Nicole Rollender's Blog, page 6

February 8, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Weslea Sidon

Published by Rain Chain Press, 2014 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Published by Rain Chain Press, 2014 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The title is from one of the poems. I think many poets, good writers in general, are holy fools, able to take the most difficult realities (love, loss, frustration, regret, anger, despair, joy, etc.) and live with them in their raw state long enough to observe and document, without losing the depth of feeling. The fool in literature is a word twister, disguising truth as humor, working the dangerous space between what one wants to know and what one needs to know.

Let me say, though, that I am not there yet. Holy fool is a goal, not a description of me.

The image is a photo by my husband, Curtis Wells. His photographs often capture the moment when a commonplace image inspires questions about how we think about what we see.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

The poems in this book were written over a long time, through many challenges. I hoped that they had enough universality to give a reader a sense that we are all in this together.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Since the poems were created over many years, the process changed. Some years there was lots of time to work on poetry, some years very little. I sit and write at the computer (used to be typewriter). I stopped writing in longhand when I learned to type. Junior high, 1950-something. The speed of the typewriter was thrilling, and so is the computer. I spew, then revise ad nauseam. Revision is the real work. I have peers who help weed out the sloppy, sentimental or pompous stuff, and I try to channel them when I start revising.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Putting a manuscript together, choosing the poems, ordering them was so stressful it sent me back into therapy. Some days I threw all of them (hundreds) on the floor and made up some weird test like choosing what fell together, or choosing all the ones that fell face up, or face down. Slowly, I gave in to the reality that there were themes and objectives, that many were just not ready, that some were better than others, and became able to make choices that made sense, for better or worse. There is a vague chronology in it.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

A reason for it to be. A thought I haven’t thought. A surprise, or a warmth that makes me feel I belong in the world.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This is the first poem in the book. I wrote it years ago, but it has been republished a couple of times and people seem to like it.

I Keep Losing Things

I keep losing things

car keys, hats, paper cups

places on the page

I keep losing the sense of purpose

that propels me to the ends of sentences

I have lost the state of grace that comes

to those who know the plumber's number

or the limits of anticipation

I keep finding things that look like

reasons to continue looking

details masquerading as philosophy

I remember that these make a lie

but forget how many times

I've learned the lesson

This is also from the first section:

Jamaica Bay, 1953

1.

Our road had not yet

given up its secret.

We could drive away

from the new six-story boxes

that grew in empty lots

where once only shorebirds lived,

and old cars died

away from the river

to the creek

where shanties held

damp mysteries in patchwork shingles

we could sit beside the speckled dunes

and wait for the murmuring tide.

2.

We let our fingers drag behind the rowboat

swirling slips of marsh grass

trying to spell our names.

Our names washing out to sea,

and soon the smiles of our young parents

erased by hospitals and surgeons.

But not quite yet, there is, for now

the sunlit island so small our jumpings

make it bounce--and we are jumping

loping side-wise after horseshoe crabs

tossing bits of crusty sandwich to the gulls.

3.

I float beneath the cloudless ancient sky

seaweed woven to a wreath around each wrist.

My eyelids droop and close, I have no fear

of water, nor of solitude.

I have yet to learn how small I am

how little I can do.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

“Do me a favor, read this.”

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

It is hard work. I am driven to write, always have been. I have turned my back on it many times, only to find I was more miserable not doing it than doing it. I have had to learn that I write for me, that I am never going to be a great poet, but I can live with being pretty good. Some people like my work; they tell me it speaks to them, and that is a help.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I read nonstop most of childhood. I loved reading the dictionary, the encyclopedia, anything that I could get away with that kept me from homework. I love the dictionary; it is my favorite tool. Often when a word is not right, but I can’t find another, so I go to the dictionary to find all the secondary meanings and etymology. That sometimes leads me to the meaning that the wrong word was looking for, and I can find the right word.

What are you working on now?

Poems, very slowly, about whatever comes up at the moment I am writing. I don’t have much time, so there is only process now, with no intention of doing anything with it.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I read junk to relax. Well-written junk, like good mysteries, but nothing to inspire anything—unless I go through with a plan to commit the perfect murder on some of my poems.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Whitman, Dickenson, e.e. cummings, Rexroth, Li Po

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Q: How do you keep going?

A: I don’t know.

***

Purchase The Fool Sings from Rain Chain Press.

Weslea Sidon is a poet and musician who lives in Seal Cove, Maine, with her husband, cats, and big plans to finish the garden. Her poems and prose have appeared in many literary magazines, a few anthologies and a few newspapers. Weslea teaches guitar, and has taught poetry and creative writing to children age 10-16 at Summer Festival of the Arts since 1989. She was awarded the Martin Dibner Fellowship in Poetry in 2002. The Fool Sings, her first full-length book, was released by Rain Chain Press on July 1, 2014.

Weslea Sidon is a poet and musician who lives in Seal Cove, Maine, with her husband, cats, and big plans to finish the garden. Her poems and prose have appeared in many literary magazines, a few anthologies and a few newspapers. Weslea teaches guitar, and has taught poetry and creative writing to children age 10-16 at Summer Festival of the Arts since 1989. She was awarded the Martin Dibner Fellowship in Poetry in 2002. The Fool Sings, her first full-length book, was released by Rain Chain Press on July 1, 2014.

Published on February 08, 2016 04:58

February 1, 2016

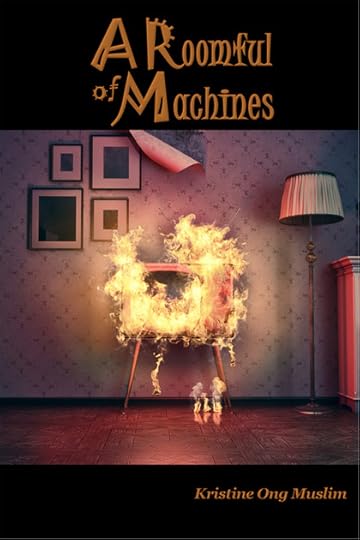

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Larry Eby

ELJ Publications THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

ELJ Publications THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The title Machinist in the Snow was part of a small chapbook project with a friend of mine, Aaron Reeder. I’m not exactly sure where it came from, but usually I come up with the titles of projects first, then I try to figure out what they are about. This just sounded right at the time. Aaron and I went to school together at Cal State, San Bernardino, and one summer we decided we wanted to put together a collaborative chapbook. So we decided to come up with two different project titles, write 10 poems to each, and put them together to see how they melded. His was Bathing in Antlers, so there was definitely an eco-theme going on. I think, ultimately, my title came from my obsession with how the industrial complex interacts with the world.

The cover art is by an artist named Justin Witmer, who I also met during my time at Cal State, San Bernardino. He had posted some recent album covers that he had done for some death metal bands, and the art really matched up with what I was going for. It’s dark, surreal, and sparse, feelings that relate to the book’s content.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Although I didn’t have a goal starting out, I think the book eventually revealed its goals during the process of writing it. Poetry is an act of unification. It seizes whatever it can and combines it, revealing something new. I think this project attempts at reconciling the two major forces of human activity and nature’s push to sustain itself. I don’t necessarily think this is a binary, since human activity is, in a sense, natural, but there seems to be a generally accepted idea that it is somehow separate.

