Heather King's Blog, page 30

November 7, 2022

OBSESSED BY THE SPIRITS OF THIS AGE

Still dealing with The Ground Squirrel. The good news is that I’ve managed to wrest an essay out of it–stay tuned.

October was all St. Thérèse of Lisieux, all the time. A couple of podcasts I don’t think I posted:

AUGUST 14, 2022

“Barriers to Receiving Love,” Podcast with Mary Jo Parrish of Kingdom Builders, Fort Wayne, Indiana, with a focus on the spirituality of St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

October 30, 2022:

Podcast with NOMAD: FAITH, DOUBT & REIMAGINATION

“The Little Way: The Spirituality of St. Thérèse of Lisieux

I’ve embarked on nine months of the Ignatian Exercises, and it seems I am ready for this particular adventure. What is holding me back from giving myself FULLY? What are my “possessions,” as in the Parable of the Rich Young Man (Matthew 16:19-22), that I simply can’t or won’t give up? The best I can figure my “possession” is my will: my schedule, my need to “give a good account of myself (by MY lights) at the end of the day, my need to be right, my (pride-based) very low tolerance for being “bored” or “annoyed,” my comfort, my rest, my way…

Meanwhile, I’ve gone back to Caryll Houselander, and am re-reading Maisie Ward’s That Divine Eccentric. I find it very encouraging that Caryll was so sharp-tongued (suffering reams of remorse over it), so loved a “Rabelaisian” story, was under certain circumstances so full of fun that many people suspected her of being a hypocrite and that her so-called faith was a sham.

Awhile back, I was pondering on how Jesus said Blessed is he who brings forth from his storehouse both the old and the new, and how “conservatives” in the Church want to go back and live in the past, while “liberals” want to erase the past.

Here’s Caryll Houselander, writing back in the ’40s or so, with insights that are still relevant today, if not more so:

“Some people cling to what is past; some, the fewer and braver, face the future; but to live harmoniously in the present is an almost superhuman task.

The modernist writers are not the contemptible egoists which they are too often supposed to be. They refuse to write anything which is not an integral part of their own experience, and most of them have no experience of the Faith as we understand it. The problems tormenting those of the modernist sort outside the Church are a thousand times more terrible than those within.

My position is that I am obsessed by the spirit of this age, with all its faults I love it and believe in it.

I believe that it is the most serious duty I have, to see, to recognize Christ in it and to go on, never to go back; that alll our modern inventions and conditions are to be used, cleared of abuses and lifted up but not swept away, that compromise with the present and a looking back to the past is a sin.

I find no sympathy with this view in the thought of my fellow Catholics, who seem to me to be always striving to return to the past and to set fierce limitations on the use of the present.

I find in this attitude a deadlock, a deadening and a choking of effort.

I do not trust myself to stand alone, I will not range myself amont those who, though they clearly share my desires, do not share my faith in Christ.

Consequently I am tortured.

I desire supremely and above all to be in perfect harmony with the whole world.”

My position is that I am obsessed by the spirit of this age, with all its faults I love it and believe in it.

That’s my position, too, or at least I want it to be.

On that note, my friend Rita sent me this excellent National Catholic Register piece yesterday, entitled “Polarization in the Church: How Can It Be Overcome?”

“Polarization has indeed been a painful wound and, frankly, a scandal, which has greatly hampered the mission of the Church in our time”…

“Is orthodoxy in and by itself what Christianity brings to the world? In fact, one could argue that our problem today is not so much a mere rejection of truth, but that truth and life are divided. Either life is affirmed as the primary value, or truth is affirmed in the abstract, but has a hard time becoming life, being verified as truth in experience“…

“At the beginning of Christianity, Jesus did not primarily propose a set of doctrines or a list of moral principles. Primarily, he proposed himself as “the Way, the Truth and the Life.” The disciples did not just meet a teacher and a moral exemplar; they met God-made-flesh.”

So how are we encountering Christ today–in our own lives, in the people around us, in the world as it is? Could we articulate our hope and joy, in the midst of uncertainty and suffering, in words a “simple” fisherman could understand?

November 4, 2022

VIVA MAESTRO!: COMPOSER GUSTAVO DUDAMEL

Here’s how this week’s arts and culture column begins:

Viva Maestro!, a 2022 documentary written and directed by Theodore Braun, is a paean to the LA Phil’s own Gustavo Dudamel.

Except he’s not just ours—far from it. He’s the director of the Paris Opera, music director of Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra, and a world-wide ambassador for the unifying, transcendent power of music.

Dudamel, a native of Venezuela, came up in El Sistema, the publicly financed, arts and community-building classical music-education program founded in 1975 by Venezuelan educator, musician, and activist José Antonio Abreu (1939-2018).

In fact, the documentary is also a paean to Abreu and the electric spirit and sense of responsibility that he passed on to one of his star pupils. Says Dudamel: “Abreu helped me to understand the universe of possibilities and how to use those possibilities to do something special.

“Wunderkind!” “Conductor of the People!” “Rock Star!” run the headlines.

READ THE WHOLE PIECE HERE.

October 28, 2022

DEAREST SISTER WENDY

Hello, people. I have been a little out of commission as of late, in large part due to a little situation with ground squirrels (oak trees don’t grow in Tucson so the squirrels here live underground) who made an extensive warren as it turns out directly beneath the floor of my bedroom, bathroom and office. And kind of made its/their way through the walls. Sleep was a teeny bit difficult, as was breathing normally, going about my day with a heart beating at the speed of a hummingbird, et cetera.

