Julene Bair's Blog, page 3

January 30, 2020

Our Turn at this Earth: The Walls that Shelter Me Still

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

As a child, I lived in a big, old two-story farmhouse that my maternal grandfather had built in 1919, the year my mother was born. It never occurred to me that my family could exist anywhere else. So it came as quite a shock when I was sixteen and my parents traded that house and farm for land in another part of the county and we moved to town. Over the next two decades, the house went through different occupants, then stood vacant for many years.

As a child, I lived in a big, old two-story farmhouse that my maternal grandfather had built in 1919, the year my mother was born. It never occurred to me that my family could exist anywhere else. So it came as quite a shock when I was sixteen and my parents traded that house and farm for land in another part of the county and we moved to town. Over the next two decades, the house went through different occupants, then stood vacant for many years.

On visits back to Kansas, I used to drive out there to wander through the house’s cold and silent, high-ceilinged rooms. It felt like an empty husk. But if I thought that was strange, nothing was stranger than the inevitable day I approached along the county gravel road only to look toward the knoll where I’d grown up and discover that the house was gone. I thought I must be dreaming. How could it have simply vanished? Had I taken a wrong turn? How was that possible on a drive that had carved ruts in my memory as deep as the dry creek that ran through our north pasture? Except, wait, most of that pasture was gone too, plowed and replaced by a field of short green wheat. I drove up the two-track trail that used to be our graded road. Where the house once stood, a center pivot irrigation sprinkler circled over a field of ankle-high corn, like a wand wiping the slate of our family past clean.

I’ve paid many visits to that land since then, and whenever I do it’s uncanny how often the farmer who now owns the place spots me. He lives several miles away. Maybe he sits on top of his barn with a telescope, or maybe he hid a remote video camera in the thistles around the pit silo where he threw all of the junk from our farmstead that wouldn’t burn. All I know is there I’ll be, this woman “getting on in years,” as they say, tottering, as it were, over the furrows, trying to reconstruct in my imagination exactly where the house, two barns, chicken coop, pig sheds, granary, shop Quonset, and storage bins once stood, when along he’ll come in his big pickup. Depending on the season, we’ll stand outside or sit in his air-conditioned or well-heated cab and talk for a while.

He always tells me how he hated to tear the house down. Even though he didn’t himself grow up in this county, his wife did, and stories of my grandparents and parents still circulate among the few remaining neighbors. He doesn’t like to see history destroyed, much less be the agent of that destruction. But he couldn’t let that big flat hilltop sit idle either, not with it just crying out for a field of irrigated corn.

I tell him not to worry. I understand that farming is a business. My father would have done the same thing in his shoes.

The last few times I visited home, I haven’t felt nearly as compelled to drive out there as I used to feel. But next time I return to Kansas, I might go just to tell him why that is.

I don’t miss that house anymore. To live is to experience loss. But as people and things have dropped away from my external world, my awareness of their presence inside me has grown. My primal relationships, with my parents and other family members, formed in that farmhouse. Those people, whether living or dead, are still as much a part of me as ever. They live inside me, as does that house, with its spacious, sunlit rooms, its creaking floorboards and remembered smells. And somehow I still live inside it.

In my mind’s eye, those walls now seem as solid as ever, because my awareness of who I am has grown more solid. Among all of the losses, this is a gift that age brings.

November 15, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Ogallala Road

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/47-Ogallala-Road-Final-Mix.mp3

I’m the kind of person who can’t resist a country road. I’ll be zipping down the interstate between somewhere big and somewhere else big, and a narrow track winding between pale buffalo grass pastures will catch my eye. Next thing I know, the interstate is fading into the distance in my rear-view mirror, as I follow my nose into the next county.

I’m the kind of person who can’t resist a country road. I’ll be zipping down the interstate between somewhere big and somewhere else big, and a narrow track winding between pale buffalo grass pastures will catch my eye. Next thing I know, the interstate is fading into the distance in my rear-view mirror, as I follow my nose into the next county.

