Bacil Donovan Warren's Blog, page 16

August 10, 2015

I was your medic

I was your medic

—Bacil Donovan Warren

You might remember me, although I don't remember you,

It's nothing personal, you see—I very seldom do.

I treat a lot of people, and I see more every day;

Now, if the call was really bad, the memory might stay.

Especially if it involved a child—maybe yours?—

Whose face was blue, head slumping down, as we came through the doors.

You held her precious body out for us to lend a hand

"You must save her!" you screamed at us, as we calmly began.

Or was it from this call we ran, a couple months ago;

A flare up at a barbecue; a man who did not know

The gas had already been on, and tried to light the flame,

What I recall most about it: him, screaming out in pain.

As many of my colleagues know, I joke about our work,

None of it is intended to be rude; I'm not a jerk.

It's simply how many of us deal with the deathly ill,

The ugly truth about it, is that many haunt me still.

The agony in faces wracked with fear about the fate

Of a father, or a friend, who seems at Heaven's gate;

A tearful wail as medics fail to work their magic touch—

Sometimes, when I remember them, it really is too much.

And so I work to bury it, so deep inside my soul.

I let it out in little bursts as jokes—that is my role.

But many nights I lie in bed, because I cannot sleep;

The memories of those I've lost—into my brain they creep.

They torture me with thoughts about the things I did, or not;

Was there more I could have done? Just give me another shot!

The second, or the third or fourth, a chance to do again

And step back into history—remembering only then

That nothing that I do or say has made them come alive

I couldn't make it better then, and they did not survive.

So as I lay with the demon Doubt twisting in my head,

I circle into bitter thoughts, just laying in my bed.

One month turns to five or six, Doubt eating me from within

My coping mechanisms can no longer calm the din.

The demon leads me to the gun, I keep for safety's sake;

Ironic how I use it now, the cycle for to break.

I didn't think that anyone would get just how I feel;

I thought I would get laughed about—the medic who can't deal!

It tears my soul apart now when I dwell upon this pain,

I just wish I could have reached out and didn't have to feign

Being well: a happy face, be that medic you all know

Has it all together!—I tell you now, it's all a show.

If only I had taken time, to talk about these fears

I might not now be looking down, your faces wet with tears.

My memorial is over, my friends have said goodbye,

Some of them are back to work, while others will sit and cry.

I was your medic, at one time, but since I kept it in,

I took my life when demon Doubt no longer stayed within.

I beg you now, my medic friends, don't keep it buried down

Hiding under a false face; the station's duty clown.

Talk to someone who can help you deal with this Doubt.

I do not want another soul to accompany me out.

If you are an EMS provider, and you are feeling haunted & brought to the brink of suicide by those demons of Doubt, or the memories of the ones you couldn't save, you can get help: the Code Green Campaign has a lot of resources you can use to help with those. It sucks when we lose patients, but there is hope. You are not alone.

—Bacil Donovan Warren

You might remember me, although I don't remember you,

It's nothing personal, you see—I very seldom do.

I treat a lot of people, and I see more every day;

Now, if the call was really bad, the memory might stay.

Especially if it involved a child—maybe yours?—

Whose face was blue, head slumping down, as we came through the doors.

You held her precious body out for us to lend a hand

"You must save her!" you screamed at us, as we calmly began.

Or was it from this call we ran, a couple months ago;

A flare up at a barbecue; a man who did not know

The gas had already been on, and tried to light the flame,

What I recall most about it: him, screaming out in pain.

As many of my colleagues know, I joke about our work,

None of it is intended to be rude; I'm not a jerk.

It's simply how many of us deal with the deathly ill,

The ugly truth about it, is that many haunt me still.

The agony in faces wracked with fear about the fate

Of a father, or a friend, who seems at Heaven's gate;

A tearful wail as medics fail to work their magic touch—

Sometimes, when I remember them, it really is too much.

And so I work to bury it, so deep inside my soul.

I let it out in little bursts as jokes—that is my role.

But many nights I lie in bed, because I cannot sleep;

The memories of those I've lost—into my brain they creep.

They torture me with thoughts about the things I did, or not;

Was there more I could have done? Just give me another shot!

The second, or the third or fourth, a chance to do again

And step back into history—remembering only then

That nothing that I do or say has made them come alive

I couldn't make it better then, and they did not survive.

So as I lay with the demon Doubt twisting in my head,

I circle into bitter thoughts, just laying in my bed.

One month turns to five or six, Doubt eating me from within

My coping mechanisms can no longer calm the din.

The demon leads me to the gun, I keep for safety's sake;

Ironic how I use it now, the cycle for to break.

I didn't think that anyone would get just how I feel;

I thought I would get laughed about—the medic who can't deal!

It tears my soul apart now when I dwell upon this pain,

I just wish I could have reached out and didn't have to feign

Being well: a happy face, be that medic you all know

Has it all together!—I tell you now, it's all a show.

If only I had taken time, to talk about these fears

I might not now be looking down, your faces wet with tears.

My memorial is over, my friends have said goodbye,

Some of them are back to work, while others will sit and cry.

I was your medic, at one time, but since I kept it in,

I took my life when demon Doubt no longer stayed within.

I beg you now, my medic friends, don't keep it buried down

Hiding under a false face; the station's duty clown.

Talk to someone who can help you deal with this Doubt.

I do not want another soul to accompany me out.

If you are an EMS provider, and you are feeling haunted & brought to the brink of suicide by those demons of Doubt, or the memories of the ones you couldn't save, you can get help: the Code Green Campaign has a lot of resources you can use to help with those. It sucks when we lose patients, but there is hope. You are not alone.

Published on August 10, 2015 11:56

February 25, 2015

Final delivery (Desert Sabre recollections, final part)

The night of the 26th gave way to the morning of the 27th, and we had made our big right turn and were headed straight into the northern edge of the Iraqi positions. Just a bit to the south of us, 1st Armored Division was fighting a major engagement with the Medina Luminous division (Medina Ridge), while we were plowing through a couple of Iraqi divisions and—along with the 24th Infantry Division, to our north—closing the Iraqi escape routes to the the river valley.

Sometime after about 1400 local time on the 27th, we had moved into blocking positions and received orders to halt and consolidate our positions and forces. Our platoon sergeant, SFC Young, set a sleep plan, and I was fortunate enough to be selected to be the first on our tank to get to sleep. I grabbed my nomex jacket as a pillow, jumped out on the back deck of the tank, and it took about two seconds to fall into a deep slumber …

… so deep, that the next thing I knew I was being jostled awake rudely by my gunner, SGT Planter, who was kicking me as hard as he could on the bottoms of my boots, and screaming "GET THE FUCK UP GET THE FUCK UP" as loud as he could muster at me. At first, I didn't understand what was going on. Why am I being screamed at and why is he kicking me? I thought to myself, as I slowly realized that he wasn't the loudest thing going on at that moment. He was screaming because the sound of the Iraqi artillery falling all around our position hadn't woken me up, and it was the most noise he could make at me without actually hitting me in the head with the butt of an M-16 rifle.

