P.J. Thorndyke's Blog, page 7

June 12, 2015

A Quick Guide to Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper – the personification of shadowy evil in Victorian London and gruesome murder done in gloomy, gaslit streets – has become so entwined in popular culture, appearing in movies, graphic novels and video games, that there are many today who are unaware that he was in fact a real serial killer and not a fictional product of writers. But real he was and perhaps his morbid appeal over a hundred years since his killings has something to do with the fact that he was never caught and never unmasked to spill his secrets. He remains so mysterious and chilling because we have absolutely no idea who he was or why he killed.

Jack the Ripper – the personification of shadowy evil in Victorian London and gruesome murder done in gloomy, gaslit streets – has become so entwined in popular culture, appearing in movies, graphic novels and video games, that there are many today who are unaware that he was in fact a real serial killer and not a fictional product of writers. But real he was and perhaps his morbid appeal over a hundred years since his killings has something to do with the fact that he was never caught and never unmasked to spill his secrets. He remains so mysterious and chilling because we have absolutely no idea who he was or why he killed.

Annie Chapman – The second of the ‘canonical five’ victims

The Whitechapel district of Victorian London was one of the worst slums in Europe. Murder was nothing uncommon in those dim alleys but in the late summer of 1888 a series of killings connected by a modus operandi drew the attention of the police and the press. On 31st of August the body of prostitute Mary Ann Nichols was found in Buck’s Row, a backstreet in Whitechapel. Her throat had been slit twice and her abdomen cut deeply. Some newspapers concluded that a brutal gang was terrorising the working girls of Whitechapel as the body of another prostitute named Martha Tabram had been found stabbed thirty-nine times that same month and yet another prostitute died after being assaulted and robbed by a gang back in April. But on 8th of September another murder took place that suggested that something much more sinister was going on in Whitechapel.

‘The Nemesis of Neglect’ – Punch cartoon by John Tenniel, 1888.

The body of Annie Chapman was found in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, her throat slit and her intestines pulled out. Part of her uterus was also missing. The nation sat up and took note. It appeared that a single man was committing the most gruesome crimes with no motive but to sate his own blood lust. Theories ran wild. Perhaps he was a deranged doctor as the removal of organs hinted at surgical knowledge. Perhaps a butcher or a tanner? Suspects were arrested andreleased without sufficient evidence. An angry mob attacked the Commercial Road police station. A Whitechapel ‘vigilance committee’ was set up which offered a reward for the apprehension of the killer. There were attacks on Jewish businesses as the killer was rumored to be a Jew fulfilling some arcane ritual. In short, fear led to madness.

A further layer of mystery was added to the case by the receival of a letter by the Central News Agency allegedly penned by the killer. Written in red ink and addressed ‘Dear Boss’, the letter boasts of the killings, taunts the police and claims that “The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you.” It was signed ‘Jack the Ripper’. On 30th of September two more prostitutes were slain. Elizabeth Stride was found in Dutfield’s Yard with her throat slashed but was otherwise unmutilated. Later, that same night, the body of Catherine Eddowes was found in Mitre Square, throat slashed, face mutilated, intestines pulled out and kidney and uterus missing. Had the killer been interrupted during his murder of Stride and, thus unsatisfied, gone in search of another victim? An exciting clue was found several streets away in the form of a bloodstained piece of Eddowes’s apron discarded beneath a chalk graffito at the entrance to the Wentworth building (a predominantly Jewish tenement) that read; “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.” Coincidence, or a message from the killer? This mis-spelt scrawling with its double-negative has been a source of much debate and it’s very meaning is hard to discern. It’s generally seen as a proclamation that the Jewish population of Whitechapel refuse to take any responsibility. The work of an anti-Semite with an axe to grind? Or done by the hand of a Jew who grows tired of blame being laid at his door? If so, then why the bloody rag? The decision of Police Superintendent Thomas Arnold and Commissioner Warren to wash the graffito off before it could be photographed for fear that it may spark yet more anti-semitic feelings and the poor transcribing of the words (resulting in differing versions) mean that this particular mystery is unlikely to ever be solved.

Alarmingly within 24 hours of the killings (before the papers revealed them to the public) another letter from ‘Jack the Ripper’ was received by Scotland Yard. A postcard this time, the double-event is referred to and that there had not been time for him to get the ears as she ‘screamed a bit’ (although part of Eddowes’s ear had been detached by the killer’s facial mutilations). The writer also refers to himself as ‘Saucy Jacky’. The knowledge of the murder details before they were made public may make the letters appear genuine but journalists and locals knew these details more or less immediately and the letters are generally dismissed as a hoax or a publicity stunt by the press. One further letter however, was much more macabre as it enclosed a box containing part of a human kidney preserved in ethanol. Addressed ‘From hell’ the letter was clearly done by a different hand than the previous correspondence and was sent to George Lusk, head of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. It read; “Mr Lusk Sor I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer. signed Catch me when you Can Mishter Lusk“. There is still debate over whether this or any of the letters are genuine.

The killer’s most gruesome act was yet to come. On 9th of November the hideously mutilated body of prostitute Mary Jane Kelly was found in her single room at Miller’s Court. Within the privacy of a house it seems, the killer had ample time to go to work. Kelly had been killed by a slash to the throat. Her face was mutilated beyond recognition. Her breasts had been cut off. Her abdomen cut open and her organs scattered around the room and her thighs cut down to the bone. And then, the killings appear to have stopped. There was a murder of a Whitechapel prostitute in July 1889 but that is generally regarded as a copycat killing due to a different implement and less ferocity used in the attack. As for the real ‘Jack the Ripper’, he seems to have vanished without a trace. So what happened? He may have died or been incarcerated for some other offence. The increasing brutality of his crimes point to a mind that was becoming more and more demented so perhaps he was placed in a mental asylum by concerned family members or he may have been one of many mentally ill drifters and vagrants the police had incarcerated in places like Colney Hatch Mental Asylum, forgotten while his crimes went on to spark theories and debate for the next hundred years.