Given my penchant for such side trips, it amazed me that I’d lived in a development outside Longmont, Colorado for over six years before noticing the gravel road across from the big fancy horse ranch. I have to wonder if some mysterious force in the universe – the god of coincidences, say – had reserved that one for the right, most teachable moment.

I had recently finished an as-yet untitled book about the Ogallala aquifer, the water under most of the Great Plains, including my family’s Kansas farm. Ever since the 1980s when I had farmed with my father for awhile I’d been troubled by the threat that irrigation agriculture posed to the aquifer, which was declining rapidly. Satisfied that I’d said all I could on that topic, and eager to focus on something new, I had spent the morning before this particular drive making notes and flirting with other potential writing ideas.

So I’m on my way into town, and suddenly there’s a green road sign that, for some arcane reason, had never caught my eye before. “55th Street,” it said. Although houses were far between in that part of the county, and the so-called street was unpaved, I figured I could follow it until I came to a crossroad that would take me to town. Only after I’d gone over a couple of hills and around a few bends and I’d started to feel a little lost did that other road finally appear. I squinted as the words on its green sign came into view.

Why a road in a Front Range county over a hundred miles west of the Ogallala aquifer would be called “Ogallala Road” I did not know. The Oglala Sioux tribe, from whom the aquifer indirectly got its name, had not frequented that area much. But that sign was “a sign.” As of that moment, I knew what my book title would be. And I knew that my concern for the aquifer ran too deep to allow me to leave the Ogallala Road in my writing any time soon.

Today’s broadcast marks the conclusion of one year of weekly commentaries I’ve done for High Plains Public Radio. Many have been pleas for the preservation of the water that made my life possible, and all life possible on the High Plains for many thousands of years. I am going to take a break for a few months. In the meantime, the station will re-broadcast some of the earlier ones. I hope you’ll be listening next spring, when we’ll continue our journey together down the Ogallala Road.

November 8, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Beaver Creeks

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/46-Beaver-Creeks-Final-Mix.mp3

My father pastured his sheep on what could loosely be termed the “shores” of Little Beaver Creek, a dry watercourse that flowed only after gully washers – his term for big rainstorms. Today it amazes me that I could have grown up in that place and never wondered how the creek got its name. Nor did I wonder what happened to the water or the trees that beavers could not live without.

My father pastured his sheep on what could loosely be termed the “shores” of Little Beaver Creek, a dry watercourse that flowed only after gully washers – his term for big rainstorms. Today it amazes me that I could have grown up in that place and never wondered how the creek got its name. Nor did I wonder what happened to the water or the trees that beavers could not live without.

It wasn’t until decades later, while doing research for a book about the Ogallala aquifer, that I learned that both the Little and the Middle forks of the Beaver did flow further east in my Kansas county. Like most streams and rivers on the High Plains, they were spring fed. The water in them came to the surface where their beds cut through the Ogallala aquifer formation.

On my next visit home, excited at the prospect of seeing water in a creek I’d grown up knowing only as dry, I zigzagged along the section-line roads, stopping on bridges over the dry bed of the Little Beaver and peering upstream. When I finally spotted blue, I crawled through a barbed wire fence, then down into the bed and touched the water with bittersweet appreciation. Bittersweet, because I knew that large-scale irrigation, such as my own family now practiced, was drying up almost all surface water on the High Plains.

I saw this firsthand as, over the next decade, I paid regular visits to a Middle Beaver pond where one Jospeh Collier erected the first sod house in Sherman County. I couldn’t go home without driving out to stand in the shady glen the water created. Staring into dark, but clear, tannin-stained depths, I imagined the millions of people and animals the spring had sustained going all the way back into prehistory. But the pond and the length of the stream leading out of it dwindled each time I saw it.

Then, on a visit in 2014, I looked down from the bridge only for my eyes to fall on bare earth and weeds. I haven’t seen water in Collier’s Spring since, although I still can’t resist the compulsion to drive out there. That compulsion is what we call “hope” – unreasonable hope in this case, because hydrologists say that it will take thousands of years for the Ogallala to replenish itself and for the springs to flow again.

