Julene Bair's Blog

August 27, 2020

Our Turn at This Earth: What We Toss Comes Back to Haunt Us

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

“Malaysia to Send 3000 Tonnes of Plastic Waste Back to Countries of Origin.” So read a recent headline. Apparently, the Malaysians are tired of being a dumping ground for the world’s trash. They are not alone. China, which used to take 70 percent of the hardest to recycle plastic, is refusing it now too.

“Malaysia to Send 3000 Tonnes of Plastic Waste Back to Countries of Origin.” So read a recent headline. Apparently, the Malaysians are tired of being a dumping ground for the world’s trash. They are not alone. China, which used to take 70 percent of the hardest to recycle plastic, is refusing it now too.

Imagining all that plastic junk being dumped back on the countries it came from reminds me of a science fiction story I read as a teenager. “Dusty Zebra,” by Clifford D. Simak, was about a guy who had discovered a magic portal into another dimension. The portal appeared to be nothing more than a dot on the top of his desk. But whenever he set something there it vanished, soon to be replaced with a mysterious object from that other realm. One of these objects made dust disappear.

Soon a deal was struck. The earthling had no idea what his trading partner did with the thousands of tiny zebra-shaped trinkets he sent through the portal, but he charged a handsome price for the thousands of dust removers he got in exchange. He became rich, never stopping to think what might be happening to the vanishing dust. Not, that is, until it all came back to Earth, in one big dump.

“Here’s your cussed dust,” whoever sent it back seemed to be saying. “We don’t want it!” It was a well-deserved comeuppance, a joke on us. The implied commentary seemed profound to me even at age thirteen, and that was before we’d fully embraced the notion of throw-away plastics. There were no disposable lighters, no Styrofoam or clamshell containers meant to be tossed as soon as their contents were consumed.

The “big lie about plastic,” as one LA Times commentator wrote, “is that you can throw it away. … [T]hat’s not true; there is no ‘away.’” All of the plastic refuse we have been tossing is coming back to haunt us now, just as the dust came back in Simak’s story. I have seen Caribbean beaches littered in plastic refuse from their shorelines back into adjacent palm forests– a depressing sight to say the least, a real downer when you thought you were visiting paradise.

The hardest to watch 60 Minutes episode I ever saw was about albatrosses on Midway Atoll, a U.S. Territory in the Hawaiian Island chain. I marveled to see the beautiful birds engaging in a courtship ritual as graceful and elaborate as ballet. But the albatrosses have been dying in huge numbers. It sickened me to discover why. Autopsies on the birds reveal stomachs stuffed full of fragments of broken plastic. By 2050, scientists now predict, there will be more plastic, by weight, in the oceans than fish.

Even though it takes plastic over 400 years to decompose, it sheds tiny micro-particles all along the way. These appear in the milk babies drink from plastic bottles, in bottled water, in the fish we eat, in our air. The toxins in plastic are suspected of causing cancer, birth defects, immune and endocrine system issues, and developmental issues in children.

New types of biodegradable plastics need to be further developed. Until then, manufacturers should be required to source only plastics that can be recycled easily and more than once, we shouldn’t be using plastic containers for food or beverages, plastic bags should not be available in stores, and curbside recycling should be available everywhere – not just in a few big cities. We can all advocate for these and other changes, but most importantly we need to change our own mentality. We buy water in plastic bottles, carry goods home in plastic bags, and accept Styrofoam containers for take-home leftovers, then throw them all away only at our own peril.

August 13, 2020

Our Turn at This Earth: Common Sense

https://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2-20-Common-Sense-Final-Mix.mp3

Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

I grew up with a healthy respect for a form of intelligence my mother referred to as common sense. Ever since that Kansas childhood, I have equated the place, and the people in it, with that theory of knowledge, which holds that you can know in your bones a whole lot of stuff without having to be taught. If it starts raining, then you know to take shelter. If you open a pasture gate, you close it behind you.

I grew up with a healthy respect for a form of intelligence my mother referred to as common sense. Ever since that Kansas childhood, I have equated the place, and the people in it, with that theory of knowledge, which holds that you can know in your bones a whole lot of stuff without having to be taught. If it starts raining, then you know to take shelter. If you open a pasture gate, you close it behind you.