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale

One of the more outlandish theories was outlined in Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution by Stephen Knight and published in 1976. The basic idea is that Queen Victoria’s grandson – Prince Albert Victor – had an affair with a lower class Catholic girl called Annie Elizabeth Crook whom he secretly married. The witness at the wedding was Crook’s friend Mary Jane Kelly. When the Queen and Prime Minister found out about the secret marriage (and resulting child) they ordered Annie placed under the care of Sir William Gull (the Queen’s physician) who certified her insane. The child remained in the care of Mary Jane Kelly whose friends – Mary Ann Nichols, Elizabeth Stride and Annie Chapman – got the idea to blackmail the Royal Family. William Gull and his coachman John Netley thus butchered the girls according to Masonic rituals as part of a coverup by the Freemasons. Catherine Eddowes’s killing was a case of mistaken identity. Despite being largely discredited due to inaccuracies, hoaxes and downright wrong information, variations on the Royal Family/Freemasons/William Gull theory have remained a fascinating idea ever since and form the basis for several fictional accounts such as the BBC’s Jack the Ripper (1988) and the From Hell graphic novel and 2001 film adaptation.

A more compelling theory is presented by true crime writer Martin Fido in his book The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper (1987). In it he claims that the killer was in fact known to the police and was even in their custody at one time! Memoirs and notes of high-ranking police officers at the time including ex-Superintendent Donald S. Swanson reveal the suspect to be a Polish Jew called Kosminski who was brought to a seaside home to be identified by a witness. Although identifying Kosminsky, the witness refused to give evidence as he was a fellow Jew and the police were forced to let Kosminski go, although they kept a close eye on him. Kosminski, a violent woman-hater, was soon sent to Colney Hatch Mental Asylum where he died “a short time after”. For a long time the mysterious Kosminski was generally thought to be Aaron Kosminski, a simple-minded but docile Whitechapel hairdresser who was admitted to Colney Hatch in 1891, over a year after the Ripper killings stopped, but didn’t die until 1919. Fido didn’t believe that this was the same Kosminski mentioned by the police and suggests that Kosminski was mistakenly named in Swanson’s notes instead of a Nathan Kaminsky, a Polish bootmaker in Whitechapel who had been treated for syphilis and vanished after 1888. There is no Kaminsky in the Colney Hatch records, but there is a David Cohen who, Fido argues, may have been a ‘John Doe’ type of label for any Jewish man who couldn’t be identified. Cohen was a violent inmate and died in 1889 and is altogether a better fit for the elusive ‘Kosminski’ mentioned by Swanson. Fido’s theory is that the killer was Nathan Kaminsky who was captured, identified and then released only to wind up in Colney Hatch under the placeholder name of David Cohen. Years later, the retired superintendent Donald S. Swanson, mistakenly recalled the killer’s name as ‘Kosminski’ which coincidentally was the surname of a harmless simpleton who also lived in Whitechapel.

A more compelling theory is presented by true crime writer Martin Fido in his book The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper (1987). In it he claims that the killer was in fact known to the police and was even in their custody at one time! Memoirs and notes of high-ranking police officers at the time including ex-Superintendent Donald S. Swanson reveal the suspect to be a Polish Jew called Kosminski who was brought to a seaside home to be identified by a witness. Although identifying Kosminsky, the witness refused to give evidence as he was a fellow Jew and the police were forced to let Kosminski go, although they kept a close eye on him. Kosminski, a violent woman-hater, was soon sent to Colney Hatch Mental Asylum where he died “a short time after”. For a long time the mysterious Kosminski was generally thought to be Aaron Kosminski, a simple-minded but docile Whitechapel hairdresser who was admitted to Colney Hatch in 1891, over a year after the Ripper killings stopped, but didn’t die until 1919. Fido didn’t believe that this was the same Kosminski mentioned by the police and suggests that Kosminski was mistakenly named in Swanson’s notes instead of a Nathan Kaminsky, a Polish bootmaker in Whitechapel who had been treated for syphilis and vanished after 1888. There is no Kaminsky in the Colney Hatch records, but there is a David Cohen who, Fido argues, may have been a ‘John Doe’ type of label for any Jewish man who couldn’t be identified. Cohen was a violent inmate and died in 1889 and is altogether a better fit for the elusive ‘Kosminski’ mentioned by Swanson. Fido’s theory is that the killer was Nathan Kaminsky who was captured, identified and then released only to wind up in Colney Hatch under the placeholder name of David Cohen. Years later, the retired superintendent Donald S. Swanson, mistakenly recalled the killer’s name as ‘Kosminski’ which coincidentally was the surname of a harmless simpleton who also lived in Whitechapel.

