Julene Bair's Blog, page 8

January 19, 2015

Missouri River Aqueduct Proposal is Greed-Driven Insanity

January 2, 2015

When Words Won’t Come

Passing Through an Impasse: What I Do When the Words Won’t Come

I hate to admit this, but I’m pretty boring when it comes to kick-starting my day. I don’t have any tricks up my sleeve for that. I get up at about 6:30, do some yoga, eat some breakfast—always the same downward dog and steel-cut oats—then sit down at my computer. I try not to get hung up answering email, and just start to work where I left off the day before. I’ve always believed in the process. No tricks. Just be present and do the work. If I’m stumped by a problem passage, I often open a new file and interview myself, and that is part of the process too. The first question I ask is usually “What are you really trying to say here?” As I do my best to answer, I remind myself, “No one is going to see this. You don’t have to impress anyone.” Interviewing myself and recording the answers removes the pressure and makes me less self-conscious. I also usually ask myself what images come to mind pertaining to the work at hand, then ask why those images? Often, the answers become part of the actual text.

This is not to say I don’t get completely stymied at times. I often do, but I haven’t developed a conscious method of dealing at times like those. I’m almost afraid to talk about this, for fear I’ll come to depend on a method, which will then be part of the routine and therefore unlikely to yield answers. When I’m stuck, I unwittingly throw myself onto the breast of the universe. I get out of the chair out of pure frustration and, by way of avoidance, might choose to take a walk, which, now that I think about it, has helped many times. Being outdoors and more in my body puts me in a different mode and I sometimes find myself rushing back to the house to scribble down ideas. On the rare occasions when I go back to work in the evening after getting a little tipsy on wine, I’ve written some great stuff that I couldn’t have produced sober. (But I’ve stopped short of becoming a drunk, no matter how tempting, in order to benefit my art.) Many times, my subconscious saves me just as I’m dropping off to sleep or even as I dream. I make myself get up and write the thought or dream down. And sometimes a deadline forces me to get real in a way I’ve been avoiding. I’ve produced some of my best writing at the very last minute.

The same thing can happen during a bath. I’ve been known to take one during the middle of the afternoon. Going to water, for me, is like going to Mama, and when she hands me a line or bit of wisdom, I have to get out of the tub before I wish to in order to write it down. Going to Kansas, where I’m from, is also like going to Mama or Papa. Although my real parents are long gone, returning home awakens my deepest attachments, concerns, and interests. As I go east on I-70 and hit the grasslands around Limon, Colorado, my spirit soars. I am in my element, and I begin thinking the thoughts that matter most to me—thoughts about home.

Throughout, I’ve been talking about the drafting process. When it is time to revise or edit, one thing I have definitely noticed, and often, is that I do my best work late at night when I’m tired and therefore unimpressed by my more flowery prose, which is to say, my attempts to impress the reader without really saying anything new.

When I went to find a picture of me at my desk, my true secret popped out: It helps to have two cats for company!

November 22, 2014

Genesis of The Ogalalla Road

It all began with water. Not the water under Kansas, where I was born, but in the Sierra Nevada Mountains when I was twenty-six and recently divorced. That is when I took my first, life-changing, mind-shattering, body-awakening dive into a delectably clear mountain lake. It had been a long, hot climb. My crazy boyfriend had gone running down to the lake ahead of me, dropping his clothes as he ran. He splashed and cavorted as if having the greatest time of his life. But I was not so sure. I lay down on a boulder and trailed my fingers through the water.

“The high-altitude sun presses my back as with a dry iron, while below me, riffles slap rock. Glare refracts off the water, dappling my arm and flashing hypnotically on my retinas.” That’s how I described this pivotal moment in my new book, The Ogallala Road, A Memoir of Love and Reckoning.

Once I finally gathered the courage and dove in, I would never be the same: “It only takes a half minute or so and I’m willingly giving myself to the water and it is giving itself to me.” Soon after that first dive, the boyfriend faded into history, but the lakes came into the eternal present of my life. In all of my western travels and in all of the western places I’ve lived, I’ve been a promiscuous lake lover, dropping into each at the slightest wink of sunlight on water.

By the time I found myself back in Kansas in my thirty-fifth year, stuck due to my own poor choice in a husband, who had vanished soon after he returned me, pregnant and chagrined, to my parents’ doorstep, I had become an inveterate lake swimmer. The thought of a summer without a lake nearby bothered me so much that I attempted to swim in my father’s tail-water pit—a bulldozed hole in the ground that collected runoff from his surrounding flood-irrigated fields. This was an unsatisfactory experience, to say the least.