If you have limited income, then don’t charge your purchases on a credit card, or if you do, pay the entire balance each month. My parents seemed to have a built-in alarm system that shouted warnings at them whenever they were tempted to spend more than they earned. Living within their means was one of the cardinal rules they lived by.

“It’s just common sense,” Mom was in the habit of saying. But whether common or not, their practical intelligence was a very useful character asset that allowed my parents to avoid painful consequences and protect their own interests – and perhaps not all that common after all, especially when you consider how often we humans act against our own interest.

This is especially true when we act collectively. Take, for instance, the economic system that we collectively created. Predicated on the notion of perpetual growth, it must continually expand while every one of our increasing number strives for an ever-higher standard of living. If the Gross Domestic Product fails to grow at the two to three percent annual rate considered ideal, economists sound alarms. But the real cause for alarm is the growth, not the lack of it.

All of that expansion would be fine if the resources it depends on were also expanding, but that is impossible. We are living beyond our means on a finite planet. We are depleting and polluting our water and soils; using up our minerals; killing off other species, many of them essential to our own food supply; and destabilizing our own climate. If that’s not the opposite of common sense, I don’t know what is.

I think the fact that we are spending beyond our planetary means is obvious to many more people than is generally believed. But people feel overwhelmed by the magnitude of the problem. Instead of listening to their own internal alarms – “Danger! Danger! Life support systems failing!”—they try to ignore the warnings.

How can we slow down, reform, or turn around a world economy? What can any individual do? Better to just pretend we are not engaged in an act of mass suicide, one that will come to its full and, by then, all too obvious, conclusion in our grandchildren’s, or our great-grandchildren’s, lives.

“It’s just common sense.” Whenever my mother said this, she seemed to imply that this down-to-earth form of intelligence was an attribute only of common men and women – ordinary people who could navigate the real world more adeptly than those who were born with silver spoons in their mouths or who have gotten so educated that they are no longer capable of understanding the basic facts of life. That’s an appealing thought, one I would like to be true, because ordinary people need just such an advantage to stave off the efforts of those who stand to gain more wealth and power by concealing and distorting the facts.

These forces want us to believe there is no threat to our environment, and therefore no threat to us. They are adept at manipulating us into thinking the only real danger is to our financial futures if we heed the environmental warnings.

The fact that such greed is rampant and determined to keep our eyes closed should be all the reason we need to open them wide.

August 11, 2020

Our Turn at This Earth: Fences of Our Own Making

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

One of the most heartbreaking essays I ever read was by Alice Walker, about a lonely horse named Blue. One joyful day, a mare arrived to share his pasture, and Blue entered a brief period of bliss. A few months later, after a trailer came and carried Blue’s best friend away, he galloped “furiously” around and around his pasture, “whinnied until he couldn’t,” and “tore at the ground with his hooves.” He was so distracted by grief that he wouldn’t even take the apples Walker offered him anymore.

One of the most heartbreaking essays I ever read was by Alice Walker, about a lonely horse named Blue. One joyful day, a mare arrived to share his pasture, and Blue entered a brief period of bliss. A few months later, after a trailer came and carried Blue’s best friend away, he galloped “furiously” around and around his pasture, “whinnied until he couldn’t,” and “tore at the ground with his hooves.” He was so distracted by grief that he wouldn’t even take the apples Walker offered him anymore.

Horses aren’t the only ones whose hearts ache when they are cut off from their own kind. I’m sure many people have suffered pangs of loneliness while sheltering in place during this COVID-19 crisis. For some, the emotion may have come as quite a shock.

I say this because I remember that my first serious encounter with loneliness, at 26 and recently divorced, shocked me. Accustomed to working in the busy office of an audio studio that my husband and I had owned, I now worked alone as a bookkeeper and returned to my empty house each evening as the fog rolled in, turning San Francisco gray. I’d never lived alone before. The unbearable panic that arose in me felt like it was being generated by an internal enemy.

Having grown up on the western Plains, I bought into the western mythology of the entirely self-reliant individual. Loneliness seemed like a weakness to me, so I set out to defeat it.

