Nicole Rollender's Blog, page 5

April 19, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Lois Grunwald

Finishing Line Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Finishing Line Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The book’s title was my first choice and it has remained the same for several years while I was working on a full book of poems and the chapbook. I loved the word “Capacious” and felt it encompassed the spaciousness and largess that I wanted to convey about this world and the possibilities inherent in our lives and the lives of creatures that share our world.

I looked through four or five photos and an image of a painting of the minarets, a mountain sub-range in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the setting for the poem, “Capacious Earth.” Then I remembered a 1936 photo I’ve always liked of Sierra mountaineer Norman Clyde descending Alta Peak in the Sierra. I thought it would be perfect for the cover because it shows the daring and strength of the “famous” climber (Norman Clyde) that I refer to in the poem, “Capacious Earth” (though his face is in shadow and so he’s also an anonymous climber, which I liked) and that he’s in a very capacious place. Being out on a limb, on a tightrope of sorts, taking risks, and exalting in the beauty and wonders both in the natural world and in a relationship are threads that I feel run through the book’s poems.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it?

I wanted to convey, I think, something that I didn’t have words for. I felt that the best way to do that would be to detail the experiences themselves and let those moments speak for themselves. Often we feel two or more things at once and I hope that the poems convey this fractured and very human nature of existence. My thought was about creating poems that would reflect the unexpected and mysterious nature of the heart, how loving someone unconditionally can be the most upending and life-changing experience one can have. For me, that love was linked to the natural world and all the beings that reside in it and share our world with us. I believe real life or actual connection occurs in small moments between people, sometimes with words but more often not, as words can be poor conveyors. What is telling, I think, is the actions of the two people when they are together, what they actually do to help one another, console, be open, truthful, trusting, and have concern above all for another’s well-being.

I chose the other poems in the collection to hopefully speak to this central relationship by envisioning how the content of those poems intersected that relationship somehow, whether that be in the historical lives of others, people and animals going about their lives, or an experience in a wilderness landscape. To me our lives and the lives of everything around us is intertwined. One poem speaking to another is a tricky thing and it’s up to readers to decide what kind of connections they see, where the poem takes them. It’s an intuitive process and sometimes a poet may not see the connections until later or see different interactions that may not have been intended. But I feel that what we experience in the natural world can reflect or inform our inner and outer life, sometimes in surprising ways. It’s a compassionate exchange.

Others may see other things in the poems in the collection. I’m always interested in what others see in my poems. Once you send a poem out into the world it belongs to everyone to make of what they wish.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

It’s an entirely intuitive process that I used in combining older poems with newer ones for Capacious Earth. I didn’t know what the book would look like until after I saw the poems side by side, added new poems, took out others, and reassembled them several times. Then I began to see perhaps a pattern of sorts. I found some of the older poems spoke to the newer ones. In going over the manuscript, I took out older poems that I felt were weak or didn’t serve the book, even though I was attached to some of them. I had to be ruthless in cutting those out.

My writing practice for Capacious Earth was to go camping or hiking in the wilderness or taking a walk by a creek or meadow near where I lived, bring my notepad or laptop with me, and write whatever happened to come up. In writing these poems, some of which were very emotional for me, it helped to be outside. When I’m outside, I often have a thought about a sentence or a word which will then start a poem. Or I’ll have a vivid memory of an interaction that I feel needs its story told. I usually come at poems in an oblique way. I love to observe what’s going on around me, the small details. I also read a lot of historical and science-related nonfiction, and something will grab me and need to be explored.

In a first draft, I just write out everything that comes to mind without editing or judgment. Then I go back, and delete, or rearrange, or recreate, based on whether something sounds right or not, a better word could be used, or the syntax isn’t conveying something that it might need to. I often think of what other poets have done and look them up for inspiration and to jolt myself into writing perhaps in a sharper or different way. Once I feel a poem is complete, I’m done with it, and move on to another one. I was a reporter at one time, so I’m accustomed to rewriting and editing, which is helpful, because I’m not that attached to words or lines.

I have a poet friend who reviews my poems and tells me what works for her in the poem and what doesn’t and suggests changes I might consider. Or she has questions about a line or stanza that lead me to think about where the poem is going. That’s enormously helpful.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

The opening poem, “Only This” was always my first poem in this collection. I also knew what the final poem would be. After that, I laid the rest of the pages on the floor and decided how they sounded next to one another.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I like poems that hold back a bit from an emotional standpoint. I think a poem is more interesting and powerful when something that’s very emotional or poignant is understated, or contrasted with something that seems entirely unrelated (but is, in some way). It’s important I think to have emotional honesty in poems, to tell the truth, and not be afraid of your truths. That’s all any poet or writer has is the truth of what the person or personas inside them have to say. I also like to change the subject in a poem and take it to another visual or mental perspective, much like our own contrary minds work. One moment you’re watching a bird’s path along a rail, then you notice there’s snow on distant peaks, then someone unexpected knocks on your door, who seems familiar though you never met them, and so on. I love poems that hit a true emotional cord or take me into the life (or lives) of another or that suddenly veer to a natural-world place or image. I find that captivating.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The poem is, “Lake Sunrise” which is a little short of the middle of the collection. I chose this poem because it shows a moment which was quiet and I felt heartfelt for the two people who are central in the book. It also shows, at least for me, the tenderness and desire that was uninhibited in those moments. It also shows in my view the connection, the unspoken need. There were other instances like that and other poems that I wrote about those moments, but this was the one that made it into the book. It sort of encapsulates the bond. The poem, “Blessing,” which is one of the first poems in the book, was a later event that spoke to me very deeply because it was a purely spontaneous, visceral touch that went on and on and which I didn’t want to end. “Lake Sunrise” had just a tinge of poignancy, but “Blessing” shows, I feel, how both joy and sadness can sit side by side. So, here is “Lake Sunrise.”

My intertwined hands reach out to you

in your grandfather’s red plaid shirt. A need

to touch again. There by my office

door. There’s a yellow glow in that warm cave

and nearly all the occupants have left

the building as if they will awake

under some new star

and never return. I say, you look good. Our eyes

hold each other, linger. The colts

are loose now. A colleague interrupts us

and then capitulates.

You bend your head and wish him away. Alone now,

your cheek near mine when I offer a map

of the far-off state in which you’ll travel

tonight after a Nevada car camp and waves

of Utah cliffs. Our arms then hands touch

near the 40th parallel which I’ll see

as photos later in your office with October darkness

in the window.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

What scares me the most is when I stop writing for a time. I’m anxious that I’ll never start writing again. I feel a need to get back to it. I assume that my first draft of a poem may or may not work and at any rate, it’s just the beginning and I’ll need to revise. I assume some poems will be bad at first, or the words will fail me, or it’s just not going in a direction that works. I’m not afraid of failure because if you work at something, you’ll sometimes fail. I expect my poems or a book to be passed over many times, and they have been. I try not take it to heart because it’s not productive. I just keep working at it, trying to make the poem better or a book better. I think that’s the important thing.