As to the creek’s namesake, by 1882, when Collier settled there, it is doubtful that any beavers still plied its waters. Fur trappers had nearly eradicated that animal everywhere in North America, to satisfy European demand for beaver pelts, which were felted and turned into hats.

As went the beavers in the 19th century, so go their creeks and rivers in this one. “And to what end?” we might well ask. Are corn-fattened beef and ethanol really more necessary than beaver hats? Is anything more necessary than water?

Our Turn at this Earth: Walls of Corn

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/43-Walls-of-Corn-Final-Mix.mp3

Like any farmer, my father loved driving along a wall of green corn and computing the many bushels it would yield and the money these would put into his bank account. He irrigated his corn out of the Ogallala aquifer, and always believed that the government would shut him down before he ran out of water. Meanwhile, the government was actually encouraging water use by subsidizing his corn crop through the Farm Program. In 2007, ten years after my father’s death, the federal government further intensified the aquifer’s decline by passing the Renewable Fuel Standard. The resulting demand for corn, as feedstock for ethanol, led to a drastic expansion in corn acres.

Like any farmer, my father loved driving along a wall of green corn and computing the many bushels it would yield and the money these would put into his bank account. He irrigated his corn out of the Ogallala aquifer, and always believed that the government would shut him down before he ran out of water. Meanwhile, the government was actually encouraging water use by subsidizing his corn crop through the Farm Program. In 2007, ten years after my father’s death, the federal government further intensified the aquifer’s decline by passing the Renewable Fuel Standard. The resulting demand for corn, as feedstock for ethanol, led to a drastic expansion in corn acres.

Despite many impressive new technologies, such as soil moisture sensors and variable rate sprinkler systems that can apply water only as needed, farmers are on a collision course with a fundamental disparity: Irrigated corn requires that they pump over a foot of water out of an aquifer that receives less than an inch of rain and snowmelt each year. Yet, to date, few have questioned the wisdom of growing a crop that exceeds the aquifer’s recharge rate many times over. Nor do many question the role that federal Farm Program and ethanol policies play in the aquifer’s decline.

With prices now low, and walls of dollars no longer piling up behind walls of corn, this might be a good time to open that discussion. Why does the Farm Program offer High Plains farmers revenue protection insurance on yields that can only be achieved by draining the nation’s largest aquifer? Is the Renewable Fuel Standard, which requires that ethanol be mixed with the nation’s fuel supply, ultimately good for farmers’ bottom lines? It spurred a boom that tripled corn prices and land values, but also caused a glut of corn on the market that drove corn prices back down. Land prices are sure to follow. How many farmers find themselves underwater in debt while having used up most of the water belowground?

Shouldn’t federal dollars go toward preserving national resources and promoting longevity in agriculture rather than policies that deplete reserves of soil and water and fuel a boom-and-bust ag economy? Instead of paying farmers to grow a crop that depletes the water that future generations will need, the government could pay farmers to regenerate their soil, or to return more land to grass, or to finish cattle on grass, or to water less, or to grow more drought-tolerant crops.

As long as those federal dollars continue to flow, I would think that farmers would actually prefer they be spent on keeping their soil and the water beneath it in as good a shape as possible. U. S. representatives and senators must run for election in farm country. It is up to farmers and the citizens of communities that depend on the Ogallala aquifer to tell them what they value most. Which will it be, water or corn?

November 1, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Carbon Cycle

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/45-Carbon-Cycle-Final-Mix.mp3

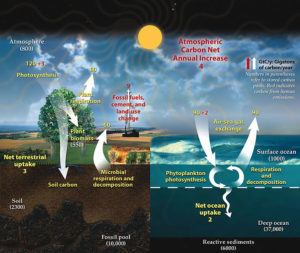

Stories about disruptions in the carbon cycle abound in the news these days. But recently, it occurred to me that I didn’t really know what the carbon cycle was. A few Google searches later, and I will never again see my fall garden in quite the same way. It has always seemed a miracle to me that a tiny seed can sprout into a squash vine that takes over my backyard. Well, now I know that during photosynthesis, plants use the sun’s energy to rearrange the carbon from carbon dioxide, and the hydrogen and oxygen in water, into glucose, which they use to grow. Carbon, I read over and over, is the “building block of life.” All plant and animal tissue is carbon based.

