Nicole Rollender's Blog

September 19, 2018

CARPE NOCTEM BOOK INTERVIEW WITH: Geraldine Connolly

Terrapin Books, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Terrapin Books, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Wings. Feathers. Flight. I wanted to express the notion of staying aloft while heading through turbulence. An aileron is a hinged flight control surface on an airplane’s wing. It provided the central metaphor of the book which is trying to find balance, to stay aloft in the midst of tragic events.

Finding a cover for an abstract idea like endurance was difficult. So I first went with the idea of representing the lost family farm with a photo of a barn. Fortunately, my wonderful editor, Diane Lockward, came up with more exciting alternatives. She found the work of a feather artist, Lewis Grimes, and one of his pieces was very striking. It haunted me. It’s an explosion of fanned white feathers set against a black background with a scatter of blue dots. It seemed metaphorically perfect.

I did an entire interview (read it here) just on the process of finding the right cover.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Aileron is a collection about facing loss, of a rural childhood, a family farm sold to a mining company, the fracture of our family that ensued. Memory is a key motif (memory “the weight of stones” from the poem Aileron) and staying power, after the weigh-down of tragedy and disappointment. The collection is firmly rooted in the natural world, the landscapes of a Pennsylvania childhood, of Montana summers and a move to Arizona, to the Sonoran Desert which offers a strange but healing landscape, a mixture of oddness and wonder. Birds, Wings. Trees. The elements of air rule this collection. The central metaphor of the aileron, which controls balance on an airplane wing, suggests the importance of not surrendering to sadness but finding new direction, staying on course.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I try to write freehand every morning. I empty my hand into a notebook. Then I put the poem away for several weeks and come back to it looking at the writing with a critical eye, as though someone else had written it. I circle the parts that are working and cross out the weak parts. I write more if I have to. I often read a poem into a tape recorder and play it back to hear if there are any problem spots.

I feel that as William Matthews used to say: “Revision is not cleaning up after the party It IS the party.” I have a writing group that meets on a weekly basis. Having their input speeds up the revision process. I have a tendency to go metaphor crazy and to overwrite. My colleagues help me find the metaphors and similes that work well and the ones that don’t, so I can cut out the excess. Endings are always a challenge. If the ending isn’t working, I leaf through some books of poets that I admire and try to figure out, craft-wise, what different options might be for ending my poem. Sometimes the ending doesn’t happen for a long while. It is hard to be patient but one must be patient with an ending. It’s a very important place in the poem.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

For me, organizing a collection is intuitive. I knew I wanted to have a story arc for Aileron and some central motifs. I sought the strongest poems for the beginning. They had to be poems that set the theme. Since the theme of losing my inheritance of the family farm is sad, I tried to intersperse some praise poems to lighten the mood. I also like the idea of “dovetailing’, taking a word from the ending of one poem that links somehow to a similar word in the next poem. For the final poem, I wanted to end the book on a positive note, so the final image is a swing flying upward into open space.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart?

This is a poem that is the book’s heart. It describes the emotional drama at its core.

Legacy

They covered my mother’s farm

with drilling rigs,

knocking down the house

like a stack of blocks.

So we must live now

without the hayfield and the creek,

without the silo, the corncrib,

the orchard, the creek bed.

We will breathe the summery

air only in dreams

where we make soup with water

and bits of stone,

slash the onions

into slivers of regret.

A plume of smoke

rises grimly from the barn.

Since someone has forgotten

to latch the gate,

a thief has entered

the garden,

grabbing the carrots,

ripping onions from their beds

while we watch from

our distant dwelling,

dreaming the past

still exists,

floating on its raft of broken bread.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

This is my new book, Aileron. It tells a story. It’s a love story about loss, in this case a lost and destroyed farm. And there are poems of praise about people and places I’ve loved. It’s accessible, written in plain language and I’ve been told it’s a good read. I think you’ll enjoy it.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

For me, writing is about making. I enjoy making things and poetry offers me a chance to make something that both searches for truth and attempts to make sense of chaotic events. I know that’s impossible but I enjoy trying. Poetry is where I put the emotional overflow of my life. It’s a calming lake on which I place my carefully crafted paper boats.

The scariest thing for me would be not being able to write. It is so necessary in my life. Without my writing I would feel aimless and unfocused. My life would feel empty and without purpose.

And I am gratified when someone finds my work and writes to me, telling me that they were moved by it. Connecting that way with another person is enormously satisfying.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Dictionaries, novels, guidebooks, atlases all have wonderful, unusual words that are sources for poetry. Reading specific guidebooks can help enrich the word choice and increase the authority of a poem.

What are you working on now?

The next poem. Always, the next poem.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I’ve been enjoying Mary Ruefle’s Selected Poems. She is so imaginative and honest and her work has a wry knowledge of self, a sense of humor about accepting what it means to be a flawed human. I also loved Stepping Stones, a book of interviews with Seamus Heaney which serves as a book-length portrait of Heaney and offers his reflections on his writing and career.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bishop, Seamus Heaney, C.D. Wright.

***

Purchase Aileron.

Geraldine Connolly is a native of western Pennsylvania and the author of four poetry collections: Food for the Winter, Province of Fire, Hand of the Wind , Aileron as well as a chapbook, The Red Room. She is the recipient of two N.E.A. creative writing fellowships, a Maryland Arts Council fellowship, and the W.B. Yeats Society of New York Poetry Prize. She was the Margaret Bridgman Fellow at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and has had residencies at Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and The Chautauqua Institute. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Georgia Review, Cortland Review and Shenandoah. It has been featured on The Writers Almanac and anthologized in Poetry 180: A Poem a Day for American High School Students, Sweeping Beauty: Poems About Housework and The Sonoran Desert:A Literary Field Guide. She lives in Tucson, Arizona.

Geraldine Connolly is a native of western Pennsylvania and the author of four poetry collections: Food for the Winter, Province of Fire, Hand of the Wind , Aileron as well as a chapbook, The Red Room. She is the recipient of two N.E.A. creative writing fellowships, a Maryland Arts Council fellowship, and the W.B. Yeats Society of New York Poetry Prize. She was the Margaret Bridgman Fellow at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and has had residencies at Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and The Chautauqua Institute. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Georgia Review, Cortland Review and Shenandoah. It has been featured on The Writers Almanac and anthologized in Poetry 180: A Poem a Day for American High School Students, Sweeping Beauty: Poems About Housework and The Sonoran Desert:A Literary Field Guide. She lives in Tucson, Arizona. Visit her online at www.geraldineconnolly.com.

Published on September 19, 2018 21:00

May 10, 2018

CARPE NOCTEM INTERVIEW WITH LISA STICE

Middle West Press, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Middle West Press, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Those in the military or related to those in the military are quite familiar with “permanent change of station,” but civilians might not be. It is the phrase used for orders to a new duty station. I wrote these poems after we received out last PCS: write before the move, while in hotel rooms across the country, and after we arrived at our new station.

