Nicole Rollender's Blog, page 2

September 28, 2017

CARPE NOCTEM INTERVIEW: Pat Hanahoe-Dosch

FutureCycle Press, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

FutureCycle Press, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The title comes from one of the poems, "The Wrack Line," but it's also a recurring image in the book. A wrack line is the jagged line of detritus - mostly seaweed, broken marsh grasses, shells, algae, and/or driftwood - that runs along a beach after the tide goes out. It's a wonderful metaphor to me for many things. The cover image is actually a very big close-up of a small pool of water on the beach on Absecon Island, NJ, and the edges of it that were cluttered with broken bits of dried reeds, probably a type of marsh grass, which often wash up there. It's not really a wrack line, but it kind of looks like the edge of one, and is such a strong image in its own right, my editor pushed for that one over the photos I had of real wrack lines or the beach. I took the shot one day after a mild storm. My parents live on that island (I grew up there) and I visit it often. It's more home to me than where I currently live. I'm not sure what three words sum up the book - maybe: storms, love, and passage.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create? Who lives in it?

I didn't have a plan or world I wanted to create. The poems evolved over a number of years. I started out writing about Hurricane Sandy and what it did to NJ, but other interests took over. The college where I teach gave me a one semester sabbatical, so I bought a cheap, used mini-van and drove around the country, sleeping in the back of the van or in a tent, trying to write about the places and people I met. In the end, I supposed mostly I was trying to write in the poems about people and places I visited here and abroad - but other things interposed themselves, too, like social concerns and family stuff. But then, those are about people, too.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I have the good luck to belong to a group of people - mostly colleagues from where I teach - who meet once a month to discuss our writing. We critique each others' work. Their advice helps me revise. But I also continuously revise my work - I revise my poems probably close to 50 or more times, on average. Some of the ones in this book I worked on for years.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

This was the hardest part. I'm still not sure I'm satisfied with the order. I never really know how to do that. I re-ordered it about every day for a month, then left it alone and went back to it several months later, again every day for another month. Finally, I left it alone, and came back to it several months later, spread it all out on the floor, and saw it the way it is now. But part of me would like to go back and re-order it again. I tried to arrange it thematically. The sections are all a bit different, even in technique, so they were easy, but arranging the poems within the sections was tough.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

Passion, strong, moving imagery, and precise, interesting diction.

What’s one of the more crucial poems in the book for you? (Or what’s your favorite poem?) Why? How did the poem come to be? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book, or somewhere else in the process?

"Surrender" is probably my favorite poem. It was published in Rattle, and is the one that people seem to respond to the most strongly. Getting published in Rattle felt like a huge accomplishment. I'd been published in a few big magazines before that, and a lot of small ones, but this one not only paid money ($25) for a poem, but was online and reached a huge audience - much larger even than Confrontation or the Paterson Review. It gave me the confidence I needed to keep writing and sending my poems out. The poem was a reaction to the killings of African- American men - particularly Trayvon Martin and Freddy Gray - and the protests in St. Louis and Baltimore.

Tell us something about the most difficult thing you encountered in this book’s journey. And/or the most wonderful?

The most difficult was trying to get it published. I sent it out to about 80 or more publishers and contests. It placed as runner-up in a couple of contests, but never won anything. I kept revising the poems and the order of them every time I sent it out. Finally, I decided to go back to the press that published my first book, Fleeing Back. They were very enthusiastic and supportive, so I decided FutureCycle Press should be its home. All those rejections helped inspire me to keep revising it - some even offered suggestions, which was helpful. In the end, I think the timing was right when I took it to FutureCycle - by then I had revised it as much as I could, I think, so it was more complete than when I started sending it out.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Maybe something like, "Check out this book of accessible, powerful, passionate poems!" I'm terrible at self-promotion.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

For me, to be a poet is a way of looking at the world. That's actually the scary part - I think poets see the world deeply, with a kind of clarity that makes us feel the pain around us, as well as our own. We see through BS to the heart of someone or something - or we try to. We can see deep meaning in small details, and try to make sense of the world through our art. Empathy is important - without empathy, a poet simply can't imagine poems. But empathy can be painful, and sometimes it's difficult to foster, especially for someone we know is a terrible person. What gives me the most pleasure in writing poems is the joy of working with language and creating something that's hopefully beautiful and moving. There's an ethical responsibility in being a poet because poetry can change the way people look at the world or themselves - that's part of the goal, anyway. That's both scary and one of the pleasures of writing.

I’ve heard poets say they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you? If not, what obsessions or concerns reoccur in your work?

I wouldn't say I'm writing the same story - in this book, there are a number of stories woven through it. But I do have obsessions that recur. The image of the wrack line is still appearing even in new poems. The ocean, the beach, nature - those are my obsessions. Lately, grief and death have become the reoccurring concern in my work. My brother (to whom the book is dedicated) went missing and is presumed dead in a scuba accident somewhere in the waters off of Bonaire, and I've been working my way through grief in my new poems. His death brought back a lot of the pain of my sister's death, over twenty years ago, and all that seems to be mixing in with grief about what is happening to our world now. My writing seems to be going in a different direction in my new work because of all that. In this book, though, loss, the ocean, family, and the world all work their way through the poems, too, though not as darkly as they seem to be in what I'm writing now.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

Yes, yes, and yes! Traditionally and historically, artists have always been at the vanguard of change. Art moves people to change in ways nothing else can inspire.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I think everything I read helps me; reading sharpens our ability to use language, but it also broadens our minds and inspires me, anyway, with ideas sometimes for topics or even with a sound or image, or even form.

What are you working on now?

Poems about grief and loss: my brother and sister's deaths, my parents' ascent into old age and ill health, all the terrible troubles following our election and the catastrophes climate change is beginning to unfurl on us.

Favorite places and times of day or night to work?

Early mornings and late evenings.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I'm in the middle of reading the poetry book, Afterland, by Mai Der Vang. These are amazing, powerful poems! Everyone should read this book. I just finished The Language of Moisture and Light by Le Hinton. These are also wonderful poems everyone should read.)I'm also currently reading the nonfiction book, Nomadland... but Jessica Bruder. This is an important book about an important social change happening across the country.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Basho, Yehuda Amichai, Adrienne Rich, Joy Harjo, Nikki Giovanni

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Q. Why is poetry important?

A. It teaches us empathy and helps us discover new ways of looking at the world or other people or cultures. It gives us beauty, passion, and even hope in a world that's rapidly losing all of those things. It feeds our hearts/souls - whatever you want to call the vital being inside of us. I don't think I'd want to live in a world without poetry. It would be an even crueler, more heartless world than it is now.

Purchase The Wrack Line.