I’m not sure I could claim the title of epic, but the book is a long poem with one narrative arc. In it, a machinist self-exiles into a frozen, wasteland. He’s mostly observer in the beginning, but becomes entwined in it, learning as the narrative progresses that he is there to restore it. It is, in a sense, a hero’s journey. Structurally, there are a lot of commonalities. This wasn’t necessarily the goal, but it’s definitely something I’m interested in, so I’m not surprised it ended up in the book.

The machinist is this sort of pseudo-tech, old world blend of historical innovation and modern innovation. He’s, ultimately, outside of any era. Once he passes the threshold into the world, he’s no longer in any specific time, but all of them at once. So the language attempts to mirror that. There’s a lot of cogs and computer language. There’s a lot of memory of a world that may or may not have existed yet.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I wrote this book fairly quickly over the course of a couple months. I’m all for the quick draft, since once you have an idea, it’s important to keep the tone of that idea similar. Because of technology and social media, our vocabularies change rapidly and this can mess with consistency. Something I may write today, I wouldn’t dare write the next, so I try to get everything down while I’m in that mode.

Editing is a bit different. I try not to tweak too much of what comes out the first time around. But I did end up rewriting this book (mostly copying from one document to the other) in one afternoon to make sure there weren’t any moments that didn’t match the overall feel. There was a lot of rewriting and structure changes. Originally, the book had quite a lot of formal forms in it. I only kept two of the formal structures during that rewrite. There is a villanelle, that is slightly modified, and a perfect haiku hidden in the middle of a free verse poem. There used to be a formal pantoum, but now it’s only a fragment of what it used to be.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Since this is a narrative poem, it took a lot of rearranging for me to actually find what that narrative was. I wrote it in fragments and it used to be ordered by numbered sections. But once I started to see that there was a narrative, I had to find a way to rearrange it. I tried my old process of taping everything to a wall and rearranging it, but it didn’t quite work out. I ended up using 3x5 cards with the first and last lines of the sections, and a note about where the machinist was physically in the poem. Was he in the forest? On the highway? Leaving home? In a cave? And so on. Once I had that organized, it was a little easier to see how he traversed through the story.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I’m a sucker for deep image. But at the same time, I want the poems to sound good. I love language that has a musical flow to it. Not rhyme, although there are a few hard rhymes in the book, but a smooth rhythm that is underneath the surface of it. I also love poems that play with how they look on the page. To me, it’s about variance. If you can give variance to the poem’s visual form, it keeps the reader attentive. At least, that works for me in poems by others.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

I will awaken again to the sounds of my body

scrambling through a frozen clearing.

Floodplain. Snowstorm. I dig

as a variance of light

through to the heat beneath. Me as

system of trees, me as river delta. I will

awake again to the sounds of my body

to train the season

and make a cog out of my lungs. Spring

will bloom atop a droughted

floodplain. Snowstorm. I dig

the treasury of seeds,

bloom and the world whirls

around its stem of wings. I will

awake again to the sounds of my body.

If traveler, then risk.

If decay, then begin to sink

again into what I have named our caravan:

Floodplain. Snowstorm. This digging

in the frozen sea

to find myself—that is to say: I will join

the soil again as the hands of the universe.

I will awaken again to the sounds of my body.

to the sounds of my body,

floodplain, snowstorm. I dig and bury.

This section is at an important part of the book, right after the machinist realizes his path. There are many “restarts” in the book, and this follows one of them. It’s also the villanelle I had mentioned above, and shows a little bit of the formal aspects.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Want to visit my insanity?

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To me, being a poet is part of the constant grinding against the universe. It’s a record of how we interpret reality. I think a person becomes a poet because they feel like they barely understand what is happening around them. It’s my way of discovering how I view the world and, in that sense, it’s a process of creating the world. Reality is perception, and poetry is the process of both creating perception and being observant. It’s a circular motion. Viewing, interpreting, viewing askew.

What scares me the most about that process is that it exposes the void underneath any foundation I’ve created.

What makes this pleasurable is that there is always room to discover something in that void. The void of our perception is much like the structure of space: mostly empty, except a few specs of actual matter. That is the ground I’m looking for. It’s rare, nearly non-existent on the scales of the universe.

What are you working on now?

Currently, I’m working on editing a manuscript called The Weather Here, which is a prose poetry/flash fiction manuscript. It is a range of stories about weather. To me, weather isn’t just the physical weather, but also the way our rumors move, the way crime spreads, and the turbulence between relationships. It’s the legends we keep and our living spaces.

I’m also slowly editing another manuscript based on the moons of Jupiter called Radio Jupiter. It uses the moons as a lens to look at American culture. The problem I’m having with this manuscript is that the moons keep being discovered and renamed. So who knows when it will be done.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

There’s a few that I read recently and really connected with. Sandy Longhorn’s The Alchemy of My Mortal Form is a great read. As well as Anthony McCann’s Thing Music. Oh, I have a must read: Madness, Rack, and Honey by Mary Ruefle is a fantastic collection of lectures that was suggested to me by poet Jessica Morey-Collins. It really got me out of a writing funk this last summer.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Tracy K. Smith

Tomas Tranströmer

Ezra Pound

Traci Brimhall

Julie Sophia Paegle

***

Purchase Machinist in the Snow from ELJ Publications.

Larry Eby is the author of two books of poetry, Flight of August, winner of the 2014 Louise Bogan Award from Trio House Press, and Machinist in the Snow, ELJ Publications 2015. His work can be found in Forklift, Passages North, Fourteen Hills, Thrush Poetry Journal, and others. He is the editor in chief of Orange Monkey Publishing, a poetry press in California. Find him online at www.larryeby.com.

Published on February 01, 2016 03:53

January 26, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Lesléa Newman

Headmistress Press, 2015 Let’s start with the book’s title, I Carry My Mother, and your cover--a painted image of a pair of red pumps. How did you choose each?

Headmistress Press, 2015 Let’s start with the book’s title, I Carry My Mother, and your cover--a painted image of a pair of red pumps. How did you choose each? The title comes from the last poem in the book, a rhyming pantoum which expresses all the ways I carry my mother in my body (I physically resemble her in many ways) and heart. “I Carry My Mother” is what the book is about: how I carry her with me now that she is gone. The cover image was chosen by my publisher. Both my mother and I love shoes. She had lovely, delicate size 6 ½ feet with elegant high arches. Alas, I have large, flat, wide peasant feet (inherited from my grandmother). I used to joke with my mother that I could wear her shoes as earrings. I showed my publisher a photo of a baby trying on her mother’s red high heels. That got my publisher thinking, and she found the beautiful, original painting titled Work Shoes by Carol Marine. I knew it was perfect right away because I cried upon seeing it. I love how one shoe is pointing backwards to the past and the other is pointing forward to the future.

And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately spring to mind?

The three words to describe my book that come to mind are: heartbreaking/breathtaking/earthshattering (if I may be so bold).

This collection is a beautiful elegy to your mother, Florence Newman, and also traces your grieving process--grieving for the loss of the mother whose so-similar face stares back at you in the mirror. Despite the book being about your mother’s death, there’s also a sort of lightness/joy in the poems as you celebrate her life and your relationship with her. How do you simultaneously grieve, but also find joy in the relationship that continues to grow and change after a death?

