Julene Bair's Blog, page 6

March 16, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: A Plains State Without Indians

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/05541_regional_OTE-A-Plains-state-without-Indians-airs-031518.mp3

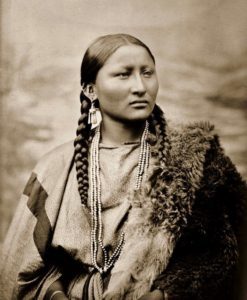

Pretty Nose, a Cheyenne woman. 1878, Fort Keogh, Montana

L. A. HUFFMAN Photo

When we were kids, my brother Bruce had a knack for finding arrowheads on the pasture hills surrounding our family’s farm. Once, he even found a point resting in the grass at the base of a neighbor’s light pole. I would drag sharp edges of flint of chert against my palm and imagine braves racing bareback over our once unfenced pastures. But despite the fact that these artifacts practically littered the ground beneath my feet, I grew up ignorant of Indian history. I didn’t know that many of the battles I’d seen on TV and at the movies, between cowboys, or cavalry, and Indians had taken place right in the Kansas-Colorado border region where we lived.

“A plains state without Indians is a dull blade,” the North Dakota historian, Clay Jenkinson, has written. He describes a sense of compelling edginess in Nebraska and the Dakotas, where there are large reservations. I think I understand what he means. Because no descendents of the people who camped and hunted on the land before we laid claim to it attended my school or lived anywhere nearby, I never had the benefit of their resentment. I say “benefit” because if I’d understood that rights to the land I lived on had been fiercely contested, I could not have helped interrogating my own relationship with it—something I did come to do but at a much later age.

I don’t even remember learning, as a child, that the county I lived in had been named after the commanding general in the Plains Indian Wars. Only as an adult did I read about General William T. Sherman’s “final solution of the Indian problem,” as he called it, which was to kill as many Indians as possible and exile the remainder. He ordered troops to attack villages in winter, so that more men, women, and children could be killed, and to destroy their livestock so that survivors would starve. To the same end, he encouraged the extermination of what remained of the estimated 40 million bison that once roamed the plains.

Being a member of a family that ultimately profited from the questionable and often criminal treatment of the natives doesn’t make me responsible for those practices. My ancestors and others who seized the opportunity for a better future in once-Indian lands can’t be blamed either. Government policies underwrote their entitlement to all that would yield a profit—whether roads or railroads through native hunting grounds, gold, or rich farm land. But I do think that those of us who occupy once Indian lands should at least learn how that land came into our possession. We can acknowledge the often brutal history and we can teach as true and objective a version of it as possible to the younger generations. We can inform ourselves and pray that, through knowledge and the expanded empathy that knowledge brings, we will find the courage to speak up for the rights of the natives who do remain and for the heath of the land itself, so that those who come after us can also call it home.

March 9, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: In Search of Live Water

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/05541_regional_OTE-In-search-of-live-water-airs-030818.mp3

I once read a beautiful definition of a spring: “a place where, without the agency of man, water flows from rock or soil.” That water can just appear in this way, often in a very dry place, has enchanted me ever since I was a young woman, traveling and camping in the Mojave Desert. In those miraculous places where water trickled through cracks in granite or up from an otherwise dry creek bed, life sprang forth as magically as the water. Fish weaved through clear pools, casting shadows on sand or gravel bottoms. Birds darted among willow shrubs and cottonwoods. Bees buzzed. Butterflies flitted from flower to flower. Invariably, I found places in the lush grasses where deer or antelope had slept.

I once read a beautiful definition of a spring: “a place where, without the agency of man, water flows from rock or soil.” That water can just appear in this way, often in a very dry place, has enchanted me ever since I was a young woman, traveling and camping in the Mojave Desert. In those miraculous places where water trickled through cracks in granite or up from an otherwise dry creek bed, life sprang forth as magically as the water. Fish weaved through clear pools, casting shadows on sand or gravel bottoms. Birds darted among willow shrubs and cottonwoods. Bees buzzed. Butterflies flitted from flower to flower. Invariably, I found places in the lush grasses where deer or antelope had slept.

