Nicole Rollender's Blog, page 4

June 20, 2016

Carpe Noctem Interview With Meg Eden

NEON, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

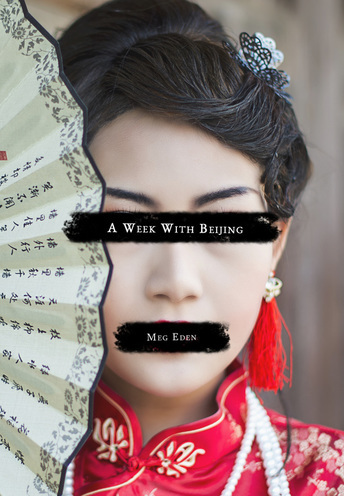

NEON, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Title: Initially the poems were just narratives about my experience going to Beijing in late 2005. However, as I edited the poems, Beijing was no longer the landscape for my poems, but a character I was interacting with. So when that transformation happened, it made sense for the poems to be “a week with Beijing” as opposed to “a week in Beijing.”

Cover: My editor at NEON, Krishan, gave me a few image ideas for the cover. I really liked having a female in the image, and I really wanted some sort of censorship to happen in the cover, as the poems confront the silencing Beijing put upon its citizens before the Olympics (and beyond). So with the image of the girl, we decided we could censor out her eyes and mouth and put the title there. I’m very happy with the end product.

Three-word summary: personified political travelogue.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I wanted to recreate the culture shock and exchange I experienced travelling to Beijing. Most of the trips I’d been on before were very tourist friendly. Everyone was welcoming and provided a “dressed-up” version of their culture to satisfy our consumerism. But when I went to Beijing, the city was “still putting on its makeup”: it was building the Olympic arenas, ripping down the historic Hutong regions, and it was the dead of winter so there were few tourists to cater to. In fact, when we first landed, our taxi driver first said, “What are you doing here? It’s not the Olympics yet.”

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Once I had the idea of exchanges with an anthropomorphized Beijing, the poems came out easily. Revision strategy? I read through all of them in one sitting, make a couple changes at a time, and do that several times.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I think because this was a narrative experience, I tried to create a narrative arch with this collection: set up the situation, heighten the tension to a climax, and (sort of a) resolution.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

For me, a poem needs to haunt the reader. So I look for an image, a moment, that surprises and possibly disturbs me, but it makes me think longer and deeper about a situation. This is both in how I read and write.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This is one of my favorite poems to do at readings. I think it paints a complexity for Beijing “coming of age” for the Olympics. It’s one of the later poems I wrote for the collection.

Beijing Explains Her Twelve Year Old Gymnast

She isn’t twelve, she’s sixteen.

Her name is He Kexin. She was in

the Olympics before but now

is retired; too old.

No one believes me—you think

we want to look so young?

That we don’t want American

breasts, full Western hips? And lips?

I have no daughter, but if I did

she would fly like He. She would live

in the air, and only come down

to eat moon cakes and taunt us.

She would be afraid of no men,

and no men would enter her.

Her body would be tight

like a branch, unbending

but beautiful—no one would

educate her, she would sing

too loudly. She would not be known

by name, but by the way her legs

whip through the air like a bird.

The way she vanished so young

without demands, without fathers

to condemn and harness her wildness.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Probably something to the effect of: I’d bet you can actually read these poems and understand them (and maybe even enjoy them!). I seem to encounter a lot of people, who in response to me saying that I’m a poet say, “Oh I don’t read poetry. I can’t understand it.” As a rather narrative poet, this aggravates me to no end—what are English teachers making their students read? Whatever it is, it needs to change, because it’s scaring everyone away from the world of poetry!

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I could say a lot on that—but in short, to me being a poet is being a witness to something intimate, personal—and in many ways spiritual. What scares me most about being a writer is being a poor or unfair witness. What gives me the most pleasure is to testify to something in a way that's pleasing in both craft and content, and that provides a turn of surprise.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I find everything as fuel for my poetry. When I was working in scientific research, scientific articles provided inspiration for poems. Now, I’m reading quite a bit of academic articles for literature in translation. Writing-wise, I also write fiction, so everything I am reading and writing may return back into my poems.

What are you working on now?

I have a novel coming out in 2017, and am trying to figure out which novel to work on next. I’m also working on a full length manuscript of poems about the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Just finished Jane Shore’s That Said, Susan Morrow’s The Dawning Moon of the Mind, and C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, which were all amazing. Also reading Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokemon by Joseph Tobin which—for anyone of my generation—is a fascinating read, and Sarah Well’s Pruning Burning Bushes.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Ocean Vuong, Naomi Shihab Nye, Patricia Smith, Danez Smith, April Naoko Heck.

***

Purchase A Week With Beijing.

Meg Eden's work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Poet Lore, and Gargoyle. She teaches at the University of Maryland. She has four poetry chapbooks, and her novel Post-High School Reality Quest is forthcoming from California Coldblood, an imprint of Rare Bird Lit. Check out her work at: www.megedenbooks.com

Meg Eden's work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Poet Lore, and Gargoyle. She teaches at the University of Maryland. She has four poetry chapbooks, and her novel Post-High School Reality Quest is forthcoming from California Coldblood, an imprint of Rare Bird Lit. Check out her work at: www.megedenbooks.com

Published on June 20, 2016 04:45

June 8, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Neil Elder

Cinnamon Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Cinnamon Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Primarily the collection explores the gap between what we think we know and what we actually know about other people. The title, Codes of Conduct emphasizes the idea that runs through the collection that we are all expected to behave in certain ways. Those patterns of behavior, the conventions that exist in society, come from all aspects of life – from family and loved ones, from ourselves and from the world of work or whatever roles we are fulfilling. We expect certain actions and thoughts from others, because by and large we are conventional. The cover is part of the Cinnamon Press house-style for the pamphlets that win their pamphlet competition.

What were you trying to achieve with your collection? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Wow, that wants a long and involved response that shifts whenever I consider such things. My main concern is to explore the difference between what we think we know about people and what we actually know about them. I say in readings that people may look at their colleagues differently tomorrow, but the poems could just as easily be asking what you think you know about your neighbour and what you actually know about them – or even what you really know about your husband/wife, or perhaps yourself!

The pamphlet divides into two parts; the first part is a sequence that concerns a figure called Henderson and his world of work, the second half are stand-alone poems, that develop notions about how we communicate. Across the first half Henderson and some of his colleagues filter in and out of the poems. The poems cast a wry look at work and the ridiculous aspects of it, such as jargon and the notion that setting targets makes people more effective. At work there are perhaps certain assumptions made about people based on their role but these often miss what an individual is really like.