I had to clear out for a couple of nights, just to get my bearings, but after a visit from the guys who take care of such things, am back home, fingers crossed.

I know people deal with far worse situations, but I would beg your prayers.

Here’s how this week’s arts and culture column begins:

Back in the 1990s, Sister Wendy Beckett (1930-2018), a contemplative nun and consecrated virgin, delighted audiences world-wide with her lively BBC documentaries on the history of art.

Born in Johannesburg, she joined a teaching order in 1946, and then earned a degree in English Literature at Oxford, graduating with highest honors.

After teaching in South Africa from 1954 to 1970, she suffered a physical and emotional collapse and was granted permission to return to England.

There she stayed for decades on the property of the Carmelite Monastery in Quidenham, Norfolk, first in a caravan; later in a small room. Her true vocation was to take place in silence and solitude. She prayed for seven hours a day.

READ THE WHOLE PIECE HERE.

October 21, 2022

THE CASE AGAINST THE SEXUAL REVOLUTION

That got your attention, I bet!

Here’s how this week’s arts and culture column begins:

Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution promotes itself as a “counter-cultural polemic from one of the most exciting young voices in contemporary feminism.”

Hilariously—and encouragingly—much of it could have been written by a straight-up Catholic grandmother—or a human being of either gender and any age with a modicum of common sense.

Perry, a London-based secular writer and New Statesman columnist, proposes a new sexual culture built around “dignity, virtue and restraint.”

Well, amen. Chapter titles include “Sex Must Be Taken Seriously,” “Men and Women Are Different,” “Loveless Sex Is Not Empowering,” “Consent Is Not Enough,” “Violence Is Not Love,” “People Are Not Products,” and—miracle of miracles—“Marriage Is Good.”

READ THE WHOLE PIECE HERE.

October 16, 2022

MIDWEST AUTUMN

ST MARY’S RIVER, FORT WAYNE, INDIANA

ST MARY’S RIVER, FORT WAYNE, INDIANAI am having adventures quicker than I can write about them.

Two weeks after the fact, here are a few pix of my trip to give a talk in Fort Wayne, Indiana, on the October 1 feast day of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, and thence on to Lake Forest, Illinois, with side trips to downtown Chicago, Oak Park for a tour of the Frank Lloyd Wright home and studio, and Libertyville to the St. Maximilian Kolbe Shrine and a walk around the lake at the adjacent Mundelein Seminary.

I was insanely graciously, luxuriously, meticulously, hosted. I had Lou Malnati deep-dish pizza and a hot dog, swatched in acid-green relish, from Porfirio’s.

I walked along the banks of Lake Michigan.

I saw Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks” at the Art Institute.

And most importantly and notably–I made a new friend.

LURIE GARDEN, MILLENIUM PARK, CHICAGO

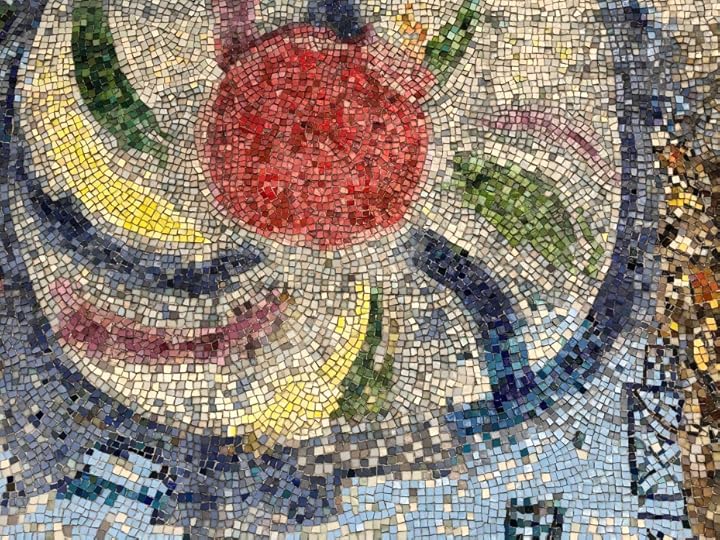

LURIE GARDEN, MILLENIUM PARK, CHICAGO “FOUR SEASONS,” PUBLIC SCULPTURE, MARC CHAGALL,

“FOUR SEASONS,” PUBLIC SCULPTURE, MARC CHAGALL,DOWNTOWN CHICAGO

GROUNDS OF MUNDELEIN SEMINARY

GROUNDS OF MUNDELEIN SEMINARY MIDDLEFORK SAVANNA, LAKE FOREST, ILLINOIS

MIDDLEFORK SAVANNA, LAKE FOREST, ILLINOIS

October 14, 2022

THE TRANSUBSTANTIATION

Here’s how this week’s arts and culture column begins:

“For some extraordinary reason, there is a fixed notion that it is more liberal to disbelieve in miracles than to believe in them. Why, I cannot imagine, nor can anybody tell me. For some inconceivable cause a ‘broad’ or ‘liberal’ clergyman always means a man who wishes at least to diminish the number of miracles; it never means a man who wishes to increase that number.”

–G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

The Church teaches that “the Eucharist is ‘the source and summit of the Christian life.” Without the Transubstantiation, Christ is but a symbol. The Crucifixion and Resurrection are but metaphors. Communion is virtual reality, not the Real Body and Blood of Our Lord.

