Carpe Noctem Interview With Meg Eden

NEON, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

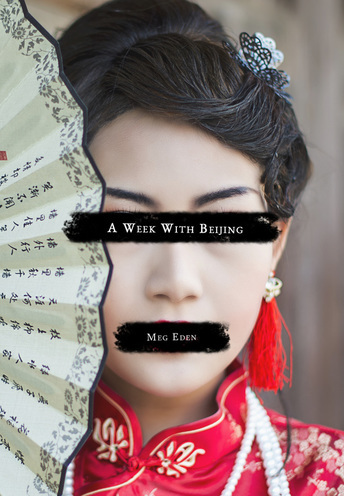

NEON, 2015 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

Title: Initially the poems were just narratives about my experience going to Beijing in late 2005. However, as I edited the poems, Beijing was no longer the landscape for my poems, but a character I was interacting with. So when that transformation happened, it made sense for the poems to be “a week with Beijing” as opposed to “a week in Beijing.”

Cover: My editor at NEON, Krishan, gave me a few image ideas for the cover. I really liked having a female in the image, and I really wanted some sort of censorship to happen in the cover, as the poems confront the silencing Beijing put upon its citizens before the Olympics (and beyond). So with the image of the girl, we decided we could censor out her eyes and mouth and put the title there. I’m very happy with the end product.

Three-word summary: personified political travelogue.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I wanted to recreate the culture shock and exchange I experienced travelling to Beijing. Most of the trips I’d been on before were very tourist friendly. Everyone was welcoming and provided a “dressed-up” version of their culture to satisfy our consumerism. But when I went to Beijing, the city was “still putting on its makeup”: it was building the Olympic arenas, ripping down the historic Hutong regions, and it was the dead of winter so there were few tourists to cater to. In fact, when we first landed, our taxi driver first said, “What are you doing here? It’s not the Olympics yet.”

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Once I had the idea of exchanges with an anthropomorphized Beijing, the poems came out easily. Revision strategy? I read through all of them in one sitting, make a couple changes at a time, and do that several times.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I think because this was a narrative experience, I tried to create a narrative arch with this collection: set up the situation, heighten the tension to a climax, and (sort of a) resolution.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

For me, a poem needs to haunt the reader. So I look for an image, a moment, that surprises and possibly disturbs me, but it makes me think longer and deeper about a situation. This is both in how I read and write.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

This is one of my favorite poems to do at readings. I think it paints a complexity for Beijing “coming of age” for the Olympics. It’s one of the later poems I wrote for the collection.

Beijing Explains Her Twelve Year Old Gymnast

She isn’t twelve, she’s sixteen.

Her name is He Kexin. She was in

the Olympics before but now

is retired; too old.

No one believes me—you think

we want to look so young?

That we don’t want American

breasts, full Western hips? And lips?

I have no daughter, but if I did

she would fly like He. She would live

in the air, and only come down

to eat moon cakes and taunt us.

She would be afraid of no men,

and no men would enter her.

Her body would be tight

like a branch, unbending

but beautiful—no one would

educate her, she would sing

too loudly. She would not be known

by name, but by the way her legs

whip through the air like a bird.

The way she vanished so young

without demands, without fathers

to condemn and harness her wildness.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Probably something to the effect of: I’d bet you can actually read these poems and understand them (and maybe even enjoy them!). I seem to encounter a lot of people, who in response to me saying that I’m a poet say, “Oh I don’t read poetry. I can’t understand it.” As a rather narrative poet, this aggravates me to no end—what are English teachers making their students read? Whatever it is, it needs to change, because it’s scaring everyone away from the world of poetry!

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I could say a lot on that—but in short, to me being a poet is being a witness to something intimate, personal—and in many ways spiritual. What scares me most about being a writer is being a poor or unfair witness. What gives me the most pleasure is to testify to something in a way that's pleasing in both craft and content, and that provides a turn of surprise.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I find everything as fuel for my poetry. When I was working in scientific research, scientific articles provided inspiration for poems. Now, I’m reading quite a bit of academic articles for literature in translation. Writing-wise, I also write fiction, so everything I am reading and writing may return back into my poems.

What are you working on now?

I have a novel coming out in 2017, and am trying to figure out which novel to work on next. I’m also working on a full length manuscript of poems about the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

Just finished Jane Shore’s That Said, Susan Morrow’s The Dawning Moon of the Mind, and C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, which were all amazing. Also reading Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokemon by Joseph Tobin which—for anyone of my generation—is a fascinating read, and Sarah Well’s Pruning Burning Bushes.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Ocean Vuong, Naomi Shihab Nye, Patricia Smith, Danez Smith, April Naoko Heck.

***

Purchase A Week With Beijing.

Meg Eden's work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Poet Lore, and Gargoyle. She teaches at the University of Maryland. She has four poetry chapbooks, and her novel Post-High School Reality Quest is forthcoming from California Coldblood, an imprint of Rare Bird Lit. Check out her work at: www.megedenbooks.com

Meg Eden's work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Poet Lore, and Gargoyle. She teaches at the University of Maryland. She has four poetry chapbooks, and her novel Post-High School Reality Quest is forthcoming from California Coldblood, an imprint of Rare Bird Lit. Check out her work at: www.megedenbooks.com

Published on June 20, 2016 04:45

No comments have been added yet.