Rod Dreher's Blog, page 147

May 9, 2020

Weird Christianity: The Rod Dreher Interview

Tara Isabella Burton interviewed me by email back in November for the piece that runs in today’s NYT Opinion section. It’s about “Weird Christianity”. Here are her questions and my answers:

Do you think we’re seeing a rise in “Weird” (aka countercultural, aesthetically/liturgically traditional) Christianity? Why — and what might be the source of its appeal?

Yes, but my sense is that it’s small and hard to quantify. If you only go by Twitter, you’d think that the Millennial Catholic world was crawling with integralists. But really, how many are there? Similarly, at my small Orthodox mission parish in Baton Rouge, we’re seeing more and more converts, almost all men and women in their twenties or early thirties — all former Evangelicals who came to us craving depth and liturgical beauty. This is fantastic, but at this point, it’s only a trickle.

Nevertheless, it’s there. What is the source of its appeal? Let me think about what drew me to it as a young man. When I was around 14 or 15, I got rid of the Christianity in which I was raised. My folks were the kind of Methodists who went to church on Easter and Christmas, and every now and then throughout the year. Our Christianity was cultural, in the sense that Kierkegaard said in his ‘Attack Upon Christendom’. I forget his exact quote, but he basically said that when people are counted as Christian simply by virtue of having been born into a Christian society, then Christianity effectively ceases to exist. His point was that Christianity made constant demands on the believer — that it was something radical, that it required constant conversion. It would be a few years before I read Kierkegaard, but when I finally encountered him as a college student, I recognized the Christianity that I had left behind for agnosticism.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. As a teenager in the 1980s, I thought Christianity was either the boring middle class at prayer, or it was Jimmy Swaggart’s hellfire Pentecostalism. Neither one spoke to me. It wasn’t until I stumbled into the Chartres cathedral at age 17, on a tour group, that I was confronted by a form of Christianity that overwhelmed me. Nothing in my life in small-town America in the late 20th century had prepared me for the grandeur of God made manifest in that Gothic cathedral. What kind of Christianity inspires men to build this kind of temple? That was probably the first time in my life that I was truly struck by awe, in the old-fashioned sense. I remember standing there, in the center of the labyrinth, looking all around at the stained-glass windows, the arches, and the vaults, thinking, “God does exist — and He wants me.”

I didn’t walk out of that cathedral as a Christian, but I did leave on a search. I read Thomas Merton’s “The Seven Storey Mountain,” which knocked me flat. I saw a lot of myself in pre-conversion Merton — an intellectually curious, slightly louche aesthete — and, along with him, I was completely seduced by the austere, mystical Catholicism he found in Trappist monasticism. It was so radically different from anything I had encountered, or imagined. Eventually I converted to Catholicism, and quickly learned how badly dated Merton’s book was. He wrote it in the 1940s. The Catholic Church that won over young Thomas Merton in fact barely existed anymore.

Of course from a strictly theological perspective, the Catholic Church was, and is, one and the same. But from an experiential point of view, contemporary Catholicism is a lot like contemporary Protestantism. That was a hard thing to get used to, but I did it. A decade after my conversion, I was living in New York and working for National Review. I was covering the Catholic abuse scandal, and just reeling from it all. My wife and I paid a visit to friends in suburban Maryland, the Orthodox Christian writer Frederica Mathewes-Green and her husband, a priest named Father Gregory. We attended the first half hour of the Divine Liturgy at their parish. It was so incredibly rich, aesthetically and spiritually. I remember thinking that this is what I thought I was converting to in Catholicism.

After a short while, though, we had to leave to go up the road to the Catholic parish to satisfy our Sunday obligation. We arrived at some early Seventies church that looked like Our Lady of Pizza Hut. We took our place in the pews, and, having just left an Orthodox parish, with colorful icons covering the walls, long tapered candles burning, and clouds of incense wafting high in the rafters, I was struck cold by the utter bareness of the place. It wasn’t the kind of plainness that conveys spiritual power and depth, as I’ve seen in some Catholic monastic chapels, but rather the absence of something. It reminded me of a dollar store at the end of a going out of business sale. The mass — all altar girls, by the way — was so puny and half-hearted. The elderly priest was delivering his final sermon before retirement, and all he could talk about was how much he looked forward to kicking back in Florida.

We left after the homily to go back to the Orthodox parish. My wife and I both had tears in our eyes. I started to speak, but she said, “Don’t say it.” I didn’t say anything. Three years later, having relocated to Dallas, both of us crushed by the abuse scandal and the total loss of trust in Catholic authority, we took refuge in the Orthodox cathedral there. We were so raw and broken that neither of us knew if we would ever be able to trust the institutional church again. But we knew at least we could rest in the beauty and richness of the liturgy and the church interior itself. After a year, we converted, and never looked back.

There is a very American moralistic distrust of aesthetic beauty and ritual in worship. You see it even among Catholics, who ought to know better. We seem to have a suspicion that you can either have moral rigor and doctrinal seriousness, or you can have beauty, but not both. When you go to church in Europe, though, you discover how stupid that is. Of course all that beauty is going unseen and unloved by the masses that don’t go to church, so we have to be careful not to over-emphasize beauty. But Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Benedict XVI, said that best argument the Church has for the Christian faith is its saints and its art. His point was that goodness incarnate (the saints) and incarnate beauty (sacred art, music, and architecture) open the door for truth. That’s certainly what happened to me. I was incapable of taking seriously apologetic arguments for the Christian faith, but the majesty of Gothic cathedral architecture dramatically challenged my intellectual resistance to Christianity.

And so I think this is why a certain kind of person really is drawn to the older, ritualistic, aesthetic forms of Christian worship. It speaks to something deep inside us, and, I think, it is a kind of rebellion against the ugliness and barrenness of modernity, especially within the churches. Plus, an expression of Christianity that appeals to our whole body, and all our senses, not just to our head, and our abstract reason — that’s really powerful. I’ve been Orthodox for as long as I was Catholic — 13 years — and I’ve been struck too by how attractive Orthodoxy is to men. I finally figured out that unlike most Western churches, Orthodoxy emphasizes self-overcoming, with a strong emphasis on asceticism. Expecting people to master their passions, and learning to do so through ascetic exercises like fasting — you can’t imagine how liberating that is when contrasted to therapeutic Western modes of religion, which so often emphasize feminine traits and modes of expression. Don’t get me wrong — Orthodoxy is not “masculinist.” But it seems to me that it’s more balanced, and it gives men something to do, not just feel.

I have to say, though, that in America, I wonder about the class implications of all this. Here’s what I mean. If you are going to become an Orthodox Christian, or a liturgically traditional Catholic, you are probably going to be the kind of person who is a strong seeker, and willing to be thought weird for the sake of finding God. Ancient Christian weirdness is acceptable, somehow, to intellectuals and aesthetes, in a way that low-church Protestant weirdness is not. I’ve been at monasteries where I’ve kissed the skull of a long-dead Orthodox elder, and I’ve thrown wax facsimiles of body parts onto the bonfire outside of the Portuguese basilica at the Fatima apparition site. Most people outside my Orthodox and Catholic circles would find that sort of thing to be high-octane crackpottery. But you know what I would never, ever do? Go to a Pentecostal megachurch and raise my hands high in the air. I don’t look down on those who do — it’s just unthinkable for me. Way, way too weird. It kind of embarrasses me to admit this, but Christians like me prefer our religious self-marginalization to be, I don’t know, literary. So I think we have to be aware that there might be some snob appeal in all this. I don’t think it is a significant factor at all — taking the old religion straight, and espousing its reactionary social beliefs, as one must if one is not merely an aesthete playing church, is no way to advance socially. Still, I think for some of us, we have to be careful about a temptation to a particular sort of spiritual pride. Oh Lord, I thank Thee for making me a pious weirdo, but not like those fundagelicals.