I love the solitary act of creating a poem. I was an artist, drawing and painting in my 20s, and it’s the groove that you get into when creating that’s wonderful to me. I love to hash out a poem, then go back and edit and change things, sometimes dramatically, to get where I want a poem to be. I love the physical act of typing or writing a poem and the thrill of not knowing where the poem is going, what images or lines will arise, until its finished, and even then, not knowing exactly what you have, as if there is another force that’s beyond you at work, which I feel there is. I feel a poem isn’t really finished but that the poem ends without an ending. A good poem shouldn’t really end but leave a reader thinking about possibilities or a thread that makes them think of connections that the author may not have intended or thought of.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

Really, almost anything works for me. I love reading other poets. I like Barry Lopez’ book, Home Ground, Language for the American Landscape. I like nonfiction about pre-industrialized America. I’m fascinated with what early explorers saw—a virtual virgin wilderness populated by American Indians. At one time I read a lot of nature writing, like Loren Eiseley (The Immense Journey), Mary Austin (Land of Little Rain), Annie Dillard (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek), Gretel Ehrlich (The Solace of Open Spaces), and Terry Tempest Williams (Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place) to name a few. These authors have stayed with me.

What are you working on now?

A new collection of poems.

What books are you reading that we should also be reading?

Madness, Rack, and Honey by poet Mary Ruefle, Pacific Walkers by poet Nance Van Winckel, Sand Theory by poet William Olsen, Proofs and Theories, Essays on Poetry by Louise Gluck, Walking to Martha’s Vineyard by poet Franz Wright, and Interrogation Palace by poet David Wojahn.

***

Purchase Capacious Earth from Finishing Line Press.

Daniel Colegrove Photography Lois Grunwald’s poems have appeared in the Iowa Poetry Source anthology Leaves By Night, Flowers by Day. An author of many science and natural-history related articles for her work for environmental agencies, she also has led Sierra Club groups on wilderness conservation projects. She received a B.A. degree in journalism from California State University, Fresno, and holds an MFA in Poetry from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Capacious Earth was a finalist in several poetry publications before being selected by Finishing Line Press. It is her first book of poems. Lois grew up in California’s Central Valley and has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, Ventura Country, and Southern Oregon. She now resides in eastern Arizona. Visit her online at

Daniel Colegrove Photography Lois Grunwald’s poems have appeared in the Iowa Poetry Source anthology Leaves By Night, Flowers by Day. An author of many science and natural-history related articles for her work for environmental agencies, she also has led Sierra Club groups on wilderness conservation projects. She received a B.A. degree in journalism from California State University, Fresno, and holds an MFA in Poetry from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Capacious Earth was a finalist in several poetry publications before being selected by Finishing Line Press. It is her first book of poems. Lois grew up in California’s Central Valley and has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, Ventura Country, and Southern Oregon. She now resides in eastern Arizona. Visit her online at www.loisgrunwald.wordpress.com.

Published on April 19, 2016 11:56

April 12, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Christina Veladota

Aldrich Press (an imprint of Kelsay Books), 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Aldrich Press (an imprint of Kelsay Books), 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The title Clutch & Brood comes from my obsessing over some house finches that took up residence on my carport the summer I wrote most of this chapbook. I began thinking about these two words in relation to birds and also in relation to family. The multiple meanings of clutch and brood seemed to open up the central themes and images in the book.

Photography is a hobby of mine, so I shot the cover for this book, as I did for my first chapbook, The Girl & Her Lions (Finishing Line Press, 2010). My daughter, Sophie, is the girl in the image. Since the concept of family is important for this book, I thought it appropriate that Sophie appear as the bird that holds the empty nest for the reader to consider.

The three words that come to mind to describe this book are haunting, intimate, and… well… brooding.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

My mother died of Alzheimer’s a few years ago. If you’ve been through this with a loved one, then you know how it feels to “lose” the person before she is actually gone. The truth is that as we lost her, she also lost us. She was living in a time before my sisters and I existed. She was a child, still living in her father’s house. She was, in a way, haunting her own past.

Clutch & Brood, a collection of prose poems, explores how memory, even for those of us without any type of dementia, can be a kind of haunting. The poems are inspired by lived experience, but I wouldn’t say they are autobiographical, per se. They focus on the concepts of family and of memory and memory loss.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

My process involves a lot of reading and napping, which makes me sound incredibly lazy, I know, but catnaps do often help me find the poem I’m trying to write. While working on this particular collection, I wrote notes and early drafts while sitting outside and took breaks to work in my garden. I was fully committed to the process but also unwilling to force anything onto the page.

I intentionally repeated images, words, and phrases among the poems, so they would seem in conversation with one another. My hope was that the reader would experience this in much the same way we experience memory, when something familiar is re-imagined in a new context.

The drafting stage is always full of inspiration and creative adrenaline, and I love that feeling of losing time because I’m so immersed in what I’m writing. Revision requires me to come back to reality and see with new eyes what I’ve put on the page. I approach revision as I would a puzzle. What words, images, or “pieces” are necessary (or unnecessary) to help complete this poem? Though I enjoy revision, it can also be the most frustrating aspect of writing, particularly when I realize (as I often do) that the poem isn’t going to work in its current form.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I actually did lay the pages on the floor at one point. I also taped them to the side of my bookcase for a spell. My method of organization wasn’t haphazard, but it wasn’t an exact science, either. I wasn’t looking for a narrative arc, more an arc of ideas, so the images would unfold in a meaningful way for the reader.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love reading a collection and finding a poem so amazing I have to close the book and set it aside for a few hours; a poem that compels me to close my eyes and sit in silence, so for a few moments, I can continue to live inside its world.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

When I was a child, my family spent time every summer in a tiny cabin on Three Mile Harbor in East Hampton, NY. I’ve often mused over the idea that we’re still there, haunting the place, and if I were to return, I’d see or sense the ghost of my child-self running through woods and down to the beach. The following is the penultimate poem in the book, and it addresses the concept of memory as a type of haunting. This recently appeared in The Laurel Review’s special issue dedicated to the prose poem.

If I were to Haunt You, I’d keep it to Myself

We already know we’re ghosts, but who among us will admit it? Our father sweeps the sea of its oysters while we play jellyfish roulette, diaphanous bullets in their chamber. The horseshoe crabs are armored knights retreating from the joust; we place our bets against them, go with the mussels, their open mouths so many razors threatening our skin. Evenings our mother gives us flashlights, but we call them fire & char the night with our names. The moon is the least of our worries; it is already a perfect cigarette burn among ashes. We say no to the stone that calls itself planchette, but can’t ignore its séance. Cicadas radio their tympani to the owls, glooming the trees. You are the last red song in the haunt of my eyes. Our candles gutter little birds that startle the sky.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Um… Here’s five bucks?