The cover art is like a kindred spirit to me. The upper image is Little Girl in a Blue Armchair by Mary Stevenson Cassatt. In this painting, I see my own daughter and dog (the muses of my collection). The lower image is of a machine gun atop a Humvee (photo by U.S. Marine Cpl. David Ricketts). While it seems to contrast with the upper image, it is part of the reality of a military family.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

When we made this last move, my daughter was two. Already confused by that crazy time of toddlerhood, this move that took her away from the home, scenery, activities, and faces she knew to a place completely foreign to her was quite traumatic. I struggled to help her cope with the changes as I was also in new place with no friends or family, and my husband’s job often continued to take him away. Even my little dog (a Norwich Terrier) had trouble coping, and he became our self-appointed sentry. The poems became a way to identify with self and place, to make sense of chaos and change, and a way in which to bridge the seemingly contrasting worlds of civilian and military.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection?

Some of the poems are cento-like in that I borrow words and phrases from classic children’s books and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. During this time of change, our constant was the nightly bedtime story ritual, after which I would read from The Art of War (my survival manual of personal battles), then spend some quiet time writing. In my poems, the language from my recent readings would merge with my own words. With each poem, I felt stronger and better able to help my daughter.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love to be surprised when I read a poem. That surprise might come from the word choice, juxtaposition of images or phrases, new perspective, structure, etc.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

“Such is the Art of Warfare” lives in the middle of the book. I feel like it best shows that strength that can come from vulnerability/fragility. It’s first home was in Shantih Journal volume 2, issue 1.

Such Is the Art of Warfare

Sometimes her mother would worry

about her, that she would be lonesome

all by herself, with a dog for a brother

in this out of the way place

where we are only acquainted

with neighbors, and only some.

This is the art of studying circumstances.

She pitched up camp

between sofa and coffee table

under pillows and cushions

she said, I like it better here.

She liked to smell the flowers

hand-picked from air

hold their invisible petals

against her face, breathe

the scent of once upon a time.

This is the art of studying moods.

And so her mother knew

she was not lonesome:

she was like a mountain

like a fire, like a thunderbolt.

Her mother whispered,

let your plans be impenetrable.

This is the art of self-preservation.

*some words borrowed from The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf (“Once upon a time,” “liked to sit quietly and smell the flowers,” “he would sit in the shade all day and smell the flowers,” “Sometimes his mother…would worry about him,” “She was afraid he would be lonesome all by himself,” “’I like it better here’”) and from “Maneuvering” The Art of War by Sun Tzu (“pitching his camp,” “out of the way,” “we are acquainted,” “our neighbors,” “be like fire,” “like a mountain,” “let your plans be dark and as impenetrable as night,” “fall like a thunderbolt”)

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

For me, being a poet is about communicating with those who came before me, with the world currently around me, and whatever the future will become.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Definitely! This book is a great example of that with its borrowed phrases from classic children’s stories and The Art of War. Poems not in this collection have been inspired by nursery rhymes, military manuals, Marine Corps speeches, constitutional laws, and such. I love pulling from my library (and from my husband’s and daughter’s libraries).

What are you working on now?

I have a collection that’s been hanging out in submission queues for a little over 10 months now. Those poems are inspired by and in conversation with poets who write/wrote in times of conflict. I have a couple collections in the works. One is nature poetry and the other is inspired by forces in physics.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Every Atom by Erin Coughlin Hallowell is a fantastic new book. I also had the pleasure of reviewing a galley copy of Dirt and Honey by Raquel Vasquez Gilliland (amazing!), which launches May 18.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Ciaran Carson, Emily Dickinson, Wilawa Szymborska, Seamus Heaney, Elizabeth Bishop

***

Purchase Permanent Change of Station (Middle West Press, 2018).

Lisa Stice is a poet/mother/military spouse, the author of two poetry collections Permanent Change of Station (Middle West Press, 2018) and Uniform (Aldrich Press, 2016), and a Pushcart Prize nominee. She volunteers as a mentor with the Veterans Writing Project, as an associate poetry editor with 1932 Quarterly, and as a contributor for The Military Spouse Book Review. She received a BA in English literature from Mesa State College (now Colorado Mesa University) and an MFA in creative writing and literary arts from the University of Alaska Anchorage. While it is difficult to say where home is, she currently lives in North Carolina with her husband, daughter and dog. Visit her online at lisastice.wordpress.com.

Lisa Stice is a poet/mother/military spouse, the author of two poetry collections Permanent Change of Station (Middle West Press, 2018) and Uniform (Aldrich Press, 2016), and a Pushcart Prize nominee. She volunteers as a mentor with the Veterans Writing Project, as an associate poetry editor with 1932 Quarterly, and as a contributor for The Military Spouse Book Review. She received a BA in English literature from Mesa State College (now Colorado Mesa University) and an MFA in creative writing and literary arts from the University of Alaska Anchorage. While it is difficult to say where home is, she currently lives in North Carolina with her husband, daughter and dog. Visit her online at lisastice.wordpress.com.

Published on May 10, 2018 21:00

April 24, 2018

CARPE NOCTEM INTERVIEW: NANCY REDDY

EVERYTHING WE'RE DYING TO KNOW

EVERYTHING WE'RE DYING TO KNOWLet’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

For my three words, I’d say – swamps, saints, and hurricanes. The book is set in south Louisiana, just before and after a hurricane, and it follows the figures – saints, a siren, a collection of sibyls, a handful of neglectful gods – who move through that magical liminal space that’s both water and land.

The book is named for Acadiana, a region of south Louisiana. And the cover is a photograph by Lise Latreille, whose work I adore. I first came across her photography when the editors at Radar paired my poems with her photographs, and I loved how they evoked the landscape of the book.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create? Who lives in it?

As a writer, transformation is one of my central obsessions – and natural disasters often mark such a clean before and after. I lived in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, and in the years afterward, when I lived in Houston, we had two more hurricanes. So this book was a way of thinking through – in an indirect way – that experience of transformation through natural disaster. This book imagines the swamps and bayous that surround south Louisiana as a liminal space – between this world and the next, between the mortal and quotidian and the supernatural. It’s a landscape on the precipice of disaster – “the storm that’s said will break us,” as Saint Catherine describes it in one of the poems – and the book watches as the townspeople try to safeguard against harm and as the saints and sibyls do what they can to help.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

As I revised the collection, the poem took on what feels to me like a kind of chronological structure – anticipation of the hurricane and reckoning with the destruction afterwards. I also paid attention to distributing the different voices in the book, so that, for example, I put the kind of pseudo-Christian ritual of “The First Miracle,” in which a father leads his children to the marsh’s edge after he performs an early morning service, against the pagan divining in “Signs Resembling Sacraments.”

What’s one of the more crucial poems in the chapbook for you? (Or what’s your favorite poem?) Why? How did the poem come to be? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book, or somewhere else in the process?