That said, there is just so much depth and beauty in ancient liturgical Christianity that you feel that you could never touch bottom. It’s like being in the Burning Bush — you are on fire, but never consumed. In Orthodoxy, priests are always referencing the early church fathers in their homilies. Not only am I often amazed by the wisdom and poetry of these saints, but I love that in the Orthodox church, in the ritual prayers, in the icons on the wall, and in the homilies, the memory of 2,000 years of Christian life and worship is kept front to mind. This is true whether you are a professor or a peasant. That continuity is also a great blessing of Orthodox worship, in this world of constant flux. There’s a joke Orthodox people tell:

Q: How many Orthodox Christians does it take to change a light bulb?

A: [heavy Slavic accent] Change? What is this ‘change’?

But it’s true! While everybody else is setting up smoke machines and strobe lights, or rewriting their hymns one more time to be ‘relevant,’ Orthodox priests are swinging the censers like they’ve done for many centuries, and the choirs are singing the same hymns that have been passed down for many, many generations. That is so comforting. It’s such a relief to not have to remake things in every generation, simply to receive what has been preserved for you. It’s a very un-modern, un-American thing, and that’s what makes it so attractive. I hasten to add that it’s not that Orthodox believers are holier than any other believer, but it’s that the Orthodox tradition, both liturgically and spiritually, has given us a reliable map and proven tools to help us along the pilgrim road to unity with Christ. Why would we not use them?

Do you think Christianity must always be countercultural — does it lose something if it allies too closely with the dominant culture?

Yes, I do. For one, Jesus said that His kingdom was not of this world. We desire to be subjects of the Lord’s kingdom. That means that there will always be some tension between us and the world. If Christianity teaches anything, it’s that this is not our home, that man is a wayfarer here. If you don’t feel uncomfortable in the world as a believer, then you’re missing something.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer said that when Christ calls a man, he bids him to come and die. And Bonhoeffer did die at the hands of the Nazis! I’ve spent a good part of this year traveling in Russia and the Soviet bloc countries, interviewing Christians who endured communist persecution. It’s incredibly humbling to be in the presence of people who suffered — some of them tortured in the gulag — for their faith. It makes you realize too how very, very easy we have it. I sat in the lobby of the Hotel Metropol in Moscow in early November, listening to Alexander Ogorodnikov, one of the most famous Christian dissidents of the late Soviet period, talk about preparing fellow inmates for execution. His face is partially paralyzed from the beatings he suffered in prison. He fought back tears as he spoke. And to think how afraid so many of us middle-class American Christians are that people at the office will think bad things about us! The world is too much with us, that’s for sure. I believe that persecution is coming, and that most of us American Christians will fall away, because we won’t be able to withstand losing our social status and material comforts. We have become totally assimilated.

I do have a bit of suspicion about Christians who are too conscious of being countercultural. It can be a kind of performance. There’s a certain kind of young Christian who thinks he’s defying convention by getting a tattoo, or some other totally bourgeois form of rebellion, but he would never be caught dead praying in front of an abortion clinic. I recognize some of this in myself, which is why I try to be suspicious of my own outsider-ness within the larger Christian fold. When I was in Russia recently, I interviewed an Orthodox priest who tends to a national shrine and monument on a site where the NKVD executed 21,000 people in a 14-month period, during the Terror. He told me that the real heroes of faith in the Soviet Union were the scarf-wearing babushkas who continued going to church, no matter what. Some of them were illiterate, but they were humble and they were fearless. And, he said, they saved Christianity in Russia.

Are Christian “values” in decline in the USA? What does that phrase — Christian values — even mean to you?

.

Yes, they are. The phrase “Christian values” has been worn as smooth as an old penny by overuse, especially in the mouths of political preachers. Look, I’m a theological, cultural, and political conservative, but I admit that it has become hard, almost impossible, to find the language to talk meaningfully about what it means to believe and act as a Christian. This is not a Trump-era thing; Walker Percy was lamenting the same thing forty years ago, at least. I think the term “Christian values” has become meaningless. It is taken as shorthand for opposing the Sexual Revolution, and all it entails — abortion, sexual permissiveness, gay marriage, and so forth. Don’t get me wrong, I believe that to be a faithful Christian does require one to oppose the Sexual Revolution, primarily because the Sexual Revolution offers a radically anti-Christian anthropology. But then, so does modernity — and this is an anti-Christian anthropology that clashes with the historic faith in all kinds of ways. I’m thinking of the way we relate to technology and to the economy.

You want to clear a room of Christians, both liberal and conservative? Tell them that giving smartphones with Internet access to their kids is one of the worst things you can do from the standpoint of living by Christian values. Oh, nobody wants to hear that! But it’s true — and it’s not true because this or that verse in the Bible says so. It’s true because of the narrative that comes embedded in that particular technology. It’s not an easy thing to explain, which is why so many Christians, both of the left and the right, think that “Christian values” means whatever their preferred political party’s preferred program is.

The core reason why Christian values are fast fading in this culture has to do with the loss of a sense of the sacred, of the transcendent, of what Philip Rieff called “holy terror” — his phrase for “fear of the Lord,” which is to say, a proper sense of awe in the presence of the divine. In his posthumous book “Charisma,” Rieff wrote:

“Holy terror is rather fear of oneself, fear of oneself and in the world. It is also fear of punishment. Without this necessary fear, charisma is not possible. To live without this high fear is to be terror oneself, a monster. And yet to be monstrous has become our ambition, for it is our ambition to live without fear. All holy terror is gone. The interdicts have no power. This is the real death of God and of our own humanity. It is out of sheer terror that charisma develops. We live in terror, but never in holy terror.”

He said this too, in the same book: “Barbarism is not some primitive technology and naive cosmologies, but a sophisticated cutting off of the inhibiting authority of the past.” This is perfectly true. This is why the dominant form of religion today is, to use sociologist Christian Smith’s phrase, “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism.” It’s crap. It’s what people believe when they want the psychological comfort of believing in God, but without having to sacrifice anything. It’s the final step before total apostasy. In another generation, America is going to be like Europe in this way.

But something might change. The problem with the phrase “Christian values” is that it reinforces the belief that Christianity is nothing more than a moral code. If that’s all Christianity is, then to hell with it. The great thing about ancient, weird, traditional Christianity is that it is a lifeline to the premodern world. It reminds us of what really exists behind this veil of modern selfishness and banality and evil. A Polish historian I interviewed this summer likened a civilization to a kite. As long as it remains anchored to the ground by a taut string, it can soar high. But when the string is cut, it falls to the ground. Our civilization is the kite that has cut the cord that anchors it to God, to the realm of the transcendent. That’s why we’re collectively falling. Traditional liturgical religion is the best chance we have to hold on to the cord or what remains of it. As Rieff put it, a true religious charismatic does not save us from holy terror, but conveys it. At their best, the old forms of Christianity do this — not through collective religious ecstasy, but through the prayers and prostrations and hymns that have been purified through many centuries of common use.

—

(You can read Tara’s piece in the NYT here.)

The post Weird Christianity: The Rod Dreher Interview appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 8, 2020

Weird Christianity In Covidtide

My pal Tara Isabella Burton, who is one of the most interesting religion writers today, has a piece in the NYT Magazine, which has posted it online in advance of weekend editions. It’s about “weird Christianity,” which she defines as follows:

More and more young Christians, disillusioned by the political binaries, economic uncertainties and spiritual emptiness that have come to define modern America, are finding solace in a decidedly anti-modern vision of faith. As the coronavirus and the subsequent lockdowns throw the failures of the current social order into stark relief, old forms of religiosity offer a glimpse of the transcendent beyond the present.

Many of us call ourselves “Weird Christians,” albeit partly in jest. What we have in common is that we see a return to old-school forms of worship as a way of escaping from the crisis of modernity and the liberal-capitalist faith in individualism.