When the realization hit me about what was going on, I scrambled to my knees, grabbed hold of the rear of the bustle rack of the turret, and hoisted myself onto the turret roof, just in time to hear the explosion of a round landing a few dozen meters away (and see SGT Planter disappear inside the turret through my loader's hatch). I fell inside the hatch, closed it up, looked at SGT Planter and mouthed "thanks." The whole troop was scrambling to back down into hide positions, while the squadron command net was blistering with reports of artillery fire and orders to displace.

In the turret, SGT Planter properly took up scanning his firing arc, watching in case the arty barrage was a precursor to a counter-attack by Iraqi forces. I spun my loader's hatch periscope toward the left rear of the turret, maintaining what air observation I could, as the LT was guiding SPC Thomas backward down the hill we were hidden behind. After a bit, we were down far enough that we couldn't see over the top of the ridgeline any more—in tank parlance, we were in a "hide" position, where none of the turret was exposed to the front, and the enemy—and the LT ordered SPC Thomas to give a hard right backward to turn around. SGT Planter kept the gun tube pointed toward the enemy, as I felt the jerking on the controls and the acceleration as Errol whipped our tank around at high speed. Oriented with the tank facing west, and the turret facing east, we high-tailed to the new assembly area and awaited additional orders. During our evac, I asked SGT Planter how long I had been sleeping, and he thought for a moment and said "just a couple of minutes."

It felt like hours. Truly, I felt invigorated. Partly that was the epinephrine coursing through my arteries after having been 1) rudely awakened from what was likely a near-immediate drop from wakefulness into delta sleep; and 2) feeling like I was only a little bit better aim—or worse timing—from being permanently attached to the land in Iraq, courtesy of an Iraqi artillery round. Partly, though, even a couple of minutes of sleep seemed to rejuvenate me, and I was much more alert.

After an electric few minutes waiting for the Iraqi counter-attack to materialize over the ridgeline, the squadron command net chirped to life with a new FRAGO, and the LT started mapping our new objective. There was some back-and-forth with the various commanders, including our Troop commander, and a new destination and mission were assigned. 3d ACR, as well as 24th Infantry Division, were establishing blocking positions to prevent the Republican Guard from simply retreating back across the Euphrates river, maybe about a hundred kilometers west of Az Zubayr and just south of the marshland on the south bank of the river valley. We had accomplished all of our objectives to this point, and were given some follow-on missions to support the efforts of VII Corps, to our south, in rendering the Republican Guard incapable of continued operations.

One of these missions was to move a few klicks to the east, to set up a blocking position on the right flank of the 24th, and the left flank of VII Corps, and establish essentially a screen line†. We ferried the LT to a meeting at the Troop TOC, where the updated orders were given and some additional information was disseminated. Of that, there were some "Lessons Learned" already available from the VII Corps' actions at both Medina Ridge, and the battle of 73 Easting. One of those, and the one I think that was the least surprising yet most assuring, was that of all the advantages our tanks had perhaps the most glaring was our ability to use the thermal imaging system to acquire and engage enemy targets at ranges well beyond that at which the Iraqi tanks could effectively fire. This by itself was a tremendous advantage, but also had been drilled into our heads from the very beginning (not only of Desert Shield, but in general). He who sees the enemy first shoots first, and shooting first equals killing first. Our tanks were, in some cases, able to acquire enemy tanks at 3000+ meters, and able to engage and destroy them on the first shot at ranges well over 2500+ meters with something like 90% first-shot hits. The sabot round of the 120mm M1A1 was easily able to penetrate frontal turret and hull armor of the Iraqi tanks at those ranges, and was achieving catastrophic kills of those targets with those long-range, first-shot hits. Additionally, we learned that several M1 tanks had taken direct hits from enemy tanks, some at very, very close range (less than 400 meters, in at least one case) with no friendly casualties from it.

There had been some issues with friendly fire, and we were warned to try harder to positively identify vehicles before firing on them. The Iraqis were not without some positives; their defense against the attack of the 1st Armored at Medina Ridge was shown as an effective method for them. They had arrayed a defense using a technique called a 'reverse slope' defense, where instead of being at or in front of the ridgeline, able to look across a long expanse of terrain, they were behind it, prepared to engage units as they crested the ridgeline. It didn't help much; the 1st Armored still didn't have any tank casualties due to enemy fire, but the rest of the US Army was given the heads-up about this action as a planning tool to enable us to anticipate and react to known enemy tactics.

After retrieving the LT and resuming our role on the screen line, there were some preparations. First, we were ordered to prepare in-place for what could be described as our "anvil" role; that is, if the VII Corps advance continued, we'd be the Anvil to their Hammer: they would drive the enemy toward us, and we'd be sitting in prepared positions to destroy the enemy with long-range firepower as the VII Corps continued to push them. Engineers came and prepared hasty defensive positions, and we set up a sleep and guard plan for the second time. This time, I volunteered for first guard duty. I was assigned to a walking patrol, given a radio and night vision goggles and my driver Errol was assigned to patrol with me while one of the other tanks put a watch in their TC's .50 cal spot. We did our patrols, were relieved at the appropriate time, and finally got a chance to sleep.

This time, we did sleep. Several hours worth, in fact. We were roused about 04:50 or so (28 FEB), and had a few minutes to tidy up and get ourselves into our highest state of readiness and alertness. After so doing, we took a few moments to finish up some basic maintenance tasks, walking track and checking various bolts for tightness, looking at our fuel and other consumable levels (hub lubrication and shock absorbers, for example), and so forth. We had an MRE breakfast, and while we were consuming it, another FRAGO came over the squadron command net: at 07:45 local time there would commence a large-scale artillery barrage, which would continue for about 16 minutes; then, at 08:01 local time, there would be a unilateral cease fire in place. We were stunned, frankly. I think we were all pretty much in disbelief about the message, and so nothing really changed for us, at that time.

Right on cue, at 07:45 local time, we could hear artillery and rocket fire commence. All of it seemed to be outbound; we never heard or saw anything coming back in our direction. At 08:01, silence.

Silence.

After about a quarter of a minute mostly spent craning our necks, as if incredulous at the lack of sounds of military activity, a great WHOOP! was let out by one or other of our nearby troop mates, and we gave a little prayer and celebrated: we did it! We lived, we were going to make it home.