Through the character of Henderson I challenge the idea that getting to the top is what we all want. In the second half of the book some of the big themes – relationships, death, parenthood get an airing – you can’t have a book of poems without love and death, can you?The poems combine sharply observed humour and pathos; which seems to me to be what life contains.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

The catalyst for half the collection is a poem called "Restructuring," which effectively points out the weasel ways and words of management, when euphemisms are used to try and soften something that is actually pretty painful and brutal. In this poem, which is set in an office, I suggest the lives and characters of some of the employees. I think this was the first time I really discovered the freedom and flexibility offered by employing characters; there is a touch of the fiction writer involved in this. I then managed "Open-Plan," which is the first poem in Codes of Conduct and which firmly establishes the disconnect between our assumptions about people and the reality. In this poem, Henderson, seemingly a straight-forward office worker, is revealed as having quite a daring and exciting side to his life away from work. I wanted to know more about Henderson and he stuck in my head and I worked on him. At some point I had perhaps three or four Henderson poems and an editor, who saw these poems, asked if there was going to be a longer sequence. I didn’t know how many I’d write, but I ended up with fifteen. What I did find was that once I had the setting, then scenarios suggested themselves: someone retires, someone has a birthday, there is a fire alarm. Thus I had a firm scaffold upon which to build and I never felt like I was starting from scratch – there was enough of a pre-existing landscape to feel I had some momentum.

Meanwhile I would be writing other pieces, away from Henderson. These pieces were slower to come because I didn’t have the framework. However, I did find that ideas about identity and how we communicate were clearly coming through, just as they do in the Henderson pieces.

The revision of the poems is fairly constant – that thing of a poem is never finished, merely abandoned. I start with handwritten drafts and when I feel a poem has some chance of working I move to typing it up. That can alter line endings and all sorts. I then print off the draft, and more tinkering will happen. Some of the poems have been part of workshops I regularly attend with a group – people stamp on the poems and I work with what’s left!

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

It is possible for the Henderson poems to be read as individual pieces and in any order, but there are some elements that suggest a narrative arc; those elements were the ones that dictated the order in the first half. Part two of ‘Codes of Conduct’ has the pace, length and tone of the poems in mind. I have seen photographs of poems laid across the floor as a means of finding a structure to a collection. I suppose that can work, but the irony is that most people read collections of poetry in their own order, dipping in and out – that’s one of the joys of reading poetry. However, I suppose that listening to Sgt. Pepper on shuffle must be detrimental to the whole work, and so we should perhaps be more willing to start at page one of a poetry collection and read on until the end.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

The things in poetry I like to read, and in the poems I hope to write, are a surprising turn of phrase, an original image or way of seeing things. I am not a huge fan of deliberately obscure clever-clever poetry, and so I suppose a certain immediacy is what I want. In Codes of Conduct I think I have the familiarity that makes people smile and nod as they read, but also I pin ideas with a particular phrase or present something from a side-long view that offers the element of surprise or keeps things feeling new.

6. Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The poem I am providing here, "On The Floor," comes from the second half of the collection, and perhaps captures the humour of the pamphlet, but also clearly has communication and our understanding of each other at its heart. I wondered about using the first Henderson poem, but I have had a good reaction to ‘On the Floor’ and at readings I tend to open with it. There certainly seems to be something in the poem that people identify with – that mix of desperation and frustration – feeling misunderstood and not quite knowing how to communicate ideas to others. This poem first appeared in the lovely magazine ‘The Interpreter’s House’.

On the Floor

I would like to lie down on the kitchen floor

and howl like a dog.

What stops me is the thought

that if you walk in just as I let out a yell,

all sorts of awkward questions may be asked.

But then again, perhaps I am mistaken

in judging your reaction

to this scene -

maybe you will join me,

primal, foetal, brittle

and take your place upon the Lino

so that we can tell each other

exactly how we feel.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

That Codes of Conduct will have thoughts and ideas that they have had, possibly without even realising. That there will be a response and recognition on an emotional level to the poems. That the work is very accessible and not hearts and flowers or obtuse. And that they will find themselves laughing – that’s got to be good.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

In many ways I think writing poetry is my equivalent to crosswords or Sudoko and such things that other people do to keep the mind active. There is also a level of challenge – “Okay, I’ve got half an idea, or I’ve got an opening line – now can I make it a decent poem?” There is also the more elusive aspect whereby I perhaps find it cathartic to write about something, but I don’t tend to set about the task in such an obvious fashion. I suppose the fear is that nothing else will come to me, or if it does it will be no good. I think perhaps the ‘correct’ answer concerning pleasure is that the act of writing itself is rewarding, and that is true, but knowing people have read and enjoyed my work is pleasing. Of course the pleasure comes in people saying nice things, but more than that I find the notion that I have made them see something in a new light or from a different angle particularly rewarding – that is often in the quiet nod of a reader, though of course I’m rarely around when they actually read my stuff (that would be weird!).

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Nothing consciously triggers my poetic reflex but I do read a lot of poetry and that percolates somewhere in the mind.

What are you working on now?

A large part of me hopes I don’t know what’s coming next – I want the line to strike me in a lightbulb moment, but things don’t work like that usually. I have a sequence up and running that involves a couple of young women, Ellie and Tara, and through them I suppose I am making observations on life, in particular the way we look at each other – ‘look’ in all dimensions, I mean.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

They Came Like Swallows by William Maxwell. He writes such beautiful prose and captures the sense of things, the mood and feelings in the air, without pushing so hard that the spell gets broken. The inner-thoughts and private lives of characters are so wonderfully explored. Pretty much any William Maxwell should be in your house, but this is so delicate it needs to be treasured.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Edward Thomas, Paul Farley, Lorraine Mariner, Andrew Motion, Philp Larkin

13. What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Any tips for budding poets? – Join a writing group/workshop – the constructive advice of trusted others is invaluable.

***

Purchase Codes of Conduct from Cinnamon Press.

Neil Elder has had poems published in various magazines and journals, among them are The Rialto, Prole, Acumen, The Interpreter’s House. In 2015 Neil won the Cinnamon Press Pamphlet completion with ‘Codes of Conduct’. Neil lives and works in N.W London. He is a member of Herga Poets and enjoys giving readings. Read Neil’s blog and some of his poems here https://neilelderpoetry.wordpress.com.

Neil Elder has had poems published in various magazines and journals, among them are The Rialto, Prole, Acumen, The Interpreter’s House. In 2015 Neil won the Cinnamon Press Pamphlet completion with ‘Codes of Conduct’. Neil lives and works in N.W London. He is a member of Herga Poets and enjoys giving readings. Read Neil’s blog and some of his poems here https://neilelderpoetry.wordpress.com.