Weird Christians reject as overly accommodationist those churches, primarily mainline Protestant denominations like Episcopalianism and Lutheranism, that have watered down the stranger and more supernatural elements of the faith (like miracles, say, or the literal resurrection of Jesus Christ). But they reject, too, the fusion of ethnonationalism, unfettered capitalism and Republican Party politics that has come to define the modern white evangelical movement.

Most of the people she interviewed for the piece are Millennials or younger, but she did talk to me too (I’m a Gen Xer). I had to laugh at the photo they used. The photographer took it in mid-February, when my hair was freshly cut, and my beard was short. I have neither cut my hair nor trimmed my beard since then, because of the lockdown. I’m starting to look like Grizzly Adams taking a graduate seminar in Hegelianism in Brno. Tara also interviewed my pal and Benedict Option practical genius Leah Libresco Sargeant, who said:

Leah Libresco Sargeant, a Catholic convert and writer who describes her views as roughly in line with that of the American Solidarity Party, which combines a focus on economic and social justice with opposition to abortion, capital punishment and euthanasia, rejects capitalist notions of human freedom.

“The idea of the individual as the basic unit of society, that people are best understood by thinking about them as sole lone beings” is fundamentally misguided, she told me. “It doesn’t make enough space to talk about human weakness and dependence” — conversations that she believes are an integral part of Christianity, with its concern for human life from conception until death.

That’s pretty much where I am politically, though I rarely write about economic policy. Here’s what I thought was the most interesting part of the TIB piece. “Garry” is John Garry, a college student and former alt-right guy who converted to Christianity via Weird Catholic Twitter, and now identifies as a Christian Marxist; “Crosby” is Ben Crosby, an Episcopalian seminarian:

It is unclear what the world will look like when the coronavirus pandemic, at last, comes to an end. But for these Weird Christians, this crisis doubles as a call to action. For Mr. Garry, the former Breitbart contributor, it has made plain “the absolute dearth of mutual aid in America.” Christianity, he told me, “compels us not just to take care of people around us but to seek to further integrate our lives and fortunes into those of the people around us, a sort of solidarity that necessarily entails creating these organizations to help each other.”

Mr. Crosby agrees. The pandemic, he said, has made all too clear that both liberal and conservative visions of American life, based on “self-fulfillment via liberation to pursue one’s desires” is not enough. “It turns out we need each other,” he said, “and need each other dearly.”

What Christianity offers, he added, is “a version of our common life more robust than individual pursuit of desire-fulfillment or profit.” In the light of that vision, the current pandemic can “be both a cross to bear and an opportunity to reflect the love that was first shown us in Christ.”

If Garry is calling himself a Marxist, then I cannot imagine that his politics and mine overlap much, but I think he’s quite correct in talking about “the absolute dearth of mutual aid in America.” I really identify with Crosby’s remarks about the failure of liberal and conservative visions of American life. As I’ve been saying here for weeks now, this virus really is an “apocalypse” in the sense of an unveiling. We get to see who we really are. A lot of it is ugly. The cost of social atomization — something that has been driven by many factors in American life since the end of World War II; you cannot blame it wholly on the left or the right — is making itself known. Our political leadership is poor, but so is our followership. I don’t see much of a sense of solidarity of any kind.

Can you really look to the churches for that — I mean, the churches as they are today? To be fair, nobody alive today has ever had to deal with anything like this, and it is extremely difficult for churches to do what they are used to doing when we have to live under such strict practices to avoid infecting each other. Still, I see this Covidtide to be a massive call to repentance for all of us. If we Christians had been living and praying and thinking like Christians — if our churches had discipled us, and if we had wanted to be discipled, instead of merely comforted — we wouldn’t be in such a mess today, facing this crisis.

I’m feeling this pretty acutely now because I’m winding up final edits and rewrites of my next book. That has meant spending more time with the stories and testimonies of believers who endured persecution under Soviet communism. Just today I was re-reading the transcript from my interview in Moscow last fall with Yuri Sipko, an older man who is an ordained Russian Baptist pastor, and who grew up in a heavily persecuted Russian Baptist community. Here are a couple of excerpts from the interview:

How did I find the strength to resist? I don’t know. We had a specific atmosphere in our family. I’m one of 12 kids. My older brothers and sisters had already gone through this. My father was the pastor of our congregation. All sorts of pressure was put on him. When I was a child, all I knew was that I wanted to be like my father. I could see that he had certain positions, and I saw that he was able to stand alone, against all of this pressure against him. He was able to stand up with dignity and courage. I wanted to be like him.

I was probably 10 years old when they first brought charges against him, and sentenced him for five years, for preaching. They sent him to prison in eastern Siberia for five years. I ended up not finishing school. I left in ninth grade, at 16 years old.

More:

Without being willing to suffer, even die for Christ, it’s just hypocrisy. It’s just a search for comfort. When I meet with brothers in faith, especially young people, I ask them: name three values as Christians that you are ready to die for. This is where you see the border. I don’t even value my life as much as my mission.

When I think about the past, and how our brothers were sent to prison, and never returned, I’m sure that this is the kind of certainty they had. They lost any kind of status, they were mocked and ridiculed in society. Sometimes they even lost their children. Just because they were Baptists, [the state was] willing to take away their kids and send them to orphanages. They were unable to find jobs. Their children were not able to enter universities. To get to universities you had to take an exam in scientific atheism. A believer could not pass this exam. But at least the battle was clear then. Today the truth has become blurry. The sharpness of this battle is not clearly defined.

What I would say to my Christian brothers in America is that you need to return Christ to the pedestal of your heart. You need to confess him and worship him in such a way that people can see that this world is a lie. This is difficult, but this is what makes man an image of God. As Christ said, “I am in the Father and the Father is in me. He who follows me will have eternal life.” If in our current life today, we’re leaving Christ over on the side, then we have a godless life.”

In Russia, as in the Soviet Union, it’s very weird to be a Baptist. But there is Yuri Sipko, completely fearless.

Tonight, as I finished work on a chapter featuring some of Sipko’s storytelling, I checked Twitter, and found this comment from Todd Starnes, a Southern Baptist #MAGA media personality:

A stern lecture. And no toaster for you! I mean, honestly.

If you think I’m holding myself up as better than Starnes, you’re wrong. I’m just as fat and coddled and as privileged as he is. If I have any advantage over him, it’s that the experience of sitting with brave souls like Yuri Sipko, and hearing their stories, was intensely convicting. Most of us American Christians have never been put to the test like the believers living under communist totalitarianism were. Many of us have never even been put to the test of sustained poverty. If you are like me, a middle-class Christian, don’t be sure at all how you would react if real persecution came. I’ll tell you this, though: if we can’t get through a pandemic that has killed almost 80,000 Americans in the past ten weeks, and put 34 million Americans out of work, without whining about our shopping experience being disturbed — well, what are we going to do if real persecution comes?

In Moscow, on the same day that I interviewed Sipko, I had dinner with Alexander Dvorkin, an academic who is an expert on cults. In talking about the potential for a new totalitarianism, he warned that a society in which there is a great deficit of solidarity is one that is prone to capture by a cultish mass leader. “There is a danger that the desire to belong will prevail over truth,” he told me. “All revolutions are carried out by people who have found [in their ideology] a strong sense of belonging.”

One way or another, Americans are going to rediscover a sense of belonging. The pandemic and the economic depression is revealing the radical insufficiency of our way of life — and, I would emphasize for my fellow Christians, the radical insufficiency of our way of Christian living. We need “weird Christianity,” in the sense of a deep and rooted Christianity that is countercultural. To be a countercultural church in America today is to be a church that practices solidarity, and is preparing its people to suffer the loss of status, the loss of material possessions, and maybe even the loss of freedom. To be a countercultural Christian in America today means being radical.

I am an Orthodox Christian. I wish you would become one too. But joining an Orthodox parish — or a Catholic one, or an Anglican one, and so on — is not going to be enough. Yuri Sipko is a Baptist, which is about as far away from Russian Orthodoxy as you can get. But that man has within him what it takes to endure. It was placed there by his family, and the community in which he was raised. It came from his churching.