Theories and speculation ramble on. Due to the length of time since the events and the poor records we have of all that occurred, it is unlikely that the truth behind the Whitechapel murders will ever be known. Jack the Ripper, whoever he was, is dead and his secrets died with him leaving us with nothing but our imaginations to fill in the gaps. My own novel Onyx City, while far from presenting a serious theory on the killer’s identity, uses the Whitechapel Murders as a backdrop to a steampunk detective story. It is influenced by the notion that the production of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (which was on at the Lyceum Theatre at the time of the killings) was somehow connected to the strange case of Jack the Ripper. For an excellent resource for all things Ripper visit Casebook: Jack the Ripper

June 8, 2015

Vintage Reads #16 – The English Governess at the Siamese Court

The third Lazarus Longman novel – Onyx City – deals primarily with Victorian London but there is a substantial subplot that is set in Siam (or Thailand as it is called today). In the writing of it I pursued firsthand accounts of nineteenth century Siam as well as researching the country’s complex history and religious fluctuations between Hinduism and Buddhism. The journals of Anna Leonowens, published in 1870, tell a story familiar by other names to modern readers. Fictionalised in 1944 by Margaret Landon as the bestselling Anna and the King of Siam, the film version came out in 1946 and the story was adapted by Rodgers and Hammerstein as a Broadway musical in 1951 by the name; The King and I.

The third Lazarus Longman novel – Onyx City – deals primarily with Victorian London but there is a substantial subplot that is set in Siam (or Thailand as it is called today). In the writing of it I pursued firsthand accounts of nineteenth century Siam as well as researching the country’s complex history and religious fluctuations between Hinduism and Buddhism. The journals of Anna Leonowens, published in 1870, tell a story familiar by other names to modern readers. Fictionalised in 1944 by Margaret Landon as the bestselling Anna and the King of Siam, the film version came out in 1946 and the story was adapted by Rodgers and Hammerstein as a Broadway musical in 1951 by the name; The King and I.

Anna Harriett Edwards was born in 1831 in India and showed an aptitude for languages at an early age. After travelling through Egypt and Palestine under the tutelage of a chaplain and his wife, Anna returned to India and married Thomas Leonowens. The pair moved between Australia, Singapore and Malaysia and had four children, the eldest two dying in infancy. Anna was widowed in 1859 and moved to Singapore where she set up a school for British expats. This brought her to the attention of the Siamese Consul who offered her a job opportunity teaching the many wives, concubines and children of King Mongkut of Siam. Anna sent her daughter, Avis, to boarding school in England and took her son, Louis, with her to Bangkok.

King Mongkut and his son and heir Prince Chulalongkorn

Anyone hoping for a romantic adventure as seen in the movies will be in for a disappointment. Anna’s memoirs are more of a look into the customs and history of Siam and its people rather than a day by day account of her personal experiences although there are many amusing anecdotes that tell of her frustration in a court ruled by tradition and oppression. Although free with her criticism of the natives and her despair at their primitive ways, Anna was clearly infatuated with the land and her descriptions of temples, scenery and village life are indispensable to the modern researcher.

Her role at court was somewhat ambiguous and she remains a controversial figure in Thailand to this day. In addition to her duties as governess, Anna was also called upon by the king to translate letters and act as something of a secretary. It is debatable how much of an influence she had on his foreign policy and also on the political reforms of his son and heir which included the abolition of slavery. After King Monkut’s death in 1868, Anna travelled to New York and continued as a teacher and writer. She was a feminist and a suffragist as well as an extensive travel writer. She died in 1915 in Montreal, Canada. There have been many claims of inaccuracies in her descriptions of King Mongkut as well as exaggerations in her writings levelled at her by his descendants.

June 5, 2015

Inventions and Discoveries of the 19th Century #8 – Submarines

The Turtle with pilot Ezra Lee

The concept of an underwater vessel goes way back with even Alexander the Great rumoured to have used some sort of diving bell for reconnaissance missions. Various designs were worked on in the Middle Ages and the Elizabethan era. Most notable is William Bourne’s 1578 design of a wooden vessel covered in leather that could submerge by decreasing its volume via contracting its sides with hand-turned screws.

The military implications of such devices were the focus of a 1776 attempt by American Revolutionists to destroy the British warship HMS Eagle. The Turtle, designed by David Bushnell, had two propellers powered by a foot treadle and was supposed to drill into the hull of an enemy vessel and attach a keg of gunpowder with a clockwork timer. It is not clear exactly why this plan failed. The pilot – Ezra Lee – may not have been able to penetrate the hull of HMS Eagle or perhaps he was unable to hold the craft stable enough to carry out the work, but the bomb was reported to have gone off downriver after being abandoned by the Turtle, giving the British enough of a fright to make them move their ships further away.

It was France that saw a big increase in interest concerning submarines in the early nineteenth century. American inventor, Robert Fulton, designed and built the Nautilus for the French government in 1800. It was based on the Turtle’s system of propulsion with an added mast and sail for use on the surface. While moderately succesful in tests, Fulton’s relationship with the French government was a rocky one and his submarine was never put into use. Frenchman Brutus de Villeroi pursued the idea and developed the Waterbug in 1833; a small vessel propelled by three pairs of duck paddles. He tried to interest the French and Dutch governments but was unsuccessful and it remained a working prototype. More impressive, was Wilhelm Bauer’s Diable Marin/Seeteufel for the Russians which, in honor of Tsar Alexander II’s coronation in 1855, took a small brass band underwater for a quick rendition which could be heard upon the surface.

The H. L. Hunley. A Confederate submarine and the first in history to sink a warship.