After a few moments of celebrating, our platoon sergeant refocused us on our other tasks: continuing maintenance, making sure guard rotations were still in effect, resuming our tanker duties. After what seemed like only a few minutes, but was in reality I think about an hour or an hour and a half, the radio sparked to life again: another FRAGO. One of the problems with cutting off an enemy unit completely from their communications is that, in case there is a cease-fire, not all units may be aware of it, and continue to act as if the conflict is still in full effect. It's a common problem in warfare, and has happened numerous times throughout history, where a combatant unaware of the cessation of hostilities will engage an enemy, and the battle continues for a short time. Well, for us, that's what happened.

Just a little bit after the cease-fire kicked in, there had apparently been an aircraft shot down not too far away from our location; there was a rescue mission launched, and the medevac chopper sent to retrieve the pilot had also been shot down. The chopper was about ten or so klicks from our location, just to the west of Ar Rumaylah airfield. We were ordered to secure the crash site, destroy any enemy air defense in the area, and secure the airfield.

We mustered, received some additional information from the command net, and then began our assault eastward yet again. As we approached the crash site (which was to the north of my tank by a kilometer or so, in the Eagle troop 2/3 ACR sector), we started to encounter some bunker complexes and had to take up immediate RPG guard position; now, in addition to scanning the rear air for enemy aircraft, I also had to keep an eye out on the ground for RPG teams that might pop up from behind us, and take them out before they could fire on our tanks. I was eagle-eyed, maintaining a constant focus on every dip, bunker, or small rock where an enemy infantryman might try to cause my tank crew harm, but fortunately these were all empty. As we approached the ridgeline ahead, the scout platoon radioed contact with enemy forces, dug in tanks and PCs with anti-aircraft vehicles. The troop commander ordered tanks front, and we pulled through in a line formation to a position in turret defilade where we could see the airfield and their defending tanks. We were waiting for confirmation from the Squadron commander to engage, and SGT Planter was acquiring targets in his firing sector. Eagle Troop to our north was also preparing for a hasty attack. Finally, the Squadron commander gave the go-ahead, and the Troop commander issued his Troop fire command, and we began engaging targets.

With many of the tanks oriented toward Eagle Troop, we had clear shots at the air defense vehicles and BMPs that were arrayed on the southern end of the airfield. "GUNNER HEAT AA" started the fire command from the LT.

"IDENTIFIED" replied SGT Planter.

"UP!" I yelled, signifying that the HEAT round in the main gun breech was loaded and the gun was armed.

"FIRE AND ADJUST" ordered the LT.

"ON THE WAY!" SGT Planter's first shot at a Roland AA missile system was prematurely detonated by an unseen fence between us and it; his second shot destroyed the Roland system utterly.

I loaded a third HEAT round, yelled "UP!" into the intercom, and waited for SGT Planter to identify his next target; a BMP. Downrange the round went, followed by a shout of "TARGET" by SGT Planter indicating the BMP was hit, and the clanking of the aft cap on the turret floor as I slammed another HEAT round into the main gun. "UP!"

After what must have been a minute or two, we were ordered to continue to advance on the airfield, secure it, and await additional orders. We complied, and as we were approaching the burnt-out hulks of vehicles just on the outskirts of the airfield defenses, the scout platoon warned of a minefield at the airfield's edge. They marked the edges of it as best they could, and we bypassed to the south of the airfield. Engineers would come in after us, and take care of that little problem, so we continued our eastward advance.

As we were bypassing the mines, another FRAGO came: we were to advance to an OBJECTIVE to our east, where a dug-in enemy position had been seen by air crews, and secure it. Scouts front in a Vee formation, tank platoons behind in a line, we continued attacking eastward through undulating sand and rock terrain.

T-72 in the "crater" formations we discovered"RED 1, RED 3: CONTACT FRONT TANKS AND PCs OUT!" came from the lead scout vehicle; and the battle drill began. The scout CFVs were using their 25mm cannons to engage BMPs, while we were racing forward to find and destroy enemy tanks. The scout platoon leader reported to the Troop commander, while the Troop XO was relaying to the Squadron commander on the Squadron command net. As we approached the burning hulk of a BMP earlier destroyed by the scouts, we stopped for a moment to assess what had happened. In so doing, the LT and I popped out of our hatches, and realized that we were hip-deep into an enemy encampment, which the scouts had bypassed so quickly they didn't realize they had done so. The unit was a tank battalion of the Tawakalna Republican Guard division, and there were T-72s, BRDMs, trucks, jeeps, and portable trailers in what looked like simple craters dug out of the ground; from ground level more than a few meters away, they were invisible.

T-72 in the "crater" formations we discovered"RED 1, RED 3: CONTACT FRONT TANKS AND PCs OUT!" came from the lead scout vehicle; and the battle drill began. The scout CFVs were using their 25mm cannons to engage BMPs, while we were racing forward to find and destroy enemy tanks. The scout platoon leader reported to the Troop commander, while the Troop XO was relaying to the Squadron commander on the Squadron command net. As we approached the burning hulk of a BMP earlier destroyed by the scouts, we stopped for a moment to assess what had happened. In so doing, the LT and I popped out of our hatches, and realized that we were hip-deep into an enemy encampment, which the scouts had bypassed so quickly they didn't realize they had done so. The unit was a tank battalion of the Tawakalna Republican Guard division, and there were T-72s, BRDMs, trucks, jeeps, and portable trailers in what looked like simple craters dug out of the ground; from ground level more than a few meters away, they were invisible.

The LT reported to both the scout platoon leader, and to the Troop commander, his findings and assessment of the situation: we need to clear these features before moving forward. While waiting for the scouts to return, we were attacked by what appeared to be a single rifleman with his AK-47; I first engaged with my loader's M240 machine gun, and then the LT had SGT Planter turn the coax M240 on him.

The next few hours was spent guarding this location, as the intel guys came through; it turned out to be a pretty high-level headquarters for the Republican Guard unit, and included the capture of a battalion commander-equivalent CO of the Iraqi army, and a trailer full of encryption equipment, plans, maps, and so forth.

After we were cleared of the site, and pulled through to temporary positions about six kilometers east, we were ordered to halt and establish defensive positions overlooking a local road system (which, as it turns out, was Highway 8 and Freeway 1). We could overlook the highways from a commanding position, and stayed in this position for several more days. During that time, the 24th Infantry Division to our north reporting being fired upon from the highway, and engaged enemy units there; we were ordered to stay in a position to counter-attack if the 24th got into a protracted fight but never did get involved in that particular action.

