Rod Dreher's Blog, page 143

May 28, 2020

Trump, Trans, And Second Thoughts

Fantastic news! The reader who tipped me off said, “Now I don’t have to worry about my daughters having to compete against males.”:

Connecticut’s policy allowing transgender girls to compete as girls in high school sports violates the civil rights of athletes who have always identified as female, the U.S. Education Department has determined in a decision that could force the state to change course to keep federal funding and influence others to do the same.

A letter from the department’s civil rights office, a copy of which was obtained Thursday by The Associated Press, came in response to a complaint filed last year by several cisgender female track athletes who argued that two transgender female runners had an unfair physical advantage.

The office said in the 45-page letter that it may seek to withhold federal funding over the policy, which allows athletes to participate under the gender with which they identify. The policy is a violation of Title IX, the federal civil rights law that guarantees equal education opportunities for women, including in athletics, the office said.

Read it all. One more clip from it:

“All that today’s finding represents is yet another attack from the Trump administration on transgender students,” said Chase Strangio, who leads transgender justice initiatives for the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBT and HIV Project.

Well, you might say that. Or you might say that today’s finding represents a defense from the Trump administration of female student athletes from unfair competition. We all know perfectly well that this never would happen under a Democratic administration, certainly not Joe Biden’s:

Let’s be clear: Transgender equality is the civil rights issue of our time. There is no room for compromise when it comes to basic human rights.

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) January 25, 2020

It is no exaggeration to say that Joe Biden wants your student athlete daughter to have to compete against biological males, who are physically stronger and have more endurance. This crackpottery is “the civil rights issue of our time.” This is insane. But that’s where the party is. They don’t even think you can have good-faith disagreement on the issue. There is no room for compromise when it comes to the right of student athletes with bigger bone structure, greater lung capacity, and larger hearts to compete against females, as females, and use their biological advantage to win trophies — and don’t you say otherwise, you hateful bigot!

As regular readers know, I am beyond fed up with Donald Trump. The other day, I wrote in this space that Trump has wasted his presidency on tweeting and starting stupid controversies instead of getting stuff done. A reader wrote to say that from a socially conservative point of view, that’s not really true. He sent this lengthy list of policy decisions by the Trump administration to contradict what I said. It really is quite substantive. Though I still believe that Trump has wasted far too much time, energy, and authority jacking around on social media, that list compels me to admit that I was wrong the other day. This is why it matters to have a Republican president.

Someone also sent me this essay in The Forward by Eli Steinberg, arguing that Trump has been a “warrior for the faithful” who will get Steinberg’s vote as an Orthodox Jew. Excerpts:

I don’t think President Trump is motivated to correct this injustice by his own deep feelings of personal faith, so much as by a desire to align himself politically with people of faith. But that is also very meaningful. And it’s why, despite everything, he will likely win the votes of the faithful overwhelmingly in 2020. It’s why he will get mine.

I did not vote for Trump in 2016. I wrote in “Anyone Else” as a means of protest against the two bad choices we were given. I did not think it was worth taking the chance of allowing Trump to redefine conservatism, and I argued that it was preferable for Hillary Clinton to win than to lose the party to Trump.

I was wrong.

I don’t believe I was wrong in the calculation I made in deciding not to vote for either major presidential candidate in 2016. At that time, it was entirely reasonable to think it preposterous that Trump, who had no history as a conservative, would expend any of his own capital to move the ball forward to that end.

But Trump did. Steinberg says he still has serious problems with Trump, but he says Trump’s clear acts on behalf of protecting religious liberty (e.g., executive orders, nominating judges who care about it) are more important. He goes on:

The President may not have your vote. But if you want to have your electoral way in the future, you would do well to understand why he has mine. You may not want to champion faith communities, but the constant attempt to marginalize us is going to lead us to embrace someone who does.

Steinberg has a point. He’s a reluctant Trump supporter, but a Trump supporter he is, because he knows what it will mean to elect a Democrat, given how hostile the party has become to religious traditionalists.

It might be that all things considered, some religious and social conservatives will conclude that the reasons for voting against Trump outweigh the reasons to vote for him. But there are more reasons to vote for him, in spite of everything, than I realized the other day.

