Julene Bair's Blog, page 5

June 28, 2018

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 p...

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/29-Dream-Women-Final-Mix.mp3

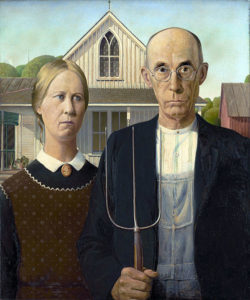

“American Gothic,” Grant Wood

In the dream, a little girl stands beside a row of women. The women are dressed demurely in dark dresses such as the ones my mother’s mother wore—navy blue with tiny polka dots or dark green bordering on black. They sit erect in straight-backed chairs, their hands folded in their laps. The girl moves from one woman to the next, asking, “Do you have any magic?” Each in turn smiles indulgently at the girl. “Oh my! Why no, dear.”

The little girl, of course, was me. And those women, in their dourness and denial? They were the distilled, reticent essence of the women I grew up around. My mother and her friends didn’t wear dark dresses. They wore bright ones, and laughed often. I picture them at ladies’ club meetings, holding fancy saucers with cup rings on them to keep their delicate cups from splashing coffee onto the hostess’s homemade cookies. But there were certain things they never talked about, certain things that they would go to their death beds never having shared.

They were stoic. That word, often applied to pioneers and their descendants, brings “American Gothic,” the famous Grant Wood painting, to mind. An elderly farmer stands as erect as the pitchfork he holds at his side, his wife beside him. Studying an image of that painting just now, I note that the farmer sternly faces forward, looking the viewer in the eye. But his wife, although her expression is also severe, looks slightly off to the side. She is not connected to the viewer, and I would venture, she is not that in touch with herself. She seems, in fact, to be somewhere else entirely.

My mother was not severe, but she was emotionally inaccessible. I knew not to ask her personal questions. She had grown up in a family who didn’t share their feelings. Therefore I was growing up in such a family.

I never realized this was unusual until my mid-thirties when I went back to college and joined a women’s writing group. No fancy cups and saucers there. We met at a Mexican restaurant. Over enchiladas and margaritas, we critiqued one another’s short stories, and discussed… what else but the intimate details of our private lives? That’s how women are. We can meet at a party and be sharing our personal stories within minutes. It is how we connect, how we grow, and how we learn.

What caused the farm women of my childhood to withhold so much of themselves? Lacking sounding boards for their emotions on remote homesteads, had they forgotten they had emotions?

I don’t know. All I do know, thanks to those women I met when I returned to college, is what I had been missing until then. The magic in that dream, the magic that each woman in turn claimed not to have? It was not the power to feel. We all feel. It was the power to know their feelings.

June 21, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Finding the Right Words

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR,

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/28-Finding-The-Words-Final-Mix.mp3

Creative Commons CCO

It’s happened many times. There I’ll be driving innocently down a western Kansas road, and a stretch of buffalo grass will reach out and grab me, almost pulling me into the ditch. Often, I’ve had to stop the car and get out, as I did one February afternoon a few years ago. Here’s the description I wrote later that evening for my book, The Ogallala Road: “…[P]redominantly grayish-brown with only a hint of green this late in the winter, the grass also had patches of salmon. No single or solid color anywhere—everything complex, everything variegated, like the human eye and human consciousness. That is why coming upon a patch of wild prairie affirms me so much. Wild life recognizes wild life. All life is wild at center. We need the natural world to know ourselves.”

The composer Ludwig van Beethoven used the word “resonance” to describe our relationship to nature. And resonance is exactly what I felt as I stood on that roadside in mid-winter, breathing in the smells of dampening earth and grass, unable to pull myself away despite the sleet hitting my face. Something deep within me resonated with my surroundings.

It wasn’t merely a matter of liking, or even loving, what I saw on that February afternoon. Standing in the presence of a large expanse of healthy, unfarmed grass any time of year soothes me. It restores calm, and gives me the impression that things are right with the world. Although things may be far from right elsewhere, they are right in that place. Put simply, if nature is okay, so am I, because I am part of nature.

In her book The Nature Fix, science writer Florence Williams cited an MRI study in which “parts of the brain associated with pleasure, empathy, and unconstrained thinking” received more blood flow when subjects viewed pictures of nature. “Empathy,” I thought, “yes. Pleasure, yes.” But it was the word “unconstrained” that leapt out at me. On unfarmed prairie, I can feel my mind opening the way my lungs open when breathing fresh clean air. We use the word “freedom” in association with open landscapes because of the freedom we feel when we’re in them. We identify not only with the openness but with the vitality of the grand, living world.

