Rod Dreher's Blog, page 151

April 23, 2020

Labradoodle Breeder Ketman

The great Polish dissident and exile Czeslaw Milosz, in his 1953 book The Captive Mind, discussed the ketman strategy used by people under communism to cope with their condition. The condition is the “constant internal tension” between what they know to be true, and what the system compels them to say is true. Ketman is what you do to conceal from others what you believe is true, on the theory that to be honest would put one at grave risk.

Milosz identified different varieties of ketman. For example, “professional ketman” is the strategy of a lab scientist who convinces himself that it’s fine to go along with whatever the government says, because that’s how he keeps a measure of freedom to do his real scientific work. That is, he formally assents to the lie, and is seen to assent to the lie, for the sake of being able to do the work that matters most to him.

The most profound form of ketman is “metaphysical ketman,” and it is generally seen in countries with a Catholic past, says Milosz. It amounts to putting one’s belief in a metaphysical order (that is to say, religion) on hold to cooperate with the authorities. Milosz cited as an example Catholics in the Soviet bloc who openly cooperated with the authorities, trying to show themselves to be loyal servants of the new regime, and telling themselves that this is something they can do without truly compromising themselves. The person practicing metaphysical ketman thinks he is preserving himself from “total degradation,” and fooling the devil, but the devil knows exactly what he’s doing.

I am thinking right now of how ketman plays out in our time and place. It comes to mind because I’m revising my forthcoming book this week, and am reviewing the part about ketman. When I wrote the book, I was thinking of the way people who know the “diversity” schemes, the “safe space” ideology, and the lot, are lies, but who maintain their position in the system by pretending that they believe it, and by deploying internal rationalization strategies to live with themselves. I’m talking about people who know that all this talk about “equity” and the like is nothing but a cover for rearranging power, and who hope nevertheless to preserve their role within the new order by pretending to believe in it and serve its principles. I believe that college campuses, major corporations, and mainstream media newsrooms are full of ketman-practicers.

This morning, though, I’m wondering about the forms of ketman that people take to continue within the world of Donald Trump. What prompted it was this news:

On January 21, the day the first U.S. case of coronavirus was reported, the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services appeared on Fox News to report the latest on the disease as it ravaged China. Alex Azar, a 52-year-old lawyer and former drug industry executive, assured Americans the U.S. government was prepared.

“We developed a diagnostic test at the CDC, so we can confirm if somebody has this,” Azar said. “We will be spreading that diagnostic around the country so that we are able to do rapid testing on site.”

While coronavirus in Wuhan, China, was “potentially serious,” Azar assured viewers in America, it “was one for which we have a playbook.”

Azar’s initial comments misfired on two fronts. Like many U.S. officials, from President Donald Trump on down, he underestimated the pandemic’s severity. He also overestimated his agency’s preparedness.

As is now widely known, two agencies Azar oversaw as HHS secretary, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration, wouldn’t come up with viable tests for five and half weeks, even as other countries and the World Health Organization had already prepared their own.

Shortly after his televised comments, Azar tapped a trusted aide with minimal public health experience to lead the agency’s day-to-day response to COVID-19. The aide, Brian Harrison, had joined the department after running a dog-breeding business for six years. Five sources say some officials in the White House derisively called him “the dog breeder.”

Azar’s optimistic public pronouncement and choice of an inexperienced manager are emblematic of his agency’s oft-troubled response to the crisis. His HHS is a behemoth department, overseeing almost every federal public health agency in the country, with a $1.3 trillion budget that exceeds the gross national product of most countries.

A labradoodle breeder. America was facing one of the most critical crises of its entire history, and who did this administration put in charge of day-to-day COVID response? A guy whose previous job was managing dogs screwing for profit.

Hey, the labradoodles Brian Harrison’s business produced are beautiful dogs! But come on. Come on! This is on the same level as the G.W. Bush administration putting a GOP hack whose job was working with Arabian horses in charge of FEMA, and then here comes Katrina.

At this point in the Trump administration’s tenure, though, one hardly notices. One has come to expect it, in fact. Why not a labradoodle breeder in charge of managing the US Government’s response to a deadly global pandemic? Is that any worse than the president’s son-in-law managing anything for the government?

So, my question here is, what kind of ketman does it require for honest conservatives to continue working in, or otherwise supporting, this administration? I’m not talking about true believers here, so if you are a true believer in Trump, stand down; this is not about you.

I’m also not talking about conservatives who know that this guy is a fraud and an incompetent, but are sticking by him anyway for purely practical reasons (e.g., judges, fear of Democratic rule). I was likely to be that guy this November, but the severity of this crisis, and this administration’s handling of it, has made me strongly reconsider.

What I’m talking about is those people, both employees within the administration and supporters of it, who in their heart know how rotten this whole thing is, but who outwardly continue to support Trump. How do they do it? I’m not asking that in a rhetorical sense, e.g., “How do these people live with themselves?!” I’m asking in the spirit of Milosz, trying to figure out the specifics of the mental strategy.

I think people like Dr. Fauci, former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, and others practice, or practiced, professional ketman. Frankly, I am glad that Fauci is doing it, because think of the alternative. My guess is that Fauci recognizes that if he said what he really thought, he would be out of a job, and who knows who would be put in charge of his critical agency in this time of national emergency? Maybe Dr. Oz. Maybe an expert in kitty humping from New Jersey.

I think there is probably some metaphysical ketman going on, though, among Republican regulars. True, they believed in the old Republican Party line, but didn’t the 2016 primaries and election show that GOP voters don’t share the old faith? Now the New Faith is here, and maybe some good can come out of it for conservatism if they, as reliable GOP establishmentarians, work with the administration loyally. Deep down, they know that they are having to affirm things they know aren’t true, and are forced to pretend that the administration is competently running things, and even working hard to “drain the swamp.” But they justify it to themselves by convincing themselves that there is ultimate meaning here, and that they haven’t betrayed their principles at all. Sure, Trump is awful in many ways, but you have to give him credit for breaking new ground, and getting rid of structures that had outlived their usefulness. He’s a man they can work with. These people don’t respect Trump at all, but think that they are somehow keeping their inner citadel unviolated by serving him with stoic dedication.

I am sure Trump has their number, and is not in any way fooled by them. He is a cunning man.

Readers, if you want to talk about varieties of Trump ketman, please do. If you want to talk about forms of progressive ketman, I welcome that. What I urge you to do — and I’m going to approve comments with this in mind — is to make sure you understand what I’m talking about here. Again: I’m not talking about people who are true believers (in Trump, in diversity ideology, whatever), nor am I talking about people who openly admit that by supporting Trump, or [fill in the blank], they are siding with a figure or a cause that is deeply flawed, but which they embrace for purely transactional reasons.

I am talking instead about how individuals navigate the tension between who they really are, and who they pretend to be. I am talking about those people who in their innermost selves believe that the figure or the cause they serve is rotten and unjustifiable, but who outwardly present themselves as true believers. How do they manage the cognitive dissonance?

There are a lot of people who work in ministry or church administration who are well practiced in metaphysical ketman. I’d like to hear from some of you who have practiced this, or seen others practice it. I’ve talked to Catholic priests over the years who are expert in practicing professional ketman vis-a-vis their bishops, believing that if they just pretend to be cheerful team players, they will be left alone to do the work that really matters to them in the parish. What would it be like to descend below professional ketman, within Church government, and to practice metaphysical ketman?

I can think of one case in particular in which I worked with someone who was manifestly incompetent, but who had been hired for diversity reasons. After this person’s utter inability to do the job became clear, I made my views known to my superior, and after that said nothing else. My boss, who I greatly respected, knew exactly what I thought, but my boss also knew that as a matter of professional responsibility, I was going to do my best to be a team player, and help the team succeed. Eventually it didn’t work, and the hire moved on. I did not practice ketman, though, because I never allowed myself to be seen as a supporter of this hire or the ideology that caused it to happen.