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

Writing poetry is challenging – I wouldn’t want to do it if it were easy – but I end up having a love/hate relationship with it sometimes, particularly when I struggle with a project or find myself adding to my collection of rejections. I knew at the age of nine that I would be a writer, and I have never waivered from this path. Writing, for me, isn’t a choice; it’s just who I am. So even when I “hate” writing, I don’t know what I’d do without it.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

When it comes to inspiration, I take it where I can get it. One of the poems in my first chapbook was inspired by the prophecies of Nostradomus. I’ve even been inspired by stories from the news and odd syntax found in weather reports. I read just about anything I can get my hands on.

One of the books I’m reading now is Susan Sontag’s On Photography; I’m intrigued by her discussion of Diane Arbus and her choice of and approach to her subjects. Sontag also quotes Nietzsche as having said, “To experience a thing as beautiful means: to experience it necessarily wrong.” I love that.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a full-length collection that continues to explore memory and the family.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir. You should read it, too.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Emily Dickinson, Mary Ruefle, Anne Sexton… and I’m going to cheat a little here and say Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Flannery O’Connor, because their prose is so beautifully poetic.

***

Purchase Clutch & Brood here.

Christina Veladota’s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in a number of literary journals, including The Laurel Review, Hotel Amerika, The Journal, Bellingham Review, and Mid-American Review. The author of the chapbook The Girl & Her Lions (Finishing Line Press, 2010), she currently serves as an associate professor of English Composition & Literature at Washington State Community College in Marietta, OH. She is a recipient of a 2014 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council. Visit her online at: www.christinaveladotapoetry.com.

Christina Veladota’s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in a number of literary journals, including The Laurel Review, Hotel Amerika, The Journal, Bellingham Review, and Mid-American Review. The author of the chapbook The Girl & Her Lions (Finishing Line Press, 2010), she currently serves as an associate professor of English Composition & Literature at Washington State Community College in Marietta, OH. She is a recipient of a 2014 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council. Visit her online at: www.christinaveladotapoetry.com.

Published on April 12, 2016 06:07

April 5, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Louisa Adjoa Parker

Cinnamon Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Cinnamon Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The title is the last line in the book, and I felt it summed up the collection: something that had been kept in the dark for many years, emerging into the light. The cover is a standard cover that my publisher uses for pamphlets, but I like the simplicity of it and think it suits the poems very well. Three words that come to mind to sum up the book: Trauma, letting, go.

What were you trying to achieve with your book/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I’d had this awful year, and carried it around with me for twenty years but not really got it out and properly looked at it. So that’s what the poems enabled me to do – look at it and say, that was awful, it was really tough, but I got through it in the only way I could at the time, by carrying on going, looking after my babies and not falling to pieces because they needed me. I was trying to show the reader this world of mine from twenty years ago in a rural part of Nineties Britain – how isolated this young single mother felt, how scared, how these terrible things just kept on happening to her and her family. It’s very much about me, the two children I had (or was about to have), my sister, the men who died, (and my Mum’s in it a bit). There are also the people who seemed to be against us, who blamed my sister for her boyfriend’s suicide, even though she was only a nineteen year-old girl and he was a grown man. And my racist neighbours, who wanted to drive us out. I remember being in the flat we’d moved into, on the first floor, and looking out of the window and feeling as though we were trapped in this tower, looking down on the world outside.

Blinking in the Light tells the story of the hardest year in the narrator's life -- her boyfriend died during her second pregnancy (from “The phone call,” “My daughter's dad has died./ It was vodka and a bag of smack.) and her sister's boyfriend died from hanging himself (from “The week she turned 19,” “...he dangled upstairs/ with broken neck and broken dreams”). We learn in the last poem that these events had occurred 20 years prior, and yet in the preceding poems, the event details are so precise, and feel as if they had just happened recently; the grief and other associated feelings are so cuttingly on point. What is it that you want readers to learn about the grieving process from the time reveal in the last poem?

(It was actually my ex-boyfriend who died as we weren’t together at the time, although he was my first love and I was still very emotionally connected to him.) The time reveal in the last poem wasn’t meant to have a significant impact on the reader, it was more that the poems were written chronologically so that was just how it ended up. I wrote nearly all of them after a therapy session during which I realised that I hadn’t processed what had happened properly yet, so writing them was part of that process. I suppose readers can take from this something that we all know, and is a cliché: that time can heal, and also that sometimes it isn’t safe to look at trauma, but maybe there will come a time later on when it is safe.

This chapbook covers some hard-hitting social issues: suicide (could it have been prevented, and the guilt it leaves with the living) and drug overdose that causes death. Also, in just one poem, “Our new neighbours,” the narrator says, “They don't like 'blacks.'/ They bang on their ceiling with a broom/ every time my daughter runs/ across the room.” Despite the chapbook events occurring two decades ago, these issues are still relevant today. Do you see the poems as being a social commentary? Did you want the poems to feel polarizing to readers, as if they should take some type of action after reading them?

I think it’s incredibly sad that the issues in the pamphlet are still relevant across the globe today, if anything, they could be seen as being worse. The poems are a social commentary, yes, as I feel a lot of my work is. I want to write about the experiences of marginalised individuals, people who feel as though they are on the outside, looking in. I have belonged to a number of marginalised groups, and I hope to encourage readers to think more about equality and social justice generally, and by hearing stories such as this one, to be less judgemental. We all have a story to tell – we all have made bad choices which have ended up with difficult consequences. I was a young single mother on benefits (welfare) during the period in which the poems were set, but there were a number of factors which led me to be in that position – experiencing domestic violence and abuse as a child and adolescent; gravitating towards other damaged young people because we had something in common; living in a time when women had the freedom to have their babies without being forced to give them up, and so on. I hope readers can have empathy with others who find themselves in difficult positions like this one, and not judge them harshly.

In the poem, “Fireball,” the narrator's new baby is growing and thriving, and lest readers be lulled into thinking that the recent deaths and hardships are receding into memory, the narrator closes the poem with these lines: “I have to make sure death/ isn't just around the corner/ I have to make sure it won't come/ and crash into our lives again.” Many of the poems have poignant moments like this, ones that individuals in similar circumstances can understand. Did you see this chapbook also as a tool to help others who've lost loved ones to suicide and drug overdoses? Have you had responses from readers to this effect?