Published on June 08, 2016 13:54

June 1, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Marilyn McCabe

The Word Works, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

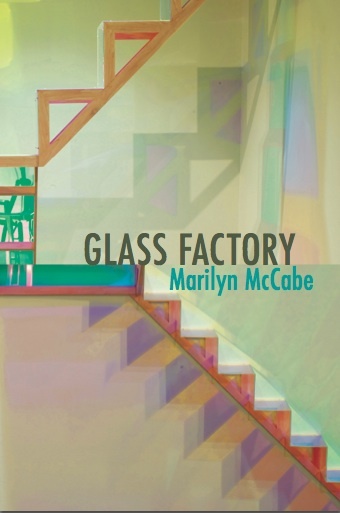

The Word Works, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Two poems in the collection address my recollections of poking around in the history and actual remains of glass factories -- I had an archaeology minor in college, so some of this came about as part of a project in that pursuit. There's something magical about glass -- that it's both solid and liquid, can reflect, refract, and disappear. And the idea of picking through ruins is such a metaphor for the creative process.

I had a number of different ideas for the cover, ranging from trying to find what one photo site called "factory porn" to something abstract involving glass shards, but when I found an image of a sculpture of a glass-like staircase by Victoria Palermo, an acquaintance of mine, I knew I'd found the exact right thing.

Three words: absence, ephemerality, change.

What were you trying to achieve with your collection? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I've lost several contemporaries in the past couple of years, as well as a very young friend, and a very old friend; and my 95-year-old mother broke her leg, requiring us to find her new lodging and a new life situation, which required that I pack up and/or throw away much of the accumulations of her life. Out of this spring-tide of loss, grief, and managing change came these poems.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Poems begin in any number of different ways for me. Often with an image. Sometimes a line. Sometimes I squeeze something out of myself through writing prompts -- e.g., I tell myself to write for ten minutes on "blue" without stopping. If nothing else, it gets my hand moving (my first drafts are always in long hand).

I love the revision/editing process, from beginning to end -- from scrutinizing my own choices to arguing commas and hyphenation with my editor. If a poem doesn't seemed to be realized, I'll say to myself, "Okay, write for ten minutes without stopping in answer to this: 'What I'm really trying to say is...'." I like to turn poems upside down to see if I can learn something new from that perspective. Sometimes I try to rhyme, then unrhyme. It's all play at this stage.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I tend to try to impose some kind of logical order. I have a logical mind, sometimes overly so. Or I try to capture some kind of suggestive narrative arc. With this collection, though, the editor suggested a reordering that moved apart some poems that address similar things or draw from similar kinds of images. By moving them apart a kind of weaving effect was created, with resonances sounding through the collection rather than gathered in single areas. I loved this idea and will keep it in mind in future projects of ordering poems in a collection.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love big ideas. I love poems that start with a small detail and then kapow you with a big idea. I don't know if I do that in my work, but I wish I would.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The collection starts with this poem. It speaks to the emotional core of the collection, the fierceness of loss, but the beauty of life that has such pain in it. I'm also an insomniac, so ... there's that.

I await the night with dread; await the night with longing

With its black strokes, singing,

it smears me, lavish.

I’m the night’s white canvas

turbulent and stiff.

I can grab the burning

stars in my hand.

But I can’t let them loose.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Have you or are you in the process of experiencing loss? Come along with me and look at it lovingly. We can travel together.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I think on the page, often. Poetry meets my natural taciturn tendency and pleases my mind's leap-making desires. I tried to become a fiction writer, but I'm not a natural storyteller. I tried to write essays, but my anxiety about meaning-making led to plodding and uninteresting work. With poetry I can suggest, wonder, be silent, joke, sigh. What scares me most about being a writer is what scares me most about being a human being -- that I'll be too content for too long to stay on the surface of my encounter with the world, that I won't dig deep enough to really think/feel/observe all the wonder. It's fun to be in the midst of inspiration, but, as I said before, I love rolling up my sleeves and editing. Would that I were as fierce with my own work as I am with my long-suffering poet friends. I'm constantly chucking entire stanzas of their work; I may be a little too easy on myself.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I read widely in nonfiction -- science, theology, political history. But whenever I'm stuck for inspiration, I go to art museums. I'm going to be a writer in residence for a week at MassMOCA (the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art) and I'm very excited by that lengthy access to big ideas and the kinds of wacky installations featured there.

What are you working on now?

Taking a hint from Rilke's dingedichte, "thing poems," I'm considering objects and letting poem leap out of them.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I'm loving Lisa Sewell's Impossible Object. And I'm rereading for the umpteenth time Ellen Bryant Voight's Flexible Lyric. I also just got Rebecca Solnit's latest book of essays out of the library. She leaves me breathless.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Yeats's "Second Coming," something from Gluck's Wild Iris, Bob Hicok's "Bars Poetica," Bruce Beasley's "Aphasic Echolalia," and Mary Oliver's "Wild Geese."

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

What's my greatest struggle as a writer? Continuing to make work regardless of the outcome, regardless of rejections, regardless of self-doubt, regardless of the self-limitations I run into or impose, and to make work gladly and with a sense of play. To maintain the sense of play seems vital to me and I often lose it to worry or earnestness or some other terrible intention. To maintain lightness is, ironically, my struggle.

***

Purchase Glass Factory from The Word Works.

Marilyn McCabe’s second full length collection of poems, Glass Factory, was released in spring 2016 from The Word Works. Her poem “On Hearing the Call to Prayer Over the Marcellus Shale on Easter Morning” was awarded A Room of Her Own Foundation’s Orlando Prize, fall 2012, and appeared in the Los Angeles Review. Her book of poetry Perpetual Motion was published by The Word Works in 2012 as the winner of the Hilary Tham Capitol Collection contest. Her work has appeared in literary magazines such as Nimrod, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and Painted Bride Quarterly, French translations and songs on Numero Cinq, and a video-poem on The Continental Review. She blogs about writing and reading at marilynonaroll.wordpress.com.

Marilyn McCabe’s second full length collection of poems, Glass Factory, was released in spring 2016 from The Word Works. Her poem “On Hearing the Call to Prayer Over the Marcellus Shale on Easter Morning” was awarded A Room of Her Own Foundation’s Orlando Prize, fall 2012, and appeared in the Los Angeles Review. Her book of poetry Perpetual Motion was published by The Word Works in 2012 as the winner of the Hilary Tham Capitol Collection contest. Her work has appeared in literary magazines such as Nimrod, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and Painted Bride Quarterly, French translations and songs on Numero Cinq, and a video-poem on The Continental Review. She blogs about writing and reading at marilynonaroll.wordpress.com.

Published on June 01, 2016 06:02

May 24, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Lauren Brazeal

dancing girl press & studio, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

dancing girl press & studio, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…If I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Fatty, succulent, and nipple

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it?

Food is a big thing in my life. I was homeless when I was a teenager, and then lived in group homes where food was closely monitored and I had no say over what I ate. I suppose because of this, themes of “eating” run rampant in my poems, my day-to-day conversations, and even my metaphors. “Consumption”—and its various uses as a verb in our language—is the great unifier of every poem in the book. I'm not sure if it was my goal when I started, but that seems to be the final product.