Yet a 2019 Pew Research Center survey found– distressingly, astoundingly—that under a third of U.S. Catholics believe that “during Catholic Mass, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Jesus.”

READ THE WHOLE PIECE HERE.

Here’s a related YouTube I worked up several weeks ago.

October 7, 2022

MARIA SIBYLLA MERIAN, SCIENTIST AND ARTIST

Here’s how this week’s arts and culture column begins:

Seventeenth-century naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) was a woman way ahead of her time.

Boris Friedewald’s “A Butterfly Journey” charmingly recounts the story of this astonishing scientist and artist. The book includes more than 30 full-page color copper plates of Merian’s gorgeously detailed work.

Born in the German town of Frankfurt am Main to a family of engravers, publishers, and printers, young Maria was surrounded from an early age by illustrated books about exotic travel, New World landscapes, sumptuous gardens, and still lifes of fruit and flowers.

READ THE WHOLE PIECE HERE.

October 5, 2022

REHABILITATING ST. THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX

Here’s how this week’s arts and culture piece begins:

St. Thérèse of Lisieux, 19th-century French nun, lived in an era when women had far fewer rights than today, when women were far less recognized as “equal” to men, when women had little to no ‘voice’ in the Church.

Yet reading her today, one is struck by her freshness, vigor, energy. Unlike the almost universal contemporary feminine voice, in and out of the Church, Thérèse is not oppressed. Thérèse is not aggrieved. Thérèse is not a victim.

Thérèse had one burning focus, one goal, one desire. She willed the one thing: to become a saint.

READ THE WHOLE PIECE HERE.

September 29, 2022

EVERYTHING PROFOUND, PART III

In case you haven’t been following along, here’s Part I and Part II of an essay about our search for home, starting over, and our tragicomic earthly pilgrimage called “Everything Profound Moves Forward in Disguise.”

Here’s the final installment.

I know a grand total of two people here; Johnny, a singer-songwriter, and his wife Felicia, a nurse-practitioner (their first-grader son Soren technically makes three). Dear friends in their early 40s who I met through recovery, they also happen to be Catholic.

But that’s it. I have no other connections or ties to Tucson. Pushing 70, I’d be starting from scratch. I’d have to find a place to live. I’d have to figure out how to move. I’d have to change health insurance, car registration, libraries, grocery stores, hair salons, movie theaters, libraries. I’d have to adjust to a new climate, zeitgeist, way of life,

I’d have to find friends, fellows, people of some kind. I’m an introvert, but I also love people, long for people. It took me years in LA to learn how to balance that longing with the silence and solitude I need: not only to live, but to write.

And it would probably take me years again.

There’s all that, plus leaving for good would be wrenching. It’s not like I’m contemplating a move to some wilderness outpost, or even to a foreign country. I’d be going 500 miles, a mere seven-hour drive. But if I’m a low-level nomad, I’m also a heavy-duty nester. My apartment is filled with flowers, prayer cards, fairy lights, pottery, candles, icons, and rugs that I’ve arranged just so. How to leave the Meyer lemon trees, the rosemary bushes, the old-growth camellias, the wild fennel? How to leave the huge native California garden I’ve created, crammed with sages, buckwheats, toyons, and a Western redbud?

Say what you will, the Golden State is gloriously diverse, bountiful, sunny. It has beaches, mountains, deserts, oceans, forests plains. It boasts palm trees, rose gardens, In-N-Out burger, surfers, movie stars, artists, storytellers, and serial murderers. It’s driven by an ostensibly laid-back but unquenchable, ever-exuberant energy. There’s a reason so many millions of people have wanted to live here, move here, live here, die here. Love it or hate it, California has cachet—and LA has cachet-plus.

For thirty years, wherever my road trips have taken me, no matter how many or how few miles I’ve driven, on the way back my heart has skipped a beat at the green freeway sign: “Los Angeles,” with an arrow beneath it, pointing home.

***

Saturday night I walk to Vigil Mass at Santa Cruz, a church sits on the edge of the ghetto and resembles a hulking, slightly lopsided, Moorish wedding cake.

Built in the early 1920s, it’s the oldest mud-adobe structure in Arizona, and that the upkeep for such a gigantic space clearly far exceeds the parish’s means is clear.

Inside, the statues of angels and saints look to be molded from papier mâché by kindergarteners: no matter. The priest’s homily goes on way too long: no matter.

I’m a stranger here: clothes that stick out, the wrong race, vaguely unwanted in that way that aging women, traveling by themselves, are always vaguely unwanted: no matter.

Never do I feel more at home than in an “ordinary” Mass: young girls fresh from the beauty parlor, construction guys just off work, harried mothers with frail abuelitas in tow, mewling infants.

Mass for me is part of staying at my watch. Christ stayed at his watch, and the people before whom I bow are those who stayed at their watch, too: the martyrs, the saints, and the artists who laid down their lives for their work—Margot Fonteyn, van Gogh, Beethoven; Billie Holiday, Dostoevsky, Caravaggio—the dancers, painters, writers, and musicians who have shored me up all my life.

If ever you want your faith in humanity restored, in fact, attend a Mass and study the faces of the people as they return to their seats after Communion. They’re the faces of people who have just made love, or been told they’re about to have a baby.

I, too, return to my pew carrying a secret inside. “Lord I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.” In order to be healed, you have first to be sick; to be wounded.