The American Civil War saw several more attempts to bring the submarine into the war arena, mostly by private enterprises in the South who wanted to break the Union’s blockade and cash in on the Confederate privateering law. Their earliest was the Pioneer which, in 1862, sunk a barge with a towed torpedo in a test on Lake Pontchartrain. Designed by James McClintock and financed by Horace Lawson Hunley, it was propelled by a two-man propeller shaft. The vessel never saw service as the Union soon captured New Orleans and the Confederates were forced to scuttle it. While the Union did not openly approve of submarines, there is evidence that they secretly pursued the idea. An early effort was the Alligator, designed by the Waterbug’s father Brutus de Villeroi. Technically the first submarine in the U.S. Navy, the Alligator was sunk in a storm in 1863 before seeing any action. Meanwhile, the Rebels were experimenting with different methods of propulsion. Hunley and McClintock’s American Diver (or Pioneer II) first had an electrical motor and then a steam engine but both were unsuccessful and they fell back on the old hand cranked propeller shaft. The American Diver attempted an attack on the Union Blockade at Mobile Bay but the vessel was too slow and later sank in stormy weather. Not to be deterred, Hunley and co. began work on a new vessel which was commandeered by the Confederates. Hunley remained with the project and was killed during one of its tests, ultimately giving his name to the first submarine to sink a warship. Reluctant to fully submerge the H. L. Hunley, the Confederates used the principal of the earlier ‘David’ torpedo boats which floated on the surface and prodded the enemy vessel with a ‘spar-torpedo’ (an explosive charge attached to an iron bar). In 1864 the Hunley sank the USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor. After the Union ship went down, the Hunley inexplicably sank on its way back to port.

Replica of the Ictineo II in Barcelona Harbor.

Methods of propulsion were always a challenge and the first submarine to successfully make a voyage without human power was the French Plongeur in 1863 using compressed air. The Spanish submarine Ictineo II, designed by Narcis Monturiol, was the first combustion powered submarine. Built in 1864, it was improved in 1867 with an air independent engine relying on a chemical reaction of zinc, manganese dioxide and potassium chlorate which powered a steam engine as well as providing oxygen for breathing, thus skirting the need for a snorkel which all submarines up to this point had employed. Inspired by the submarine’s development (particularly in his homeland), Jules Verne wrote his 1870 novel; 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea which has been a radical influence on the public’s perception of early submarines. While Captain Nemo’s high-tech Nautilus (its name borrowed from Robert Fulton’s design) may be a far-fetched slice of steam-age sci-fi, long-range submarines were anything but a pipe dream by this point. 1888 saw the maiden voyage of the French submarine Gymnote. Powered by an electrical battery, the Gymnote had a periscope and side hydroplanes both of which became standard for submarines. The turn of the century saw gasolene and electic engines replaced by diesel engines which propelled subs on the surface and stored generated electricity for submerged propulsion. With more and more nations being turned on to the idea of submarines in their navy, increase in their construction exploded. By the time the U.S. entered the First World War, it had 24 diesel-powered submarines.

Like the airship, the submarine has become an indelible part of Steampunk. Although used in the navies of many countries today, there is something about the dangerous experiments of the nineteenth century that feeds the imagination of Steampunk writers who tap into a world where the ocean was seen as the final unexplored frontier, much like space would be in the latter half of the twentieth century. The likes of Verne’s Nautilus were brass-clad vessels of discovery in a world where the very nature of warfare was changing. The days of heroic charges into enemy ranks were being replaced by wars of subterfuge and espionage, where a surface-going vessel might be destroyed not by enemy guns, but by a submerged powder charge attached to its hull its crew didn’t even know was there. High-tech and ahead of its time, the submarine is a natural staple of the genre and I made some use of its potential myself in Onyx City.

Like the airship, the submarine has become an indelible part of Steampunk. Although used in the navies of many countries today, there is something about the dangerous experiments of the nineteenth century that feeds the imagination of Steampunk writers who tap into a world where the ocean was seen as the final unexplored frontier, much like space would be in the latter half of the twentieth century. The likes of Verne’s Nautilus were brass-clad vessels of discovery in a world where the very nature of warfare was changing. The days of heroic charges into enemy ranks were being replaced by wars of subterfuge and espionage, where a surface-going vessel might be destroyed not by enemy guns, but by a submerged powder charge attached to its hull its crew didn’t even know was there. High-tech and ahead of its time, the submarine is a natural staple of the genre and I made some use of its potential myself in Onyx City.

June 3, 2015

Steampunk Wednesdays #10 – Van Helsing: The London Assignment (2004)

Some time ago I took a look at the 2004 disappointment Van Helsing. Far better is its animated prequel The London Assignment which came out on home video to coincide with the movie’s release.

Some time ago I took a look at the 2004 disappointment Van Helsing. Far better is its animated prequel The London Assignment which came out on home video to coincide with the movie’s release.

If you’ve seen the movie then you may remember its Paris-set opening where Van Helsing battles the Hulk-like Mr. Hyde, wrecking the stained glass window of Notre Dame in the process. This short animation leads up to that encounter and plays on the long established connection between the Jekyll and Hyde story and the murders of Jack the Ripper (utilised in the 1971 Hammer Horror Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde and in my own novel Onyx City). The plot involves a romance between Dr. Jekyll and Queen Victoria. Jekyll tries to keep Victoria young and beautiful by giving her potions made from the souls of young women – which spells bad news for the prostitutes of London’s Whitechapel district.

June 1, 2015

Vintage Reads #15 – The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

This is one of those stories that really doesn’t need an introduction as so many are familiar with the basic premise of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic – so familiar in fact, that ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ has entered the popular lexicon for any person displaying mood swings or dramatic personality shifts.

This is one of those stories that really doesn’t need an introduction as so many are familiar with the basic premise of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic – so familiar in fact, that ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ has entered the popular lexicon for any person displaying mood swings or dramatic personality shifts.