I’d been on many camping trips in the Mojave Desert. I loved its craggy mountain ranges, the exhilarating smell of sage, how quiet it was and how reliably sunny, especially after years San Francisco fog. It seemed the perfect place to wage my battle. Today it strikes me as a little more than odd – crazy perhaps? – that I had enough courage to live alone in rugged desert mountains but was afraid to pick up the phone and ask someone to lunch or dinner.

As you probably guessed, I failed miserably at overcoming loneliness. While I never tired of the desert’s dramatic beauty, inside, I was still running up and down a fence line constructed of my own social ineptitude. As much a herd animal as Blue, I needed a friend.

For the first couple of months, the only people I interacted with were store clerks when I drove to town for supplies. But gradually, humans began emerging from canyons and crags. The foreman of a nearby ranch arrived “to see if I needed anything,” he said, but I think he was really checking up on my safety. My nearest neighbor, from two miles down the road, came to tell me I might want to move my trailer off the hill, lest it topple in a windstorm. A hermit couple dropped in on their way to town to ask if I wanted them to get me anything. A gifted, idiosyncratic artist who lived in a rock hovel suitable for a gnome liked to share his work and thoughts. Soon, I started getting invitations to potlucks and roundups on ranches. Most importantly, I learned that there was no shame in hanging out to chat after picking up a few items at the general store 25 miles away. All the desert dwellers did that.

That I had to move to a sparsely inhabited desert to learn that loneliness is not a weakness might seem ironic, but it actually makes perfect sense. People were like diamonds there, rare and hard to come by. Therefore, they valued one another.

Just as hunger tells us, “Eat!” loneliness tells us, “Connect!” That is difficult now. Being physically close to others can be dangerous. But there are ways. We just need the courage to pick up the phone, attend a ZOOM meeting, or stop on a walk and chat with a neighbor at a safe distance.

As humans, most of us are very lucky. We have options that Blue didn’t.

Fences of Our Own Making

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

One of the most heartbreaking essays I ever read was by Alice Walker, about a lonely horse named Blue. One joyful day, a mare arrived to share his pasture, and Blue entered a brief period of bliss. A few months later, after a trailer came and carried Blue’s best friend away, he galloped “furiously” around and around his pasture, “whinnied until he couldn’t,” and “tore at the ground with his hooves.” He was so distracted by grief that he wouldn’t even take the apples Walker offered him anymore.

One of the most heartbreaking essays I ever read was by Alice Walker, about a lonely horse named Blue. One joyful day, a mare arrived to share his pasture, and Blue entered a brief period of bliss. A few months later, after a trailer came and carried Blue’s best friend away, he galloped “furiously” around and around his pasture, “whinnied until he couldn’t,” and “tore at the ground with his hooves.” He was so distracted by grief that he wouldn’t even take the apples Walker offered him anymore.

Horses aren’t the only ones whose hearts ache when they are cut off from their own kind. I’m sure many people have suffered pangs of loneliness while sheltering in place during this COVID-19 crisis. For some, the emotion may have come as quite a shock.

I say this because I remember that my first serious encounter with loneliness, at 26 and recently divorced, shocked me. Accustomed to working in the busy office of an audio studio that my husband and I had owned, I now worked alone as a bookkeeper and returned to my empty house each evening as the fog rolled in, turning San Francisco gray. I’d never lived alone before. The unbearable panic that arose in me felt like it was being generated by an internal enemy.

Having grown up on the western Plains, I bought into the western mythology of the entirely self-reliant individual. Loneliness seemed like a weakness to me, so I set out to defeat it.

I’d been on many camping trips in the Mojave Desert. I loved its craggy mountain ranges, the exhilarating smell of sage, how quiet it was and how reliably sunny, especially after years San Francisco fog. It seemed the perfect place to wage my battle. Today it strikes me as a little more than odd – crazy perhaps? – that I had enough courage to live alone in rugged desert mountains but was afraid to pick up the phone and ask someone to lunch or dinner.

As you probably guessed, I failed miserably at overcoming loneliness. While I never tired of the desert’s dramatic beauty, inside, I was still running up and down a fence line constructed of my own social ineptitude. As much a herd animal as Blue, I needed a friend.