One of my favorite poems in the book is “Saint James at the Ascension Parish Drive-In,” in which a kind of modern-day Saint James skulks around a drive-in, obsessing about the immoral behavior of the women in town, before he comes across a girl who’s sleeping while her older sisters flirt. He’s watching her with this kind of unsettling intensity, and though he claims in the last line that “when I left her she was still unharmed,” there’s also, I think, this feeling that something bad has happened or is about to happen to the girl – perhaps just the vulnerability that’s an inevitable part of encroaching adolescence. The poem was one of the earlier ones written for the collection, and it opened up several doors for me, in terms of the writing. Though I was certainly familiar with the idea of writing through persona, Saint James felt urgent to me – like I was actually channeling a voice, rather than using a figure to say something about my own life, which is probably what I’d done with persona before. And after I wrote that poem I figured there had to be other saints wandering around, and I wrote “Saint Catherine Takes the Auspices” and “Saint Charlene Offers Up Her Suffering,” about the fascinating folk saint Charlene.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

For me, writing is a way of being present and attending to the world. When I’m writing regularly, I move through the world differently – I’m more engaged and attuned to the people and places around me.

I’ve heard poets say they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you? If not, what obsessions or concerns reoccur in your work?

You know, I really thought, with the second full-length I’m working on now – which is largely about pregnancy and early motherhood – that because my subject was so different than my first full-length and this chapbook, that it would be a definitively different set of poems. But even though I’m writing about new things, I’ve found that many of my obsessions have just come right back – and some feel more pressing now, like questions of how we use faith and ritual to comfort ourselves in the face of the unknown, the question of the afterlife. Now that I have kids, the world seems both more magical and more perilous, and so that new lens has altered how I approach those old obsessions.

Do poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

I think poets have the same responsibility everyone has to pay attention to what’s happening in the world, and to intervene in whatever way we can – but I also think it’s important to remember that poetry is not political action. Writing a poem about gun violence, for example, doesn’t substitute for voting or calling your congresspeople.

I like this question, though, because it helps me to think about something I’m struggling with in the second full-length I’m finishing now, which is largely about pregnancy and early motherhood, including a range of postpartum struggles. And I’ve worried sometimes that maybe the book is too small, because it takes on these subjects that are thought of as domestic, as women’s work. (These recent poems in Tinderbox are a good example of part of the scope of the book – one’s more personal, and the other looks back into the world, at the story of the girls stolen by Boko Haram, from the eyes of a woman who’s been forced to think differently about vulnerability and harm because she’s caring for infants and small children.) But I also think that’s true nonsense – this persistent, insidious idea that women’s lives don’t really count, that if a woman writes about something that’s happened to her, it’s “merely” personal, it’s just private or confessional. I resist that. I think women writing their lives – and particularly writing against conventional and inscribed narratives – remains essential feminist work.

***

Purchase Arcadiana .

Nancy Reddy is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Pleiades, Blackbird, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University in southern New Jersey. Visit her online at www.nancyreddy.com.

Nancy Reddy is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a 2014 winner of the National Poetry Series, and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018). Poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Pleiades, Blackbird, The Iowa Review, Smartish Pace, and elsewhere. The recipient of a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and grants from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Sustainable Arts Foundation, she teaches writing at Stockton University in southern New Jersey. Visit her online at www.nancyreddy.com.

Published on April 24, 2018 15:39

February 7, 2018

CARPE NOCTEM: KAREN PAUL HOLMES

Terrapin Books, 2018 Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Terrapin Books, 2018 Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?First, Nicole, thank you for this interview and your great questions! The title comes from the book’s final poem, “Crossing the International Date Line,” though the words “no such thing as distance” are not in the poem exactly. As I considered titles, this one best captured the themes running through the book, which are immigration/cultural traditions kept alive in the US, family, travel/change, loss/gain, acceptance. For practical reasons, I chose a long and somewhat unusual title because it’s more likely that an online search for it will be successful. For example, I originally titled the book, “Crossings,” which seemed perfect because of its multiple meanings, but if you Google a generic word like that, my book might never come up. Because I’m also a marketing professional, I didn’t think that would be wise. However, I may have kept “Crossings” if I hadn’t found one that worked as well or better creatively.

3 words: Growth, Relationship, Spirit

My publisher (Diane Lockward) and I kicked around ideas for a cover image and searched through some royalty-free photo sites. Since I love original art, and two of my sisters are artists, I asked them whether they had anything that loosely fit the theme, and also was photographed with a high enough resolution to reproduce well in print. I chose a “mixed water media with collage” by my sister, Eileen Millard, because I loved the colors, the circular design, and the multiple ways in which it fit the book’s title, especially the vanishing point image, and the global/celestial elements.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create? Who lives in it?

Hmmm, I didn’t set out to write this book exactly, but as I pulled together poems for it, multiple themes emerged. I mainly wanted to honor the story of my parent’s immigration to the US – my dad from eastern Europe before WWII; my mother from Australia as a war fiancée. The Macedonian traditions I grew up with added a richness to my life that I wanted to capture. That’s partly why I included recipes in the back of the book. I’m also obsessed with the intersection of spiritual philosophy with quantum physics, especially regarding the concept of time. So in these poems, directly or indirectly, I deal with this whole question of time and distance, and how that affects memory and loss and acceptance. Themes of music and dance are woven throughout, so I guess you could say the book is a sort of dance through time.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Each month, I attend a poetry critique group that I host and a free community workshop by Katie Chaple, sponsored by the program Tom Lux started at Georgia Tech. I find those invaluable for getting feedback on my poems. Because I’m a bit of a workshop junkie, other poems in this collection were workshopped with Tom Lux, Travis Denton, Laure-Anne Bosselaar, David Bottoms, Denise Duhamel, Cecilia Woloch, and Dorianne Laux. I also paid for a critique of several poems with Ginger Murchinson, and a full manuscript edit by Jenn Givhan. Once I have others’ input, I have to decide what makes the poem work for me, and I usually revise or tweak about a million times, trying to put the poem away for a while between revisions.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

At first, I ordered the poems in a somewhat logical order, but got feedback from a couple of editors that I shouldn’t frontload with childhood and parent poems, so I ended up playing with the order in a number of ways. Once I even did a spreadsheet that categorized poems by theme, point of view, etc. to make sure I wove those throughout the manuscript instead of clumping them together. I paid particular attention to the flow from one poem to the other – looking at how the last line of a poem worked with the first line of the next, and also paying attention to the “mood” of each poem. To avoid jarring the reader inappropriately, I didn’t want a funny poem to follow a dead-serious one or vise versa. The last poem remained the last poem throughout all these revisions, but I changed out the opening poem many times.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

A connection to the poet or the voice in the poem. I want to feel something when I read a poem – laughter, an aha, an empathetic cry, and/or a “yes that’s me, exactly!” If it makes me laugh, shiver and cry, I’ll dog-ear it in a book. I also appreciate sheer beauty and precision of language, but if a poem’s too abstract, I’ll turn the page without finishing it.

What’s one of the more crucial poems in the book for you? (Or what’s your favorite poem?) Why? How did the poem come to be? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book, or somewhere else in the process?

The poem, “Death Prefers Blonds,” springs to mind. It tells an unusual and true story, while capturing something of my mother and the idea that we are not really our bodies, but spirits. I’m not even sure how the writing of this poem relates timewise to the writing of other poems. There was a period where I was reprocessing my mother's death, and I knew she’d play an important role in this book but did not write the poem for the book. It was published in Pilgrimage Magazine in 2015.