I hope that the poems could be used as a tool to help others in similar situations, in two ways: one by showing that there is hope, that we can overcome challenging and traumatic events and reach some kind of peace with them, and two, that traumatic experiences can be transformed into Art – whether that be writing, the visual Arts, performance or any other genre. We have the ability to take suffering and turn into something others can appreciate, relate to, find beauty in or taking meaning from. I haven’t had many responses from readers so far (as the official publication date is February 2016) but I look forward to hearing from anyone who the poems have helped.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I had already written ‘Blue-eyed Boy’ and ‘The year she turned nineteen’. After a therapy session I decided I had to write about the year, and came home and got my old diaries out. They had a few entries from that year, and I jotted down details, like the onions on a kitchen floor, or the sound of seagulls, a green rucksack, then I wrote for hours. I then spent the next couple of days revising the poems, sent them to my best friend to look at, and left them for a while. It’s always good to have a little break and go back to something with a fresh eye. I revised them a little more, then sent them off to a few competitions.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

These poems are in chronological order so it was easy to order them. With my first collection it was a bit harder, but as they were also autobiographical, I ordered them according to time, in three sections: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. I think it’s going to be quite hard doing this for my next collection, as there are a variety of themes and POVs, and I’ve written them over a long period of time.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love a poem to provoke a strong emotion in me, whether it’s happiness or sadness, it’s the intensity of the emotion that I like to experience. I recently read ‘Stand in the Light’ by Elizabeth Rimmer and it made me so happy and tearful I had to share it with people! So I sent it to my best friends and shared on social media. I loved it so much, and read it over and over. It was so full of hope, and light, but acknowledged the flaws in us as humans. It was really beautiful. I hope I can write like this one day, give people hope. Perhaps my writing will evolve like this, I hope it will, as I get older and perhaps have less of a need to examine my own life.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

Onions

First day of the year: a spill

of onions on the terracotta kitchen floor.

I stare at their brown skins, trying

to remember how they got there.

Last night my sister’s boyfriend

tried to hang himself. I kissed

my friend’s good-looking husband

on a boat. Our friend’s still asleep

in the sitting room. It’s half past three,

and very cold. The night storage

heater’s broken, and I’m short for the rent.

Although I want to want him,

I’m not sure anymore.

I chose this poem because I feel it is the heart of the collection: the beginning of a terrible year, although I don’t know it yet. Everything feels messy, and it’s going to get worse. The onions all over the floor sum up my life: a mess, but I don’t quite know how it happened.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

I’d be too scared to try and convince someone to read it! I’ve always been rubbish at promoting my work although I am getting better, you have to! But if I absolutely had to, I might say, (nervously) these poems could show you that we as human beings can get through anything. Although by global standards of suffering, the problems I faced could be described as ‘First World problems’.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

To be a poet is to tell the truth of me, and to hope this truth resonates with others. I’m a very open person and my poetry reflects this, and it enables me to say things I might otherwise struggle to say. What scares me most about being a writer is not getting where I want to be, which is successful, and receiving recognition, although even if I don’t quite get there, I will never stop writing, I will never stop being a writer. Recently I had a conversation with other writers about whether you are still a writer without readers. I said, Yes, you are. Obviously we want readers, but the act of writing is essentially for us, putting words onto a blank page to create something, to release something, to explore something, in the best way we can. What gives me the most pleasure is seeing the words on the page and thinking, Yes, I’m pleased with that, that’s worked (because it doesn’t always!). And of course publication or being placed in a comp. When I got the email through to say ‘Blinking in the Light’ had won a competition along with three other winners and would be published, I kept reading the email to make sure it was real. It was so exciting. Even though I’d imagined the poems being out in the world, I couldn’t believe it at first. After the high came a low point, when I thought about the impact the poems could have on people who were directly affected by the deaths that occurred. I really didn’t want to hurt anyone, but I didn’t feel I could withdraw the pamphlet. I do worry about upsetting people, especially my family and extended family, but I also need to explore things that have happened through my poems, and inevitably other people are involved.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I don’t think so, although I suppose in this case diaries helped shape the poems. Reading other poet’s work which I love helps because it inspires me. I suppose even reading fiction may help – I read a lot of novels.

What are you working on now?

Lots! I’ve nearly completed my first novel although I’m not quite happy with it so still playing around, I’m 50,000 words into my second, which decided to put in an appearance before I’d finished the first, like an insistent child saying, What about me? I’ve got lots of poems I want to pull together into a second full-length collection, and I have a number of short stories I want to put together into a first collection. I’m applying for grants so really hope I get one, so I can pay a mentor. I feel as though I’ve got as far as I can on my own – I’m largely self-taught – and want some professional guidance. I want to understand what I’m doing more, instead of just doing it and hoping for the best. I’ve got ideas for a young adult novel; a third novel; and future poetry collections (I want to use my diaries from the 1980s for these).

When a poet is writing his or first (or second or third) chapbook, the question often arises early: What's going to hold this mini-collection together? Sometimes, each poem has the color blue in it. Sometimes it's a narrative. In your case, you used the narrative angle extremely deftly. For me as a reader, I felt as though I was reading a story in verse, so multi-layered and yet also so clear (I didn't get confused with the different characters and poems shifting between events). Can you talk about using narrative as a way to unify the chapbook? And what tips (and things to avoid) do you have for poets looking to write a narrative chapbook?

I didn’t plan to write this collection so hadn’t thought about themes that might hold it together. It is very much a story, and that is often how I write poetry, as though I am telling a story, whether it be about my life or the lives of others. Possibly this is because I also write fiction, and am obsessed with stories, I don’t know! This is a hard question to answer as I tend to write very much from the heart, not the head, and never plan what I’m going to write in any detail. The idea forms itself in my head, I think, Oh, I want to write about that, and ponder on it for a few days, then sit and write and see what comes out. I guess I’d describe myself as an instinctive writer, in the same way that I’m an instinctive person – I go on feelings and emotions. As for tips to other writers – just listen to the essence of what you want to say. Don’t aim for clever tricks. Just let your voice speak, let the words form themselves. Then you can go back and play around with what you’ve produced.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

‘The Flying Man’ by Roopa Farooki. She is brilliant; I love her. I love the way she paints portraits of flawed characters and dysfunctional families so beautifully, and that her fiction is almost like poetry.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Jackie Kay; E E Cummings; Linton Kwesi Johnson; Mary Oliver; Derek Walcott…but there are so many more!

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

None – you asked loads of brilliant questions! Thank you so much!

***

Purchase Blinking in the Light from Cinnamon Press.

http://www.cinnamonpress.com/index.php/hikashop-menu-for-products-listing/poetry/product/191-blinking-in-the-light-louisa-adjoa-parker

Photograph: Maisie Hill Louisa Adjoa Parker is a writer of Ghanaian/English heritage who has lived in the South West of England since she was 13. She writes poetry, fiction and black history, and began writing to explore feelings of difference. Her first poetry collection, Salt-sweat and Tears was published in 2007, and she has recently had her pamphlet, Blinking in the Light, published by Cinnamon Press. Her work has appeared in various publications including Envoi, Wasafiri, Ink Sweat and Tears, Ouroboros, Closure (Peepal Tree) and Out of Bounds (Bloodaxe). She was highly commended by the Forward Prize. Louisa is currently working on two novels.