The biologist E. O. Wilson’s word for this was “biophilia”—‘bio’ meaning life, ‘philia’ meaning love. He defined it as the “innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms.” We are biophiliacs one and all.

But not all people are as obsessed as I am with seeing what is left of the natural world on the plains preserved. That is why I search for the right words to share my passionate belief. The wildness outside us speaks to the wildness inside us. Wildness resonates within us. It soothes.

June 14, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: “The Nature Fix”

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/27-Nature-Fix-Final-Mix.mp3

Back in my late twenties, after my marriage had ended, I just couldn’t stand being in the city. I fled to the Mojave Desert every chance I got, because in the wilderness, with no people for miles upon miles, I felt less alone. That sounded crazy whenever I said it out loud, so I seldom did.

Back in my late twenties, after my marriage had ended, I just couldn’t stand being in the city. I fled to the Mojave Desert every chance I got, because in the wilderness, with no people for miles upon miles, I felt less alone. That sounded crazy whenever I said it out loud, so I seldom did.

But this last week, when I read science journalist Florence Williams’ book, The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative, I was happy to learn that I’m not the only one who finds companionship in nature. For instance, the developer of the phone app Mappiness, now with over 60,000 participants, reports that the joy people experience in nature exceeds the amount of joy they feel in cities by about the same amount that being with friends beats being alone.

Williams records her visits with neuroscientists, environmental psychologists, foresters, and other researchers all over the world, each intent on understanding the human-nature bond. Their studies demonstrate that exercising, or in some cases merely being in nature, lowers levels of the stress-related hormone cortisol, reduces sympathetic nerve activity, and lowers our blood pressure and heart rate. Spending just three days in the woods, a group of Japanese businessmen had a 40 per cent increase in NK, or natural killer cells, which protect us from viruses and cancer.

Of course, if we had half a brain, we wouldn’t need scientific experiments to prove that ambling down a dirt or sandy path, breathing the scent of pine or sage, makes us “happier, healthier, and more creative” than walking on concrete, breathing smog. We do in fact have an entire brain, but we primarily use only part of it while working and managing our daily lives, that part being the executive network, our frontal lobes. The neuroscientists Williams interviewed called this “top-down” thinking. In natural environments, we employ what they call “bottom-up” thinking, or the “default network.” Engaging areas of our brain that we have relied on for our first 199,000 year as Home sapiens revitalizes us..

One result, other than improved physical health and less depression, is often a burst of insight we wouldn’t have had if we’d stayed home. Great thinkers from Aristotle to Einstein “walked in gardens and groves to help them think,” as Williams puts it.

The science is in and more is coming in each year, proving that humans need to spend time in the natural world. Sadly, the wild places we evolved in are vanishing. But that’s one reason why we need books like “The Nature Fix” to remind us of who we really are, of where we come from, and to awaken our healthy longing for a healthy world.

June 11, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Taking Notice

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/26-Taking-Notice-Final-Mix.mp3

Today, rather than share my observations of the High Plains, I devised an exercise to encourage you to explore yours. I hope you enjoy it and that it brings you some insight into your relationship with the land. You can do this in your head, but it will be more informative if you do it with your feet, nose, hands, eyes, ears, and, if you’re particularly adventurous, maybe even your tongue.

Today, rather than share my observations of the High Plains, I devised an exercise to encourage you to explore yours. I hope you enjoy it and that it brings you some insight into your relationship with the land. You can do this in your head, but it will be more informative if you do it with your feet, nose, hands, eyes, ears, and, if you’re particularly adventurous, maybe even your tongue.

Drive to a place where intact (not over-grazed) pastureland borders bare farmed ground or a planted field. Stand at the fence facing into the pasture, or if you’re comfortable doing this, crawl through the fence, walk a ways and sit down. Whether it is hot or cold out, windy or calm, smell the air and experience the feel of it on your skin and in your lungs. Take deep breaths. What do you smell?

Let your eyes travel over the grass. Run your hands over it and study it up close. What colors do you see?

If you were an artist would you want to set up an easel and paint a likeness of this place? Is the sky different here than elsewhere? If so, is it the sky’s color or transparency or the shape and height of the clouds or the sheer amount of it that makes it different? Would it be as beautiful without the grass beneath it? What do you hear—the calls of birds or the sounds of engines? If the sounds are other than natural, do you wish they would stay or go away?

