Julene Bair's Blog, page 10

December 4, 2013

J.Bair

I went to Kansas in October to film a book trailer for The Ogallala Road. While there, I made some exciting discoveries and some sad ones. It was exciting to see the Republican River running higher than I’d ever witnessed.Could this be due to the immense rains received there and to the west, in Colorado, in September? Or is it because the Republican River Compact battle between Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado resulted in Colorado shutting off water to Bonny Dam, a reservoir on the Colorado side of the border? (Here’s a handy thumbnail history of this battle, which proves the old western saying that “whiskey is for drinkin’ and water for fightin’.”) Whichever it was, I delighted in the water, as you can see.

October Swim

When water gifts itself in this way, it is something to be thankful for and treasure. How could we forget this? But that’s exactly what has happened. People in Kansas and throughout the High Plains have become accustomed to thinking of this once beautiful land as mere farm ground and nature as servant to their monetary needs. This utilitarian view has caused them to pump the water from under that ground and forget the thrill of seeing it come to the surface “of its own accord,” a phrase from a definition I once read of a spring.

There is nothing more personal than a dive into a lake or river. It is like entering a lover’s full embrace, and in this case it was also very bracing. Nature has always been very personal for me—ever since I was a tiny child enchanted by wide skies and broad prairies.

How do we restore natural beauty to the prominent place it merits in the hearts of the land’s inhabitants? My answer was to write a book spilling my heart out—a book that made little distinction between what was “out there” and “in here,” because the two landscapes, outer and inner, are intertwined for those of us who were thoroughly imprinted by the earth’s beauty as children. It has been my good fortune to have those child memories amplified by my rambles through western deserts and mountains, and, yes, by a thousand dives into the waters nature gifts us.

For this reason, it was especially sad, in October, to visit Big Springs, the site on Middle Beaver Creek where Sherman County’s first settlers lived and where the Cheyenne Indians used to hold sun dances. As I say in the book trailer I’ve been working on, there would be three or four thousand Indians at these dances, and horses in at least four or five times that number. Imagine how much Ogallala water must have come to the surface “of its own accord” to make those gatherings possible. I visited Big Springs about ten years ago, with Ward, the man I met when I first began researching my book and who became a central figure in the story. At that time, the spring was already much diminished, but it looked to be at least as deep as my chest. (This was one of the few times that I didn’t go into the water.) This is what Big Springs looked like in October:

What Was Once Big Springs

We can blame this travesty on both the severe drought of 2011-2012 and on irrigation, which draws the water table down so far that the water no longer seeps into the creek beds. Those are the immediate causes. But more than this, we must look to our own failure to understand who we are as a people and our forgetfulness of what gives us not only life, but joy. Could we change this pattern? Those of us who recognize it have no choice but to try.

November 30, 2013

Nature is Personal

I went to Kansas in October to film a book trailer for The Ogallala Road. While there, I made some exciting discoveries and some sad ones. It was exciting to see the Republican River running higher than I’d ever witnessed.Could this be due to the immense rains received there and to the west, in Colorado, in September? Or is it because the Republican River Compact battle between Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado resulted in Colorado shutting off water to Bonny Dam, a reservoir on the Colorado side of the border? (Here’s a handy thumbnail history of this battle, which proves the old western saying that “whiskey is for drinkin’ and water for fightin’.”) Whichever it was, I delighted in the water, as you can see.

October Swim

When water gifts itself in this way, it is something to be thankful for and treasure. How could we forget this? But that’s exactly what has happened. People in Kansas and throughout the High Plains have become accustomed to thinking of this once beautiful land as mere farm ground and nature as servant to their monetary needs. This utilitarian view has caused them to pump the water from under that ground and forget the thrill of seeing it come to the surface “of its own accord,” a phrase from a definition I once read of a spring.

There is nothing more personal than a dive into a lake or river. It is like entering a lover’s full embrace, and in this case it was also very bracing. Nature has always been a very personal for me—ever since I was a tiny child enchanted by wide skies and broad prairies.

How do we restore natural beauty to the prominent place it merits in the hearts of the land’s inhabitants? My answer was to write a book spilling my heart out—a book that made little distinction between what was “out there” and “in here,” because the two landscapes, outer and inner, are intertwined for those of us who were thoroughly imprinted by the earth’s beauty as children. It has been my good fortune to have those child memories amplified by my rambles through western deserts and mountains, and, yes, by a thousand dives into the waters nature gifts us.