About Patricia Hanahoe-Dosch:

About Patricia Hanahoe-Dosch:My educational background includes an MFA from the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona, and I’m currently a full Professor of English at Harrisburg Area Community College, Lancaster campus. My poems have been published in Rattle, The Paterson Literary Review, as well as Atticus Review, War, Art and Literature, Confrontation, The Red River Review, San Pedro River Review, Marco Polo Arts Magazine, Red Ochre Lit, Nervous Breakdown, Quantum Poetry Magazine, Abalone Moon, Apt, and Switched-on Gutenberg, among many others. My poem, “A 21st Century Hurricane: An Assay” was nominated for the 2014 Pushcart Prize in Poetry. Articles of mine have appeared in Travel Belles, On a Junket, and Wholistic Living News. My story,“Sighting Bia,” was selected as a finalist for A Room of Her Own Foundation's 2012 Orlando Prize for Flash Fiction. My story, “Serendip” was published in In Posse Review, a short story, "Hearts," was recently published in The Peacock Journal.

Visit her online at: pathanahoedosch.blogspot.com.

#element-4219dff8-dbbd-487c-9297-294bef85fbf6 .wgtc-widget-frame { width: 100%;}#element-4219dff8-dbbd-487c-9297-294bef85fbf6 .wgtc-widget-frame iframe { width: 100%; height: 100%; border-collapse: collapse; border: 0 none;}

Published on September 28, 2017 04:27

February 9, 2017

carpe noctem interview: kelly dumar

Two of Cups Press, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Two of Cups Press, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

“Tree of the Apple” is the name of my prose poem about planting a tree with my father as a teenager at a time of grief. The cover photo is of my parents on a vacation I refer to in “Sunday Afternoon in Memory Care He Remembers She’s Gone,” about my father looking at this photo after my mother’s death – and after he has Alzheimer’s, and remembers she’s gone.

Only three words? Alzheimer’s Father, Daughter. Can I have six? Story is an anchor – he drifts.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook?

I wanted to feel close to my father every day I was losing him to Alzheimer’s. Also, because he was smart and funny and brave and tender and hopeful and appreciative – and he fought back hard against losing what he loved, and I admired him for that even when it made caretaking scary and tough.

I wrote poetry as a way to understand what he was trying to tell us after he lost his words – his caretakers, friends, loved one. Also, his “wrong” words activated my poetic imagination with fresh, startling metaphors and point of view.

I wrote because what he was telling – his stories – fascinated me and being with him as an adult daughter I was often flooded with childhood memories. My siblings, my mother, I felt like I was writing to stay connected and whole as a family. I wrote poems to express love and also, perhaps, some rage at the devastation of the loss. I wrote to be clear about what our relationship gave me, how it shaped me. I admired very much how my father coped with dementia – how intensely he kept loving us, loving life, loving everyone he met. I wanted to inspire others to find a creative response to this kind of ambivalent loss – I wrote to keep my father vital in my life.

Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Myra Shapiro, a poet who kindly wrote a blurb for the cover, summed it up well: “We are in a world of lilacs and lovers, marrying earth to human nature, spanning life from courtship, to marriage, to Alzheimer’s and death.”

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

Finding, as a reader or writer - what I call the secret reveal – the “aha” – epiphany, insight, transformative awakening – why am I bothering to write this and revise and revise? Why is not a conscious awareness at the start – why doesn’t surface until many revisions, or even the final one. I write a poem to say what I didn’t know I knew or felt, and craft it mysteriously and beautifully - so that finding the secret reveal requires energy – and creates The secret reveal is the payoff, the take-away, for reader, writer, self.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

"Mrs. Beane’s Snow" is the heart of the book, because this poem embodies what I believe about our need for storytelling: the most meaningful stories we tell are ones the people we care about need and long to hear, over and over again. These are stories we learn by listening, deeply to what the people closest to us care about and believe, so we can tell them back to them in times of need.

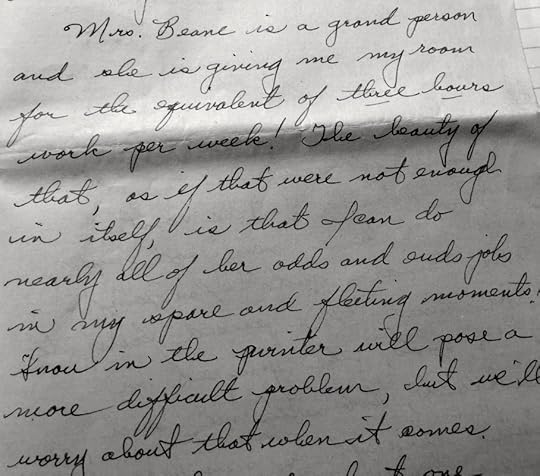

Mrs. Beane gave my father a home away home that he could just barely afford while he attended Harvard on the GI Bill. From the stories he always told us, it was clear the home she provided him with – in exchange for a few chores like keeping the coal furnace burning and shoveling her driveway when it snowed - made a profound impact. After Alzheimer’s, retelling the favorite stories he’d told us for years of his time with Mrs. Beane was a sure-fire way to comfort and distract him during difficult emergency room or doctor or dentist visits. Dad, remember the winter you broke your collar bone playing hockey, yes! when you lived with Mrs. Beane, and after they sent you home from the emergency room you shoveled her whole driveway with one arm in a cast?

Finding this original letter he wrote to his parents on Sept. 24, 1948 was a eureka moment – his first letter to his parents on his arrival to Harvard. This letter introduces this iconic figure in his life. And, such irony – his foreshadowing of the snow!

Mrs. Beane’s Snow

A story is an anchor. He drifts.

A story is a map. His direction

is lost. Mrs. Beane is a story. A name

is a compass. A street is a library. Her home

is a borrowed book. Story runs in circles.

Her driveway is a place to park. A river runs

past him. Brattle runs from Harvard Yard to Mrs. Beane.

Any ordeal is a landmark. A crisis has an ending

and before that a test. Once upon a time A pond

freezes in winter. Within walking distance

grows a boy with skates. This story has a sister.

A hero may be rescued more than once.

A story is a goal held by a net. Hockey is game

you win on ice. A threshold is college after a war.

A dormitory houses students with treasure.

A Brahmin can be a widow who lets rooms.

Young men of a certain character may call it home.

A battlefield is an ice rink. A collarbone broken

is a setback. A nurse can be a sister who is called.

Comfort is a cast but it’s not an elixir.

In snowy storms a driveway is a hurdle.

A stunning blow is one useful arm and a shovel.

A calling can be a lady in distress.

A shovel of snow must be lifted.

A shovel of snow must be heaved.

A shovel of snow must be lifted.

A shovel of snow must be moved.

One arm can lift one foot can heave.

There are so many shovels of strong.

A driveway is a place you can leave and return.

A river runs from mine to hers.

Home is a place to find what you give.

A listener longs for story.

An elixir is how it tells you.

Telling loves Mrs. Beane’s snow.