Death Prefers Blonds

There was a wig mix-up

at Pavich funeral home.

We had a chance to switch

back to the gray bob—it had suited

Mother for doctors and church

those last few months. But

we knew she’d rather dazzle

everyone from her casket

as a stylish ash blond.

She looked 70 not 87

with the wrong longer hair

and undertaker’s make-up

that reshaped her

grown-gaunt cheekbones

into Faye Dunaway’s.

One catty mourner hissed,

It doesn’t look a thing like her--

a boon to us: easier to let

that blond descend

into Madame Tussaud’s museum

while our real mother

joined us in prayers

carried on wisps of frankincense

past the gold dome of St. Nicholas.

Tell us something about the most difficult thing you encountered in this book’s journey. And/or the most wonderful?

Journey is a good word. When I first got word from Diane Lockward that she’d selected my manuscript for publication, a hurricane was ravaging the island of St. John, where my daughter had just moved to teach. So in the midst of worry, it was hard to feel the elation I wanted to feel about my book. (She ended up being safe and evacuating within a few days). Then, when Diane and I were working out last edits and cover design, my dog died. I had to take off some time before getting my head back into poetry business.

But the most devastating event was that Chris, my life partner died of an unexpected heart attack on December 2, 2017, a month before the book was to be released. He believed in me, and—not totally understanding how competitive the poetry world is—thought I was going to become famous. That faith in my work buoys me up as I try to find the energy to promote the book. He appears in a few of the poems, and I’m glad of that, but the release of the book (moved to February 2018) is bittersweet. I find it interesting that these traumatic events came about during this time, because through my poetry, I try to understand the balance of life, with its joys and griefs and interconnectedness.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

You’ll laugh, you’ll cry. It’s poetry you can understand and relate to.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Yes, I’ve been reading older novels like Moby Dick and The Great Gatsby and marking passages that are especially poetic (Moby Dick is now marked on almost every page). I also find that classical music inspires me to write poetry.

What are you working on now?

With Chris’s death, I’m obsessed with writing about him. I’m glad I have this form of therapy. I also just wrote a funny/serious poem about trying to live lightly in a heavy world.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Rupert Fike’s new poetry book, Hello the House. It’s funny, and touching, and smart, and so very well written.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Laure-Anne Bosselaar, Mary Oliver, Tom Lux – beyond them, I’d have to list about 10 others.

***

Purchase No Such Thing as Distance .

Karen Paul Holmes has two poetry collections, No Such Thing as Distance (Terrapin, February 2018) and Untying the Knot (Aldrich, 2014). She was named a Best Emerging Poet by Stay Thirsty Media (2016), and publications include Prairie Schooner, Poetry East, Crab Orchard Review, diode, Lascaux Review, and many other journals and anthologies. Holmes founded and hosts a critique group in Atlanta and Writers’ Night Out in the Blue Ridge Mountains. She’s a ballroom dancer, has a Master’s degree in music history from the University of Michigan, and served a long stint as a marketing communications executive in corporate America. Visit her online at www.karenpaulholmes.com.

Karen Paul Holmes has two poetry collections, No Such Thing as Distance (Terrapin, February 2018) and Untying the Knot (Aldrich, 2014). She was named a Best Emerging Poet by Stay Thirsty Media (2016), and publications include Prairie Schooner, Poetry East, Crab Orchard Review, diode, Lascaux Review, and many other journals and anthologies. Holmes founded and hosts a critique group in Atlanta and Writers’ Night Out in the Blue Ridge Mountains. She’s a ballroom dancer, has a Master’s degree in music history from the University of Michigan, and served a long stint as a marketing communications executive in corporate America. Visit her online at www.karenpaulholmes.com.

Published on February 07, 2018 10:46

January 9, 2018

CARPE NOCTEM INTERVIEW: CHRISTINE STODDARD

Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

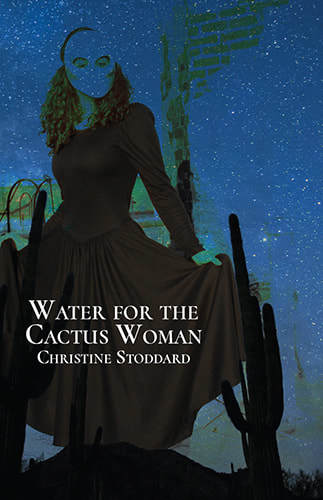

Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I came up with the title because the book is so much about female desire and the many ways society doesn’t quench our thirst. As for cover image, I made it! Water for the Cactus Woman is a full-length collection of poetry and photo collage illustrations. So, all my words and my visuals. I actually made it before the book was fully formed, but when it came to perusing my pre-existing body of work, I felt like only three images really fit. This was my favorite.

Three words: womanhood, questioning, wounds.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create? Who lives in it?

I really wanted to explore my varied identities and challenges as a woman in a way that both felt diary-like and universal. None of the book’s characters are me, per se, but we definitely share things in common. Too many books still present a narrow idea of what it means to be a woman. Often that woman is white, heterosexual, middle class (or higher), college-educated, American-born with American parents, Protestant, and healthy. Some of my characters share aspects of this normalized identity, but they also exist outside of it and show alternatives to it, while still asserting themselves as women whose feelings matter.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I strongly believe in “word vomits,” as I call them. Pour everything onto the page. Revise later. My first drafts are really about my gut. My revisions are more about structure and critical thinking. I tend to revise in isolation. I’ll listen to instrumental music that puts me in a contemplative mood and drink plenty of Bustelo.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I started in a haphazard fashion and then kept re-reading and re-arranging until I thought I had the right flow. Choosing my images and placing them definitely affected the order, too. I did some printing, but mainly arranged the manuscript on my laptop.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

Vulnerability. Storytelling. Beautiful or innovative language.

What’s one of the more crucial poems in the book for you? (Or what’s your favorite poem?) Why? How did the poem come to be? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book, or somewhere else in the process?

That would be “The Portrait Among Marigolds,” which appeared in Amazon.com’s official and now defunct literary magazine, Day One . It’s also in my chapbook, Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares (Semiperfect Press). It’s about family lore, the relationship between mothers and daughters, the pain of womanhood, and the reconciling of identities from the “old country” and the “new country” that all children of immigrants experience. The poem came to be partially from family lore, partially because of this new story I embarked on for the chapbook. I wrote it specifically for the chapbook and later selected it for Water for the Cactus Woman because I felt it matched the tone and content of the full-length book.

Tell us something about the most difficult thing you encountered in this book’s journey. And/or the most wonderful?

This was my first full-length poetry book. It was also my first book that incorporated all of my own original images. (There’s some of my original photography in my nonfiction history book, Hispanic and Latino Heritage in Virginia , but it also includes photos by my sister Helen Georgia Stoddard, as well as archival photography.) Choosing the images for the book was both the most difficult and wonderful part of birthing this book. In this particular case, I chose from my library of already-made images. I didn’t make images specifically for these poems or this collection. Sometimes I’m in the same headspace when I write as I am when I make visual art. Sometimes I’m not. It was really fascinating (and challenging!) for me to figure out what images worked with which poems.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Yo, want to read a book about diverse women coming to terms with their fairly universal issues and get some surreal photo collage illustrations in the mix? I’ve got something for you!