Anyway, ketman. Let’s hear what you have to say. Labradoodle Breeder ketman is today’s most exciting form of ketman, don’t you think?

UPDATE: This is a pretty fair complaint by a reader:

This blog entry demonstrates a shocking lack of Christian charity! Brian Harrison perhaps does not possess the administrative and technical knowledge to fulfill the tasks that he was assigned, but it grossly unfair to present him as if he is nothing more than a dog breeder. Without wishing to defend any policy or administrative action, the most cursory examination of this gentleman’s resume reveals that along with breeding dogs, he also “worked in the office of the Deputy Secretary at HHS during the George W. Bush Administration, and has held positions at multiple other federal agencies, including the Social Security Administration, the Department of Defense, and the Office of the Vice President at the White House. He has worked as a director at an independent public affairs firm, helping oversee their healthcare portfolio, and, prior to returning to government, ran a small business in Texas.” Your entire scornful treatment of this man, all of which comes from the “resistance” media, such as Reuters, is neither decent nor fair. Next time, do the Christian thing and look at the entire person before passing judgment in a public forum. By the way, I do not intend this comment to be taken as a defense of the handling of the virus by the administration; rather, it is a reaction to your scorn for this individual, who has apparently had a far more varied career than that of raising dogs.

It’s a fair comment, despite the Christian charity and “resistance media” rhetoric, because I did not realize that this man had a career in public policy before he was a dog breeder. My judgment of him was unfair.

The post Labradoodle Breeder Ketman appeared first on The American Conservative.

April 22, 2020

What Good Is Theology In A Time Like This?

In Britain, the Church of England bishops went beyond what the government required, closing their churches not only to the faithful, but also to their own priests, out of what appears to be a misguided attempt at solidarity. This means that weirdly, the priests could not offer the liturgy for believers watching by livestream. The Rev. Marcus Walker, an Anglican priest at the oldest standing church in London, finally had enough of that. In his comeback sermon, he said:

And so we’re back.

Back here in this ancient church after an exile of three weeks.

It’s worth saying a few words, now, on why we’re back.

The Archbishop of Canterbury and the other Bishops of the Church of England issued a letter, almost a month ago, declaring that churches must shut for congregations – quite rightly, and in accordance with Government guidelines – and for clergy, even for broadcasting from their churches – an activity explicitly permitted within the Government’s guidelines.

After a considerable amount of uproar, on Easter Day the Archbishop of Canterbury clarified that these were guidelines and not instructions, nonetheless using the power and strength of his position to argue in favour of his guidelines.

As the Incumbent of this church, who, with the Parochial Church Council of this church, has the only legal authority to end worship here, I have taken the Archbishops’ guidelines very seriously. I have thought and prayed on them, and listened too to the voices of my flock, of my parishioners, among whom I have been sent to serve and the care – the cure – of whose souls I have been entrusted by the Bishop, with the Bishop.

Their voices have been loud, insistent, and – so far – unanimous. I have received scores of letters and emails, calling on services to be restored here in their church: the church they have upheld and kept up, where they were married, where they buried a partner, saw a child christened, found God, were confirmed.

This is their church and I am their pastor; I owe them my solidarity.

As one said in her letter: “We don’t need you in solidarity at home, we need you in solidarity at the altar of our church.”

And so here I am…

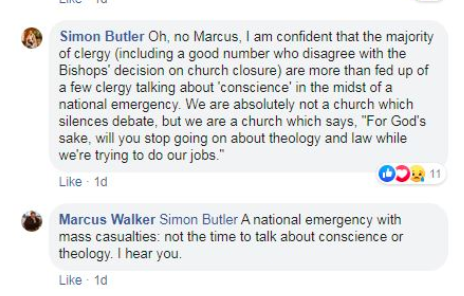

That caused a big social media squabble. Here is an exchange between Canon Simon Butler of the C of E, and the Rev. Walker:

Pow! A TKO for Father Walker! The British historian Tom Holland takes the correct measure of this exchange:

Fascinating how the secularism bred of Christian theology & history now seems to be cannibalising the Church itself. It’s the traditional understanding of its purpose – as a portal onto mystery, an interface with the supernatural – that’s on the defensive. https://t.co/a7sdcf4LJS

— Tom Holland (@holland_tom) April 22, 2020

These exchanges raise a fascinating topic: In a global pandemic, what are churches for?

Let’s talk about that. Here’s what I don’t want to talk about: whether it was the right call for governments or church hierarchies to stop having services that include the public. That is a policy decision that, in fairness, is not unrelated to the question, but that is not really what I’m getting at here. I agree with the Rev. Walker that churches ought to be open for priests to conduct services, and I would even say that churches (Anglican, Catholic, Orthodox, etc.) should be open for private prayer, if the individual church has the means to provide staff to make sure the faithful are maintaining proper social distance. What I want to talk about here is the point Tom Holland makes, about the unique value of the church in a time like this. Connected to that point is what one thinks the church is for during normal times.

Based on what I see here, Canon Butler seems to think that the main purpose of a church is to do good works. (I ask forgiveness if this is not what he really believes; I’m just quoting his social media for the sake of argument.) It is indisputable that that is one purpose of a Christian church. We know from history that the Christians of the early church period distinguished themselves in the eyes of some Romans by caring for those sick and dying from plague, instead of running away. Actually, Tom Holland tells this story in his wonderful book Dominion, and he also tells how St. Basil the Great founded the world’s first hospital.

But as Holland also tells in that same history of Christianity and its role in forming Western societies, many of the social welfare functions performed by churches were eventually taken up by the state. There is still a charitable, social-work role for churches, and most perform that role. But no one in the modern world looks exclusively to the churches to do that work.

For all the health-care good that hospitals and other secular institutions do, they do not, and cannot, provide a sense of mystery and meaning to people enduring this global calamity. Churches can, and should. Holland mentions Gregory the Great. Just last night, I was perusing The Fate Of Rome: Climate, Disease, & the End Of An Empire, a book by Oklahoma University historian Kyle Harper. In it, Harper discusses the role of these natural phenomena, in particular plague and the Late Antique Little Ice Age, in weakening the Empire in the West, and hastening its decline. I had not ever given serious consideration to these factors, to be honest. I found it so interesting that I reached out to Prof. Harper for an interview; we will be talking tomorrow, and I’ll report back in this space.

Anyway, Harper writes about Gregory the Great, the Roman pope from 590 to 604. I know Gregory primarily as the author of the only hagiography we have of St. Benedict of Nursia, who died in 547. For his work, Gregory interviewed monks who knew the saint personally. In his own history, Harper talks about how Gregory led the Western church through a period of great turmoil and suffering from the plague.

Gregory was made pope in 590, following a year of catastrophic floods in Rome, and another outbreak of plague. In addition to organizing relief work, Pope Gregory’s acts included public prayers. Harper writes, “The incipient plague called forth an energetic liturgical response. Gregory instituted elaborate ritual processions — mournful prayer parades known as rogations — to stay the ravages of the pestilence.”

They didn’t work, says Harper, or if they did, their success was only short-lived. We know from Gregory’s writings that he was almost overwhelmed by the natural disasters, and speculated that the end of the world was at hand. Writes Harper, “Gregory’s life spanned an age of climatic deterioration on a par with anything in the late Holocene.”

If a pope, or any religious leader, cannot be counted on to stop natural disaster by his prayers and liturgies, what good is he — or, to be precise, what good are prayers and liturgies? What good is theology at a time like this?

I can think of a couple of answers that should make sense to someone who is not a believer. I’ll stipulate that I believe very much in the efficacy of prayer, but that prayer is not a magical incantation meant to subdue the natural world to the will of the pray-er.