Purportedly written in a matter of days while Stevenson was feverishly ill in Bournemouth, this slim 1886 novella has had a huge effect on the horror genre and gothic literature. It’s the tale of lawyer John Utterson and his increasing concern for the welfare of his friend Dr. Henry Jekyll who has let a dwarfish and hideously ugly little man called Hyde into his close confidence. Hyde appears to be living with Jekyll and has the use of his cheque book; an arrangement made even more alarming by Jekyll’s new will which makes Hyde the sole beneficiary should Jekyll vanish for a period of more than three months. Utterson is convinced that Hyde is blackmailing his friend over some youthful escapade which could prove scandalous but when Hyde is accused of murdering prominent MP Danvers Carew, the situation is revealed to be something much more sinister.

Jekyll and Hyde is a vastly important book of the Victorian era and much has been made of its allegorical content and social commentary. In the days before the psychoanalysis and personality structures of Sigmund Freud, it’s an interesting take on Dissociative Identity Disorder before such a disorder was identified and Hyde perfectly encapsulates Freud’s ‘id'; a selfish inner personality seeking instant gratification. The story is also seen as a critique on Victorian social standards and the repression of innate lusts by outward respectability. Also, Mr. Hyde seems to represent our less-civilised ancestors. He is described as ‘troglodytic’ and ‘ape-like’ suggesting that he is the Neanderthal still present in all of us no matter how civilised we pretend to be.

A double exposure of Richard Mansfield in both of his roles.

The novella was famously adapted for the stage in 1887 by Thomas Russell Sulivan and Richard Mansfield who played both Jekyll and Hyde. Mansfied was an English actor who worked extensively in America and it was in Boston that the play first opened, moving to London’s Lyceum Theater (managed by Bram Stoker) in August of 1888. Mansfield’s performance as Hyde was apparently so shocking that it had ladies fainting in the audience. His transformation was achieved without technical means and relied only on makeup, lighting and facial contortions. The play was so shocking that parallels began to be drawn between Mansfield’s Hyde and the homicidal maniac who was ripping open prostitutes in Whitechapel at the time.

The connection between R. L. Stevenson’s story and Jack the Ripper has been made again and again in popular culture and it’s not hard to see why. The general assumption made about the Whitechapel killer at the time was that he was a respected member of London’s upper class who allowed his evil alter ego to run riot at night. His knowledge of anatomy may very well have meant that he was a doctor with a sick perversion hidden deep down under a layer of respectability. Among accusations that the 1887 play was encouraging violence and corrupting the morals of its audience (the blaming of society’s problems on popular culture being nothing new) there was even an accusation leveled against Mansfield that he himself was the Ripper! This seems to have come from a single audience member who was convinced that nobody could give such a frightening performance and possibly be sane. There is no evidence to suggest that the police ever considered Mansfield a serious suspect but the idea has taken root along with some of the more outlandish Ripper theories.

The Hyde/Ripper connection has continued in popular culture with the Hammer Horror film Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) and Richard Mansfield (played by Armand Assante) appearing the the BBC’s 1988 two-parter entitled Jack the Ripper. I made use of the connection in my own take on the Ripper case in the upcoming Onyx City, the third in the Lazarus Longman Chronicles in which Richard Mansfield plays a significant part.

May 30, 2015

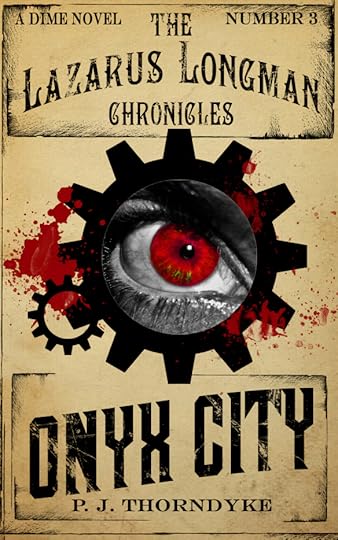

Onyx City – Cover and Blurb

It seems like I barely have any time between the release of one novel before I start promoting the next one, but these three books were written in one go and I don’t see any point in hanging about. That said, this will be the last Lazarus Longman novel for a while. I have plans for a fourth and fifth in the series, but I will be focusing on some other projects for the rest of this year. Anyway, here it is; Onyx City, part detective novel, part political thriller set in the Big Smoke (London) itself.

In two months’ time, Otto Von Bismarck – the Prussian Prime Minister – will arrive in London on a diplomatic visit that could prevent all out war with the German Empire. The city is on tenterhooks. Absolutely nothing must go wrong. That’s why it may be risky to give disgraced agent Lazarus Longman the job of smoothing the way for the dignitary’s visit.

Given a second chance by his superiors, Lazarus reluctantly finds himself in the company of Mr. Clumps – a steam-powered bodyguard – with a mission that plunges him deep into the filthy bowels of the British capital, where danger lurks around every corner. But timing is rarely convenient. A figure from Lazarus’s past has reappeared and a chance to learn the truth about his biological parents is too hard for him to pass up.

And as if the political conspiracies, riots and revolutionist clubs of the Big Smoke weren’t distraction enough, a deranged killer is stalking the gin-soaked slums by night, killing prostitutes and mutilating their corpses. And Lazarus believes that the killings may be connected to his friend; a prominent actor whose erratic behavior and mysterious blackouts could mark him out as a suspect.

May 25, 2015

Vintage Reads #14 – The String of Pearls

The Penny Dreadful was a British kind of Dime Novel that usually dealt with horrific subject matter and didn’t shy away from gore and violence. It’s not known if the term refers to their ‘dreadful’ content or a is comment on the writing quality which could be sketchy to say the least. Nevertheless, these small chapbooks that cost a single penny were a big form of entertainment for the poorer classes in Victorian society.