I can’t say enough about what God has done for me through the prayers, the liturgies, and the spirituality of Orthodox Christianity. It is pretty weird in America, and thank God for that. One of the most important things is finally getting it through my thick head that all of that “weird Christian” stuff is about breaking down the barriers between the self and God. That the Christian life is about constant repentance. I don’t mean that it’s always sorrowful; joy and feasting is also central to the authentic Christian life. But the Christian life is a constant pilgrimage of inner conversion, of dying to self, and of awakening to yourself as a new creation. I’m sorry to be all preachy here, but this past year of reading stories about Christian life under communist totalitarianism, and talking to older men and women who lived through it, has been for me, as a comfortable middle-class American Christian, a call to repentance.

I’m not sure what that is going to look like when this coronavirus plague passes. I’m not sure what that’s going to look like in two or three months, when it hasn’t passed, but we have to find some way to live so we can feed ourselves. I do believe, though, that God is calling all of us Christians to walk away from our soft, gripey, self-centered way of living, individually and as a community. He always has been doing that, but now, this crisis could be a special mercy, given to wake us up to the true condition of our souls.

Politics of the left or the right is not going to save us. It might help somewhat, but what needs healing in this country is deeper than politics. Shallow, emotional religion won’t save us either — but don’t be deceived into thinking that getting a prayer rope, or praying in Latin on Sunday morning, will do the trick, unless it all leads to conversion of the heart. A lesson that I still struggle with, almost 14 years after becoming Orthodox: the prayer rope is meaningless if it stays wrapped around your wrist; it only works if you pass it through your fingers (which is to say, it’s only useful if it helps you actually to pray).

OK, sermon is over. I’ve been hearing from some of you Christian readers who have been sending me stuff you’ve taken off social media from your Christian friends. It’s depressing — the paranoia, the conspiracy theories, the people giving themselves over to political fantasies that stoke their freakout, rather than help them to build spiritual and moral resilience for the long, difficult road ahead. One reader said to me that she was planning to quit Facebook, because she can’t stand to see people — fellow Christian people — she knows and loves saying crazy things, and ugly things, out of a spirit of fear and rage. I’m not on Facebook myself, but it might not be a bad idea to do the weird, un-American thing, and quit Facebook for the good of your soul.

What do you readers think? What could “weird Christianity” do for the broader church? What qualifies as “good weird,” and what qualifies as “bad weird”?

The post Weird Christianity In Covidtide appeared first on The American Conservative.

Covid-19 And The Common Good

I was just on a long Zoom session with some TAC folks, in which Claes Ryn discussed the personality required to live successfully under the US Constitution. There was talk about the “common good,” and it made me wonder what that even means anymore. I’m still sore about the whole mask issue. It’s not that I am opposed to people objecting to the mandate to wear masks. It’s that I’m not hearing these people talk about the issue in terms of the ineffectiveness of masks (some people are! but not the angry people); I’m hearing them frame the issue wholly in terms of personal liberty. I’m so used to hearing this kind of thing from the left — that any restriction or limit on what they want to do is intolerable oppression. I am super-sensitive to hearing it from the right.

Then I received this e-mail from a Pennsylvania reader named Kevin, who has given me permission to post it:

I wanted to reach out to raise something with you to see if you have been seeing this as well. Among my friends who attend more charismatic and Pentecostal denominations, there is this widespread sense that the death numbers are fake, the polling that shows lockdowns are generally favored is fake, and that polling showing Trump’s approval on the crisis is in the toilet is fake. These are also the folks who generally ascribe to the Trump as Cyrus (or King David) view. I understand we are to live by faith, not by sight – but we are also called to seek wisdom, knowledge and understanding.

And, Rod, what tears my heart up so much is what we are seeing from the data is this virus disproportionately harms the elderly, the poor and black people. It just isn’t fair. Haven’t we been called by Scripture to lay our lives down – particularly for the marginalized, the widow and the orphan, the foreigner and the oppressed? I have my objections to the social justice movement just as you do, but here just as when we have been asked to engage in a country-wide project of compassion, I weep that I see so many in the church – in my church – that want to dismiss it. Perhaps for the reasons you have laid out, based on the Heterodox Academy’s research.

I wanted to highlight a recent Twitter thread from Southeastern University theology professor Chris Green, that begins with this thunderclap of truth: Conspiracy theories are needed when you’re socialized to question every authority but your own. https://twitter.com/cewgreen/status/1258489625842274306

I recognize we have to make some tradeoffs. I am not advocating for perpetual lockdowns. I work for a chamber of commerce, and every we get calls from companies who want to re-open, because they are on the brink of collapse. And do you know what Rod? The employees don’t want to come back. They are scared for their lives. And I don’t blame them.

What also frustrates me is we did these lockdowns not just as an act of compassion, but so that we could increase medical supplies, testing and treatments – and to come up with an actual plan. Ari Schulman at the New Atlantis made this point well the other day. https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/whats-the-plan. And now we read that ventilators aren’t effective, we can’t seem to get testing off the ground, and any promising treatment – hydrochloroquine and remdesivir come to mind – are either harmful or only mildly effective. Where is our plan? Does anyone actually have a plan? Or have we wasted two months?

Yesterday I read Isaiah 2 and 3 as part of my morning devotions. While I think we need to be very careful about taking OT verses and applying them directly to contemporary events (see above, re Trump and David/Cyrus comparisons) it should tell us something that God, through Isaiah, tells Israel there will come a day when He will frustrate the wise, strip the nation of its wealth and its command over nature and technology, and leave the people in hiding. When I look at the nation by nation data, it is apparent to me that, even adjusting for population and China’s downplaying of the magnitude there, we are being uniquely humbled and humiliated.

And rather than look this squarely in the eye – that this is harming the poor and the elderly, that our leadership is failing us, that we are too prideful to accept authority from politicians of another party (why is Trump God’s anointed but not a Democratic governor?), that we are being asked to lay down our idols of comfort and power and security – we must retreat to an ideological lens. Because Trump might appoint some more pro-life judges in 2022? Hannah Arendt was right.

I presume Kevin is talking about Arendt’s claim that one sign that a country is in a pre-totalitarian state is when people within the country prefer ideological claims to the truth. That is, when they would rather hear things that confirm what they already believe than to deal with truth that makes them angry or anxious. People like that — and we have them on both the left and the right — are sitting ducks for a leader who knows how to manipulate them.

You have probably heard the news about the unemployment rate:

The nation’s economic distress came into greater focus on Friday, offering a snapshot unseen since the Great Depression.

The Labor Department said the economy shed more than 20.5 million jobs in April, sending the unemployment rate to 14.7 percent as the coronavirus pandemic took a devastating toll.

The monthly data underscores the speed and depth of the labor market’s collapse. In February, the unemployment rate was 3.5 percent, a half-century low.

And the damage has only grown since then: Millions more people have filed claims for unemployment benefits since the monthly data was collected in mid-April.

“It’s literally off the charts,” said Michelle Meyer, head of U.S. economics at Bank of America. “What would typically take months or quarters to play out in a recession happened in a matter of weeks this time.”

Scientists say that barring a vaccine, we are going to have to get used to living with waves of Covid-19 for possible two years:

What is clear overall is that a one-time social distancing effort will not be sufficient to control the epidemic in the long term, and that it will take a long time to reach herd immunity.

“This is because when we are successful in doing social distancing — so that we don’t overwhelm the health care system — fewer people get the infection, which is exactly the goal,” said Ms. Tedijanto. “But if infection leads to immunity, successful social distancing also means that more people remain susceptible to the disease. As a result, once we lift the social distancing measures, the virus will quite possibly spread again as easily as it did before the lockdowns.”