The Chartres cathedral, built in the high Middle Ages, is meant to be a representation of the cosmos entire. In a similar way, liturgies and ritual prayers order experience, and remind us that there is metaphysical meaning woven into the fabric of the natural world. It is not necessarily for popes and priests to tell us that God allowed this flood, this famine, this plague, to fall upon us for this or that reason. But it is their role to remind us, through their preaching and their processions, of God’s presence. In a time of grave natural disorder, the work of God, and the manifestation of His loving presence, continues.

If you aren’t a believer, you will probably see this kind of thing as deception, or self-deception. But people who are suffering, both individually and collectively, need something beyond what rationality can provide, to help them go on. A few days after 9/11, my uncle, a Lutheran pastor on the scene at Ground Zero with the FBI, phoned me and told me that a construction worker had just discover some crossbeams that had embedded itself in the ruins in such a way as to resemble a cross on Calvary. I was a columnist at the New York Post, which is why my uncle called. He told me construction workers on the site, digging for bodies in the twisted metal, were going over to the cross to pray. I went over to Ground Zero and got an interview with a mountain of a man, the construction worker who found the cross. He came off the site and, filthy and stinking of burned debris, he told me how he had led a fire captain whose son had perished in the collapse over to the cross, and they prayed together. You can say that desperate people faced with the overwhelming horror of Ground Zero imposed meaning on a crossbeam that fell in a just-so way — and you might be right. But you would not have had the arrogance to say that down at Ground Zero, to men who were living through that hell. To them, they didn’t expect God to tell them why it happened; it was enough that they believed they had been given a sign that God is with them. It allowed them to carry on with their important work, despite everything.

This is what theology and ritual can do.

Second, through their theological teaching, the clergy help us come to terms with suffering and death. As far as I know, nobody has ever come up with a satisfying theodicy — that is, a good reason why an all-good and all-powerful God allows evil and suffering. Oh, there are theodicies that make logical sense, but no syllogism will persuade a mother mourning her dead child that what happened to him was just. Mary, the Mother of God, lived this out in her own life, and in the death of her Son. But her Son was raised from the dead, and trampled down death. It is the role of priests and pastors to explain this, and the reason for our hope in the face of the great mystery of suffering and evil. You cannot ever really know, in the intellectual sense, why these things happen, but through faith, you can enter into the mystery, and live the mystery.

You know who else helps humans come to terms with suffering and death? Philosophers, poets, and artists. I find it hard to imagine that Canon Butler would tell philosophers, poets, and artists to stand down in a time of global pandemic. True, they will have to do their work behind closed doors, but the calling of priests, who teach theology by word and ritual deed, must be done in public, though certainly it is fair that their work be limited by public health restrictions.

The church has both a social-worker role, and a sacramental role. In the sense I mean, the latter statement is true even for churches that don’t have sacraments; the church’s ministers have a special calling to announce God’s presence, and draw us nearer to Him at all times, especially amid crisis. It is an impoverished understanding of the church and the role of her ministers to think that they have no business talking about theology at a time of mass sickness and death. That is precisely what they should be doing! Again, I think it is perfectly reasonable and just for governments and bishops to stop public gatherings for worship until the plague has passed, but it is not right to silence clergy and cut them off from their rituals, especially if the rituals can be broadcast to the faithful. A church that is deemed useless in an emergency time like this is also useless in normal time. That is something that this apocalypse is unveiling, and not just for Anglicans.

The post What Good Is Theology In A Time Like This? appeared first on The American Conservative.

The Culture War Never Ends

Bari Weiss writes in the NYT today:

But what really takes my breath away is how out-of-touch the daily debates on the internet were — “the discourse,” as some of us were taught to call it in college. Among the things the pandemic has clarified for me is the decadence, as my colleague Ross Douthat has described it, of our old culture war. Many of the battles of the past decade now seem self-indulgent and stagnant; others a waste of time.

I would know. I spent a lot of time in the virtual arena where those fights took place. Could a white novelist imagine a black protagonist? How much can cultures legitimately borrow from one another without it being called stealing? Was a ban on plastic straws actually a critical step toward ending our reliance on the fossil fuel industry?

These now seem to me debates of a world of plenty, not one in which tens of millions of Americans are worried about how they’re going to afford groceries.

This pandemic demands something bigger of all of us. One of the things I hope it ushers in is a culture war worthy of this moment. Because there are fights worth having.

She lists some of them, and she’s right. It’s an excellent column.

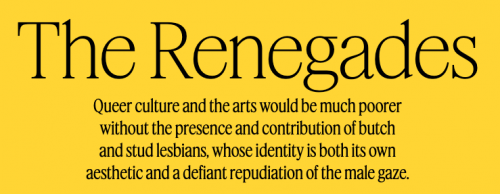

But notice this story, from the same newspaper in the past week, (as pointed out by Patrick Deneen):

You can say that we need a feature celebrating butch and stud lesbians. But you can’t say that while at the same time saying that the culture war has been rendered pointless and obsolete by the pandemic. To be clear, and to be fair, the NYT is a big newspaper, and like any big newspaper, does not tell its writers to take a party line. Bari Weiss is not responsible for the editorial decisions of that part of the paper, nor are they responsible for Weiss’s opinions. Still, it’s interesting to note the contrast.

I too have been thinking about how small our culture war disputes have seemed in the face of the world-historical challenges facing us all. And yet, as James Lindsay reminds us in the interview he did with me, Covid will not kill social justice warriors. Excerpt:

RD: On my more hopeful days, I consider the possibility that this pandemic crisis (including economic collapse) will finally put the SJWs, critical theorists, and the rest, out to pasture. But when I realize how deeply embedded they are within institutions (governmental, corporate, media, academic, etc), I realize that they are going to find a way to use this crisis to their advantage when it is over. What do you think?

JL: The “Critical Social Justice” Theorists, as I have come to refer to them, are activists, first and foremost. You have to understand that. Their primary occupation isn’t being an academic, an administrator, a legislator, an HR director, an educator, or any other such profession you might find them in; it’s being an activist and making their professional role about doing their activism. Once you realize this, your question kind of answers itself, doesn’t it? Of course they’re going to find ways to use this crisis to their advantage. They go around inventing problems or dramatically exaggerating or misinterpreting small problems to push their agenda; why wouldn’t they do the same in a situation where there’s so much chaos and thus so much going wrong. My experience so far is that people are really underestimating how much of this there will be and how much of it will be institutionalized while we’re busy doing other things like tending to the sick and dying and trying not to lose our livelihoods and/or join them ourselves.

It’s very important to understand that “Critical Social Justice” isn’t just activism and some academic theories about things. It’s a way of thinking about the world, and that way is rooted in critical theory as it has been applied mostly to identity groups and identity politics. Thus, not only do they think about almost nothing except ways that “systemic power” and “dominant groups” are creating all the problems around us, they’ve more or less forgotten how to think about problems in any other way. The underlying assumption of their Theory–and that’s intentionally capitalized because it means a very specific thing–is that the very fabric of society is built out of unjust systemic power dynamics, and it is their job (as “critical theorists”) to find those, “make them visible,” and then to move on to doing it with the next thing, ideally while teaching other people to do it too. This crisis will be full of opportunities to do that, and they will do it relentlessly. So, it’s not so much a matter of them “finding a way” to use this crisis to their advantage as it is that they don’t really do anything else.

For the “social justice”- oriented editors and writers at The New York Times, and everywhere in journalism, the pandemic crisis is not an opportunity to step back and reconsider their priorities. It’s an opportunity to keep pushing the agenda while their opponents are busy fighting civilizational catastrophe. And if you object to this, or resist it in any way, they will accuse you of being obsessed with fighting the culture war in a time of crisis.