For the first couple of months, the only people I interacted with were store clerks when I drove to town for supplies. But gradually, humans began emerging from canyons and crags. The foreman of a nearby ranch arrived “to see if I needed anything,” he said, but I think he was really checking up on my safety. My nearest neighbor, from two miles down the road, came to tell me I might want to move my trailer off the hill, lest it topple in a windstorm. A hermit couple dropped in on their way to town to ask if I wanted them to get me anything. A gifted, idiosyncratic artist who lived in a rock hovel suitable for a gnome liked to share his work and thoughts. Soon, I started getting invitations to potlucks and roundups on ranches. Most importantly, I learned that there was no shame in hanging out to chat after picking up a few items at the general store 25 miles away. All the desert dwellers did that.

That I had to move to a sparsely inhabited desert to learn that loneliness is not a weakness might seem ironic, but it actually makes perfect sense. People were like diamonds there, rare and hard to come by. Therefore, they valued one another.

Just as hunger tells us, “Eat!” loneliness tells us, “Connect!” That is difficult now. Being physically close to others can be dangerous. But there are ways. We just need the courage to pick up the phone, attend a ZOOM meeting, or stop on a walk and chat with a neighbor at a safe distance.

As humans, most of us are very lucky. We have options that Blue didn’t.

July 9, 2020

Our Turn at this Earth: Joy

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

Susan Davis Photo

As a young woman, I met a guy who consulted the I Ching whenever he needed to make a decision. When he consulted that ancient Chinese book of divination about me, the result seemed beyond coincidental. The answer he got fell under a heading that, in English, meant “The Joyous, Lake.” It thrilled and flattered me that the oracle had made that connection. The greatest joy in my life was swimming in mountain lakes.

I still love nothing more than swimming in a cold, clear lake on a hot summer day. The heat makes taking the plunge irresistible. In my book, The Ogallala Road, I described lying on a boulder beside a lake in the high Sierras:

“I hang my arm off the edge, and, trailing my fingers through the water, begin a slow, delectable flirtation. The high-altitude sun presses my back as with a dry iron, while below me, riffles slap rock. Glare refracts off the water, dappling my arms and flashing hypnotically on my retinas. I am irradiated, intoxicated.”

When I couldn’t resist anymore and dove into that lake, I shot back to the surface with a scream. But, as with all my dives into mountain water, my skin soon adapted to the cold. I relished the water’s silken feel on my skin. And, swimming with my eyes open as I always do, I loved watching my hands and arms, radiant and sunlit from above, ply through the clear water.

Mountain lake water is always too cold to stay in it for long, yet it takes an act of sheer will to get out before hypothermia sets in. In my book, I wrote about how it felt to lie down on a warm boulder after a cold swim: “…the sun’s high heat penetrates me, lifting and nullifying the lake’s deep cold. Enlivened, awakened, I savor all to which I’ve been reborn – the rasping call and obsidian sheen of a raven slicing the depthless blue above me, the tickle of my arm’s sun-bleached hairs as I drag my lips over them, breathing my skin’s smell. The fragrance doesn’t come only from the lake, but from granite, ozone, and pine.”

The joys of this favorite pastime are the reason a picture in a recent digital issue of the New York Times, of a woman sunbathing on a natural rock bridge over a large body of indigo water, caught my eye.

I hit the Facebook link at the top of the page and posted the picture along with the accompanying article. I seldom post anything on Facebook, but it seemed well worth making an exception for this image, which brought up so many memories of my joyful swims in similarly stunning places. The post got a few immediate likes and comments but when I checked back the next day to see if there had been any other responses, I was greeted by a note from the Facebook censors telling me that I had violated their community standards. The image had been removed and my posting privileges would be suspended for 24 hours.

At first I was surprised that a photo that had run in one of the nation’s foremost newspapers would be considered inappropriate for Facebook, but then I read the rest of the note: “We restrict the display of nudity or sexual activity,” it explained, “because some people in our community may be sensitive to this type of content.”

Oh. It was a distant shot of her, taken from high above, but I guessed the woman was pretty naked.