We are going to have to get ourselves in order, or we are not going to make it through this next year or two. We cannot carry on like this. We need credible leadership. I’m not sure what that looks like, because we’ve not seen a lot of it. We also need credible followership. I’m not exactly sure what that looks like either, other than at the very least refusing to accept conspiracy theories and theories that “feel right.”

There’s a lot we don’t know about this virus. We can’t expect scientists and government officials to get this 100 percent right every time. The information we have had from the experts regarding mask-wearing has been contradictory. A reader points out that Michael Osterholm, one of our top experts, says that there’s no evidence that cloth masks at all impede the spread of coronavirus.

But the CDC still recommends their use. The Mayo Clinic says that they may provide some protection, and recommends their use. I think we just don’t know for sure. I don’t think people should get so angry and political about masks! It is a legitimate debate over whether or not we should wear them. Personally, I think it’s a minor inconvenience, and if my governor says he wants me to wear them when I go out in public, I don’t mind doing it until it is definitively shown that it’s pointless. Remember, these cloth masks are not to keep you from getting sick (they don’t really work that way), but to make it less likely that you will pass on the virus to others if you are infected but asymptomatic. As I see it, this is a tiny sacrifice to make for the health of others — in particular store clerks, who are serving people like me, even though they risk exposure to the virus.

As I write this, I’m hearing that Donald Trump’s valet — the man who served him dinner — has tested positive for Covid-19 — and did not wear a mask. I bet the president wishes now that the valet had.

We are not the resilient country that we once would have been. What is being revealed by this thing is a country that has ceased to believe in the common good, and in which many individuals think that they should not have to give up anything at all for the sake of others.

The post Covid-19 And The Common Good appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 7, 2020

Anti-Mask Snowflakes Of The Right

Look, I understand people are mad about social distancing and wearing masks, but a lot of people on the Right are losing their minds. Here’s something from a column by Dan Fagan in my local paper, the Baton Rouge Advocate:

The far-reaching, extreme, and radical measures governors like [Louisiana Gov. John Bel] Edwards imposed during the COVID-19 scare represent the greatest challenge to individual liberties since the inception of our great nation. Some of us are reaching a boiling point.

I’d say you’ve boiled your brain, Cap. This nation was founded in 1776. Here are a couple of challenges to individual liberties since then — challenges that took place right here in our state — that were arguably more important than having to wear a mask when you go out for a po-boy during a pandemic:

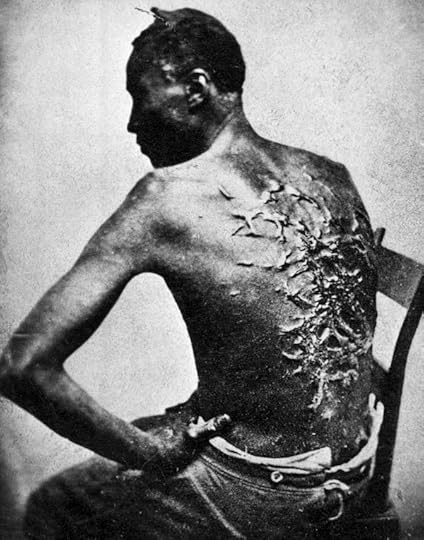

The back of a Louisiana cotton plantation slave who had been whipped by his owner, Captain John Lyon (Bettmann/GettyImages)

The back of a Louisiana cotton plantation slave who had been whipped by his owner, Captain John Lyon (Bettmann/GettyImages) Women at William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans yell at police officers during a protest against desegregation at the school, as three black youngsters attended classes at the school. Some carry signs stating “All I Want For Christmas is a Clean White School” and “Save Segregation Vote, States Rights Pledged Electors” (Bettmann/GettyImages)

Women at William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans yell at police officers during a protest against desegregation at the school, as three black youngsters attended classes at the school. Some carry signs stating “All I Want For Christmas is a Clean White School” and “Save Segregation Vote, States Rights Pledged Electors” (Bettmann/GettyImages) State militia guard a jail and courthouse to prevent a lynching. Shreveport, Louisiana, 1906. (Photo by Michael Maslan/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

State militia guard a jail and courthouse to prevent a lynching. Shreveport, Louisiana, 1906. (Photo by Michael Maslan/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

So yeah, we have had a few things that were a little bit more of a challenge to civil liberties than the mask. Still, Dan Fagan demands to know:

How much further are they going to go? When will this all end? When do we go back to being free?

Oh for Pete’s sake. Late last year, I sat in a shabby apartment in Moscow, interviewing an elderly man whose father was tortured and executed by the KGB, and who, as a 15-year-old boy, was taken into custody by the KGB one night, and thrown into a prison for years. He cried telling me the story. And now I have to read my local newspaper conservative whine about how we’re living in a police state because of the stupid mask he has to wear when he goes out to buy a six-pack. If the KGB came knocking at the door of Dan “Boiling Point” Fagan, he would spontaneously combust. Hell, if a meter maid came for Dan Fagan’s car, he would soil his britches and squall like the Constitutional Peasant:

Seriously, what is wrong with conservatives? Can we not raise objections to masks, social distancing, and the pandemic protocols without making fools of ourselves? The stories I’m hearing from conservative friends around the country are really embarrassing. Mask off, if that’s what you want, but please, grow up.

The post Anti-Mask Snowflakes Of The Right appeared first on The American Conservative.

Your Story About Yourself

This has been going around Twitter. It’s from a podcast interview Tim Ferriss did with the great nonfiction writer Michael Lewis:

That’s really something, isn’t it? I’ve often heard it said that we live not so much by principles, but by stories. In my book How Dante Can Save Your Life, I wrote:

Neuroscientists have found that the telling of a story, no matter how simple, lights up parts of our brains that lie dormant when we merely process language. In fact, research has shown that the brain reacts to stories in the same way it responds to actual events. When a story fully enters into your imagination, it is as if you experience it yourself. The more vivid and sensual the descriptions within a story, the more powerfully its lessons, moral and otherwise, lodge in the brain.

Annie Murphy Paul, writing about these discoveries in the New York Times, observed: “Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.”

Here’s a link to that 2012 piece by Annie Murphy Paul. In it, Paul continues:

Raymond Mar, a psychologist at York University in Canada, performed an analysis of 86 fMRI studies, published last year in the Annual Review of Psychology, and concluded that there was substantial overlap in the brain networks used to understand stories and the networks used to navigate interactions with other individuals — in particular, interactions in which we’re trying to figure out the thoughts and feelings of others. Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers.

I wonder how these findings apply to the self-narratives we employ, in the sense Michael Lewis means.

I’m thinking of a friend whose stories about herself always, always have her being victimized by someone, or by life. I used to think wow, people sure are mean to her or she sure has drawn a bad hand. But as I got to know her better, and as I began to see her interact with mutual friends, I came to see that her perception was very far from how things actually were, at least in the interactions with which I had personal knowledge. Long story short: I learned eventually that my friend had had a traumatic, emotionally abusive childhood, and had come to expect that people would mistreat her. She always seems to be looking for the hidden angle, for the way others are trying to put her down. If you say to her something like, “Martha [not her real name], you did well. They really liked you!”, she will respond that if I only saw how things really were, I would know that deep down, those people hate her. And if I push back, and insist that no, they really do like her, and that she is imagining that they don’t, she will accuse me of demeaning her judgment, and putting her down like all those other people do.

I talk about this in the present tense, but truth to tell, I have intentionally grown distant from “Martha” over the past few years. It’s too exhausting to be her friend. You get tired of all the neurosis. I’m sure she thinks, “See, I was right about Rod. He hates me too! They all do!” In fact, Martha’s is a sad case of self-sabotage. She has a good heart, and certain gifts, but the story she has spent a lifetime telling about herself — that she is one of life’s victims — is one that she eventually lived into.

