Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 112

April 25, 2011

Don't Know Much About® Poetic Last Lines

it's the final Last week of National Poetry Month. So fittingly, here's a Pop Quiz on some notable closing lines of poems.

"Nevermore!" It might be difficult to end a poem on a more dramatic note than Edgar Allen Poe did in "The Raven." Can you name the poets who created these ending lines? Bonus points for the name of the poem.

1. Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

2. My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

3. and so cold

4. And eternity in an hour

5. Petals on a wet, black bough.

6. Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I'm through.

Adapted from Don't Know Much About Literature, a collection of literary quizzes I wrote in collaboration with Jenny Davis.

Answers

1. T.S. Eliot, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

2. Langston Hughes, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers"

3. William Carlos Williams, "This Is Just To Say"

4. William Blake, "To see a world in a grain of sand"

5. Ezra Pound, "In a Station of the Metro"

6. Sylvia Plath, "Daddy"

April 22, 2011

Poetry Pop Quiz #2

In honor of National Poetry Month in April, I posted a quiz on poetic first lines earlier this month. Here is another.

(If you've been following my Poem of the Day posts all month on my Facebook page or on Twitter, you should recognize several of these. All are worth reading. Or rereading!)

"Gather ye rose-buds while ye may," wrote Robert Herrick, the 17th Century English poet, to open a poem encouraging ladies to marry while they were young and beautiful ("To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time"). This line of Herrick's poem, which gained popularity as a song, is now an iconic admonition to enjoy our lives on Earth. Now gather ye wits, and see how many of these famous first lines you can identify.

1. Something there is that doesn't love a wall

2. I, too, dislike it, there are things that are important beyond all this fiddle

3. Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

4. By the rude bridge that arched the flood

5. Come live with me and be my love

6. God moves in a mysterious way,

7. Hog Butcher for the World

8. Little Lamb, who made thee?

9. The art of losing isn't hard to master.

The answers are below. This quiz was adapted from Don't Know Much About Literature, written in collaboration with Jenny Davis.

Answers

1. Robert Frost, "Mending Wall"

2. Marianne Moore, "Poetry"

3. Wilfred Owen, "Dulce et Decorum Est"

4. Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Concord Hymn"

5. Christopher Marlowe, "The Passionate Shepherd to His Love"

6. William Cowper, "Light Shining Out of Darkness"

7. Carl Sandburg, "Chicago"

8. William Blake, "The Lamb"

9. Elizabeth Bishop, "One Art"

April 18, 2011

Don't Know Much About® the Bay of Pigs

In the long catalog of America's recent foreign policy fiascoes, the Bay of Pigs Invasion occupies a lofty position among the worst debacles. The 50th anniversary of the failed CIA-sponsored invasion of Cuba begun on April 17, 1961 is now being quietly marked. In Cuba, it is still a cause for celebration.

During the past 50 years, Communism rose and fell in Europe, relations with Red China were transformed, and Middle Eastern tyrants were embraced, tolerated or toppled. But the Cuba of Fidel Castro has remained a stubborn thorn for every American President since Dwight D. Eisenhower. Castro's regime, which took over Cuba in a 1958 revolution, has survived coups, assassination plots, economic war and one attempted invasion.

What: For most of the 20th century, the Cuban economy –all the sugar, mining, cattle, and oil wealth– was in nearly total American control. American gangsters had a rich share of the casinos and hotels of Havana. The Spanish-American War had also given the United States the base it still controls at Guantanamo. Then Castro and his rebels took over and turned the island into a Soviet-dominated Communist state. Almost since the time Castro came to power, the CIA began to plan his overthrow.

Who: In 1961, the CIA plotted to invade Cuba with a small army of anti-Castro refugees and exiles called La Brigada. Supported by CIA-planted insurgents in Cuba who would blow up bridges and knock out radio stations, the brigade would land on the beaches of Cuba and set off a popular revolt against Fidel Castro.

When: On April 17, 1961, some 1,400 Cubans, poorly trained, under-equipped, and uninformed of their destination, were set down on the beach at the Bay of Pigs.

By the end of the day on April 19, the invasion was over– a total disaster for the Cuban exile army. The toll was 114 Cuban invaders and many more defenders killed in the fighting; 1,189 other exiles were captured and held prisoner until they were later ransomed from Cuba by then- Attorney General Robert Kennedy for food and medical supplies. Four American fliers, members of the Alabama Air National Guard in CIA employ, also died as part of the invasion, but the American government never acknowledged their existence or their connection to the operation.

Why: Poor planning, dated information about Cuba, and a complete lack of coordination doomed the ill-fated invasion force. Once the assault was underway, Castro poured thousands of troops into the area. Overwhelmed, the brigade fought bravely, but they lacked ammunition and, most important, the air support promised by the CIA. In Washington, Kennedy feared that any direct U.S. combat involvement might send the Russians into the non-Communist enclave of West Berlin, possibly setting off World War III.

The abject failure of the invasion was a total American humiliation. And it would bring Cold War America to its most dangerous flash point when the Cuban Missile Crisis later unfolded in October 1962 as the emboldened Soviets, thinking Kennedy indecisive, tried to place missiles in Cuba.

In the view of many historians, the Bay of Pigs debacle also helped create the mind-set that sucked America into the mire of Vietnam. Having failed so completely in their attempt to rid Cuba of Communism, Kennedy and his advisers sought to counter the spread of Communism in Asia. And another fiasco began.

The Kennedy Library offers a page on the Bay of Pigs along with contemporary documents.

This post was adapted from Don't Know Much About History where you can read more about the impact of the Bay of Pigs on American policy and the Cold War era.

April 13, 2011

Don't Know Much About® Thomas Jefferson

Among America's iconic Founding Fathers, is there a more complicated and contradictory figure than Thomas Jefferson? Scientist, humanist, Enlightenment thinker, writer, architect, politician. He was all these things. The confusion over this genius comes from one basic question: How could the man who wrote, "All Men are Created Equal" and "Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness" go home to a Monticello plantation, completely dependent upon slave labor?

Even Jefferson's birthday is confusing. History books say he was born on April 13,1743. But the grave marker at Monticello says he was born on April 2. That one is easier to answer than some of the larger contradictions in Jefferson's life. Jefferson was born while the old Julian calendar was still in use in Protestant England and its American colonies. So the April 2 date is called "Old Style" (O.S.). When Great Britain and America finally came around and adopted the Gregorian (named for Pope Gregory) Calendar in 1758, Jefferson's birth date was changed to April 13.

Thomas Jefferson's Grave Marker at Monticello (Photo: Kenneth C. Davis, 2010)

Birth date aside, Thomas Jefferson is such a fascinating and confounding personality because he more than anyone embodies the "Great Contradiction" in American history. How could a nation dedicated to ideals of freedom and liberty continue a system that enslaved human beings in the cruelest of ways?

That contradiction is nowhere more evident than in Jefferson's original draft of Declaration of Independence.

A few years ago, at the New York Public Library, I had the thrilling experience of seeing Jefferson's handwritten copy of his original draft of the Declaration of Independence. We may take the words for granted now. But Jefferson gave full voice to the idea that we all possess "inalienable rights." That we are "created equal." That we have basic rights to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." That governments exist to advance those human rights, and only with the "consent of the governed."

This document was written on both sides of two pieces of paper. In his careful, flowing script, Jefferson included all of his original wording to show what the Congress in Philadelphia had changed, underscoring words and phrases that had been deleted. Those alterations, Jefferson, thought were "mutilations." Distressed by the editing, he made these "fair copies" of his original some time after July 4th. (The document held by the New York Public Library is one of only two known surviving copies.)

The most startling of these changes is a paragraph about what Jefferson calls "this execrable commerce" — slavery. Jefferson charged –rather ridiculously, of course– that King George III was responsible for the slave trade and was preventing American efforts to restrain that trade. The section was deleted completely. But it is striking to see Jefferson's bold, block lettering when he describes:

an open market where MEN should be bought & sold

He clearly wanted to underscore his belief that slaves were MEN. The contradiction is stunning, troubling, and difficult to resolve. Jefferson knew slavery was wrong. He believed, like fellow slaveholder George Washington, that it would end. But both men were inextricably tied to the slave society and economy, even though they believed that the "peculiar institution" would gradually die out. On that point, both men were grievously wrong and the 150th anniversary of the Civil War's opening on April 12 is a grim reminder of that.

Of course, part of the cynicism in Jefferson's case is due to the rumored relationship between Jefferson and slave Sally Hemings. Even Monticello now acknowledges that relationship probably existed, a contention first raised publicly in 1802 by muckraking newspaperman James Callender, a former Jefferson ally who was disgruntled when Jefferson did not offer him a post in the government. In recent years, Monticello has also gone a long way in addressing the question of slave life at the plantation.

Jefferson, who died on July 4, 1826 –the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration– and his deep contradictions are the perfect reminder that politicians are people –even the marble gods like Washington and Jefferson. Their all-too human flaws are proof of that as well as the fact that history books once tried to hide these flaws by pointing to the past with pride and patriotism.