I’m so glad that you see the joy as well as the sadness. Grief is a complicated thing. Sometimes the sorrow slays me. Other times, I find myself chuckling at a memory of something my mom said. And then there are the times I hear her voice in my head and I know exactly what she would say in any given circumstance. This makes me happy and sad at the same time. And yes, my relationship with her has changed since she’s died, and continues to change. I appreciate her more. I admire her more: her beauty, her humor, her “smarts” and now that she’s gone, I realize what she gave up to make my life possible.

In the poem, “A Daughter’s a Daughter,” which appears early in the book, you set up a framework for the rest of the narrative: “My mother declares …/That my fate was decided deep in her womb.//As she’s borne unto death, I will be her midwife.” Many women probably experience this moment as you did. What other realizations do you think women have as they age, and as they watch their mothers age?

I can only speak for myself. When my mother got ill, I realized that no one gets out of this alive. We all die. When my mother was told about her cancer, she said, “Everyone dies of something. This is my something.” I learned that while my mother was tough—very, very tough—even she could not beat Death. And I won’t be able to, either. My mother always encouraged me to enjoy life because it’s very short. And I understand that now in a different way than I did before she died. The sad parts of life are guaranteed. We have to make the happy times. I now try to celebrate joyful occasions, large and small, as much as possible.

One of the (many) things I love about this collection is how so many of the poems are written from the body--and then also the conflating of the mother’s and daughter’s bodies. For example, in “My Mother Has My Heart,” “My mother has my heart and I have hers,/We traded on the day that she gave birth” and in “Looking at Her,” “Yes, I had lived inside of her/Yes, I had lived outside of her.” Did you consciously write from the body, or how did this theme grow and spread within these poems? Did this consciousness of how your bodies were/are intertwined aid in the grieving process?

My mother’s body was my first home. My mother taught me in words, attitude, and action; what it was like to live in a woman’s body. I was very aware of her body as I was growing up, as she was the only other female in the house (I have two brothers). And I was very aware of how my body resembled her body: We are both short and short-waisted, and “pear-shaped.” Our bodies are not the ideal beauty standard of our society. My mother lost a lot of weight when she became ill and I became hyper aware of her body then. Not only what it looked like but how it was—and was not—functioning. What special care it needed. How my mother related to all the changes her body was going through. I also caught a glimpse of my future body if I’m lucky enough to live to be in my eighties. All grist for the poetry mill.

There are dualities of how the mother exists within this book: for example, the mother’s body when she was younger (her tiny feet, red-painted toenails), her body before death (feet swollen like mounds of clay) and then her body in death (eyelids sewn shut); what she did before (drinking tea and smoking cigarettes late at night) and her in the hospital/hospice (urine bag breaking). When reading these poems, the mother is both alive and dead, and there’s also a sense of celebrating her life/mourning her passing at the same time. What does this reflect about your experience caring for your mother, and how you coped after her death?

When I took care of my mother, I grew closer to her and more distant from her at the same time. Close in that I spent an enormous amount of time with her, doing very intimate daily tasks that had to do with her body. Plus we talked a lot about her life and about her death. More distant in that I had to prepare myself for losing her. So at times, I withdrew. Toward the end, things grew very surreal. My mother was alive and her personality, which was larger than life, was completely intact. And yet we were talking about what she wished for at the end of her life: the kind of care she requested, what she wanted to be done, what she wanted not to be done. I had to detach somewhat in order to bear those conversations. I mean, this was my mother we were talking about! Afterward I was very grateful that she was so lucid and clear and matter-of-fact about it all. Somehow that helped me cope. I knew that she was in charge right up to the end. That lifted a great burden off me. That’s a mom: taking care of her daughter to the very end.

You take inspiration from other poets like Wallace Stevens (his “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” becomes “Thirteen Ways of Looking at My Mother.”), William Carlos Williams, Elizabeth Bishop and even Dr. Seuss (“My Mother Is” and “Pills”) – and make their poems/poetic forms new in these homage poems to your mother. What attracts you to doing this, and how did you choose which poets/poems to honor this way?

My mother wanted to be a writer and for various reasons did not pursue this (though ironically, she did have one short story which was about her rocky relationship with her own mother, published in her high school literary magazine). I did not discover this story until shortly before she died and it had a such huge impact on me I wrote an essay about it.

My mother loved poetry and to honor her, I chose to use poems by some of her favorite authors as models for the poems in the collection. I think she would have been very pleased. Also, my emotions over her illness and death were so unwieldy, it helped to have a ready-made container to pour my feelings into. Some of her favorite poets are my favorite poets as well.

Many of your poems are written in rhymed stanzas, with some in more traditional formats like the troilet and rondeau. Please talk about your prosody—what draws you to these forms specifically?

I have always loved formal poetry and have written in form for most of my life. Writing in form is like solving a puzzle (my mother was, and I am an avid crossword puzzle solver). Writing in form stretches me as a poet. Every word on the page has to count and has to be the perfect word choice. Writing in form develops my ear, helps my musicality, makes me reach for the perfect metaphor. I don’t understand why more poets don’t write in form. As I tell my students, “If it was good enough for Shakespeare, it’s good enough for me.” I also love the aha! moments that occur along the way, such as a double-entendre resulting from enjambment. And forms such as the triolet or rondeau set up a pattern, so there is an expectation. Yet there are variations in the pattern which come as a surprise. So the push and pull between the expected and the unexpected create a feeling of tension in the poem which can be very powerful.

There are several poems that navigate the minute moments as your mother approaches her death and then dies (“How to Watch Your Mother Die,” “How to Watch Your Father Watch Your Mother Die” and “How to Bury Your Mother”). There are also very familiar, poignant moments of grief within poems, especially in Part Three: Quiet as a Grave, as in the poems “Looking at Her”: “Yes, I knew her very well/Yes, I had lived inside of her/Yes, I had lived outside of her”; and “Sitting Shiva: “My aunt stands to leave.’/‘Call if you need anything.’/I need my mother.” Did you see this book as a way to aid others who’ve lost a mother (biological or non) through the process?

I wrote the book, quite frankly, to help me survive the loss of my mother. I don’t know what I would have done if I didn’t have poetry to turn to. The fact that others have found the book comforting means a great deal to me. After I gave a reading from it, a woman bought seven copies (one for herself and each of her sisters). Another woman told me that after hearing the title poem, “I Carry My Mother” she felt differently about her mother’s death which had occurred more than a decade ago, than she ever had before. She realized that she, too, carries her mother in her body, and she felt the weight of her grief lessen just a bit. That meant everything in the world to me.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

The ordering of the poems came very naturally. Part One is a series of triolets that I actually wrote when my mother was still alive and I was taking care of her. I had moved back in with my parents during this final stage of her illness. Every night after I tucked her into the hospital bed we’d set up in the living room, I’d go upstairs to my childhood bedroom, sit at the desk where I’d written angst-ridden teenage poems many decades earlier, and write a triolet. Part Two is concerned with her illness and death. Part Three focuses on my grief after losing her. And it’s all bookended with a prologue and an epilogue. I feel like the poems ordered themselves.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love language, and sound. I especially love simile and metaphor. I love reading—or better yet writing—a phrase or line that makes me see something I’ve seen a thousand times before in a new and interesting way.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

Since I’ve mentioned the title poem so many times, I will share that one. I think it is the book’s heart, as it shows how I am carrying on with and without my mother at the same time.