Disabled Iraqi artillery piece, just left of "^ C6", which

Disabled Iraqi artillery piece, just left of "^ C6", which

was later used as a gunnery practice targetOver the next several days, we performed our normal maintenance duties, did guard patrols, did some gunnery practice, and finally got a chance to eat some hot food. Mail arrived, some of it more than a week old already, and we relished the opportunity to reconnect our brains with the thoughts of our loved ones, and being able to actually see them again, someday. It didn't take long; our heavy equipment was secured and transported in mid-March, and we flew out of the sandbox late on the 16th of March, 1991, arriving in El Paso on the morning of 18 March, 1991.

I believe we delivered our message, emphatically: if you don't leave Kuwait, we will destroy your military. There are questions about the long-term effect of Desert Storm, and some who believe that we didn't go far enough—that we should have turned left, and headed straight to Baghdad—but I'm satisfied with the mission we executed. I'll leave political questions like that to pundits and analysts, at least for now.

†: Screen line: a position for recon units, where they spread out in what amounts to a fairly thin line of observation posts, in an effort to visualize as much geography as possible. The purpose of said line is to be a screen on the flank, front, or rear of a larger force, to provide warning and initial attrition of enemy units before they are able to reach the main body of that larger unit.

Some of 2nd Platoon, C Troop, 1/3 ACR

Some of 2nd Platoon, C Troop, 1/3 ACR

displaying a captured Iraqi Tanker's

helmet after our attack through the Republican

Guard.

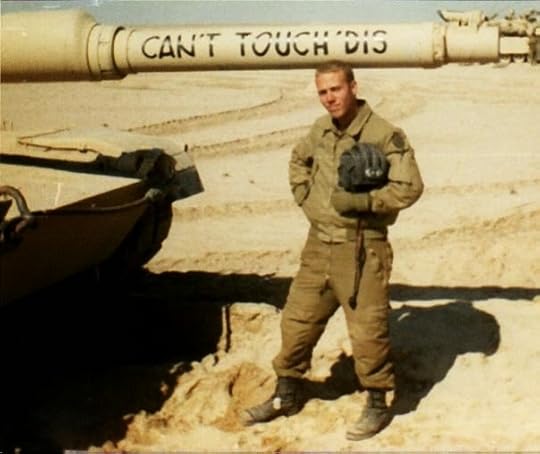

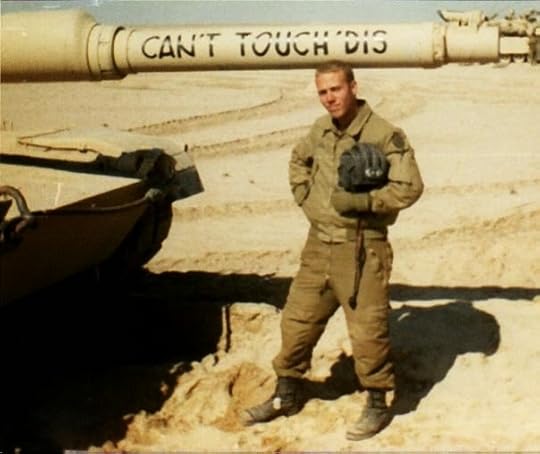

The author, posing with the same helmet

The author, posing with the same helmet

as in the previous picture.

Sometime after about 1400 local time on the 27th, we had moved into blocking positions and received orders to halt and consolidate our positions and forces. Our platoon sergeant, SFC Young, set a sleep plan, and I was fortunate enough to be selected to be the first on our tank to get to sleep. I grabbed my nomex jacket as a pillow, jumped out on the back deck of the tank, and it took about two seconds to fall into a deep slumber …

… so deep, that the next thing I knew I was being jostled awake rudely by my gunner, SGT Planter, who was kicking me as hard as he could on the bottoms of my boots, and screaming "GET THE FUCK UP GET THE FUCK UP" as loud as he could muster at me. At first, I didn't understand what was going on. Why am I being screamed at and why is he kicking me? I thought to myself, as I slowly realized that he wasn't the loudest thing going on at that moment. He was screaming because the sound of the Iraqi artillery falling all around our position hadn't woken me up, and it was the most noise he could make at me without actually hitting me in the head with the butt of an M-16 rifle.

When the realization hit me about what was going on, I scrambled to my knees, grabbed hold of the rear of the bustle rack of the turret, and hoisted myself onto the turret roof, just in time to hear the explosion of a round landing a few dozen meters away (and see SGT Planter disappear inside the turret through my loader's hatch). I fell inside the hatch, closed it up, looked at SGT Planter and mouthed "thanks." The whole troop was scrambling to back down into hide positions, while the squadron command net was blistering with reports of artillery fire and orders to displace.

In the turret, SGT Planter properly took up scanning his firing arc, watching in case the arty barrage was a precursor to a counter-attack by Iraqi forces. I spun my loader's hatch periscope toward the left rear of the turret, maintaining what air observation I could, as the LT was guiding SPC Thomas backward down the hill we were hidden behind. After a bit, we were down far enough that we couldn't see over the top of the ridgeline any more—in tank parlance, we were in a "hide" position, where none of the turret was exposed to the front, and the enemy—and the LT ordered SPC Thomas to give a hard right backward to turn around. SGT Planter kept the gun tube pointed toward the enemy, as I felt the jerking on the controls and the acceleration as Errol whipped our tank around at high speed. Oriented with the tank facing west, and the turret facing east, we high-tailed to the new assembly area and awaited additional orders. During our evac, I asked SGT Planter how long I had been sleeping, and he thought for a moment and said "just a couple of minutes."

It felt like hours. Truly, I felt invigorated. Partly that was the epinephrine coursing through my arteries after having been 1) rudely awakened from what was likely a near-immediate drop from wakefulness into delta sleep; and 2) feeling like I was only a little bit better aim—or worse timing—from being permanently attached to the land in Iraq, courtesy of an Iraqi artillery round. Partly, though, even a couple of minutes of sleep seemed to rejuvenate me, and I was much more alert.

After an electric few minutes waiting for the Iraqi counter-attack to materialize over the ridgeline, the squadron command net chirped to life with a new FRAGO, and the LT started mapping our new objective. There was some back-and-forth with the various commanders, including our Troop commander, and a new destination and mission were assigned. 3d ACR, as well as 24th Infantry Division, were establishing blocking positions to prevent the Republican Guard from simply retreating back across the Euphrates river, maybe about a hundred kilometers west of Az Zubayr and just south of the marshland on the south bank of the river valley. We had accomplished all of our objectives to this point, and were given some follow-on missions to support the efforts of VII Corps, to our south, in rendering the Republican Guard incapable of continued operations.