Many years later, memories of those lush desert springs inspired me to search for places where water still flowed from rock or soil on the High Plains. I had read that groundwater pumping from the Ogallala Aquifer was causing the water table to drop below the level of the streambeds and drying out the historic springs where Indians had camped and pioneers had first settled. This concerned me personally because I was destined to inherit part of our family farm. Like thousands of other farms on the High Plains, ours withdrew hundreds of millions of gallons from the aquifer each year.

Exploring the mostly farmed countryside was not as exciting as exploring wild desert mountains. But spotting a pond reflecting blue sky in the distance, pulling onto the side of a gravel road, and hiking over pasture hills to sit beside live water, as the pioneers had called the water in springs, delighted me even more than discovering springs in the Mojave had. More, because the discovery meant that at least my family and other irrigation farmers had not, as yet, robbed the surface of every last drop.

But the surface is definitely being de-watered on the High Plains, and the situation worsens with each passing year. The loss of springs dries up spring-fed creeks and plains rivers, all of which, with the exception of the Platte, the Arkansas, and the main fork of the Canadian, are fed by the Ogallala. The North Fork of the Canadian, in the Texas Panhandle, the Smoky Hill in western Kansas, and the Republican, which flows from Colorado into Nebraska and Kansas, are vanishing. According to a Colorado State University study, the area where those three states come together lost 350 miles of streams between 1950 and 2010.

The life that thrives in and beside live water dies when the water does. Trees lose their leaves and their trunks and branches turn gray. Grasses shrivel. Birds disappear. There is no more shade, no more fish, no more habitat for wildlife in general. News stories about the dwindling Ogallala Aquifer emphasize the economic suffering to come. There is no doubt those consequences will be dire. But to me, losing, due to the agency of man, those places where once, without the agency of man, water flowed from rock or soil is the most tragic loss of all.

March 7, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth – Big Daddy

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/05541_regional_OTE-Big-Daddy-airs-030118.mp3

When I farmed with my father in the mid-1980s, I often expressed my concern that the water we were withdrawing from the Ogallala Aquifer, to irrigate our crops, would one day run out. My father, who was one of those hardy old-timers—a grandson of pioneers—said, “Don’t worry. Big Daddy will put the plug in before it’s too late.” By “Big Daddy,” he meant the government.

When I farmed with my father in the mid-1980s, I often expressed my concern that the water we were withdrawing from the Ogallala Aquifer, to irrigate our crops, would one day run out. My father, who was one of those hardy old-timers—a grandson of pioneers—said, “Don’t worry. Big Daddy will put the plug in before it’s too late.” By “Big Daddy,” he meant the government.

“Until then, I got mine!” He said this to get a rise out of me, and it always worked. In truth, though, he didn’t want to see the water disappear any more than I did. But like any businessman, he didn’t see it as his job to regulate himself. He intended to continue profiting from business as usual, until the government stepped in to save the aquifer. He had every reason to trust that this was inevitable, since, over his lifetime, he’d seen many environmental protections put in place.

As a young man, he’d seen FDR swoop in to save the Plains from another Dust Bowl. In order to qualify for federal Farm Program payments, he had to terrace his hillier land to prevent erosion. Under President Nixon, he’d seen the Environmental Protection Agency established and legislation passed protecting the nation’s air and water. Recently, in another effort to conserve topsoil, the government had begun requiring that he leave more organic matter on the surface between harvests.

But my father was wrong. Big Daddy never did step in. Today, farmers still receive Farm Program assistance to grow water-intensive crops such as corn and soybeans regardless of whether they farm in wet or dry climates. In 2005, the federal government also created the Renewable Fuel Standard, which requires that more and more ethanol be added to gasoline each year, thereby incentivizing farmers to grow more and more corn, the main feedstock for ethanol. These measures, combined with some severe drought years, have caused aquifer levels to drop twice as fast over the last six years than they did in the previous sixty.

I knew my father pretty well. He certainly would have enjoyed the boom in corn prices that resulted from the ethanol mandate. But he also would have readily admitted that yes, it is too bad—downright sad, really—to see farmers’ wells running dry and all of the streams, ponds, and reservoirs where he used to fish, and even swim as a child, drying up. He wasn’t one to “make a fuss.” He didn’t like to “stick his nose in” or his “neck out.” While he never wrote or called a politician to lobby for more subsidies, he certainly wouldn’t have written or called to ask for fewer of them or for changes in policy to preserve the aquifer.