The Penny Dreadful was a British kind of Dime Novel that usually dealt with horrific subject matter and didn’t shy away from gore and violence. It’s not known if the term refers to their ‘dreadful’ content or a is comment on the writing quality which could be sketchy to say the least. Nevertheless, these small chapbooks that cost a single penny were a big form of entertainment for the poorer classes in Victorian society.

As with the pulp magazines of the twentieth century, many iconic heroes made their debuts in the Penny Dreadfuls like Varney the Vampyre and Spring-heeled Jack. They also fictionalised the exploits of real-life dreadful people such as the highwayman Dick Turpin. But by far the most enduring figure to emerge from the Penny Dreadfuls is Sweeney Todd; the Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

It is unknown if Sweeney Todd existed as an urban legend before the publication of The String of Pearls. We’re not even too sure who wrote it. Serialized in Edward Lloyd’s The People’s Periodical and Family Library in eighteen parts in the winter of 1846/47, the changes in its writing style suggest at least three different authors. In the world of Penny Dreadful publishing, it was not uncommon for the owner of a magazine like Edward Lloyd to buy a cheap story form an unknown author and give it an overhaul via various hack-writers on his staff.

An illustration from a heavily expanded 1850 publication of the novel which was renamed ‘The String of Pearls or The Sailor’s Gift’.

Opening in 1785, the story begins with a sailor and his dog entering the barber shop of Sweeney Todd on Fleet Street. The sailor; Lieutenant Thornhill, recently returned from India, is carrying a message for one Johanna Oakley. The message is accompanied by the titular string of pearls; a gift from Thornhill’s friend Mark Ingestrie, who is presumed lost at sea, to his lover.

I’m sure I’m not giving anything away by revealing the fate of Lieutenant Thornhill upon meeting Sweeney Todd. Anybody who has heard of the Demon Barber will no doubt be familiar with his game; that of murdering the odd customer by the use of a mechanical chair that tips backwards, emptying its occupant through a trapdoor to land on his skull in the cellar below. Todd occasionally has to ‘polish them off’ with his cut-throat razor, and sells their corpses to Mrs. Lovett – owner of the neighboring pie shop – for use in her tasty culinary treats.

When Thornhill doesn’t return from shore leave, his comrade, Colonel Jeffrey, suspects something is amiss; a suspicion hardened by the appearance of Thornhill’s dog who leads Jeffrey to Todd’s shop. Jeffrey falls in with Johanna Oakley and the novel becomes a detective story with many protagonists. As well as Jeffrey and Johanna – the latter of which dresses up as a boy to gain inside knowledge of Todd under the guise of his new apprentice – there’s Tobias Ragg; Todd’s previous apprentice whom he had locked up in an asylum after the lad accuses him of murder. Then there’s Jarvis Williams; a hapless baker conned into making Mrs. Lovett’s meat pies, ignorant of their main ingredient. Lastly, there is Sir Richard Blunt, a magistrate keen on unravelling the mystery and finding the source of the dreadful stink coming from the crypt of St. Dunstan’s Church…

Sweeney Todd became a stock villain in Victorian London’s literary catalogue. He was so popular that he was appearing in stage productions before the concluding installment of The String of Pearls made it to press! His plagiarized story appeared in many more Penny Dreadfuls before the century was out, even making its way to New York in Sweeney Todd or the Ruffian Barber: A Tale of the Terrors of the Seas and The Mysteries of the City. Todd was a villain of pantomime and then cinema, returning to the stage in the Broadway musical that cemented his title as one of pop culture’s major bogeyman.

May 23, 2015

Silver Tomb Released

I’m very happy to reveal that the second Lazarus Longman novel – Silver Tomb – is now available for purchase from Amazon, Amazon UK, Barnes and Noble and Smashwords.

I’m very happy to reveal that the second Lazarus Longman novel – Silver Tomb – is now available for purchase from Amazon, Amazon UK, Barnes and Noble and Smashwords.

His mission was to bring home the wayward fiancé of a British politician who just might be a French spy. But for Lazarus Longman – former explorer and secret agent for the British Empire – things are never that simple. The politician in question was once his friend but is now his bitter rival. The fiancé is France’s leading Egyptologist, a woman whose dealings with a renegade Confederate scientist have drawn the attention of more than the British Secret Service.

From the seedy dens of Cairo’s black market to the backwater villages of the Nile where the burst of Gatling Gun fire is the nationalist war cry, Lazarus finds himself up to his neck in sinister plots, political machinations and the stench of the dead given frightful mobility by modern science. But an unlikely ally blows in on the desert wind – Katarina Mikolavna; an old acquaintance and the Russian Tsar’s deadliest weapon.

Once again the two agents find themselves on opposing sides in a clandestine war of empires that casts its dirigible-shaped shadow over the burning sands of North Africa.

May 21, 2015

A Quick Guide to Mummy Movies

Mummies (of a sort) play a significant role in the second Lazarus Longman novel – Silver Tomb. In writing it I drew on mythology more modern than ancient. Although the concept of reanimated mummies are never mentioned in Egyptian sources, the writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were fascinated by the creepy possibilities they posed as plot devices. With the rise of cinema, mummies were every bit as suitable for celluloid terror as vampires and other monsters and there were several silent mummy-themed movies like The Eyes of the Mummy (1918, released in the U.S. in 1922). However, few of these films actually featured a reanimated mummy. Most dealt with reincarnation and some were comedies in which a character wraps himself up as a mummy in order to scare people.