One of these missions was to move a few klicks to the east, to set up a blocking position on the right flank of the 24th, and the left flank of VII Corps, and establish essentially a screen line†. We ferried the LT to a meeting at the Troop TOC, where the updated orders were given and some additional information was disseminated. Of that, there were some "Lessons Learned" already available from the VII Corps' actions at both Medina Ridge, and the battle of 73 Easting. One of those, and the one I think that was the least surprising yet most assuring, was that of all the advantages our tanks had perhaps the most glaring was our ability to use the thermal imaging system to acquire and engage enemy targets at ranges well beyond that at which the Iraqi tanks could effectively fire. This by itself was a tremendous advantage, but also had been drilled into our heads from the very beginning (not only of Desert Shield, but in general). He who sees the enemy first shoots first, and shooting first equals killing first. Our tanks were, in some cases, able to acquire enemy tanks at 3000+ meters, and able to engage and destroy them on the first shot at ranges well over 2500+ meters with something like 90% first-shot hits. The sabot round of the 120mm M1A1 was easily able to penetrate frontal turret and hull armor of the Iraqi tanks at those ranges, and was achieving catastrophic kills of those targets with those long-range, first-shot hits. Additionally, we learned that several M1 tanks had taken direct hits from enemy tanks, some at very, very close range (less than 400 meters, in at least one case) with no friendly casualties from it.

There had been some issues with friendly fire, and we were warned to try harder to positively identify vehicles before firing on them. The Iraqis were not without some positives; their defense against the attack of the 1st Armored at Medina Ridge was shown as an effective method for them. They had arrayed a defense using a technique called a 'reverse slope' defense, where instead of being at or in front of the ridgeline, able to look across a long expanse of terrain, they were behind it, prepared to engage units as they crested the ridgeline. It didn't help much; the 1st Armored still didn't have any tank casualties due to enemy fire, but the rest of the US Army was given the heads-up about this action as a planning tool to enable us to anticipate and react to known enemy tactics.

After retrieving the LT and resuming our role on the screen line, there were some preparations. First, we were ordered to prepare in-place for what could be described as our "anvil" role; that is, if the VII Corps advance continued, we'd be the Anvil to their Hammer: they would drive the enemy toward us, and we'd be sitting in prepared positions to destroy the enemy with long-range firepower as the VII Corps continued to push them. Engineers came and prepared hasty defensive positions, and we set up a sleep and guard plan for the second time. This time, I volunteered for first guard duty. I was assigned to a walking patrol, given a radio and night vision goggles and my driver Errol was assigned to patrol with me while one of the other tanks put a watch in their TC's .50 cal spot. We did our patrols, were relieved at the appropriate time, and finally got a chance to sleep.

This time, we did sleep. Several hours worth, in fact. We were roused about 04:50 or so (28 FEB), and had a few minutes to tidy up and get ourselves into our highest state of readiness and alertness. After so doing, we took a few moments to finish up some basic maintenance tasks, walking track and checking various bolts for tightness, looking at our fuel and other consumable levels (hub lubrication and shock absorbers, for example), and so forth. We had an MRE breakfast, and while we were consuming it, another FRAGO came over the squadron command net: at 07:45 local time there would commence a large-scale artillery barrage, which would continue for about 16 minutes; then, at 08:01 local time, there would be a unilateral cease fire in place. We were stunned, frankly. I think we were all pretty much in disbelief about the message, and so nothing really changed for us, at that time.

Right on cue, at 07:45 local time, we could hear artillery and rocket fire commence. All of it seemed to be outbound; we never heard or saw anything coming back in our direction. At 08:01, silence.

Silence.

After about a quarter of a minute mostly spent craning our necks, as if incredulous at the lack of sounds of military activity, a great WHOOP! was let out by one or other of our nearby troop mates, and we gave a little prayer and celebrated: we did it! We lived, we were going to make it home.

After a few moments of celebrating, our platoon sergeant refocused us on our other tasks: continuing maintenance, making sure guard rotations were still in effect, resuming our tanker duties. After what seemed like only a few minutes, but was in reality I think about an hour or an hour and a half, the radio sparked to life again: another FRAGO. One of the problems with cutting off an enemy unit completely from their communications is that, in case there is a cease-fire, not all units may be aware of it, and continue to act as if the conflict is still in full effect. It's a common problem in warfare, and has happened numerous times throughout history, where a combatant unaware of the cessation of hostilities will engage an enemy, and the battle continues for a short time. Well, for us, that's what happened.

Just a little bit after the cease-fire kicked in, there had apparently been an aircraft shot down not too far away from our location; there was a rescue mission launched, and the medevac chopper sent to retrieve the pilot had also been shot down. The chopper was about ten or so klicks from our location, just to the west of Ar Rumaylah airfield. We were ordered to secure the crash site, destroy any enemy air defense in the area, and secure the airfield.

We mustered, received some additional information from the command net, and then began our assault eastward yet again. As we approached the crash site (which was to the north of my tank by a kilometer or so, in the Eagle troop 2/3 ACR sector), we started to encounter some bunker complexes and had to take up immediate RPG guard position; now, in addition to scanning the rear air for enemy aircraft, I also had to keep an eye out on the ground for RPG teams that might pop up from behind us, and take them out before they could fire on our tanks. I was eagle-eyed, maintaining a constant focus on every dip, bunker, or small rock where an enemy infantryman might try to cause my tank crew harm, but fortunately these were all empty. As we approached the ridgeline ahead, the scout platoon radioed contact with enemy forces, dug in tanks and PCs with anti-aircraft vehicles. The troop commander ordered tanks front, and we pulled through in a line formation to a position in turret defilade where we could see the airfield and their defending tanks. We were waiting for confirmation from the Squadron commander to engage, and SGT Planter was acquiring targets in his firing sector. Eagle Troop to our north was also preparing for a hasty attack. Finally, the Squadron commander gave the go-ahead, and the Troop commander issued his Troop fire command, and we began engaging targets.

With many of the tanks oriented toward Eagle Troop, we had clear shots at the air defense vehicles and BMPs that were arrayed on the southern end of the airfield. "GUNNER HEAT AA" started the fire command from the LT.

"IDENTIFIED" replied SGT Planter.

"UP!" I yelled, signifying that the HEAT round in the main gun breech was loaded and the gun was armed.

"FIRE AND ADJUST" ordered the LT.

"ON THE WAY!" SGT Planter's first shot at a Roland AA missile system was prematurely detonated by an unseen fence between us and it; his second shot destroyed the Roland system utterly.

I loaded a third HEAT round, yelled "UP!" into the intercom, and waited for SGT Planter to identify his next target; a BMP. Downrange the round went, followed by a shout of "TARGET" by SGT Planter indicating the BMP was hit, and the clanking of the aft cap on the turret floor as I slammed another HEAT round into the main gun. "UP!"