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a poet is to tell a story with your heart. That’s what scares me about being a writer—being so vulnerable. Experimenting with language gives me the most pleasure, but revealing something of myself and human nature is even more important.

I’ve heard poets say they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you? If not, what obsessions or concerns reoccur in your work?

I go through phases. All of my chapbooks and mini poetry books from late 2016 and 2017 (which were titles I mostly wrote in 2014-2016) focus on racial, ethnic, and/or female identity in one way or another. There are definitely some overlapping narrative arcs.

Here’s the lineup:

• Lavinia Moves to New York (Underground Voices)

• Ova (Dancing Girl Press)

• Chica/Mujer (Locofo Chaps)

• The Eating Games (Scars Publications) – Available online for free!

• Jaguar in the Cotton Field (Another New Calligraphy)

• Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares (Semiperfect Press)

• Harlem Mestiza (Maverick Duck Press)

• My Mother’s Pantsuit (Poems-For-All series)

• Frozen (Poems-For-All series)

• Crown Heights (Poems-For-All series)

• Naomi and the Reckoning (Accepted in 2017. Forthcoming from About Editions, formerly Black Magic Media. The title has a very limited web presence right now, so you won’t find a summary for it anywhere online. It’s a novelette with some poetry thrown in there. The story is about a young Southern, Catholic woman with a facial deformity who feels guilty about having sex, even after she’s married.)

I even thought that my other forthcoming full-length, Belladonna Magic (Shanti Arts Publishing; no online presence for the book yet, but it was accepted in 2017), wasn’t political. That lasted all of two seconds. This poetry and photo collage collection is about womanhood and nature. It’s not all pretty and flowery, though. Mother Earth gets raw. And why shouldn’t she? Climate change is real.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

Yes, poets do have that responsibility, but it doesn’t always have to be pre-meditated. As a poet, you internalize so much. That extends to politics and social issues. We live in a world saturated by politics and socio-economic challenges. Politics touch even our most mundane choices and experiences. What we eat is a political choice—and when we have no food because of poverty and lack of access, that’s a political matter, too. What we wear is a political choice, especially if you’re a woman, a gender non-conforming person, and/or an ethnic or religious minority whose culture requires distinctive dress.

My work does address social issues, especially those related to women’s rights, race relations, cultural identity, and religious tensions. My personal identity and upbringing made me aware of peace and conflict resolution at a young age. I grew up in a predominantly white, upper middle class suburb outside of Washington, D.C., but my family didn’t quite fit into our neighborhood. My mother, who is a Salvadoran immigrant and cradle Catholic, was often confused for my “Mexican” nanny. She was a fairly traditional housewife, whereas many of my classmates’ mothers were career women. My father, a white, native New Yorker, spent much of his early life in a blue-collar environment. While he did graduate from a fine art school and later a university with a top-rated photography program, he didn’t share an alma mater in common with the other parents, who all mostly attended the same schools. He worked very hard as a cameraman for national television and made an excellent living. But we lived in a neighborhood where most families had both parents working very good jobs, not just one. As such, my mother scrimped and saved to make sure we stayed there, mostly for the nationally ranked public schools.

Just in that brief peek into my childhood, you can see how my touching on topics like immigration, race, education, social class, and religion would be inevitable. Sometimes I explicitly mention political figures or events in my work. When I don’t, politics come out, anyway.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Yes! Definitely. I really do read widely. As my friend and fellow poet Mari Pack says, we know a lot about the “borders” of many things because of it, but we’re generalists for that very reason. Right now I’m in grad school for digital and interdisciplinary art, so I’m reading a lot of digital media history, theory, and criticism. Sub-topics include cybernetics, online privacy, bio art, the New Aesthetic Movement, and the culture of surveillance. My M.F.A. is visually oriented, but it requires a lot of reading and non-fiction writing that’s grounded in relevant history and theory.

I’m also doing a fair amount of career reading, especially as it pertains to writing grant, residency, and scholarship proposals. LinkedIn articles are my daily go-to, but I’ll seek out career books, too. That sort of reading influences my creative writing (often in a mocking or critical way because I have big problems with so-called “meritocracy”), but it also helps me learn how to get opportunities to write. For instance, last summer I was the visiting artist at the Annmarie Sculpture Garden, a Smithsonian affiliate in Maryland. I made 11 sculptures as part of a public art project and worked extensively on my private projects, which definitely included poetry. Scoring that residency relied heavily on knowing how to craft a convincing proposal. Once I was selected, I had the time and space to create. Such an opportunity is precious.

What are you working on now?

Right now I’m finishing the long process of revising my novel, Moon Fish. Every once in a while, I will divert myself with other projects. The main diversion is my novel, Conejita, which isn’t as far along as Moon Fish. I’m also adapting my chapbook, Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares (Semiperfect Press, 2017), into a stage play and creating visuals for my full-length collection, Lust at Tea. Last but not least, I’m sending my chapbook, Clam Ear, out into the world and waiting to hear back on my full-length collection, Desert Fox by the Sea.

Favorite places and times of day or night to work?

I’m a night owl by nature, but my daily life doesn’t always allow for that schedule. When I do get to stay up late, I love to work at my kitchen table. It’s a hand-me-down from my husband’s grandmother. Because my husband and I live in a small Brooklyn apartment, the kitchen table practically kisses our piano. It’s a cozy space. On a normal weekday, I’m generally on campus at the City College of New York in Harlem, where I languish in my art studio. On the days I work from home, I love pulling my laptop into my canopy bed and burying myself under several blankets. I’m all for comfort.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

The Selfishness of Others: An Essay on the Fear of Narcissism by Kristin Dombek

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

1. Gwendolyn Brooks

2. Nikki Giovanni

3. Sylvia Plath

4. Maya Angelou

5. Ada Limón

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Who do you go to for love and support when writing and art-making get lonely? My husband, David. Every ship needs a harbor and he is mine.

***

Order Water for the Cactus Woman.

Christine Stoddard is a former Annmarie Sculpture Garden artist-in-residence, a Puffin Foundation emerging artist, and an M.F.A. DIAP candidate at the City College of New York (CUNY). Her work has appeared in special programs at venues like the New York Transit Museum and the Queens Museum, as well as publications like The Feminist Wire, Bustle, Marie Claire, The Huffington Post, and beyond. She is also the author of Water for the Cactus Woman (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing), among other titles, and the founder of

Quail Bell Magazine

. This summer, she will be a visiting artist at Laberinto Projects in El Salvador.

Christine Stoddard is a former Annmarie Sculpture Garden artist-in-residence, a Puffin Foundation emerging artist, and an M.F.A. DIAP candidate at the City College of New York (CUNY). Her work has appeared in special programs at venues like the New York Transit Museum and the Queens Museum, as well as publications like The Feminist Wire, Bustle, Marie Claire, The Huffington Post, and beyond. She is also the author of Water for the Cactus Woman (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing), among other titles, and the founder of

Quail Bell Magazine

. This summer, she will be a visiting artist at Laberinto Projects in El Salvador.