Stories about disruptions in the carbon cycle abound in the news these days. But recently, it occurred to me that I didn’t really know what the carbon cycle was. A few Google searches later, and I will never again see my fall garden in quite the same way. It has always seemed a miracle to me that a tiny seed can sprout into a squash vine that takes over my backyard. Well, now I know that during photosynthesis, plants use the sun’s energy to rearrange the carbon from carbon dioxide, and the hydrogen and oxygen in water, into glucose, which they use to grow. Carbon, I read over and over, is the “building block of life.” All plant and animal tissue is carbon based.

While growing, plants also put carbon into the soil, where multitudes of tiny other life forms use it to build their tissue. If I leave dead plant matter on the surface of my garden, bacteria will decompose it. Those bacteria will release some carbon, in the form of carbon dioxide, back into the air, but they will also carry some of it downward into the soil. When I eat the vegetables I grow, my body, in turn, uses their carbon-based tissues to build its own tissues and also exhales CO2, doing its part in the carbon cycle.

Over millions of years, decayed marine plant and animal life formed carbon-rich natural gas and oil and coal. When we burn these fossil fuels, we suddenly release carbon that has been sequestered for millions of years belowground. Since 1750, when the Industrial Revolution began, the amount of CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere has increased by over 30 percent. It has been at least 800,000 years since that much CO2 has been present in the air above our planet. Less of the sun’s heat can escape the atmosphere than in the past, because it is trapped by those increasing levels of CO2. That is why, over the 136 years that records have been kept, average world temperatures have been climbing. Seventeen of the last 18 years were the hottest.

That is bad news for farmers, because excessive heat interferes with crop growth. But with every challenge comes new opportunities. Enter carbon farming, one of the most promising ways to combat climate change. By growing cover crops and refraining from tillage, farmers can cool their soil, expand its water-holding capacity, and improve its fertility while also sequestering carbon in the ground. Some governments around the world already pay for that service by issuing carbon credits to farmers, who can then sell them to industries that release more than their share of carbon into the atmosphere. It would be good for farmers, not to mention the rest of humanity, if our government would do that too.

October 18, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Animal Stories

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/44-Animal-Stories-Final-Mix.mp3

My mother used to tell a story about a dog that our family had before I was born. She swore he could read her mind. “’Elmer, ‘ I said to him one time, “why don’t you get me that chicken?’ I didn’t even point. But danged if he didn’t go over and grab me the chicken I’d been thinking about.”

Mom also liked to recall the time she placed duck eggs into the nest of a mother hen. “Well,” she said, “when they hatched and got a little older, they slipped through the fence and went swimming in the pond. Oh did that hen have a conniption.” Then there was a giant “pet” toad, who used to sit on the porch step summer evenings with her and her family, to gorge on the June bugs that flocked to the light coming through the screen door.

I grew up on that same farm, surrounded by barks, meows, oinks, clucks, neighs, moos, and, since my father had gone big time into the sheep business, lots and lots of baas. Each of those sheep had its own voice – some high, some low, some scratchy, some clear. Each was a unique individual, like all of the animals on the farm.

Take Cat-tastrophe, for instance, a yellow tiger cat who was always getting into fixes. Once he fell into a ten-foot-tall concrete storage tank in the well house. He yowled for days until he finally figured out that he could climb out on the strips of old sheets we’d tied together for him. Or take Flopsy, our corpulent black terrier mix named for her long floppy ears. After losing a litter of pups, she adopted and nursed a kitten we called Freak because its mother had rejected it. Then we had Joe the Crow, who would sit on the clothesline and swoop down to scare off any cats who tried to eat from the bowl he considered his.