(I remind you all that I am going to spend the rest of the year talking about the good and the bad of Trump and Biden, leading up to the election. For me personally, the question is whether or not Trump represents a threat to the common good great enough to justify voting for the candidate of a party that thinks religious and social conservatives are bigots who need to be suppressed. No matter who wins, I think the country is in for a bad four years. Because TAC is a non-profit entity, I am not going to tell you how I’m going to vote, or even if I’m going to vote in this presidential contest. So don’t even start that with me.)

UPDATE: CNN reporting that GOP political strategists are starting to worry that Trump’s travails are going to drag the party’s candidates down, and they might lost the Senate. Excerpt:

In the four years since winning the GOP nomination, Trump has solidified his position within the party. That has made it harder for Republicans in Congress to distance themselves from him without antagonizing his base. That, say Republican operatives, risks keeping away voters who may consider the GOP but don’t like the President.

“It’s a very, very tough environment. If you have a college degree and you live in suburbia, you don’t want to vote for us,” said one long-time Republican congressional campaign consultant, who added there is a serious worry about bleeding support from both seniors and self-described independent men.

I am a college-educated urbanite who is a conservative, registered Independent, and I very much don’t want to vote for Donald Trump. As a social and religious conservative, this shouldn’t be a hard vote for me: I should be a solid, dependable Republican vote. My state, Louisiana, is almost certainly going to vote for Trump, and neither of our senators, both Republicans, are up for re-election. I don’t know how many conservative voters there are like me, and in a state like mine, it really doesn’t matter. But in swing states, or states with GOP senators up for re-election, the party can’t afford to lose voters like me (even if we don’t vote for Biden, but write in a third party candidate, or stay home). For people with my political priorities, this is about as bad a choice as it gets. Losing the Senate would be a harder blow than losing the presidency. The Republicans might do both.

The post Trump, Trans, And Second Thoughts appeared first on The American Conservative.

Ode To The Roof Koreans

A reader told me he watched this clip this morning. It’s an interview with David Joo, manager of a gun store in L.A.’s Koreatown. Joo used guns to defend his store during the L.A. Riots of 1992. Here’s a short clip of him recalling what that was like. Notice him saying that when the Korean store owners called the police to protect them, they ran away. It fell to him and the others to protect their property:

It prompted my reader to write this poem in honor of the brave shop owners who stood against lawlessness when the LAPD would not. It’s an homage to Macaulay’s “Horatius”:

Ode to the Roof Koreans

But the cashier’s brow was sad,

And the cashier’s speech was quiet,

And darkly looked he out the window,

And darkly at the riot.

“The looters will soon be on us

And the police will hide indoors,

And if those f*ckers win the street,

What hope to save the store?”

Then out spake brave Hyuk Son Lim,

The Owner of the place:

“To every man upon the earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

Defending his own shop

At Koreatown Esplanade?

“Haul down the ladder, Young-ja,

I’m-a going to the roof;

We’re going to-a waste these motherf*ckers

If they try to come and loot

We fled chaotic wartime Seoul

To build a life across the sea

Now who will grab their rifle,

And keep the roof with me?”

Whoever the “Roof Koreans” of today’s Minneapolis are — no matter their ethnicity — may they successfully hold off the mob, whatever it takes. All I need to know about someone politically is whether or not they are on the side of Roof Koreans — that is, ordinary, decent people, of whatever race or religion, who find themselves confronted by a mob that wants to destroy them, with the police nowhere to be found.

The post Ode To The Roof Koreans appeared first on The American Conservative.

Jennifer From Target

Here’s a particularly horrible video from yesterday’s rioting inside the Minneapolis target. Here, the black mob has set upon a white woman in a wheelchair named Jennifer:

In the video, you will hear a woman scream, “She stabbin’ people.” A closer view of the clip at the end of the attack on her shows that she did have a knife. You can well imagine why a woman in a wheelchair caught in the middle of looting would have her knife out. What you might find harder to figure out is what a woman in a wheelchair is doing in a store being ransacked by rioters.

Your first thought is that she was just a shopper who happened to be there when the riot sparked off. Nope. She claimed in a subsequent interview that she was in the store peacefully protesting. Um, really?