This may seem strange to you, but her nudity hadn’t even registered on me, this even though the title of the article was “The Splendors of Lying Naked in the Sun.” This is just an example, I guess, of how overpowering personal experience can be. For me, the photo was not about the woman’s nakedness. It was about water, rock and sun. It was about the “sun’s high heat lifting and nullifying the lake’s deep cold.” It was about joy.

June 25, 2020

Our Turn at This Earth: A Moment to Relive Forever

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

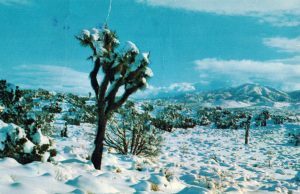

Snow in the Mojave Snapshot

If you could relive just one moment throughout eternity, which one would you choose? I asked myself that question a few weeks ago, as I watched After Life, a movie by the Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda. In this movie, people who have recently died are instructed to choose a moment from their lives that will then be recreated on film and replayed, again and again, forever. On each viewing, it would be as if they were experiencing the moment for the first time.

I would be among the lucky ones in Hirokazu’s’s version of the afterlife, because I have many good memories from which to choose. The most exhilarating ones come from my desert period, which began in my late twenties and lasted about five years. On a camping trip in Death Valley, I fell in love with the softly curved, cream-colored dunes that stretched across the basin toward the mysterious reaches of the snow-capped Panamint Mountains. It wasn’t just the visual grandeur that grabbed me, but the freshness of the air and pervasive silence that filled that immense space. I hadn’t felt such peace since my Kansas farm childhood when I had taken sunlit silence, clean air, and wide vistas of land and sky for granted.

But because the desert was too rugged and dry to be farmed, it could not be tamed, and its natural beauty and wildness captivated me. Soon, I began entertaining the idea of leaving the city and moving to the desert. I explored deserts all the way from Oregon to New Mexico, and finally found my new home in the Arizona-Nevada-California border country south of Death Valley: a little rock house overlooking five mountain ranges, without another manmade structure in sight.

Even though I have many cherished desert memories, it didn’t take me long to decide which moment I would choose if I had to relive it forever.

It was a bright January morning. I was in the driver’s seat of my boxy red Land Cruiser, a “Jeep” style vehicle that had so many years on it that its paint had oxidized. I couldn’t touch the hood without my fingers coming away stained red. My best friend, Beatrice, sat beside me in the passenger seat. She’d ridden down to the Mojave with me to help me set up housekeeping on the rock house hill. I wouldn’t be living in the house itself anytime soon. It had a collapsed ceiling and no windows. The next day, Beatrice and I would drive 65 miles into Needles, purchase a small house trailer, and tow it back up the hill. At the moment, we were on our way to visit the elderly ranching couple who owned the property and had consented to let me live there in exchange for fixing up the house.

Snow had fallen the night before. Yes, it does snow in the Mojave, but it’s a rare treat. We had spent the night in a tent beside a gnarly, windswept juniper tree whose branches were now white and drooping.

“Let’s go!” Beatrice said. “Brr! Roll your window up.” But I was fixated on the way my side mirror framed an image of the yellow-granite house, destined to become the most beloved home I would ever have. I couldn’t get over the way the finite image of the rock house reflected in the mirror was framed by the nearly infinite vision beyond us, of snow-dusted juniper, cholla cactus, and sage leading into the sky’s cobalt blue.

My memory of that moment has been so vivid over the last forty years that I was certain I’d taken a picture out the Land Cruiser’s window. I could have sworn I’d seen it often in my desert photos. But when I turned the pages of those albums, it wasn’t there. It seems I don’t need a picture to remember it. Nor would I need a movie to remember it by if I died tomorrow.

It was a bright new morning, a new day in the life of my soul, exactly what one hopes for in the afterlife.

This commentary was inspired by another essay called “Hereafter, Faraway,” by Viet Thanh Nguyen, who was also responding to Kore-eda’s film. It was one of the best pieces I’ve ever read in the The New Yorker, and that is saying a lot.