By the time I started grade school, I’d already had an education in the ways of many wild members of the animal kingdom – not only from Joe the Crow, but from the hog snakes, garter snakes, doves, pigeons, burrowing owls, raccoons, toads, lizards, salamanders, cottontails, jack rabbits, and box turtles that we’d captured and tamed. Such intimacy with animals was a large part of what it meant, in my childhood and my mother’s, to grow up on a farm.

Then, when I was sixteen, my parents traded that farm for land near another farmstead they owned and built a new house in town. They either sold or moved all of the remaining animals to the other farm. Mom didn’t want to deal with cat hair in the flawless new house, so not even our house cat moved with us. Only years later would I look back and realize that, in giving up a life surrounded by so many animals, we’d also given up our way of life.

October 1, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Elephant, or Cash Cow?

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on HIgh Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/42-Elephant-or-Cash-Cow-Final-Mix.mp3

A few years ago I attended a meeting in my hometown, Goodland, Kansas. It had been called by the Vision Team, appointees of then Governor Sam Brownback, who had taken a noteworthy interest in conserving the Ogallala Aquifer. We hundred or more attendees were divided into groups of around eight each and asked to address a series of questions. For instance, what role might technology play in conserving the aquifer? And how could education about the aquifer be improved? But the question that stands out in my memory asked, simply, “How long should the water last?”

A few years ago I attended a meeting in my hometown, Goodland, Kansas. It had been called by the Vision Team, appointees of then Governor Sam Brownback, who had taken a noteworthy interest in conserving the Ogallala Aquifer. We hundred or more attendees were divided into groups of around eight each and asked to address a series of questions. For instance, what role might technology play in conserving the aquifer? And how could education about the aquifer be improved? But the question that stands out in my memory asked, simply, “How long should the water last?”

I was struck by the earnest and heartfelt responses of the farmers at my table. “The water should last for generations,” one man said. “Forever,” said another. These wishful aspirations were met with forlorn nods. No one said, as many farmers had in news stories I’d read over the years, that the water was theirs to use as they pleased and leaving it in the ground wouldn’t do anyone any good. I guess that enough water had passed under the bridge, or through irrigation pipes, for them to realize that a crisis was truly upon them. Several worried that, unless they took serious measures now, the water would soon be gone, and their children and grandchildren wouldn’t be able to profit from the land as they had.

Although new seed varieties and technologies did make it possible to use less water, the farmers readily admitted that these would only slow the aquifer’s decline. I kept waiting for someone to mention the elephant in the room, but since no one did, I guessed it was up to me. Heart thumping, I said that the federal government was driving the aquifer’s depletion with the ethanol mandate, and by subsidizing crop insurance for corn, the crop grown most widely on irrigated acres.“Don’t you think that the mandate should be ended,” I asked, “and the government should pay you instead to retire your water rights or, at the very least, grow more drought-tolerant crops?”

“Corn is very water-efficient,” one young farmer proclaimed. The nods around the table this time were insistent and affirming. But I had filed my father’s irrigation reports with the Kansas Water Office for over twenty years, and I had done the math. We had used, on average, 1900 gallons of water per bushel of corn, which amounted to more than twice the water that fell from the sky in a normal growing season. In down markets, government subsidies had been the only reason we had made money on the crop.

But not one farmer at that table was willing to entertain changes in government corn policy. Each of them did want the water to last forever. They really did, but they didn’t want to give up their most profitable crop even if that was the only way to save it. Who could blame them? What else can be expected when the elephant in a room is also a cash cow?

September 27, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Great Plains Are Not the Midwest

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on HIgh Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/41-Great-Plains-Not-Midwest-Final-Mix.mp3

“He thought he knew what he was going to see, but now that his horse stood on the summit, he couldn’t believe. He couldn’t believe that flat could be so flat or that distance ran so far or that the sky lifted so dizzy-deep or that the world stood so empty. … He thought he never had seen the world before. He never had known distance until now. He had lived shut off by trees and hills and had thought the world was a doll’s world and distance just three hollers away and the sky no higher than a rifle shot.”