I CARRY MY MOTHER

I carry my mother wherever I go

Her belly, her thighs, her plentiful hips

Her milky white skin she called this side of snow

The crease of her brow and the plump of her lips

Her belly, her thighs, her plentiful hips

The curl of her hair and her sharp widow’s peak

The crease of her brow and the plump of her lips

The hook of her nose and the curve of her cheek

The curl of her hair and her sharp widow’s peak

The dark beauty mark to the left of her chin

The hook of her nose and the curve of her cheek

Her delicate wrist so impossibly thin

The dark beauty mark to the left of her chin

Her deep set brown eyes that at times appeared black

Her delicate wrist so impossibly thin

I stare at the mirror, my mother stares back

Her deep set brown eyes that at times appeared black

Her milky white skin she called this side of snow

I stare at the mirror, my mother stares back

I carry my mother wherever I go

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection, especially because it moves through the stages of grief? Do you have a favorite revision strategy? And how did you revise and rework this book?

Once I start a project, once it “takes” inside of me, the writing tumbles out as though it has a life of its own. My job is to show up to the page (I write every first draft in long hand) and put in my time. I wrote the poems one at a time, rewriting over and over and over until I had a finished version, before I moved on to the next one. I absolutely love to rewrite and can pester a poem for hours, days, weeks, months, even years on end. First I rewrite in major ways going deeper and deeper into the poem. Whole stanzas are rewritten or created or thrown out. Then when the poem finds its shape more or less, I focus on individual word choice and punctuation. Then there comes a time when I know I am making the poem worse, not better. That’s the time to let go. Then I put it away for a while and come back to it with fresh eyes. Often there are a few more changes at that point, though usually not something major. Each poem goes through at least 20 drafts—sometimes more!

You’ve had such a prolific writing career, and have written in so many genres, which as you know, is hard for many writers to do. Looking at your body of work, what advice do you give to writers who are working on their first or second manuscript? And what are you working on now?

I always encourage writers to think of themselves in an expansive way. At first I thought of myself as a poet exclusively. Then I wrote a novel. Then I wrote a book of short stories. Then I wrote some children’s books. Then I wrote a novel-in-verse. Lately I’ve been writing personal essays. As T.S. Eliot said, “If you aren’t in over your head, how do you know how tall you are?” Don’t be afraid to take risks in your writing. As Annie Lamott advises, write “Shitty first drafts.” That’s the only way to grow. Also put your writing first. Develop an unshakeable writing habit. Write every day. Read every day. For more advice, see my blog post: “In It For the Long Haul.”

Right now I am working on new poems in hopes of putting together a new (unthemed) collection. Plus I am putting the final touches on a few children’s books, including a book called Sparkle Boy, which is being published by Lee and Low Books in 2017.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets/writers whose work you’d tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Here are some lines I carry with me in my head at all times. I don’t know about getting tattoos, as I am a big baby when it comes to pain. Maybe I will embroider them on a piece of clothing. Great idea!

“America, I’m putting my queer shoulder to the wheel.” –Allen Ginsberg

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”–Mary Oliver

“The common woman is as common as the best of bread and will rise.”–Judy Grahn

“You are braver than you believe, stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think.” –A.A. Milne

“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are truly good at heart.”–Anne Frank

***

Purchase I Carry My Mother from Headmistress Press.

Watch the book trailer below.

Lesléa Newman is the author of 70 books for readers of all ages including the poetry collections, Still Life with Buddy, Nobody’s Mother, and Signs of Love, and the novel-in-verse, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard. Newman has received many literary awards including poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Artists Foundation, and a Stonewall Honor from the American Library Association. Her poetry has been published in Spoon River Poetry Review, Cimarron Review, Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, Evergreen Chronicles, Harvard Gay and Lesbian Review, Lilith Magazine, Kalliope, The Sun, Bark Magazine, Sow’s Ear Poetry Review, Seventeen Magazine and others. Nine of her books have been Lambda Literary Award Finalists. From 2008-2010 she served as the poet laureate of Northampton, MA. Currently she lives in Holyoke, MA and is a faculty member of Spalding University’s low-residency MFA in Writing program. Visit her online at http://www.lesleanewman.com.

Published on January 26, 2016 14:46

January 19, 2016

Carpe noctem anthology interview with bernadette geyer

Published by Meerkat Press LLC in 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Published by Meerkat Press LLC in 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the anthology's title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up My Cruel Invention, what three words immediately come to mind?

Regarding the book’s title – once I came up with the idea of inventions/inventors as a subject, the title just popped into my head. Cruel Inventions is the title of an album by Sam Phillips, and just the thought of My Cruel Invention seemed so appropriate to me. And I couldn’t find any other poetry anthologies that focused on inventions.

Regarding the cover image – Tricia Reeks, the founder of Meerkat Press, designs her own books and she did such an amazing job of finding potential images for the cover. Once I saw this image, I had a great feeling about it. It had that little bit of futuristic/steampunk that I felt the anthology should have, as well. Tricia totally went with that idea, and this design suits the anthology better than anything I could have imagined.

To sum up the book in three words is difficult. The best I can come up with is “Poetic steampunk historian.” Now I may have to come up with a Halloween costume that matches that description.

What were you trying to achieve with your anthology? Is there a world you were trying to create?

It wasn’t that I was trying to create a world, but to illuminate the one in which we all live. If you look around you, almost everything you see was invented by someone. I love that this anthology includes poems about the invention of the safety pin and the saw gin, poems about some of the outrageous patents that exist, as well as poems about imaginary “killer apps” and futuristic robots.

Can you describe your process for this anthology?

My process for deciding which poems to include in this collection was very straightforward. I selected poems that I thought were good poems, that related to the theme, and that also had something to add to the greater conversation about the theme. No matter how good a poem was, if it didn’t relate to the theme, I had to say no.

How did you order the poems in the anthology? Do you have a specific method for arranging the poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Ordering the poems was also very important to me. We have a couple of poems about Edison, a couple about Frankenstein, and some that had a similar futuristic robot vibe. I didn’t want readers to think “Oh, here are all the poems about robots,” or “Oh, here are all the poems about crazy patents.” I wanted those poems to speak to each other from a distance, but like echoes in that they are in very specific ways different from each other.

I also wanted to move between humorous poems and devastating poems, because for all of the funny inventions there are in the world, there are also cruel ones, as referenced in the anthology title. As a reader, I appreciate when a collection doesn’t just lump poems of one type of emotion all together.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read. What does it say about the anthology?

Pinned

By Julie E. Bloemeke

1849: In debt for $15, Walter Hunt was given a piece of wire and told to invent

something to save himself from his creditors. Three hours later he revealed his

“dress pin” or safety pin. He sold his patent for $400. – Necessity’s Child: The

Story of Walter Hunt, America’s Forgotten Inventor

All the hope of a stoop.

Under birds, under a leaf

turning, copper between

the fingers. A drag. The twist

of hand, this thin filament, the words:

save yourself; you owe me.

The pressure of stairs, leading to street.

Unhinging the mind. Warming the wire

between fingers. Bend away, bend back.

The fear we owe. The mounting numbers.