June 18, 2020

Our Turn At This Earth: The Source of All Life

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

Almost all of the watercourses on the High Plains are fed by the Ogallala aquifer. Each one of them creates its own paradise. Red-winged blackbirds trill from their perches atop tall reeds. Deer, pheasants, wild turkeys, and other wildlife wend through thick meadow grasses. Cottonwood and hackberry trees shade the water, which is usually so clear you can see fish swimming in it. In the journal of his 1843 expedition through the High Plains, the explorer John C. Fremont described one such place as a “birded glen.” Standing in one of those lush, verdant meadows, looking through the trunks of trees onto hot, dry hillsides that rise above them, always brings home to me the fact that water is indeed the source of all life.

Almost all of the watercourses on the High Plains are fed by the Ogallala aquifer. Each one of them creates its own paradise. Red-winged blackbirds trill from their perches atop tall reeds. Deer, pheasants, wild turkeys, and other wildlife wend through thick meadow grasses. Cottonwood and hackberry trees shade the water, which is usually so clear you can see fish swimming in it. In the journal of his 1843 expedition through the High Plains, the explorer John C. Fremont described one such place as a “birded glen.” Standing in one of those lush, verdant meadows, looking through the trunks of trees onto hot, dry hillsides that rise above them, always brings home to me the fact that water is indeed the source of all life.

This is evident on the semi-arid High Plains, but even more so in the desert Southwest, and that is probably why many of the native desert people describe humanity first emerging onto the surface of the earth through a spring. In the Laguna Pueblo myth, the people couldn’t reach the surface until an antelope butted a hole onto it and a badger clawed the hole wider.

The Laguna author Leslie Marmon Silko explains that the myth is not meant to be taken literally, but metaphorically. As she puts it, “Life on the high arid plateau became viable when the human beings were able to imagine themselves as sisters and brothers to the badger, antelope, clay, yucca, and sun. … Only then could they become a culture whose survival remained stable despite the vicissitudes of climate and terrain.”

“Stable” is a key word in Silko’s explanation. That the Pueblo cultures and their ancestors have survived in the desert for thousands of years proves the wisdom of their spiritual worldview, which recognizes their kinship and interdependence with everything in their environment.

By contrast, my people, rather than tracing our identity and survival to the natural world, tend to see ourselves as autonomous individuals who must master and subdue nature in order to survive. That is why, only a century and a half after pioneers settled on the High Plains, most of those birded glens that Fremont so beautifully described no longer exist. It is why the groundwater under agricultural land is drying up, and why most of the prairie grasses and the complex systems of interrelated animal and plant life that greeted us on our arrival are now gone.

Anthropologists believe that the Pueblo People descended from the paleo-Indians who hunted and gathered in the desert Southwest during the ice ages. Evidence of their ancient presence can be seen in the images of bighorn sheep, antelope, birds and hunters that they carved into sandstone walls.

My people’s arrived on the plains much more recently. While our survival depends just as much on water as the Pueblo People’s survival does, we don’t trace our origins to the spring-fed streams where the first settlers homesteaded, nor to the aquifer that fed those streams and that our windmills pumped, but to Europe, a far off land that few of us have ever seen. In this sense, we are like orphans, disconnected from our life source and largely unaware of our kinship with all of the other animals and plants that owe their existence to the same water.

But unlike the mothers of orphan children, ours did not pass away, although we do put her in danger by failing to recognize our connection to her. This is a situation that can be corrected. All we have to do is open our eyes. We see her each time we turn on a faucet. She nurtures us each time we take a drink.

June 11, 2020

Our Turn At This Earth: What Looking At the Land Tells Us About Ourselves

Author Leslie Marmon Silko

Until I read the Native American writer Leslie Marmon Silko’s essay “Landscape, History and the Pueblo Imagination,” the word “landscape” had strictly positive connotations for me. Hearing it, I imagined broad vistas of land and sky. I grew up enthralled by such vistas and still am. But Silko’s essay rang so true to me that, ever since reading it, I can’t come across the word “landscape” without questioning the way that my culture looks at the world.

Silko explains that the word, as it has come down to us, implies that “the viewer is … outside or separate from the territory he or she surveys.” “Viewers,” she continues, “are as much a part of the landscape as the boulders they stand on. There is no high mesa edge or mountain peak where one can stand and not immediately be part of all that surrounds.”