Since the Plains are usually sunny, you probably got here on a clear or only partially cloudy day. Regardless, notice the light and the way it affects the colors of the prairie. What is the quality of the light? Is there more light here than other places you’ve visited or lived? What shadows does it cast? Do they lend interest to the landscape? Do they make you wonder what lies beyond the next rise? In what ways does this land affect your mood?

Now leave the pasture and face, or enter, the farmed field next to it. How do you feel now? Would you rather the sun lit the surroundings you were in before or these surroundings? Look at the plowed earth at your feet. How does it compare, in beauty, to the grasses and other plants you were noticing a few minutes ago?

Do the colors of the sky and the ground complement one another as well here as they did in the pasture? If you were a ground-nesting bird, such as a meadowlark or killdeer or a burrowing owl, or if you were a cottontail or a kit fox, would you prefer to live here or in the pasture? In which setting do you feel most at home?

I suggest this exercise as someone who had to leave the Plains to begin to understand how I’d been imprinted by them. Even if your conclusions differ from what I’m sure you can deduce mine would be, I would love to hear your observations. Please share them with me on my website or through this station’s website.

May 24, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/23a-High-On-Spring-Voice-only.mp3

Creative Commons CCO

Every year about this time there comes a Saturday when I begrudgingly forego plans with friends and commit myself instead to working in the yard. This year, that Saturday came last weekend. Respect for my neighbors demanded that I address the unsightly weeds and grass that had grown up in the wood chips around my shrubs.

So there I was, bending my progressively less bendable frame onto my knees, pulling the invaders out one by one. But the weeds kept breaking off instead of coming up by their roots. I fingered an exposed corner of the weed cloth, recalling too well the trouble my compulsive nature had gotten me in before. But the cloth’s surface was covered in a one inch layer of decomposed woodchips. It really needed to be pulled up and re-laid. “Oh to heck with it,” I thought. “Here goes.” I raked away the woodchips and rolled the cloth, matt of composted soil and all, off of the bed.

It wasn’t until late that afternoon, when I was standing in the shower, vigorously scrubbing my hair in hopes of washing away the dirt under my fingernails, that I reflected back over the day and realized that when I’d lifted that matt and breathed the musty smell of moist spring soil, my mood had changed. The job hadn’t been such a big deal after all. In quick order and barely noticing an ache or pain, I had cleaned the weed cloth, replaced it and the wood chips, and moved on to other tasks that hadn’t been on my list. My mailbox pole now had a fresh coat of black paint. Even the wheelbarrow that had sat immovable in the middle of my backyard—its tire flat and its tub full of rainwater, mud, bricks and the stump of a holly bush my son had dug up for me weeks before—was now cleaned and put away.

Scientists have identified the earthy smell that arises from newly turned soil as coming from geosmin, an organic compound that we humans are so attuned to that we can detect just a few drops of it in a swimming pool. It is the same scent that once-parched earth gives off after a rain. If, like me, you find that scent intoxicating, it might be because when we breathe it in, we’re also breathing in Mycobacterium vaccae, a soil microbe that acts much like an anti-depressant, boosting levels of serotonin and reducing stress-related hormones.

Last weekend, on pulling up the weed cloth, I must have taken deep draughts of mood-altering Mycobacterium vaccae into my lungs. Like a lab mouse, who loses its fear of swimming after ingesting the bacteria, I lost my apprehension of the work that lay ahead and even approached it with zeal.

Working in my yard last Saturday might even have made me smarter. Mice dosed with Mycobacterium vaccae run mazes twice as fast as their mates. Maybe that’s why the problem of the wheelbarrow with a flattened tire had suddenly no longer seemed so insurmountable. “Hmm,” I thought. “What if I borrowed a neighbor’s bicycle pump?”

Our Turn at this Earth: The Exploratory Impulse

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/25-Exploratory-Impulse-Final-mix.mp3

Pexels

At age twelve my older brother Bruce knew more about the native plants in our pasture and the birds in our windbreak than I would learn by the time I was thirty. I brought his wrath down on my head once for placing stamps of cardinals and woodpeckers, muskrats and badgers—crookedly, poorly torn, and in the wrong spaces—in his Junior Audubon Society booklet. But for the most part, I didn’t share my brother’s drive to understand the natural world.