The diversity bureaucrats at collapsing colleges will be the last ones to go. The Grievance Studies departments will fight like Japanese soldiers making their apocalyptic last stand in the tunnels of Okinawa.

By the way, according to HBO, now is a great time for a reality series in which a trio of drag queens shows up in America’s small towns to liberate the oppressed locals from their tired old values:

We could all use a little love.

#WereHere, a real-life series starring @thatonequeen, @itsshangela, & @eurekaohara premieres April 23. pic.twitter.com/qNGEK8mUmV

— HBO (@HBO) March 20, 2020

See what I mean? It never stops.

UPDATE: A reader sends this meme:

He also sends a link to a 2010 Paul Kingsnorth essay on Roman decadence. He’s talking about decadence in a Douthatian sense. Excerpt:

I wonder if there has ever been a generation, in any civilisation, which didn’t think, to a greater or a lesser degree, that its society was decadent, falling apart, betrayed by hopeless leaders, suffering from a failing system. Perhaps not. But the fact that this may be the case doesn’t disguise another fact: that it is sometimes true. Sometimes societies are noticeably in decline; sometimes a cultural decadence does set in. When it does, ferociously insisting otherwise may become a necessary survival mechanism, but it doesn’t arrest the slide.

This set me wondering about the society I live in. In some ways – ways which we have explored here before – it seems that an inevitable decline is clearly underway. This is the decline of the industrial world: the world that has held sway globally for two centuries. We’ve looked at this in economic and environmental and political terms: climate change, peak oil, ecocide, the collapse of political and economic narratives; the evidence is all there.

It is easy, in some ways, to point to things like climate change, peak oil or deforestation, or even the hardening of the democratic veins with corporate fat, as signs of an imminent collapse or decline, because at least to some extent these things are clearly measurable. But what about more malleable, fuzzy, cultural pointers? What about decadence? Because if decline is real, it should surely be obvious in the culture we make.

The cultural elites who make television hold drag queens up as guides to the moral life. They really do. I saw a clip from this HBO series the other day in which one of the drag queens talked about healing the lives of the small town people to whom they minister. This is also the point of Drag Queen Story Hour, you know: to teach children about diversity and all that.

In the end, there’s no getting away from the fact that we live in a society in which the elites believe that one way to cure the proles of their horrible values is to teach men to dress like caricatures of women, and teach everyone else, especially children, to cheer for that.

” We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful,” said C.S. Lewis, of the modern age. We will not ride out this catastrophe on the backs of these repugnant geldings.

The post The Culture War Never Ends appeared first on The American Conservative.

April 21, 2020

Robert Alost, 1935-2020

Last week, an old man in north Louisiana passed away halfway through his ninth decade. I barely knew him, but like a number of kids who attended the Louisiana School for Math, Science, and the Arts, I owed him so much. It’s hard to think about what my life would have been like had never lived. But he did, and this is what he did for me.

Before I tell you, I’m going to quote from the Facebook post of my friend Sharon Williams, who explains a lot:

I have been encouraged by a dear friend from class of 1985 to share some thoughts about Dr. Alost so here goes…

Bobby Alost, THE founding Director of LSMSA, was an idealist, a visionary, and a man of tremendous drive and physical energy. He conceived of the Louisiana School after hearing a presentation by the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics at a meeting in Hilton Head, South Carolina, but he wanted to do something even better for the state of Louisiana. On the way, he had to gain support of the legislature, the BESE, and two hundred students and their parents with little more than a dream to share.

What follows are excerpts from an introduction I was asked to make when parts of the hsb were dedicated in 2005.

This is an excerpt from a guest editorial Bobby wrote in the school’s first official newspaper, “The Renaissance “, in 1984: “To dream is a simple thing. It takes neither effort nor sacrifice nor dedication. It requires no compromise, no sharing, and no assistance. But to make a dream come true, that is a much greater thing to do.”

In 1982 I received a call from Dr. Alost asking me to come to Natchitoches to talk with him about the school. We talked, walked through the hsb which was a shell and he made the school come alive to me. As an ABD grad student, I eagerly accepted his job offer right there on the spot. I wanted to be a part of helping to start a school. I was a believer from the start. All six of us Bobby hired in 1982 were believers.

We sat about traveling the state and telling a story-a story about a school that didn’t exist (yet); a curriculum that really wasn’t yet formulated; buildings that weren’t ready except in our minds and there it all existed because Bobby had spent so much time telling us of his ideas…how could his dream and now our dream not come true??

I didn’t know enough to be scared or even doubt what we were doing. The school would be a success. Nothing was going to get in our way.

The day came when we finally opened our doors and 200 students from across the state came to share our dream of an ideal high school for high achieving and highly motivated students. We had spread our dream to 200 more people who believed, too.

These 200 students brought Bobby’s dream to reality. Then we had a second year roll around before we knew it and now had 400 students! Bobby inspired in all of us the determination, the heart, the skills, and the dedication to make our school a reality. And we have been sharing his dream since. Bobby’s dream is alive and still growing-his school — it will always be Dr. Alost’s school in my heart — is thriving.

Dr. Alost (Bobby he wanted me to call him which sometimes I could manage) touched so many, many people-students, families, extended families- and has opened an untold number of doors for for alumni. I don’t know if he realized how much it means to me to be a part of his dream…to look back on so many memories-and they’re only good.

He dreamed and believed and we did, too.

That’s really true. I was in that first junior class, which arrived on campus in Natchitoches in the fall of 1983. I have a sixteen year old son now, and can easily imagine how hard it was for my mom and dad to say goodbye to me at that age, and send me off to a residential school 160 miles from home. As my mom has told me over the years, they felt they had no choice. I was so unhappy. The bullying had worn me down. “We thought we might lose you if we didn’t let you go,” she says.

Bobby Alost’s school was not the kind of thing you expect in a poor Southern state: a public boarding school for gifted and talented kids. But there it was, and there a couple hundred of us were, excited, maybe even a little frightened, out at his house in the pine woods, on a lake, on a warm autumn weekend, trying to get used to our new family.

Looking back almost four decades later, one thing that jumps out to me is the difference between us kids who came from big-city schools in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and elsewhere, and kids like me, who came from small towns and rural schools. The city kids took it in stride, but us country kids — man, it was like having emigrated to a land where the streets were paved with gold. I’m serious. To be able to walk down the hallway and not have to worry about some stupid jock or some preppy bitch picking on you, or to have your nose rubbed into the fact that you were a freak and a nerd and you didn’t belong here — my God, what kind of paradise is this? Who knew that high school could be a place where you could let your guard down? That’s what LSMSA was for me, and more than a few of my classmates.

The academics were superlative. This was a high school that taught college-style, and featured classes on Faulkner, Walker Percy, Russian history, and so on. They figured students could handle it, and mostly they were right (don’t ask me about math and science; no kidding, I still have the occasional anxiety dream about those classes). Imagine a school where the teachers didn’t have to spend half their time trying to get students to settle down and listen. Where you were encouraged to ask questions, because nobody was going to make fun of you for being smart. And imagine being in a high school with a pretty diverse set of kids from all around the state, not all of whom would be your friends, but none of whom would be your enemy.

The autumn that I arrived at Bobby Alost’s school was the first time in my life that I felt that I truly belonged somewhere. That I had found my tribe. Dr. Alost, as we all called him, was a big, husky, papa bear figure who was the embodiment of our new home. He was our Big Chief. It’s funny, because he didn’t make a habit of getting too involved in the lives of his students, but then, he didn’t really have to in order to make an impression on us. We all knew that LSMSA existed because he had a dream, and he fought for it, and inspired good people like Sharon to fight alongside him, and to nurture alongside him.