Zoo for Well-Groomed Eaters exists as a current of savagery running beneath a veneer of civility. Its citizens are mostly outsiders, living in the back alleys of human consciousness; and include scholarly mongrel dogs lecturing on how to handle cats—with interruptions, cockroaches who write thank-you notes to their hosts, animals bred solely for human consumption, and mother rats singing ballads to their starving children. But there's also a great humor to the collection—even if it may be from the gallows. Most of these poems are armed with a wicked smirk.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Most poems in this collection were written while I was earning my MFA at Bennington College. So my writing practice was that of most MFA students: I had monthly deadlines, was required to offer my work for review and workshop, and—as with any workshopping environment—was given either a thumbs up or down regarding my progress. My revision strategy is my own, and involves a more “crockpot” approach—again with the food metaphors. I combine various ingredients, let them sit, and see if the flavor is right after a certain amount of time. This makes me a slow writer for the most part, but I'm usually happy with the result of my efforts.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

My favorite collections are those which invite a multitude of reading approaches—either read front to back, or different pieces at random—with each reading offering its own unique perspective on the text as a whole. I was careful to arrange the pieces in Zoo for Well-Groomed Eaters to function more like movements in a symphony; I feel there's a beginning, middle, and end. But I hope the reader can just as easily pick the book up, select a poem at random, and not feel lost.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

There's a quote from an anonymous child that says. “A poem is an egg with a horse in it." I look for poems that surprise me with their magic. After all, poetry is the grandchild of the magic spell. I look for this as I read, and keep this in mind whenever I write.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read—did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This poem may be my favorite in the collection, so it was easy to choose. I'm a great fan of form, and meter and this epistle began as a petrarchan sonnet that mutated—though it retains plenty of iambic rhythm, and there's a discernable volta. I wrote it for a student reading at Bennington, which are famous for their raucousness. When I return to it now, I still see the Bennington Commons surrounded by snowdrifts; the Commons lounge, with its grand fireplace, filled from corner to corner with maybe 60 less-than-sober MFA candidates. I can hear the hoots and hollers of my friends with each line break. I think the poem embodies that sense of gleeful abandon. I'm not sure if it's the book's heart—I think the book has many hearts, but it's a good example of what a reader will find in Zoo for Well-Groomed Eaters.

Dear Spring,

You're just too spooky

with your ovuleescent

pistils, and your stamens

thrusting powdery

yellow gunk that drives

the bees insane.

You're loud, parading

greenly in the streets

past 2:00am, bottle-

brushing branch tips

labia pink. You stink

of sex and insects,

and you encourage other birds

to bedroom-eye

the trees. Spring, sweetie,

your drag show's bad.

Fuchsia's just

so 1985.

Just look at you in June,

your leggy legs

no longer steady.

Your song was pretty once,

but yaws off-key. Now,

get clean, and clear your craw

for another gobbling

of tits in tassels and

conveniently revealing

boudoir screens.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

“These poems will get you laid.”

What are you working on now?

I've got a full-length manuscript I'm polishing and beginning to submit, which is a series of odd poems, flash-fiction pieces, board games, palimpsests, instruction manuals, and stolen police evidence all telling the story of my time on the streets when I was a teenager. I'm also working on what I thought was a finished third chapbook manuscript, but recently realized—to my excitement—is a portion of a second full-length.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Right now I'm reading the amazingly talented Detroit poet, Francine J. Harris. I love her work so much! I'm also re-reading Megan Martin's beautifully genre-bending debut, Nevers. Chapbooks I've enjoyed recently are Lisa Marie Basile's War/Lock, Thera Webb's Reality Asylum, and Sarah B Boyle's What's Pink & Shiny / What's Dark & Hard.

***

Purchase Zoo for Well-Groomed Eaters from dancing girl press & studio.

Lauren Brazeal teaches writing in the Dallas / Forth Worth metroplex but in her past she's been a homeless gutter punk, a resident of the Amazon jungle, a maid, and a custom aquarium designer. Her second chapbook, Exuviae, is forthcoming from Horse Less Press in 2016 and her individual poems have appeared or are forthcoming in DIAGRAM, Smartish Pace, Verse Daily, Barrelhouse Online, and Painted Bride Quarterly among other journals. Find her online at http://www.laurenbrazeal.com.

Published on May 24, 2016 11:15

May 23, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With ire’ne lara silva

THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I usually have a terrible time choosing titles—for anything, poems, stories, books—but in this case, I knew from the very start. For the first time, the concept for a whole book just jumped into my mind. I’ve always written poems about whatever was most affecting me at that moment. With my first book, furia, I was dealing with grief for my mother’s loss, the confusions of being in my mid-thirties, and attempting to reconcile all the conflicting emotional landscapes. So two months after furia was published, I was wondering what I was going to write about next. And the big light bulb went off and said, this is what you need to do next. Write all the poems you can think of about diabetes and your family and healing—for every vantage point you can think of…as a woman, a daughter, sister, as an indigenous Mexican-American, as a Texan, as a writer and thinker, as a lover, as a patient and consumer, as an active part of my own healing. And Blood Sugar Canto was perfect, with Canto being overwhelmingly important because I believe it is through song that healing happens.

The cover art is a segment of a painting, “When Wind Blows Through Them,” by my brother, Moisés. S. L. Lara. He was inspired by the bead artwork of the Huichol to visualize a spiderweb enduring the wind and reflecting the sun’s light in its coloration. It’s not meant to be a mandala. I’ve been fortunate to have my brother’s artwork on the cover of my first three books as well as on my digital chapbook. In my mind, his art is not only beautiful and unique, it also really speaks to the energy I hope each book conveys.

The three words that come to me: Struggle, Hope, Survival.

What were you trying to achieve with your book/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

What I most wanted to do with this book was to initiate dialogue, between family members, between patients and doctors, between people and their various communities. Also, I wanted to invite the reader to look into some difficult areas internally, in their own psyches and belief systems. Not only how do we share what the physical, emotional, psychological experience of diabetes is like with our loved ones, but how do we talk to ourselves about fear and healing and self-love?

That isn’t to say that this book is only meant for people with diabetes or those who love them. I’ve had some interesting responses from readers who are managing other chronic illnesses or who are grieving the loss of a loved one. The health of our bodies, the strength of our spirits, mortality, and the importance of love in our lives—all of those are themes everyone can identify with.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Writing this collection was very different from any other experience I’d had writing poetry. In some ways, this was more like writing a long story with many, many parts. I wrote the first draft of the collection in a little more than a year. Revising took much longer—another three years of cutting and expanding and refining. I don’t know that I really have a revision strategy. Usually, I’ll just sit with a poem and listen to it, over and over again. Ask myself, are you saying everything you want to say here? Is what it looks like on the page the closest you can get it to how you hear it? Are you pushing as much as you can—are you telling the truest truth?

