Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 69

March 11, 2016

Don’t Know Much About® Fascism

In the midst of the current presidential campaign, the word “fascist” has been tossed about quite a bit. It is the political “F-word,” most associated with World War II dictators, Italy’s Benito Mussolini and Germany’s Adolf Hitler.

Hitler (r) and Mussolini (l) ca. June 1940. Part of Eva Braun’s Photo Albums, ca. 1913 – ca. 1944, seized by the U.S. government. This image is available from the Online Public Access (OPA) of the United States National Archives and Records Administration under the National Archives Identifier 540151. (Source: National Archives.

Lately, the term has been used specifically with respect to Republican frontrunner Donald Trump. Conservative columnist Ross Douthat asked in a New York Times Op-Ed “Is Donald Trump a Fascist?”

But what does this widely used word “fascist” mean?

Generally, fascism describes a military dictatorship built on racist and powerfully nationalistic foundations, generally with the broad support of the business class (distinguishing it from the collectivism of Communism).

Benito Mussolini (1883–1945), called Il Duce (which simply means “the leader”), was the son of a blacksmith, who came to power as prime minister in 1922. A preening bully of a man, he organized Italian World War I veterans into the anti-Communist and rabidly nationalistic “blackshirts,” a paramilitary group that used gang tactics to suppress strikes and attack leftist trade unions.

In 1925, Mussolini installed himself as head of a single-party state he called fascismo. The word came from fasces, a Latin word referring to a bundle of rods bound around an ax, which had been an ancient Roman symbol of authority and strength.

Flag of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Italy first used in 1927 when Benito Mussolini served as Prime Minister. The flag was used until 1943, when Fascism was banned in Italy. (Source: Wikipedia Public Domain)

Mussolini blamed Italy’s problems on foreigners, and promised to make the trains run on time. (Contrary to popular belief, he did not.)

The rise to power of the three militaristic, totalitarian states that would form the wartime Axis—Germany, Japan, and Italy—as well as Fascist Spain under General Franco, can be laid to the aftershocks, both political and economic, of the First World War. It was rather easy, especially in the case of Germany and Italy, for demagogues to point to the smoldering ruins of their countries and the economic disaster of the worldwide Depression and blame their woes on foreigners.

In Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) made scapegoats not only of the Communists and foreign powers who he claimed had stripped Germany of its land and military abilities at Versailles, but also of Jews, who he claimed were in control of the world’s finances.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Mussolini (l) and Hitler (r) in Berlin, 1937 (publishers Vitézi rend Zrinyi csoportjuának kiadása, Budapest, 1939) (Source: Wikipedia Public Domain)

(This text is adapted from Don’t Know Much About® History, “Who were the Fascists?” pages 361-365).

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Read more about Hitler and Mussolini in The Hidden History of America at War.

In paperback May 2016 THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® Eli Whitney (A TED-Ed “Lesson Worth Sharing”)

“Eli Whitney,” portrait of the inventor, oil on canvas, by the American painter Samuel F. B. Morse. 35 7/8 in. x 27 3/4 in. Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

On March 14, 1793, Eli Whitney received a patent for the machine known as the Cotton Gin. Here is a short video about the Connecticut-born inventor’s most famous “invention,” the Cotton Gin. This was created as my first contribution to Ted-Ed: “Lessons Worth Sharing.”

This portrait of the inventor is by another inventor– Samuel F.B. Morse who was a well-known painter and art teacher before he gained fame for the development of the telegraph and the Morse Code.

The cotton gin changed history for good and bad. By allowing one field hand to do the work of 10, it powered a new industry that brought wealth and power to the American South — but, tragically, it also multiplied and prolonged the use of slave labor. In this video, I discuss innovation, while warning of unintended consequences.

Eli Whitney died in New Haven, Connecticut on January 8, 1825. You can learn more about Whitney and his inventions at the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop.

Read more about the history and impact of American slavery in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the Civil War and my forthcoming book In The Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Five Black Lives. (Holt Books, Sept. 20, 2016)

In the Shadow of Liberty (September 20, 2016)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War

March 10, 2016

“The Myth of America’s Genteel Political History”

In the heat of the presidential campaign, the mudslinging has Americans once again complaining about negative politics. People say they yearn for the “good old days” when elections were more polite affairs. But the truth is that American presidential politics has been a nasty business from the first contested elections.

This audio essay, “The Myth of Americas Genteel Political History,” is a Commentary I wrote for for NPR’S “All Things Considered.” It is worth noting that it originally aired in October 2004.

As the saying goes, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

March 3, 2016

The “Slave Act of 1807:” A False Step Toward Abolition

Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States (Source: White House)

On March 3, 1807, President Thomas Jefferson signed into law a bill approved by Congress the day before “to prohibit the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States.”

The 1807 act, which would go into effect on January 1, 1808, was a comprehensive attempt to shut down the foreign slavery trade. Congress gave all traders nine months to cease their operations in the United States.