Boulders, mesas, and mountains are features of the high desert Southwest, where Silko’s Laguna Peublo people have lived for over 3,000 years. Particular examples of such land forms figure prominently in stories passed down from one Laguna generation to the next. These stories teach children that they are intertwined with the land and with everything that exists above, upon, and in it.

I also grew up feeling solidly held within the landscape of my birth. But this didn’t prevent me from moving away as soon as I graduated high school. A decade and a half later, when I returned to live in western Kansas for a while, I was shocked at the changes. Not very many farmers kept livestock anymore, and most of them, like my parents, had left their farms and moved to town. Much more of the native prairie had been plowed, and the water that had made my ancestors’ settlement possible was being used up.

Our 150 years as plainspeople is short compared to the Lagunas’ thousands of years in the desert, yet we are well on our way to drying out the streams that once watered millions of buffalo, elk, deer, and antelope and the humans who once depended on those herds for survival.

Silko explains that the images of elk and antelope that the ancients scratched or painted on stone walls focused the people’s prayers and concentration on the animals and guided the “hunter’s hand.” Similarly, the archetypal images of squash blossoms on Laguna pots, with their four symmetrical petals and four stamens, linked the images to the four cardinal directions and to, as Silko writes, “a complex system of relationships which the ancient Pueblo people maintained with each other, and with the populous natural world they lived within.” I take this to mean that they understood how critically interdependent they were with everything in their environment, and that those relationships were spiritual.

It may seem ridiculous to those of a different, or of no, religion to think that successful hunting or bountiful harvests could be elicited through ritualistic depictions of plants and animals on boulders and pots. But it would also seem ridiculous to the Laguna that we could plow under almost all of our native grasslands and pump massive amounts of groundwater without understanding that the consequences to ourselves would be severe.

The Silko essay hit home with me because I knew that thinking we are separate from the land had made such destructive practices possible. We humans all want to be part of something larger. We want to belong. We want to be important in the scheme of things. Little do many of us know that we are part of something larger. We do belong.

And we are important, so much so that we are capable of destroying, or saving, the natural systems upon which we depend. Which it will be is up to us.

May 28, 2020

Our Turn At This Earth: The Night Darkness Returned to the Farm

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

In my mid-thirties, while living back on my family’s Kansas farm after spending many years away, I couldn’t stand the automatic dusk-to-dawn yard light that blinked on each evening. In my childhood, we turned our yard light off some evenings just so we could gaze at the stars, and we always turned it off before we went to bed. Imagining what might lurk in the darkness had given the night its edge. Now the wash of dreary, fluorescent light robbed the night of mystery and the sky of its wonder and power.

In my mid-thirties, while living back on my family’s Kansas farm after spending many years away, I couldn’t stand the automatic dusk-to-dawn yard light that blinked on each evening. In my childhood, we turned our yard light off some evenings just so we could gaze at the stars, and we always turned it off before we went to bed. Imagining what might lurk in the darkness had given the night its edge. Now the wash of dreary, fluorescent light robbed the night of mystery and the sky of its wonder and power.

How should I spend such a night? Inside, basking in the equally dismal light of a tv? While I enjoyed some television, I didn’t want a constant diet of it. I wanted to go outside and be dusted in the milky light of the moon and stars, not that yard light’s sickly fluorescent glow. But the light didn’t even have an off switch. How could my aunt and uncle, who lived across the farmyard from me and who had lived in the country most of their lives, not miss the darkness and stars as much as I did? How could the people living on surrounding farms, where lights also blinked on at dusk, not miss prairie darkness?

After months of torment, I finally got my opportunity to restore night to our farm when my father bought a new seed drill. Folded up for transport, it couldn’t pass beneath a wire that crossed the farmyard between the shop and sheep barn. “Would you have time for another small job?” I asked the electrician who came out to raise the wire.

When I told him what I wanted, he looked at me as if I might be a little off in the head, but graciously installed the switch anyway.

That night, for probably the first time in 15 years, darkness fell over the farmyard. And like balm to my soul, darkness, made doubly sweet by silence, fell over me. It was summer, and for the past month, irrigation engines had been thrumming around the clock and from every direction. But it had rained recently, so my father and the surrounding farmers had turned off their pumps.