Those flaws are explored in several of my books, including Don't Know Much About History, Don't Know Much About the Civil War and most recently A Nation Rising, in which I write about Jefferson's bitter relationship with his first Vice President, Aaron Burr, a man Thomas Jefferson tried to destroy using every political tool at his disposal as President.

I have always felt that seeing a man like Jefferson as human and not a demigod does not diminish his accomplishments as a leader, philosopher, champion of religious freedom and rationality and builder of a great university. If anything, those accomplishments become all the more remarkable.

April 5, 2011

Don't Know Much About® Poetic First Lines

"April," as T.S. Eliot told us, "is the cruellest month."

It is also National Poetry Month. That idea was inaugurated in 1996 by the Academy of American Poets. So to test your poetic wits, a quick Pop Quiz on some famous first poetic lines… Then go read the whole poems.

"Let us go then, you and I." With this opening line, T.S. Eliot invites his reader into the mind of his uninspired, indecisive narrator in "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock." A poem's first line can set a scene, as Walt Whitman's "When lilacs last in the dooryard bloomed" does. Or it might intrigue the reader, as when Emily Dickinson writes, "I heard a Fly buzz—when I died" (Poem 465).

Who opened their poems with the famous lines below? See how many poets you can identify.

1. How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

2. anyone lived in a pretty how town

3. Take up the White Man's burden–

4. 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

5. In Xanadu did Kubla Kahn

6. It so happens I am sick of being a man.

7. I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

This quiz is adapted from Don't Know Much About Literature

Answers

1. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "Sonnet 43."

2. e.e. cummings, "anyone lived in a pretty how town."

3. Rudyard Kipling, "The White Man's Burden." This 1899 poem encouraged Americans to colonize the Philippines and other former Spanish colonies.

4. Lewis Carroll, "Jabberwocky" from Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There.

5. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Kahn."

6. Pablo Neruda, "Walking Around" (trans. Robert Bly).

7. Allen Ginsberg, "Howl."

April 3, 2011

Don't Know Much About® the "Marshall Plan"

On April 3, 1948, President Truman signed into law the Foreign Assistance Act of 1948, otherwise known as The Marshall Plan, widely considered the most important foreign policy success of the postwar period.

On June 5, 1947, Secretary of State George C. Marshall gave Harvard's commencement address, introducing and justifying the European Recovery Program, which became known as the Marshall Plan. Marshall had been the Chief of Staff of the Army during World War II and Winston Churchill hailed him as the "true organizer of victory.". This plan, part of the Cold War program of "containment" championed by George F. Kennan, is credited with restoring the economies of post World War II western Europe.

At Harvard, Marshall said:

The truth of the matter is that Europe's requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential products—principally from America—are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help, or face economic, social and political deterioration of a very grave character.

…Aside from the demoralizing effect on the world at large and the possibilities of disturbances arising as a result of the desperation of the people concerned, the consequences to the economy of the United States should be apparent to all. It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.

Conceived by Undersecretary of State Will Clayton and first proposed by Secretary of State Dean Acheson (1893–1971), the Marshall Plan pumped more than $12 billion into selected war torn European countries during the next four years. (The countries participating were Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, West Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey.) It provided the economic side of Truman's policy of containment by removing the economic dislocation that might have fostered Communism in Western Europe. It also set up a Displaced Persons Plan under which some 300,000 Europeans, many of them Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, were granted American citizenship. By most accounts, the Marshall Plan was the most successful undertaking of the United States in the post-war era and is often cited as the most compelling argument in favor of foreign aid.

To some contemporary critics on the left, the Marshall Plan was not simply pure American altruism —the goodhearted generosity of America's best intentions. To them it was simply an extension of a capitalist plan for American economic domination, a calculated Cold War ploy to rebuild European capitalism. Or, to put it simply, if there was no Europe to sell to, who would buy all those products the American industrial machine was turning out?

By any measure, the Marshall Plan must be considered an enormously successful undertaking that helped return a devastated Europe to health. allowing free market democracies to flourish while Eastern Europe, hunkered down under repressive Soviet controlled regimes, stagnated socially and economically.

Marshall won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953. For more about Marshall, here is a link to the nonprofit Marshall Foundation:

Read more about World War II and the Cold War in Don't Know Much About® History

March 29, 2011

Don't Know Much About® "His Accidency," John Tyler

It is quite possible that all you know about the 10th President, John Tyler, is that he is the hind-part of a memorable campaign slogan: Tippecanoe and Tyler too!

John Tyler was born this day, March 29, in 1790, at Greenway, a James River plantation in Charles City County, Virginia, between Richmond and Williamsburg. The son of a wealthy planter and judge, he was raised among Virginia's elite, attending William and Mary College. He graduated at age 17 and then studied law, earning admission to the bar in 1809.

Tyler served in Congress in both the House and Senate, as well as the Virginia legislature, and in 1840 was named the running mate of William Henry Harrison, a fellow Virginian known as the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe –fought against a confederation of Native American nations led by Tecumseh in 1811.

"Tippecanoe and Tyler too" defeated the incumbent Martin Van Buren, and Harrison took the oath of office on March 4, 1841, delivering the longest inaugural speech in history. He then took ill and died of pneumonia on April 4, 1841, becoming the first President to die in office.

That made Tyler the first Vice-President to succeed to the office on the death of a President. The chief controversy of his early administration was over his legal status. Was Tyler actually the President or merely the "acting President?" He regarded himself as President and even returned mail unopened that was addressed to "The Acting President." But many derided him as His Accidency.

Another distinction was Tyler's marriage, following the death of his first wife Letitia Christian in 1842, to Julia Gardiner. The daughter of a wealthy New York politician, she had created a minor scandal in polite society by appearing in an advertisement at age 19. When they married in New York City in 1844, she was 24; Tyler was 54 and the 30-year age difference raised eyebrows and caused a rift with some of Tyler's grown children. However, this wedding earned Tyler the distinction of being the first President to be married while in office.

Sherwood Forest Virginia Home of President John Tyler (Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis, 2010)

His single term ended and he failed to be renominated. Tyler gave way to the the candidacy of James K. Polk rather than run as third-party candidate. Tyler retired to this plantation home, Sherwood Forest, which is a National Historic landmark in Virginia.

His final distinction was his election to the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy and his failed attempt to broker a peace deal before the Civil War broke out. But in November 1861, Tyler was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives, becoming the first former President to be elected to serve in another government –the Confederacy.

Tyler died on January 18, 1862 before taking his seat in the Confederate Congress. Although he had planned to be buried at his Sherwood Forest home, he is buried in Richmond.

For many years after the Civil War, his resting place was officially ignored. In 1915, 50 years after the Civil War ended, the Congress voted to erect a memorial stone over his grave.

March 26, 2011

Touch of Frost: A Videoblog

"I had a lover's quarrel with the world."

Robert Frost –born March 26, 1874.

One of my favorite spots in Vermont is the Frost gravesite in the cemetery of the First Church in Old Bennington -just down the street from the Bennington Monument.

Apples, birches, hayfields and stone walls; simple features like these make up the landscape of four-time Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Frost's poetry. Known as a poet of New England, Frost (1874-1963) spent much of his life working and wandering the woods and farmland of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire. As a young man, he dropped out of Dartmouth and then Harvard, then drifted from job to job: teacher, newspaper editor, cobbler. His poetry career took off during a three-year trip to England with his wife Elinor where Ezra Pound aided the young poet. Frost's language is plain and straightforward, his lines inspired by the laconic speech of his Yankee neighbors.

But while poems like "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" are accessible enough to make Frost a grammar-school favorite, his poetry is contemplative and sometimes dark—concerned with themes like growing old and facing death. Robert Frost –New England's poet of snowy woods, stone wall and apple trees.

I hope this "touch of Frost" will inspire you to read some of his work.

Here's a link to Robert Frost's page at Poets.org

http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/192

It includes an account of Frost and JFK

http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/20540

The first poet invited to speak at a Presidential inaugural, Frost told the new President:

"Be more Irish than Harvard. Poetry and power is the formula for another Augustan Age. Don't be afraid of power."

Hear Robert Frost for yourself at Poets Out Loud:

http://robertfrostoutloud.com

This link is to Middlebury College's online Frost exhibit

http://midddigital.middlebury.edu/local_files/robert_frost/index.html

This is the website of Frost House and Museum in Franconia, N.H. http://www.frostplace.org/html/museum.html

Robert Frost died on January 29, 1963. He had written his own epitaph, "I had a lover's quarrel with the world," etched on his headstone in a church cemetery in Bennington, VT.

Here is the NYTimes obituary published after his death.

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0129.html#article

This material is adapted from Don't Know Much About Literature written in collaboration with Jenny Davis.

March 23, 2011

Don't Know Much About® Internment

It was on March 23, 1775 that Patrick Henry offered his famous "Give me liberty or give me death" speech in colonial Virgina.

On Mach 23, 1942 –167 years later– the United States government began taking away the liberty of more than one hundred thousand people–the Japanese Americans viewed as a threat after Pearl Harbor. On that date, the U.S. Army began removing people of Japanese descent from Los Angeles.