Turn wire, think electric. Think: save.

Spiral back the thoughts of loss

into the pin of the mind, the tunneled

light of open, allow

the hands taking over.

Three hours. Time. Creation. Arc

to past and forward, to a letter,

a diatom, a locking thing, a heart

held in stays. A small world at the end,

a catch at the top. To protect fingers,

self. Dollar signs bent and breathing,

the small ache of empty boxes.

In these turns, a universe, the millions

we will one day hold between teeth, pinning

straps to dresses, notes to mother

on our chests, the treasure, never known,

his palm opened, the tiniest fiber

taken, his focus the failed sewing machine.

The relief of no longer in the red, the turkey

at the table, and outside the rain, now,

silver as pins, lashing the leaves,

the ground, saying, oh turn back, turn

this way. There was, in your design

the smallest sun, and we worried,

instead, about the blood.

I think this poem perfectly embodies what I had in mind when we first put out the call for submissions. The poem takes an invention so small, and illuminates the story of the invention behind it – how, and in whose hands, it came to be. The language of the poem is lovely – I, as a reader, can see the hands moving, manipulating the wire. It’s great to be given the gift of seeing something so simple in a new light.

What are you working on now?

I have a lot of projects going on right now, including a children’s book, but most of the writing and editing I am doing aside from this anthology has been for business clients. I do have a full-length manuscript of my own poetry that I have not yet been submitting because I want to get more of the poems published in journals first. I also have a chapbook that might be close to completion, but I need to wait and see if any more poems emerge that could be appropriate for it. Again, I am trying to get more of those poems into journals before I start sending the chapbook manuscript around to publishers.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Margaret Atwood, W.S. Merwin, Dorothy Parker, Mark Strand, Wisława Szymborska

***

Purchase My Cruel Invention: A Contemporary Poetry Anthology from Meerkat Press.

Bernadette Geyer is the author of The Scabbard of Her Throat (The Word Works, 2013) and editor of My Cruel Invention: A Contemporary Poetry Anthology (Meerkat Press, 2015). Her poems have appeared in 2015 Poet’s Market, Birmingham Poetry Review, Fourteen Hills, Oxford American, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. Geyer works as a freelance writer, editor, and translator in Berlin, Germany, where she also leads online professional development workshops for creative writers, freelancers, and small business owners. Visit her online at www.bernadettegeyer.com and geyereditorial.wordpress.com.

Bernadette Geyer is the author of The Scabbard of Her Throat (The Word Works, 2013) and editor of My Cruel Invention: A Contemporary Poetry Anthology (Meerkat Press, 2015). Her poems have appeared in 2015 Poet’s Market, Birmingham Poetry Review, Fourteen Hills, Oxford American, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. Geyer works as a freelance writer, editor, and translator in Berlin, Germany, where she also leads online professional development workshops for creative writers, freelancers, and small business owners. Visit her online at www.bernadettegeyer.com and geyereditorial.wordpress.com.

Published on January 19, 2016 12:16

January 10, 2016

carpe noctem Book interview with DebORAH bacharach

Published by Cherry Grove Collections, 2015 THINGS WE’D LOVE TO KNOW…

Published by Cherry Grove Collections, 2015 THINGS WE’D LOVE TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s cover image. How did you choose it?

I'm so glad you asked about the cover image. My husband and I recreated Rodin's sculpture "Cathedral" with our hands. I refer to this particular sculpture in the last line of the last poem. I also felt having our hands intertwined held one of the major themes of the book: building a life with someone else.

What were you trying to achieve with your collection? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

The book looks at many facets of women's lives--fertility, breast cancer, loving our children, not loving them. The book is also full of art, Greek and Roman gods, sexy dancers, and children.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I get something on the page, usually through freewriting. Then I let it sit, like for one month to 20 years. Seriously, I'm currently reading through journals that are from 1994. I go back through the journals picking out only the phrases and images that really grab me now. I type those into a file called "notes from journals." Then I either start crafting a cohesive set of notes into a poem or create a pastiche of different images that my gut tells me might go together. Adding in material from a completely different world is one of my favorite revision strategies. This helps me get away from linear thinking; I trick myself into making oblique connections. Once I have a draft, I go back to it regularly, playing with the images, line breaks, meter, form. My other favorite revision strategy is to squeeze. What else can I take out of the poem to make it tighter and more powerful, more musically cohesive?

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I got help! I certainly saw themes, connections between poems, images that carried through out, and rearranged accordingly, but the manuscript was getting runner-up. So, I hired Susan Rich, who is a friend, a wonderful poet, and a wonderful editor. She helped me reorder and find a new focus. I'm learning how to order a manuscript. Recently, I've been using Scrivener software to add tags, color codes, and key terms to poems. That helps me see themes and decide how I want them to intersect.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love to learn what I always knew but didn't know I knew, that moment when your breath catches and you shiver because of course "they taste good to her" (William Carlos Williams) of course what can lift me up "anything" (Muriel Rukeyser). It's that shock of recognition, even joy.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

Evening Song

When my daughter, straight from her bath,

brings her body to mine

and she has no breasts and she has only

the slightest dip in the straight line that is her

still damp with the equinox,

when she molds her body to mine,

her head under my head, her long rib cage

against my deep breasts, our heartbeats

a processional, then I know

what is in the hands Rodin

sculpted and called Cathedral.

This is the last poem in the book. I picked it to share for what it says about my process. I have loved Rodin since I was a child, and for 25 years I've tried to write a poem about Rodin. I've researched him, read Rilke's analysis of him, despaired over his treatment of the women in his life, visited his museums in Philadelphia and Paris, and written several failed poems. And then I wrote this poem in about five minutes. All that previous work built the foundation for this moment.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Have you ever despaired, desired? Have you been afraid that you didn't love someone enough? Do you want to be happy? If so, these poems will speak to you.

What are you working on now?

I'm just about done my next poetry manuscript. I'm fascinated with questions of sex and power, and in this book, I use stories from the Bible to explore these questions.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Sharon Olds

Edward Hirsch

e.e. cummings

Lucille Clifton

Mary Oliver

***

Purchase After I Stop Lying.

Deborah Bacharach is the author of After I Stop Lying (Cherry Grove Collections, 2015). Her work has appeared in Cimarron Review, Arts & Letters, New Letters, The Antigonish Review, and Menacing Hedge, among many others. She is an instructor, editor, and writing tutor in the Seattle area. Visit her online at www.deborahbacharach.com.

Deborah Bacharach is the author of After I Stop Lying (Cherry Grove Collections, 2015). Her work has appeared in Cimarron Review, Arts & Letters, New Letters, The Antigonish Review, and Menacing Hedge, among many others. She is an instructor, editor, and writing tutor in the Seattle area. Visit her online at www.deborahbacharach.com.