After what must have been a minute or two, we were ordered to continue to advance on the airfield, secure it, and await additional orders. We complied, and as we were approaching the burnt-out hulks of vehicles just on the outskirts of the airfield defenses, the scout platoon warned of a minefield at the airfield's edge. They marked the edges of it as best they could, and we bypassed to the south of the airfield. Engineers would come in after us, and take care of that little problem, so we continued our eastward advance.

As we were bypassing the mines, another FRAGO came: we were to advance to an OBJECTIVE to our east, where a dug-in enemy position had been seen by air crews, and secure it. Scouts front in a Vee formation, tank platoons behind in a line, we continued attacking eastward through undulating sand and rock terrain.

T-72 in the "crater" formations we discovered"RED 1, RED 3: CONTACT FRONT TANKS AND PCs OUT!" came from the lead scout vehicle; and the battle drill began. The scout CFVs were using their 25mm cannons to engage BMPs, while we were racing forward to find and destroy enemy tanks. The scout platoon leader reported to the Troop commander, while the Troop XO was relaying to the Squadron commander on the Squadron command net. As we approached the burning hulk of a BMP earlier destroyed by the scouts, we stopped for a moment to assess what had happened. In so doing, the LT and I popped out of our hatches, and realized that we were hip-deep into an enemy encampment, which the scouts had bypassed so quickly they didn't realize they had done so. The unit was a tank battalion of the Tawakalna Republican Guard division, and there were T-72s, BRDMs, trucks, jeeps, and portable trailers in what looked like simple craters dug out of the ground; from ground level more than a few meters away, they were invisible.

T-72 in the "crater" formations we discovered"RED 1, RED 3: CONTACT FRONT TANKS AND PCs OUT!" came from the lead scout vehicle; and the battle drill began. The scout CFVs were using their 25mm cannons to engage BMPs, while we were racing forward to find and destroy enemy tanks. The scout platoon leader reported to the Troop commander, while the Troop XO was relaying to the Squadron commander on the Squadron command net. As we approached the burning hulk of a BMP earlier destroyed by the scouts, we stopped for a moment to assess what had happened. In so doing, the LT and I popped out of our hatches, and realized that we were hip-deep into an enemy encampment, which the scouts had bypassed so quickly they didn't realize they had done so. The unit was a tank battalion of the Tawakalna Republican Guard division, and there were T-72s, BRDMs, trucks, jeeps, and portable trailers in what looked like simple craters dug out of the ground; from ground level more than a few meters away, they were invisible.The LT reported to both the scout platoon leader, and to the Troop commander, his findings and assessment of the situation: we need to clear these features before moving forward. While waiting for the scouts to return, we were attacked by what appeared to be a single rifleman with his AK-47; I first engaged with my loader's M240 machine gun, and then the LT had SGT Planter turn the coax M240 on him.

The next few hours was spent guarding this location, as the intel guys came through; it turned out to be a pretty high-level headquarters for the Republican Guard unit, and included the capture of a battalion commander-equivalent CO of the Iraqi army, and a trailer full of encryption equipment, plans, maps, and so forth.

After we were cleared of the site, and pulled through to temporary positions about six kilometers east, we were ordered to halt and establish defensive positions overlooking a local road system (which, as it turns out, was Highway 8 and Freeway 1). We could overlook the highways from a commanding position, and stayed in this position for several more days. During that time, the 24th Infantry Division to our north reporting being fired upon from the highway, and engaged enemy units there; we were ordered to stay in a position to counter-attack if the 24th got into a protracted fight but never did get involved in that particular action.

Disabled Iraqi artillery piece, just left of "^ C6", which

Disabled Iraqi artillery piece, just left of "^ C6", whichwas later used as a gunnery practice targetOver the next several days, we performed our normal maintenance duties, did guard patrols, did some gunnery practice, and finally got a chance to eat some hot food. Mail arrived, some of it more than a week old already, and we relished the opportunity to reconnect our brains with the thoughts of our loved ones, and being able to actually see them again, someday. It didn't take long; our heavy equipment was secured and transported in mid-March, and we flew out of the sandbox late on the 16th of March, 1991, arriving in El Paso on the morning of 18 March, 1991.

I believe we delivered our message, emphatically: if you don't leave Kuwait, we will destroy your military. There are questions about the long-term effect of Desert Storm, and some who believe that we didn't go far enough—that we should have turned left, and headed straight to Baghdad—but I'm satisfied with the mission we executed. I'll leave political questions like that to pundits and analysts, at least for now.

†: Screen line: a position for recon units, where they spread out in what amounts to a fairly thin line of observation posts, in an effort to visualize as much geography as possible. The purpose of said line is to be a screen on the flank, front, or rear of a larger force, to provide warning and initial attrition of enemy units before they are able to reach the main body of that larger unit.

Some of 2nd Platoon, C Troop, 1/3 ACR

Some of 2nd Platoon, C Troop, 1/3 ACRdisplaying a captured Iraqi Tanker's

helmet after our attack through the Republican

Guard.

The author, posing with the same helmet

The author, posing with the same helmetas in the previous picture.

Published on February 25, 2015 10:58

February 23, 2015

A Borderline Crossed, and the delivery of a powerful and urgent message

(Author's note: Many of my recollections about Operation Desert Sabre (originally Desert Sword) are somewhat hazy; much of that because during all of the first 72 hours of the Operation, I didn't get even one second of sleep, and wound up getting all of 5 minutes for the first four days. As a result, the whole thing is somewhat blurry and fused all together.)

After the initial fear and Zen-like focus of crossing into Iraq, the rest of the day of the 24th (24 FEB 1991) generally progressed in a distinctly un-terrifying way: we ran into essentially no resistance, and met all of our objectives without incident. Despite our initial good fortune we were traveling at a good clip, which meant we had to refuel fairly frequently. Refueling in the field is dicey enough, but add the stress of being in an active combat zone (even if we weren't actively being shot at right that moment), and it became downright frightening. Of all the things I did as a tanker, the first refueling operation inside Iraq during the ground war was one of the scariest. Imagine this: you're standing on the back deck of a tank, with a fire extinguisher and an open fueling port, watching to see that the fuel tanks don't become overfilled. First, you're standing on top of the tank. As opposed to, say, being safely ensconced inside the 70 ton (combat loaded, less kits) beast made of rolled homogeneous steel, a secret blend of other armors, and depleted uranium, as any sane person would be. Second, you're in a situation already known to be dangerous enough that US Army protocols dictate a soldier stand right there with one of the tank's portable fire extinguishers in his hands while you're performing it. Third, at any moment, an enemy unit, helicopter (*shudder* perish the thought), or aircraft might get lucky, and catch you with your pants around your ankles refueling, which makes you a fantastic target for being shot. And, as if that weren't enough, fourth (and finally) my eyes, and the eyes of my tank's gunner, SGT Planter, were on the fuel level, not the horizon, meaning our particular tank would be caught wholly unprepared if an enemy were to appear. We were not alone, there was air cover, the 4th Squadron (Long Knife) of the 3d ACR had Kiowa and Apache helicopters nearby, and the rest of our own Squadron and Troop were setting security while refueling operations were in progress. That knowledge does not alleviate the anxiety, just for the record. We would wind up refueling a few more times over the ground war, none of which were quite as tense as the first one.