Friend to all misfits, outcasts, malcontents, neurotics and obsessives, Christ is in solidarity with every little action we take toward beauty, truth, and light. He died to encourage us not to give up, not to take the easy route, to do what’s scary for us even though it might not be scary for anyone else, to keep on going even if no-one else notices or cares.

By the time we emerge, it’s dark. The stars are shining. The courtyard is lit by pale green string lights that glow against the inky sky. Traffic roars by on 22nd Street. I carefully pick my way across the intersection, thinking of the pedestrians who must surely have been killed doing likewise.

If I myself were hit by a car, no-one but God would know that after taking the Eucharist just now, I had prayed, “O good Jesus, accept this Holy Communion as my Viaticum, as if were this day to die.” Viaticum: food for the journey.

Jean Sulivan (1913-1980), French priest, wrote a number of novels in the ‘50s and ‘60s critical of clericalism. The protagonist of The Sea Remains (1964) is a cardinal who, weary of pomp and perks, leaves Rome and then has a conversion: to humility, to love.

Even so, he doesn’t want to do away with the Church; rather, for the first time, he sees through to her mystery. The glitter is somehow both necessary and a veil: without the tawdriness, the hypocrisy, how would we recognize ourselves? Without the pomp, however risible, how would we reach for something higher: something harder?

“Parades, publicity, all the forms of propaganda and spectacle—he’d give them away to the devil if the devil would take them. But…the gospel couldn’t be delivered to the world in its pure essence. If the soul were without a body, there would no longer be a soul. A love without some degree of opaqueness would no longer be a tangible love. The Church had constructed its body, the body that was its shell, which had grown larger century by century. The fire was not blazing up because the walls were too high, the shell too thick. But perhaps the fire should not be allowed to burn with too high or bright a flame. Otherwise the crowds would come, fascinated like flies around a lamp; they would clap their hands, be overly receptive to miracles but blind to the heart of things, wanting the resurrection, of course, but certainly not the agony or the death. The Church, with its ramparts, its possessions, its works of art, the Vatican, the cardinals—none of all that existed for itself but rather so as to permit a revelation in human consciousness…In any case, it was necessary to pass through scandal and overcome the obstacles. But total purity would be yet a greater obstacle. Had I read Nietzsche? ‘Everything profound moves forward in disguise.’”

***

I’ve finally finished off the last of the food I brought from home—wizened tomatoes, a limp bunch of Tuscan kale—and venture out for supplies. I discover The Time Market and stock up on olive oil, mustard, cured meats, cheese, tortellini, and bread.

Then I wander the dreamy streets north of University Boulevard: old bungalows with generous yards, screened-in porches, meandering gardens. The air is clean, the air balmy, the sky deep blue with masses of shape-shifting clouds. I’ve always loved the desert, unpretentious yet mysterious, including—in fact especially—the heat. One of those annoying people who’s always cold, my bones have never fully unthawed from the 38 winters I spent in New England.

I could so live here! The median home price is $250,000. Even I, on my self-employed writer’s income, could possibly afford to buy a house here (that would be a first!)—and at the very least, rent.

“Do you know the origin of that word ‘saunter?’” mountaineer John Muir once asked an interviewer. “It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, ‘A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’”

In the early 90s, suffering from cancer, novelist Jennifer Lash (1938-1993) took off, alone, for the Camino de Santiago.

On Pilgrimage is her account of that journey. She’s in too much pain to walk, so she takes trains, buses, taxis. She’s uncertain whether she believes. She’s open. She’s a seeker: observant, wry, deeply sensitive to nuance, beauty, the emotional temperature of any given place.

In one sublime passage, she observes:

“While [Sister Agnes of the Taizé community and I] were standing together at the back of the basilica [of St. Michel D’Aiguilhe in Le Puy, France], there was suddenly a tremendous gust of wings. Sparrows and pigeons were continually flying around, but this gust of a bird was mighty and different. We looked up, and there, high above the narthex was the unmistakable, compelling face of a barn owl. Again and again it flew and paused, frantically crashing its white body with terrible hopelessness against the dusty windows. Every so often it would fly the whole length of the church only to soar up again into another barrier of light. I cannot describe how unbearable it was to follow the flight of that bird, knowing that we were quite incapable to give it its freedom. There were holes and spaces, if only it would see them. Each time it failed, the pause and stillness became longer, and the fearful despair of the bird felt greater.

We left for the library. We couldn’t bear to be there. Later, the whole experience haunted me. The gaze of that particular bird is so involving. I suddenly thought, what if God witnesses in every man a divine spark, which flies within us blindly, like that bird, crashing in terror, punched and pounded from wall to wall, blinded by obstacles and dust, and yet, God knows, that there is a way for natural freedom and ascending flight. What an extraordinary pain that witness would be.”

***

As often happens, a couple of people have emailed this morning asking for prayers. So later I walk through the Barrio saying the Glorious Mysteries of the Rosary.

If there’s one way I know my life has borne fruit, it consists in the people who have read my work and who write to, email or call me: housewives, monks, single fathers, nuns, hermits, women in desperately unhappy marriages, women in or out of desperately unhappy marriages who are crazy in love with a priest. Priests. People who’ve been sexually, emotionally or physically abused.

People who are pissed at the Church, pissed at their mothers, fathers, siblings, children, neighbors, boss, elected officials. People in sorrow, grief, doubt, bewilderment, rage. All of them nonetheless burning, as Christ, did for the Kingdom of God to be kindled.