Published on January 09, 2018 07:29

January 2, 2018

Carpe Noctem Interview: Lesléa NEWMAN

Headmistress Press, 2018

Lovely

follows I Carry My Mother, in which you elegize your mother, Florence Newman, and trace your grieving process as you simultaneously celebrate her life. What theme or group of poems sparked Lovely for you, and how do you see it being related to or a continuation of I Carry My Mother?

Headmistress Press, 2018

Lovely

follows I Carry My Mother, in which you elegize your mother, Florence Newman, and trace your grieving process as you simultaneously celebrate her life. What theme or group of poems sparked Lovely for you, and how do you see it being related to or a continuation of I Carry My Mother?I am constantly writing poems, so after about two years had gone by since the publication of I Carry My Mother, I decided to look at what I had to see if a collection might take shape. I was surprised that there were so many poems about my mom; I thought I was done writing about her. I now see (and it should have been obvious) that I will never be done writing about her. And I am grateful for that. Other themes that emerged were childhood memories, aging, political poems, and love poems. This book is different than past poetry collections of mine such as I Carry My Mother, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard, and Still Life with Buddy each of which tells a cohesive story from beginning to end. Lovely is broken up into sections, and each section has a different theme.

Nostalgia’s hard at work in this collection, as you reflect on your childhood in New York City and your relationship with your mother, both as you’re growing up and growing older. Since we can’t return to all the homes in our memories, we often feel a longing for those spaces, even those that were imperfect. In “The Chanukah Game,” I love these lines that embody the realization of the passage of times as our lives run out: “Whose flame will last the longest?// Fifty years flicker by./ My Persian cat turns twenty.” What sort of longing or desire to return to your past and to your family of origin compelled these poems? Is the role nostalgia plays in your poems now different than when you were younger?

As I was writing this book, I was caring for my father, who died on December 12, 2017. I was acutely aware of the fact that he was 90 and at the end of his life. During this time, I moved him from my childhood home into independent living; the house was sold and torn down. It was the end of an era. As a child, I watched that house being built. Because it has now been torn down, we are the only family that ever lived in it. Going through my parents’ possessions was very emotional, as my dad had to downsize from a four bedroom house to a one-bedroom apartment. So yes, I was longing to return to a time when my family was intact, and when I was young and innocent and protected. I think I long for that now more than ever, as I adjust to live on this planet with both my parents gone.

In “Home Safe,” the young narrator is sexually assaulted by a neighborhood boy. In “First Death,” the narrator experiences her first death, of a young female friend, and doesn’t quite grasp the solemnity of it. “In Sleepaway Camp, 1969,” the narrator relives kissing a young African-American boy in secret at night. Talk about what you wanted to convey about childhood in Lovely – are there any lessons learned or certain way of seeing you wanted to share specifically with readers?

I wanted to explore these and other events with the perspective of looking back, in some cases, half a century later. I feel more compassion now for the child and teen I was. I was not a “happy camper” for much of my young life and now, looking back, I can see why. There is no one to blame for my teenage malcontent. Everyone did the best that they could. I feel more compassion for myself and others, as I realize that everyone has burdens to bear. I hope some of the poems convey that.

The gorgeous prose poem “Maidel” (along with poems like “The Price” and “My Mother’s Stories”) is a collection of cliché motherly admonitions: “I ate nothing but Tums when I was pregnant with you. Boys are easier to raise than girls. Just wait till you have a daughter. But Mom, I don’t want to have children.” This is juxtaposed with tender poems like “My Mother Cups Her Hand”: “My mother cups her hand around my cheek/ And draws me close until we’re head to head // We know that she’ll be dead within a week.” The mother-daughter relationship is so complex, especially as the daughter turns to caregiver for her aging and dying mother. Is there a catharsis or unburdening in writing these two types of mother poems?

I love writing about my mother because it brings her close to me. Since I often write in her voice, it’s like she’s sitting on my shoulder, whispering in my ear. And I love giving readings that feature these poems, because I get to hear her words through my own voice and share her with others. It’s funny, things she said that angered me at the time, such as “I’m cold, go put on a sweater” amuse me now. I don’t know about a catharsis, but I do know writing poems about my mother makes me very happy. It’s almost like dreaming about her, which I consider a visitation.

I loved your tiny, hard-hitting poem, “Old Age,” that reads in its entirety:

“The cat, so afraid of an ice cube’s sharp clink,

Now stirs not a hair as I mix a stiff drink.”

This joins other poems in which the narrator contemplates a bristly chin whisker at age 61, watching her brother’s baby son turn into a man, watching her Persian cat turn 20, contemplating how weeds survive despite their outcast status, “they believe in their wild and glorious beauty” and “they can weather any and every storm.” You write about aging with grace and humor, without being cliché or depressing. How does growing older inform your work now?

Well, I have become a “woman of a certain age,” that certain age being 62. Which feels different, now that both my parents are gone. I really thought I would remain young forever! As a young woman, I received, for better or for worse, a certain amount of attention because of my appearance, sometimes wanted, sometimes unwanted. It’s interesting to now be invisible in certain ways. This is somewhat of a relief, and at the same time, something to adjust to. It’s interesting to watch my body change, to watch the changing ways others relate to me now that I am in my sixties, to watch my own response to my changing reflection in the mirror, and to watch how my friends change as they age as well. This is very rich material to explore in poetry!

In “1955-2001: A Hair Odyssey,” the narrator says, “The first thing I do/ when I realize I am a lesbian/ is hack off my hair./ The second thing I do/ is cry.” You’ve included poems that address the experience of being gay in America, like “That Night,” memorializing the victims of the June 2016 shooting in an Orlando nightclub and “Teen Angels,” where you remember six victims of gay hate crimes. If a young, gay person (and/or poet) reads this book, what do you want to tell them about how this part of their identity will inform their lives? Is there hope for a future where they don’t have to fear being beaten or killed for being gay?

I am always hopeful that the world will become a safer place for all of us, and a big part of that hope stems from interacting with young people who are working so hard to make this happen. I am constantly inspired by their dedication, passion, outrage, and commitment to social justice. I hope that the love poems in the collection, which mostly center on my 30-year relationship with my beloved, provide a balance with the poems about violence against LGBTQ+ people and show that our lives are possible, despite the odds stacked against us.

This book is also an exuberant celebration of same-sex love and a long life partnership. These poems stood out to me as being especially resonant: “Your Loss: To the Lovely Butch In Front Of Me At The A&P,” “Paradise Found,” “Night On The Town” and “Ghazal For My Beloved.” Tell me what the job of a love poem is, and how do you write one that covers new territory?

It is so hard to write a love poem that is original and new. Love is a universal theme and yet each person’s love is unique. So that is what I see as the job of a love poem: to speak to the common experience of all of us and yet be specific and communicate what is unique about the love between the two particular people featured in the poem. As Jack Kerouac so famously said, “Details are the life of the novel.” They are the life of the poem—particularly the love poem—as well.