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

This collection got laid on the floor at least three times. Though I wouldn’t say it was a haphazard arrangement. I arranged and re-arranged them on the floor, trying to decide which section each poem belonged to. Several times, I changed my mind about how many sections the book needed. Close to the end of those three years of revision, I handed my mss to my brother who rearranged the poems in a way that I felt really had a story arc, rhythm and variation, and most of all, really made the whole mss new to me in a way that felt exciting and natural. He said he’d tried to use the spiderweb on the cover to inform the order, weaving the poems into a shape that emphasized their individual strengths and beauty.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I read for what I like to call the heat—for intensity of emotion and language. I don’t care for poetry as an intellectual exercise or as a disembodied eye looking at the world or as a linguistic puzzle with or without a solution. I want poetry that makes me feel, that reminds me I’m alive, that breaks my heart, that fills me with melancholy, that makes me rail at the world. I want language that takes my breath away.

What I love to find in the poems I’m writing is that point at which I lose conscious control of what I am saying or what I think I’m feeling, where I am so taken that I say something that surprises me. I felt that way about the poem, “en trozos/in pieces.” I hadn’t expected a poem about fear to turn into a poem about self-acceptance. That was a huge part of the experience of this collection for me, how often a deeper look at one emotion revealed something entirely different.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

love song for my organs

this is a song i didn’t know

needed singing needed singing

a song for each morning

a song for each night

offered with awareness

offered with gratitude

decades have passed i did not

know your colors your shapes

the work you do have done

or what you needed from me

now i know this song needs singing

i will sing it everywhere i go

i name you now breathe softly

upon you hold you tenderly within

kidneys

you are not forgotten never

you are cherished and i am grateful

i bring you rainwater and riverwater

i bring you flowers tiny blue flowers

i bring you these my two hands filled

with sun light with starlight

i sing you strong sing you whole

This is the first poem I wrote for the healing/”Canto” section of the book. It struck me at a certain point that most people take their health, and the function of their organs for granted. But when you have to learn what they do and how they interact, there is a certain awe for how they work and what they tolerate. It seemed as if a love song filled with gratitude was necessary, and a huge first step in coming to love one’s own body.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a poet means to be willing to be still. To really examine something—a scene, a memory, an emotion, conflicts, complications, history, real or fantastical life. And then to attempt to distill that into language. What scares me and delights me is the same thing—that feeling of having bared too much, told too much, of writing myself into a place where there is no way to hide. Initially, I feel too naked but then I think, perhaps someone somewhere needs to read this. Needs to know they weren’t the only one to feel this way or live through this.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Everything helps. Sometimes I just think it’s about the need to pour language into myself—wherever that language might come from: articles, blogs, poetry, novels, Facebook, books on history or culture—to interact with all of those things.

What are you working on now?

A second collection of short stories, tentatively titled, “Songs from the Burning Woman.” All about grief and sexuality, art and the body, history as we ‘know’ it and history as a living malleable thing. I don’t quite have the language for it yet—re-making, re-visioning, re-creating are not quite the words I want. I’m a many-generation'd Mexican American who identifies primarily with my Native American roots. While Indigenous people have survived the last five hundred years, the wounds of historical and current violence, disease and poverty, decimation and assimilation, are ongoing. I think these stories have to do with art and healing and love as a counter to all of those wounds.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I’ve been reading a lot of manuscripts in progress. Two that I’d recommend that will be released soon are poet Joe Jimenez’ first YA novel, titled Bloodline (Piñata Books), a new versioning of "Hamlet" where the main character is a 17 year old Chicano in current-day San Antonio….and With the River on Our Faces, the second collection of poetry from Emmy Perez due out this fall from University of Arizona Press.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

I can tell you not just which poets/writers, but which exact quotes:

First, not a poet, but a philosopher, and this one is actually on my list to be one of my first tattoos: “Fire rests by changing.”—Heraclitus

Second,

“amanecete mundo

entre mis brazos

que el peso de tu ternura

me despierte” –Francisco X. Alarcon

Roughly translated, “greet the dawn, world/ in my arms/ may the weight of your tenderness/ awaken me”

Third,

“I am afraid to won a Body--

I am afraid to own a Soul--

Profound-precarious Property—“

—Emily Dickinson

Fourth,

“My old furniture is rotting in the barn where I left it, and I myself, yes, my God, I have no roof over me, and it is raining into my eyes.”

–Rainer Maria Rilke

Fifth,

“Mientras yo estoy dormido/Sueño que vamos los dos muy juntos/A un cielo azul./Pero cuando despierto/El cielo es rojo, me faltas tú.”

—Jose Alfredo Jimenez

Roughly translated, “While I’m sleeping, I dream the two of us on our way to a blue sky. But when I awaken, the sky is red, and I don’t have you.”

***

Purchase Blood Sugar Canto.

ire’ne lara silva is the author of furia (poetry, Mouthfeel Press, 2010) which received an Honorable Mention for the 2011 International Latino Book Award and flesh to bone (short stories, Aunt Lute Books, 2013) which won the 2013 Premio Aztlan. Her most recent collection of poetry, blood sugar canto, was published by Saddle Road Press in January 2016. ire’ne is the recipient of the 2014 Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Award, the Fiction Finalist for AROHO’s 2013 Gift of Freedom Award, and the 2008 recipient of the Gloria Anzaldua Milagro Award. Visit www. irenelarasilva.wordpress.com.

Saddle Road Press: http://saddleroadpress.com/blood-sugar-canto.html

Published on May 23, 2016 06:26

May 17, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Bernard Grant

Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?The book is titled for the last essay. “Puzzle Pieces” is composed of small scenes which are, for the most part, arranged in reverse chronicological order, and is tied together by the recurring image of a woman who pieces a puzzle in front of a window.

Titles are difficult for me, but as I wrote this piece—as I refined the scenes, printed them out, cut them up, and arranged them on the floor until the essay felt right—“Puzzle Pieces” became an obvious choice.

After I completed the manuscript, I felt I’d created a larger version of that essay. Where in that piece short scenes create a bigger picture, the chapbook is composed of short essays that, like puzzle pieces, fit together to create an image, as an experience, in the reader’s mind.

Choosing the right cover image wasn’t as easy as choosing a title. It wasn’t easy at all. But it was just as fun. I contacted a friend, a writer and visual artist, whose work I admire. Clare Johnson read the manuscript a couple of times and met me in a Seattle café with her laptop. We spent two hours looking through images and discussing the essays. She’s a terrific artist and many of her illustrations made great possibilities. There were so many prospects. But I lost interest in all of them once I saw the image I finally chose. I looked at a few more after I saw it, but I’d already made the decision. I liked, among many other things, the way the houses fit together to create a community.

Three words to sum up the chapbook: small, spare, subversive.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Creating this chapbook was an act of curiosity: I wanted to see if I could create a longer narrative out of some short essays I’d written. I wondered what story they would tell once I placed them together, given the proper structure.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Puzzle Pieces, unlike the full-length fiction manuscript I’m working on now, was assembled from previously-written essays. So my “writing” process for this collection was mostly an act of arrangement. Once I had everything in place, I began to revise, tightening the language and, in some cases, rewriting scenes and changing titles.