“He thought he knew what he was going to see, but now that his horse stood on the summit, he couldn’t believe. He couldn’t believe that flat could be so flat or that distance ran so far or that the sky lifted so dizzy-deep or that the world stood so empty. … He thought he never had seen the world before. He never had known distance until now. He had lived shut off by trees and hills and had thought the world was a doll’s world and distance just three hollers away and the sky no higher than a rifle shot.”

That passage from A. B. Guthrie’s novel, The Way West, describes a pioneer’s first view of the Great Plains when he reaches, what is today, central Nebraska on the Oregon Trail. I first read that book 30 years ago, as a returning student at the University of Iowa. The description stuck with me because whenever I drove the 800 miles back to my family’s farm in the Colorado-Kansas border region, I would notice the sky lifting and the earth widening about the time I reached central Kansas. With each breath of lighter, dryer air, I drew the sunny expansiveness of the Plains into my lungs and knew I was home.

On the map in my sixth grade geography book, the Great Plains region began in Texas, reached all the way to the Canadian border, and was signified by a few stalks of wheat. The Midwest, to our east, had a shock of corn, a crop that didn’t grow too well on the Plains because we were in the rain shadow of the Rocky Mountains.

Today it jars me when someone from a Plains state, especially from the dryer western half of one, refers to him or herself as a Midwesterner. When I think “Midwest,” I envision tree-lined rivers winding through bucolic hills covered in emerald green fields of corn or grass. I see church steeples poking up between the hills, which nestle hamlets of stately white houses.

Think “Plains,” on the other hand, and I see flat, treeless expanses interrupted only rarely by a modest creek or river. Tall white grain elevators overlook towns where each straight, wide, sunlit street opens onto a stretch of lime-green buffalo grass or yellow wheat. That’s in my mind. I know that today the streets often end in walls of corn. That crop has marched down off of the Iowa hills onto the Plains – an invasion enabled by government incentives combined with plainspeople’s willingness to use up their only water source, the Ogallala Aquifer, to grow a crop ill-suited for their climate.

Today we hear a lot about climate change denial. But how are we to notice and take responsibility for changes in our climate if we have not, as yet, even learned to accept and work compatibly with the climate we already have?

September 20, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Soil Detective – Regenerative Ag on the High Plains

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on HIgh Plains Public Radio.

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/40-Soil-Detective-Final-Mix.mp3

Michael Thompson – Reprinted with permission of John Deere’s The Furrow magazine. Copyright (c) 2018 Deere & Company. All worldwide rights reserved.

Over the past few weeks I’ve been talking a lot about regenerative farming techniques. “But could they work where I’m from?” I kept wondering. In order to find out, I spoke with Michael Thompson, a sixth generation farmer from Norton County, Kansas, who grew up thinking, like I did, that wheat ground had to be fallowed every other year and kept bare to accumulate moisture for the next crop.

To consider planting cover crops on fallow ground in our part of the country would have been greeted as heresy. But Michael explained that, after close to a century of tillage, his family’s soil had become a “degraded resource.” With only one percent organic matter left, it had next to no water-holding capacity. He knew that unless he became what he called a “soil detective” and figured out how to heal his soil, the farm would not be able to support him and his family in addition to his parents.

He began by adopting no-till practices, which meant leaving crop residue on the fields, planting back into it, and killing weeds with herbicides. But this approach by itself didn’t improve soil health as much as Michael hoped it would. Nor did the bottom line on the Thompsons’ 4,000 acres of crop and rangeland improve much.

So he tried incorporating cover crop mixes with no-till, which proved far more successful. Employing a rotational grazing system, the Thompsons now run cattle on the cover crops they plant between cash harvests. Because covers keep the ground cooler and leave much more residue than no-till did, organic matter has more than doubled, and even tripled in some fields, with corresponding increases in the soil’s water-holding capacity. Deep-rooted covers such as daikon radish have broken up the pan layers in the soil, allowing cash-crop roots to reach further down into the soil profile. Because weeds can’t compete with covers, fewer herbicides are needed. Consequently, fungi can thrive, supplying water and nutrients to plants through finer spaces than roots can penetrate.