He showed me mercy once. There was quite a drinking culture among high school students in Louisiana back then. Liquor was strictly forbidden at LSMSA, but some of us, being idiots, got our hands on it anyway. One night, at lights-out, the head RA of my dorm found a bottle of beer in my closet. I was sent home for a week in suspension, and deserved it. Well, at some point in my senior year, I was tending a badly broken heart, shattered by the hammer blows of unrequited love, and tending it badly. Depressed and not giving a damn, I went out and bought some booze. The head RA of my dorm caught me with it before I could drink a drop. That was my second offense. I could have been expelled for good, with only a few months till graduation. Had that happened, I would have done it to myself. But Dr. Alost decided to let me stay, when he did not have to. Like I said, I owed him a lot.

It says something about the family that man gathered around him that here we are, almost forty years on, and many of us have lost touch with our college friends, but we still stay in touch with each other, and our teachers and the staff who first welcomed us to Natchitoches. I could be wrong, but I don’t think many of us, if any of us, stayed in touch with Dr. Alost. He left LSMSA in 1986 to become president of the university on whose campus our school sat. Only the first two classes of LSMSA ever knew him, and as kindly as he was, he was also a bit formal, even stately. As we aged, our former teachers and staffers urged us to call them by their first names. We would have died a thousand deaths before calling Dr. Alost “Bobby,” and it wouldn’t have been from a lack of affection.

When I heard last week that he had died, my first thought was to plan on driving up to Natchitoches to pay my respects, as if my own father had died. But then I remembered that this is coronatide, and there would not be a funeral. This is painful. Bobby Alost really was a father to me, in an important way. He set me right, and made it possible for me to believe that life was good, and that I had a future. The last time I saw him was five or six years ago, at a class reunion. He never came to those, but this year he did, and boy, did my classmates all make a point of having a word with him. I tried to thank him for what he gave me, but I had been warned that he might not understand me, because his mind was starting to slip. It was true, alas. But I said what I needed to say, and managed, somehow, to do it without tears.

The tears are coming now, as I write this. I sure did love that old man, and I didn’t realize how much until I thought about the world he leaves behind, and the lives he changed for the better because he had a mind that dreamed and a heart that made that dream a reality. Here’s the thing: he taught kids like me that we could have dreams for ourselves — dreams of going as far as our own hearts and minds could take us. Very few men can make that boast at the end of their lives. Robert Alost could. RIP.

From LSMSA Facebook page, this 1983 shot

From LSMSA Facebook page, this 1983 shotThe post Robert Alost, 1935-2020 appeared first on The American Conservative.

The Pandemic And Our Heimat

As I have mentioned, I’m watching the 1980s German miniseries Heimat. It’s about life in a German village from 1919 until the 1980s. Fifteen hours. I had heard about it for years, but have long been unable to find an English subtitled version. Last week, an Italian film buff friend of mine loaned me his copy, dubbed into Italian, but with English subtitles. It’s irritating to watch German rustics of the early 20th century speaking Italian, but you get used to it. The drama is quite involving.

The thing that has made Heimat (it means “homeland” in German, but German speakers say it’s more intimate than that) so intriguing to me over the years has been the way critics say it changed the way people outside of Germany saw Germans. It came out a generation after the end of the war, and landed (outside of Germany) in cultures where our view of Germany was wholly determined by Nazism. Heimat allowed us to see Germans as just people, like any other, and was quite powerful in that way, or so the critics said.

Having watched three hours, covering the years 1919 to 1933, I completely understand that claim. I don’t think my son, who is 20, and who knows history, would be able to see this with the same eyes as his father. He has grown up in a cultural era in which Germans weren’t portrayed as wholly villainous, at least not in the same way they were during my childhood. I’m at the part in Heimat where Nazism is just starting to take real hold in the village. One of the sons of the Simon family, the main characters of the drama, has become some sort of local Nazi official. Eduard is a good-natured simpleton, for the most part; you can sense that he became a Nazi because suddenly, it was the respectable thing to do to serve your community, like joining the National Guard today. (The village mayor, though, clearly embraces Nazism for darker reasons; you think, when you see this, “Of course.”) The genius of Heimat‘s storytelling is that Eduard’s becoming a Nazi functionary is never explained. He just turns up one day wearing an armband and a party uniform, like it’s the most normal thing in the world. That’s how most others treat him. You get it: there wasn’t any real moral struggle for Eduard in this choice. It was just what people did, becoming Nazis — and for him, it finally gives him respectability and a sense of mission, after having spent the postwar years struggling to find a place for himself. Eduard’s mother is quietly against the Nazis, but doesn’t say anything. All too human.

Eduard’s younger brother, Paul, a World War I veteran, returned from the war shattered. In fact, his return to the village is the opening of the series. When Paul arrives back home, he can’t re-integrate into the village’s life. He fakes it for eight years, marrying and having children. One day, something snaps. He starts walking, and doesn’t stop until he gets to Ellis Island, in New York, as a new immigrant. This isn’t directly explained either, at least not yet in the series, but it makes perfect sense. You think about Paul sitting around his family’s kitchen table, with the other villagers, clucking about the brave local boy just back from the front. You think about how faraway Paul was, and how something clearly had cracked deep inside him, from his experiences on the front. But nobody else saw that, because they were so caught up in village life that Paul’s trauma was invisible to them all. It may have been invisible to Paul too, until the destruction by a wild animal of his beloved radio set, a project that he had been working on for years, broke him.

Because we know what’s coming next, historically — the consolidation of absolute power by Hitler — we understand that the thing that broke Paul and caused him to abandon the village and his family is the same force/event that causes his brother, and many of his countrymen, to abandon their roots and give themselves over to radical political religion (National Socialism).

Why do I bring this all up here? Yesterday reader Lawbooks10 commented:

I continue to be amazed by the parallels of this situation to the First World War. I don’t think most people have wrapped their heads around the enormity of what all this means. I’ve been aware for weeks on an intellectual level, but I work in the oil and gas business, and even though I’m still employed right now, I just today started to really process the fact that my career is probably going to be vaporized. I’m likely looking at long-term unemployment. I continue to believe that this event is the 21st century’s First World War – this event is going to destroy all the assumptions that we have about the world, the future, how our lives will go – comfy middle-class lifestyle, college/career/retirement, etc. If my kid was a junior or senior in high school, am I going to send them off to college to take out debt, or pay for it myself, with this uncertainty? Lord no! And this event is going to accelerate all the pre-existing financial problems we had, with the federal debt and entitlement programs like Social Security, etc.

Not only will the economic fallout be catastrophic, but we lack the social cohesion and individual hardiness to weather it. My grandmother lived on a rural farm in east Texas during the Depression; her family was poor anyways. They didn’t expect to be materially well-off or comfortable. We do. So how we do come to terms with that changing virtually overnight?

I think basically everything is on the table. Here at home, social unrest, rioting, civil war, even the dissolution of the United States. Globally, the collapse of supply lines and trade routes, the largest human migrations in centuries (it will make the 2015 Syrian refugee wave look like a drop in the bucket), chaos in many parts of the world, collapsed states, conflicts over natural resources, etc.

It’s going to be very ugly.

Here’s a portion of a letter I received from a reader last night. He wrote to tell me that he had just lost his job in a Covid-19 layoff:

Now I sit at home trying to read, write, figure out what I do next (looking for work of any quasi-relevancy to my abilities), and not dwell on my bad luck. I graduated into the recession in 2009 (and had to sit out for 6 months to take care of some medical issues, no less), and here a decade later history is repeating itself. I am one of those millennials who fully expects to end his life worse off socio-economically than his parents despite having worked hard, earned a Master’s Degree, never gotten in trouble, etc. For the second time in my life I am brought to financial and professional ruin not because of anything I did, but rather because of the dishonesty and incompetence of others. Will I ever own a house? Will I ever be out of debt? At this point, will I ever be able to afford to have children? Realistically, ehh… I’m not a socialist, but during these once-in-a-lifetime financial meltdowns, of which we have had two in the last decade, I can at least understand the allure. We will all be lucky if we can escape this period without civil unrest, or worse.