I’m spouseless, childless, aging, not rich, not famous. I have no social status. My poverty is precisely what people are drawn to. They’re not threatened. They’re not afraid to approach.

As Emily Dickinson wrote to a grieving friend: “The crucifix requires no glove.”

***

Cesare Pavese died at 42, a suicide. Discouraged over the political situation in Italy, suffering from depression, and crushed by a brief, failed love affair with an actress, he rented a hotel room and took an overdose of barbiturates. “Death will come and she’ll have your eyes,” he wrote in one of his last poems.

My own romantic obsession almost killed me. Every minute of every day—for years—was agony. I tried everything: 12-step groups, Confession, spiritual direction, endless examinations of conscience and moral inventories.

I felt like I was being flayed. My feet broke out in a form of eczema so severe that the doctors as a last resort suggested chemo.

This was over a guy, by the way, who I never even kissed.

Even as I underwent this harrowing of my soul, I knew the experience was essentially religious. Even in my bewilderment, I “trusted” somehow. I suffered through depression, humiliation, a sense of bewilderment and betrayal and absurdity. I suffered through the sense that my work and my love were going for nothing; the fear that I was not only a failure and a reject but crazy. I suffered, of course, a broken heart.

But never for a second did I think I would have been better off had I been able to “breathe through” or “go with the flow” or “dance like no-one was watching.”

“To be sure,” Victor Frankl wrote, “man’s search for meaning and values may arouse inner tension rather than inner equilibrium. However, precisely this tension is an indispensable prerequisite of mental health…I consider it a dangerous misconception of mental hygiene to assume that what man needs in the first place is equilibrium or, as it is called in biology, ‘homeostasis,’ i.e. a tensionless state. What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for some goal worthy of him.” [1]

At last, after what seemed like a cruel and impossible amount of time, the obsession lifted, that particular tension dissolved, and I emerged: my personality intact, but my will and my inner equilibrium transformed.

Mine is a life practically no-one would want. I eat alone, work alone, sleep alone. But along with the ragpicker kid in the Mumbai undercity, I saw that my poverty was in a sense my wealth: my narrow, semi-mutilated existence a thing of strangeness and beauty that mattered absolutely, even if to no-one but me.

When the dust settled, I saw also that to follow Christ creates an irrevocable divide. It requires a decision—a cut—the most decisive, complete, and permanent cut of all. “My kingdom is not of this world,” he said, and much as you love the world, you’re increasingly in the world but not of it. Your exile is increasingly complete.

You follow a completely different star. You can interact with any number of different and varied individuals and groups of people, but at a certain point, you have to withdraw in a way, to your Inner chamber, where all the true, hard work takes place.

I’d wanted to span two worlds. I thought I could belong exteriorly to a community that was secular, godless—creative, “fun”—and still maintain a private, inner life of Mass, contemplation and prayer. But I hadn’t been able to split myself that way. I couldn’t serve two masters.

I saw I’d always been meant for the cloister; for a vocation of prayer that naturally embraced celibacy. Not because I’m too bitter or dysfunctional for intimacy—I was married for 14 years and in many ways loved it. But marriage wasn’t my vocation. Marriage wasn’t how I was meant to bear fruit.

I kept thinking of a former nun with whom I’d stayed on my cross-country pilgrimage, a consecrated virgin[2] who ran a place called the Franciscan Appalachian Hermitage where she rented out cabins for twenty bucks a night. “I know it sounds strange,” she’d once told me. “But one man wouldn’t be enough for me. I want all! I want Him!”

For my own part, the station of single, celibate laywoman that emerged from that long dark night suits me down to the ground. I’m doing neither more nor less than any other single person in the Church is called to do, but that I’m able to embrace celibacy with a sense of humor and a capacity for surprise—that I see it as a gift—ringsof the miraculous.

That doesn’t mean I’m euphorically happy all the time. As St. Thérèse learned by the end of her short, pain-filled life: “There are no raptures, no ecstasies: only service.”

On the other hand, I also live, on some level, in a permanent sense of stupefied wonder, of crazy joy.

I still want Don Quixote to adore Dulcinea but I also realize that to fritter away my life pining for and fantasizing about the impossible is an offense to love: ridiculous in the wrong way. My passion hasn’t diminished one iota: rather, it’s been channeled.

Pavese, God rest his soul, jumped the tracks. He took all the pills (literally) at once. He missed what was right in front of him: the slow, excruciating dismantling of the ego; the gradual, bit-by-bit severing of earthly attachments. He forgot that everything that happens to us is extraordinarily important—especially the pain.

There is only one way through this vale of tears. Minute by minute, you suffer through: wasted, half-crazed, eyes wide open, without anesthesia. You continue to stare—with a frantic intentness—outward.

***

The day before departure, I sit out one last time on the yellow glider, gazing out over the horizon

How can this all end?: the long shadows cast by the saguaro, the drunk guy ambling down the street playing a recorder, the UPS man yelling, “Package!” followed by a thump on the front stoop.

My addict psyche causes suffering, “but total purity would be yet a greater obstacle.” The part of me that can’t waste a morsel of food is the same part that weeps at the hummingbird’s magenta throat. The part that can obsessively fixate on a human being is the same part that’s ablaze with divine longing. The part that can’t sit still is the same part can’t wait to get out of bed each morning: that’s alive, that’s excited, that rants, rails, exults, and cracks up laughing with equal intensity.