She was peacefully protesting against the looters by blocking the door. They beat and robbed her. pic.twitter.com/93pj65tuoz

— Cassandra Fairbanks

May 27, 2020

The Mystical Steve Bannon

To most people, Steve Bannon is a raucous political strategist who (if you like him) helped elect Donald Trump and is working to catalyze nationalist movements, or if you don’t, is an alt-right Svengali paving the way for authoritarianism. What most people miss is Bannon’s deep interest in Traditionalism, also called perennialism, a philosophical school teaching that all the world’s religions teach a version of the same universal truths. For some time, Benjamin R. Teitelbaum has been studying Traditionalism, and Bannon’s connections to politically powerful Traditionalist political insiders. In his new book War For Eternity: Inside Bannon’s Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers, Teitelbaum, a professor at the University of Colorado – Boulder, builds on interviews with Bannon and other key figures to illuminate the ideas held by a surprising network of thinkers and strategists. I recently interviewed Teitelbaum about the book via e-mail.

—

RD: Before we start, let’s define terms. What is Traditionalism, with a capital T? How should the layman distinguish it from small-t traditionalism?

BT: Yes, I wish that the unusual ideas I have been writing had an equally unusual, rather than a deceptively familiar sounding name. Alas… Capital-T Traditionalism is an exceptionally arcane, barely-known philosophical and spiritual school, one of many variants of alternative spirituality you might (might!) find on the shelves of a New Age bookstore. It seeks to uncover truths about the universe through study of and occasionally conversion to the esoteric wings of various religions, most often Sufi Islam and Hinduism. Only secondarily, and only to some of its followers, is Traditionalism also a political ideology. And as a political ideology, its agenda is both vague and grandiose: to oppose modernity and modernism.

I’ll highlight three features of Traditionalism shape its relationship to politics. The first is that Traditionalists believe in cyclic rather than linear time; that rather than progressing from a history of depravity toward a future of glory, societies constantly depart from and then return to their eternal glory.

The second is the belief that virtuous societies are formed around an Indo-European caste hierarchy with a small elite of Priests atop a pyramid descending to Warriors, to Merchants, and finally to a mass of Slaves. When times are good, the hierarchy is intact and the spirituality of Priests reigns, but when times are bad, the materialism of Slaves and Merchants reign and hierarchy itself is dissolved as humanity is leveled into a single mass.

The third principle I will mention is one called “inversion,” through which Traditionalists believe that, when times are bad and humanity is leveled to a lowly mass, we will also start to mistake things for their opposite: what we think is good is actually bad, someone officially devoted to spiritual matters is a slave to materialism, professors spread ignorance rather than knowledge, journalists misinform, artists create ugliness, etc. It is a society of false simulations. Traditionalists claim that we are living in the late stage of the time cycle right now—toward the end of a Dark Age defined by homogenizing materialism and only simulations of virtue, and that only more darkness is going to advance us past the cycle’s zero-point to the rebirth of a Golden Age.

So, when you consider what all of that has to do with small-T traditionalism the way we casually use the term—with someone who likes things the way they were in a given pursuit or concern—there might be some incidental overlap, like a general skepticism toward change or celebration of the past for its apparent orderliness. But the differences between that and capital-T Traditionalism stretch beyond the fact that the latter offers an elaborate explanation for its views: the doctrine cyclic time makes Traditionalists’ pessimism of an entirely different type than Dana Carvey’s “Back-in-my-day” character on Saturday Night Live. For as destructive as change is in the eyes of Traditionalists, they could as well welcomed destruction in a spirit of melancholy and masochism, as a sign that collapse and rejuvenating rebirth are neigh. Put differently, what Traditionalists have, and a grumpy grandparent lacks, is a latent apocalyptica.

RD: Who are the most important historical figures in Traditionalism?

BT: To understand what’s happening today, you really need to know about three figures: Traditionalism’s patriarch was a Frenchman named René Guénon (1886-1951) who died a Sufi Muslim answering to the name Abd al-Wāḥid Yaḥyá. Guénon’s were dense philosophical and religious tracts, condemning individualism and homogenization of society, but otherwise avoiding politics.

It would be a follower of his, Julius Evola (1898-1974), attempted to forge politics out of Traditionalism. Evola was a writer and theorist who imbued the school with explicit racism, anti-Semitism, and sexism (the process of social decline, in his mind, entailed the disappearance of pure Aryans and the loss of masculinist values). But he also thought that decline wasn’t fate, that humanity might be able to push itself backward through the time cycle, and this motivated his attempts to collaborate with Mussolini and Hitler: both seemed to embody an older militaristic modality, he thought, and if only they could be imbued with more spiritual vitality, they could forge authentic Aryan theocracies and travel backwards into a golden age.

A third figure whose visions we less obviously sinister, but who nonetheless created a cult shrouded in suspicion and scandal, was a German/Swiss thinker named Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998), who followed his mentor Guénon in converting to Sufism. His practice and writing came to advocate more syncretism than other Traditionalists, however, fusing Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, and even Native American spiritualities, as well as more idiosyncratic beliefs like sacred nudity and pseudo-erotic propitiation of maternal figures in various religious traditions. But Schuon is as known for the institution he established, a network of Sufi schools—or tariqas—that during the 1970s and 1980s were relatively widespread geographically, with the center being a compound in his adopted home outside Bloomington, Indiana.

RD: What does Christianity have to do with Traditionalism? I mean, there are “Traditionalist Catholics,” which is to say, Catholics who favor the Latin Mass, and who take a dim view of the Second Vatican Council, but that’s not the kind of thing we are talking about with Traditionalism, right?

BT: No, it is generally safe to say that the two are not much closer than small-t traditionalism and Traditionalism, except for one major caveat. Among Traditionalists who are Christians, virtually all are either Eastern Orthodox or Catholic. Part of the justification for treating Catholicism as legitimate are its elements that could be viewed as predating, and transcending, Christ. Its paganism, its hierarchy, its social and theological investment in precedence and continuity, etc.

A similar argument is made in favor of Sufism, that though Sufism is Islamic, it served as a vehicle for preserving archaic, pre-Islamic virtues in Islamized society and therefore could be used to catch a glimpse of what once was.

The problems with Christianity for some Traditionalists, as well as adjacent ideologues in the French New Right, are features that they believe constitute an antithesis of the values they champion: not hierarchy but a leveling and homogenizing universalism communicated in the dogma that Christ’s message is the ultimate and final truth for all people, its teleology and implicit vision of progress bent on transcending a past of sin into a future of salvation, and its embryonic disinclination toward theocracy and endorsement of a secular state contained in edicts to “render unto Caesar.”

I wasn’t surprised when Steve Bannon once told me that, though he is Christian, he doesn’t like evangelism.

RD: Two key contemporary figures in your story are Aleksandr Dugin and Olavo de Carvalho. Most Americans have never heard of either. Who are they, and why are they important?

BT: Both are political operatives who have attempted to shape anti-liberal political leaders in their respective countries, and both have links with Traditionalism.

Aleksandr Dugin is a philosopher/journalist/diplomat and political agitator in Russia. One of the first to translate Evola into Russian, and self-proclaimed devotee of Guénon, he views Traditionalism’s opposition between modernity and Tradition in geopolitical terms, with the West and the United States in particular representing modernity and Eurasia preserving Tradition. Despite never having held a formal position in the Kremlin, he has attempted—in ways at times pathetically ineffective, other times impactful—to advance his vision for containment of Western power and the reassertion of Russian, Chinese, and Iranian influence in global politics. According to U.S. intelligence, he helped facilitate talks between Russia and Turkey after the two came into conflict in Syria.

Olavo de Carvalho only recently gained influence in politics. Born in São Paulo, he was an eccentric astrologer/philosopher who taught university courses and was initiated into none other than Frithjof Schuon’s Sufi Islam tariqa in Bloomington and ran a satellite in São Paulo during the 1980s. He later migrated into becoming a hardline Catholic and renounced Schuon’s organization, even as he continued to write and teach about Guénon.