I don’t have a specific revision strategy for anything. Maybe I haven’t been writing long enough, or, perhaps, it’s that everything I write—from flash to longer short prose pieces, stories and essays—feels so different, I don’t approach anything the same way. When writing a flash piece, I tend to write it in one sitting, tinker with it a bit, then put it away for a while, try to forget about it, while I draft or revise something else.

Many of these essays took several months to write. I needed time between drafts to figure out what the hell I was writing but I also struggled to find the proper structure and point-of-view for each piece (most are in first person but a couple are in second). One piece was written very quickly, from a Moleskin notebook to MS Word with very few edits. Another piece of similar length took a nearly a year to write, with countless revisions.

How did you order the pieces in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your them or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Chronologically. Ordering them chronologically allowed the themes to emerge in a way I could understand. The chapbook shrank as a result. I cut a couple of pieces when I began to see the essays as a progression from a narrator who destroys his body to someone who is surrounded by broken bodies to someone who lives with a broken body. I was pleasantly surprised by the other connections that began to emerge once I settled on this structure.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this particular piece for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last piece you wrote for the book?

As much as it shows my once-obsession with the em dash:

“The man who walks like I did just two months ago—normal gait, normal speed—hurries into the elevator, a smile on his face. He says hello, points to number two, hesitates—as I do, too—presses it, and stands quietly, grinning, until a ding announces our destination.”

This passage comes from the essay “Puzzle Pieces”, which takes place in a physical therapy ward. I like how this paragraph sounds, but I also like what it said to me: we’re in this together. Whatever this is. When I put it into the chapbook, however, the essay, particularly the last line, seemed less about the struggles I shared with other physical therapy patients and more about the struggles I share with every human in existence. Life, like a physical ailment, is harder for some than others, but we all end up in the same place and we all struggle in the meantime. Why not smile? Why not say hello?

For you, what is it to be a writer? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a writer—for me—is to be an artist who is thrilled by the interplay of words, people, life, and sound.

What scares me most about writing is the uncertainty, those questions I ask myself as I write. Will anyone publish this? Do I want someone to publish this? Do I want someone to read this? Who would read this? Who would like it? Would I read this? Will I finish it? Will I like it?

What’s most gratifying about writing is that it helps me to better understand the books I like to read. It’s also energizing to live in the middle of a narrative, when a story or essay is taking shape—when I’m recognizing and exploring thematic connections, rearranging paragraphs, perfecting sentences, etcetera—even when I’m away from my writing desk.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write?

The Synonym Finder by J.I. Rondale

What are you working on now?

I’m writing a collection of interlinked stories that examines the interactions between emerging and middle-aged adults and captures the interconnectedness of a small city, Olympia, Washington, which is where I lived when I started writing them. The stories are centered around a mixed-race family but the collection moves beyond them and into the community. The more I write, the more I revise, the more the stories begin to resemble chapters, with the book taking the shape of a novel.

I’ve also completed a chapbook-length collection of interlinked flash fiction stories.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Leah Stewart’s latest novel The New Neighbor indulges my fascination with the weaving of multiple perspectives and multiple stories in a single narrative. It isn’t a linked collection (Olive Kitteridge; In Our Time, Winesburg, Ohio) which is my preferred genre, but with its short chapters, and multiple points of view and storylines—there’s also a story within a story—it certainly has that story cycle feel. It’ll hook you.

***

Purchase Puzzle Pieces.

Bernard Grant has been awarded a 2015 Jack Straw Fellowship and a June Dodge Fellowship. His nonfiction has been nominated for The Best of the Net Anthology and his fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Chicago Tribune and Crab Orchard Review. He is the author of the nonfiction chapbook Puzzle Pieces (Paper Nautilus Press, 2016) and he serves as the associate essays editor at The Nervous Breakdown. Find him online at www.bernardgrant.com.

Bernard Grant has been awarded a 2015 Jack Straw Fellowship and a June Dodge Fellowship. His nonfiction has been nominated for The Best of the Net Anthology and his fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Chicago Tribune and Crab Orchard Review. He is the author of the nonfiction chapbook Puzzle Pieces (Paper Nautilus Press, 2016) and he serves as the associate essays editor at The Nervous Breakdown. Find him online at www.bernardgrant.com.

Published on May 17, 2016 04:41

May 11, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Lynn Pedersen

Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The press designed the cover for me and I had input on the image. Carnegie Mellon was very accommodating because when I say I had input, I described the botanical print theme that I wanted down to the insects that could/couldn’t be included. I said yes to snakes, lizards, beetles and moths, but no ladybugs, dragonflies or butterflies. The book has a strong survival/extinction theme to it, and I did not want the cover image to be too cute—more “eat or be eaten.” The print is from the Getty Museum.

The title was inspired by Linnaeus and his work with taxonomy. I wrote the science-themed grief poems first, poems that contained astronomy metaphors, telescopes, the vastness of space, and later I wondered about small things—microscopes and Robert Hooke’s work and tiny organisms and cells and objects we can't see.

Three words to describe the book: science, grief, pattern. If I could add three more they would be: fossil, extinction, endure.

What were you trying to achieve with your collection? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

In the early stages, I didn't have a master plan for the book. I was interested in the patterns of grief I recognized during years of fertility issues, and I felt compelled to try to express those experiences—though there isn’t a good vocabulary for grief in today’s English language.

The controlling hypothesis or goal—if I can call it that—was to see if the language of science can be used as a filter for grief. Many people and voices inhabit this book—Charles Darwin, Alexander Wilson, Robert Hooke, naturalist George Shaw, J.M.W. Turner. Geologic time in the book moves from the Precambrian to the Anthropocene. I’d describe the world of the book as rich and historical, exploring individual narrative against a larger backdrop of science and society.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I function like a hunter-gatherer in my writing practice. I spend months reading and researching, absorbing and digesting, and eventually there is a cross-pollination of ideas and images that start to form. The collection has a variety of first, second, and third person poems, and three interwoven narrative threads—grief, Darwin/evolution, and nomenclature. The first person narrative poems were written first, with the science poems coming in along the way, primarily toward the end of the process.