Thinking about poor Martha, I find it puzzling that she could never accept good news about herself. I did not know her when she was younger. I don’t know if there was ever a time when she might have been able to change her story, to refuse the story that she had received from her abusive childhood. Talking to a guy who had been part of Martha’s circle at one time, he told me that he quit hanging out with her because he got tired of hearing her gripe all the time about all the people who were doing her wrong. Indeed, as I’m sitting her typing, I’m thinking of happy stories Martha has told about herself, and how often they end with some form of, “… but that didn’t last, because [somebody else betrayed or hurt me].” In fact, I know that she has probably driven more than just that one person away from her, because she lived in such a way as to make her negative self-narrative come true. I know all too well from personal experience that suggesting to Martha that she has it wrong, that she is not a victim, that life is not a dark as she thinks it is — that gets absolutely nowhere. It’s as if she is so dependent on the narrative of herself as Victim that she fears surrendering it would unleash chaos. At least the world makes sense in that narrative — and her sense of needing to control the world matters more than wanting to be happy and at peace in it.

And you know, I am certain that Martha doesn’t realize that her narrative is a construal. She cannot comprehend that she might be seeing things incorrectly. She thinks that she’s living in truth, but in fact she’s living within a story she was written for herself. A little postmodernism would do Martha a lot of good.

Question to the room: is there a pattern in the way you talk about yourself? Ever thought about it? I haven’t ever thought about it with regard to myself. If I had to guess, my self-narrative usually involves me wandering into a situation in which I have some epiphany — I met the most amazing person/saw the most amazing thing/tasted the most amazing dish — that compelled me to rethink my approach to life in some way, or at least reaffirmed gratitude for the thing I was shown. My stories about myself generally construe myself as a Pilgrim of some sort: someone who sees life as a journey, along which I meet enchanted people, mysterious castles, wicked dragons, and so forth, and find some way to discern meaning from those encounters, and integrate those them into my own perspective. Sometimes in the telling of these stories I am a Pilgrim who is also a “fortunate fool.” There is often a quality of gentle self-abasement to my stories, which sometimes signals that I see myself as unworthy of this knowledge or these experiences. I think the sense of naive wonder I bring to these tales must irritate people — I would probably be irritated if I saw that in others — but for better or for worse, that’s who I am.

But at other times — when I am not so gentle in my self-abasement — means that I was lucky enough to discover what a fool I had been, so that I would not be that same fool in the future if I could help it. There is a quality of confession and atonement in those self-narratives, and I am quite conscious of it. When I tell the story of how I supported the Iraq War, I try to be hard on myself, because I don’t want to be that man again, and I want my listeners to understand how we can lie to ourselves even when we think we are being brave and truthful. When people ask me how I lost my ability to believe as a Catholic, I tend to focus more on my own idolatry of the Catholic Church than on the bad things the Church did. I do that because I want to own my sins, and my part in that painful episode — and do not want to repeat it, and do not want my listeners to set themselves up as idol-worshipers. Auden said (you’ll see the full quote below) that when we are falsely enchanted, we end up wanting to possess the object of enchantment, or wanting to be possessed by it. That’s how I was with Catholicism: I wanted it to possess me. That’s my fault, not Catholicism’s — and that’s the story I want to tell all Christians. Because it could happen to them too. Anything that is not God, but that we wish to possess or have possess us, can become an idol. This is a hard, hard lesson my pilgrimage has taught me.

There’s no doubt that Orthodox Christianity has played a big role in helping me not only to sharpen my sense of myself as a pilgrim, but also as a fortunate fool. Longtime readers will know that within about a single decade — from 2001 till around 2013 — I lost the three frames that helped me understand the world and my place in it. I lost my Catholic faith, I lost my faith in conservative politics, and finally, I lost the illusions I had about my family back in Louisiana (which I had also idolized, in the same way I idolized Catholicism). You can see why Dante’s Commedia was such a godsend! What it taught me to see — and this was backed up by Orthodoxy — was that everything we experience can be an opportunity for deeper conversion, for a more profound dying to self, and awakening to God.

I have always been a seeker and a pilgrim, but the tragedy of that decade of my life made the story darker, but maybe also filled it with more light. I’m not sure, because I don’t stand outside of myself. Just this morning I found this quote from W.H. Auden, and it deeply resonated with the pilgrim inside me:

The state of enchantment is one of certainty. When enchanted, we neither believe nor doubt nor deny: we know, even if, as in the case of a false enchantment, our knowledge is self-deception.

All folk tales recognize that there are false enchantments as well as true ones. When we are truly enchanted we desire nothing for ourselves, only that the enchanting object or person shall continue to exist. When we are falsely enchanted, we desire either to possess the enchanting being or be possessed by it.

We are not free to choose by what we shall be enchanted, truly or falsely. In the case of a false enchantment, all we can do is take immediate flight before the spell really takes hold.

Recognizing idols for what they are does not break their enchantment.

All true enchantments fade in time. Sooner or later we must walk alone in faith. When this happens, we are tempted, either to deny our vision, to say that it must have been an illusion and, in consequence, grow hardhearted and cynical, or to make futile attempts to recover our vision by force, i.e., by alcohol or drugs.

A false enchantment can all too easily last a lifetime.

So, to recap: I don’t know for sure what the stories I tell about myself are really like. I could be completely deceiving myself! I haven’t thought about it ever, until reading that Michael Lewis quote. If I am any sort of wayfaring pilgrim in the pattern of my self-narrative, I think it must surely be in part because I subconsciously came to see myself that way, and have opened myself to experience over the years (that is, the kind of experiences that someone who was trying to be a pilgrim — a wayfarer on a mission — would have). There are few experiences more precious to me than learning that I have been wrong about something, or somebody, and the truth is more beautiful than I could have imagined. Following Lewis’s insight, I think it must surely be true that the reason I keep having these pilgrim’s-path epiphanies is because I have become that kind of character in my self-narrative, without quite realizing what was happening.

Let me ask you the same question. Try to be as honest as you can be. If people only knew about you from the stories that you tell about yourself, what kind of person would they think you are? Is that who you really are? Why or why not?

The post Your Story About Yourself appeared first on The American Conservative.

Robespierre And Auden, Autists

Some years ago, in Paris, my son and I read Christopher Hibbert’s history of the French Revolution. When we were done, we talked about how the book had inadvertently convinced us that Maximilien Robespierre was on the autism spectrum. (This, because both of us slightly are, and we recognized the signs.) I wrote this back in 2012 on this blog, but I’m re-upping it because the blog has many more readers today. (I also later read Ruth Scurr’s great book on Robespierre, Fatal Purity.)

We made our case that Robespierre was a high-functioning autist from what we know of Robespierre’s manner. All quotes below are taken from Hibbert’s book. For example:

1. Robespierre was extremely nervous and high strung.

2. He was very fastidious about his appearance.

3. “He rarely laughed, and when he did, the sound seemed forced from him, hollow and dry.” Some people who are more intensely on the spectrum do sound forced in their laughter, because they have trouble gauging emotion and its proper expression.

4. “He appeared to be unremittingly conscious of his own virtues.” This is key, because many spectrum folks are rather severe in their sense of order, and intolerant of anyone who doesn’t think and behave in what they consider to be the “correct” way.

5. “But if [young Robespierre] joined in [his sisters’] games, it was usually to tell them how they ought to be played.” Standard behavior. My late father, who was the coach of my Little League team, told me that he always felt so sorry for me as a player, because the game was nothing but a source of stress for me. He said that he could always tell that I had worked out in my mind, before every pitch, where the correct play would be, no matter where the ball would be hit. But I could not enjoy myself, because none of the other boys, being little kids who just wanted to have fun, would focus on the mechanics of the game, to my satisfaction.

6. “… and when they asked [young Robespierre] for one of his pet pigeons he refused to give it to them for fear that they might not look after it properly.” Again, standard behavior.

7. At university, “He seems to have been a solitary student who made no intimate friends and was apparently content to spend most of his time alone in the private room with which his scholarship provided him.” Spectrum folks tend to be loners.