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you?

A poetry mentor recently told me I write about something rare in poetry: deep family love. I think that’s true. I write a lot about my parents, my childhood, my aging parents, my siblings, the way we’ve fought and made up, the ways we’ve protected, trusted, betrayed and leaned on each other; and also failed each other, and how our affection endures, how we’ve forgiven each other. I write a lot about breaks in relationships and how they are healed; also, about reinvention, the possibility of beginning again after loss.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

More than ever we’re called on to respond creatively – to resist, with our minds, emotions and actions authoritarian principles that threaten our democratic ideals. Yes, I find myself, writing more and more politically – even when I start out writing a nature poem, it seems to veer very quickly into political themes, consciously and unconsciously. I think this is happening right now to most of the poets I know – we cannot pay attention to what’s going on in the news without wanting to respond in writing as honestly, deeply, and creatively as we can to challenge small minds, authoritarian impulses, and careless thinking and action that bears grave consequences to people who deserve respect and protection.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Definitely dictionaries! And also Nature Guides. I write a lot from my daily photos of plants and other living and non-living matter I find in the woods – plus weather, clouds, sky, the Charles River, various swamps, and the seaside when I’m there. I look a lot of things up in various nature guides to get a name and identity of what I’m writing about. Sometimes I start writing about the photo with just one word that comes to mind spontaneously. Then I look it up, really chew on the meaning, go to the thesaurus, and pretty quickly a theme emerges, I have a way in to a first draft.

What are you working on now?

A full-length chapbook of poetry and short prose; also, a photo-inspired nature poetry blog I work on daily that I plan to develop into a book

What books are you reading that we should also be reading?

Difficult Women, Roxane Gay

Hillbilly Elegy, J. D. Vance

Pond, Claire-Louise Bennett

A Manual For Cleaning Women, Lucia Berlin

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Carolyn Forche

Sharon Olds

William Wordsworth

Seamus Heaney

Elizabeth Bishop

***

Purchase Tree of the Apple. [image error]

Kelly DuMar is a poet, playwright and workshop facilitator from the Boston area. Her poems are published in many literary magazines, including Tupelo Quarterly, r.k.v.r.y, Unbroken, Lumina Online, Kindred, The Good Men Project, Literary Orphans, and more. Her award-winning poetry chapbook, All These Cures, was published by Lit House Press, 2014. Her award-winning plays have been produced around the US and Canada, and are published by dramatic publishers. DuMar founded and produces the Our Voices Festival of Women Playwrights at Wellesley College, now in its 11th year. She serves on the board & faculty of The International Women’s Writing Guild. Visit her online at www.kellydumar.com or www.kellydumar.com/blog.

Published on February 09, 2017 04:41

February 3, 2017

Carpe noctem Book interview: Natalie Giarratano

Sundress Publications, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Sundress Publications, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The book went through several titles—including “Low-Water Mark,” a poem that is no longer in the book—and ultimately it seemed that “Big Thicket Blues,” the longest poem, captures many of the themes and moods of the book and works as the overall title. One of my mentors, Bill Olsen, suggested the title (I’m glad that I listened).

As for the cover image, I was introduced to the artwork of Karina Hean through poet Mark Turcotte and felt that Hean’s “Untitled 12” captured movement and landscape and decay all at once. There’s something dangerous in it—like it wants to slink off of the page and infect the reader. In a good way.

Three words: violence, music, skin

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

The world of the book is a microcosm of a small fraction of the shit that human beings do to each other. And I’m not only talking about large-scale violence, racism, and sexism but the micro-aggressions that are the norm for so many. I hope this book brings those things to (re)light and doesn’t allow the reader to look away. I hope these poems make the reader uncomfortable and question the ways in which they move through the world.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

For this book, I was writing irregularly, as is often how I roll for better or worse, and most of the poems were written over a four-year period. I don’t like writing eventual aborted poems, so I usually have a solid idea of what I want to write about before getting anything down (this has so many drawbacks). I also revise after reading poems aloud (in public or otherwise)—it’s amazing what the inner ear can miss.

The book also went through several major overhauls, the most recent being the addition of the bracketed fragments that show up throughout the book (these used to be parts of a crown of sonnets I’d written about Leadbelly but decided they needed to be fragmented to work more dynamically).

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I feel as though all of the Texas-y poems needed to be up front, in the reader’s face. The middle tackles more sexism and honors some of the women writers who’ve influenced me. The final section moves into the body but also out of America, still staring down racism and persecution on a larger scale. I later added the bracketed poems/fragments in places at which I felt they best complemented the poems around them. So, while at some point, the poems were strewn across the floor, there have been so many revisions since that I can’t even remember every major movement.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

New Coyote

It’s midnight in New Mexico, after who knows

how many noddings-off, CD changes,

and quiet tamale stands in Texas dust,

before we feel safe enough: hundreds of miles

from Johnson Space Center and the I-45

corridor, where Houston investigators

routinely interview the bones of schoolgirls,

plenty far from looming rock formations

when out of the tumbleweed along I-10,

howls find their way out—coyotes siren

for hours. They appear along the sides

of the interstate only to disappear into dry dark.

The Chevy moves on quickly, its instinct

to flee. It’s the coyote’s to chase us down,

it’s mine to turn the car around—save us all,

as if they need saving, these neophilic creatures.

But maybe it is in my nature to go back,

to be amazed at its smallness, how voice can be

much bigger than body—like those of us

eight-year-olds who sang “We are the World” for seven

dead astronauts. They fell apart, their shuttle dissolved:

a cube of ice in the fevered mouth of the universe.

And I used to be able to fall asleep

by tree song, that familiar lull of rustle

and fidget in wind. Instead: chickens rip

open wide the air with squawks as coyotes

raid the neighbor’s coop and schoolboys

pied-piper their prize-winning swine

to slaughter. How does this all work?

Coyotes showing up in subways and

elevators. That day. These newspaper

clippings. This looking back on it as though

terror had forgone the spark of city for sky,

and all the days since I’ve tucked inside

skin and sleep, partly existing, never awake

to becoming some small, wild dog that haunts

a desert it doesn’t need any more.

originally published in Southern California Review

So, I wrote this poem pretty early on, back in 2008/2009, and I chose it for y’all because I think it captures some of the searching, some of the violence, some of the grief, some of the not knowing how to change anything that is woven throughout the book. And after I’d written about half of the book, I noticed that I was writing a lot of animals into my poems. I particularly appreciate the adaptability of the coyote, and this poem was initiated, if I remember correctly, by researching articles about coyotes actually showing up on a subway car, etc. I long to be more coyote-esque.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

I might say, “Read this—what have you got to lose but time?”

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you?