Photograph: Maisie Hill Louisa Adjoa Parker is a writer of Ghanaian/English heritage who has lived in the South West of England since she was 13. She writes poetry, fiction and black history, and began writing to explore feelings of difference. Her first poetry collection, Salt-sweat and Tears was published in 2007, and she has recently had her pamphlet, Blinking in the Light, published by Cinnamon Press. Her work has appeared in various publications including Envoi, Wasafiri, Ink Sweat and Tears, Ouroboros, Closure (Peepal Tree) and Out of Bounds (Bloodaxe). She was highly commended by the Forward Prize. Louisa is currently working on two novels.

Published on April 05, 2016 04:42

March 29, 2016

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Kelly Fordon

Kattywompus Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Kattywompus Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

The poems in this chapbook were all titled “The Witness” at one point and though I introduced more variety later on, it seemed natural to name the collection The Witness. It is still the title of eight poems in the chapbook and many more in the full-length collection. “The Witness” in these poems is a person who has observed the atrocities against children perpetrated by members of the clergy and is trying to come to terms with it.

Sammy Greenspan (the publisher at Kattywompus Press) and I were searching for the perfect image for this chapbook when I happened on William Cheselden. In 1733, William Chesleden published Osteographia, a grand folio edition depicting human and animal bones, featuring beautiful copperplate images, including playful skeletons, vignettes, and initials. Cheselden and his engravers, Gerard van der Gucht and Mr. Shinevoet, employed a camera obscura to execute many of the images and this one just seemed like the perfect image for The Witness, who has literally been shattered by what he has seen.

The three words to describe the chapbook: The Witness speaks.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

This chapbook was written in response to the testimony offered by members of the Survivor’s Network of those Abused by Priests (snapnetwork.org) and drew on some of my own experiences with the Catholic Church as well. Many of the poems are told from the perspective of a person who witnessed sexual violence and/or was a victim of it. This “Witness” is a very particular character, not a spokesperson for all victims by any means, just one person who cannot get over it.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

This collection was driven by obsession. I don’t want to go into much detail, but I had some personal experiences with the church scandals, and then I read the 10,000 pages of testimony on the snapnetwork.org website and also on the Center for Constitutional Rights website. The poems spilled out. The whole time I was writing them, I wanted to stop writing them. The voice of the witness was born of outrage. Somewhere along the line I realized I had enough poems for a chapbook and sent them to Sammy Greenspan at Kattywompus. She published my second chapbook, Tell Me When it Starts to Hurt, in 2013 as well.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

There are so many “Witness” poems I didn’t want to overwhelm the reader, so I tried to intersperse the poems written in that voice with other poems in order to break up the monotony. In this chapbook, I was very conscious of the subject matter and how it might affect the reader, so I ordered the poems with that in mind as well—shorter poems next to longer poems, Witness poems next to poems written from different perspectives, but I have to admit none are easy reading.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I am always looking for the turn in the poem; the place where something unexpected happens.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This is the first poem I wrote about this subject. It isn’t actually a “Witness” poem, but I think you can tell it is fueled by rage. I had just found out about someone within my extended circle who committed suicide in the aftermath of abuse.

THE VICTIM’S TESTIMONY

I’m stuck in this file cabinet.

Who wants to finger me?

My words are onion paper thin.

Easily crumpled, easily tossed.

In French class I say,

S'il vous plaît ne faites pas ça.

Shower me with holy water

and I shriek like Asmodeus.

The first robe is always white,

but the outer one changes

like his performance. It was purple

that day to remind us of our sins.

As if I could forget.

As if God could. The light

above my box is always red,

which means stop, a word

I use more than any other.

*Asmodeus: one of the seven princes of Hell most often associated with lust.

** S'il vous plaît ne faites pas ça translates: Please do not do that.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

I would say, “There are 10,000 pages of testimony by people who were victimized by Catholic clergymen. 10,000 pages. It boggles the mind.”

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I took a creative writing class with Laura Kasischke at the University of Michigan and she said that writers are the luckiest people in the world because everything that happens to us, good and bad, is material. We get to transform our lives into art and that gives life meaning. I feel that way about writing. It helps me make sense of the world, and even if I can’t make sense of it, it nudges me toward the light.

I am scared of writing about controversial topics.

I am scared that one day I will give in to that fear.

When I have been working on a poem or story for months and I just can’t get it right and then one day the solution occurs to me and it morphs from a problem I am trying to work out into a piece of writing I am proud of, that is a great day.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I love reading newspapers (especially the science section of The New York Times) and I often come up with ideas for poems after reading articles.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a full length collection of poetry and a novel.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Forest Primeval by Vievee Francis

Our House Was on Fire by Laura Van Prooyen

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Vievee Francis

Laura Kasischke

Laura Van Prooyen

Jamaal May

Tarfia Faizullah

Diane Shipley DeCillis

John Freeman

Keith Taylor

***

Purchase The Witness from Kattywompus Press.

Kelly Fordon’s work has appeared in The Florida Review, The Kenyon Review (KRO) and Rattle, among other places. She is the author of three poetry chapbooks and a novel-in-stories, Garden for the Blind, which was published by Wayne State University Press in 2015. She works for the Inside Out Literary Project in Detroit. www.kellyfordon.com.

Kelly Fordon’s work has appeared in The Florida Review, The Kenyon Review (KRO) and Rattle, among other places. She is the author of three poetry chapbooks and a novel-in-stories, Garden for the Blind, which was published by Wayne State University Press in 2015. She works for the Inside Out Literary Project in Detroit. www.kellyfordon.com.

Published on March 29, 2016 06:19

March 22, 2016

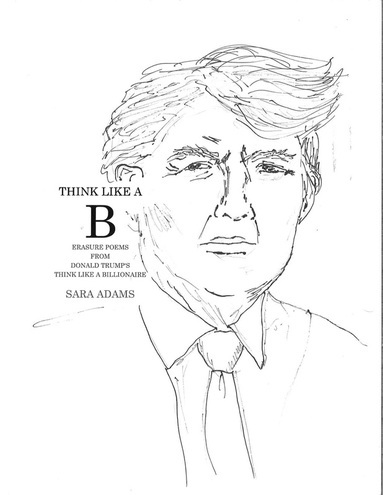

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Sara Adams

SOd Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

SOd Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your chapbook, what three words immediately come to mind?

First, I’d like to quickly explain the chapbook. Think Like a B is a chapbook of erasure poems from Donald Trump’s book, Think Like a Billionaire. I scanned individual pages from the book and used photo-editing software to "erase" most of the words and create my poems.

I liked the idea of a title that was essentially an erasure itself. “B” could mean a lot of things.

The cover was created by my bff, Jeremiah Xavier Avila (www.xavila.com). The approach was really Jeremiah’s, but I think it's perfect. My favorite part about it is that my words are reaching his ear.

Three words to sum up the chapbook: self-important, rude, and creepy.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I was curious to know what Trump’s advice for a fruitful life would be. I wanted to get inside his words, rip them open, and make something from the carcass. There's truth in the carcass.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I love this process.

I write erasure poems within very short chunks of time; it's like there’s a little bit of magic there, and phrases pop out at me, then it fizzles out within 10 minutes and all I can see is the words on the page in their proper order. Usually, a poem either comes together within 10 minutes, or it never comes together.

