Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 71

January 11, 2016

Whatever Became of Thomas Paine?

Thomas Paine ©National Portrait Gallery London copy by Auguste Millière, after an engraving by William Sharp, after George Romney oil on canvas, circa 1876

As noted widely this week, one of the most significant pieces of writing in American history was published on January 9, 1776. It was Thomas Paine’s essay Common Sense and is widely credited with helping to rouse Americans to the patriot cause. Its sales were extraordinary at the time; given the American population today, current day sales would amount to some 60 million copies.

The pamphleteering Paine is best known for Common Sense and The Crisis, among other works that supported the cause of independence. But after the Revolution, Paine returned to his native England and later went to France, then in the throes of its Revolution. Paine was caught up in the complex politics of the bloody Revolution there, eventually winding up in a French prison cell, facing the prospect of the guillotine.

After eventually being freed, Paine wrote an open letter in 1796 angrily denouncing President George Washington for failing to do enough to secure his release.

“Monopolies of every kind marked your administration almost in the moment of its commencement. The lands obtained by the Revolution were lavished upon partisans; the interest of the disbanded soldier was sold to the speculator…In what fraudulent light must Mr. Washington’s character appear in the world, when his declarations and his conduct are compared together!”

Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

This was a serious case of bridge-burning and Paine swiftly fell from grace in America. But apart from dissing the Father of the Country, Paine had also fallen from favor for his most famous work after Common Sense. In 1794, he had published The Age of Reason (Part I), a deist assault on organized religion and the errors of the Bible. In it, Paine had written:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

(Source: USHistory.org)

After returning to the United States, which owed so much to him, Paine was regarded as an atheist and was abandoned by most of his friends and former allies. He died in disgrace, an outcast from the United States he had helped create. The Quaker church he had rejected refused to bury him after he died in Greenwich Village (New York) in 1809. He was buried on his farm in New Rochelle, New York. A handful of people attended his funeral.

An admirer brought this remains back to England for reburial there, but they were lost.

You can read more about Thomas Paine, his relationship with Washington and his ultimate fate in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Who Said It? (1/11?16)

…there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Farewell Address to the Nation” (January 17, 1961)

President Eisenhower (Courtesy: Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum)

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger it poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle–with liberty the stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Eisenhower’s farewell is more famous for his use of this phrase:

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

Complete Text and Source: Teaching American History

January 8, 2016

Pop Quiz-Which Presidents Were Quakers?

Answer: Two Presidents were born and raised as Quakers: Herbert Hoover and Richard M. Nixon

Hoover, the 31st President, was born on August 10, 1874. Read a brief biographical post here.

Description: Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover in their Washington, DC home the morning after he was nominated to run for president (1928). (Courtesy: The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum)

Nixon, the 37th President, was born January 9, 1913. Read a brief biographical post here.

Read about both men and their administrations in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About History®

Read about both men and their administrations in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About History®

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

January 2, 2016

Who Said It? (1/2/16)

President George Washington, First Annual Message to Congress (“State of the Union”) January 8, 1790

Knowledge is in every country the surest basis of public happiness.

Nor am I less persuaded that you will agree with me in opinion that there is nothing which can better deserve your patronage than the promotion of science and literature. Knowledge is in every country the surest basis of public happiness. In one in which the measures of government receive their impressions so immediately from the sense of the community as in ours it is proportionably essential.

Source and Full Text: George Washington: “First Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union,” January 8, 1790. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

December 5, 2015

Five Questions for Candidates Who Want to Be Commander in Chief (Update)

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery)

The deadly shootings in California have changed the temperature and the rhetoric on the campaign trail. “After San Bernardino Attack, Republican Candidates Talk ‘War'” (New York Times)

War talk is cheap. But war is costly in both dollars and human lives.