Many argue that preserving the aquifer should be left up to those who draw their livelihoods from it. But business people cannot be expected to curtail their own immediate profits. Saving the aquifer will depend on others who have a stake in a livable future on the High Plains to stick their noses in, their necks out, and speak up.

March 2, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Writing on the Wall

“Our Turn at this Earth” is broadcast Thursdays at 6:44 pm on HPPR radio.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/05541_regional_OTE-Writing-on-the-wall-airs-022218.mp3

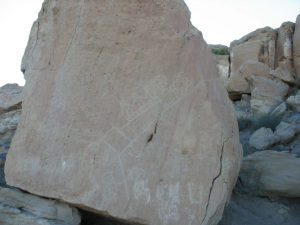

Prophecy Rock – Susan O’Shea Photo

According to legends passed down from generation to generation among the Hopi Indians, humanity has occupied three previous worlds, each of which was destroyed because we failed to honor the instructions of our creator. I learned about this myth from a man named James, a Hopi farmer whose family I stayed with during a 1980s visit to Hotevilla, the most traditional Hopi village.

James explained to me that his people are grateful that in this, the fourth world, they live in a desert. Desert life helps keep the Hopi mindful of their limits and encourages them to stay in balance with nature. The desert, he indicated, is like a strict mother who doesn’t let her children step far out of line. She provides the necessities, but only if crops are carefully tended and water, the greatest gift of life, is carefully preserved.

Lest the Hopi forget this basic fact of desert life, they have prophecy rock—a sandstone boulder into which their ancestors carved two horizontal, parallel lines. On the upper line stand four human stick figures who, according to James’s interpretation, indicate the way of the white man, who values material goods over a simple life in keeping with nature. To the right of the final figure, the line zigzags off into space.

On the far end of the lower line is another stick figure, this one tending corn, as the Hopi had done for over a thousand years. This line does not break off but continues on around the edge of the rock. James and the other elders in Hotevilla could read the writing on the wall. They tried to teach the young people in the village to stay on this more righteous path.

My people take pride in our rationality. We do not make decisions based on ancient prophesies, but on observable facts—hard data gathered scientifically. But today science has given us our own writing on the wall, and it is telling us the same thing the Hopi’s prophecy tells them—that if we continue upsetting the balance of nature, we will come to ruin. On the High Plains, where, for decades, farmers have been withdrawing much more water from the Ogallala Aquifer than what returns to it through natural recharge, charts generated by land grant university scientists and the U. S. Geological Survey tell us that the water will soon be gone. The measures being taken in response to these reliable prophesies that meet even our exacting standards for truth are minor. They may slow the depletion of the aquifer, but not by much.

It seems strange, does it not, that we know more about nature than any society ever has, yet we choose to ignore that knowledge, thus endangering our own and all of nature’s future? Unlike the Hopi, our living in a very dry place did not humble us or encourage us to stay within our natural limits. For that, we would have needed a spiritual tradition that recognizes our kinship with all of nature, of which we are only a small part.

February 24, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: As If No Tomorrow

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs every Thursday at 6:44 pm CT on KANZ.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/05541_regional_OTE-As-if-no-tomorrow-airs-021518.mp3

Hopi Farmer in his Bean Field, with Corn Behind

When, as a young woman, I had the good fortune to stay for a few days in the home of a Hopi farming family, I saw many similarities between my host, James, and my own father. Both men had spent virtually every day of their lives outdoors, tilling soil and caring for crops. And they both did this in a dry place—in James’s case the northern Arizona desert, and in my father’s, the high, dry plains of western Kansas. Although my father farmed with big machines and James still planted by hand, they were both proficient dry-land farmers, meaning they had to be expert at nurturing the moisture in their soil.

James’s dry-land methods involved planting his corn, beans, and squash far apart and channeling rainwater alongside his crops. My father’s methods involved fallowing his wheat ground every other year and keeping as much organic matter on the surface as possible while also preventing weeds from sapping the moisture that accumulated during the fallow periods. When planting, he carefully adjusted his machines’ depth, placing seeds just deep enough to tap into the subsurface moisture. But that began to change in my late teen years, when my father drilled his first high-capacity well into the Ogallala Aquifer. He didn’t seem to worry what effect irrigation would have on the aquifer.