As in I Carry My Mother, you take inspiration from other poets like Wallace Stevens (his “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” becomes “Thirteen Ways of Looking at My Mother” in I Carry My Mother and “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackboard” and “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Poet” in Lovely), William Carlos Williams and Elizabeth Bishop – and make their poems/poetic forms new. What attracts you to doing this, and how did you choose which poets/poems to honor this way?

I love writing imitations and am so glad that this is seen as a legitimate form. In I Carry My Mother, many of the poems I chose to imitate were favorites of my mom. In Lovely, my process was a bit different. “Thirteen Ways of Looking At A Blackboard” actually came about because of a typo! Other poems such as “The Span of Life” by Robert Frost upon which “Old Age” is based and “The Walrus And The Carpenter” by Lewis Carroll upon which “The Writer And The Messenger” is based were chosen because of my great admiration for them.

We’ve talked about this before, that many of your poems are written in rhymed stanzas, with some in more traditional formats like ghazals, triolets and villanelles. You even create your own forms, as with “My Mother’s Stories,” where you create a compelling portrait out of soap opera titles. Please talk about your prosody – what draws you to these forms specifically?

I love writing in form. I find it very challenging and very satisfying. It’s a good way to exercise my poetry muscles. I don’t understand why more poets don’t write in form. Why wouldn’t I turn to forms that are centuries old and that were and are still being employed by poets with far more experience and talent than I (Shakespeare! Marilyn Hacker! Stanley Kunitz! Marilyn Nelson!) Writing in form takes a certain type of concentration and really forces me as a poet to look at every single word in a poem and make sure each choice is absolutely perfect. The forms I use often use rhyme and repetition and I find the tension between the predictable pattern and the unpredictable variation of the pattern a wonderful balance.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Ordering the poems is very challenging. It is not haphazard at all. I look for ways the poems speak to each other and my hope is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, in that the result is this group of poems in this specific order sparks a conversation between poet and reader.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The poem “Between Flights” is a poem that inspired the title Lovely, as readers will see. It encompasses many of the themes of the book: aging, loss, standards of female beauty, nostalgia, etc. I think it is very close to the heart of the book and was actually written in an airport (or more accurately, the first draft was written in an aiport; each poem of mine goes through between 10 and 20 drafts or more).

BETWEEN FLIGHTS

“I knew a woman, lovely in her bones”

--Theodore Roethke

And so I name them Lovely and Lovelier

these two young beauties sitting before me

at the airport, the older one braiding

the younger one’s hair. Lovely is perched

on the edge of womanhood as surely

as she is perched on the edge

of her black vinyl seat, lost

in concentration as she combs

her fingers through Lovelier’s hair

separating it into several hanks

and holding them aloft like the reins

of a filly who has consented to be tamed.

Lovelier kneels on the floor

back straight and neck elongated

like a Modigliani model

a Mona Lisa smile playing

across her glossy lips.

Or perhaps I am wrong.

Perhaps the older one is Lovelier

her elegant arms drifting up and down

like a principle dancer

as she weaves Lovely’s hair

into an intricate French braid

too stylish for her young

face which still boasts freckles

across her nose like the spots

of a doe too small to leave her mother.

And now the braid is done

and the younger girl lifts

one hand to the side of her head

patting it gently to make sure

it is perfect as she is perfect,

and the older girl sits back

to admire the good work she has done,

and I, who was once just as lovely

if not lovelier than the two of them

put together, sally forth

toward my own gate as they rise

and fly past me to soar into their lives.

Can you share any wisdom you’ve learned during your prolific career with young women writers that you wish you had known when you were starting out?

Write every day. Read as much as possible. Find or start a writers group with other poets who will be honest with you about your work. Revise, revise, revise. When you send your work out, don’t “submit” it. “Offer” it. That way it can never be “rejected.” It can be “accepted” or “declined.” Above all else, be kind to other writers. When any one of us succeeds, all of us succeeds.

***

Order Lovely.

Photo by Mary Vazquez Lesléa Newman is the author of 70 books for readers of all ages including the poetry collections, Still Life with Buddy, Nobody’s Mother, and Signs of Love, and the novel-in-verse, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard. Newman has received many literary awards including poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Artists Foundation, and a Stonewall Honor from the American Library Association. Her poetry has been published in Spoon River Poetry Review, Cimarron Review, Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, Evergreen Chronicles, Harvard Gay and Lesbian Review, Lilith Magazine, Kalliope, The Sun, Bark Magazine, Sow’s Ear Poetry Review, Seventeen Magazine and others. Nine of her books have been Lambda Literary Award Finalists. From 2008-2010 she served as the poet laureate of Northampton, MA. Currently she lives in Holyoke, MA and is a faculty member of Spalding University’s low-residency MFA in Writing program. Visit her online at http://www.lesleanewman.com.

Photo by Mary Vazquez Lesléa Newman is the author of 70 books for readers of all ages including the poetry collections, Still Life with Buddy, Nobody’s Mother, and Signs of Love, and the novel-in-verse, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard. Newman has received many literary awards including poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Artists Foundation, and a Stonewall Honor from the American Library Association. Her poetry has been published in Spoon River Poetry Review, Cimarron Review, Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, Evergreen Chronicles, Harvard Gay and Lesbian Review, Lilith Magazine, Kalliope, The Sun, Bark Magazine, Sow’s Ear Poetry Review, Seventeen Magazine and others. Nine of her books have been Lambda Literary Award Finalists. From 2008-2010 she served as the poet laureate of Northampton, MA. Currently she lives in Holyoke, MA and is a faculty member of Spalding University’s low-residency MFA in Writing program. Visit her online at http://www.lesleanewman.com.

Published on January 02, 2018 08:51

November 12, 2017

carpe noctem interview: susanna lang

Terrapin Books, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Terrapin Books, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

My first attempt to brainstorm titles was embarrassing, now that I look back at it. But once I wrote the poem that would become the opening to the collection, I knew the book would be structured as a journey, and my next list was much more promising. I settled on “Travelers,” wanting to convey the idea that we are all traveling together, as pilgrims do. Diane Lockward at Terrapin Books worried that the title would not grab readers’ attention, and we agreed on “Travel Notes from the River Styx” (the title of a poem in the book) to retain the idea of travel. Many of the poems are elegiac, so the title’s emphasis on the last journey seemed appropriate, though I hope the book is more expansive than that.

The cover image is a river photograph by Nancy Marshall, an artist who was on residency at Hambidge in the Blue Ridge Mountains at the same time I was. She uses old technologies in her photographs, which are typically black-and-white or sepia. Diane thought that a black-and-white photo would be invisible in a bookstore, but color images seemed garish for these poems, or touristy. Another friend who is both a photographer and a writer, Pat Daneman, experimented with a blue filter. I love the resulting cover, which has the right tonality for the book without melting into the background.