Today I wonder why it took me so long to develop an interest in the big outdoors beyond the farmyard. Certainly, my parents gave Bruce freer rein and protected me more because I was a girl. I also had few if any examples, in children’s books or locally, of female adventurers. But for whatever reason, adventurousness and curiosity seemed to be innate in my brother, while they needed a jumpstart in me. I’ve spoken here before about the jolt that awakened my outdoor spirit, which in my case took diving into a frigid mountain lake. By then, I was living in California, so I did most of my roving in the deserts and mountains there.

I got my first opportunity to apply my awakened exploratory impulse back home when I returned to Kansas and farmed with my father for a while in my thirties. Only then did I discover the places where Bruce used to go fishing at fourteen, breaking his driving permit’s “only to school and back” rule. Still today, whenever I manage a trip home, I drive the back roads in search of water, wildlife, and a whiff of the more spirited times before my people arrived, when Indians hunted bison on the flat divides above Ogallala-fed streams.

Speaking to an anthropology class at a western Kansas junior college a few years ago, I was dismayed to discover that, of eight or so students, only one had ever ventured beyond town to explore the land. They hadn’t visited an Indian campsite or taken a drive in the Beaver Valley, where giant native cottonwoods and hackberries shade streams that still run and ducks swim in glassy, tannin-stained pools. They hadn’t fished or waded at Cumberland, another, Thomas County, oasis far out of town. They hadn’t caught minnows, crawdads, frogs or turtles with a net, attempted to identify an unfamiliar bird or noticed that the breeze rustling the leaves of the cottonwoods sounded like running water. Growing up in a rural town, surrounded by countryside, they were no more familiar with or curious about nature than inner city kids who’d never gone hiking or camping.

“Wake up! Go! Get excited,” I wanted to tell them, even though I knew that it had taken a clear, cold lake surrounded by a million acres of wilderness to do that it for me. Wishing them a metaphoric lake to dive into, I left the campus that day and did what I do every time I have a free moment in Kansas—drove out to the countryside to see what I could discover.

May 2, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: After Sand Creek

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/23-After-Sand-Creek-Final-Mix-MP3.mp3

Cherry Creek Memorial, Alan Hutchins Photo

“Your grandparents started out right over there,” Tobe Zweygardt said, pointing to a farmed hillside in the distance. It amazed me how much information Tobe, an elderly retired farmer, stored under that billed cap he wore. I knew my father had spent his early childhood in Cheyenne County, but until then hadn’t known where.

The terrain along Cherry Creek was what my father used to refer to as desert “scrub,” the kind of land I loved—all jutting boulders, cactus and yucca—and that he had no use for, because it wasn’t arable. Groundwater irrigation on flatter land to the west had reduced the flow to a mere trickle, but the creek once had enough water to sustain 3,000 Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux through the winter of 1864 to 1865.

On the bluff above us, Tobe had placed one of his iron silhouettes, this one a life-sized mounted Indian holding his lance erect. After the massacre of 160 to 200 peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho at Sand Creek, Colorado, the war pipe had been passed among the plains tribes. They had gathered here to prepare for war. As one Cheyenne chief, Leg-in-the-Water, put it “The white man has taken our country, killed our game; was not satisfied with that, but killed our wives and children. … We have now raised the battle-axe unto death.”

“I brought you a copy of that list Mr. Sipes gave me,” Tobe said, reaching into his pocket and pulling out a folded sheet of paper. My eyes drifted down the names of the 95 refugees who had made the trek from Sand Creek. Names like Roman Nose Spotted Horse, born 1860. He would have been only four in 1864. Sage Woman, born 1855, would have been nine.

“Mr. Sipes could point to where each clan had camped,” Tobe said, jabbing his own finger toward spots up and down the creek. John Sipes, a Southern Cheyenne man who had come to see where his grandparents had gone after surviving the massacre, had known all of that just from stories handed down to him! And on the day before, I’d driven right past our old farmstead on the Sherman-Cheyenne County line without even recognizing it. I’d been taking back roads, soaking up more Indian history from the markers Tobe had erected than I’d learned in school. I only realized where I was when I came to a familiar bridge over the dry bed of the Middle Beaver. A map of the Sand Creek refugees’ route to Cherry Creek showed them crossing the Middle Beaver near that spot. It excited me to think that, continuing north, they might have passed over the land that would become our farm+.

Now, I gazed at the hill where my father had been born. Many Cheyenne had died fighting to keep this land. And we had sold our farm and moved away of our own free will. Was that why I had such an insatiable appetite for Indian history? It seemed to be filling in the connections to the land that we had ourselves erased. Connections that I needed in order to feel whole.