I sit down with the book and skim pages until I see a good word or sequence of words. I scan for other words and phrases on that page, and write them down in order. I work with all the possibilities of that page. My ideal is to create some kind of narrative, if possible, which is dramatically different from the meaning of the original text, but also responds to it.

With erasures, the absolute worst is when you find two really great sequences of words, but you can’t use both because of the order in which the individual words appear on the page. It’s aggravating. It’s heartbreaking. It’s like … 10,000 spoons when all you need is a knife. Or maybe it’s like a romantic comedy. Anyway, these are the poems that take more than 10 minutes. I have difficult decisions to make because everyone’s boyfriend material and I really want the knife but I can’t have it all.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I printed the poems out and shuffled them around many times. I was hoping to help the reader be ready for each poem right at the time it appeared. I feel like certain poems build an appetite and others satisfy it, but too much of the latter results in getting a little bloated. There’s a rhythm, I think. I tried to read my poems in order and pretend I hadn’t written them, and kept shuffling and re-reading until I thought, “Ahh, yes,” wiped my face with my napkin, and walked away from the table.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love when a poet expresses not knowing but, in the process, shows that they do have a deep understanding of something. I love when humility and wisdom intersect.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This poem is a core value disguised as a complaint disguised as a piece of advice/wisdom. It’s a demented proverb. This is definitely at the heart of the book.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

I would say that I have extracted and distilled all of Donald Trump’s wisdom into 13 pages.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I'll start with what scares me: hooking a poem then losing it because I reeled it up too slowly or too quickly, or a seal ate it, or I never had it to begin with. Being a poet is working toward being OK with seals, and delusion, and loss, and failure.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Think Like a Billionaire, obviously. I’d lend you my copy, but I tore a lot of the pages out.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Rumi, Robert Hass, Lorca, and tons of up-and-coming and experimental poets published by small presses and lit mags!

I cheated; sorry.

****

Think Like a B in PDF version is free online.

If you like physical objects, Sara Adams would love to send you a stapled booklet hard copy for $3 (including shipping). Contact her through her website, Www.kartoshkaaaaa.com, to arrange PayPal, venmo, or something!

$2 extra for each additional copy in same shipment! You can never get enough Trump!

($3 for initial shipment applies to U.S. Lower 48 only, but we can work something out if you're international/AK/HI!).

Sara Adams is a Montessori teacher in Portland, Oregon. Think Like a B is her first chapbook. She has two others forthcoming in 2016—Poems for Ivan (Porkbelly Press) and Western Diseases (Dancing Girl Press). Her work appears in lit mags such as DIAGRAM, tNY Press’s Electronic Encyclopedia of Experimental Literature, and Shampoo Poetry. Sara also co-wrote a full-length New Translation of Twilight, available at www.fredwardbound.com. Visit her online at www.kartoshkaaaaa.com.

Sara Adams is a Montessori teacher in Portland, Oregon. Think Like a B is her first chapbook. She has two others forthcoming in 2016—Poems for Ivan (Porkbelly Press) and Western Diseases (Dancing Girl Press). Her work appears in lit mags such as DIAGRAM, tNY Press’s Electronic Encyclopedia of Experimental Literature, and Shampoo Poetry. Sara also co-wrote a full-length New Translation of Twilight, available at www.fredwardbound.com. Visit her online at www.kartoshkaaaaa.com.

Published on March 22, 2016 04:42

March 14, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Tricia Knoll

Aldrich Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Aldrich Press, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each?

Ocean’s Laughter comes from a line in Pablo Neruda’s Book of Questions: "do you not also sense danger in the sea’s laughter?" This collection of lyric and eco-poetry summarizes my 25-year home ownership on the Oregon coast in a small town, Manzanita. I’ve seen the danger in the sea’s beauty – rising sea levels, winter storms, loss of bird habitat from human actions, the threat of major earthquake on the Cascade subduction zone, the erasure of the history of the First People from visible presence in this beautiful land. Then there are the sunny days of summer when there is no place on earth more beautiful to me. When wind whips you back to your true self.

Darrell Salk, my husband, took the cover photo. I asked him to crouch to get the dune grass, the mass of Neahkahnie Mountain on Manzanita’s north end, the sand, and sea.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I love Manzanita, Oregon. For 25 years, my vacation rental home there was the one stable place that stayed with me. The Oregon coast is both rugged with old growth and a place for joyous play in sand and waves. There's a magnificent recycling center. Night stars dancing on waves. I witnessed what has changed over that time and share thoughts on laws which allow driving on the beach, harvesting driftwood, and shooting off Fourth of July fireworks over marine sanctuaries. The book has a map showing where Manzanita is and a description of the town’s idiosyncrasies. It is vintage “Oregon coast.” Poetry of place.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I rewrite and rewrite. I work on the computer. I seldom open a file without changing something. Some of these poems go back to my early days in Manzanita.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

My process is somewhat like laying the pages on the floor, but I used an electronic table. I know the poems so well that I could see what needed to follow what. Some are chronological – like the poem I wrote about September 12, 2001. The world was reeling from the fall of the towers in New York. In Manzanita, the fog on the beach was as dense as I’ve ever seen it. Families were building sand castles. Basalt pebble windows. Gull feather flags. Moats and bridges. One after another up and down the six-mile beach.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

The unexpected turn. The metaphor that makes me say, I wish I wrote that.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

“Pocket Rocks” was the first of Ocean’s Laughter’s poems that was published. For decades my daughter and I collected smooth stones off the beach to put in the rock garden in my beach house’s backyard. A kind of beach combing on a long walk that yielded sandy pockets. She is now an assistant professor in eco-system ecology with a Ph.D. in geology.

Pocket Rocks and Fondle Stones

For GGT, geologist.

Her toddler's hand plucked up

the first fondle stones

as sparkles in salt water,

green or black basalt pennies.

We squirreled them in pockets

gritty with sand, pinched

them in place to pave

our garden’s path with rock money.

Hand warmers, flatnesses

and worry stones for a thumb’s ease.

She understands each,

veined or water tumbled,

like nothing else on earth, singularities,

jewels juxtaposed with scents

of barnacles, brine, kelp, sand, and sea.

Those pocket rocks grew

to bowlfuls; a cracked yellow

cookie mixing bowl, last of a graduated set,

stainless steel pressure cooker from Goodwill,

white enamel stewing pot.

I house old bowls

of bold stones. Mother keeper

of the rocks.

A hand need never be empty or alone.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

This poetry will bring the ocean wind into your hair. Perhaps that is what you need right now.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I love placing words together. No one likes rejection but I’ve written a poem about how I feel when poems come back to me, like a homing pigeon just rang a bell and it’s time for me to attend to the return. I love to have poems accepted by journals.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

My reading is eclectic. I read several daily science new feeds, lots of poetry, and non-fiction about environmental change.