Published on January 10, 2016 06:43

January 7, 2016

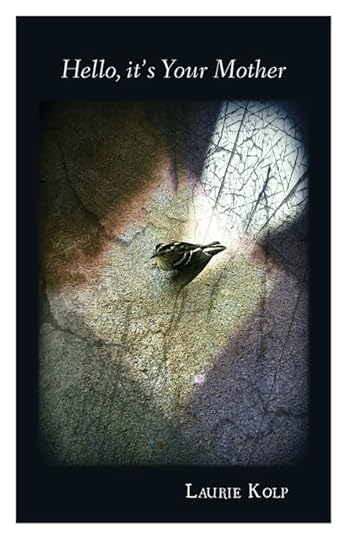

carpe noctem Chapbook Interview With Laurie Kolp

Published by Finishing Line Press in 2015 THINGS WE’D LOVE TO KNOW…

Published by Finishing Line Press in 2015 THINGS WE’D LOVE TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

My mother, bless her soul, used to call me many times a day and I’d get so aggravated about it. The title not only signifies my irritation, but it represents my longing to hear her voice again. I designed the cover from a photo I took while on a writing retreat in Arkansas. I saw it as a sign that she was there with me.

Three words: love, (dis)connectedness, forgiveness.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I wanted to create a photo album, per se, of poems that vacillate back and forth between the present and past, good and bad. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to care for my mother in the end, which came within five months of our learning her prognosis. My relationship with her had been tumultuous at times, and I realized this wasn't uncommon between mothers and daughters. I was able to forgive my mother as I cared for her. In fact, she taught me one final lesson during those months: in the end nothing matters except love. I hope Hello, it’s Your Mother will encourage others to let go of resentment and come to realize we all do the best we can in life … even our mothers.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

As you can expect, I wrote like a madwoman during this time. I wanted to capture as much of what I was experiencing as I could, and the therapeutic aspect of writing was very cathartic and eye-opening for me. After Mom’s passing, it took me several months before I could go back and look at the poems again. I like doing that anyway because it gives me time to detach, become less overprotective of my poems. Funny how that goes because delving into revisions helped me detach from my grief, too.

How did you order the poems in the chapbook? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I always print out my poems and arrange them on my king-size bed, and it seems like they always find their spot for me after I choose the first poem. I can’t really explain how that happens.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love to be wowed by imagery/language connections. Great poems I’m left wishing I’d written touch me because I can relate to them and am changed in some way by them. I also like an ending that pulls me back to the beginning for another read (and another).

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The poem I’ll share with you, "The Silhouette," is the first poem in Hello, it’s Your Mother, although it very well could have been the last. I decided to share this poem with you because … well, I love it and I hope you do, too.

The Silhouette

Cancer has worn their clothes thin--

daughter buried

next to mother

fingers stroking ragdoll arm,

head to still chest

so that we can only see

a silhouette of one.

You waited for me to come back to the hospital

before you drew your final breath. When I left

I whispered in your ear I’d be right back

to spend the night. When I returned

I whispered in your ear, I’m back.

Minutes later you were gone.

I crawled into the bed and knew

that you were gone.

When I turned your face towards mine

a stream of blood trickled out the corner

of your mouth. I dabbed it with my tissue,

placed my head atop your breathless chest

the essence of your presence like an echo,

my hope for God’s assurance--

a whisper from within that you’re okay.

It was wrong for the nurses

to tell us you might go on for days.

This process of dying takes time, they’d said.

Had I known, I never would have left.

The tear-dammed daughter

clinging to her mother’s body

until the leak finally springs.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

No fair … this is a hard question! I’m a very quiet person and I find it difficult walking up to strangers to promote myself. Let’s see. I’d start out by, “When was the last time you talked to your mother?”

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

Being a poet is living in the now. It is slowing down long enough to get in touch with your feelings and connect them to the relationships in this universe, whatever those relationships may be. I’m not too scared anymore because I’ve gotten used to the rejections. They used to terrify me, though. I love it when someone contacts me just to tell me how much one of my poems touched them. I also like listening to their different interpretation of my work.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I often write found poetry using classic novels such as To Kill a Mockingbird, Jane Eyre, The Call of the Wild, etc. In fact, when I am in a rut this helps tremendously.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on another chapbook, but just recently went back to teaching after a 14-year hiatus. That is keeping me very busy.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Julie Brooks Barbour’s Beautifully Whole and E. Kristin Anderson’s poems I wrote to Prince in the middle of the night just came in the mail. I can’t wait to delve into them.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Emily Dickinson, Maya Angelou, Robert Frost, Mark Strand, Claudia Emerson.

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

What is one of your favorite poems? "Still I Rise" by Maya Angelou.

***

Purchase Hello, It's Your Mother directly from Laurie Kolp via PayPal at lkkolpbmt@yahoo.com, or through Finishing Line Press.

Laurie Kolp serves as president of Texas Gulf Coast Writers and Secretary for Beaumont Poetry Society. She authored the full-length collection Upon the Blue Couch (Winter Goose Publishing, 2014) and chapbook Hello, it’s Your Mother (Finishing Line Press, 2015). Published widely, Kolp's poetry has appeared in the 2015 Poet’s Market, Scissors & Spackle, Driftwood Press, Concho River Review, Pirene’s Fountain, and more. Kolp is a not-so-recent graduate of Texas A&M University and lives in Beaumont with her husband, three children, and two dogs. She also enjoys running, photography, and tutoring children with dyslexia. Find her online at http://lauriekolp.com.

Laurie Kolp serves as president of Texas Gulf Coast Writers and Secretary for Beaumont Poetry Society. She authored the full-length collection Upon the Blue Couch (Winter Goose Publishing, 2014) and chapbook Hello, it’s Your Mother (Finishing Line Press, 2015). Published widely, Kolp's poetry has appeared in the 2015 Poet’s Market, Scissors & Spackle, Driftwood Press, Concho River Review, Pirene’s Fountain, and more. Kolp is a not-so-recent graduate of Texas A&M University and lives in Beaumont with her husband, three children, and two dogs. She also enjoys running, photography, and tutoring children with dyslexia. Find her online at http://lauriekolp.com.

Published on January 07, 2016 04:06

December 27, 2015

CARPE NOCTEM Chapbook interview with sarah nichols

dancing girl press and studio, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

dancing girl press and studio, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and cover image. How did you choose each ? And, if I asked you to sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind ?

I always feel like I struggle with titles. I want readers to be intrigued, but at the same time, I don’t want to give too much away. Because this is a book of found poems, I went to the text that I was working with, which was the transcripts from the film (Grey Gardens). I don’t remember how long it took me to find what could be construed as a throw-away line; a description of how “Little Edie”’s voice sounded in a particular exchange…but that voice is huge. The cover was designed by Kristy Bowen, who runs Dancing Girl Press. I gave her a photograph of Edie Beale, in which she is holding a mirror in front of her face. She is wearing a hat, not unlike one that her mother wears in the film. I wanted very much to use this photo for the cover, and I contacted Maysles Films about using it. I didn’t receive a reply, and I was concerned that there might be copyright issues. I sent the photo to Kristy, and she came up with what I think is a great image: a hat and a mirror. It’s succinct, and very right, because costume and appearance were huge in Little Edie’s life. She had modelled when she was younger, and was still (I think) a beautiful woman. If I could give you my book in three words, it would have to be voice, mother, and daughter.

What were you trying to achieve with your book ? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it?