I don’t know if “same story” applies, but I often write about Texas, which is where I’m from but haven’t lived for 12 years. Part of me is tired of going back to Texas in my poems. I don’t think fondly of many places in the state, so it’s pretty painful to keep returning. However, to say I will never return again is probably laughable.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

YES. We do not live or write in a vacuum. It seems more important than ever with this dangerous joke of a president/administration to be socially engaged. Words do matter. They often don’t seem as though they do, but sometimes they are everything, to the writer and hopefully to readers as needed.

The poems in Big Thicket Blues, on some level, address the normalization of racism and sexism and also how religion seems to too often play a role in that normalization.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Everything I encounter helps me write poetry: snippets of conversation, comments on a YouTube video, researched info (i.e. Leadbelly, James Byrd, Jr., Virginia Woolf), music of all kinds, a well-written TV show or film. Essays, poetry, everything in between. The spark for the title poem in Big Thicket Blues came about while co-editing Jake Adam York’s “An Unfinished Sentence” for Pilot Light, so even my other kinds of work can lead to poetry.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on getting back into the habit of writing after not writing much since I became pregnant with my daughter. Weird poems about ISIS news coverage or angry bits about my scary post-partum experience. Sort of in limbo with a “next project” and dealing with my feelings about being a newish oldish mother and, more recently, about the not-so-funny ineptitude of the leader of the free world.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

CD Wright’s Shallcross

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Yusef Komunyakaa

CD Wright

Allen Ginsberg

Lynda Hull

Rachel Eliza Griffiths

***

Purchase Big Thicket Blues.

Originally from small-town Southeast Texas, Natalie Giarratano received her Ph.D. in creative writing from Western Michigan University. She is the author of Big Thicket Blues (Sundress Publications, January 2017) and Leaving Clean, winner of the 2013 Liam Rector First Book Prize in Poetry (Briery Creek Press, 2013). Her poems have appeared in Sakura Review, Beltway Poetry, Tupelo Quarterly, Tinderbox, and TYPO, among others. She edits and lives near the foothills of Northern Colorado with her partner, their daughter, and pup. Find her online at www.nataliegiarratano.com. Learn more about her editing services at http://editor.nataliegiarratano.com/.

Published on February 03, 2017 09:18

December 22, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Lisa Rizzo

Saddle Road Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Saddle Road Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I had a surprisingly difficult time coming up with the title for my book. I’ve been working with this manuscript for about five years, coming up with one title after another before discarding them. Then when it was almost finished, I chose one of my poems, “Spelunking” as the title. However, when I tried it out on people, I had to explain what it was, repeating the word, often having to give a definition.

Then last November I went to a Tupelo Press writing conference. Introducing my work, I announced the title again. Jeffrey Levine asked everyone sitting at the table to raise their hands if they liked it. Almost no one did. When Jeffrey Levine questions my title, I pay attention. So I went back to the drawing board.

It took me about eight more tries before I finally found Always a Blue House, a line from the first poem in the book. As soon as I chose it, I realized that it had been waiting for me all along. I just wasn’t paying attention. I had to dig harder to articulate for myself what is the essence of my collection, what I am really trying to say with these poems.

Luckily choosing the cover image was much easier. I have been fortunate to work with what you might call a micro-press. That means that I was able to be involved in every step of the publication process. The press’s designer, Don Mitchell is a talented photographer. When I finally had a title, he sent me a huge file of possible photographs. The image of the stone on a porch rail struck me right away. Even though the blue house of my childhood didn’t even have a porch, this image conveys the emotional quality I was seeking.

Three words to sum up my book: grief, journey, growth

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Just as with my title, I struggled long and hard on the order of these poems. I searched the Internet for advice, and found the book, Ordering the Storm: How to Out Together a Book of Poems, edited by Susan Grimm. It contains essays by poets giving advice. I read the whole thing and marked several passages. I pondered over all the different permutations in which my book could be gathered.

Then I took all my poems and laid them out on the floor in three piles. After that, I read each poem again. It was only then that I truly noticed the weaker poems that needed to be weeded out.

I barely did any reordering after that. I didn’t go back to the advice I had read or try to follow any of their ideas. I just let the poems talk to each other. When I sent it to my publisher to edit, she made very few changes.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

Blue Angel

-- After the painting by Marc Chagall

Beside the open window,

she floats free, right hand over her heart.

Mouth open, an ecstatic sigh, she gazes.

Flowers burst open, deep indigo in their vase.

Her hair waves like a fish tail,

white wings like fins signal her advent.

A dress of water breaks from waves,

sparkles into the blue, blue world.

In a dream-swim under three crescent moons

a house is floating or sinking or settling

into sediment on the sea floor.

It is a blue house; it is always a blue house.

She is my angel and no one else's.

I can keep her my secret or let her free

into the world. I don’t care whether

she has flown in the window or out.

This poem, “Blue Angel,” is the preface to my book. I wrote it two years ago, but had been unsure of it, didn’t know if I should include it. Even so, a poet friend who read my manuscript suggested I start the book with it. As soon as I to put the poem at the beginning, I knew my friend was right. Somehow it needed to stand alone, waving its wings. It became the book’s heart.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Read this even though its poetry! Honest, I promise you will really be able to understand what I’m trying to say.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a poet means I am paying attention to every moment, vigilant for images to rise up in me. And then taking the time to sit down and write. This is what gives me the most pleasure, to tell my version of the world in words, to express what it means for a human being to live right now.

What scares me most about being a writer is that my words might not be good enough to express what I want to say. Also that horrible, cold fear that when one piece is done I won’t be able to think of something else to write! So far the well hasn’t dried up but as with many writers, that’s always in the back of my mind.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

I do think artists have a responsibility to respond to the world, but that can take many forms. I don’t write what I call political poems but I do think my poems address many of the issues facing women today. Our society still dismisses women’s lives as trivial and insignificant, and the larger publishing world follows suit. And because I am a woman living in a rabidly sexist society, I feel it is my responsibility to give voice to women’s lives. When I read your interview with Stephanie Rogers, I was glad she brought up the old feminist adage “the personal is political.” I think in our political climate today this still rings true. It is my political responsibility to give voice to what is personal to women.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a series about my fractured relationship with my father who now suffers from Alzheimer’s. I had never written much about him until he became ill, until his mental decline became severe. When I realized I would never have the opportunity to mend our relationship, I began to mourn him even though he’s still alive. It’s a strange feeling and one I’m still trying to articulate. There are several poems in Always a Blue House about him, but I’m not done grappling with this issue yet.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Pablo Neruda

Emily Dickinson

John Keats

Sharon Olds

Mary Oliver

***

Purchase Always a Blue House.

Lisa Rizzo is the author of Always a Blue House (Saddle Road Press, 2016) and the chapbook, In the Poem an Ocean (Big Table Publishing, 2011). Her work has also appeared in a variety of journals and anthologies. Two of her poems received first and second prizes in the 2011 Maggi H. Meyer Poetry Prize competition. She spent 23 years as a middle school English/Language Arts teacher. Now she works as an instructional coach, helping teachers improve their writing instruction. She blogs at Poet Teacher Seeks World and can be reached at www.lisarizzopoetry.com.