April 6, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Indelible Infamy

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/22-Indelible-Infamy-Final-MIX-INT-Compressed.mp3

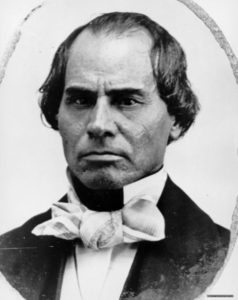

William Bent

It “…was the worst blow ever struck at any tribe in the whole plains region, and this blow fell upon friendly Indians.” That is how one survivor, George Bent, begins his description of the massacre that took place on November 29, 1864 in southeastern Colorado. Bent was the son of Owl Woman, whose father was a prominent Cheyenne chief, and William Bent, a famous fur trader of the era. Thanks in part to the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, which opened to the public in 2007, many more people know about that shameful day in settlement history than in my childhood. Although my hometown was less than a hundred miles from Sand Creek, it was never mentioned.

To briefly summarize: At dawn on November 29, 1864, U.S. Army Colonel John Chivington and 700 men of the Colorado Cavalry attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho, murdering between160 to 200 people, approximately two-thirds of whom were women, children, and infants. The peace chief Black Kettle had chosen to camp at Sand Creek because Colorado’s Governor Evans had assured him that his people would be safe there.

Bent fled with others upstream and dug a pit in the sand to hide in. Soldiers fired howitzers into the pits, killing most who took refuge there, but Bent survived. Of the night that followed, he wrote, “There we were, on that bleak, frozen plain, without any shelter whatever and not a stick of wood to build a fire with.” He describes how the able-bodied tried to prevent the wounded from freezing to death by covering them with their own blankets and robes, or with handfuls of grass.

Riders who had escaped the attack and raced the forty miles to Big Timbers—a Cheyenne Dog Soldier camp on the Smoky Hill River, in Kansas—returned the next morning with mounts and blankets for the survivors. “As we rode into camp,” Bent wrote, “everyone was crying, even the warriors and the women and children screaming and wailing. Nearly everyone present had lost some relations or friends, and many of them in their grief were gashing themselves with their knives until the blood flowed in streams.”

Chivington’s men did not stop at killing their victims, but went among them afterward, slicing away scalps and body parts as trophies. A Congressional investigation that followed found it “…difficult to believe that beings in the form of men, and disgracing the uniform of United States soldiers and officers, could commit or countenance . . . such acts of cruelty and barbarity.”

Reading of these horrors, I was consoled somewhat to learn that two officers refused to participate in the massacre and ordered their men to stand down. One of them, Captain Silas Soule (Sole), was among the first to report the crimes. While an Army Judge censured Chivington for committing “cowardly and cold-blooded slaughter, sufficient to cover its perpetrators with indelible infamy,” Chivington was out of the military by then, and no charges were ever brought against him or his men.

For additional information, visit:

https://www.nps.gov/sand/planyourvisit/upload/SAND_S1_X3.pdf

March 29, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: What I Never Learned in School

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

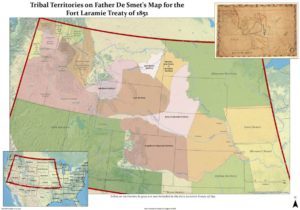

I’m not sure why this never dawned on me when I was a kid, but not until well into my adulthood did I put two and two together and realize that Cheyenne County, just north of our Kansas farm, was—duh!—named after the tribe that used to live there. Indeed, the 1851 Horse Creek treaty, signed at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, had granted the Cheyenne and their allies, the Arapaho, the land where I grew up, along with all the land west from there into the Rocky Mountains.

I’m not sure why this never dawned on me when I was a kid, but not until well into my adulthood did I put two and two together and realize that Cheyenne County, just north of our Kansas farm, was—duh!—named after the tribe that used to live there. Indeed, the 1851 Horse Creek treaty, signed at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, had granted the Cheyenne and their allies, the Arapaho, the land where I grew up, along with all the land west from there into the Rocky Mountains.

And when my family visited Smoky Gardens, a little reservoir on the Smoky Hill River south of my hometown, Goodland, I had no idea we were picnicking just a half day’s horseback ride downriver from Big Timbers, the favorite campsite of a famous Cheyenne warrior society, the Dog Soldiers. I don’t recall learning much about the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush either, which began in 1859. According to the historian Donald J. Berthrong, less than half of the estimated 100,000 ‘59ers ever reached the gold fields. Instead they began to “inundate the lands of the Cheyenne and Arapaho.” To defend their buffalo hunting grounds, the Dog Soldiers and other warriors raided the new settlements, and were attacked in turn. Did my textbooks leave all this stuff out? If not, how was it I failed to realize I was growing up in a place where the Plains Indian Wars once raged?