Now, with the absence of all that manmade noise and light, the night came back to life. Ambient light from a cloud-obscured moon glazed the road between the house and mailbox somewhat, but I couldn’t gauge the distance between my eyes and the ground. This made each step I took an act of faith. Imagining the blackness around me as unfarmed prairie filled me with the sense of limitless possibility I’d last felt as a child when much more of the original grasslands remained. I even felt a little of the fear I’d last experienced in childhood, which was fine by me. With the fear came a heightened sense of being alive.

“The strangest thing,” said my aunt as I sauntered across the farmyard the next morning, my spirits high. “Did you notice that the yard light went out last night?”

I told her that I’d turned it off and that I hoped to keep it off from now on. I asked her, “Won’t it be nice to step outside at night whenever you want to and see the stars?”

She stared at me as if I’d lapsed into a foreign language. “Well don’t leave it off again,” she finally said. “That light’s for see-cure-i-ty.” She drew the word out the way she used to do when my cousins and I were children and she wanted to explain something to us.

It would take more words than I had available to me that morning to explain to her why that light, like the constant noise of irrigation engines, had the opposite effect of instilling security in me. Both absences, of silence and of darkness, were a deep disturbance of the natural world I’d grown up taking for granted. I needed the place I was from to be the same place, so that I could be the person the place had made.

May 21, 2020

Our Turn at This Earth: Could This Be Why We Are Here?

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs weekly on High Plains Public Radio.

Black Hole

I don’t think I could have been any older than ten. I remember I was crossing our farmyard, in shorts, my legs, bare above my cowboy boots, slicing forward in a purposeful gait. Perhaps I was headed to the barn corral to catch one of my horses.

Given the nature of the thought that was about to stop me in my tracks, I must have been mulling over the notion of infinity, a concept my father had introduced me to when we stood at night out by the yard fence, gazing at the stars. He said the stars went on forever in all directions. “How is that possible?” I often wondered. But what else could the stars do? If they stopped what would be beyond them? Nothing? What was nothing? It must have been at about that juncture in my usual state of perplexity when the new question brought me to a halt: How could there be anything at all?

There must have been nothing at some point, back before the universe began. So how could anything come out of nothing? Even if God created the universe, as I was taught in Sunday School, who, or what, created God? I remember standing there in the broad, stark light of a Kansas summer afternoon, my mind reeling with the strangeness of existence. “How did I get here? How did anything get here?”

I was not an unusually precocious child. I was just doing what humans do, wondering why things are the way they are. Our intellectual curiosity distinguishes us from the other beings on this planet. Perhaps most animals are curious. Just think of the dog who must explore every corner of a house or yard. But as far as we know, dogs don’t ponder the stars or the origins of the universe. Our tendency to ask big questions seems embedded in our DNA.

“To what end?” I wonder. It is comforting to think there might be a reason we evolved with the marvelous capacity, not only to ask but to answer big questions. Take for instance one recent discovery. How thrilled my father would have been to open his newspaper, as I did one morning last spring, and see a picture astronomers had taken of red and fiery yellow light surrounding a dark disk of concentrated matter about to be sucked into a black hole in the constellation Virgo.

Our curiosity also leads us inward, to discover that our own bodies contain a veritable universe of microbes without which we could not function. The latest estimate is 100 trillion microbial cells within us versus just 10 trillion human cells. Such knowledge heightens our awareness of the interconnectedness of all life and leads me to wonder if the universe itself is a giant organism in which we humans are a tiny, but integral, part.

A little child perches on a farmyard fence, the toes of her cowboy boots wedged in the wire, beside a father pointing toward the Milky Way, explaining that the stars go on forever. What if that father and child are fulfilling their intended role in the maturation of the universe they ponder? What if their wondering and the wondering of the billions of other humans like them is the universe’s only means of knowing itself?

If we humans understood how interconnected we are with everything that is, if we had this view of ourselves as an integral part of a whole, would we be more respectful of the whole? As it is, we seem engaged in a race between two sides of our natures – our quest for knowledge on the one hand and on the other our greed to have all we desire regardless of how much damage we do to the web of life. Our curiosity can lead to ever greater understanding of what we and the universe really are, while our greed threatens our very survival. What a pity, what a phenomenal loss, it will be if greed wins.