Published on December 22, 2016 13:28

December 20, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Camille-Yvette Welsch

dancing girl press & studio, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

dancing girl press & studio, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I've long admired Kristy Bowen’s book designs; it was one of the reasons I submitted to the press and I didn’t want to say some ridiculous idea and have it color her vision for the cover design. Instead, I asked if she had an idea and she came up with this, and I love it, the moonlight peeking through the wolf prints.

As for the title, I think that the idea of being full—full to bursting, stuffed—implies a certain discomfort, a border being suddenly met. In the course of the poems, the narrator longs for fullness of pantry, of well-being, of imagination, and as pregnancy takes over her body, that too becomes a fullness, and with each type of fullness, comes an insecurity. We have the stores, but how long will they last? My body is growing but is it too fast or slow? I have this house I ramble through, its protections and its people, but are they enough to keep me safe and whole? Are they too much? Will they keep me imprisoned?

Of course, on a literal level, the poems also speak to the full moons that have long marked the Native American calendar and revealed in their naming, what work is to be done, what nature has wrought.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

When I first became pregnant, one of my great fears about parenting was the never-ending need of a baby. As the third out of four kids, I know quite well that parenting is work. It is also joy and fun and lots of other things, but it is still three meals a day, bathing, dressing, changing, cleaning, and all of these daily and insistent chores.

The summer that I wrote this my two children had grown a bit more independent and I could take some time to write. A friend was struggling to write about the moon cycle and had given up. I picked up the idea because it so resonated with what I had come to understand more intimately about family life: There was no end; there were simply cycles of work. Sometimes daily, sometimes seasonal, often called phases, and as a family, we moved through them, trying to set things by to sustain us, whether it was story time or snuggling, or whatever. The hard work of living together and raising each other bore fruit that would be savored in times of scarcity, the luscious scent of clean baby, or the downy hair at the back of the neck, all the memories gleaming in their jars put up for when anger or frustration overwhelm us. In the book, I make sense of my conflating these two ideas.

The final thought that drove me is that with children, and with living off the land as people once did, each day thrums with some low-lying terror—a child should fall, be grabbed, get diagnosed, run away, have an allergic reaction, fall in love, fall out of love, be bullied, etc. Or, a crop should fail, there is blight, too much water, not enough water, mice eating through stores, a storm that takes down fruit trees, rabies, wild animals, livestock that takes ill, a rifle that doesn’t shoot, or shoots too well. The wolf that prowls outside the house becomes foe and id simultaneously for the speaker who has a hard time imagining a world outside the confines of the farmhouse while simultaneously recognizing that the freedoms of the wolf are also tightly dictated.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

My writing process involves one key element: get myself alone. I don’t have a home office where I can go and simply close the door. My desk sits in the library/family room where all the books are and many of the kids’ toys. I can write with noise, but not with the kids around. Whatever world I enter internally, they are always the barbarians at the gate, demanding entrance, and that is actually fine. When I am with them, I like to be with them.

So, my process is to get out of Dodge, go to a coffee shop, and start messing around for about thirty minutes—read Facebook, read some other poets, check out some online journals I like—and then write. I will write pretty steadily for about an hour, then it is time to go back home or grade or whatever. When I get an idea, I acknowledge it and then let it marinate until I can find that alone time.

Revision is always an interesting question for me. I do a lot of drafting in my head and as I write. I think I would have more evidence of that if I wrote longhand. Since I write on the computer, I simply consider, delete, and reconsider without record, thus I suspect that I do more of it than I recognize.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

The poems follow the Native American interpretation of the full-moon cycle. The name of each full moon correlates to a specific reality of life in that moment—from the spring blossoms to the running salmon.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I just want to be surprised—by language or image or idea. I read Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s The Paper Doll Fetus and the use of history and the strange perspectives were so startling and yet they felt so true and right that I just adored that book. I want that kind of immersion and awe in my reading.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This poem appears in the middle, but it gives a sense of some of the issues I was talking about earlier—the perceived freedom of the wolf, the never-ending responsibilities of household, etc.

Full Flower Moon

We are correspondents now,

like a game of telephone you cry

down from the mountain and I fill

in the silence with words. Here, I bend

over fields of strawberries, picking

and plucking, gathering enough

for pies and jam, to keep the taste

of summer in our mouths long after

the days have shortened. Red combats

darkness, a color war I knew little about

until winter came. I imagine your legs

stretching, eating the land. Sometimes

I dream of you and I, your scent

close in my face as we run, and each bite

I take is about this moment. I move across

fields, taking as I find it, thinking only

of this sharp taste, that tangy scent, never

of the gaping vortex of the cellars, the pantry,

the shelves ordered and waiting, a reminder

that everything must end.

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you?

As I don’t really write autobiographical stuff as much as I write persona poems, I don’t think that is quite as true. I am not working over the same knot of personal history. Of course, in every poem, unavoidably, I appear as thinker and perceiver on some level, and certainly, living as a woman in the United States, a lot of my concerns about feminism and how women are perceived and how we perceive ourselves, pervade my writing.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

I am not sure how you can avoid this. Writers are writing from a moment in time, and their mores are either in accordance or in conflict with that time. I think that tension makes its way to the page regardless. Some, of course, are more overt, but I think all stories have a kind of politics of perception to them. I am no different.

In my larger manuscript, which will hopefully find a home soon, I am looking at the Western beauty aesthetic through the eyes of the four ugliest children in Christendom. The story’s heart is the kids, not a political idea, but there is still a lot of commentary on beauty and ugliness, religion, adoption, academia, and so on.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Everything helps. Once you learn a shape, you can fill it. These are all shapes, and they keep you limber and ready for action. There is a great memoir by Randon Billings Noble where she uses the information that accompanies a prescription. I use that piece to teach my students, but also to remind myself to be open. Recipes become list poems, and anthropology books became the basis for the specimen reports in The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom, the manuscript I referenced earlier.

What are you working on now?

Assorted poems. I have been caught by the new room found in the Sarah Winchester house. I have no idea if anything will come of that. I did a 30/30 with ELJ Publications and used my mother’s 1952 Girl Scout Handbook as source material for all of the poems. That was a lot of fun. Now I have to figure out how to revise found poems.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Louise Gluck, Sharon Olds, Paula Meehan (though I would weep), Richard Hugo,

Lyn Emmanuel, Philip Levine. Okay, so that was six, but I love the list!

**

Purchase Full from dancing girl press & studio.

