00-17, all mahogany body with a tortoise pickguard. Yeah, she’s a beauty folks, and like the song says, she’s all that I got left.”

He tucked the cigarette between his lips and strummed a few chords. He pulled a two-pronged tuning fork out of a compartment in the case and rapped it on his knee, placing the end against the soundboard; a perfect A tone rang out like a bell, and he tuned the A string to it, then twisted the other tuning pegs until he was satisfied. Most players nowadays used a Snark tuner that clipped on the head of the guitar and tuned by colored light bars, or they used some kind of cell phone app, but Lee had faith in time-honored methods. Robert Johnson sure didn’t need no colored light bars. Lee didn’t have a phone, but if he did, he wouldn’t use it to tune the damned guitar. He laid the smoking butt on the bench, and began.

Been here two years an’ I know one thing

Those Charleston Manville bells don’t ring

He sang the couplet over three or four times, picked up his cigarette, took another couple of drags, and laid it down again. He looked across the canal and up at the old cotton mills—the endless rows of windows suffused with pink in the rising sun. He thought of the men and women who for so many years had answered the bells that now sat dumb and rusting in their worn cupolas, and of the workers who climbed the great winding staircases to stand for years on end at the clanging looms—weave and spin, weave and spin. He remembered Nick, the old Greek communist, who asked him, “In what three places you hear bells?” Lee said he didn’t know what the hell he was talking about, but the Greek said, “In prison, in school, and in church, you see? The prison is the prison of the body, the school is the prison of the mind, and the church is the prison of the spirit.” Crazy old Greek almost made sense sometimes.

Been here two years an’ I know one thing

Those Charleston Manville bells don’t ring

Three men killed in the miners’ riot

But Charleston Manville bells are quiet.

Yes, the bells are quiet ‘cause they don’t give a fuck when workers die; they just call ‘em to the factory, to the mine, call ‘em to church. Like his great Aunt Clara—she answered the bell for thirty years in the Lawrence Mills, and on the day she retired the goddamn boss couldn’t even bother to come down to the floor to shake her hand. Lee’s head bowed over the instrument and a mournful sound rose, blues licks in the key of A minor. He bent the strings as he played, the way old Josh White and the great bluesmen taught us all. He listened for and found the chords, A minor 7th, D minor 7th, F and E7th. He wanted that ‘St. James Infirmary’ feel. That song knocked him out when he first heard it, like so much of the blues he loved, on a Josh White record. Josh was a dignified-sounding blues man, and a great acoustic player.

He took the pencil and the envelope out of his pocket and began to jot down notes to himself. He knew the chords, but he was working out the verses, singing softly, humming, trying variant lines. He cut Charleston Manville down to Manville. It wasn’t a riot— it was a mining disaster, and the whole piece was morphing from a bluesy number into a more traditional ballad, like “Little Musgrave.” Within fifteen minutes he had worked out the first two verses, and sang them over a few times to fit them to the melody: