Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 72

November 23, 2015

Don’t Know Much About® the Real First Pilgrims

Always a good time to remember the “Real First Pilgrims”

As we cut through the myth and misconception surrounding the “first Thanksgiving,” it is easy to say that there was nothing new or novel about the October 1621 “harvest feast” celebrated in Massachusetts by the surviving Mayflower passengers. Certainly harvest festivals go back to the dawn of time. And in America, such “thanksgiving days” were surely celebrated by the Spanish in the Southwest and Englishmen in Virginia well before the Mayflower sailed.

But one group has been left out of the picture completely. And their story deserves to be part of the Thanksgiving conversation. They were French and had the good sense to settle in Florida in June instead of Massachusetts in December. They reached the future America in 1564, long before the Mayflower arrived in December 1620 carrying those “Pilgrims.” Like the storied English Separatists, these French Protestants, or Huguenots, came to America seeking religious freedom in the midst of France’s bloody religious civil wars. But they have been overlooked by most history books. Their plight — and tragic fate– is the subject of an article I wrote for the New York Times.

TO commemorate the arrival of the first pilgrims to America’s shores, a June date would be far more appropriate, accompanied perhaps by coq au vin and a nice Bordeaux. After all, the first European arrivals seeking religious freedom in the “New World” were French. And they beat their English counterparts by 50 years. That French settlers bested the Mayflower Pilgrims may surprise Americans raised on our foundational myth, but the record is clear.

Here you can read the rest of this Op-Ed, A French Connection which first appeared in the New York Times on November 25, 2008.

The complete story of the French Huguenots who settled Fort Caroline in Florida is told in the first chapter of America’s Hidden History.

You can also learn more about the “first Pilgrims” at the Fort Caroline and Fort Matanzas National Park Service sites.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

November 19, 2015

Five Questions for Candidates Who Want to Be Commander in Chief

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery)

War talk is cheap. But war is costly in both dollars and human lives.

The Reichstag in Berlin, pictured in June 1945. (Source: Imperial War Museum)

That’s why we should pose a set of questions to all of the presidential candidates, some of whom have recently –as the New York Times reported– proposed bombing oil fields in the Middle East (Donald Trump); sending 10,000 American troops to Iraq and Syria (Senator Lindsay Graham of South Carolina); and calling for a United States-led global coalition, including troops on the ground, to take out the Islamic State “with overwhelming force” (Jeb Bush). Hillary Clinton called for a Syrian no-fly zone in a speech made today (Nov. 19, 2015).

As the winds of war talk swirl about Paris, Syria, Iraq and the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL), can the candidates for commander in chief please tell us clearly and specifically —

-As president, would you ask Congress for a declaration of war against the Islamic State?

-As president, would you commit American ground forces to capture and occupy territory in Iraq and Syria now held by the Islamic State?

-If so, how large should that force be and how long would that commitment last?

-Would you make such a commitment unilaterally—without international allies or partners?

-Would you ask the American people to make any sacrifice in undertaking this mission, such as raising taxes to pay for the war effort or reinstating the draft?

Let’s be clear. Under the Constitution, as commander in chief, the president has extraordinary prerogative to take military action without congressional involvement. In the 240 years since the American Revolution began, this country has seldom been free of some kind of military action at home or abroad. Yet American presidents have sent troops into the vast majority of these military conflicts without a formal declaration of war by Congress.

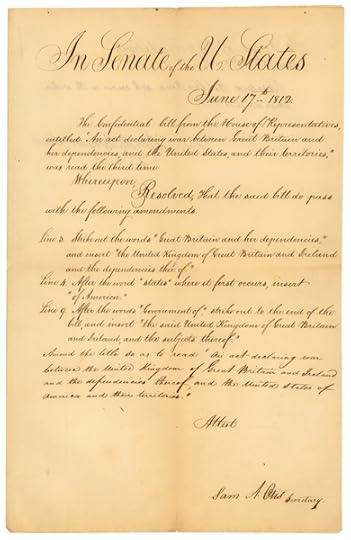

Declaration of the War of 1812 (Courtesy of National Archives)

In fact, in more than two centuries of military actions at home and around the globe, Congress has declared war only five times: against the United Kingdom of Great Britain in 1812, against Mexico, against Spain, and then in World War I and World War II. (Technically, there are eleven “official wars” as both World War I and World War II involved multiple declarations.)

Congressional resolutions authorizing action that are remarkably flexible –and often very expensive and long-lived—are probably not what the framers of the Constitution had in mind. On the other hand, they didn’t want standing professional armies either.

As commander in chief, many presidents have held and exercised almost unchecked power to commit U.S. troops to combat, often with a compliant Congress. From sending marines to fight the Barbary pirates to a decades-long, deadly struggle against the Seminoles of Florida, or chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico and far beyond, America has fought numerous “wars” without calling them that.

The Vietnam-era War Powers Act, enacted over Richard Nixon’s veto in 1973, attempted to correct what Congress and the American public saw as excessive war-making powers in the hands of the president. U.S. presidents have consistently taken the position that the War Powers Resolution is an unconstitutional infringement upon the power of the executive branch and its terms have rarely been invoked.

It has become far easier for Congress to stand back and stay uninvolved and comfortably ignorant. A vote in favor of a later unpopular decision, as Hillary Clinton learned of her Iraq vote in the Senate, can be an albatross.

And most of the American public has become increasingly disconnected from the sacrifices and costs of military life due to the volunteer nature of our armed services.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered

Yet it is morally irresponsible to leave the fighting to a modern-day “warrior caste” of men and women in uniform, those who now volunteer, and then look the other way. We need to ask questions about the costs and consequences of both our leaders and candidates and hold them accountable, especially when we are talking about putting our uniformed men and woman in harm’s way.

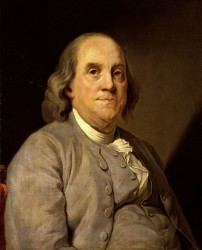

After the American Revolution officially ended, Benjamin Franklin said,

“There never was a good war or a bad peace.”

Franklin was wrong. There are just wars and there are necessary wars –fought, as the preamble to the Constitution puts it, “For the common defense.”

Before we “let slip the dogs of war,” let’s hear the case made for that terrible decision in the clearest way. Let’s hear the answers to these questions.

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

November 18, 2015

“The Founding Immigrants” Revisited

The debate over immigration and refugees –two different things– is back. Some historical perspective:

A PROMINENT American once said, about immigrants, ”Few of their children in the country learn English… The signs in our streets have inscriptions in both languages … Unless the stream of their importation could be turned they will soon so outnumber us that all the advantages we have will not be able to preserve our language, and even our government will become precarious.”

The speaker was Ben Franklin.

Benjamin Franklin (National Portrait Gallery)

Back in 2007, I wrote “The Founding Immigrants” for the New York Times Op-Ed page as the debate over immigration policies raged back then.

In it, I wrote

Scratch the surface of the current immigration debate and beneath the posturing lies a dirty secret. Anti-immigrant sentiment is older than America itself. Born before the nation, this abiding fear of the ”huddled masses” emerged in the early republic and gathered steam into the 19th and 20th centuries, when nativist political parties, exclusionary laws and the Ku Klux Klan swept the land.

History does repeat.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

November 16, 2015

Who Said It (11/16/2015)

“…we cannot hallow this ground.”

Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863)

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion–that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

Source: Avalon Project-Yale Law School

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery)

Check out the Ken Burns site Learn the Address

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books/Random House Audio)

November 8, 2015

Who Said It? (11/8/15)

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

…to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan…

Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address (March 4, 1865)

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Full text and Source: Yale Law School-The Avalon Project

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery)

Lincoln’s words became the motto of the Department of Veterans Affairs in 1959. Read about the origins of Veterans Day here.

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion/Random House Audio)

November 4, 2015

11-11-11: Don’t Know Much About Veterans Day-The Forgotten Meaning

“The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.”

(This is a revised version of a post originally written for Veterans Day in 2011. The meaning still applies.)

Taken at 10:58 a.m., on Nov. 11, 1918, just before the Armistice went into effect; men of the 353rd Infantry, near a church, at Stenay, Meuse, wait for the end of hostilities. (SC034981)

On Veterans Day, a reminder of what the day once meant and what it should still mean.