Three words: Journey, elegy, witness

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I rarely write books as projects, with each new poem fitting into the scheme. I’ve really only done it once, with a chapbook of ekphrastic poems that is still an ongoing project and that focuses on women’s art. Usually, I let poems come to me and then step back every few years to explore what images and themes or forms have been dominant in my work over that period. Once the collection begins to take shape, accepting some poems and excluding others, I can see gaps where I need to write for a specific moment in the sequence.

In terms of revision, I read the poem (or the collection) aloud and reread and carry it around in my head till I can’t do anything more with it—and then I get as much feedback as I can, from as many readers as I can. I find that the solutions my readers propose are often wrong, but their comments point me to the problems I need to resolve in my own way, and my best readers point me in the right direction to find those solutions.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

One of the many joys of Hambidge Creative Residency Center is that every studio has a corkboard wall or two, with ample pushpins: I can pin the poems up in a sequence and live with that sequence, eating my meals with the poems and moving them around as I see the need. Nikky Finney told me that she tapes poems up and down the staircase in her house. Hard on the paint, but I like that idea, too.

Because I thought of this collection as a journey, and because my usual habit of mind is linear, the sequence of this book was linear in the beginning. Diane asked me to rethink it as a braid. That was a difficult task for me, but I discovered an old cork board of my son’s in the attic and set to work over an intense period of revision last spring. I found that I had to quiet my conscious, analytic mind and work almost in a dream state, without articulating clearly why one poem belongs with the other, but intuiting they needed to be together. The result is satisfying to both my publisher and me, but I don’t know if I could do it again—it'll be interesting to see what happens next time.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love what Ellen Bass calls a “long-armed poem,” a poem that can embrace disparate elements and make them part of an organic whole. Think Walt Whitman, but also Kevin Prufer—and of course Ellen Bass herself.

I care enormously about craft, that each word choice, each punctuation mark, the length and music of the line all are intentional and effective without necessarily calling attention to themselves. Rather, you have to deliberately study the architecture and sound systems of the poem in order to see how it’s put together, after the first read sucks you in and seduces you.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The opening poem, “Road Trip,” is the one poem that was specifically written for this collection and for this position in the collection: it is the elegy I wrote after my father’s death, a loss that is at the heart of the book. It's one of my own “long-armed poems.” However, the poem is itself long, and perhaps more easily read when you are holding the book in your hand (I am old-fashioned about books). The journey ends with two short poems, one of which has the title I originally wanted for the book, “Traveler.” It is a response to a 5,000-year-old figure that stands at the entrance to the Mesopotamian gallery in the Art Institute of Chicago, very finely crafted despite its great age:

Traveler

Striding Horned Figure, Mesopotamia, ca. 3000 B.C.

You, hawk-

shouldered and

silent, you lead the way

between this world and another.

You slip

between fog

and water. You come and

go again, boots curled back over

your toes,

copper-tongued,

unspeaking. Teach us to

count and to lose track, to climb and

descend--

you, goat-eared

and wide-eyed, show us how

you cross the fiery bridge, how you

steer us

and how you

stay behind when we have

all gone down, gone all the way down.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

I am not a good salesperson….

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

Writing is so many things for me, but perhaps most of all a way of living, open to the world and to others in the world, attuned to language. I am a public school teacher and I have to get up much earlier than I want to, in order to write before I leave for school. Teaching is too intense to leave me with the energy to write in the evenings—not to mention the papers that need to be graded and the lessons planned before the next day! But that sacred time in the early morning launches me into my day and makes me ready for everything else that I will encounter.

Writing is a way to make sense of the world and of my place in it, a way to make beauty for others as well as for myself. I have found a community with other writers who care about the same things I do, and I am a better teacher because what I teach is not a subject for me but a discipline, in every sense of that word, and a passion.

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you? If not, what are your obsessions that reoccur in your work?

Charles Wright said in a workshop I attended that we all have nine images that we return to again and again. I don’t know where he got the number nine, but I think writers are easily haunted by images, or by words. Rivers call to me, so bridges do too. A word like “lacuna” can send me to my notebook. My father had a long, slow, painful decline before his death in May 2015, just before I put this book together, and in that time I lost other loved ones to quicker deaths, so it’s not surprising that the book is elegiac. The obsessions change over the years: In my first book, for some reason it was geese, until my husband and my writing friends convinced me that I had said what there was to say about geese.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

I think that all humans have a responsibility to respond in whatever way they can to what’s happening in the world, so writers and artists have a responsibility to use their art as a platform from which to respond. Like many others, I am writing more overtly political poems since the presidential election last year, but all my books include some justice poems. For Travel Notes, I chose poems—all written before the 2016 election—that respond to the Japanese tsunami of 2011 and the debris that rode across the ocean, to the wars in Syria and the upheaval in Ukraine, to the eerie echoes of Anna Akhmatova’s Russia in our own current situation, the Arab spring, and conflict in Israel and Palestine, as well as the church shooting in Charleston and my own students’ challenges.

I'm a news junkie, more so now than ever though it’s painful to stay aware and many of my friends are talking about giving themselves permission to turn away. I believe that we must not turn away, that this is no time to cultivate our own gardens or to do so exclusively. Of course, we need to stay sane and healthy, too, in order to have the energy to fight back. Poetry is what keeps me sane, and at the same time gives me a way to resist. I do not agree with Shelley that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world, but we can be the world’s conscience—and then we need to go out with our friends and neighbors and march in the streets and vote like everyone else, so that the legislators we send to our capitols give us the right laws.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I often write from what I know is going on in the world, so National Public Radio, the New York Times, the Washington Post are all daily reading and listening that feed my writing. I also read fiction but that reading is either for my classes or for fun and rarely connects with my writing. The other arts do, though, especially music (classical and jazz for the most part, though the opening poem in my book quotes a lyric by Carla Bruni) and the visual arts.

What are you working on now?

I have an ongoing project, a chapbook manuscript of ekphrastic poems focused on women’s art. That collection also grew out of my time at Hambidge, where I assembled Travel Notes. During my second week there, all the residents were women, writers and artists, and dinner conversation often turned to the experience of creating art as a woman. You need only look at the count published by VIDA: Women in Literary Arts to see that women are underrepresented in publications and reviews, and similar counts have been made for museums and galleries. I wanted to celebrate women’s art, and to open a virtual gallery of works that especially move me. Beyond that celebration, I wanted to explore the ways in which our art, even when it is not literally a portrait of our bodies or a retelling of our lives, becomes the way in which we recreate ourselves.

In addition to the ekphrastic poems, I am doing what I always do after I finish a big collection: writing what comes to me, without worrying too much about the direction in which the poems lead me.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I spent a lot of time this summer with W. S. Merwin’s poetry, which is so humane and so hauntingly beautiful, especially in recent years. Summers are when I can read poetry intensively; during the school year, my reading is more scattershot. Summer 2016 it was Peter Balakian. In 2015, when I was putting this book together, Kevin Prufer, Mark Doty and Tracy K. Smith. I prefer to read multiple books by a writer and really immerse myself in that voice.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Sappho

Lucille Clifton

Walt Whitman

William Butler Yeats

Mark Doty

***

Purchase Travel Notes from the River Styx.