Now, you readers know that I am predisposed to decline-and-fall narratives, but I have to tell you, this all resonates very deeply with me, because of all the things I’ve been reading in the past year about the coming of totalitarianism in the 20th century. You know, or should know, that the First World War changed everything. Russia was lost to Bolshevism, and Germany, eventually, to Nazism. Not every nation went to totalitarianism, of course, but none of the major powers who fought that war were left unscathed. There was a radical break with the past in art, literature, and culture. This is all History 101 stuff, but so few people today know anything about that era that it’s worth bringing up here. The war literally shook Western civilization to its foundations, mostly by challenging and demolishing so many beliefs that people previously had taken as certainties. The psychological trauma, especially among the young, was profound. Prior to the war, Europe had lived for a century by the Myth of Progress. It was all shattered by the war (and revived by Communism and Nazism).

Paul Fussell, in his The Great War and Modern Memory, writes:

The day after the British entered the war Henry James wrote a friend:

“The plunge of civilization into this abyss of blood and darkness… is a thing that so gives away the whole long age during which we have supposed the world to be, with whatever abatement, gradually bettering, that to have to take it all now for what the treacherous years were all the while really making for and meaning is too tragic for any words.”

We have not plunged into an abyss of blood and darkness (yet, anyway), but we have plunged into an age of destruction via plague. Now we see what all those years of globalism, technological achievement, and liberation of the individual were making for: a world in which everything can be brought low by a virus. It’s not the same thing as the world war, which, as a wholly moral event (in that people can choose not to go to war, but have no choice about plague), is sharply more tragic. Even so, the advanced civilization and economy we have constructed over the past 50 years, and the highly individualistic society, is ill suited to endure this crisis with resilience.

George Packer has a scorching piece in The Atlantic about how this pandemic has revealed that the United States is a failed state. It’s more on the anti-Trump side than I am — in the sense that he places too much blame for our failures on Trump, when I think the blame is legitimately broader — but he’s not wrong about Trump’s failures, and what they signal. Excerpt:

Like a wanton boy throwing matches in a parched field, Trump began to immolate what was left of national civic life. He never even pretended to be president of the whole country, but pitted us against one another along lines of race, sex, religion, citizenship, education, region, and—every day of his presidency—political party. His main tool of governance was to lie. A third of the country locked itself in a hall of mirrors that it believed to be reality; a third drove itself mad with the effort to hold on to the idea of knowable truth; and a third gave up even trying.

Trump acquired a federal government crippled by years of right-wing ideological assault, politicization by both parties, and steady defunding. He set about finishing off the job and destroying the professional civil service. He drove out some of the most talented and experienced career officials, left essential positions unfilled, and installed loyalists as commissars over the cowed survivors, with one purpose: to serve his own interests. His major legislative accomplishment, one of the largest tax cuts in history, sent hundreds of billions of dollars to corporations and the rich. The beneficiaries flocked to patronize his resorts and line his reelection pockets. If lying was his means for using power, corruption was his end.

This was the American landscape that lay open to the virus: in prosperous cities, a class of globally connected desk workers dependent on a class of precarious and invisible service workers; in the countryside, decaying communities in revolt against the modern world; on social media, mutual hatred and endless vituperation among different camps; in the economy, even with full employment, a large and growing gap between triumphant capital and beleaguered labor; in Washington, an empty government led by a con man and his intellectually bankrupt party; around the country, a mood of cynical exhaustion, with no vision of a shared identity or future.

If the pandemic really is a kind of war, it’s the first to be fought on this soil in a century and a half. Invasion and occupation expose a society’s fault lines, exaggerating what goes unnoticed or accepted in peacetime, clarifying essential truths, raising the smell of buried rot.

This is true. What Packer can’t see, of course, is the decadence of the liberals. Last year he wrote a powerful piece about the identity politics drama in his kid’s New York City public school. The piece was interesting in part for what it revealed about Packer himself: that he’s a good, decent white urban liberal who can’t bring himself to name what is right in front of his nose. He’s like Paul’s family in Heimat, who can’t see the trauma and brokenness borne by their young kinsman, back from the war. The insanity and dysfunction of the public schools in NYC, which, in Packer’s account, are clearly being ruined by left-wing ideology, are a thing that Packer perceives, but can’t name, because to do so would require recognizing that something fundamental in his picture of the world is false.

We conservatives can roll our eyes at the Packers of the world, but we would be wise not to. The faults he finds in Trump, and in the GOP, really are there, to a great extent — and they’re hidden from our own eyes, because to recognize them would mean accepting that the model of the world that we have been carrying around in our head for so long is not valid, or at least not as valid as we thought it was.

I find that I don’t have much patience for anybody, left or right, who doubles down on the narrative that says what’s wrong with America today is the fault of the other side exclusively. Some things are true: that China is primarily to blame for this global crisis, and that the Trump administration has made some particular mistakes that made our response worse. But countries all over the West are struggling hard in similar ways. Spain is in much worse shape than the US, and it is governed by Socialists. In fact, one reason Spain is in so much trouble is the Socialists insisted on going through with the International Women’s Day march, despite warnings that it was too dangerous, in a pandemic time, to bring all those people together. It’s just not true that the failures of governments and societies to deal with this virus effectively are a problem of left-wingers, or right-wingers. It’s a failure of the system, and not just the bureaucracy, but a way of life.

Alan Jacobs has a powerful short blog entry about why so many of us cannot think clearly through this crisis. It has to do with our habits of reasoning in terms of in-groups and out-groups. In this passage, he focuses on the failure of so many of us in the Christian Church to think clearly and respond well, as Christians:

Allow me to emphasize once more a recurrent theme on this here blog: We are looking here at the consequences of decades of neglect by American churches, and what they have neglected is Christian formation. The whole point of discipleship — which is, nota bene, a word derived from discipline — is to take what Kant called the “crooked timber of humanity” and make it, if not straight, then straighter. To form it in the image of Jesus Christ. And yes, with humans this is impossible, but with a gracious God all things are possible. And it’s a good thing that with a gracious God it is possible, because He demands it of those who would follow Jesus. Bonhoeffer says, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” He doesn’t bid us demand our rights. Indeed he forbids us to. “Love is patient and kind,” his apostle tells us; “love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.” Christians haven’t always met that description, but there was a time when we knew that it existed, which made it harder to avoid.

We are unlikely to act well until we think well; we are unlikely to think well until our will has undergone the proper discipline; and that discipline begins with proper instruction.

I’m interested in politics, I’m interested in culture, and I’m interested in economics. But what I really care about is the life of the church. In this crisis, we are seeing essential truths clarified, and buried rot brought to the surface — in politics, in culture, in economics, and yes, in the life of the church. If this crisis is our First World War, in the sense of being a traumatizing civilizational event that radically upends settled ways of living and thinking, then we are all in for a hell of a ride. Politics, culture, economics, religion — none of these things exists separately from the others. Even if you are not a religious person, there are still somethings, or some thing, in your life that you hold to be sacred, and that conditions the way you view politics, culture, and economics. World War I was not supposed to happen, according to the Myth of Progress … but it did, and it recast the entire century.

Think of that nice young middle-class Millennial reader, who now, for the second time in his adult life, is facing his prospects having been reduced to nothing. What does this tell him about his heimat, his familiar world, the “village” that formed him, but that now seems unlivable? Think of Paul Simon, the protagonist of the first part of Heimat, staggering home from the war, to a family and a village full of elders who don’t understand what has happened to their world, and maybe he doesn’t quite understand either.