8. According to his sister, the adult Robespierre “was almost completely uninterested in food, living mainly off of bread, fruit, and coffee.” Autists tend to eat simple diets, in part because of the predictability of a simple diet, and in part because sensory variety is unpleasant to them.

9. He would lose himself in his work, sometimes forgetting that there were other people around him, or what had been going on around him. Autists are characterized by their intense focus on their work, or whatever occupies their attention at a given moment. This, by the way, is one thing that my son and I share. Just the other day, my daughter stood next to me saying, “Dad. Dad!” five times before I heard her. I was laser-focused on a book I was reading. It’s kind of a super-power, but it also gets you into a world of trouble under certain conditions.

10. He was not a carnal man, nor was he interested in ordinary pleasures. Even when he was the most powerful man in France, he kept his same spare rented rooms in the rue Saint-Honore, and didn’t use his position to make his life more lively or comfortable. The work, and living by virtue, was the thing.

The called Robespierre “L’Incorruptible,” and I believe it. But I don’t think it was a matter of virtue, as people believed at the time, as much as it was neurological. He believed in a severe code of behavior, and followed it because that’s what made him feel at home in the world. He was incorruptible for the same reason that someone who has sensory processing disorder (a syndrome associated with autism) can’t wear a shirt with a tag in the back: it is extremely irritating.

The problem is that when Robespierre came into a position of supreme power, he tried to force all of France to do what he believed needed to be done. He saw the people as a problem to be solved. He saw governing as a game to be played strictly according to his rules. That did not work out well for all the people he sent to the guillotine. Eventually, he was made to join their number. He no doubt went to his death genuinely not understanding what he had done wrong.

Do I really need to say that I don’t believe people on the spectrum are all bloody-minded dictators in waiting? Yes, I probably do. In fact, people on the spectrum really do have gifts. I used to work for the philanthropy founded by the late Sir John Templeton, a legendary stock-picker. He died before I joined the foundation, but the more I talked to people who had known him, the more I picked up clues that the cheerful investor might have been on the spectrum. Once I visited his old office in the Bahamas. Someone who had been there with him told me that it was amazing to watch him work. They told me he would spread the stock pages out in front of him at his desk, and go into a kind of fugue state, deeply concentrating on the data. And then he would come out of it, and make his stock buys. This is how he became a billionaire.

I heard that and thought, “Of course! If he was on the spectrum, then he was able to perceive patterns in the stock data that nobody else could.” This, you might know, is how Michael Burry, the investor profiled in Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, became a billionaire. He saw stock market patterns leading up to the 2008 crash that nobody else could see.

There’s a blogsite called Autism-Advantage.com that talks about how autism really does help one think through certain problems. For example:

In an interview on MBUR, Michael Lewis commented about Michael Burry and Asperger’s Syndrome:

“ … it’s not an accident that these people are the ones who saw what the system failed to see and was blind to. They had qualities in them that enabled them to see. And in his case, it was a total resistance to the propaganda coming out of Wall Street coupled with an insistence on seeing what the numbers were.”

In reality, people on the spectrum are not seeing anything differently to what everyone else sees. Autists are not better at looking per se. But what they are better at is removing the obstacles that obstruct the view. The “unique insights” or “creative solutions” that are often cited in regards to autistic employees are often not much more than being able to see what’s staring us in the face, of being able to “cut through the crap” (excuse the French). When solutions are hard to find, even when they shouldn’t be, it can often be because we’re misled by “this is how we did it last time”, “we always do it like this” or “everyone feels that this is the best approach”. None of which cut any ice for an autist and none of which will necessarily help find a solution.

A Vancouver-based consultancy, Focus Professional Services, speak of their autistic consultants as having “unique ways of filtering information”. This goes to the heart of the autistic advantage: being able to eliminate unnecessary and confusing data by rejecting information noise.

If you’re searching for a needle in a haystack, the first thing you want to do is reduce the size of the haystack. And autists are very good at removing hay.

A reader wrote to me this week that I remind her of a roommate she once had, a woman who was on the spectrum. My correspondent said that her friend had a PhD in the hard sciences, and always had

this annoying habit of always darkly prognosticating about trends in society and science. I used to inwardly pooh-pooh her ideas about many things, or argue with her that her views were too dark. But, dang! She was nearly always right! The thing I realized is that she did not let her emotions cloud her judgment with a desire for things to be a certain way. I think this allowed her the ability to clearly see patterns in society that led her to crucial and unpopular but logical conclusions. It was as if she could just turn off her emotions with a switch — what a gift!

And yes, the friend had been diagnosed as on the spectrum. Anyway, the correspondent said she has wondered if this expresses itself in me with regard to seeing the logic of underlying patterns and forces in society and culture. I have thought that too — the extent to which my cultural pessimism is based on the perception of deep patterns in cultural life that elude most people’s vision.

Just yesterday, I mentioned to my wife that a friend of ours reacted badly when I sent the friend a news article about how an event in the friend’s city might be shut down in 2021. “How strange that she would react that way,” I said to my wife. My wife said that it’s not strange at all. “One thing that makes you good at your job,” my wife said, “is how you can separate your emotions from things you read. But most of us can’t do that. Most of us don’t find it easy to read bad news.”

Well, she has a point. My wife has always wondered how on earth I can lie in bed at night, read a history of the gulags, or the Holocaust, then turn the light off and go right to sleep. Come to think of it, that’s why so many people who only know me from my writing perceive me as much gloomier than I actually am in real life. I really can turn this stuff off. For me, doing this blog is like the old Warner Bros. cartoon about the sheepdog and the coyote, both clocking in to play their roles:

I’m not “playing a role” to be fake; I’m just saying that I can switch easily from the intensity of writing about the news, and decline-and-fall, to ordinary life. Cheerful life, believe it or not. It’s just business. Serious business, but just business. I am often surprised when others can’t do that. That’s a fault of empathy on my part — though when I do find empathy for someone, boy, does it ever take off like a rocket.

The weird thing is that I can focus like a laser on certain things, but others fall by the wayside, sometimes in big and consequential ways. I was once editor of a newspaper section. I can say with no false modesty that I was superb in finding essays to publish, and composing a balanced, interesting section, week after week. But I was terrible at doing the non-idea-related detail work necessary to be an editor — things like making sure writers got paid on time. Eventually I had to step down. Thinking back on it, whatever very mild autism I have made me exceptionally good at finding unusually interesting essays and editing them for publication. But it also made me a disaster at the important managerial work that needed doing for the section to function. I genuinely could not focus on that stuff; I was thinking constantly about the Big Ideas.

I was like this in college. My grades were not great. Maybe I graduated with a 3.2 GPA. Straight As in history, English, humanities; abysmal grades in math and science. I don’t actually believe I was as bad as all that in math and science. I believe that I could not bring myself to hold the focus I needed to do to succeed. I don’t know where the line was between laziness (a moral fault) and neurological incapacity. I used to think it was 100 laziness, but having learned more about the autism phenomenon through my family’s experience with it, I think the explanation is more complicated.

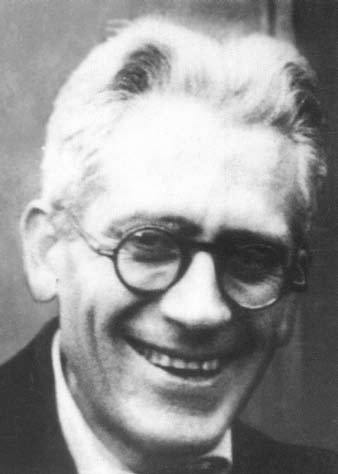

My desk, and my bedroom, have always been a huge mess. At some point my wife gave up on me. If you go into our bedroom now, it looks like Goofus and Gallant share a bed. Her side of the room is neat and clean. My side, full of books and papers stacked everywhere. I read the other day in a Clive James essay that W.H. Auden, who wrote the most crystalline, well-constructed poetry, was a world-class slob. I mean, off the charts messy. Just now, as I was writing this blog entry, I thought, “I bet he was on the spectrum.” Lo, I did a bit of online research, and indeed Auden diagnosed himself as on the spectrum. Not surprised. Not surprised at all.