On one level, I was trying to do a complete reversal from my first chapbook, The Country of No, which seems unrelentingly heavy and dark. I wanted to try inject levity into my work, and I don’t know that I can do that (yet) when writing about my own life. However, in adopting the personas of these two women--who were very much alive--I was able to do that. That isn’t to say that Edie isn’t serious, or doesn’t hint at dark things, but it goes about it in a different way. As for creating a world, well, the Beales had already presented their lives to the world. It’s been made into a musical, and a kind of backstory appeared in the Jessica Lange/Drew Barrymore film. Perhaps I was trying to approximate what would happen if Little Edie wrote a book of poems; she speaks about writing a book during the film. I think that I wanted to show that their home, Grey Gardens, was not only a physical place, but also a state of mind that was difficult to leave.

I read in another interview where you said that the poems in Edie (Whispering) came quite easily to you. Why do you think that is? Of course, Grey Gardens, which explores the daily lives of two of Jackie Kennedy Onassis’ eccentric female relatives—Edith Bouvier “Big Edie” Beale and her daughter Edie “Little Edie” Beale—who rarely leave their Long Island estate and essentially live in the past, is a story of two very captivating women.

I think it was easy for me because in a way, I knew this story of a daughter and a mother who lived in their own world. Without going into too much detail, I had lived this. Certainly not to the extent that the Beales did, but a variation of it. The material was very close. I also feel like I was finally listening to Edie when she spoke in the film; there’s a cadence; she’s performing. It is its own strange poetry, and it was a matter of getting it down.

Talk to me about found poetry—in Edie, you created stunning poems from the conversations that Edith and Edie had with Grey Gardens filmmakers Albert and David Maysles. Get ready: I have a few questions. First, how did you discover found poetry? Second, describe your process for creating these poems. Third, what do you say to critics who label found poetry as unoriginal?

I discovered found poetry in a workshop that I took with Ravi Shankar at the Wesleyan Writers Workshop in 2009. He talked about the cento, which I had never heard of. Examples were presented, and we were urged to try our own. I am also interested in collage as an art form, and this struck me as a kind of verbal collage. I would write non-found work, but I would come back to found poetry every so often, and I wondered if I could sustain it for a whole book. In 2013, I was given the opportunity to participate in The Found Poetry Review’s National Poetry Month project, Pulitzer Remix, in which I created 30 found poems out of Philip Roth’s American Pastoral. Since then, a great deal of my work has been found. My process for the Edie poems had me watching the film more than once, and ultimately had me “hunting and gathering” lines from the printed transcripts of the dialogue (the Beales speak rapidly, and while I took notes when I watched the film, it was difficult to keep up). I debated about using erasure techniques, but decided not to. I wrote down lines, focusing on a theme for a poem, casting some of the lines aside, bringing in others. I would try to encompass some that might not have worked in one poem, and put them in another. I took a break from the material for about two months; this is a hermetic world, and I needed critical distance to finish it, and make it as good as it could possibly be. As for critics of found poetry, all I can say is that it takes as much work, or perhaps more, to construct a found poem. It’s citing sources. Searching through pages of text. If one is making an erasure, that might mean blacking out a block of text with a marker, or daubing white-out over a line (if you aren’t working with Photoshop; and that takes a deft hand, too). For the Pulitzer project, 85 of us had to make poems that were completely unrelated to the books that we were working with. That’s not original ?

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection ? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

My writing process for this particular collection involved, first of all, watching the documentary Grey Gardens. When I watched it last year, I listened to the rhythms of Little Edie’s voice, the repetitions. And then, BOOM! It occurred to me that she was speaking in poems. Her daily speech, how she was interpreting, and living in the world, was colorful, imagistic. Her life, and her mother’s, would be insane to most of us. I wanted to capture some of that ability to transform her existence into a kind of performance. I then found a book which was written by Sarah and Rebekah Maysles (the daughters of David and Albert Maysles), also entitled Grey Gardens, and which contains all of the transcripts from the film, along with photographs and illustrations. I went through the text, sifting for lines that would make up the poems; I tried not to become repetitive in terms of word choice. In terms of revision, I frequently gather miscellaneous lines and see what works in an almost jigsaw puzzle fashion. It’s a piecing together of elements. There are times when it seems clear, and at other moments nothing comes. Patience for the reveal is key for me.

You don’t explicitly identify which Edie is speaking in the poems. Sometimes it’s obvious that’s the elder Beale or the younger; sometimes it’s not; and sometimes it’s an intermingling of voices in these poems—these two misfit women with huge, engaging personalities. Did you have a specific intent in treating the poems that way?

There are times, in the film, where each woman gets a hearing, times when they are fighting each other, and other times where there is some harmony between them, however briefly, and still other moments where they are speaking to each other, but are clearly not listening, or hearing only what they want to hear. I wanted to keep that in mind when I wrote the poems. I kept asking myself whose voice I wanted to give more weight to. It probably came down on the side of Edie, and it was trying to temper both of their personalities. Sometimes I felt like I just wanted to give them both free reign in the poetic space, so I did.

How did you order the poems in the collection ? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in ?

I don’t know that I had any specific plan in mind when I arranged the poems in Edie. I numbered them. For example, “Grey Gardens Poem One,” and I just kept going for the duration of the writing of it. I liked the order they were in, and I don’t think that I rearranged them. I wanted to have the stronger poems at the front of the book. For my first book, it was a matter of putting the newest material at the front; it represented a kind of culmination of everything that I had written up until that point. There was probably more tinkering involved. I tend to shuffle papers around, rather than, say, put them on the floor to see what kind of order they should be in.

There’s an interesting dynamic at work in the poems. The Edies both are trapped by certain aspects of their lives, but then stay in their self-imposed confinement. “Big Edie” lives in her past, yearning for the woman she says she was (in “One Sings,” “Bring in the orchestration./my voice/the way it was when I/was/forty-five years old.”) “Little Edie” struggles against still living with her mother and never marrying, but seems to rationalize that with her fears of madness (in “Not All There,” “they were trying to prove I was/ Craaazyyy.”) Please tell us about how that idea of confinement/yet moments of contentment in those confines plays a role in the chapbook. Are there other themes that you would like readers to recognize?

Well, the relationship between the Beales, and the house they share is symbiotic in its way. Big Edie is determined to stay, and rule over this place, but yearns for the singing career that might have been hers. Little Edie harbors the young woman’s dream of running away to the big city and making it on the stage (and she did indeed have a cabaret act after Grey Gardens was sold), but where else but that environment could she give free reign to her dances, her recitations, and musings ? The house both nourishes and destroys. The house is a stage, and that’s where the contentment comes in. But then it becomes a trap, with holes in the roof, wild animals in the attic, and fleas so thick that the Maysles brothers had to put flea collars around their ankles during filming. This was a completely made-up world that existed in parallel to the more staid one of the Hamptons. I wanted to offer a glimpse into that. I don’t know if I did. I also wanted to people to be aware that this is, at its core, about a daughter and a mother; there is genuine love, and genuine loathing on display. Yes, I think that there was a certain “playing up” to the camera, but for the most part, I think that that was what is like when the camera wasn’t there. I think that I also want readers to be aware of the undercurrent of loss. I wanted humor, yes, but this is a world, and people, who are wedded to the past.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

When I’m reading , I like to find things that stun: a phrase, maybe; an image. Does it haunt me? Make me laugh (although this is more rare)? Does the writer love the language? These are all things that I wonder about. As for my own writing, I tend to write from a place of obsession. I’ll have something that’s stuck in my head, and I wonder how it might come out in writing. It sometimes approximates what I thought. In many instances, however, it morphs into something far different. Can I say it in a concise way? Poetry, for me, demands a kind of precision. Sometimes I reach that, but it’s frequently a case of “failing better,” to paraphrase Samuel Beckett.