For revision, I like to leave poems in a state of development for as long as possible. The point at which I start to finalize line breaks, images, logic and word choice is maybe a week before I am thinking of sending the poem out. At that point, it has “settled” enough that I feel comfortable with it.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

The arrangement of this collection was planned to the extreme. It had to be, though. Placement is essential in this book because the poems deal with grief, and the experience for the reader needs to be considered. It’s not helpful to hit a reader right off with eight intense grief poems in a row. The poems alternate between three narrative threads, and also move from very grounded and personal narrative poems to more abstract lyric reflections.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I am always waiting with anticipation for the instant when the poem I’m reading (through its language or its imagery or some mechanism) creates “lift,” similar to an airplane travelling down a runway and then lifting off the ground. Something has to surprise me or change the way I view language when I read a poem. I’d like to think at least a few of my poems might have this effect on others, but it’s hard to consciously insert this quality into a poem. It grows out of craft and—mainly—my intense engagement with what I am writing. Somehow if I write well enough that “lift” will be there.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The Infinite Density of Grief

What no one tells you is grief

has properties: expands like a gas

to fill space and time—the four corners

of your room, the calendar

with its boxed days--

and when you think it can’t claim anything more,

collapses in on itself, a dying star,

compacting until not even a thimble

of light escapes.

Then grief sleeps, becomes

the pebble in your shoe you can almost

ignore, until a penny on a sidewalk,

dew on a leaf—

some equation detailing the relationship

between loss and minutiae

sets the whole in motion again—

your unborn child, folded and folded

into a question, or the notes

you passed in grade school

with their riddles—

What kind of room

has no windows or doors?

This poem is the first in the collection. It was written after a visit to the Rose Center for Earth and Space, part of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. As I learned about the concept of infinite density, I made a connection that the language in the museum wasn’t just talking about the universe, it also described the grief that I had been unable to express regarding pregnancy loss. The poem explores the properties of grief, its all-encompassing nature and its ability to return at the oddest times, triggered by the smallest things.

The poem is significant because it sets up the way science will weave throughout the book—science language giving voice to grief and loss, science fact balanced with narrative detail. I think of “The Infinite Density of Grief” as a cornerstone poem within the architecture of the book.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

If you’ve ever lost anything or anyone and did not feel that you had a vocabulary to describe that loss, this book might be a starting point.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

Poetry for me is an experience of language (and time) and the practice of a very intense meditative focus, and writing is also pattern and problem solving. What scares/thrills me is what I will find out by writing the work, and where that voice will take me. The flip side of the unknown is each poem teaches me something new. Generally that’s a good thing. The best times are when I’ve worked out something that hasn’t worked, seen a new way to do things, and the times when I’m writing and everything is flowing.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I read a lot of things other than poetry, but the sources that come back and work their way into my poems are usually science, natural history, and biography—nonfiction books. Reference books and maps are a rich source of words and images, too, and I like the personal voice of diaries, journals, and letters. Many of my poems are a response to my reading.

What are you working on now?

I have drafts and manuscripts in progress, and I’m separating out what will become poems and what will become essays or plays or some other form. Science is still a huge obsession, and I expect future collections to reflect that. I’ve also started to do a lot of reading related to the environment. It will be interesting to see how that information comes into play.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Lucia Perillo’s Inseminating the Elephant. Perillo has a wildlife management background and her love of science is reflected in her poetry. Selected poems of Francis Ponge. Rose Metal Press’s Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction. I am drawn to prose and more experimental forms of writing, even when I don’t write in that form myself.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Darwin (not a poet but his writing has a lyric quality), Shakespeare, Walt Whitman, Dickinson, Katherine Philips (“What on Earth deserves our trust?”), Frank O’Hara, Wislawa Szymborska, Miroslav Holub. That’s more than five but I don’t know who I would cut out.

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Q: Do you have a particular place that inspires you to write?

A: I do really well in museums—science, natural history, or art—or also in theaters before a performance. Something about the stage and open space and darkness, and smell of paint and wood, opens up possibilities for me. Unfortunately, it's not always convenient to travel to a specific building to write. Most of the time, I write at home.

***

Purchase The Nomenclature of Small Things from the University Press of New England.

Lynn Pedersen is the author of The Nomenclature of Small Things (Carnegie Mellon University Press Poetry Series), Theories of Rain (Main Street Rag’s Editor’s Choice Chapbook Series), and Tiktaalik, Adieu (Finishing Line Press New Women’s Voices Chapbook Series). Her poems, essays, and reviews have appeared in New England Review, Ecotone, Southern Poetry Review, Slipstream, Borderlands, Poet Lore, and Heron Tree. She is a Pushcart Prize and Georgia Author of the Year Award nominee. She is a playwright and member of the Dramatists Guild of America. A graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts, she lives in Atlanta, GA. Find her online at www.lynnpedersen.com.

Lynn Pedersen is the author of The Nomenclature of Small Things (Carnegie Mellon University Press Poetry Series), Theories of Rain (Main Street Rag’s Editor’s Choice Chapbook Series), and Tiktaalik, Adieu (Finishing Line Press New Women’s Voices Chapbook Series). Her poems, essays, and reviews have appeared in New England Review, Ecotone, Southern Poetry Review, Slipstream, Borderlands, Poet Lore, and Heron Tree. She is a Pushcart Prize and Georgia Author of the Year Award nominee. She is a playwright and member of the Dramatists Guild of America. A graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts, she lives in Atlanta, GA. Find her online at www.lynnpedersen.com.

Published on May 11, 2016 07:56

May 3, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Leigh Anne Hornfeldt

Winged City Chapbooks, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Winged City Chapbooks, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The title popped into my mind one day as I was trying to describe the latest project I was working on to someone. I kept using the word fleshed when talking about the poems: I wanted to flesh them out from something internalized to something almost tangible. While in the middle of talking it hit me that was the perfect title for a book that deals with themes of mental illness and how that manifests in our actions and our flesh. Some of the poems have a dark humor, some are weird. I felt like the image of the skeleton bride was fitting in that it plays with the idea of being naked, without flesh. It all just ties in nicely, at least in my mind! I’d say this book has a sense a vulnerability, a sense of humor, and a sense of urgency.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

A lot of these poems were born out of a daily writing challenge I was part of. As I wrote I started to see themes manifest, especially the idea of mania versus depression that I experience. A lot of this book also deals with the ways in which we change over time, mentally and physically. I wanted this book to play upon the tensions of those differences.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I like to begin by handwriting a quick draft, kind of like a runner might stretch before going for a run. After I have the basic idea, I let it brew for the morning. I generally sit down at my laptop in the afternoon and write the real poem. I let that rest and then revise after a few days have passed. It’s pretty methodical but also I think I need that break time so that surprises can still happen. Sometimes a line will pop into my head or I will see something that has to go into one of my poems. They need room to breathe and become their own thing.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I am a floor organizer! Usually I can pick the first and last poem pretty easily. Then I take to the floor and try to see which poems speak to one another. Sometimes it’s just an image or a single word, but once I see the relationships between the poems it feels natural.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

Like I said before, surprise. Sometimes I wish I could be more spontaneous when writing. I admire poets who are able to relax and let what happens happen.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This is the last poem of the book. It’s dark but funny like some of the other poems. It was one that was a lot of fun to write so I hope it’s also fun to read.