That was the moment at which World War I –then called THE GREAT WAR– largely came to end in 1918. on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

One of the most tragically senseless and destructive periods in all history came to a close in Western Europe with the Armistice –or end of hostilities between Germany and the Allied nations — that began at that moment. Some 20 million people had died in the fighting that raged for more than four years since August 1914. The complete end of the war came with the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

The date of November 11th became a national holiday of remembrance in many of the victorious allied nations –a day to commemorate the loss of so many lives in the war. And in the United States, President Wilson proclaimed the first Armistice Day on November 11, 1919. A few years later, in 1926, Congress passed a resolution calling on the President to observe each November 11th as a day of remembrance:

Whereas the 11th of November 1918, marked the cessation of the most destructive, sanguinary, and far reaching war in human annals and the resumption by the people of the United States of peaceful relations with other nations, which we hope may never again be severed, and

Whereas it is fitting that the recurring anniversary of this date should be commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations; and

Whereas the legislatures of twenty-seven of our States have already declared November 11 to be a legal holiday: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring), that the President of the United States is requested to issue a proclamation calling upon the officials to display the flag of the United States on all Government buildings on November 11 and inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches, or other suitable places, with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

Of course, the hopes that “the war to end all wars” would bring peace were short-lived. By 1939, Europe was again at war and what was once called “the Great War” would become World War I. With the end of World War II, there was a movement in America to rename Armistice Day and create a holiday that recognized the veterans of all of America’s conflicts. President Eisenhower signed that law in 1954. (In 1971, Veterans Day began to be marked as a Monday holiday on the third Monday in November, but in 1978, the holiday was returned to the traditional November 11th date).

Today, Veterans Day honors the duty, sacrifice and service of America’s nearly 25 million veterans of all wars, unlike Memorial Day, which specifically honors those who died fighting in America’s wars.

We should remember and celebrate all those men and women. But lost in that worthy goal is the forgotten meaning of this day in history –the meaning which Congress gave to Armistice Day in 1926:

to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations …

inviting the people of the United States to observe the day … with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

The Library of Congress offers an extensive Veterans History Project.

The Veterans Administration website offers more resources on teaching about Veterans Day.

Read more about World War I and all of America’s conflicts in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

I discuss the role of Americans in battle in more than 240 years of American history in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah (Hachette Books and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback and Random House audio)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

October 31, 2015

Don’t Know Much About® Halloween–The Hidden History

(Video directed and produced by Colin Davis)

When I was a kid in the early 1960s, the autumn social calendar was highlighted by the Halloween party in our church. In these simpler day, the kids all bobbed for apples and paraded through a spooky “haunted house” in homemade costumes –Daniel Boone replete with coonskin caps for the boys; tiaras and fairy princess wands for the girls. It was safe, secure and innocent.

The irony is that our church was a Congregational church — founded by the Puritans of New England. The same people who brought you the Salem Witch Trials.

Here’s a link to a history of those Witch Trials in 1692.

Rooted in pagan traditions more than 2000 years old, Halloween grew out of a Celtic Druid celebration that marked summer’s end. Called Samhain (pronounced sow-in or sow-een), it combined the Celts’ harvest and New Year festivals, held in late October and early November by people in what is now Ireland, Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe. This ancient Druid rite was tied to the seasonal cycles of life and death — as the last crops were harvested, the final apples picked and livestock brought in for winter stables or slaughter. Contrary to what some modern critics believe, Samhain was not the name of a malevolent Celtic deity but meant, “end of summer.”

The Celts also saw Samhain as a fearful time, when the barrier between the worlds of living and dead broke, and spirits walked the earth, causing mischief. Going door to door, children collected wood for a sacred bonfire that provided light against the growing darkness, and villagers gathered to burn crops in honor of their agricultural gods. During this fiery festival, the Celts wore masks, often made of animal heads and skins, hoping to frighten off wandering spirits. As the celebration ended, families carried home embers from the communal fire to re-light their hearth fires.

Getting the picture? Costumes, “trick or treat” and Jack-o-lanterns all got started more than two thousand years ago at an Irish bonfire.