It wasn’t until 1932 that the definitive mummy movie would make it onto screens. Universal Studios, fresh from their success with Dracula and Frankenstein (both 1931) were looking for a vehicle for their new star, Boris Karloff. They landed on Ancient Egypt, still popular thanks to the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb ten years earlier and all the associated talk of curses. The Mummy tells of Im-Ho-Tep; an Ancient Egyptian priest who was mummified alive for blasphemously attempting to bring back to life his deceased lover, Ankh-es-en-amon using the Scroll of Thoth. Accidentally reanimated by a young Egyptologist involved in uncovering his tomb in 1921, Im-Ho-Tep gets a new lease on life and promptly vanishes, leaving the young scholar to die raving in a madhouse. Ten years later, an expedition of British archaeologists are led to the tomb of Ankh-es-en-amon by a helpful (although decrepit) Egyptian called Ardath Bey. Bey turns out to be none other than Im-Ho-Tep, now mostly restored to human form, who is still looking to reanimate his lost lover. When he encounters Helen Grosvenor – daughter of the governor of the Sudan – he sees in her the reincarnation of Ankh-es-en-amon and decides that she will do instead.

It wasn’t until 1932 that the definitive mummy movie would make it onto screens. Universal Studios, fresh from their success with Dracula and Frankenstein (both 1931) were looking for a vehicle for their new star, Boris Karloff. They landed on Ancient Egypt, still popular thanks to the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb ten years earlier and all the associated talk of curses. The Mummy tells of Im-Ho-Tep; an Ancient Egyptian priest who was mummified alive for blasphemously attempting to bring back to life his deceased lover, Ankh-es-en-amon using the Scroll of Thoth. Accidentally reanimated by a young Egyptologist involved in uncovering his tomb in 1921, Im-Ho-Tep gets a new lease on life and promptly vanishes, leaving the young scholar to die raving in a madhouse. Ten years later, an expedition of British archaeologists are led to the tomb of Ankh-es-en-amon by a helpful (although decrepit) Egyptian called Ardath Bey. Bey turns out to be none other than Im-Ho-Tep, now mostly restored to human form, who is still looking to reanimate his lost lover. When he encounters Helen Grosvenor – daughter of the governor of the Sudan – he sees in her the reincarnation of Ankh-es-en-amon and decides that she will do instead.

Universal’s 1940 follow-up – The Mummy’s Hand – was less of a sequel and more of a remake with the mummy this time around being Kharis, buried alive for attempting to restore his lover, Princess Ananka, using the sacred ‘tana leaves’. Far from being an independent thinker restored to some semblance of his former self like Karloff’s Im-Ho-Tep, Kharis remains under wraps (so to speak) and is under the control of the Priests of Karnak, ordered to kill at the behest of the insideous sect. Kharis is much more of a traditional lumbering monster than Karloff’s articulate and intelligent character and remained so in the three sequels that followed. Set thirty years on in (supposedly) 1970, The Mummy’s Tomb (1942) sees Kharis and his new master travel to the United States to wreak vengeance on the Banning family who desecrated Ananka’s tomb in the first film. The Mummy’s Ghost (1944) is also set in the ‘future’ of 1970 and has a further disciple of the Priests of Karnak (now called the Priests of Arkam, inexplicably) revive Kharis and attempt to return him to Egypt. The final entry in this series – The Mummy’s Curse – was also released in 1944 and is set twenty-five years later, (presumably 1995, despite the hats and spats on show). In this one an engineering company inadvertently dredges up Kharis and his bride, Ananka, from the swamp where they perished in the previous film. The old tana leaves are brewed up once again by a new disciple of the Arkam sect for a final lurch across screens. As with most other Universal monsters, the Mummy got the Abbott and Costello treatment in Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955) which was to be the comedy duo’s final movie together.

Hammer Film Productions – the British heir to Universal’s horror mantle – had already found success with remakes of Dracula and Frankenstein in 1958 and naturally dusted off the Mummy for their next full color outing. The Mummy (1959), starring Hammer stalwarts Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee as John Banning and the mummy respectively, was a remake of The Mummy’s Hand rather than Universal’s 1932 original, although Hammer dispensed with the tana leaves idea and reverted to the ‘Scroll of Thoth’ as a plot device. Hammer borrowed elements from the other Universal mummy movies like the pursuit of John Banning to his homeland (this time Victorian England) by Kharis and his master and the use of a local swamp as both the site of resurrection and eventual fate of Kharis.

Hammer Film Productions – the British heir to Universal’s horror mantle – had already found success with remakes of Dracula and Frankenstein in 1958 and naturally dusted off the Mummy for their next full color outing. The Mummy (1959), starring Hammer stalwarts Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee as John Banning and the mummy respectively, was a remake of The Mummy’s Hand rather than Universal’s 1932 original, although Hammer dispensed with the tana leaves idea and reverted to the ‘Scroll of Thoth’ as a plot device. Hammer borrowed elements from the other Universal mummy movies like the pursuit of John Banning to his homeland (this time Victorian England) by Kharis and his master and the use of a local swamp as both the site of resurrection and eventual fate of Kharis.

Hammer’s other mummy movies bore no relation to their 1959 version or to each other. The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964) had a by-the-numbers plot involving three archaeologists who bring the mummy of Ra-Antef back to 1900s London, only to have it come back to life while on tour. The Mummy’s Shroud (1967) parallels the alleged curse of Tutankhamen in that the mummy of a boy pharaoh, Kah-To-Bey, is discovered by a British expedition in 1920. After bringing the mummy to the Cairo museum, the archaeologists soon find themselves hunted down by the reanimated mummy not of the boy-king, but of the devout slave who mummified him and had subsequently been discovered and kept in the Cairo museum. Hammer’s final mummy movie – Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971) – did not include a mummy per se, but rather the reincarnation of Queen Tera, being a loose adaption of Bram Stoker’s 1903 novel The Jewel of Seven Stars. The queen – found in her tomb perfectly preserved by Professor Fuchs – is brought back to London and kept in an eerie shrine. As in the novel, the professor’s daughter Margaret finds herself gradually possessed by the spirit of the ancient sorceress.