Camille-Yvette Welsch is the author of Full, a chapbook released with dancing girl press. She teaches at Penn State where she earned her MFA. She serves as book reviews editor for Literary Mama and her work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Menacing Hedge, Indiana Review, The Writer’s Chronicle, Atticus Review, Radar Poetry, Mid-American Review, Split Lip, and From the Fishouse, among other venues. Her manuscript, The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom, was a finalist for The Washington Prize, and her poem, "The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom Go to Cirque du Soleil," was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2016.

Camille-Yvette Welsch is the author of Full, a chapbook released with dancing girl press. She teaches at Penn State where she earned her MFA. She serves as book reviews editor for Literary Mama and her work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Menacing Hedge, Indiana Review, The Writer’s Chronicle, Atticus Review, Radar Poetry, Mid-American Review, Split Lip, and From the Fishouse, among other venues. Her manuscript, The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom, was a finalist for The Washington Prize, and her poem, "The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom Go to Cirque du Soleil," was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2016.

Published on December 20, 2016 13:13

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Camille-Yvette Welsch

dancing girl press & studio, 2016 ,THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

dancing girl press & studio, 2016 ,THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I've long admired Kristy Bowen’s book designs; it was one of the reasons I submitted to the press and I didn’t want to say some ridiculous idea and have it color her vision for the cover design. Instead, I asked if she had an idea and she came up with this, and I love it, the moonlight peeking through the wolf prints.

As for the title, I think that the idea of being full—full to bursting, stuffed—implies a certain discomfort, a border being suddenly met. In the course of the poems, the narrator longs for fullness of pantry, of well-being, of imagination, and as pregnancy takes over her body, that too becomes a fullness, and with each type of fullness, comes an insecurity. We have the stores, but how long will they last? My body is growing but is it too fast or slow? I have this house I ramble through, its protections and its people, but are they enough to keep me safe and whole? Are they too much? Will they keep me imprisoned?

Of course, on a literal level, the poems also speak to the full moons that have long marked the Native American calendar and revealed in their naming, what work is to be done, what nature has wrought.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

When I first became pregnant, one of my great fears about parenting was the never-ending need of a baby. As the third out of four kids, I know quite well that parenting is work. It is also joy and fun and lots of other things, but it is still three meals a day, bathing, dressing, changing, cleaning, and all of these daily and consistent chores.

The summer that I wrote this my two children had grown a bit more independent and I could take some time to write. A friend was struggling to write about the moon cycle and had given up. I picked up the idea because it so resonated with what I had come to understand more intimately about family life: There was no end; there were simply cycles of work. Sometimes daily, sometimes seasonal, often called phases, and as a family, we moved through them, trying to set things by to sustain us, whether it was story time or snuggling, or whatever. The hard work of living together and raising each other bore fruit that would be savored in times of scarcitye, the luscious scent of clean baby, or the downy hair at the back of the neck, all the memories gleaming in their jars put up for when anger or frustration overwhelm us. In the book, I make sense of my conflating these two ideas.

The final thought that drove me is that with children, and with living off the land as people once did, each day thrums with some low-lying terror—a child should fall, be grabbed, get diagnosed, run away, have an allergic reaction, fall in love, fall out of love, be bullied, etc. Or, a crop should fail, there is blight, too much water, not enough water, mice eating through stores, a storm that takes down fruit trees, rabies, wild animals, livestock that takes ill, a rifle that doesn’t shoot, or shoots too well. The wolf that prowls outside the house becomes foe and id simultaneously for the speaker who has a hard time imagining a world outside the confines of the farmhouse while simultaneously recognizing that the freedoms of the wolf are also tightly dictated.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

My writing process involves one key element: get myself alone. I don’t have a home office where I can go and simply close the door. My desk sits in the library/family room where all the books are and many of the kids’ toys. I can write with noise, but not with the kids around. Whatever world I enter internally, they are always the barbarians at the gate, demanding entrance, and that is actually fine. When I am with them, I like to be with them.

So, my process is to get out of Dodge, go to a coffee shop, and start messing around for about thirty minutes—read Facebook, read some other poets, check out some online journals I like—and then write. I will write pretty steadily for about an hour, then it is time to go back home or grade or whatever. When I get an idea, I acknowledge it and then let it marinate until I can find that alone time.

Revision is always an interesting question for me. I do a lot of drafting in my head and as I write. I think I would have more evidence of that if I wrote longhand. Since I write on the computer, I simply consider, delete, and reconsider without record, thus I suspect that I do more of it than I recognize.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

The poems follow the Native American interpretation of the full-moon cycle. The name of each full moon correlates to a specific reality of life in that moment—from the spring blossoms to the running salmon.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I just want to be surprised—by language or image or idea. I read Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s The Paper Doll Fetus and the use of history and the strange perspectives were so startling and yet they felt so true and right that I just adored that book. I want that kind of immersion and awe in my reading.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This poem appears in the middle, but it gives a sense of some of the issues I was talking about earlier—the perceived freedom of the wolf, the never-ending responsibilities of household, etc.

Full Flower Moon

We are correspondents now,

like a game of telephone you cry

down from the mountain and I fill

in the silence with words. Here, I bend

over fields of strawberries, picking

and plucking, gathering enough

for pies and jam, to keep the taste

of summer in our mouths long after

the days have shortened. Red combats

darkness, a color war I knew little about

until winter came. I imagine your legs

stretching, eating the land. Sometimes

I dream of you and I, your scent

close in my face as we run, and each bite

I take is about this moment. I move across

fields, taking as I find it, thinking only

of this sharp taste, that tangy scent, never

of the gaping vortex of the cellars, the pantry,

the shelves ordered and waiting, a reminder

that everything must end.

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you?

As I don’t really write autobiographical stuff as much as I write persona poems, I don’t think that is quite as true. I am not working over the same knot of personal history. Of course, in every poem, unavoidably, I appear as thinker and perceiver on some level, and certainly, living as a woman in the United States, a lot of my concerns about feminism and how women are perceived and how we perceive ourselves, pervade my writing.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

I am not sure how you can avoid this. Writers are writing from a moment in time, and their mores are either in accordance or in conflict with that time. I think that tension makes its way to the page regardless. Some, of course, are more overt, but I think all stories have a kind of politics of perception to them. I am no different.

In my larger manuscript, which will hopefully find a home soon, I am looking at the Western beauty aesthetic through the eyes of the four ugliest children in Christendom. The story’s heart is the kids, not a political idea, but there is still a lot of commentary on beauty and ugliness, religion, adoption, academia, and so on.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Everything helps. Once you learn a shape, you can fill it. These are all shapes, and they keep you limber and ready for action. There is a great memoir by Randon Billings Noble where she usesthe information that accompanies a prescription. I use that piece to teach my students, but also to remind myself to be open. Recipes become list poems, and anthropology books became the basis for the specimen reports in The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom, the manuscript I referenced earlier.

What are you working on now?