The Reichstag in Berlin, pictured in June 1945. (Source: Imperial War Museum)

That’s why we should pose a set of questions to all of the presidential candidates, some of whom have recently –as the New York Times reported– proposed bombing oil fields in the Middle East (Donald Trump); sending 10,000 American troops to Iraq and Syria (Senator Lindsay Graham of South Carolina); and calling for a United States-led global coalition, including troops on the ground, to take out the Islamic State “with overwhelming force” (Jeb Bush). Hillary Clinton called for a Syrian no-fly zone in a speech made today (Nov. 19, 2015).

As the winds of war talk swirl about Paris, Syria, Iraq and the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL), can the candidates for commander in chief please tell us clearly and specifically —

-As president, would you ask Congress for a declaration of war against the Islamic State?

-As president, would you commit American ground forces to capture and occupy territory in Iraq and Syria now held by the Islamic State?

-If so, how large should that force be and how long would that commitment last?

-Would you make such a commitment unilaterally—without international allies or partners?

-Would you ask the American people to make any sacrifice in undertaking this mission, such as raising taxes to pay for the war effort or reinstating the draft?

Let’s be clear. Under the Constitution, as commander in chief, the president has extraordinary prerogative to take military action without congressional involvement. In the 240 years since the American Revolution began, this country has seldom been free of some kind of military action at home or abroad. Yet American presidents have sent troops into the vast majority of these military conflicts without a formal declaration of war by Congress.

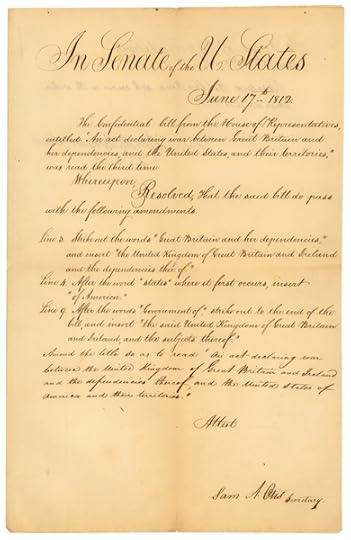

Declaration of the War of 1812 (Courtesy of National Archives)

In fact, in more than two centuries of military actions at home and around the globe, Congress has declared war only five times: against the United Kingdom of Great Britain in 1812, against Mexico, against Spain, and then in World War I and World War II. (Technically, there are eleven “official wars” as both World War I and World War II involved multiple declarations.)

As commander in chief, many presidents have held and exercised almost unchecked power to commit U.S. troops to combat, often with a compliant Congress. From sending marines to fight the Barbary pirates to a decades-long, deadly struggle against the Seminoles of Florida, or chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico and far beyond, America has fought numerous “wars” without calling them that.

The Vietnam-era War Powers Act, enacted over Richard Nixon’s veto in 1973, attempted to correct what Congress and the American public saw as excessive war-making powers in the hands of the president.

It has become far easier for Congress to stand back and stay uninvolved and comfortably ignorant. A vote in favor of a later unpopular decision, as Hillary Clinton learned of her Iraq vote in the Senate, can be an albatross.

And most of the American public has become increasingly disconnected from the sacrifices and costs of military life due to the volunteer nature of our armed services.

Yet it is morally irresponsible to leave the fighting to a modern-day “warrior caste” of men and women in uniform, those who now volunteer, and then look the other way. We need to ask questions about the costs and consequences of both our leaders and candidates and hold them accountable, especially when we are talking about putting our uniformed men and woman in harm’s way.

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

Don’t Know Much About® Van Buren

President Martin Van Buren (Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress)

OK –Literally.

Martin Van Buren, the eighth President of the United States, was born on December 5, 1782 in Kinderhook, New York, making him the first American president born a U.S. citizen. Van Buren was also known as “Old Kinderhook, or “OK,” the origin of that American expression.