Unlike vampires, zombies and werewolves, mummies did not prove much of a box office draw in the following decades and were relegated to low budget grindhouse movies like Dawn of the Mummy (1981) which is more of a zombie movie with an Egyptian theme. A rare exception is the Charlton Heston starring film The Awakening (1980), another version of The Jewel of Seven Stars. Going direct-to-video in the US, Tale of the Mummy (1998) – also available as a directors cut called Talos the Mummy – has Christopher Lee playing the doomed archaeologist this time, unearthing the tomb of Talos in 1938. Fifty years later his granddaughter strives to continue his work, awakening Talos in the process. 1998 also gave us the direct-to-video feature Bram Stoker’s Legend of the Mummy; yet another version of The Jewel of Seven Stars, its title clearly trying to continue the legacy of the Copploa-produced Bram Stoker’s Dracula/Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein double-punch of 1992/1994. A sequel followed in 1999 (also known as Ancient Evil: Scream of the Mummy) which traded Egypt for an Aztec theme.

In 1999 the mummy movie came back in a big way. Universal Studios decided that their original Boris Karloff feature was due for a remake. But this CGI-filled adventure extravaganza was more reminiscent of Indiana Jones than the atmospheric 1932 chiller. Set in 1926, librarian and Egyptologist Evelyn Carnehan hires mercenary Rick O’Connell to take her to Hamunaptra where, due to the unwise reading of the Book of the Dead, the mummy of disgraced priest Imhotep is brought back to life. Imhotep sees in Evelyn the reincarnation of his lost love Anck-su-Namun and brings with him several spectacular plagues in Biblical style. The Mummy was vastly popular resulting in two sequels; The Mummy Returns (2001) and The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008) which ditched Egypt for China and saw the O’Connell family (including their fully grown son) fend off a resurrected Chinese warlord, yetis and an army of reanimated terracotta warriors.

In 1999 the mummy movie came back in a big way. Universal Studios decided that their original Boris Karloff feature was due for a remake. But this CGI-filled adventure extravaganza was more reminiscent of Indiana Jones than the atmospheric 1932 chiller. Set in 1926, librarian and Egyptologist Evelyn Carnehan hires mercenary Rick O’Connell to take her to Hamunaptra where, due to the unwise reading of the Book of the Dead, the mummy of disgraced priest Imhotep is brought back to life. Imhotep sees in Evelyn the reincarnation of his lost love Anck-su-Namun and brings with him several spectacular plagues in Biblical style. The Mummy was vastly popular resulting in two sequels; The Mummy Returns (2001) and The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008) which ditched Egypt for China and saw the O’Connell family (including their fully grown son) fend off a resurrected Chinese warlord, yetis and an army of reanimated terracotta warriors.

May 18, 2015

Vintage Reads #13 – The Mummy, or Ramses the Damned

Anne Rice, writer of the famous Vampire Chronicles, penned this short stand alone novel in 1989 and, drawing upon the legacy of Universal and Hammer monster movies, succeeded in creating a great modern version of an age old tale set during the wave of Egyptomania of the early twentieth century.

Anne Rice, writer of the famous Vampire Chronicles, penned this short stand alone novel in 1989 and, drawing upon the legacy of Universal and Hammer monster movies, succeeded in creating a great modern version of an age old tale set during the wave of Egyptomania of the early twentieth century.

Opening in 1914, a mysterious tomb is discovered by wealthy archaeologist Lawrence Stratford. There is a mummy and some notes written by the deceased that claim he is none other than Ramses II (the Great). This is regarded as a hoax by most as the mummy of Ramses II had already been discovered by this point and the style and script found in the tomb are from the Ptolemaic period, many hundreds of years after the time of Ramses II.

Ramses’s deal is that he obtained the elixir of life from a Hittite princess and is thus immortal, although often dormant to be ‘regenerated’ by the rays of the sun. He existed in this way for centuries, called upon by the rulers of Egypt for counsel in their times of need. The last to call upon him was Cleopatra who he fell in love with. Needless to say, with Mark Anthony and the birth of the Roman Empire on the horizon, that ended badly.

The villain of the piece is Stratford’s nephew Henry who poisons his uncle shortly after the discovery of the tomb. The mummy is brought back to London and promptly regenerates just in time to stop Henry from trying his poisoning trick on his cousin, Julie. In his new form as a living, breathing Adonis, Ramses quickly has a new lover in the form of Julie. Calling himself Ramsey (see what he did there?) the undead pharaoh immerses himself in the modern world, drinking it all in like a giddy schoolboy.

The villain of the piece is Stratford’s nephew Henry who poisons his uncle shortly after the discovery of the tomb. The mummy is brought back to London and promptly regenerates just in time to stop Henry from trying his poisoning trick on his cousin, Julie. In his new form as a living, breathing Adonis, Ramses quickly has a new lover in the form of Julie. Calling himself Ramsey (see what he did there?) the undead pharaoh immerses himself in the modern world, drinking it all in like a giddy schoolboy.

With the drunken Henry, driven half mad by what he has seen, now obsessed with getting his hands on the elixir, Julie and Ramsey travel to Egypt, intent on seeing the sights. Things don’t go to plan however as Ramsey spots an unidentified mummy in the Cairo museum and, recognizing his old flame Cleopatra, uses the elixir on her resulting in two mummies on the loose.