CARPE NOCTEM INTERVIEW: CHRISTINE STODDARD

Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

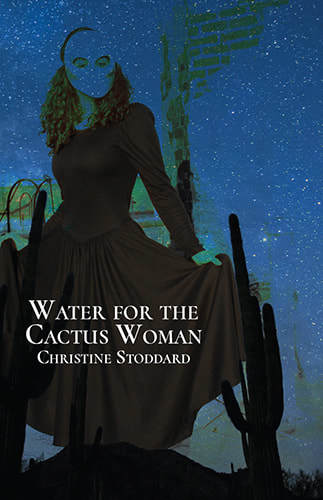

Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, 2018 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I came up with the title because the book is so much about female desire and the many ways society doesn’t quench our thirst. As for cover image, I made it! Water for the Cactus Woman is a full-length collection of poetry and photo collage illustrations. So, all my words and my visuals. I actually made it before the book was fully formed, but when it came to perusing my pre-existing body of work, I felt like only three images really fit. This was my favorite.

Three words: womanhood, questioning, wounds.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create? Who lives in it?

I really wanted to explore my varied identities and challenges as a woman in a way that both felt diary-like and universal. None of the book’s characters are me, per se, but we definitely share things in common. Too many books still present a narrow idea of what it means to be a woman. Often that woman is white, heterosexual, middle class (or higher), college-educated, American-born with American parents, Protestant, and healthy. Some of my characters share aspects of this normalized identity, but they also exist outside of it and show alternatives to it, while still asserting themselves as women whose feelings matter.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I strongly believe in “word vomits,” as I call them. Pour everything onto the page. Revise later. My first drafts are really about my gut. My revisions are more about structure and critical thinking. I tend to revise in isolation. I’ll listen to instrumental music that puts me in a contemplative mood and drink plenty of Bustelo.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I started in a haphazard fashion and then kept re-reading and re-arranging until I thought I had the right flow. Choosing my images and placing them definitely affected the order, too. I did some printing, but mainly arranged the manuscript on my laptop.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

Vulnerability. Storytelling. Beautiful or innovative language.

What’s one of the more crucial poems in the book for you? (Or what’s your favorite poem?) Why? How did the poem come to be? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book, or somewhere else in the process?

That would be “The Portrait Among Marigolds,” which appeared in Amazon.com’s official and now defunct literary magazine, Day One . It’s also in my chapbook, Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares (Semiperfect Press). It’s about family lore, the relationship between mothers and daughters, the pain of womanhood, and the reconciling of identities from the “old country” and the “new country” that all children of immigrants experience. The poem came to be partially from family lore, partially because of this new story I embarked on for the chapbook. I wrote it specifically for the chapbook and later selected it for Water for the Cactus Woman because I felt it matched the tone and content of the full-length book.

Tell us something about the most difficult thing you encountered in this book’s journey. And/or the most wonderful?

This was my first full-length poetry book. It was also my first book that incorporated all of my own original images. (There’s some of my original photography in my nonfiction history book, Hispanic and Latino Heritage in Virginia , but it also includes photos by my sister Helen Georgia Stoddard, as well as archival photography.) Choosing the images for the book was both the most difficult and wonderful part of birthing this book. In this particular case, I chose from my library of already-made images. I didn’t make images specifically for these poems or this collection. Sometimes I’m in the same headspace when I write as I am when I make visual art. Sometimes I’m not. It was really fascinating (and challenging!) for me to figure out what images worked with which poems.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Yo, want to read a book about diverse women coming to terms with their fairly universal issues and get some surreal photo collage illustrations in the mix? I’ve got something for you!

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a poet is to tell a story with your heart. That’s what scares me about being a writer—being so vulnerable. Experimenting with language gives me the most pleasure, but revealing something of myself and human nature is even more important.

I’ve heard poets say they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you? If not, what obsessions or concerns reoccur in your work?

I go through phases. All of my chapbooks and mini poetry books from late 2016 and 2017 (which were titles I mostly wrote in 2014-2016) focus on racial, ethnic, and/or female identity in one way or another. There are definitely some overlapping narrative arcs.

Here’s the lineup:

• Lavinia Moves to New York (Underground Voices)

• Ova (Dancing Girl Press)

• Chica/Mujer (Locofo Chaps)

• The Eating Games (Scars Publications) – Available online for free!

• Jaguar in the Cotton Field (Another New Calligraphy)

• Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares (Semiperfect Press)

• Harlem Mestiza (Maverick Duck Press)

• My Mother’s Pantsuit (Poems-For-All series)

• Frozen (Poems-For-All series)

• Crown Heights (Poems-For-All series)

• Naomi and the Reckoning (Accepted in 2017. Forthcoming from About Editions, formerly Black Magic Media. The title has a very limited web presence right now, so you won’t find a summary for it anywhere online. It’s a novelette with some poetry thrown in there. The story is about a young Southern, Catholic woman with a facial deformity who feels guilty about having sex, even after she’s married.)