I wouldn’t have it any other way. The poor-in-spirit, rich-in-tragicomedy pilgrimage will continue, if I have anything to say about it, up to my last tortured, gasping breath.

In Robert Bresson’s film A Man Escaped, the protagonist Fontaine is a member of the French Resistance. “Death in itself I could accept;” he observes from prison, “but I wanted my relatives to know that I had fought to the end, without relaxing or giving up.”

***

The next morning I wake in the dark, drink my coffee, say the Divine Office. Sweep the floor, take out the recycling and garbage, gather the towels into a pile. Kneel by the bed and say a prayer for the next person.

Into the car go the leftover food, the freshly refrozen ice packs, the snacks for the front seat, the travel mug coffee for the 3 p.m. caffeine hit.

A U-turn, a horn beep goodbye to the ‘hood (like anyone cares), and I’m out into traffic. At the entrance ramp to the freeway I make the sign of the Cross, finger my rear view mirror crucifix, and take one last look over Tucson.

Will I be back? Do I have the strength to endure more loneliness, to stare even more deeply into the abyss, to start over one more time? Am I willing to discover new ways to allow myself to be consumed; to prepare for death?

To the casual observer, a dusty Fiat; a 68-year-old woman with wild hair and her Ray-Bans askew. But look more closely!

Her lips move in a silent plea. Her heart beats to the pulse of the universe. The morning light comes over the mountains: amethyst; blood-red.

Everything profound moves forward in disguise.

footnotes[1] Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (Boston: Beacon Press) 103, 105.

[2] In the Catholic church, a consecrated virgin is a woman who has been consecrated by the church to a life of perpetual virginity as a bride of Christ. Consecrated virgins are consecrated by the diocesan bishop according to the approved liturgical rite. Consecrated virgins spend their time in prayer, works of penance and mercy, and apostolic activity, and may live either as nuns of a monastic order or “in the world” under the authority of the local bishop.

September 27, 2022

EVERYTHING PROFOUND: PART II

For those of you who missed Part I of this 3-part essay about our existential longing for home, road trips, and food hoarding, here it is:

And here’s Part II:

Sometimes I think there are two types of people in the world: those who as infants securely attached to their mothers and those who, for whatever reason, didn’t.

Those of us who didn’t suffer from a built-in poverty of spirit. Not depression, necessarily, but poverty of spirit. Every morning of my life, my first thought has been: Will I make it through? Will this be the day I have a psychotic break? Collapse in the street? Punch someone in the face?

On my best day, with a (rare) good night’s sleep, money in the bank, and no-one (that I’m aware of, anyway) pissed at me, I still start at a deficit. I always assume that things will go wrong, that my best won’t be good enough, that I’ll give my all and “they” still won’t like me. My psychic home is the Garden of Gethsemane, where Christ sweated tears of blood the night before he died.

Also built-in for the poor in spirit is the fact that no matter how self-aware, how well-educated, observant, kind, funny, charming, and even physically attractive you may be, you will be drawn to—and yourself draw people—who are likewise poor in spirit.

For decades—most of my adult life—I tried to deny, resolve, escape that fact. I started traveling and wandering young, trying to assuage the pain. In my early 20s, for example, I hitch-hiked with a girlfriend from New Hampshire to California, stayed for a while, then took off one night without leaving a note and started hitch-hiking back, alone.

I remember with startling clarity a moment in Colorado, standing in the dark with my thumb out, when I realized that not one person in the world knew where I was. The feeling was one of indescribable peace. I didn’t want to worry the friend I’d left behind, or my parents, or anyone else: I just wanted to be alone—with God? I didn’t even believe in God in those days, that I knew of. I could think while alone? Maybe, but I don’t remember thinking any deep thoughts—I was strung out, jittery, and by that time already a full-fledged alcoholic.

Even so, way back then I saw that to travel is to enter liminal time, liminal space, a liminal dimension where I was…me but not me? An alternate me? The “real” me?

I’ve been low-key traveling ever since. Nothing fancy, nothing splashy so that anyone would want to retrace my steps. In fact, encouraging people slavishly to follow my “way,” à la Eat, Pray, Love, would nauseate me. Find your own freaking way!

Not, of course, to worry. Driving cross-country and back staying at Motel 6es, living on sardines and crackers, and going to Mass every day while suffering such severe existential torment over a romantic obsession that I broke out in boils—a little “pilgrimage” I took back in 2007—is not calculated to attract a slew of imitators.

I once gave a talk on pilgrimage to a group of well-heeled Catholic retirees, using the cross-country road trip I just described as an example. Their stares, as the tale progressed, became more and more quizzical. Finally one genteel lady raised her hand. “Why do you insist upon associating pilgrimage with pain?” she asked. “Why I went with my friends on a very nice pilgrimage to the Holy Land this past summer with Father James Martin. We stayed in lovely hotels, ate delicious meals, and sat on the banks of the Red Sea and wrote in our journals.

“Oh,” I replied. “You took the rich people’s pilgrimage!”

***

To descend into travel mode is to enter a kind of larval state—by which I don’t mean I sit in Tucson for five days half-asleep.