This Is Not a Drill

According to a dot on a map

WE ARE HERE. Purple-faced and panting,

no doorknobs to twist or keyholes

to slip through. Nothing works, especially

not our mouths. Everything

is black ice & sugar sapphires. A crow

watches the frenzy, enrapt. Please

don’t forget to panic. Stow

your baggage. Secure

your own mask before helping the person next

to you. Do you have insurance?

You should. This is not an extravagance.

There are rubber gloves

in all the drawers but none

your size. The following time zones

are on a two-hour delay. We’ll all stay

in these bodies until further notice.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Hey, wanna know what it’s like for me to be bipolar?!

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a poet is to be aware. I probably stole that from someone but I believe it. It requires constant attention. What scares me the most is probably the vulnerability in that. Sometimes I want to look away from things that are upsetting but they’re poem material. The newest collection I’m working on deals with disturbing headlines from newspapers and online articles. The working title is Rattled. It’s been tough. What gives me the most pleasure is finishing the poem. That last little revision and then you know you’ve got it. That’s the best feeling, the most satisfying to me.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Not sure I could list five, but this is funny because I have a couple of lines from Sylvia Plath’s “Kindness” on my forearm: ‘The blood jet is poetry, / There is no stopping it.’ I got that as a reminder. My grandmother is a poet and she is where I got my love of writing and I wanted to always be able to look down and remember that what she loves is in me always.

***

Purchase Fleshed from Winged City Chapbooks.

Leigh Anne Hornfeldt, the editor for Two of Cups Press, is the author of the chapbooks East Main Aviary, The Intimacy Archive, & Fleshed. She is the recipient of a grant from the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Her poem “Laika” placed 2nd in the Argos Prize competition and in 2012 she received the Kudzu Prize in Poetry. Her work has appeared in journals such as Spry, Lunch Ticket, Foundling Review, and The Journal of Kentucky Studies. Find her online at leighannehornfeldt.com or

Leigh Anne Hornfeldt, the editor for Two of Cups Press, is the author of the chapbooks East Main Aviary, The Intimacy Archive, & Fleshed. She is the recipient of a grant from the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Her poem “Laika” placed 2nd in the Argos Prize competition and in 2012 she received the Kudzu Prize in Poetry. Her work has appeared in journals such as Spry, Lunch Ticket, Foundling Review, and The Journal of Kentucky Studies. Find her online at leighannehornfeldt.com ortwoofcupspress.com.

Published on May 03, 2016 07:25

April 26, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Victoria Looseleaf

Isn't It Rich? A Novella in Verse, Gordon Grundy Publishers, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Isn't It Rich? A Novella in Verse, Gordon Grundy Publishers, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I must admit that I grappled with the title – and titles generally come easy to me. For instance, my second novel, Whorehouse of the Mind: A Novel of Sex, Drugs and the Space Program, seemed like a no-brainer, although writer Richard Meltzer thought that I “appropriated” it from Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind. I use the royal ‘we’ in my blog writing and Facebooking, so I came up with Our Beautiful Life. My publisher, the wonderful Gordy Grundy, said I should translate it into French, as we both think there are too many poseurs in L.A., so it became Notre Belle Vie for a while. I also thought about JAG: Jewish American Goddess, Being Cate Blanchett, What’s In It For Me, Dear C**T, Brainwreck and Screwtopia. "Screwtopia" actually ended up being the name of one of the book’s poems. Then there were the organic titles derived from the book’s poems, such as Juliet On the Prowl and An American Reverie. Finally, I am a huge Stephen Sondheim fan, and was perusing one of his books, Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes, and there it was – Isn’t It Rich, from "Send In the Clowns." I also used to play that gorgeous and enigmatic song on the harp at funerals and brisses, so this title had it all for me.

At the same time – while writing the poems and thinking of a title for the book, I was asking artist friends of mine if they would send me some images I could consider for the cover. For that, I was also asked to send these people several poems. The artist, Lita Albuquerque, loved the poems I sent and read them to her daughter, the choreographer/dancer, Jasmine Albuquerque Croissant. She immediately recommended the terrifically talented well-known Belgian artist, Katrien De Blauwer, whom Jas knew through her husband, Rodrigo Amarante. When Katrien agreed to supply the cover image, my publisher and I were overjoyed.

Three words to describe my book would be: Vivid, erotic and deeply disturbing. Seriously, I know we like to use the journalistic three, but I would also have to add, intoxicating and hilariously funny. Not to mention, profoundly human and occasionally surreal.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I didn’t set out to “achieve” anything, except to write an authentic account of a life lived to its fullest, based on memories – sometimes incredibly detailed, sometimes foggy, often conjured. A free spirit lives in this book, someone, however, with whom I am quite familiar. In fact, I would have to say that we have a love/hate relationship. I also subtitled it, A Novella In Verse, because I feel that each of the poems is its own, self-contained story. There is a definite thread, a through-line, which some people have said is more along the lines of sex, drugs and travel. All I know is that this person has had quite a life. Perhaps I should have called it a memoir-in-verse, but that might have been too leading. In any case, by subtitling it a novella, I figured Hollywood might want to option it – and I would be more than happy to see a Cate Blanchett or Rooney Mara take a stab, with Julia Roberts in middle-aged and then the fabulous Meryl Streep looking back on it all with wisdom, wit and wonderment.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Since I am a freelance arts journalist who has interviewed thousands of people and is on constant deadlines (I have written more than 500 stories/reviews for the L.A. Times, I’ve interviewed hundreds of artists of all stripes for KUSC radio, and have also written program notes for the L.A. Philharmonic as well as the L.A. Master Chorale, introducing audiences to world premiere by such luminaries as Steve Reich, Billy Childs and the Matrix composer, Don Davis…and the list goes on), to put it bluntly, I write quickly. I have also re-invented myself – from professional harpist to print and broadcast journalist, finally, going digital and writing for online publications, as well as my own blog, The Looseleaf Report. That said, this book came about almost as a fluke. I was invited to a “Pasta and Poetry” party last June, so I figured I would bring a poem to read. I had been keeping notebooks (after all, I hail from the Looseleaf clan), for years, and, perusing several from a certain time period, saw the germ of something, which then became, Smile. There were all sorts of intellectuals, architects, artists, writers, et al at this party – many of whom were reading poetry aloud by famous poets. I was feeling a tad insecure and thought, perhaps, that I shouldn’t read. But I mustered my courage, read, and, in a word, killed. Then, a week or two later, my friend, Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Kate Johnson, asked me to play the harp at a big art event she was curating at Santa Monica’s Bergamot Station in July. I reminded her that I didn’t play professionally anymore – I had actually abandoned my station wagon years ago – but that I could do spoken word. Kate quickly agreed.

I then wrote about nine or 10 poems (like choreographer, Agnes DeMille, when she was asked by the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo if she had an “American” piece of choreography the troupe could use for its U.S. debut, she said, “Of course,” then went home and made the work that became Rodeo. And, no, I am not comparing myself to DeMille, but, as I said – and to my point – I work quickly).