For this reason, it was especially sad, in October, to visit Big Springs, the site on Middle Beaver Creek where Sherman County’s first settlers lived and where the Cheyenne Indians used to hold sun dances. As I say in the book trailer I’ve been working on, there would be three or four thousand Indians at these dances, and horses in at least four or five times that number. Imagine how much Ogallala water must have come to the surface “of its own accord” to make those gatherings possible. I visited Big Springs about ten years ago, with Ward, the man I meant when I first began researching my book and who became a central figure in the story. At that time, the spring was already much diminished, but it looked to be at least as deep as my chest. (This was one of the few times that I didn’t go into the water.) This is what Big Springs looked like in October:

What Was Once Big Springs

We can blame this travesty on both the severe drought of 2011-2012 and on irrigation, which draws the water table down so far that the water no longer seeps into the creek beds. Those are the immediate causes. But more than this, we must look to our own failure to understand who we are as a people and our forgetfulness of what gives us not only life, but joy. Could we change this pattern? Those of us who recognize it have no choice but to try.

October 21, 2013

Genesis of The Ogalalla Road

It all began with water. Not the water under Kansas, where I was born, but in the Sierra Nevada Mountains when I was twenty-six and recently divorced. That is when I took my first, life-changing, mind-shattering, body-awakening dive into a delectably clear mountain lake. It had been a long, hot climb. My crazy boyfriend had gone running down to the lake ahead of me, dropping his clothes as he ran. He splashed and cavorted as if having the greatest time of his life. But I was not so sure. I lay down on a boulder and trailed my fingers through the water.

“The high-altitude sun presses my back as with a dry iron, while below me, riffles slap rock. Glare refracts off the water, dappling my arm and flashing hypnotically on my retinas.” That’s how I described this pivotal moment in my new book, The Ogallala Road, A Memoir of Love and Reckoning.

Once I finally gathered the courage and dove in, I would never be the same: “It only takes a half minute or so and I’m willingly giving myself to the water and it is giving itself to me.” Soon after that first dive, the boyfriend faded into history, but the lakes came into the eternal present of my life. In all of my western travels and in all of the western places I’ve lived, I’ve been a promiscuous lake lover, dropping into each at the slightest wink of sunlight on water.

By the time I found myself back in Kansas in my thirty-fifth year, stuck due to my own poor choice in a husband, who had vanished soon after he returned me, pregnant and chagrined, to my parents’ doorstep, I had become an inveterate lake swimmer. The thought of a summer without a lake nearby bothered me so much that I attempted to swim in my father’s tail-water pit—a bulldozed hole in the ground that collected runoff from his surrounding flood-irrigated fields. This was an unsatisfactory experience, to say the least.

It became my job during those years back home to get up early each morning, plunk my baby son in his car seat, and drive one of the farm pickups out to my father’s corn and soybean fields, where I would walk along the irrigation pipes, knocking open the pipe gates and changing the sets. The water would pour out with such force that when I sliced my hand through it, I had to brace myself lest it threw my arm back and dislocated my shoulder. That’s how much water we were pouring onto our fields—one-thousand gallons per minute out of five wells twenty-four hours a day throughout much of the summer. Two-hundred million gallons per growing season. And we were just one of several thousand High Plains farmers. I knew the water wouldn’t last forever, I knew it was wrong, and I knew I was betraying my first love. The giver of life and joy. Water.

Is Cutback of Ogallala Aquifer Use in Kansas Newsworthy?

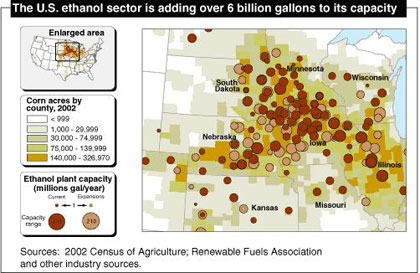

What is stressing the Ogallala Aquifer? Look no farther than U.S. Ethanol Expansion.

In short, yes. I think the fact that a few western Kansas farmers have agreed to voluntarily cut back on the amount of water they are taking from the Ogallala Aquifer is newsworthy. So, apparently, do a lot of major news outlets, the most recent being NPR. In order to stretch the water out a little bit longer, the farmers in one “intensive groundwater use control area” will reduce withdrawals by twenty percent over the next five years. This is not going to save the aquifer–not by a long shot, but in a society that often encourages individual profit at the expense of the common good, the willingness to exert a little self-control is indeed newsworthy.October 17, 2013

Rick Bass and Writing About Places Where “Possibility Still Exists”

Rick Bass’s characters often find themselves…. I was going to finish that thought, but then realized I already had. They find themselves, in a place, with a problem. They are self-aware and honest about their predicaments. But it’s hard to generalize about Bass’s characters, because, in his story “The Prisoners,” for instance, he gives us those three “prisoners” going down the highway oblivious to their own hurts and needs. So much is wrong with their lives that catching a few fish cannot fix. That’s true for most of us. Yet wilderness and big land can help a lot. It is the way he brings all that is above, below, and on the earth to magical, mysterious life that keeps me turning the pages of his books well into the night.