No indeed. I take a long walk each day. I visit San Xavier del Bac, aka “The White Dove of the Desert,” a Spanish Colonial Mission dating back to 1783. I drive to Saguaro National Park East and hike. I check out some of Tucson’s many historical neighborhoods: Presidio, Sam Hughes, Blenman-Elm. I walk to the Exo Roast Company in the Arts District; I have dinner with friends. I lead my Saturday writing workshop on Zoom, and on Monday I turn in my weekly arts and culture column to Angelus News, the archdiocesan newspaper of LA, like always.

Still, at least partially freed from my everyday life of list-making, errands, social obligations, and housekeeping, my mind also has room to wander.

The Airbnb features a charming front yard studded with agaves and succulents. In the morning I sit out there with my coffee, the air thick with birdsong, and pray the Divine Office. At dusk I’m out there again: gently rocking on the glider; pondering; admiring the rusted corrugated tin fence panels, the lizards, the resident black-and-white cat, the sunset.

St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s mother died of breast cancer when she was 4. Then, one by one, her older sisters left for cloistered convents. Finally, around the age of 12, the abandonment wound became so overwhelming that she underwent a nervous breakdown. She started having what looked like violent seizures, episodes so frightening in their intensity that her family feared she would die.

In the corner of her room stood a statue of the Blessed Virgin. She was “cured” when, one day, she saw Mary smile upon her.

In a psycho-spiritual biography called The Hidden Face, author Ida Görres describes what might have happened in that pivotal moment:

“Nevertheless, we believe that a decision must have taken place deep within her when, in the midst of her direst distress, the saving grace of the vision of Mary shone upon her. We believe that at his point Thérèse was confronted with a temptation, for all that it was hidden in the unplumbed depths of the soul. For here she was confronted with alternatives, and the second of these alternatives was the perilous one. She could accept the offered comfort, the new support and protection. That is, she could abandon her wild despair over what she had lost, could really carry out the unendurable renunciation within the core of her ego, could release the hand of [her older sister] Pauline [to whom she was codependently attached] and reach across the irrevocable gulf for the hand of the Blessed Virgin. Or—and this was the other possibility—she could cling to her despair, could hold tight to her neurosis, could maintain her protest, stubbornly persist at all costs in the sinister attempt at blackmail which this disease represented.

Such decisions take place not by deliberate processes of thought, but far below the strata of thoughts and words, by a lightning-like opening or closing of the core of being.”

Interesting word: decision. It’s derived from a root that means “to cut.”

***

I’m fascinated by the many literary figures who wrestled with Christianity: Tolstoy, Kierkegaard, Kakfa, Camus, Simone Weil, Cesare Pavese. They couldn’t bear the hypocrisy: the monstrous gap between what followers of Christ profess to believe, and how they actually live their lives. They ranted, turned their backs, came closer, pulled away, catalogued the myriad deficiencies of the Church, its members, its hierarchy, its riches.

Still, they couldn’t get rid of the ragged figure who moved from tree to tree in the back of their minds, either.

In his old age Tolstoy tried to imitate the “simple” lives of peasants, with tragicomically disastrous results.

Kierkegaard, believing himself destined for a life of loneliness, broke off an engagement to the woman he loved; then, to forestall public lionization for what he feared would be viewed as “heroism,” pretended to be a cad, thereby both breaking his fiancée’s heart and inviting public censure for a faked dereliction of duty.

Simone Weil, the French intellectual, insisted on working in a factory (though she was incompetent, loathed the work, and made no friends), possibly suffered from anorexia, and upon volunteering as a nurse in the Spanish Civil War promptly stuck her foot in a pot of boiling oil, causing burns from which she later, weakened by lack of food, fresh air, and human intimacy, died.

Weil was famous for refusing to join the Church because she preferred to be in solidarity with the souls in hell: the patron saint of Those Who Do Things the Hard Way, a club of which I count myself a charter member.

One of the saddest moments in all of literature, to my mind, is when Don Quixote “comes to his senses” near the end of the Cervantes novel. No! I wanted to shout. Keep tilting at windmills! Keep deluding yourself that Dulcinea is the most beautiful woman in the world!

The notion that “enlightenment” consists in 24/7 calm, in short, had never sat well with me. True, Christ curled up in the back of the boat during a storm and took a nap—but that wasn’t impassivity; it was trust. “I came to set the earth on fire,” he burst out on the way to Jerusalem, “and how I wish it were already kindled! (Luke 12:49). Would anyone call that “calm?”

In Orthodoxy G.K Chesterton beautifully set forth the distinction between the soporific peace sought by the world; and the “peace” of Christ:

“Even when I thought, with most other well-informed, though unscholarly, people, that Buddhism and Christianity were alike, there was one thing about them that always perplexed me; I mean the startling difference in their type of religious art…No two ideals could be more opposite than a Christian saint in a Gothic cathedral and a Buddhist saint in a Chinese temple. The opposition exists at every point; but perhaps the shortest statement of it is that the Buddhist saint always has his eyes shut, while the Christian saint always has them very wide open. The Buddhist saint has a sleek and harmonious body, but his eyes are heavy and sealed with sleep. The mediaeval saint’s body is wasted to its crazy bones, but his eyes are frightfully alive…The Buddhist is looking with a peculiar intentness inwards. The Christian is staring with a frantic intentness outwards.”