Assorted poems. I have been caught by the new room found in the Sarah Winchester house. I have no idea if anything will come of that. I did a 30/30 with ELJ Publications and used my mother’s 1952 Girl Scout Handbook as source material for all of the poems. That was a lot of fun. Now I have to figure out how to revise found poems.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Louise Gluck, Sharon Olds, Paula Meehan (though I would weep), Richard Hugo,

Lyn Emmanuel, Philip Levine. Okay, so that was six, but I love the list!

**

Purchase Full from dancing girl press & studio.

Camille-Yvette Welsch is the author of Full, a chapbook released with dancing girl press. She teaches at Penn State where she earned her MFA. She serves as book reviews editor for Literary Mama and her work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Menacing Hedge, Indiana Review, The Writer’s Chronicle, Atticus Review, Radar Poetry, Mid-American Review, Split Lip, and From the Fishouse, among other venues. Her manuscript, The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom, was a finalist for The Washington Prize, and her poem, "The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom Go to Cirque du Soleil," was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2016.

Camille-Yvette Welsch is the author of Full, a chapbook released with dancing girl press. She teaches at Penn State where she earned her MFA. She serves as book reviews editor for Literary Mama and her work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Menacing Hedge, Indiana Review, The Writer’s Chronicle, Atticus Review, Radar Poetry, Mid-American Review, Split Lip, and From the Fishouse, among other venues. Her manuscript, The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom, was a finalist for The Washington Prize, and her poem, "The Four Ugliest Children in Christendom Go to Cirque du Soleil," was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2016.

Published on December 20, 2016 13:13

October 31, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Emily Pérez

Center for Literary Publishing, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Center for Literary Publishing, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I wanted a title that drew attention to ambivalence about home, family, and domesticity. As this collection evolved, it had three different titles, and it wasn’t until I started writing poems rooted in the “Hansel and Gretel” story, where a house made of sweets is so prominent, that I settled on this title.

I like that both “sugar” and “stone” have diverging connotations. Sugar can be sweetness and promise, or something false and empty, and stone conveys both something steadfast and something cold and impassive.

The cover is the work of my brilliant friend, the artist Jenny Tran. I sent her a group of poems that felt representative of the arc and themes of the book, and then she and I worked together using a common Pinterest account to cultivate a collection of images that we thought resonated with the writing. I'm not a visual person, so I'm lucky Jenny is such a savvy designer. Based on our collection of images, she determined the right balance of darkness and light, nostalgia and modernity. She gave me a few different directions and then pushed further into the one that seemed most productive. I love what she created — its colors, textures, and tiny details, like the shadows cast by the paper house and girl on the green background.

My three word elevator pitch? Families are scary.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I wanted to tell the truth, as I perceived it: it is beautiful and terrifying to be a child, and it is beautiful and terrifying to be a parent. Families are a strange amalgam of choice and destiny. They can be both the safest and the most dangerous places to live.

The world I created is one where a fairy tale forest from my childhood imagination blends into the real world settings of my children’s first months on earth. It’s a place where known characters — Red Riding Hood, Gretel, the woodsman’s wife — speak the thoughts of a sleep deprived mother who is trying to determine whether her baby is her greatest love or her greatest enemy. It’s a world where the selfish and selfless collide through the figure of the artist-parent. The world is the past, the present, and the childhood imaginary, all swirled together into thoughts on what it is to be a member of a family and to depend on others.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Perhaps my greatest challenge with this collection was sequencing. I had a very rigid organizational scheme based on the worlds I saw each poem inhabiting: the world of parenting, the world of fairy tales, the world of love and loss, and the world of the past. I knew that the poems in different worlds spoke to each other, and I knew they would do a better job of speaking to each other if they could mingle, but I could not break them out of their sections. Even when I gave myself the task of reordering, at most I would move one or two pieces, and I’d call that a “radical” revision. I was stuck. Finally I enlisted the help of an editor, Susan Kan (of Perugia Press), and asked her to focus specifically on the sequence. She liberated the poems. Though I added some new pieces after the version she saw, the current order is ninety percent her vision, to the point that sometimes I cannot find a particular poem because it’s not where I would have placed it. While I wish I had been able to achieve the structural tension, release, and resonance that she achieved, I am glad that I finally got out of my own way and asked for help.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love to read and write pieces that are musical, where I learn something from the sound as well as from the meaning of the words. I always want to be surprised. To achieve that in my own work, I need to circle around a question I don’t know how to answer; similarly, I am looking for writers who take me down a path where the turns are unexpected.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

A New Mother Discovers Emptiness

That winter I resigned my role as hope—

with only two hands, smaller always than I’d needed,

and twice as many yearning mouths to fill.

I concocted stories, songs, and spells,

and once we’d sucked the marrow clean

from words, I spun, I wove, I kept conniving to confect,

but there’s only so much sweetness in the world.

I poured pity on the two of them,

just children still, all their pleasure flown.

In each other’s faces we reflected want,

so I sought solace on my own.

I found it first within the darkness of the woods,

which rendered me invisible. I found it next

within the distance of the stars, whispering how miniscule,

how meaningless my sorrows. Who insists on being heard

when faced with all that space? What is emptiness

when perched upon the lip of a black hole?

I tried to teach those little ones to see,

I pushed them toward the door.

And when they would not go, I locked them out myself.

Here is a pathway, here is bread, I said, you’ll learn

these walls were never real. Make a new home

inside your head. To those who ask me:

What if they are calling in the woods?

I say, at least they’ve learned to sing

and to those who wonder what if

they’re trembling with fear?

I say, then at last they’re full.

Though I didn’t realize it at the time I wrote it, this was the poem in which several themes I’d been exploring coalesced. It helped me understand which poems belonged in my collection and which ones did not.

Though the persona speaking is the woodsman’s wife from “Hansel and Gretel,” she is also the modern mother who is struggling to find the line between her own wants and needs and her children’s. And though this piece primarily empathizes with the mother, I think it also asks the reader to empathize with the cast-aside children.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Right now, more than other kinds of writing, it’s speech that I find inspiring. I write down stories that my children tell or the way they turn a phrase (for example, my younger son starts many phrases with the word “ever” instead of the word “if” — such as “ever I see a horse…”). Their language helps me see and hear the world in a new way.

What are you working on now?

My sons are becoming increasingly interested in weapons, especially guns. Meanwhile, I'm a high school teacher in a state known for its gun culture; several mass shootings have occurred near where I live and work. My school and my children’s schools practice lock downs. We prepare ourselves for armed intruders. I’m writing now about my children growing up in this culture where they must practice for encounters with violence, as well as the ways I am grappling with their desire to “play” at violence.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

You ask Me to Talk About the Interior, by Carolina Ebeid

***

Purchase House of Sugar, House of Stone.