Christianity took a dim view of these “heathen” rites. Attempting to replace the Druid festival of the dead with a church-approved holiday, the seventh-century Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor saints and martyrs. Then in 1000 AD, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to remember the departed and pray for their souls. Together, the three celebrations –All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls Day– were called Hallowmas, and the night before came to be called All-hallows Evening, eventually shortened to “Halloween.”

And when millions of Irish and other Europeans emigrated to America, they carried along their traditions. The age-old practice of carrying home embers in a hollowed-out turnip still burns strong. In an Irish folk tale, a man named Stingy Jack once escaped the devil with one of these turnip lanterns. When the Irish came to America, Jack’s turnip was exchanged for the more easily carved pumpkin and Stingy Jack’s name lives on in “Jack-o-lantern.”

Halloween, in other words, is deeply rooted in myths –ancient stories that explain the seasons and the mysteries of life and death.

You can read more about ancient myths in the modern world in Don’t Know Much About Mythology and more about the Salem Witch Trials in Don’t Know Much About History.

Don’t Know Much About Mythology (Harper paperback/Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

October 30, 2015

Speaking Nov. 1– Bar Harbor, Maine

Please join me on SUNDAY NOVEMBER 1 at the JESUP MEMORIAL LIBRARY in Bar Harbor, Maine for a discussion of THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: 2-3:30 PM

For more Information and directions to the Library

The Hidden History of America At War-May 5, 2015 (Hachette Books/Random House Audio)

October 23, 2015

EVENT: October 29 -Camden (Maine) Public Library

Author Kenneth C. Davis will visit the Camden Public Library as part of “Discover History Month,” on Thursday evening, October 29, at 7:00 pm. Davis will be talking about his latest book, The Hidden History of America at War: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah, just published in May. Davis is also the author of Don’t Know Much About History, which spent 35 consecutive weeks on The New York Times bestseller list, and gave rise to the “Don’t Know Much About” series of books and audios. Don’t Know Much About History presents a complete survey of American history, from before the arrival of Columbus in 1492 right through the events of the past decade –from 9/11 through the election of Barack Obama and the first years of his administration.

The Hidden History of America at War is a unique, myth-shattering, and insightful look at war—why we fight, who fights our wars and what we need to know but perhaps never learned about  the growth and development of America’s military forces. Starting with the founding of the nation and on through the war in Iraq, Davis provides an in-depth examination based on his belief that it is “nearly a moral imperative to understand war.” Arguing that from its earliest days, America has had an uneasy relationship with the military, Davis charts how our country’s military developed from a group of rag-tag “citizen soldiers” in 1775 to the high-tech, global and increasingly privatized organization it is today, and what we can learn from that transformation. Davis makes his case through rich storytelling and analysis of six landmark battles: Yorktown, Virginia – October 1781; Petersburg, Virginia – June 1864; Balangiga, Philippines – September 1901; Berlin, Germany – April 1945; Hué, South Vietnam – February 1968; and Fallujah, Iraq – March 2004.

the growth and development of America’s military forces. Starting with the founding of the nation and on through the war in Iraq, Davis provides an in-depth examination based on his belief that it is “nearly a moral imperative to understand war.” Arguing that from its earliest days, America has had an uneasy relationship with the military, Davis charts how our country’s military developed from a group of rag-tag “citizen soldiers” in 1775 to the high-tech, global and increasingly privatized organization it is today, and what we can learn from that transformation. Davis makes his case through rich storytelling and analysis of six landmark battles: Yorktown, Virginia – October 1781; Petersburg, Virginia – June 1864; Balangiga, Philippines – September 1901; Berlin, Germany – April 1945; Hué, South Vietnam – February 1968; and Fallujah, Iraq – March 2004.

“His searing analyses and ability to see the forest as well as the trees make for an absorbing and infuriating read as he highlights the strategic missteps, bad decisions, needless loss of life, horrific war crimes, and political hubris that often accompany war.” (PUBLISHERS WEEKLY-Starred Review)

October 21, 2015

THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR-Speaking Calendar

List of Upcoming Speaking Engagements:

The lawn outside the Camden (Me.) Public Library and Camden Harbor

Thursday October 29 Camden Public Library Camden, Maine 7 PM

Sunday November 1 Jesup Memorial Library Bar Harbor, Maine 2-3:30 PM

THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah (May 5-Hachette Books/Random House Audio)