Looking back toward the Combat Trains of C Troop, 1/3 ACR

Looking back toward the Combat Trains of C Troop, 1/3 ACR

As we continued on, day drifted into night as a blanket of dark dropped over the featureless and empty desert. Navigating in this terrain is next to impossible during the day, but at night it becomes truly impossible … unless you have GPS, which was brand-new then. So brand new, in fact, that we had exactly 2 GPS receivers in the Troop, one with the CO in C-66—the Troop command tank—and one with the XO with the combat trains†. They would communicate occasionally over the Troop's logistical radio freq, to ensure they stayed on course (and to avoid communicating over the combat/command net, which was kept mostly radio "quiet" for combat communications). As the tank's loader, it is my responsibility to keep air guard, when I'm not actively loading the main gun or performing other duties inside the turret, so I kept my focus—and machine gun—pointed toward the rear-left of the tank. I didn't see much of the desert in front of us, but I got good looks at the things we passed. With the onset of evening, I retrieved the night vision goggles, and kept them around my neck for easy retrieval if necessary. The Troop stopped just long enough for the vehicle's drivers to insert their own night-vision equipment, and then we resumed our march. That first night brought the first problem: during our march, we came across some elevated road surfaces that bypassed an unseen feature of the terrain (and, to this day, I still have no idea what it was). The driver of our scout platoon leader's Bradley CFV misjudged the edge of the roadway, and his Bradley rolled over the edge of the embankment injuring the platoon leader and one of the other scouts in the vehicle. We stopped long enough to recover the vehicle, medevac the wounded, and then continued on.

Destroyed enemy vehicles as we pass them, northbound

Destroyed enemy vehicles as we pass them, northbound

Dawn the second day (25 FEB) came, and we started to run into pockets of enemy resistance. Occasional firefights would break out, and since C Troop was (along with B Troop) the front edge of the Regiment's right flank, we caught a lot of these as we swept north toward the Euphrates valley. Mostly, what would happen is that one or other scout platoon would observe enemy defensive positions, the tank platoons would come up and exchange a volley or two of fire with them, and they'd surrender. Sometimes, the enemy troops would surrender when the Bradleys came into view. We began routing hundreds and hundreds of POWs back through the MPs, and continued our advance. The closer we got to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the more frequently we would encounter enemy resistance. This continued unabated for all of the second day, night, and third day (26 FEB).

Starting on the night of the 26th, things became much more … interesting, let's say … and after two days and nights of unbroken advance across a trackless, formless desert, we paused: for an attack on a small town, occupied by a built-up tank and mechanized force of 2nd-tier Iraqi troops (that is, not the Republican Guard—we were still quite a ways from them—but the topmost tier of the regular Iraqi army). We got a radioed FRAGO, halted in place, and set security while Regiment initiated an artillery and rocket barrage on the town's defenders. After about an hour and a half of arty, we executed a hasty attack on the edge of the town. Several firefights broke out, and a few Iraqi tanks were destroyed, but after a few minutes these soldiers surrendered just like all the others had.

During all of our operations, we continued to have basic, normal human needs: eating, drinking, using the latrine. We had a vast stock of MREs on each tank, so food was never an issue. We also had a vast stock of water, believe it or not; each tank went into combat with (IIRC) four cases of 1L bottles of water, plus each of us had two full 2L desert-issue canteens inside the tank, and drank from them frequently (the bottled water, mostly, went into refilling the 2L canteens when they became empty). Many of us—this loader, in particular—also had a crippling addiction to caffeine, and since we weren't stopping hardly at all, it became more and more difficult to make coffee when blood levels became too low for sustained wakefulness. I had caffeine pills (Vivarin® was a favorite), but I preferred to save them for the utmost end of need. Instead, I took to essentially eating the instant coffee packets from the MREs. Only two of us on my tank, SGT Planter and myself, really drank coffee anyway, so it was easy to score the packets from both SPC Thomas and the LT. I'd take two of them and a sugar packet, rip them all open together, and dump their contents into my mouth. One swig of water later, and it was done. It's not the tastiest way to ingest caffeine, but the mother of invention being what she was …

(to be continued …)

†: CO = Commanding Officer, XO = Executive Officer (the 2nd in command of a given unit). Combat Trains refers to the ancillary vehicles of the unit, such as supply, medical, maintenance, etc. These vehicles generally run a few hundred meters behind the "line" vehicles (the tanks and scout Bradleys, in our case), to keep them out of immediate danger, but close enough to provide support to the combat vehicles, if needed. FRAGO = FRAGment Order (that is, not a complete order); a FRAGO is used to signal a unit they have been assigned some task that is different from what their existing orders tell them to do. In this case, we had existing orders to drive north to the river valley with all due speed, and to destroy or render ineffective any enemy units we encountered along the way. Since there was a built-up enemy position discovered, we needed more time and deliberate effort to attack their position, so our orders were temporarily overridden by a FRAGO for the hasty attack.

After the initial fear and Zen-like focus of crossing into Iraq, the rest of the day of the 24th (24 FEB 1991) generally progressed in a distinctly un-terrifying way: we ran into essentially no resistance, and met all of our objectives without incident. Despite our initial good fortune we were traveling at a good clip, which meant we had to refuel fairly frequently. Refueling in the field is dicey enough, but add the stress of being in an active combat zone (even if we weren't actively being shot at right that moment), and it became downright frightening. Of all the things I did as a tanker, the first refueling operation inside Iraq during the ground war was one of the scariest. Imagine this: you're standing on the back deck of a tank, with a fire extinguisher and an open fueling port, watching to see that the fuel tanks don't become overfilled. First, you're standing on top of the tank. As opposed to, say, being safely ensconced inside the 70 ton (combat loaded, less kits) beast made of rolled homogeneous steel, a secret blend of other armors, and depleted uranium, as any sane person would be. Second, you're in a situation already known to be dangerous enough that US Army protocols dictate a soldier stand right there with one of the tank's portable fire extinguishers in his hands while you're performing it. Third, at any moment, an enemy unit, helicopter (*shudder* perish the thought), or aircraft might get lucky, and catch you with your pants around your ankles refueling, which makes you a fantastic target for being shot. And, as if that weren't enough, fourth (and finally) my eyes, and the eyes of my tank's gunner, SGT Planter, were on the fuel level, not the horizon, meaning our particular tank would be caught wholly unprepared if an enemy were to appear. We were not alone, there was air cover, the 4th Squadron (Long Knife) of the 3d ACR had Kiowa and Apache helicopters nearby, and the rest of our own Squadron and Troop were setting security while refueling operations were in progress. That knowledge does not alleviate the anxiety, just for the record. We would wind up refueling a few more times over the ground war, none of which were quite as tense as the first one.

