Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 111

June 15, 2011

Don't Know Much About History… Still!

That headline in yesterdays's AP story gave me no pleasure. The latest in the perennial drumbeat of bad news about failing American History grades in American schools has just been released. And it is as bad as ever.

We seem to be no better off now than we were back in 1987 when the first major survey was called "What Our 17 Year Olds Know." (It would have been more appropriately entitled "What they don't know.")

So the first simple question is:

Why Are we so Bad at History?

There has been an assumption that we all hate history, probably because all the surveys keep telling us that. But the simple fact is that people really don't hate history. They just hate the dull, watered-down version they were forced to learn in school. And that is Reason #1 that we don't know much about History.

Reason #2 is an old problem that has gotten worse. We don't spend enough time teaching history. That problem has worsened over the past few years, according to history teachers I speak with, because of No Child Left Behind. History teachers often tell me that they are pulled away from their regular curriculum to assist in standardized test preparation in math and reading because judging school performance and funding for schools has been reduced to how well children do on these tests. And yes, far too many teachers have come into the system without sufficient understanding of history and its importance.

Reason #3 is the media –both news and entertainment. There is still tremendous distortion of history in the daily news –some of it deliberate by people with agendas. Then there is the problem of Hollywood History. There are millions of children who think that Pocahontas was a buxom Disney character in a tight, deerskin skirt.

What Can We Do?

The solution to this epidemic of historical ignorance is fairly simple.

•If we think history is so important, spend more time actually teaching it.

•Throw out the textbooks. Okay, maybe not actually. But I don't know any teachers or students who enjoy textbooks. History is first and foremost STORY. Tell great stories of real people doing real things. We are in a golden age of great historical writers who know how to tell stories. Use them in the classroom. I have seen kids in elementary school who show total curiosity and enthusiasm about history. By high school, that excitement is sucked out of them by rote learning and dishwater dull textbooks.

•Field trips. I know. You shudder at the thought of brown bags and bus rides. But going to the places where history happens makes all the difference in the world. My love of history came from camping trips to places like Gettysburg, Valley Forge and Fort Ticonderoga. And you don't have to be near Boston, Washington, D.C. or Philadelphia to see history. It is everywhere.

•Stop lying. Museums and historic sites have to tell the truth, not a sanitized, cosmetically perfect version. In Florida, a recreated Spanish village tells visitors that the French were "banished" from Florida by the Spanish in 1565. That's just not true. They were massacred in a religious bloodbath. Now that is an interesting story. Places like Monticello and Mount Vernon, on the other hand, have come light years from the stodgy museums they once were. They are exciting but more important honest. Both openly deal with the question of slavery in realistic and vivid terms. They don't try and hide the truth that Jefferson and Washington were slaveholders.

•Use the media. There are some great movies about history, like Glory. Use them to teach. There are many more awful movies about history. We can use them too, by watching and saying "This is not the way it happened." The real story of Pocahontas is a lot more interesting than the Disney cartoon version. Use that –don't run away from it.

•Cross-pollinate. By this I mean what the academics like to call "interdisciplinary approach." Teaching American colonial history? Make sure the English teacher is having the class read The Crucible. Then you can talk about the real Salem Witch Trials –who isn't interested in witches?– as well as the McCarthy Era which inspired Arthur Miller to write the play.

These are just a few of the lessons I've learned about getting people interested in History. So the secret to this success was simple: "If you build it, they will come." Just tell people about history in a way that is lively, meaningful, fun, relevant and most important, human, and they will listen. Work with curiosity instead of destroying it with myths, lies and tedium. Make it fun. But mostly make it real.

June 10, 2011

"Palin and the Truth About Paul Revere" (CNN.com)

"Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, / On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five, / Hardly a man is now alive / Who remembers that famous day and year."

"If nothing else is right about Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem, first published more than 85 years after that legendary ride, the part about not remembering the day and year rings true.

Since Sarah Palin's impromptu discourse on Paul Revere, there has been much discussion of her account. She referred to the famed horseman as, "He who warned the British that they weren't going to be taking away our arms by ringing those bells and making sure as he's riding his horse through town to send those warning shots and bells that we were going to be secure and we were going to be free."

Her words provoked an awful lot of hysteria, but not enough history, about this signal event."

Read the rest of this article about Revere's Ride, Palin's version and the uses of American History at CNN.com Opinion

June 9, 2011

"Beam me IN, Scotty" –Library Visits with Author Kenneth C. Davis

AN OPEN LETTER TO LIBRARIANS—

"BEAM ME IN, SCOTTY!"

Apologies to Captain Kirk and Star Trek. I know it's really, "Beam me UP, Scotty."

For more than 20 years, I have been traveling the country to visit libraries, bookstores, museums, schools and librarian conferences to share my love for history, geography and all the subjects I have covered in the Don't Know Much About series of books for children and adults. It's always great fun for me to talk about America's past, telling real stories of real people, exploring the "hidden history" I've uncovered, connecting history to the headlines –and sharing my love for writing and books. Our teachers and librarians are dedicated professionals. And the readers I have met over those years have proven that Americans don't hate history. They just hate the dull version they got in school. And this writer has learned a lot from them along the way.

Now, with the power of computers, I want to visit your library virtually. Will you invite me?

Before I tell you my plan, I want you know that libraries have a great personal value to me. When I was a boy growing up in Mount Vernon, New York, a trip to the library every few days was part of my life. I remember the day I got my "adult" library card which allowed me to climb the ornate marble stairs up to the second floor main stacks. For me, the library was a central part of my education — and my love of writing. Since then, I have always believed that libraries are an essential part of our democracy. It would be nice if every government office functioned as well as the library does!

Now, on to my plan.

As we are marking the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, which began on April 12, 1865, I will make a limited number of FREE library Skype visits to discuss Civil War history, the life of Abraham Lincoln, and other aspects of this momentous tragedy in our past and how it continues to haunt us. These visits are planned to last 30-40 minutes. They will include a brief introduction by me of my work and career and a discussion of some of the major aspects of the Civil War, and time for audience questions –always my favorite part of the visit. While the Civil War is certainly the key subject, the discussion need not be limited to that piece of American History. As a newly revised and updated edition of my New York Times Bestseller Don't Know Much About History is being published this month in an Anniversary Edition hardcover by HarperCollins, the floor will be wide open for all questions about American History, the headlines, or books and writing in general.

If you would like to organize a library event on your end and "Beam me IN, Scotty," via Skype, a video link to your library computers, please use the Contact page on my website. We will get back to you in an effort to set up a convenient time and date.

I look forward to beaming into your library!

Best wishes,

Kenneth C. Davis

May 26, 2011

Don't Know Much About® Internment

(In honor of Dorothea Lange's birthday on May 26, 1895, I am re-posting this recent piece about the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, the subject of some of her most important photographs.)

It was on March 23, 1775 that Patrick Henry offered his famous "Give me liberty or give me death" speech in colonial Virgina.

On Mach 23, 1942 –167 years later– the United States government began taking away the liberty of more than one hundred thousand people–the Japanese Americans viewed as a threat after Pearl Harbor. On that date, the U.S. Army began removing people of Japanese descent from Los Angeles.

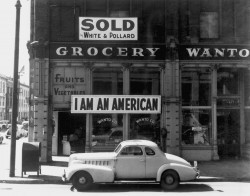

Photo by Dorothea Lange of Japanese-American grocery store on the day after Pearl Harbor Source: Library of Congress

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan, there was a wave of fear and hysteria aimed at Japanese and people of Japanese descent living in America, including American citizens, mostly on the West Coast. In February 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which declared certain areas to be "exclusion zones" from which the military could remove anyone for security reasons. It provided the legal groundwork for the eventual relocation of approximately 120,000 people to a variety of detention centers around the country, the largest forced relocation in American history. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens. (Smaller numbers of Americans of German and Italian descent were also detained.)

Photo Source: National Archives

The attitude of many Americans at the time was expressed in a Los Angeles Times editorial of the period:

"A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched… So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere… notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American…" (Source: Impounded, p. 53)

There were several types of camps run by the government but the most notable, including Manzanar, were the "Relocation Centers" run by the War Relocation Authority. The camps were located in remote often desolate areas, some on lands purchased from Native American nations. Surrounded by barbed wire, they featured tar paper shacks with no toilets or cooking facilities."Spartan" would be a kind description.

In 1943, the Army invited Japanese Americans to enlist, and during the war, 30,000 Japanese Americans volunteered to serve in the U.S. military. (Source: National Archives)

The exclusion order was rescinded in 1945 and internees were allowed to leave, although many had lost their homes, businesses and property during their confinement. However, the last camp did not close until 1946.

In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate the internment and, in 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which provided for a reparation of $20,000 to surviving detainees.

One of those detainees was Albert Kurihara who told the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981:

"I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget." (from Impounded, Norton)

The National Parks Service offers a Teaching With Historic Places lesson plan based on the camps some of which are now part of the National Parks System including Minidoka in Idaho and the Manzanar camp in California.

Archival Research Gallery (National Archives) of Japanese-American Experience

Library of Congress Collection of Ansel Adams photographs of internment camp at Manzanar

Photographer Dorothea Lange also photographed the internment camps and her censored images were published in 2006 in the book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (WW Norton, 2006).

May 18, 2011

The Bible Riots of 1844 (DKMA Minute #18)

In May 1844, Philadelphia –the City of Brotherly Love– was torn apart by a series of bloody riots. Known as the "Bible Riots," they grew out of the vicious anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment that was so widespread in 19th century America. Families were burned out of their homes. Churches were destroyed. And more than two dozen people died in one of the worst urban riots in American History.

The story of the "Bible Riots" is another untold tale that I explore in my new book A NATION RISING available in paperback in June 2011

May 17, 2011

Don't Know Much About® "Brown v. Board of Education"

Every day, eight-year-old Linda Brown wondered why she had to ride five miles to school when her bus passed the perfectly lovely Sumner Elementary School, just four blocks from her home. When her father tried to enroll her in Sumner for fourth grade, the Topeka, Kansas, school authorities just said no. In 1951, Linda Brown was the wrong color for Sumner.

In 1951, the law of the land remained "separate but equal," the policy dictated by the Supreme Court's 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. "Separate but equal" kept Linda Brown out of the nearby Topeka schoolhouse and dictated that many public facilities, from maternity wards to morgues, from water fountains to swimming pools, from prisons to polling places, were either segregated or for whites only.

Exactly how these "separate" facilities were "equal" remained a mystery to blacks: If everything was so equal, why didn't white people want to use them? Nowhere was the disparity more complete and disgraceful than in the public schools, primarily but not exclusively in the heartland of the former Confederacy. Schools for whites were spanking new, well maintained, properly staffed, and amply supplied. Black schools were usually single-room shacks with no toilets, a single teacher, and a broken chalkboard.

If black parents wanted their children to be warm in the winter, they had to buy their own coal. But a handful of courageous southern blacks—mostly common people like teachers and ministers and their families—began the struggle that turned back these laws.

Urged on by Thurgood Marshall (1908–93), the burly, barb tongued attorney from Baltimore who led the NAACP's Legal Defense and Educational Fund, small-town folks in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware balked at the injustice of "separate but equal" educational systems. The people who carried these fights were soon confronted by threats ranging from loss of their jobs to dried-up bank credit and ultimately to threats of violence and death.

In 1951, one of these men was the Reverend Oliver Brown, the father of Linda Brown, who tried to enroll his daughter in the all-white Topeka school. Since Brown came first in the alphabet among the suits brought against four different states, it was his name that was attached to the case that Thurgood Marshall argued before the Supreme Court in 1953.

There had been a change in the makeup of the Court itself. After the arguments in Brown v. Board of Education were first heard, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, a Truman appointee, died of a heart attack. In 1953, with reargument of the case on the horizon, President Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren (1891–1974) chief justice of the United States.

Certainly nobody at the time suspected that Warren would go on to lead the Court for sixteen of its most turbulent years, during which the justices took the lead in transforming America's approach to racial equality, criminal justice, and freedom of expression.

In the Brown case, Warren led the Court to a moment of needed unanimity. The decision was announced on May 17, 1954. As the New York Times banner headine proclaimed, "High Court Bans School Segregation"

"Separate but equal" was no longer the law of the land.

In Simple Justice, a monumental study of the case and the history of racism, cruelty, and discrimination that preceded it, Richard Kluger eloquently assessed the decision's impact:

The opinion of the Court said that the United States stood for something more than material abundance, still moved to an inner spirit, however deeply it had been submerged by fear and envy and mindless hate. . . . The Court had restored to the American people a measure of the humanity that had been drained away in their climb to worldwide supremacy. The Court said, without using the words, that when you stepped on a black man, he hurt. The time had come to stop.

Of course, Brown did not cause the scales to fall from the eyes of white supremacists. The fury of the South was quick and sure. School systems around the country, South and North, had to be dragged kicking and screaming through the courts toward desegregation. The states fought the decision with endless appeals and other delaying tactics, the calling out of troops, and ultimately violence and a venomous outflow of racial hatred, targeted at schoolchildren who simply wanted to learn.

This material is adapted from Don't Know Much About® History which will be reissued on June 21, 2011 in a newly revised, updated and expanded 20th Anniversary Edition.

May 9, 2011

Don't Know Much About® John Brown

Abolitionist martyr? Or terrorist? Born on May 9, 1800, John Brown has always posed that awkward question in American history.

I am quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.

–John Brown at his execution (November 2, 1859)

Viewed through history as a lunatic, psychotic, fanatic, visionary, and martyr, Brown came from a New England abolitionist family, several of whom were quite insane. A failure in most of his undertakings, he had gone to Kansas –then in the midst of a mini Civil War over slavery– in 1855 with five of his twenty-two children to fight for the antislavery cause, and gained notoriety for an attack that left five pro-slavery settlers hacked to pieces.

After that massacre at Pottawatomie,Kansas, Brown went into hiding, but he had cultivated wealthy New England friends who believed in his violent rhetoric. A group known as the Secret Six formed to fund Brown's audacious plan to march south, arm the slaves who would flock to his crusade, and establish a black republic in the Appalachians to wage war against the slaveholding South. Brown may have been crazy, but he was not without a sense of humor. When President Buchanan put a price of $250 on his head, Brown responded with a bounty of $20.50 on Buchanan's.

Among the people Brown confided in was Frederick Douglass; Brown saw Douglass as the man slaves would flock to, a "hive for the bees." But the country's most famous abolitionist attempted to dissuade Brown, not because he disagreed with violence but because he thought Brown's chosen target was suicidal. Few volunteers answered Brown's call to arms, although Harriet Tubman signed on with Brown's little band. She fell sick, however, and was unable to join the raid.

On October 16, 1859, Brown, with three of his sons and fifteen followers, white and black, attacked the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, on the Potomac River not far from Washington, D.C. Taking several hostages, including one descendant of George Washington, Brown's brigade occupied the arsenal. But no slaves came forward to join them. The local militia was able to bottle Brown up inside the building until federal marines under Colonel Robert E. Lee and J. E. B. Stuart arrived and captured Brown and the eight men who had survived the assault.

Within six weeks Brown was indicted, tried, convicted, and hanged by the state of Virginia, with the full approval of President Buchanan. But during the period of his captivity and trial, this wild-eyed fanatic underwent a transformation of sorts, becoming a forceful and eloquent spokesman for the cause of abolition.

While disavowing violence and condemning Brown, many in the North came to the conclusion that he was a martyr in a just cause. Even peaceable abolitionists who eschewed violence, such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, overlooked Brown's homicidal tendencies and glorified him. Thoreau likened Brown to Christ; Emerson wrote that Brown's hanging would "make the gallows as glorious as the cross."

The view in the South, of course, was far different. Fear of slave insurrection still ran deep. To southern minds, John Brown represented Yankee interference in their way of life taken to its extreme. Even conciliatory voices in the South turned furious in the face of the seeming beatification of Brown. When northerners began to glorify Brown while disavowing his tactics, it was one more blow forcing the wedge deeper and deeper between North and South.

This material is adapted from Don't Know Much About History. More information about Brown and his role in the conflict that led to the Civil War can be found in Don't Know Much About the Civil War.

Revised, updated and expanded edition scheduled for release in June 2011.

The paperback edition has been released with a new cover to mark the 150th anniversary of the Civil war.

DKMA Minute-A Nation Rising: A Video Q&A with Author Kenneth C. Davis

With the publication of A NATION RISING (Smithsonian/HarperCollins) on May 11th, bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis answers some questions about his career and new book.

JUST IN: Advance Praise for A NATION RISING:

Davis is a fine writer who uses a fast-moving narrative to tell these stories well.

–Jay Freeman, Booklist (May)

Advance Praise for A NATION RISING–

"With his special gift for revealing the significance of neglected historical characters, Kenneth Davis creates a multilayered, haunting narrative. Peeling back the veneer of self-serving nineteenth-century patriotism, Davis evokes the raw and violent spirit not just of an 'expanding nation,' but of an emerging and aggressive empire."

-Ray Raphael, author of Founders

May 4, 2011

Teachers–Join the Conversation

On Tuesday May 17 at 4 PM (Eastern Time), I will be participating in my first webinar via the National Council for the Social Studies. Register here

"Bestselling author Ken Davis invites teachers to join in an interactive discussion about teaching American History in more exciting ways. Davis, known for his down-to-earth, non-academic style, will present a brief introduction on what excites him in his study of American History, and what he's learned in twenty years of talking to Americans about what they "need to know about American History." Then he will open up the webinar to questions and comments from teachers.

"This is not a lecture, but a dialog," says Davis, who hopes you will join the session and share your ideas and experiences about what works in the classroom."

April 28, 2011

Happy Birthday, Harper Lee

Born April 28, 1926 in Monroeville, Alabama –Nelle Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird.

If you only publish one book, may as well make it a good one. For Harper Lee it was To Kill A Mockingbird (1960), the story of Scout Finch, a girl growing up in a small Southern town. Scout and her brother Jem wake up to the intolerance and racial hatred around them when their father, Atticus, takes on the legal case of a black man accused of raping a white woman. To Kill a Mockingbird won the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, and in the last ten years, it has been far and away the most popular selection for "One Book, One Community" reading programs—for example, every Vermont resident was encouraged to read the novel in 2011. Do you know why it's a sin to kill a mockingbird? Take this quick quiz on the beloved coming-of-age novel (adapted from Don't Know Much About Literature, a collection of literary quizzes.)

1. In what fictional town is To Kill A Mockingbird set?

2. In which real Alabama town were nine black teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931?

3. Which character in To Kill a Mockingbird did Lee base on her childhood friend Truman Capote?

4. What is the name of Scout's reclusive neighbor, whom she begins to understand better at the end of the novel?

5. Who won an Oscar for his role as Atticus Finch in the 1962 film version of the novel?

Answers

1. Maycomb, Alabama.

2. Scottsboro. The case of the "Scottsboro Boys" provided real-life inspiration for Lee's novel.

3. Dill Harris, Scout Finch's friend and neighbor. Lee was the prototype for one of Capote's characters: Idabel Tompkins in Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948).

4. Boo Radley.

5. Gregory Peck. Another of Peck's great roles from literature was in the 1956 film Moby Dick; he played Captain Ahab.

And by the way, it is a sin to kill a mockingbird because all they do is "make music for us to enjoy."