What are you working on now?

I’ve almost completed a manuscript of poems and prose poems that I’m calling “How I Learned to be White.” It’s a reflection on racism’s impact on me, what I learned from my culture, family, and work. It includes excerpts from letters my my great-grandfather and other relatives wrote to my great-grandmother. The men all fought as Indiana regiment volunteers in the Civil War.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I love Ursula Leguin’s collection of poetry, Finding My Elegy. It collects her favorite poems written over many years. She’s an Oregonian. We’re familiar with her a science fiction; her reflective poetry is lovely. I’m more of a dog person than a cat person, but her poems on cats are lovely.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Issa

Pablo Neruda

Maxim Kumin

Ted Kooser

Nikky Finney

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Why do you write haiku every day? I love looking at what the world offers up each new day that is striking, interesting, unique. Today it was the very much alive earthworm squirming on my driveway after a hard rain. Sometimes those quick images become food for poetry although that is not the reason that I maintain this discipline. Gratitude is the motivator.

***

Purchase Ocean's Laughter on Amazon.

Tricia Knoll is a Portland, OR-based poet whose work has appeared in many journals and anthologies. Her chapbook Urban Wild (Finishing Line, Press 2014) examines how wildlife and humans interact in urban habitat. She has degrees in literature from Stanford University (BA) and Yale University (MAT). Until retirement she wrote communication materials for the City of Portland. Find her online at triciaknoll.com.

Published on March 14, 2016 17:30

March 8, 2016

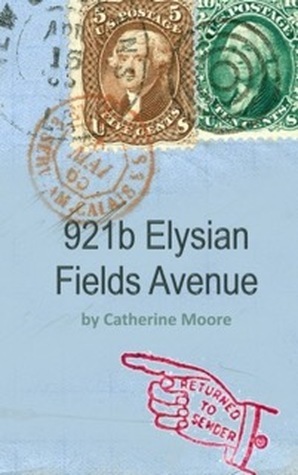

Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Catherine Moore

Kentucky Story Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Kentucky Story Press, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each?

The title, 921b Elysian Fields Avenue (RETURN TO SENDER), was created over time. As the narrative progressed I realized the character I was writing came from my past (see below) and I knew it was set in New Orleans, thus on Elysian Fields Avenue. Halfway through drafting the collection I decided the letters (poems) would remain unread. I saw them as a stack of weathered envelopes tied in twine and stamped (RETURN TO SENDER). The 921b is not homage to Sherlock Holmes but was decided after I toured Elysian Fields via Google Earth to find the location. I selected the perfect house for Daphne. As to the cover, the publisher, Ashley Parker Owens, and I had similar letter-related thoughts for the book cover so collaboration was easy and she designed it for the collection.

And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Epistolary Suspense Poetry.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

The chapbook is epistolary, using a series of letters to tell a love story. Through the use of personas, a battle between chastity (Daphne) and sexual desires (Apollo) is recreated in a modern context.

After attending a lecture on Fernando Pessoa, I was fascinated by his use of heteronyms (variety of personas) in his private love letters. That fascination served as the inspirational framework for this collection. This love story, set in the city of New Orleans, is told by way of an obsessed young man, Paul, who writes from different heteronyms (Apollo and Vern) to his desired Daphne.

I wrote the chapbook as prose poems, always intending it to be a hybrid narrative of prose and poetics. Through the letters a classic love triangle develops, although in this case the "triangle" only really involves two people. Paul is at odds with his heteronyms for Daphne’s attention. And will Daphne ever respond? At some point the reader may even consider the possibly that there’s just one person involved in the drama. I hope the ending resolves that.

The characters are attending college in New Orleans in the late 1980’s, a time period when I lived there, and I hope 921b Elysian Fields Avenue (RETURN TO SENDER) is as quirky and unpredictable as the city itself. The settings were harvested from my memories, reliable or otherwise. The characters and their stories are fictitious.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

This book originated from a 30 poems in 30 days effort. I convinced a fellow poet, Alfred Booth, to join me and we shared our daily poetry. Originally my concept was a female character writing in multiple personalities from two voices. The conceptual setting was also different.

After the second day of writing I realized (based on Alfred’s comments) that I might be writing in a male voice and that the character was from a novel I sketched out 20 years ago and never wrote. I just let it flow. Everyday starting with “Dear Daphne” and not knowing what came next. Alfred helped with suggestions “that’s not Paul’s voice, it sounds like Apollo to me.” One week into writing I sent him a message “I think there’s a third darker persona and his name is Vern.” It was unformed, free-wheeling, and fun.

When I went back to revise the series I showed another colleague of mine, Suzanne Ritcher, what I thought were a few of the best in series. She contacted me the next day: there should be more Vern, write more, what’s the backstory to this one, write more, and “send me the rest of the series.” This is very different than the way I typically work, but it was helpful to have readers check variation in voice. As I revised, Apollo became more lyrical and Vern the nearest to prose. Some letters seem more prose-like but are really poetry forms in disguise, such as Vern’s obsessive Valentine's note that is a villanelle.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems?

They are definitely not ordered in 921b Elysian Fields Avenue (RETURN TO SENDER) in the order I wrote them. Since I produced a new letter poem each day without pre-deciding on which voice, I often wrote in a blue streak of Apollo’s or Paul’s. It was after rounds of revision that I looked at sequencing. I laid out printed copies on the floor and read them in different orders. When I felt the narrative was correctly threaded, I made more edits for continuity of seasons and time progression. Then I thought each persona (heteronym) would date and use salutation in the letters differently, which really was the final step.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

The unexpected. Not just a volta or a twist, but a word that takes me to the dictionary, a moment or character that is unique, or fresh imagery and language that makes me read it in repeat.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The heart of book is obsession. The obsessive love of another. Obsessive internal dialogues. A desire to control obsessions. A need to explain all these obsessions to the one you love; from a letter of Apollo to Daphne--

You ask, this ruminative, how is this bodily felt? Crammed with life dust gathered under nails or born large and looming in the hip's gape? Within arms stretched reaching to hold nothing, or inside chambers waiting to yield everything? Resting sandhya between each passing hale, rising in rings above a collarbone hollow, or hidden inside coils under the helix after floating in a tear duct pool? I don't know its dwelling but it is fluent, in the providential retreat of swallow, in the fortune of oscillating membranes.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Have you ever loved someone who didn’t even care if you existed? Someone who would leave your heart-wrenched love poems unopened? Sadly, this may be your kind of read.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

What do Betty Boop, the blessed Virgin, Elizabeth Taylor, voo-doo dolls, Greek gods, 1950’s greasers, pilgrims, the band General Public, and Charon have in common? They all make a brief appearance within this collection. I am very eclectic in what I read and how I find inspiration. Along those lines, I like writing that combines the commonplace and the unusual.

What are you working on now?