Well, sorry for that digression. Because of my own, and my own family’s, experience with neuro-atypicality, I am fascinated by the way this phenomenon manifests itself in different lives and contexts. Robespierre is obviously a great outlier. Still, it’s fascinating to think about how the arc of his extremely consequential life might have been shaped by autism. Robespierre started out as a provincial lawyer who fought for justice for the poor. He was, no kidding, a social justice warrior — and I mean that in a complimentary sense. Can you imagine the courage it must have taken to fight for the poor under the French monarchy at the time? Well, Robespierre did. He hated injustice. Couldn’t live with it.

And then, years later, when he had become the most powerful man in France, his white-hot passion for justice, untempered by mercy and the capacity for empathy, became extreme cruelty.

It is easy to discriminate against autists, even those with high-functioning autism. They can be difficult to deal with. But they often have real gifts — somewhat unique gifts — that can serve the community if they are allowed to flourish. What they need (and I’m talking here about myself, though again, I’m probably not diagnosable) is the freedom to do what they’re good at, but also the limitations to keep them from attempting what they’re not suited for. You need Mr. Spock on the bridge of the Enterprise, but you don’t really want Spock to be the captain.

UPDATE: Auden once wrote:

Between the ages of six and twelve I spent a great many of my waking hours in the fabrication of a private secondary sacred world, the basic elements of which were (a) a limestone landscape mainly derived from the Pennine Moors in the North of England, and (b) an industry — lead mining.

It is no doubt psychologically significant that my sacred world was autistic, that is to say, I had no wish to share it with others nor could I have done so. However, though constructed for and inhabited by myself alone, I needed the help of others, my parents in particular, in collecting its materials; others had to procure for me the necessary textbooks on geology, machinery, maps, catalogues, guidebooks, and photographs, and, when occasion offered, to take me down real mines, tasks which they performed with unfailing patience and generosity.

From this activity, I learned certain principles which I was later to find applied to all artistic fabrication. Firstly, whatever other elements it may include, the initial impulse to create a secondary world is a feeling of awe aroused by encounters, in the primary world, with sacred beings or events. Though every work of art is a secondary world, such a world cannot be constructed ex nihilo, but is a selection and recombination of encounters of the primary world…

Secondly, in constructing my private world, I discovered that, though this was a game, that is to say, something I was free to do or not as I chose, not a necessity like eating or sleeping, no game can be played without rules. A secondary world must be as much a world of law as the primary. One may be free to decide what these laws shall be, but laws there must be.

The post Robespierre And Auden, Autists appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 6, 2020

Google App Censoring Covid-19 Courses

I have taken and really benefited from the Great Courses series of recorded college lectures. The one on Dante is so great that I wish I could buy a copy for everybody I know. Turns out that the Great Courses folks recorded some lectures from academic authorities offering takes on Covid-19.

A reader writes tonight:

A friend of mine took these screenshots. I have no idea the quality of the lectures on Great Courses, or if the info is legitimately misinformation, but it seems a bit dangerous for google to be able to censor apps that have info about COVID-19.

Here are the screenshots:

Here is a link to the Great Courses YouTube page.

Here is a link to TheGreatCoursesDaily.com.

Here is a link to Dr. David Kung’s app-banned clip on How Math Predicts the Coronavirus Curve.

Here is a link to Dr. Kevin Ahern’s app-banned clip titled Viral Intelligence: What Is Coronavirus?

Here is a link to Dr. Roy Benaroch’s app-banned clip titled Coronavirus Outbreak: What You Need To Know

What could these courses possibly say that offends Google? Maybe Google simply has a blanket policy of not allowing any non-official Covid-19 discussion on its platform. If that is the case, then the reader is right: it is really bad news that Google exercises its right to censor any non-government app featuring Covid-19 information — even from college professors.

Google is a private entity. It has the right to control what goes out on its app platform. Whether Google is morally correct to exercise that right to suppress any unofficial pandemic information is a different question — and a very important one. Google owns YouTube — how long will they allow these courses to remain on YouTube?

The post Google App Censoring Covid-19 Courses appeared first on The American Conservative.

Child’s Public School Apocalypse

“Apocalypse” means “unveiling.” In this space before, I have written about what a revelation it was to me to go off in 11th grade to a public school for gifted kids, and to experience for the first time a class where the teacher didn’t have to spend half her time trying to get the kids to shut up and pay attention. I had come from one of the best normie schools in the state, and still, the teachers had to be disciplinarians as much as pedagogues. This was the normal state of things. I was genuinely shocked by how much material we could cover in class when the poor teacher wasn’t compelled to ride herd on kids who didn’t want to be there, and who didn’t give a flip about learning.

Well, today’s New York Times publishes something that would never, ever get into the paper if it had been written by an adult. It was written by Veronique Mintz, an eighth grader in a New York City public school. She says — are you ready for this?:

Talking out of turn. Destroying classroom materials. Disrespecting teachers. Blurting out answers during tests. Students pushing, kicking, hitting one another and even rolling on the ground. This is what happens in my school every single day.

You may think I’m joking, but I swear I’m not.

Based on my peers’ behavior, you might guess that I’m in second or fourth grade. But I’m actually about to enter high school in New York City, and, during my three years of middle school, these sorts of disruptions occurred repeatedly in any given 42-minute class period.

That’s why I’m in favor of the distance learning the New York City school system instituted when the coronavirus pandemic hit. If our schools use this experience to understand how to better support teachers in the classroom, then students will have a shot at learning more effectively when we return.

More:

I have been doing distance learning since March 23 and find that I am learning more, and with greater ease, than when I attended regular classes. I can work at my own pace without being interrupted by disruptive students and teachers who seem unable to manage them.

Students unable or unwilling to control themselves steal valuable class time, often preventing their classmates from being prepared for tests and assessments. I have taken tests that included entire topics we never mastered, either because we were not able to get through the lesson or we couldn’t sufficiently focus.

Mintz offers “lessons learned,” but they are the wrong lessons — lessons that would add more work to already heavily burdened teachers, while requiring nothing of these brats who refuse to behave. Anyway, they won’t work. The “lessons” reflect the mindset that says the problem is with the teachers and the pedagogical system, when the fact is, it’s with these kids who have no respect for their teacher and fellow students, and no self-discipline.

The real lesson from Mintz’s experience is that her parents need to get her out of that school and into either a well-disciplined private school, or some kind of homeschooling, perhaps online. Many years ago, after my wife began homeschooling our kids, my sister, who was a (very good) public school teacher, expressed skepticism that they could learn as much as they could in a classroom. Out of the sake of politeness and maintaining family comity, I didn’t say the blunt truth: that they are in fact learning a heck of a lot more, because unlike you, their teacher doesn’t have to stop every four or five minutes and tell kids in the class to settle down. (I had once visited my sister’s classroom, and this was true.) The prejudice she had, and a lot of people have, is that any non-standard form of education has to be substandard.

I doubt Veronique Mintz meant to raise this issue, but it’s one that nobody likes to talk about: what if the problem is not the system, but the kids, and the families that send them to school without the character qualities necessary for their success?

When I was on the editorial board at the Dallas Morning News, my colleagues cared a lot about school reform. Really passionate folks. Once we were doing election season interviews with school board candidates. We had one session between incumbent Lew Blackburn, an African-American man representing some of the poorest school districts in the city, and his challenger. I don’t remember the specific question one of my colleagues asked, but it had something to do with testing, and the district’s very poor results. Blackburn’s response was something to the effect of (I paraphrase), “What do you expect? These kids come from poor families. Lots of them only have one parent. Those with two parents, the mom and dad are often both working long hours.” After the meeting, some of my colleagues were really hot at Blackburn. They couldn’t believe that he was so fatalistic.