***

One night I watch a Netflix documentary about a diver in South Africa who “bonds” with a female octopus. Octopuses, as you may know, are deeply intelligent, sensitive, ingenious, playful, and can recognize individual humans. The plot is basically: the diver and the octopus come to love each other. Meanwhile, a shark cruelly bites off one of the octopus’s tentacles. She grows a new one. Then she lays a clutch of eggs, gives birth and slowly wastes away, as octopus mothers do, till the shark finishes her off.

“We must allow ourselves to be consumed,” said Mother Teresa.

Okay. But how do you get to the point where you’re willing to be consumed? How is someone drawn to Christ to begin with?

If my own experience is any indication, it helps to have a really tormented conscience; to have committed an act that’s by all rights unpardonable, unforgivable: the betrayal of a friend, the violation of a child, a lie that cost someone a job or a marriage, the taking of a life.

It helps, in other words, to have hurt another person in a way that’s so shameful you can’t just sit in a cave, and watch your thoughts float by as if on a river, and convince yourself that what you did was okay.

Another good entrée is to have suffered some truly humiliating malady: addiction, for example. You’re in thrall to the forces of darkness, and the rest of the world is just wanting you to put down the booze or needle or whatever, quit being an all-star nuisance, and shut up already.

Which, by yourself, you absolutely can’t do, no matter how smart, driven, charming, loved, or well-connected you are. Not for lack of trying—many of us die trying. Others of us are eventually graced, through absolutely no virtue of our own, with having the obsession to drink or drug removed: no questions asked, no debt incurred, welcomed back to the human table.

That happened for me in 1987: a cockeyed death and resurrection that led first to gratitude, then to the desire for a Person to thank–what other kind of God would I possibly want than a personal God?—and finally, against all odds, to Christ.

Later I learned that Flannery O’Connor had observed: “The operation of the Church is entirely set up for the sinner, which creates much misunderstanding among the smug.”

***

Everything that happens to us is extraordinarily important.

In one way, of course, who cares? The world managed fine before we came along; the world will continue a long, long time after we’re gone. But if the existential stakes are life and death, every decision we make, every act, is of extraordinary importance, of great moment.

In my own life, getting sober was a major decision: one that, like St. Thérèse’s, took place below the level of consciousness. I couldn’t have removed the obsession myself, and yet the removal didn’t take place without my consent. It marked a complete cut with my former life—my identity—as an active alcoholic.

My life since had been a series of other decisions, further cuts.

I had abortions: the wrong kind of choices, cuts, the aftereffects of which I’ll carry all my life.

A couple of years after getting sober, I got married: a cut with my identity as a single, promiscuous woman.

Soon after, my husband and I moved from the North Shore of Boston to LA: East Coast to West Coast, a cut with family, friends, autumn foliage, winter snow: the life I’d known for almost forty years.

In LA, I started working as a lawyer, using the degree I’d earned while drinking. I underwent a crisis of conscience and vocation. I made a decision to respond to the call of my heart to write, and cut ties with my career.

A year or so after that, I converted to Catholicism: a cut with the idea that my life was my own.

At 49, I got cancer: a loss of my identity as a healthy person: a cut with the delusion that I was immortal.

The next year my husband and I got divorced and I had the marriage annulled: my decision, a cut with my identity as a wife.

He went back to New Hampshire: I stayed in LA.

Freedom! I thought. Then the real fun began: I underwent an excruciating, years-long, dark night of the soul, centered upon an entirely unreciprocated romantic obsession.

Somehow during that time I continued to stay sober, help another alcoholic, function day-to-day, and remain faithful to my vocation. I wrote ten or twelve books. I planted a garden. But I was always trying to get out of my apartment and the city: monasteries, retreat houses, writers’ residencies. I kept trying to find a focus for my passion, my energy. I kept trying to form a sort of creative community, though that never really happened.

For three decades, it’s beginning to dawn on me, I’ve stayed in a city in which, from the beginning, I felt in exile.

Also for 30 years, I’ve stretched myself to the limit. I’ve never especially liked or felt safe driving: I drove all over the city and the state, constantly: first as an attorney to courthouses, depositions, and law libraries; later to the museums, theaters, concert halls, performance stages; the gardens, missions, parks, mountains and oceans about which I wrote.

Though an extreme introvert, I constantly called myself out: to the law offices where I worked at first, to the jails and prisons where I talked to my fellow alcoholics, to the Skid Row soup kitchen where I volunteered, to the snooty small press publisher in Beverly Hills, to docents, chefs, maestros, curators, lighthouse keepers, directors of domestic violence shelters, nuns who helped people die, and always, always, wherever I was in my neighborhood, city, or the state of California, to Mass.

I’ve stretched myself to the limit and made a home for myself. LA, in its unlikely way, has formed, sheltered, and sustained me. I’ve lived a good part of my life here, and I’ve reached an age where I can envision the end; more or less chart how that might play out. Not the day nor the hour but, assuming a slow decline, I have people around me who would probably help. The deterioration would probably take place in familiar surroundings, be as angst-free as possible under the circumstances.

Somehow, the prospect makes me shudder. Not the prospect of death: rather, the specter of stasis; equilibrium.

I love cities—I’ve lived in cities almost all adult life. But I was born and raised on the coast of New Hampshire, and at this point urban guerilladom has lost its luster. I don’t especially need night life, restaurants, galleries. I can find, or make, the culture I crave wherever I live. At this point all I really want—or so I tell myself—is a tree, a bird, the sun.

I’ve made this trip partly with the question in mind: Could my life bear fruit in a new, smaller city—like Tucson?

Is it time for another cut?