I am working on (more) collections in hybrid forms— another chapbook, “One February,” that is a long narrative poem written in Ginsberg American Sentences and newer verse with Southern Gothic under tones. I’d say for now, I’m into longer thematic works that span a bridge between poetry and prose.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I recommend that writers submit work to literary contests that offer books in return for fees. This is how I discover gems like Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchins. I adore the way her poetry is rich in unobvious detail, such as how strangely green the grasses are at Auschwitz.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Elizabeth Bishop, Lucille Clifton, Mark Strand, Barbara Hamby, and Kay Ryan. Wait, Dorianne Laux and Tony Hoagland. Wait…

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

We know the poems are written in persona, so the “I” in the poems is not you the writer, but since you shared that you lived in New Orleans in this time period-- which one of these poems reflects yourself?

When I read the collection now, I think the letter poems of the Fourteenth of October 1987 and Feb. 9, 1988 most accurately reflect my feelings when delving into my memories of New Orleans. Both contain the bittersweet, that crazy passion of I hate this world and I love this world.

***

Purchase 921b Elysian Fields Avenue (RETURN TO SENDER) from Kentucky Story Press.

Catherine Moore is the author of Story (Finishing Line Press), 921b Elysian Fields Avenue (Return to Sender) (KYStory, 2015), and Wetlands (dancing girl press, 2016). Her writing appears in Tahoma Literary Review, Cider Press Review, Bluefifth Review and in various anthologies. She won the Southeast Review’s 2014 Gearhart Poetry Prize and had work included in The Best Small Fictions of 2015. Catherine lives in the Nashville area where she enjoys a thriving writer’s community and was awarded a MetroArts grant. Catherine earned a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Tampa. Visit her online at http://about.me/catherinemoore and at Goodreads.

Catherine Moore is the author of Story (Finishing Line Press), 921b Elysian Fields Avenue (Return to Sender) (KYStory, 2015), and Wetlands (dancing girl press, 2016). Her writing appears in Tahoma Literary Review, Cider Press Review, Bluefifth Review and in various anthologies. She won the Southeast Review’s 2014 Gearhart Poetry Prize and had work included in The Best Small Fictions of 2015. Catherine lives in the Nashville area where she enjoys a thriving writer’s community and was awarded a MetroArts grant. Catherine earned a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Tampa. Visit her online at http://about.me/catherinemoore and at Goodreads.

Published on March 08, 2016 04:20

February 29, 2016

Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Amelia Martens

Sarabande Books, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Sarabande Books, 2016 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

My husband (also a poet) read the manuscript and selected two lines from the poems that he felt would be striking titles. I have been reading chapbook manuscripts for Black Lawrence Press and I’m always drawn to titles that are odd—either long or very short or strange in some way. I picked this title because 1) I thought it would stand out in a list of submissions 2) it matches the prose poem format of the collection 3) it contains several ideas that are significant to the book (defense, imagination, landscape, domesticity).

The cover is the work of the marvelous Kristen Radtke (managing editor at Sarabande). Originally, I submitted a few collagraphs by Michael Crouse who taught printmaking at University of Alabama in Huntsville, which were beautiful, but not quite what the press had in mind. Once these ideas were turned down, I was totally open to what Kristen would create. I love how timeless the cover is and how the shapes, colors, and arrangement work with the poems on the inside. I’m super-excited to have such a beautiful book!

In three words: conflict, magic, geo-political.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I live in this world. My two daughters live in this world. Many of these poems were sparked by an experience with my girls or something my oldest daughter (who just turned 5!) said to me about death (Close your eyes momma. Just close your eyes. You are dying.) or life or how the world functions. I wrote these prose poems starting after the birth of my first daughter, so many of them deal with the conflicted experience of being completely relied upon by another human being and also knowing that we live in a world where other human beings are being blown up, tortured, and piled into mass graves. I am interested in the surreal state we have to put ourselves into so that we can get out of bed in the morning—who could really walk around “normally” if they actually faced the terrible ways humans treat each other and the rest of the planet.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I wrote these poems while my daughters slept, nursed, were trapped in the walker or bouncer, went to the store with their dad, or later—while they played together in the next room. I think this time constraint is why I have a collection of prose poems. The fluidity of this form, the narrative, the ability to get a draft or idea down quickly without getting hung up on the line break—I joke that I can write a prose poem in the time it takes for someone not to die in the next room. I write in our laundry room, which is right next to the kitchen—so I’m off to the side of being in the middle of the domestic action. I just kept writing a poem here and there and putting them in a pile on my desk until it seemed like maybe there were enough for a book.

I have to print everything out and revise by hand; the screen is deceptive for me. I also read everything aloud as part of my revision process (although I am notorious for putting words that I can not pronounce into poems).

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I re-read Jeffery Levine’s “On Making the Poetry Manuscript” and then I waited until my daughters were at preschool, so that I could spread everything out on the floor. I first sorted the poems into thematic piles and then I started picking poems up as I saw connections, in a sort of collage format—not too much of this or that in a row, poems that touched on the same idea but from different threads, etc. My book begins with an apology poem, which I did because it’s the poem that best introduces the threads that run thought the book, but also because I teach composition and tell my students never to begin with an apology. When Sarah Gorham called to tell me that my book had won the Bruckheimer, she mentioned that it was “intelligently ordered” and I am deeply proud of this compliment because for years I believed that I was not good at ordering my work.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I love a poem that can jump—that can move a great distance in short space; whether this is by image or by going from the large idea to the small or small to large. I love poems that feel “true” in terms of their insight about the human experience (think Ross Gay, Ruth Stone, Kay Ryan, Nikky Finney). I’m not a fan of artificial poems or poems that are overly abstract; the poem must come back to connect with me—it can’t just be sound or image or striking line breaks.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

In September 2011, I attended the Kentucky Women Writers Conference (which is amazing in itself but also amazing in that my husband came and took care of our infant who I nursed between conference events) and had a workshop with Aimee Nezhukumatahil. In that workshop I shared a brand new poem entitled “A Hundred Miles From the Border”. The reaction of the workshop to this poem told me that I was on to something and I should try writing a few more of these Jesus poems, which became one thread in the collection. The poem first appeared in The Chattahoochee Review in 2012, along with “In the Land of Milk”, which was the first poem I wrote that is in the collection. With some revisions since then, here is how the poems appear now in the book:

A Hundred Miles From the Border

Even Jesus knows it takes three Americans to do the work of one immigrant, so he’s farmed out the labor.

Now poor boys from Mexico City stand on the assembly line, hot irons in their hands, and brand the face of the Virgin onto grilled cheese sandwiches, mud flaps, and the backs of lace curtains.

Soon the new wing will open up and Jesus will expand his operation; he’s slipped St. Peter a little something on the side, insurance against star-chested archangels riding up in a flurry of lights.

Since the installation of the air conditioner, the boys don’t mind being paid in Hail Mary’s and signed notes for salvation. They work mostly by candlelight, branding to the murmurs of Jesus as he works his rosary like an abacus.