Frequently in frontier days, the invading culture would sign one treaty then notice something it wanted—gold, or good farm land, or a railroad through prime hunting grounds—and draw up a new one. Accordingly, in 1861, the Treaty of Fort Wise sought to force the Cheyenne and Arapaho onto a tiny southeastern Colorado reservation one-thirteenth the size of the lands ceded to them in the Horse Creek Treaty. Like the majority of their tribesmen, the Dog Soldiers refused to sign and didn’t honor the new boundaries.

As hostilities between Indians and settlers intensified, Colorado governor John Evans ordered all “friendly” Indians in the region to report to military posts or be subject to attack. Peace chiefs Black Kettle of the Cheyenne and Niwot of the Arapaho, along with 750 followers, mostly women and children, set up a village on Sand Creek, near Fort Lyon. Evans assured them they would be safe there.

Of all the history I didn’t learn while growing up, my ignorance about what happened at that Sand Creek encampment on November 29, 1864 troubles me most. I learned about it only later in adulthood when I began to wonder about the people who had lived in the region I called home before me.

The history is better known today, but if, like me, you grew up uninformed about it and haven’t filled in the blanks since, I encourage you to type these words into your browser: “Sand Creek 1864.” Even though the facts themselves are very dark, the only way to vanquish darkness is to open a curtain or turn on a light.

I will share more of what I’ve learned next week.

March 19, 2018

Out Turn at this Earth – A Bright Glimpse into the Dim Past

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

Bison antiquus skeleton, Nebraska State Museum of Natural History

My cousin Mark Jones ranches in eastern Colorado on what were once the headwaters of the Arikaree, a tributary to the Republican River. Mark calls it the Ricaree. “Was there water here in the Ricaree when you were a kid?” I asked him.

“Oh yeah,” he said.

“Is there ever water in it now?”

“Hardly ever.”

We sat in his windowless dining room, once a sod house. In the late 1800s a rambling two-story house had been built around it. I was enchanted by the ceiling, still thatched in reeds and cottonwood limbs that the original homesteaders had cut along the banks of the river. His grandmother had oiled the thatching, and it glowed red in the light cast by the table lamp.

Although I remembered attending family reunions on this ranch, I didn’t remember Mark. I’d come to hear about the trove of ancient buffalo bones and projectile points that his father, Bob Jones, had discovered in 1972. The resulting Smithsonian dig had been the subject of a National Geographic article.

The irony didn’t escape me that the bison kill site from the Hell Gap culture of 10,0000 years ago had been exposed while Mark’s father was excavating for the installation of a center pivot irrigation sprinkler. It was groundwater irrigation that would ultimately dry out the river on which those Paleo-Indians had depended. Every tribe after them, including the river’s namesake, the Arikara, depended on it too. So had the bison—which proved to be Bison antiquus, a larger ancestor of Bison bison, the animals we commonly refer to as buffalo.

If we had satellite images going back to the 1940s, when high-volume irrigation came to the plains, they would show the headwaters of virtually every stream withering to mere ponds, then the ponds blinking out, west to east, one by one. That’s 10,000 years of reliable water depleted in less than a hundred. Because the High Plains slope downhill from the Rocky Mountains, the westernmost water disappears first.

“It was a fun, busy time,” Mark said, recalling the team of archaeologists who descended on the ranch after his father happened onto the Hell Gap site.

One determined grad student stayed on after the others left. “I’d see him driving up this side of the valley one evening, then up the other the next,” Mark said. The grad student’s efforts paid off one evening when he stuck his shovel in the ground and broke a seven inch spear point from the Upper Republican period. Beside the point, he found yellow war paint so fresh it could still be smeared.

Mark’s story, told in the reddish glow from the reeds overhead, gave me a bright glimpse into the thousand year old Upper Republican culture, which had been named after the river into which the Arikaree does still flow, but at less than half its original volume. The much older Hell Gap culture got its name from the southeastern Wyoming valley where its artifacts were first discovered, beside a small stream.

Indians had always, by necessity, camped and hunted near places where water flowed. But not even reeds could grow on Mark’s ranch anymore.