Emily Pérez is the author of House of Sugar, House of Stone (2016), and the chapbook Backyard Migration Route (2011). She holds degrees from Stanford University and the University of Houston, where she was poetry editor for Gulf Coast and taught with Writers in the Schools. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in journals including Poetry, Diode, Bennington Review, Crab Orchard Review, Calyx, Borderlands, and DIAGRAM. She is a high school English teacher and dean in Denver, where she lives with her husband and sons. Visit her online at www.emilyperez.org.

Emily Pérez is the author of House of Sugar, House of Stone (2016), and the chapbook Backyard Migration Route (2011). She holds degrees from Stanford University and the University of Houston, where she was poetry editor for Gulf Coast and taught with Writers in the Schools. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in journals including Poetry, Diode, Bennington Review, Crab Orchard Review, Calyx, Borderlands, and DIAGRAM. She is a high school English teacher and dean in Denver, where she lives with her husband and sons. Visit her online at www.emilyperez.org.

Published on October 31, 2016 07:45

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Catherine Strisik

3: A Taos Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

3: A Taos Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each?

The title came as a result of the poems, through realization that the disease, Parkinson’s, was taking away/stealing my husband/marriage from me, just as a mistress does. The cover image was chosen for its haunting beauty, its transparency, its fragility. The sculptor Karen Lamonte sculpts life-size figures from glass, which for this book was the perfect image for a subject that was/is so jagged, rough, chipped, delicate.

If I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Seduction, passion, grief

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Ultimately, The Mistress is a love poem written through the textured experience of a long and passionate marriage. Then enters the mistress: Parkinson’s disease. The book is framed in one of the most imaginative ways: persona or mask where various voices speak throughout the book. Throughout the narrative, the mistress has her say. Breaking The Mistress’ grasp are a series of love poems each dated before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s. The book is structured this way, as an invitation to the reader to exhale, and trust the passion, the body, the spirit as it is presented.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Because of the fragility and heartbreak of the subject, my husband’s Parkinson’s disease, in order for me to find my way into the poems, I discovered that writing from persona at least initially was successful. The disease speaks as The Mistress, Kilimanjaro sighs, medications chant. I was alone in a monastery when I began this book, needing complete silence and privacy except for the sound of bells.

My revision strategy: I read each poem aloud hundreds of times listening for its musicality, its needs, which are often very different than what my needs are as the writer.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

The ordering of the poems in The Mistress was deliberate. The voice of The Mistress acts as say, the frame for the poems contained within. Woven throughout are voices of others, the neurologist, the wife, he says, she says, Kilimanjaro, an insecticide, and always is the wife’s voice that speaks the poems “Before We Were Three/” that impress upon The Mistress, and the reader, that there was this, this life, this love, this passion, this wholeness of marriage before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s, The Mistress.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love to experience this: “What!!!!! Are you kidding me?” Or this: “How did she/he move me from here to there?” Or this: “I can't breathe because of where this poem took me.” Or this: “ I am at great peace because of this poem.” Or this: “I'm crying because of the simple brilliance of this poem.”

I love to see that a poet has experimented with white space, therefore breath. I love to study how a poet, with clear and simple language, and with few words, has written a poem that affects me so deeply, into my marrow that I can't do anything but read and reread, and tape it to my refrigerator for others to see.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

Little known but one of the earliest symptoms of Parkinson’s is the loss of the sense of smell that can occur in many people up to 15 years before a diagnosis of the disease. For me, for us, in our marriage, this was a terrible realization that my husband could no longer smell me. The grief was astonishing in fact because the sense of smell is powerful, an aphrodisiac, and knowing that there was now this loss when already there were so many, caused yet another grief. The loss is addressed in various poems in the book; this one is set on our property. I wouldn’t say it galvanized the writing for the rest of the book, rather, it was another sign of the deterioration of brain cells in my husband’s brilliant brain therefore another beating by The Mistress to our once fiery marriage.

Your Loss Comes On Like Grief/

My Grief Comes On Like Longing

Even the mud smells

good I say and you say

yes

yes along the San Cristobal Creek

where we drop to our knees--

sanctuary in brilliance of soft afternoon glow

where I breathe the scent of mud where

you breathe—my set of wet

eyes that perhaps

your eyes see neither of us paying

attention to the song, loud in my heart, and yours

the mud smells good the mud smells good

glee swelling my flesh.

Please.

Breathe me in—unexpected

desire for you upon

my lips, an hour’s reflection

of creek flow during early spring,

open somehow quiet in

its appetite.

I am a scentless woman

to you, and to her, too.

That the mud smells good smells good that I want you

to say I remember.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

I might say, "Hey! I’ve written this book of poetry and I want you to have it to read and share with others, and if you want to contact me later to talk about it, please do!"

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

At this age and at this point of my life as a poet, I cannot imagine my life any other way. I live for my own creativity as a poet, and for others’ poetry, also. There is nothing that scares me about being a writer. I am at peace when writing. I love the process: from the earliest impetus that most likely came about in a stream of consciousness writing, to discovering the poem, the language, to line breaks, the craft, the sound, the voice, to the presentation to other poets for critique, the presentation of the poem out into the world. Each gesture of writing a poem, even in the most emotionally difficult poems, is spiritual, helping me grow as a poet.

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you?

No.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

There are some novelists whose writing is so poetic that I refer to their books for the rich vocabulary and their use of language, such as Colum McCann. And, always a thesaurus.

What are you working on now?

I have in process three separate manuscripts now, but Pitchfork is the working title of the one I’ve been most absorbed in over the past year. It consists of small poems about insects and the insect world. I research endlessly when writing each book so now have sites, articles, and picture cards about insects on the planet. And the poems, though many of them humorous, are really once again complicated with the intricacy of human relationship.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

There are two: A Life Well Worn by Larry Schreiber and Canto General, Song of the Americas by Pablo Neruda, translated by Mariela Griffor; Jeffrey Levine, translation editor.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Odysseus Elytis, Pablo Neruda, Patricia Smith, Galway Kinnell, Orlando White

***

Purchase The Mistress.

Catherine Strisik is a poet, and author of The Mistress (3: A Taos Press, 2016) and Thousand-Cricket Song (2010; 2nd edition, 2016 Plain View Press), and manuscript-in-progress, Pitchfork. Active in the Taos poetry community for over 33 years, Strisik’s poems appear in Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Drunken Boat, Connotation Press: An Online Artifact, Kaleidoscope, Tusculum Review, and elsewhere, and have been translated into Persian. Strisik has received grants, honors and prizes from CutThroat, Peregrine, and Comstock Review, The Southwest Literary Center, The Puffin Foundation, as well as residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, Truchas Peaks Place, and Christ in the Desert Monastery. Strisik is co-editor of Taos Journal of International Poetry & Art (www.taosjournalofpoetry.com), and also teaches privately and is available for readings, workshops, and interviews. She lives in San Cristobal, New Mexico. Visit her online at www.cathystrisik.com or www.taosjournalofpoetry.com.