Looking back toward the Combat Trains of C Troop, 1/3 ACR

Looking back toward the Combat Trains of C Troop, 1/3 ACRAs we continued on, day drifted into night as a blanket of dark dropped over the featureless and empty desert. Navigating in this terrain is next to impossible during the day, but at night it becomes truly impossible … unless you have GPS, which was brand-new then. So brand new, in fact, that we had exactly 2 GPS receivers in the Troop, one with the CO in C-66—the Troop command tank—and one with the XO with the combat trains†. They would communicate occasionally over the Troop's logistical radio freq, to ensure they stayed on course (and to avoid communicating over the combat/command net, which was kept mostly radio "quiet" for combat communications). As the tank's loader, it is my responsibility to keep air guard, when I'm not actively loading the main gun or performing other duties inside the turret, so I kept my focus—and machine gun—pointed toward the rear-left of the tank. I didn't see much of the desert in front of us, but I got good looks at the things we passed. With the onset of evening, I retrieved the night vision goggles, and kept them around my neck for easy retrieval if necessary. The Troop stopped just long enough for the vehicle's drivers to insert their own night-vision equipment, and then we resumed our march. That first night brought the first problem: during our march, we came across some elevated road surfaces that bypassed an unseen feature of the terrain (and, to this day, I still have no idea what it was). The driver of our scout platoon leader's Bradley CFV misjudged the edge of the roadway, and his Bradley rolled over the edge of the embankment injuring the platoon leader and one of the other scouts in the vehicle. We stopped long enough to recover the vehicle, medevac the wounded, and then continued on.

Destroyed enemy vehicles as we pass them, northbound

Destroyed enemy vehicles as we pass them, northboundDawn the second day (25 FEB) came, and we started to run into pockets of enemy resistance. Occasional firefights would break out, and since C Troop was (along with B Troop) the front edge of the Regiment's right flank, we caught a lot of these as we swept north toward the Euphrates valley. Mostly, what would happen is that one or other scout platoon would observe enemy defensive positions, the tank platoons would come up and exchange a volley or two of fire with them, and they'd surrender. Sometimes, the enemy troops would surrender when the Bradleys came into view. We began routing hundreds and hundreds of POWs back through the MPs, and continued our advance. The closer we got to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the more frequently we would encounter enemy resistance. This continued unabated for all of the second day, night, and third day (26 FEB).

Starting on the night of the 26th, things became much more … interesting, let's say … and after two days and nights of unbroken advance across a trackless, formless desert, we paused: for an attack on a small town, occupied by a built-up tank and mechanized force of 2nd-tier Iraqi troops (that is, not the Republican Guard—we were still quite a ways from them—but the topmost tier of the regular Iraqi army). We got a radioed FRAGO, halted in place, and set security while Regiment initiated an artillery and rocket barrage on the town's defenders. After about an hour and a half of arty, we executed a hasty attack on the edge of the town. Several firefights broke out, and a few Iraqi tanks were destroyed, but after a few minutes these soldiers surrendered just like all the others had.

During all of our operations, we continued to have basic, normal human needs: eating, drinking, using the latrine. We had a vast stock of MREs on each tank, so food was never an issue. We also had a vast stock of water, believe it or not; each tank went into combat with (IIRC) four cases of 1L bottles of water, plus each of us had two full 2L desert-issue canteens inside the tank, and drank from them frequently (the bottled water, mostly, went into refilling the 2L canteens when they became empty). Many of us—this loader, in particular—also had a crippling addiction to caffeine, and since we weren't stopping hardly at all, it became more and more difficult to make coffee when blood levels became too low for sustained wakefulness. I had caffeine pills (Vivarin® was a favorite), but I preferred to save them for the utmost end of need. Instead, I took to essentially eating the instant coffee packets from the MREs. Only two of us on my tank, SGT Planter and myself, really drank coffee anyway, so it was easy to score the packets from both SPC Thomas and the LT. I'd take two of them and a sugar packet, rip them all open together, and dump their contents into my mouth. One swig of water later, and it was done. It's not the tastiest way to ingest caffeine, but the mother of invention being what she was …

(to be continued …)

†: CO = Commanding Officer, XO = Executive Officer (the 2nd in command of a given unit). Combat Trains refers to the ancillary vehicles of the unit, such as supply, medical, maintenance, etc. These vehicles generally run a few hundred meters behind the "line" vehicles (the tanks and scout Bradleys, in our case), to keep them out of immediate danger, but close enough to provide support to the combat vehicles, if needed. FRAGO = FRAGment Order (that is, not a complete order); a FRAGO is used to signal a unit they have been assigned some task that is different from what their existing orders tell them to do. In this case, we had existing orders to drive north to the river valley with all due speed, and to destroy or render ineffective any enemy units we encountered along the way. Since there was a built-up enemy position discovered, we needed more time and deliberate effort to attack their position, so our orders were temporarily overridden by a FRAGO for the hasty attack.

Published on February 23, 2015 20:06

February 16, 2015

Sci-Fi short story teaser

“Alright, good. Because we can’t take this to the Space Command guys without verifying it.” Steve turned his attention back to the computer screen. “Really, MARVIN? A robot probe with a small wormhole generator? I suppose those magnetic bottle arrays are …” his voice trailed again as the implications swam through his brain. “… Sonofabitch Lance. Write that script and verify. I think MARVIN’s really onto something.”“Workin’ on it now; what do you suppose is up?”“You remember all those magnetic bottles we found, the ones that were almost all intact and still charged?”“Yeah, so?”“They’re photon holders. It’s a quantum signaling system, tied to the generator that MARVIN detected. It all makes sense now.”The stunned silence emanating from the tall, dark-complected Lance seemed almost to vibrate, but his face drained of energy. “So, it’s autonomous, and has a small wormhole generator that can be remotely triggered. You’re saying that it can be operated remotely, instantly, by whomever created it, and it’s deep under the Earth, right now?”

“Well, yeah, I think I am. At least, I think I think.” Steve sighed, stared through the floor, and contemplated his options. “Run your script, dude, and let’s see what comes up.”

“Well, yeah, I think I am. At least, I think I think.” Steve sighed, stared through the floor, and contemplated his options. “Run your script, dude, and let’s see what comes up.”

Published on February 16, 2015 23:18