I even thought that my other forthcoming full-length, Belladonna Magic (Shanti Arts Publishing; no online presence for the book yet, but it was accepted in 2017), wasn’t political. That lasted all of two seconds. This poetry and photo collage collection is about womanhood and nature. It’s not all pretty and flowery, though. Mother Earth gets raw. And why shouldn’t she? Climate change is real.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

Yes, poets do have that responsibility, but it doesn’t always have to be pre-meditated. As a poet, you internalize so much. That extends to politics and social issues. We live in a world saturated by politics and socio-economic challenges. Politics touch even our most mundane choices and experiences. What we eat is a political choice—and when we have no food because of poverty and lack of access, that’s a political matter, too. What we wear is a political choice, especially if you’re a woman, a gender non-conforming person, and/or an ethnic or religious minority whose culture requires distinctive dress.

My work does address social issues, especially those related to women’s rights, race relations, cultural identity, and religious tensions. My personal identity and upbringing made me aware of peace and conflict resolution at a young age. I grew up in a predominantly white, upper middle class suburb outside of Washington, D.C., but my family didn’t quite fit into our neighborhood. My mother, who is a Salvadoran immigrant and cradle Catholic, was often confused for my “Mexican” nanny. She was a fairly traditional housewife, whereas many of my classmates’ mothers were career women. My father, a white, native New Yorker, spent much of his early life in a blue-collar environment. While he did graduate from a fine art school and later a university with a top-rated photography program, he didn’t share an alma mater in common with the other parents, who all mostly attended the same schools. He worked very hard as a cameraman for national television and made an excellent living. But we lived in a neighborhood where most families had both parents working very good jobs, not just one. As such, my mother scrimped and saved to make sure we stayed there, mostly for the nationally ranked public schools.

Just in that brief peek into my childhood, you can see how my touching on topics like immigration, race, education, social class, and religion would be inevitable. Sometimes I explicitly mention political figures or events in my work. When I don’t, politics come out, anyway.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Yes! Definitely. I really do read widely. As my friend and fellow poet Mari Pack says, we know a lot about the “borders” of many things because of it, but we’re generalists for that very reason. Right now I’m in grad school for digital and interdisciplinary art, so I’m reading a lot of digital media history, theory, and criticism. Sub-topics include cybernetics, online privacy, bio art, the New Aesthetic Movement, and the culture of surveillance. My M.F.A. is visually oriented, but it requires a lot of reading and non-fiction writing that’s grounded in relevant history and theory.

I’m also doing a fair amount of career reading, especially as it pertains to writing grant, residency, and scholarship proposals. LinkedIn articles are my daily go-to, but I’ll seek out career books, too. That sort of reading influences my creative writing (often in a mocking or critical way because I have big problems with so-called “meritocracy”), but it also helps me learn how to get opportunities to write. For instance, last summer I was the visiting artist at the Annmarie Sculpture Garden, a Smithsonian affiliate in Maryland. I made 11 sculptures as part of a public art project and worked extensively on my private projects, which definitely included poetry. Scoring that residency relied heavily on knowing how to craft a convincing proposal. Once I was selected, I had the time and space to create. Such an opportunity is precious.

What are you working on now?

Right now I’m finishing the long process of revising my novel, Moon Fish. Every once in a while, I will divert myself with other projects. The main diversion is my novel, Conejita, which isn’t as far along as Moon Fish. I’m also adapting my chapbook, Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares (Semiperfect Press, 2017), into a stage play and creating visuals for my full-length collection, Lust at Tea. Last but not least, I’m sending my chapbook, Clam Ear, out into the world and waiting to hear back on my full-length collection, Desert Fox by the Sea.

Favorite places and times of day or night to work?

I’m a night owl by nature, but my daily life doesn’t always allow for that schedule. When I do get to stay up late, I love to work at my kitchen table. It’s a hand-me-down from my husband’s grandmother. Because my husband and I live in a small Brooklyn apartment, the kitchen table practically kisses our piano. It’s a cozy space. On a normal weekday, I’m generally on campus at the City College of New York in Harlem, where I languish in my art studio. On the days I work from home, I love pulling my laptop into my canopy bed and burying myself under several blankets. I’m all for comfort.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

The Selfishness of Others: An Essay on the Fear of Narcissism by Kristin Dombek

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

1. Gwendolyn Brooks

2. Nikki Giovanni

3. Sylvia Plath

4. Maya Angelou

5. Ada Limón

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Who do you go to for love and support when writing and art-making get lonely? My husband, David. Every ship needs a harbor and he is mine.

***

Order Water for the Cactus Woman.

Christine Stoddard is a former Annmarie Sculpture Garden artist-in-residence, a Puffin Foundation emerging artist, and an M.F.A. DIAP candidate at the City College of New York (CUNY). Her work has appeared in special programs at venues like the New York Transit Museum and the Queens Museum, as well as publications like The Feminist Wire, Bustle, Marie Claire, The Huffington Post, and beyond. She is also the author of Water for the Cactus Woman (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing), among other titles, and the founder of

Quail Bell Magazine

. This summer, she will be a visiting artist at Laberinto Projects in El Salvador.

Christine Stoddard is a former Annmarie Sculpture Garden artist-in-residence, a Puffin Foundation emerging artist, and an M.F.A. DIAP candidate at the City College of New York (CUNY). Her work has appeared in special programs at venues like the New York Transit Museum and the Queens Museum, as well as publications like The Feminist Wire, Bustle, Marie Claire, The Huffington Post, and beyond. She is also the author of Water for the Cactus Woman (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing), among other titles, and the founder of

Quail Bell Magazine

. This summer, she will be a visiting artist at Laberinto Projects in El Salvador.

Published on January 09, 2018 07:29

No comments have been added yet.