But he will. They all will. They will see things they can’t have imagined in 1919. We too will probably see things that were hidden from our view in January 2020.

Paul Simon (Dieter Schaad), at home from the war

Paul Simon (Dieter Schaad), at home from the warThe post The Pandemic And Our Heimat appeared first on The American Conservative.

April 20, 2020

Braking News: Church Bus As Deadly Weapon

Cosimanian Orthodoxy has nothing on my boy Tony Spell, the Pentecostal pastor who has made a name promoting himself as a confessor of the faith for urging Christians to defy the stay-at-home order. Look at the, um, braking local news:

NEW: This is video from a neighbor of Pastor Spell allegedly backing up a church bus into the direction of a person protesting in front of his church Sunday. @WAFB https://t.co/GSyfG10e53 pic.twitter.com/cw9rSz52Vi

— Lester Duhé (@LesterDuhe) April 21, 2020

Pastor Spell plays the race card like a champ:

In a telephone interview with WAFB-TV Monday evening, Spell acknowledges he was driving the bus and simply wanted to get out and confront the protestor.

However, Spells [sic] says, his wife, who was also on the bus at the time, talked him out of it.

“That man has been in front of my church driveway for three weeks now,” Spell said. “He shoots people obscene finger gestures and shouts vulgarities.”

“I was pulling in from my bus route, picking up black children who haven’t eaten because of this sinister policy that has closed schools,” the pastor said. “I was going to approach this gentleman and asked him to leave.”

The protestor, Trey Bennett, denies ever using profanity or displaying obscene gestures. Bennett says he has been peacefully protesting in front of Spell’s church since Easter Sunday.

Watch the video and see if it matches Spell’s description of what happened.

O Fortuna! Personally, I don’t think being charged with aggravated assault and being caught on video seeming to attempt to back over a protester with a church bus is going to do much for the Pastor Spell Stimulus Challenge, in which he is trying to convince Christians to send their stimulus checks to churches, including his own.

Uncle Chuckie, have you ever tried to run over your opponents with your AMC Pacer?

UPDATE: A church lawyer tells the Baton Rouge Advocate that the video clearly shows that Pastor Spell didn’t come close to hitting the protester, and that the protester must not have feared that fate, because he didn’t jump out of the way. Local news reporting that as of early Monday evening, the intemperate pastor had not been taken into custody.

The post Braking News: Church Bus As Deadly Weapon appeared first on The American Conservative.

Big Shorts & Failed States

If you don’t think a movie about finance can be a hell of a lot of fun to watch, then you haven’t seen The Big Short. It’s based on the true story of some crazy finance guys who made a fortune betting against the stock market before the 2008 crash. They sailed straight into the gale-force headwinds of the “prosperity forever” psychology, because they had seen fundamental weaknesses in the market that most people missed.

The 2008 crash was the first time I had ever heard of the verb “to short” something, in a financial sense. It means to put yourself in a position to profit if the thing you’re “shorting” fails. It is to gamble on failure. In this fascinating, anger-making piece in the current New Yorker, Nick Paumgarten writes about investors shorting this or that during this current pandemic-driven crisis. Excerpt:

I asked Mohamed El-Erian, the longtime co-chief investment officer at pimco, the world’s biggest bond fund (he now advises Allianz, pimco’s parent company), about the confidence of the Fokkers and the would-be Teppers. “It’s idiotic,” he said. “Well, I shouldn’t use that word. This notion of a V, of a quick bounce back to where we were before—people don’t understand the dynamics of paralysis.”

He said, “This is much bigger than 2008. 2008 was a massive heart attack that happened suddenly to the financial markets. You could identify the problem and apply emergency remedies and revive the patient quickly. This is not just a financial stop. This is infection all over the body, damage to virtually every limb and organ. The body was already so fragile. Those of us who have had the privilege of studying failed states have seen this before, but never in a big country like the United States, let alone a global economy.”

He went on, “In the financial crisis, we won the war but lost the peace.” Instead of investing in infrastructure, education, and job retraining, we emphasized, via a central-bank policy of quantitative easing (what some people call printing money), the value of risk assets, like stocks. “We collectively fell in love with finance,” he said. Apparently, we’re still in love.

Last Thursday, amid news that another 6.6 million Americans had lost their jobs, the Fed announced the infusion of an additional $2.3 trillion, including hundreds of billions to purchase corporate debt, ranging from investment-grade to junk: big dirt. Stocks surged anew. The Fed was propping up risk assets again, at a scale that dwarfed the interventions of 2008, and the bankers were back, hats in hand. They get paid like geniuses, and yet, every ten years, they need bailing out.

Notice the words “failed states.” He’s talking about the US as a failed state. All nations, really. And notice that what the central bankers are doing now is massively larger than the 2008 intervention, which at the time beggared belief. I think that most of us really haven’t come to terms yet with the immensity of what’s happening, in part because we have nothing to compare it to — almost nobody alive today can remember the Great Depression, except as a child. During the Great Depression, the unemployment rate topped out at 25 percent. Nobody knows whether it will get that high in this crisis, but consider this: in the 2008 crash, 8.8 million Americans filed for unemployment; today, 22 million have done so already, and this thing is not nearly over.

Moreover, back then, there were villains: reckless people — bankers, regulators, politicians — pushing easy money. It is somehow easier to cope with psychologically if you can blame somebody, and say with confidence that if ____ and ____, and especially ____ had done their jobs, we wouldn’t be in this mess. Today, the villain is a virus. True, they great global villain in all this is Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party — never forget that. And it is also true that almost no national governments prepared adequately for this crisis. Donald Trump’s maladministration has been particularly lacking, but many other leading industrial countries haven’t fared significantly better. My point, though, is that this is far more like a natural disaster than a man-made catastrophe, as in 2008. I’m not sure psychologically if that buffers the shock better — that, and knowing that the economic pain is necessary to save lives.

Paumgarten ends his piece by saying that truly, nobody knows anything. Nobody knows how bad this is going to get. Everybody’s talking about the astonishing collapse in oil prices today: futures contracts on West Texas Intermediate crude, the American benchmark, went into negative territory, signaling that oil producers will have to pay people to store their oil. With the economy crawling at nothing, and with most people staying home, we’re not burning oil. When it costs more to produce oil than leaving the oil fields alone, they will cease production. In a state like Louisiana, where I live, it is hard to wrap one’s mind around what will happen without oil production, on which so much in this state depends. You might think, “Woo-hoo, cheap gas!”, but the cost of that cheap gas is economic catastrophe for millions. How will the state fund the public health system? The public universities? Road-building? And on and on, throughout every sector of the economy.

And that’s just one industry.

Let’s say the government opens up the economy. Do you really think everyone is going to go back to business as usual with this virus still raging? I’ve written here before about Pastor Tony Spell, the Baton Rouge area Pentecostal preacher who has made a national name by declaring himself a religious liberty crusader. He denied at first that his congregation was at risk of coronavirus, and then said that if the virus came for them, that they would greet death as a “welcome friend.” Well, well, well: last week, the parish coroner ruled that one of Spell’s elderly congregants had died from Covid-19. Spell denounced the coroner as a liar. This past Sunday, attendance at Spell’s cavernous megachurch fell off from around 500 the previous Sunday to 130, according to police monitoring the situation. The pastor denounced police as liars, but the truth is more likely to be that most of Spell’s flock is waking up to the fact that this thing really can kill you.

So, how many people are going to return to bars and restaurants, even if they are allowed to do so by the government, if the risk of sickness and death remains? It’s simply false to assume that the only thing keeping the economy ground to a near-standstill is government policy.