Can you share an excerpt from your book ? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read--did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection ? Is it your book’s heart ? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The Best Costume

A lady is a lady is a lady,

and I

don’t like women in skirts.

I can’t help it: I

like to wear certain things.

A kimono, a cape, pants

under the skirt, stockings

up over the pants----

I have to think these things up, you know,

and

this is the best thing to wear for the day.

I chose this poem because in listening to Edie Beale talk about her clothing, I realized that yes, I could make poetry out of her dialogue. It wasn’t the first poem that I wrote for the book, however; it was the third, but it some ways, it did galvanize the rest of what I wrote. It was perhaps then that I realized that I could keep going with these poems; that it was a viable project. I think that there are many hearts in this book. But this is probably one of them. In her own way, Edie Beale has become a fashion icon, and her clothing is very much a performance. Fashion is also a huge part of who I am, so I felt very close to this poem.

Your use of line breaks is very strategic, and gives the poems a certain cadence and sense of space. Do you do that consciously, and if so, how do work the breaks to fit your intentions to guide how the poems are read ?

When I was starting out writing out, I feel as if my poems were longer. As I’ve gone along, the lines have gotten shorter, the breaks more staccato (at least to me). At times in the film, both women could be very expansive, and then lapse into silence, or veer into an epic fight. I wanted to see what I could do that might mimic that. There are times, I think, where the poems are having conversations with each other, as the Beales did, and at other times, it’s definitely a lone voice addressing an audience. Perhaps the breaks make things more dramatic. I also think that “Little Edie” could be quite breathless in her speech--it would all come out in a rush, and you can’t keep up--and I wanted to be true to that as well. It was important that I honor the voices of these women.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say ?

I might tell them about the history; the women's connection to Jacqueline Kennedy. I might also say that while this is in many respects a bleak story, it also has its humorous moments. I’m out of practice when it comes to heckling strangers to read books. I used to be able to persuade people (friends and strangers) to read Richard Yates.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

Being a poet, for me, means that I can tap into this kind of mystery that’s going on all the time. It’s like being a kind of tuning fork for language. It allows me to make sense of the world, or to reorder it. What’s scary about being a writer is being confronted with the fact that it will never be perfect; I will never hit it exactly as I want it. What I do after facing that moment is where whatever talent I have comes to bear: How do I solve the problem ? It is, for me, a running off of that proverbial cliff. But there is also great joy to be found in that leap. I love the happy accidents of language. With this project, they were everywhere. I felt, from the beginning of it, that there was something amazing at work. To be able to see that, and not let go, that is what gives me joy.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you write poetry?

I read a lot of novels and non-fiction; this can take the form of history, memoir, or biography. I look at a lot of art books. I pay close attention to song lyrics and screenplays.

What are you working on now?

In all honesty, I am casting about for a new project in terms of poetry. At the time that I was working of the Grey Gardens material, I didn’t really share that I was working on it. I held it close. I have some ideas, however! I am also making notes for an essay about Depeche Mode’s Violator that I am going to be writing for the RS 500 project. It will be published in March.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I’m reading Garth Risk Hallberg’s epic of 70s New York, City on Fire. He overshoots sometimes, but the story is compelling enough for me to keep going. I like getting lost in novels. I also just started Bernard Sumner’s autobiography Chapter and Verse: New Order, Joy Division and Me. The music that obsessed me as a teenager still preoccupies me. I like to know the people, and the places, that it came from.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

1. Sylvia Plath. 2. Emily Dickinson 3. John Berryman 4. Anne Sexton 5. Radiohead.

What’s a question you wished I asked ? (And how would you answer it ?)

Is poetry a spiritual practice for you? I would say that yes, it most definitely is. It pierces the veil of the world. To be granted that is a gift.

***

Purchase Edie (Whispering): Poems from Grey Gardens (dancing girl press, 2015).

Sarah Nichols is the author of Edie (Whispering): Poems from Grey Gardens (dancing girl press, 2015), and The Country of No (Finishing Line Press, 2012). Her poems have appeared in The Found Poetry Review, Thank You for Swallowing, and Right Hand Pointing. A passionate cinephile, her film criticism has appeared in Senses of Cinema and desistfilm. She lives in Connecticut.

Sarah Nichols is the author of Edie (Whispering): Poems from Grey Gardens (dancing girl press, 2015), and The Country of No (Finishing Line Press, 2012). Her poems have appeared in The Found Poetry Review, Thank You for Swallowing, and Right Hand Pointing. A passionate cinephile, her film criticism has appeared in Senses of Cinema and desistfilm. She lives in Connecticut.

Published on December 27, 2015 07:31

December 21, 2015

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Alexis Rhone Fancher

THINGS WE’D LOVE TO KNOW…

Let’s start with the chapbook’s title, State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies, and your cover image (and also the haunting images inside). How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your chapbook, what three words immediately come to mind?

I wanted the cover of the chapbook to have a certain gravitas. My publisher at KYSO Flash Press, Clare MacQueen, and I agreed that there would be no photos on the front cover. Just words, plain, and sobering. The images inside of the chapbook were arrived at over several weeks, after we had ordered the poems. Again, it was a collaboration. I provided Clare with about a dozen of my photos I thought might be right, and we whittled them down to eight. The photo of my son at the end of the book has always been a favorite. He looks so happy. As for the self-portrait on the back cover, I shot that shortly before Josh died. Every time I see it, I remember exactly how I felt. Like a train wreck.

Three words to describe the chapbook: Tragedy. Transcendence. Grace.

This collection is a series of elegiac poems for your son Joshua, who passed away from cancer at age 26. In the poems you fill the gap your son left with such clear bits (a text, a voicemail, his room intact, a photo of his beautiful girlfriend) and memories of him (on the court playing basketball, after his arm amputation). For example, in “Snow Globe,” the narrator wears worrying finger marks on the outside of the velvet bag that contains her son’s ashes—she contemplates smearing ash on her forehead because, “Unless I look in the mirror/ I can’t see him.” In “My Dead Boy’s Right Arm,” the narrator just wants her son to come back and say, “Mama, really, it’s not so bad/ being dead at 26.” As a mother who writes, do you feel that this collection has helped memorialize your son/kept part of him alive in these poems? How have these poems helped people who knew him—and grieve for him?

I don’t know if it is possible for me to write anything good enough to memorialize my son properly. He was a fine human being. Compassionate, with heroic courage. Friends and family have read several of these poems as they were published in journals and lit mags. I hope they brought some comfort. I don’t know. When the chapbook comes out, I’ll see how it lands.

In several of the poems (for example, “Death Warrant” and “The Competition”), you confront hurtful things people have said to you in the wake of your son’s passing. In “Over It,” a friend asks the narrator two weeks after her son’s death if she’s over it, and the narrator’s scathing response in the poem is: “I want to ask her how her only daughter/ is doing. And for one moment I want her to tell me she’s/dead so I can ask my friend if she’s over it yet./ I really want to know.” Have you written this collection both as a way to communicate with people who are grieving and to people who need to know how to talk with those in mourning?