The 1807 Act was born out of language written into the original Constitution, debated and drafted in the summer of 1787:

The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

-Article I, Section 9

Slaveholding delegates, unwilling to accept a Constitution that placed any limits on American slavery, saw this as a victory. It protected the foreign trade for another twenty years and provided no guarantee that the trade in enslaved people would end. And it prompted a vast increase in the importation of enslaved Africans:

During this period, labor hungry planters in the lower South imported tens of thousands of Africans; indeed, more slaves entered the United States between 1787 and 1807 than during any two decades in history.

–Peter Kolchin, American Slavery (Hill & Wang, 1993), p. 79

Of course, the end of the legal importation of enslaved people sounds like a good thing. Optimists at the Constitutional convention in 1787 and in Congress in 1807 saw the end of the foreign trade as a necessary first step to the ultimate end of slavery in America. They were woefully wrong.

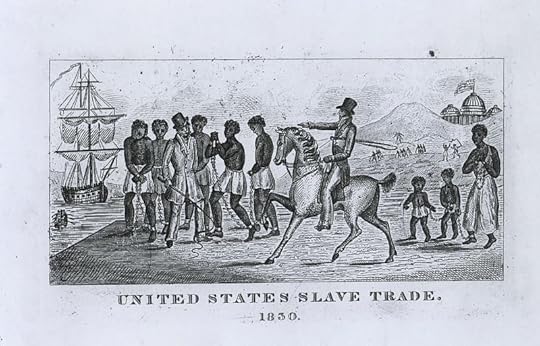

U.S. Slave Trade 1830 (Image Courtesy of Smithsonian Museum of American History)

The end of the legal foreign trade –illegal smuggling of enslaved Africans would continue– only created a large and more profitable internal market for the enslaved by forcing up the value of enslaved people, even as demand from cotton growers was increasing.

The 1807 act sought to end the trade, but did nothing to undermine the legitimacy holding men and women in bondage.

(Source: “The Abolition of the Slave Trade,” New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

Large holders of enslaved people in essence became even more wealthy as breeders of enslaved people. In 1800, there were about one million enslaved people in America. By 1860, at the outbreak of the Civil War, there were nearly four million.

Expectations that ending the African slave trade would put slavery on the road to gradual extinction proved radically wide of the mark. During the half century after the legal end of slave importation, the slave population of the United States surpassed that of any other country in the New World….

–Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, p. 94

While a milestone of sorts in the abolition movement, the Slave Act of 1807 merely cemented the financial and political value of slavery for generations to come and did precious little to bring about its end.

Read more about the role of slavery in American history in my books:

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

The subject is also at the center of my forthcoming book In The Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives. (Holt Books for Young Readers; September 20, 2016 publication date)

In the Shadow of Liberty (September 20, 2016)

March 2, 2016

Kenneth C. Davis-Speaking Calendar

Photo credit Nina Subin

2016

•Friday April 29 Rutland Free Library 5 PM

10 Court Street Rutland, Vermont “Tables of Content”

•Tuesday May 3 Oregon Historical Society “Mark O. Hatfield Distinguished Historians Forum” 7 PM

First Congregational United Church of Christ, 1126 SW Park Avenue, Portland, Oregon

In paperback May 2016 THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

•TUESDAY JUNE 28 BELFAST, ME

“The Myths and Hidden History of the American Revolution”

Belfast Free Library Abbott Room 6:30 PM

106 High Street, Belfast, Maine

Telephone: (207) 338-3884

In the Shadow of Liberty- Publication date September 20, 2016 (Holt Books for Young Readers)

•Thursday September 22 Fraunces Tavern Museum (Time TBA)

54 Pearl Street New York City

•Thursday October 6 Northshire Bookstore (Saratoga Springs, NY) 5:30 PM

424 Broadway, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866

•Friday October 7 Northshire Bookstore (Manchester, VT) TIME TBA

4869 Main ST, Manchester Center, VT 05255

How One President Helped Save College Football

There are no “tackling dummies” in the Ivy League, one might assume.

Photo credit: Jim Cole AP via the New York Times

As the college and professional football world continue to address the growing concern over severe injuries, football coaches in the Ivy League are moving to eliminate full-contact hitting from practices, reports the New York Times.

The latest controversies over concussions and other injuries are nothing new. More than 100 years ago, college football – was faced with possible extinction as the game had grown so violent and corrupt. But a football-loving President helped save the sport.

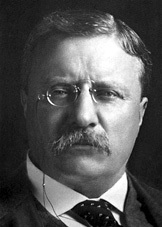

Theodore Roosevelt (Photo Source: NobelPrize.org)

More than a century ago, before there was a true professional league, cash payments were made to “amateur” college athletes. Coaches gave orders to take out rivals on the field. In the sport’s primitive era, body blows, concussions, spinal injuries and even blood poisoning — the result of on-field savagery that included late hits, punching, kneeing, eye-gouging and vicious blows to the windpipe — often proved fatal. In 1905, these abuses and catastrophic injuries were so widespread, and public disapproval of them so deep, the game faced extinction. Football was saved, in part, by the intervention of the American president.

President Theodore Roosevelt, a fan of the sport –he was too small to play at Harvard– wanted to make sure that the game survived. Using his “bully pulpit,” Theodore Roosevelt stepped in. I wrote the story of how he did it in this New York Times Op-Ed, “Schools of Hard Knocks.”

Some other presidential football tidbits: Dwight D. Eisenhower wanted to play for Army but could not and became a cheerleader. Gerald Ford was a highly touted offensive lineman at Michigan who turned down pro offers.

Read more about Theodore Roosevelt, Ike and Ford in…

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

February 29, 2016

Who Said It? (2/29/2016)

President Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address (March 4, 1865)

Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural (March 4, 1865) Photo Courtesy of the Library of C0ngress

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Source and complete text: The Avalon Project-Yale University

Read more:

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

The Hidden History of America At War-May 5, 2015 (Hachette Books/Random House Audio)

“Two Societies, One Black, One White”

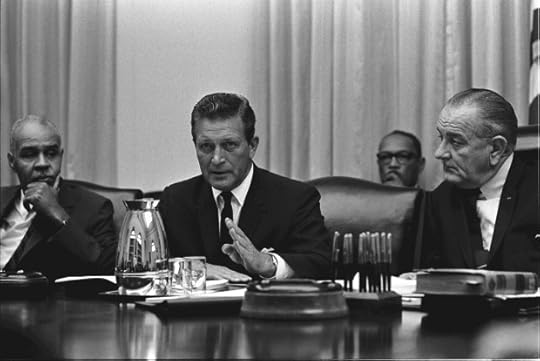

On Feb. 29, 1968, President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (also known as the Kerner Commission) warned that racism was causing America to move “toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.” (New York Times account.)

Grand Rapids Michigan-1967

Responding to a series of violent outbursts in predominantly black urban neighborhoods, President Lyndon B. Johnson established an 11-member National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders on July 28, 1967.

Governor of Illinois Otto Kerner, Jr., meeting with Roy Wilkins (left) and President Lyndon Johnson (right) in the White House. 29 July 1967 Source LBJ Presidential Library

Later known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman, Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. of Illinois, the Commission issued a stark warning in 1968:

“Our Nation Is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”

The Committee Report went on to identify a set of “deeply held grievances” that it believed had led to the violence.

Although almost all cities had some sort of formal grievance mechanism for handling citizen complaints, this typically was regarded by Negroes as ineffective and was generally ignored.

Although specific grievances varied from city to city, at least 12 deeply held grievances can be identified and ranked into three levels of relative intensity:

First Level of Intensity

1. Police practices

2. Unemployment and underemployment

3. Inadequate housing

Second Level of Intensity

4. Inadequate education

5. Poor recreation facilities and programs

6. Ineffectiveness of the political structure and grievance mechanisms.

Third Level of Intensity

7. Disrespectful white attitudes

8. Discriminatory administration of justice

9. Inadequacy of federal programs

10. Inadequacy of municipal services

11. Discriminatory consumer and credit practices

12. Inadequate welfare programs

Source: “Our Nation is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”: Excerpts from the Kerner Report; American Social History Project / Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY)

and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University).

Issued nearly half a century ago, the list of grievances reads as if it could have been written last week.

The Kerner Commission’s warnings still ring true: “Moving Toward Two Societies…Separate and Unequal.”

Read more about the unrest of the Civil Rights era in Don’t Know Much About® History. The crucial role of race in the American military is also treated in The Hidden History of America at War. (May 5)

The Hidden History of America At War-May 5,2015 (Hachette Books/Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

February 22, 2016

Who Said It? (2/22/2016)

President George Washington, “Letter to the Jewish congregation of Newport, Rhode Island” (1790)

Happily the Government of the United States, which gives

to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

The complete text and story of Washington’s letter to the Touro Synagogue can be found at the George Washington Institute for Religious Freedom.

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732.

February 20, 2016

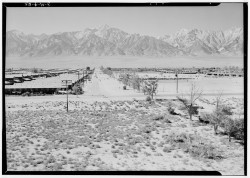

Don’t Know Much About® Ansel Adams

Burning leaves, autumn dawn, Manzanar Relocation Center, California Source: Library of Congress

Digital ID: (digital file from original print) ppprs 00308 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppprs.00308

(Revision of post originally published in 2012)

Born today –February 20 in 1902– a man who changed how we see the world, Ansel Adams.

It was the photography that launched a thousand calendars, posters, and greeting cards. You have seen his ethereal outdoor photography –maybe even if you did not know it.

But his birthdate follows by one day the anniversary of one of his most important subjects, the Internment of Japanese Americans during World War II –the policy created on February 19, 1942 by FDR’s Executive Order 9066.

In 1943, Adams photographed Manzanar, the Japanese internment camp. The Library of Congress offers an online exhibit of Adams’ wartime photos of Japanese Americans.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Ansel Adams, photographer, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-DIG-ppprs-00257

Of the photographs, Adams wrote, “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment…

In earlier posts, I have written more about Executive Order 9066 and photographer Dorothea Lange’s work documenting the internment of Japanese Americans

Adams died at age 82 on April 22, 1984. Here is his New York Times obituary.