Until and unless we have a vaccine, or at least more effective treatments for the virus-sick, we are going to be mired in economic disaster. Some states will fail. We should not assume, as we magically-thinking Americans often do, that God is going to protect us from history. For decades before his death in 2015, I joked with my dad that I wouldn’t sell the land he planned to leave me in the country, because I would want to have a rural place to live if everything fell apart. Well, for the first time ever, it doesn’t seem like a joke.

What would it mean for the United States to become a “failed state,” do you think? That our government will be unable to meet its obligations, and collapse? That’s what happened to the Soviet Union in the 1990s, which was a horrifically traumatizing time for its people. If you want to understand why so many Russians turned to Vladimir Putin at decade’s end, you have to understand how grueling it was for ordinary people to live through the ruins of Communism’s collapse. Putin consolidated his popularity by going after the post-Soviet oligarchs who enriched themselves amid mass poverty and suffering. Of course he became the biggest oligarch of all, as these figures always do in history. The point is that there is only so much “failed state” that people can put up with before they are willing to back a strongman who promises to put things to right. The kind of people Nick Paumgarten writes about in his piece are not going to be safe in the era to come if they are seen as profiting while the masses suffer.

Or maybe not. Russia still has oligarchs, after all. Maybe the post-pandemic economic future belongs to the smart guys who can figure out which side to short. The scary thing is that when post-Soviet Russia became a failed state, there were plenty of safe places to go, and to put your money: Western countries, which operated under the rule of law. What if the Western states fail this time? Nobody really knows. But given the facts on the table, you’d have to be blind not to see that possibility. And more: the opening quotation of my next book is this, from Solzhenitsyn’s introduction to the 1983 edition of The Gulag Archipelago:

“There always is this fallacious belief: ‘It would not be the same here; here such things are impossible.’ Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth.”

Civilizational order is a fragile, fragile thing.

UPDATE: Reader Lawbooks10 posts:

I continue to be amazed by the parallels of this situation to the First World War. I don’t think most people have wrapped their heads around the enormity of what all this means. I’ve been aware for weeks on an intellectual level, but I work in the oil and gas business, and even though I’m still employed right now, I just today started to really process the fact that my career is probably going to be vaporized. I’m likely looking at long-term unemployment. I continue to believe that this event is the 21st century’s First World War – this event is going to destroy all the assumptions that we have about the world, the future, how our lives will go – comfy middle-class lifestyle, college/career/retirement, etc. If my kid was a junior or senior in high school, am I going to send them off to college to take out debt, or pay for it myself, with this uncertainty? Lord no! And this event is going to accelerate all the pre-existing financial problems we had, with the federal debt and entitlement programs like Social Security, etc.

Not only will the economic fallout be catastrophic, but we lack the social cohesion and individual hardiness to weather it. My grandmother lived on a rural farm in east Texas during the Depression; her family was poor anyways. They didn’t expect to be materially well-off or comfortable. We do. So how we do come to terms with that changing virtually overnight?

I think basically everything is on the table. Here at home, social unrest, rioting, civil war, even the dissolution of the United States. Globally, the collapse of supply lines and trade routes, the largest human migrations in centuries (it will make the 2015 Syrian refugee wave look like a drop in the bucket), chaos in many parts of the world, collapsed states, conflicts over natural resources, etc.

It’s going to be very ugly.

My God, not two minutes ago, I was standing in the kitchen putting on some rice, thinking about a German miniseries I’m watching now, “Heimat,” which starts out in 1919, with the return of a village man, Paul, from the front. By the time the first two hours are over — the narrative takes you through to 1927 — Paul has cracked, and abandoned his wife and young children, and village. But you can tell from the opening scenes, when he arrives back in the village, that something very deep has cracked inside him by what he has seen at the front. Everything that made his life rational to that point has been vaporized. He came unstuck. I was thinking, “What if this is what has now begun to happen to us?” And then I sat down to approve comments, and read that Lawbooks has been thinking of the same thing.

The post Big Shorts & Failed States appeared first on The American Conservative.

Elite Imperialist Crusade Against Homeschooling

This story from Harvard magazine about the evils “risks” of homeschooling has lit up my various networks like nothing else lately. Here’s how it starts:

Rapidly increasing number of American families are opting out of sending their children to school, choosing instead to educate them at home. Homeschooled kids now account for roughly 3 percent to 4 percent of school-age children in the United States, a number equivalent to those attending charter schools, and larger than the number currently in parochial schools.

Yet Elizabeth Bartholet, Wasserstein public interest professor of law and faculty director of the Law School’s Child Advocacy Program, sees risks for children—and society—in homeschooling, and recommends a presumptive ban on the practice. Homeschooling, she says, not only violates children’s right to a “meaningful education” and their right to be protected from potential child abuse, but may keep them from contributing positively to a democratic society.

“We have an essentially unregulated regime in the area of homeschooling,” Bartholet asserts. All 50 states have laws that make education compulsory, and state constitutions ensure a right to education, “but if you look at the legal regime governing homeschooling, there are very few requirements that parents do anything.” Even apparent requirements such as submitting curricula, or providing evidence that teaching and learning are taking place, she says, aren’t necessarily enforced. Only about a dozen states have rules about the level of education needed by parents who homeschool, she adds. “That means, effectively, that people can homeschool who’ve never gone to school themselves, who don’t read or write themselves.” In another handful of states, parents are not required to register their children as homeschooled; they can simply keep their kids at home.

More:

As an example, she points to the memoir Educated, by Tara Westover, the daughter of Idaho survivalists who never sent their children to school. Although Westover learned to read, she writes that she received no other formal education at home, but instead spent her teenage years working in her father’s scrap business, where severe injuries were common, and endured abuse by an older brother. Bartholet doesn’t see the book as an isolated case of a family that slipped through the cracks: “That’s what can happen under the system in effect in most of the nation.”

In a paper published recently in the Arizona Law Review, she notes that parents choose homeschooling for an array of reasons. Some find local schools lacking or want to protect their child from bullying. Others do it to give their children the flexibility to pursue sports or other activities at a high level. But surveys of homeschoolers show that a majority of such families (by some estimates, up to 90 percent) are driven by conservative Christian beliefs, and seek to remove their children from mainstream culture. Bartholet notes that some of these parents are “extreme religious ideologues” who question science and promote female subservience and white supremacy.

And if you weren’t clear on exactly what Elizabeth Bartholet wants:

She views the absence of regulations ensuring that homeschooled children receive a meaningful education equivalent to that required in public schools as a threat to U.S. democracy. “From the beginning of compulsory education in this country, we have thought of the government as having some right to educate children so that they become active, productive participants in the larger society,” she says. This involves in part giving children the knowledge to eventually get jobs and support themselves. “But it’s also important that children grow up exposed to community values, social values, democratic values, ideas about nondiscrimination and tolerance of other people’s viewpoints,” she says, noting that European countries such as Germany ban homeschooling entirely and that countries such as France require home visits and annual tests.

Read it all. There’s not much more to it than that, though. The reporter doesn’t talk to any defenders of homeschooling.

According to the article, Bartholet blames “the Home Schooling [sic] Legal Defense Association” as basically the NRA of homeschooling, calling it an organized lobby that prevents any progress to be made against homeschooling. Erin O’Donnell, the article’s author, gets the name of the HSLDA wrong — it’s Home School Legal Defense Association — but we can forgive her because she was probably homeschooled and doesn’t know any better (/sarcasm). Anyway, if this article doesn’t convince you to join HSLDA (or renew your membership) to protect yourself and your family from what the people at Harvard and other elite institutions have planned for you, nothing will.

Look at the illustration that accompanies the piece (which, to be fair, accurately represents the point of view of the article, which is the job of the illustrator):

That poor little girl, jailed in her home, while other children frolic about. Want to know something funny? That illustration is not the original one that appeared on this article. This tweet captured the original:

Woah.