It became my job during those years back home to get up early each morning, plunk my baby son in his car seat, and drive one of the farm pickups out to my father’s corn and soybean fields, where I would walk along the irrigation pipes, knocking open the pipe gates and changing the sets. The water would pour out with such force that when I sliced my hand through it, I had to brace myself lest it threw my arm back and dislocated my shoulder. That’s how much water we were pouring onto our fields—one-thousand gallons per minute out of five wells twenty-four hours a day throughout much of the summer. Two-hundred million gallons per growing season. And we were just one of several thousand High Plains farmers. I knew the water wouldn’t last forever, I knew it was wrong, and I knew I was betraying my first love. The giver of life and joy. Water.

August 27, 2014

Aquifer Plays Critical Role in Pulling Farmers Through Drought

August 26, 2014

Judge Advises Texans to Learn From Their Past

June 1, 2014

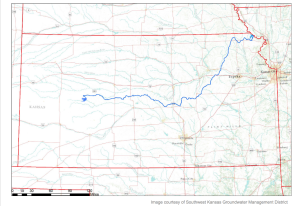

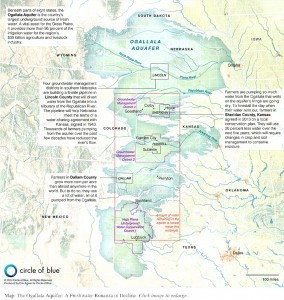

Circle of Blue Shares Important Map of the Ogallala Aquifer

No one does as good a job as reporter Brett Walton and Circle of Blue putting world water issues on the map. The latest contribution is an actual map depicting the intensifying crisis facing the Ogallala Aquifer.

April 1, 2014

From Part I, A Rare Find (Thanksgiving in Kansas)“No plat...

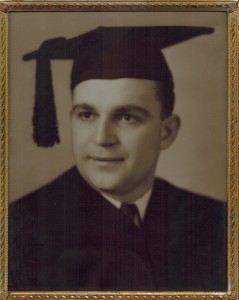

“No plate for Dad. I looked over at his college graduation picture on the buffet. His dark eyes, under heavy brows and set in a young, smooth face, stared fixedly into a future now spent. ‘Just look at that handsome rascal,’ my mother liked to say, as she gazed at the picture. ‘Is there any wonder why I married him?’”

A Familiar Clanging Noise

From The Ogallala Road, Part I, “A Rare Find”

From The Ogallala Road, Part I, “A Rare Find”“I heard a familiar clanging noise. I looked up to see a white pickup coming down the hill pulling an empty metal stock trailer behind it. Great! I thought. Now I’ve got to deal with some yokel out here in the middle of nowhere.

“I tried to warn you,” my mother said in my head, where she’d resided for as long as I could remember. “Be careful gallivantin’ out there all by yourself,” she’d cautioned me that morning as I left her house in town.”I’ve been gallivantin’ my whole life,” I’d told her. I could change a tire if I had to. I saw from the way her lips pressed together what she was thinking. She could change a tire too. That had not been what she meant.”

From The Ogallala Road, Part I, “A Rare Find” “I heard a...

From The Ogallala Road, Part I, “A Rare Find”

From The Ogallala Road, Part I, “A Rare Find”“I heard a familiar clanging noise. I looked up to see a white pickup coming down the hill pulling an empty metal stock trailer behind it. Great! I thought. Now I’ve got to deal with some yokel out here in the middle of nowhere.

“I tried to warn you,” my mother said in my head, where she’d resided for as long as I could remember. “Be careful gallivantin’ out there all by yourself,” she’d cautioned me that morning as I left her house in town.”I’ve been gallivantin’ my whole life,” I’d told her. I could change a tire if I had to. I saw from the way her lips pressed together what she was thinking. She could change a tire too. That had not been what she meant.”

From Part 1, “A Rare Find”: “I found the pond lying stil...

From Part 1, “A Rare Find”:

From Part 1, “A Rare Find”:“I found the pond lying still and innocent, a receptive, vulnerable reflection of the sky. This wasn’t rainwater. It hadn’t rained in weeks. My brother Bruce had … told me he was worried that the ground would be too parched to plant dry-land winter wheat this September. No. This pond was what the pioneers and early settlers had called ‘live water.’ It had found the surface by itself without the aid of rain, or today, a rancher’s pump. It came from the aquifer, exhaling into the bed of the Little Beaver.”