James, on the other hand, would never have considered drilling a well to water his crops. He didn’t even have a house well. In fact, I had traveled to the Hopi reservation with a friend who was helping the villagers publicize their objections to the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ intention to drill a well in the village. From the Bureau’s point of view, this would entail much needed modernization, but James and his neighbors were certain that pumping water and storing it in a tower would give them too easy access to water, which would lead to waste, and eventually dry out the spring that trickled from the side of the mesa on which they lived.

It is hard to imagine two more different cultural approaches. The Hopi, having lived in that part of the Arizona desert for over six-hundred years, were so concerned for their future in that place that they were willing to lie down in front of bulldozers to prevent a small municipal well from going in. Meanwhile, my father and other High Plains farmers, whose families had lived in that region for about one-hundred years, were pumping and drilling as if there were no tomorrow, in the process, almost guaranteeing that there would not be.

Ever since my visit to the Hopi Reservation in the early 1980s, I have wondered what accounts for these two cultures’ radically different relationships to the water on which life in their respective dry places depends. What are your thoughts? I invite you to leave a comment on HPPR’s “Our Turn at this Earth” web page, or on my own website. If leaving public comments is not your thing, use the contact form. I’d love to hear from you!

February 15, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: A Deeply Rooted Way of Life

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs every Thursday at 6:44 pm CT on KANZ.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/05541_regional_A-deeply-rooted-way-of-life-airs-020818.mp3

When I was a young woman, a friend who assisted the Hopi Indians with their causes invited me to join him on a visit to Hotevilla, the most traditional village on the Hopi Indian reservation. The Hopi descended from ancient Pueblo cultures that emerged in the desert Southwest around the 12th Century BC. They dwell in the region we now think of as northern Arizona. Their ability to stay in one place through the seasons, decades, and centuries rests on the domestication of corn on this continent seven thousand years ago.

When I was a young woman, a friend who assisted the Hopi Indians with their causes invited me to join him on a visit to Hotevilla, the most traditional village on the Hopi Indian reservation. The Hopi descended from ancient Pueblo cultures that emerged in the desert Southwest around the 12th Century BC. They dwell in the region we now think of as northern Arizona. Their ability to stay in one place through the seasons, decades, and centuries rests on the domestication of corn on this continent seven thousand years ago.

As we approached across the desert floor, I at first mistook the low-lying, flat-roofed stone houses for rock formations atop the mesa on which they stood. But soon we were inside one of those “formations,” made warm by a fire in an iron stove, sharing supper by kerosene lantern light with a family whose members sometimes lapsed into a native tongue that predated English on this continent by thousands of years.

As someone who had always taken pride in having descended from pioneers, it humbled me to realize that my people were actually newcomers in the Western Hemisphere. But it also felt affirming to once again be in the quiet, grounded presence of a farm family. Sitting at table with them, eating a meal of chicken stew and blue-corn piki bread made entirely from homegrown ingredients, had an elemental, earth-bound wholesomeness about it that reminded me of my own farm childhood.

The next day, we went with our host, James, to the plot of land he farmed and watched as he planted corn, by hand, in mounds a few feet apart. While his subsistence farming differed dramatically from the production agriculture my Kansas family practiced, the visit nevertheless felt like a return—not to my direct personal past, but to an ancient way of life in which all modern farming is rooted.

I paid that visit to Hotevilla during my desert-traveling years, and much as the desert had immersed me in the qualities of aridity that had formed my spirit as a child—reliable sunlight, blue skies, distances, pale vegetation, clarity of light and air—so this visit with a desert family awakened me to my own farm family’s heritage in a deep and universal way of life that drew both sustenance and meaning from the soil.

As archetypal examples of farming people, the Hopi provided a mirror in which I began to examine my own family’s farming practices. A sense of longevity emanated from their way of life, their houses, and from them. I imagined how comforting it would be knowing that your people’s tenure in one beautiful place went back a thousand years and was viable enough to go on for a thousand more. The Hopi, for me, embodied the most essential lesson to be taken from living off the land as farmers do. You do not use a place up and move on. That would negate the whole cultural benefit of agriculture, which first made settlement, and civilization, possible.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/05541_regional_A-deeply-rooted-way-of-life-airs-020818.mp3

February 5, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Full Speed Ahead

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs every Thursday at 6:44 pm CT on KANZ.