Van Buren was also the first New Yorker elected President. He was a crafty political power broker who mastered the art of “machine politics” and helped bring New York into Andrew Jackson’s column in 1828. He became Jackson’s Secretary of State and later his vice president. He won the presidential election of 1836. But his presidency was tainted by the Panic of 1837, a deep economic depression that lasted seven years. He was defeated in 1840 by William Henry Harrison of the Whig Party.

Fast Facts:

•Van Buren was the first president not of English descent. Growing up in a Dutch-speaking household, he was also the only president who spoke English as a second language.

•As a young attorney, he became the protege of Aaron Burr. Due to a passing resemblance and their political and professional connections, it was rumored that he was Burr’s son, gossip thoroughly dismissed by historians.

•Elected Governor of New York in November 1828, Van Buren took the office on January 1, 1829 but resigned on March 12, 1829 to become secretary of state, making him the shortest tenured governor in New York history.

•During Van Buren’s administration, the removal of native Americans from the Southeast accelerated including the removal of the Cherokee on the “Trail of Tears.”

•The Congressional “gag rule” was passed during his presidency; the rule forbid any discussion of petitions relating to slavery, including banning slavery in Washington, D.C, as mentioned in Van Buren’s inaugural address above.

•Failing to win the Democratic nomination in 1844, Van Buren became the first president to run on a third party ticket when he joined the Free Soil Party as its candidate in 1848.

You can read more about his life at the Martin Van Buren Historical Site (National Parks Service)

And read more about Van Buren and his administration in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

November 24, 2015

How the Civil War Created Thanksgiving

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Abraham Lincoln’s second annual Thanksgiving Proclamation had nothing to do with Pilgrims. But it did help create a national tradition.

So it might seem odd that Lincoln chose this moment to announce a national day of thanksgiving, to be marked on the last Thursday in November. His Oct. 3, 1863, proclamation read: “In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity … peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere, except in the theater of military conflict.”

But it took another year for the day to really catch hold. In 1864 Lincoln issued a second proclamation, which read, “I do further recommend to my fellow-citizens aforesaid that on that occasion they do reverently humble themselves in the dust.”

“How the Civil War Created Thanksgiving.” This article, first published on November 25, 2014, in the New York Times “Disunion” blog, explains.

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books Random House Audio)

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

Thanksgiving Pop Quiz- A Videoblog

(Original video created and directed by Colin Davis)

With Thanksgiving around the corner, cutouts of Pilgrims in black clothes and clunky shoes are sprouting all over the place. You may know that the Pilgrims sailed aboard the Mayflower and arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620. But did you know their first Thanksgiving celebration lasted three whole days? What else do you know about these early settlers of America? Don’t be a turkey. Try this True-False quiz.

True or False? (Answers below)

1. Pilgrims always wore stiff black clothes and shoes with silver buckles.

2. The Pilgrims came to America in search of religious freedom.

3. Everyone on the Mayflower was a Pilgrim.

4. The Pilgrims were saved from starvation by a native American friend named Squanto.

5. The Pilgrims celebrated the first Thanksgiving in America.

The site of Plimouth Plantation is definitely worth a visit.

Answers

1. False. Pilgrims wore blue, green, purple and brownish clothing for everyday. Those who had good black clothes saved them for the Sabbath. No Pilgrims had buckles– artists made that up later!

2. True. The Pilgrims were a group of radical Puritans who had broken away from the Church of England. After 11 years of “exile” in Holland, they decided to come to America.

3. False. Only about half of the 102 people on the Mayflower were what William Bradford later called “Pilgrims.” The others, called “Strangers” just wanted to come to the New World.

4. True. Squanto, or Tisquantum, helped teach the Pilgrims to hunt, farm and fish. He learned English after being taken as a slave aboard an English ship.

5. False. The Indians had been having similar harvest feasts for years. So did the English settlers in Virginia and Spanish settlers in the southwest before the Pilgrims even got to America. And the Mayflower Pilgrims weren’t even America’s “first Pilgrims.” That honor goes to French Huguenots who settled in Florida more than 50 years before the Mayflower sailed.