The soil detective can explain in detail how cover crops recycle nutrients too. But suffice it to say that Michael saves many thousands on fertilizers and herbicides, and has made many thousands on the additional cattle the system enables, and on better yields. It is hard to imagine any High Plains farmer not getting excited about the improvements to Michael’s bottom line, or on hearing about the 58 bushel dry-land corn crop he grew on just seven inches of rain during the 2012 drought.

But the real payoff, Michael says, will come years down the pike, when his children inherit the farm. As he told one of his other interviewers, “We’re trying to leave the land in at least as good a shape if not better shape than what we found it in.” Don’t all farmers want to do that? The groundwork that Michael and other regenerative pioneers have laid puts that goal within everyone’s reach.

September 13, 2018

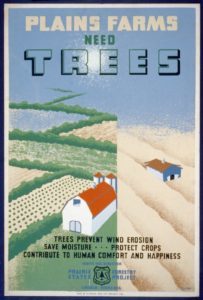

Our Turn at this Earth: The Farm Forest that Never Was

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on HIgh Plains Public Radio

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/39-The-Family-Forest-Final-Mix.mp3

When it came time to plant a new windbreak on my family’s farm back in the 1980s, my father wanted just junipers or elms, while I wanted both of those, plus lilacs, Russian olives and plums, not in rows, but all mixed together randomly, like in a real forest. We fought over those trees the way close family members will do, as if our separate wishes were a threat to our mutual identity. He must have felt as if I were rejecting his very way of life and being, while I yearned for him to accept and share my taste for wildness

When it came time to plant a new windbreak on my family’s farm back in the 1980s, my father wanted just junipers or elms, while I wanted both of those, plus lilacs, Russian olives and plums, not in rows, but all mixed together randomly, like in a real forest. We fought over those trees the way close family members will do, as if our separate wishes were a threat to our mutual identity. He must have felt as if I were rejecting his very way of life and being, while I yearned for him to accept and share my taste for wildness

Recently, on a backpacking trip to the Sierra Nevada mountains, I kept noticing the two features I’d argued for in that windbreak all those years ago – variety and randomness. The six or seven tree species, mostly pines and firs, that towered above me hadn’t been planted according to any plan, but had sprung up wherever fate afforded them an opportunity. In some places solitary junipers had found purchase in fissures on otherwise smooth granite, while elsewhere the trail took me through groves as enchanting, dark and green as one of the mythical forests in Lord of the Rings. Because no gardener paid visits to cull or prune, some of the giants had fallen and now lay on their sides, covered in moss or drilled full of woodpecker holes, their gnarly roots as beautiful as any sculpture.

To stand in those groves among the living and dead, with a lake glimmering between the branches, hawks soaring overhead, and a beak knocking resonantly now and then in the distance, was to stand in the midst of the whole grand, operatic creation. The little forest I’d wanted to plant on our farm wouldn’t have comprised one bar in that opera, but I had craved that semblance of the wild—the randomness and variety—just the same.

As it turned out, I did get the variety. My father even consented to planting four lilacs between every pair of Russian olives in the first row. But I didn’t get the randomness. Our three-hundred trees stood at attention row by row, like soldiers. My dad liked to point out that if we’d planted them willy-nilly, as I’d wanted to, all we would have wound up with was a field of random weeds. We wouldn’t have been able to machine cultivate, or water automatically. Drip irrigation hose kinks easily. It needs to be laid straight, not in curlicues.

I wasn’t above admitting that I was wrong but there were things about which I was right too, things that my father never saw. He had a farmer’s mentality, meaning he approached nature strictly with the purpose of taming it to reap practical benefits from it. I would never have the satisfaction of sharing my love for wildness with him. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons I’m sharing it with you.