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/05541_regional_Full-speed-ahead-airs-020118.mp3

In the mid-1980s my father got a letter from the Kansas Water Office warning that, from then on, farmers who didn’t report their annual water use would be fined. This was long before our Groundwater Management District began requiring meters on irrigation wells, so we would have to extrapolate the amount of water we’d pumped that year from utility bills for the natural gas that powered our five well engines.

In the mid-1980s my father got a letter from the Kansas Water Office warning that, from then on, farmers who didn’t report their annual water use would be fined. This was long before our Groundwater Management District began requiring meters on irrigation wells, so we would have to extrapolate the amount of water we’d pumped that year from utility bills for the natural gas that powered our five well engines.

This was going to be complicated, to say the least. Complaining that he couldn’t get his “old noggin” to do the math, Dad assigned me the task. As with all of the farm-related jobs he gave me, I felt honored that he would entrust this one to me. But I was not prepared for the results of my calculations, and once they were in hand, I wished I’d never been asked to perform them. Despite having worked in the farm all summer—helping lay eight-inch diameter pipe across the tops of our fields, changing sets each morning and night, and personally witnessing the water coursing down each furrow—the quantity of water we were using didn’t hit home until I pushed the sum button on my mother’s electric calculator. 1-3-9-,-0-0-0-, 0-0-0? I checked my math again and again.

Filing our farm’s water reports fell to me every year after that, right up until we sold our farm in 2006. Some years we used as “little” as 139 million gallons, but in other years we used over two and half times that amount. We had a permit from the Kansas Water Office to pump 1400 acre feet of water, or enough water to bury 1400 acres a foot deep. A football field without end zones is about an acre. Imagine glass walls rising above that field a quarter mile into the sky, water poring over the brim.

When you take into consideration that ours was just one middling to large farm among 32,000 irrigated farms in the Ogallala Aquifer region, then it should be no great surprise that the water reserves under the High Plains are rapidly diminishing. Hydrologists estimate that the aquifer refills, under irrigated land in western Kansas, at the rate of 1.1 to 1.8 inches per year. Our water permit allowed us to pump 17.5 inches onto 960 irrigated acres. That means we had permission to take water out at about ten times the rate of optimum recharge.

On the day I ran the numbers for our first water report, the pride I took in my heritage as a High Plains farmer began to morph into a sense of complicity. Ever since the technology had arrived on the scene for irrigation development in the region, it had been full speed ahead, and now I was one of the farmers with a foot on the pedal. The direction we seemed to be heading was not into greater and greater prosperity, as most irrigation farmers and the communities that depended on the revenue the water generated seemed to believe, but toward a brick wall.

January 25, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: The Water that Could Last Forever

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs every Thursday at 6:44 pm CT on KANZ.

Our Turn at this Earth: Homecoming

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs every Thursday at 6:44 pm CT on KANZ (High Plains Public Radio).

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/05541_regional_Homecoming-airs-011818.mp3

In the mid-1980s, when I returned to western Kansas after a sixteen year absence, I was shocked by the changes irrigation had brought to our once dry-land wheat farm. Many of the wheat fields and pastures of my childhood had been replaced by irrigated corn. The water that made this more lucrative, but very thirsty, crop possible came from the vast Ogallala Aquifer, which underlies western Kansas and portions of seven other states.

In the mid-1980s, when I returned to western Kansas after a sixteen year absence, I was shocked by the changes irrigation had brought to our once dry-land wheat farm. Many of the wheat fields and pastures of my childhood had been replaced by irrigated corn. The water that made this more lucrative, but very thirsty, crop possible came from the vast Ogallala Aquifer, which underlies western Kansas and portions of seven other states.

We hadn’t begun using the center pivot sprinklers that rotate through circles of corn, soybeans and cotton on the High Plains today. We still flooded our fields out of eight-inch, gated pipes. As my father’s “floodman,” it was my job to go out to the fields each morning and evening and change the irrigation sets. When I opened the gates in the pipe, the water would gush out in beautiful arcs that I loved to slice my hand through. But I had come back to Kansas after living in the Mojave Desert, and living in the desert had sensitized me to the value of water. I couldn’t send that precious Ogallala water coursing down the furrows without feeling that I was participating in the demise of an aquifer that no one, including my own family and plains ancestors, could have survived there without.