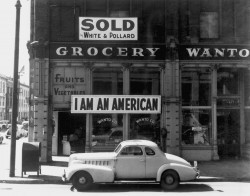

Photo by Dorothea Lange of Japanese-American grocery store on the day after Pearl Harbor Source: Library of Congress

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan, there was a wave of fear and hysteria aimed at Japanese and people of Japanese descent living in America, including American citizens, mostly on the West Coast. In February 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which declared certain areas to be "exclusion zones" from which the military could remove anyone for security reasons. It provided the legal groundwork for the eventual relocation of approximately 120,000 people to a variety of detention centers around the country, the largest forced relocation in American history. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens. (Smaller numbers of Americans of German and Italian descent were also detained.)

Photo Source: National Archives

The attitude of many Americans at the time was expressed in a Los Angeles Times editorial of the period:

"A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched… So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere… notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American…" (Source: Impounded, p. 53)

There were several types of camps run by the government but the most notable, including Manzanar, were the "Relocation Centers" run by the War Relocation Authority. The camps were located in remote often desolate areas, some on lands purchased from Native American nations. Surrounded by barbed wire, they featured tar paper shacks with no toilets or cooking facilities."Spartan" would be a kind description.

In 1943, the Army invited Japanese Americans to enlist, and during the war, 30,000 Japanese Americans volunteered to serve in the U.S. military. (Source: National Archives)

The exclusion order was rescinded in 1945 and internees were allowed to leave, although many had lost their homes, businesses and property during their confinement. However, the last camp did not close until 1946.

In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate the internment and, in 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which provided for a reparation of $20,000 to surviving detainees.

One of those detainees was Albert Kurihara who told the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981:

"I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget." (from Impounded, Norton)

The National Parks Service offers a Teaching With Historic Places lesson plan based on the camps some of which are now part of the National Parks System including Minidoka in Idaho and the Manzanar camp in California.

Archival Research Gallery (National Archives) of Japanese-American Experience

Library of Congress Collection of Ansel Adams photographs of internment camp at Manzanar

Photographer Dorothea Lange also photographed the internment camps and her censored images were published in 2006 in the book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (WW Norton, 2006).

March 16, 2011

Don't Know Much About Mr. Madison

Today March 16, 2011, marks the 260th anniversary of the birth of America's fourth President, James Madison, also known as "The Father of the Constitution."

While small in stature, and sometimes overshadowed by his more famous Virginian predecessors, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, Madison must be considered one of the greatest of the Founding Fathers for the breadth and influence of his contributions.

Montpelier, home of James Madison (Photo: Kenneth C. Davis, 2010)

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751 in Port Conway, Virginia. The son of a tobacco planter, he was somewhat sickly as a child and was mostly tutored at home. But he proved to be a true scholar and at age 16, chose the unusual course –at that time– of going north to study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), rather than the College of William and Mary in nearby Williamsburg. There he came under the influence of the college President, John Witherspoon, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence, and made a friend of fellow student, young Aaron Burr, son of the College's founder.

Returning to Virginia, Madison became involved in patriot politics and became a close colleague of his neighbor Thomas Jefferson, serving as Jefferson's adviser and confidant during the war years while Jefferson was Governor of Virginia.

In 1794, he married the widow Dolley Payne Todd, having been formally introduced by his college friend Aaron Burr.

A few Madison Highlights–

•Secured passage of the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786), an act that is a cornerstone of religious freedom in America. As part of that effort, he wrote the influential Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments. (I discuss the "Remonstrance" in my article "America's True History of Religious Tolerance" in the October 2010 Smithsonian.)

•Was the moving force behind the Constitutional Convention and was one of the principal authors of the Constitution

•With Alexander Hamilton and John Jay was one of the authors of The Federalist Papers, arguments in favor of the ratification of the Constitution

•Was principal author of the Bill of Rights, which he originally thought unnecessary

Following ratification of the Constitution, Madison was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia and a powerful Congressional ally of George Washington.

•Drafted the first version of Washington's Farewell Address

•Supervised the Louisiana Purchase as Thomas Jefferson's Secretary of State

•Presided over the ill-prepared nation during the War of 1812, the "second war of independence"

I believe there are more instances of the abridgment of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments of those in power than by violent and sudden usurpations. –June 16, 1788

Madison died on June 28, 1836 at Montpelier, at age 85. He is buried at Montpelier.

LINKS:

The White House brief biography of James Madison

The Library of Congress Resource Collection on James Madison.

Madison's Major Papers and Inaugural Addresses can be found at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School.