Read about America’s real “first Pilgrims”–French Huguenots who landed in Florida more than fifty years before the Mayflower sailed– in this New York Times Op-Ed, “A French Connection” and in my book America’s Hidden History

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “First Pilgrims” and “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

November 23, 2015

Who Said It? (11/23/2015)

President George Washington issued a proclamation on October 3, 1789, designating Thursday, November 26 as a national day of thanks. It was specifically related to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and had nothing to do with Pilgrims coming on the Mayflower.

That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks…for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed….

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be– That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks–for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation–for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war–for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed–for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted–for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

Source and complete text of Proclamation: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

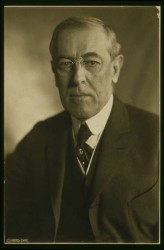

Woodrow Wilson: Racist?

In the wake of the Charleston, S.C. murders in June, the Confederate flag was lowered in many places around the former Confederacy. Other symbols of the Confederacy and America’s racist past have also come into question.

The controversy has now moved to Princeton University, where Woodrow Wilson, who served as the college’s President, has come under fire for his segregationist and racist views and policies. According to the New York Times,

Woodrow Wilson, 1919 (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs digital ID cph.3f06247.)

Born into the manse, or Presbyterian minister’s residence, in Staunton, Virginia (December 28, 1856), Thomas Woodrow Wilson grew up in the Deep South during the Civil War as his father moved the family to Georgia and South Carolina. (He later dropped the first name.)

Woodrow Wilson Birthplace, Staunton, VA (Author Photo © 2010)

A secessionist, his father organized the Presbyterian Church of the Confederate States, and Wilson had a recollection of seeing Robert E. Lee and wounded Confederate soldiers being brought to his father’s church.

At twenty- six Wilson earned his Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins and began writing scholarly works about government and history— including a five- volume History of the American People, completed after he joined the Princeton faculty. In 1902, he was named president.

With the backing of powerful Democrats, he was offered the chance to run for governor of New Jersey and won easily in 1911. When former President Theodore Roosevelt announced his third-party run in 1912, Wilson was all but assured of victory. He somewhat reluctantly led the nation into World War I.

In 1920, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, largely for his efforts to organize the League of Nations which the U.S. Senate rejected.

Generally viewed as a progressive Democrat who tried mightily to keep the nation out of war but was eventually forced into it, Wilson has consistently been ranked among America’s top ten presidents. But like any admired or successful president, he did not have a blotless record. Despite many impressive accomplishments, Wilson had flaws and shortcomings that remain troubling. In one recent assessment, biographer John Milton Cooper, Jr., fairly summed them up: “Two things will always mar his place in history: race and civil liberties. He turned a stone face and deaf ear to the struggle and tribulations of African Americans. . . . During the war, Wilson presided over an administration that committed egregious violations of civil liberties. . . . It remains a mystery why such a farseeing, thoughtful person as Wilson would let any of that occur.” (Woodrow Wilson, p.11)

The first answer is his upbringing. Although not a fire-breathing white supremacist, he was a product of his birth into a slaveholding house hold with Confederate loyalty. His heritage, and the times, played a role. The second is politics. Keeping a Democratic Southern Congress quiescent required Wilson— and many of his successors in the White House— to tread lightly on matters of race.

Adapted from DON’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT THE AMERICAN PRESIDENTS. Read more about Wilson and his presidency.

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

In a recent article, Georgetown University law Center’s Randy Barnett offered a detailed rational for reconsidering Wilson in light of his views.

Now that we are expunging the legacy of past racism from official places of honor, we should next remove the name Woodrow Wilson from public buildings and bridges. Wilson’s racist legacy — in his official capacity as President — is undisputed.

Randy Barnett, Professor law at Georgetown University law Center and Director of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution, wrote “Expunging Woodrow Wilson from Official Places of Honor” in the Washington Post (June 25, 2015).