I understood why my father and his neighbors had seized upon this new technology. With it they could water their fields at the touch of a switch on an irrigation engine, whereas before, they had been solely reliant on the whims of weather. But I couldn’t understand how they could watch water pour out of those pipes and not worry that the aquifer would dry out eventually. Scientists had been issuing warning to this effect since 1901, when Willard D. Johnson, a government geologist sent to survey the High Plains, reported that, quote, “the withdrawal of an amount sufficient for irrigation would rapidly result in exhaustion of the stored supply.”

Today many farmers have run out of water. If withdrawals continue at current rates, most others will run out by the middle of this century. News reports quote some farmers as saying that when their parents or grandparents first tapped into the aquifer for irrigation, they thought that the water would last forever. If so, those irrigation pioneers did not avail themselves of the evidence that Johnson and virtually every geologist and hydrologist who came after him provided.

As children of the semi-arid plains, they must have known in their bones that any story of water that could last forever was a fairytale. But when it is expedient to do so, we humans have this tendency to ignore science and our own bone-deep knowledge. Eventually, and inevitably, problems that go unaddressed become too big to ignore. Our choice at that point is to throw up our hands and resign ourselves to the loss or finally, and at long last, resolve the problem. I hope that farmers and other plains citizens will choose resolve rather than resignation and save what remains of the Ogallala Aquifer before it is too late.

January 11, 2018

Our Turn at this Earth: Cheater Bars and Self-Reliance

“Our Turn at this Earth” airs every Thursday at 6:44 pm CT on KANZ (High Plains Public Radio).

http://www.julenebair.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/05541_regional_Cheater-bars-and-self-reliance-airs-011118.mp3

Photo by Joe Angell

As a young girl, I resented the gender divisions on my family’s Kansas farm, where my brothers worked in the barn and fields and I was relegated to cooking, gardening and cleaning the house with my mom. Today I realize that all of our work contributed equally to our thriving in that place, but I grew up in a cultural climate that viewed women incapable of fixing a tractor, while to cook or sew threatened a man’s masculinity.

I therefore considered it quite a triumph when, in my early thirties, I learned the basics of engine mechanics. This knowledge proved necessary because I had become obsessed with the rugged beauty of the Mojave Desert and often traveled there alone. A breakdown in the middle-of-nowhere types of places I loved most could prove disastrous.

A cheerful and supportive guy friend of mine helped me overcome my misgivings by sharing with me four basic premises that farm boys understand before they learn their ABCs. (1) Throw yourself into the work, and don’t worry about getting your hands dirty. Grease can be cleaned off. In fact, they sell this stuff in an orange bottle made expressly for that purpose. (2) Don’t worry about not being strong enough. Anyone can loosen a stubborn bolt with a “cheater’s bar,” which is nothing other than a length of pipe that you can fit over the end of a wrench. (3) Don’t worry about lacking knowhow. You can buy a manual for virtually any vehicle that will walk you through repairs step-by-step. If you’re still baffled, do what guys do. Go back to the auto supply store, plunk your greasy water pump or whatever down on the counter, and ask the parts guy what to do next.

These lessons acted like a cheater bar themselves, breaking free in my mind the stubborn notion that there were certain types of work that only a guy could do. My newfound confidence emboldened me to act on my wildest dream. In my desert travels I had run across a beautiful but abandoned rock cabin that sat on a hillside surrounded by over a million mountainous acres of dramatic desert. With the permission of the ranching couple who owned the cabin, I moved there and over the coming months made it habitable.

My biggest challenge came when the 1959 Ford pickup that I needed to haul equipment and lumber for those repairs spun a rod bearing. During a visit, the mechanic guru who’d taught me those basics helped me pull the engine, but I disassembled it myself and took the crankshaft to a machine shop to be reground. To this day, I recall the sense of fulfillment I felt after I put the engine back together, and it fired up! Driving with one hand, my elbow resting on the sill and smiling, I reminded myself of my father as he drove through his fields.

Back in my cabin, I would sit down to the dinner I cooked, happy to realize at last that there was no such thing as men’s work or women’s work. There was just work. It felt good to have crossed the divide.