Rick Bass’s characters often find themselves…. I was going to finish that thought, but then realized I already had. They find themselves, in a place, with a problem. They are self-aware and honest about their predicaments. But it’s hard to generalize about Bass’s characters, because, in his story “The Prisoners,” for instance, he gives us those three “prisoners” going down the highway oblivious to their own hurts and needs. So much is wrong with their lives that catching a few fish cannot fix. That’s true for most of us. Yet wilderness and big land can help a lot. It is the way he brings all that is above, below, and on the earth to magical, mysterious life that keeps me turning the pages of his books well into the night.

October 7, 2013

Brenda Peterson’s Build Me an Ark: A Life with Animals

Author Brenda Peterson has led a charmed life among animals. But her book Build Me an Ark: A Life with Animals, makes clear that her life is charmed only because she has always gone out of her way to meet the animals more than halfway. The experiences she comes back to report–among dolphins, whales, dogs, cats, bears–startled and often moved me to tears. Who knew that a whale in deep mourning over the loss of her calf would take a woman’s arm in her mouth and gently “sound” the woman? Who knew that dolphins are so emotionally telepathic that they will hone in on a woman in constant pain or choose to dance her through the water in the grip of their fins and their deep wells of compassion? I put this book down thinking, I must pay more attention. I must be present and notice the incredible intelligence that shares this planet with me and open my heart wide to its messages and its plight, which is my own. (Who knew that a dolphin’s or whale’s milk is often so laden with heavy metals and other toxins that it can and often does kill nursing young–or that the same is true of Inuit women who depend on a diet of whale blubber?) Peterson demonstrates again and again that we share a soul with animals and that their future and ours are inextricably linked.

Author Brenda Peterson has led a charmed life among animals. But her book Build Me an Ark: A Life with Animals, makes clear that her life is charmed only because she has always gone out of her way to meet the animals more than halfway. The experiences she comes back to report–among dolphins, whales, dogs, cats, bears–startled and often moved me to tears. Who knew that a whale in deep mourning over the loss of her calf would take a woman’s arm in her mouth and gently “sound” the woman? Who knew that dolphins are so emotionally telepathic that they will hone in on a woman in constant pain or choose to dance her through the water in the grip of their fins and their deep wells of compassion? I put this book down thinking, I must pay more attention. I must be present and notice the incredible intelligence that shares this planet with me and open my heart wide to its messages and its plight, which is my own. (Who knew that a dolphin’s or whale’s milk is often so laden with heavy metals and other toxins that it can and often does kill nursing young–or that the same is true of Inuit women who depend on a diet of whale blubber?) Peterson demonstrates again and again that we share a soul with animals and that their future and ours are inextricably linked.

October 3, 2013

Kristen Iverson’s Full Body Burden

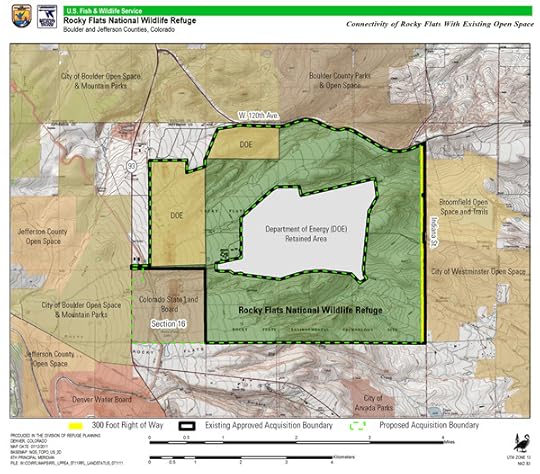

Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge

For an amazingly-well researched and galvanizing example of the environmental memoir genre look no farther than Kristen Iverson‘s Full Body Burden: Growing up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats. I’ve lived in Colorado for about eight years, but even though I’d heard people question the sanity of turning the former nuclear weapons facility at Rocky Flats into a wildlife refuge, I had no idea how extensive the radioactive pollution was.

Iverson grew up in Arvada just east of the plant in an era when few people questioned big business or the government’s practices. They rested assured that “they would tell us” if it wasn’t safe. Not only did “they” not tell anyone then, the truth about the nuclear waste still in the soil and water at and around Rocky Flats continues to be suppressed. I will no longer breathe nearly so freely as I once did when the wind comes out of the south.

Iverson has won many awards for her book, most recently, and well-deserved, the Colorado Book Award.