Following a career as a journalist, a curious move to the United States during the early 2000s, and a burgeoning exposure on social media thanks to his profanity-filled rants against Brazilian politicians, media figures, and academics, he eventually forged a bond with Rio populist Jair Bolsonaro. When in 2018 Bolsonaro won the Brazilian presidency, Olavo and his then-massive social media following were credited as a major contributing factor. He was offered and declined a position as the Minister of Education by Bolsonaro, though he made suggestions as to who could fill some cabinet positions (including Foreign Minister Ernesto Araujo whom I consider an apparent Traditionalist, and who Olavo considers a “more of a Traditionalist than himself”). He maintains intangible but potent influence on the Brazilian president today as an unofficial advisor, and together with those ministers he promoted, constitutes a faction of the besieged Bolsonaro government today.

RD: How does Steve Bannon come into the picture?

BT: To the best of my knowledge, Steve Bannon first met Aleksandr Dugin in November 2018, and Olavo de Carvalho in January 2019. Like them he was a sometimes formal, sometimes informal influence on his local anti-liberal leader, and like them he affiliated with Traditionalism. I never figured out exactly how Bannon discovered Traditionalism (curiously, like Dugin and Olavo, his pathway toward the school went through or near people connected with Armenian mystic George Gurdjieff).

He was raised and continues to identify as a Catholic, of course, but he seems to have had an urge to look beyond standard Catholicism and into alternative spiritualities from a young age: as a twentysomething in the Navy, he knew his way by foot to most metaphysical bookstores in the port cities where his destroyer would dock. The religious thought that he presented to me in our interviews struck me as being much more puzzling and eccentric that that of most Christians, and so was the political profile he would develop later based on his reading of Evola and Guénon.

In my book I walk through his version of Traditionalism, one where he claims to have abandoned Evola’s investment in race and masculinism, keeps the hostility to materialism and modernity, and claims that the final goal of his politics is to allow others to complete a process of spiritual advance—as individuals and as a nation. He still follows the time-cycle doctrine, and even noted to me how this belief diverged from Christianity as he understood it. He attempted to align Traditionalism with American narratives of the self-made-man and social mobility, but the product and its sources are still from a world that would likely baffle, maybe repulse or frighten, your average American Republican.

RD: One thing that really stands out in your book is how Bannon really has tried to get a Traditionalist International going, but has failed. He bounced out of the White House, and hasn’t found his footing since. What went wrong?

BT: Traditionalism really isn’t a political doctrine—it doesn’t outline a political agenda with much specificity, and one of the consequences of this is that political actors claiming affiliation with the school will diverge in their understandings of what they ought to champion. Indeed, the major figures today have quite different understandings of what it means to fight for Tradition and against liberal modernity, how that ought to manifest in politics and geopolitics, and particularly how China, Russia, and the United States ought to be understood.

I reveal in the book how Bannon secretly met with Dugin hoping to persuade him—on Traditionalist grounds—to begin agitating in Russia for a new pro-Western, anti-Chinese foreign policy. Dugin was and remains resistant to the idea. And none of this gets at the deeper issue, that Traditionalism doesn’t really believe in activism, popularity, and in winning a modern political contest. To the extent someone like Bannon tries to build mass sympathy for a political program sufficient to win power in a democracy, he is breaking from the doctrine that would link him with someone like Dugin. So prospects seem bad for the start, though you could say that makes the attempt all the more audacious and volatile.

RD: In the Traditionalist framework, at least as interpreted by Bannon and Olavo, virtue resides in the ordinary people, those shut out from elite circles and institutions. They are supposed to be the repository of true spiritual values. How realistic is this, though, even in Traditionalist terms? In the US, the working class is less religiously observant than the middle class. I understand the trad-populist criticism of the spiritual corruption of the elites, and share a lot of it, but I can’t see solid ground for this valorization of the People. It sounds to me more like an ideological abstraction, the way the Bolsheviks instrumentalized the “Masses,” and the Nazis used “das Volk.”

BT: Yes, in those latter cases you see either a descriptive or a prescriptive vision for treating one part of a population as definitive of the whole. These populations have typically been abstractions and imaginations—the accusation against romantic nationalists, to say nothing of the Nazis, was that they had invented the integral “folk” of the countryside that populated their stories and paintings and songs, just as Marxists had marched off to find a proletariat when such a neatly defined population seldom existed. Most original Traditionalists saw instead the priestly elite as being the “culture makers” of society, the ones who ought shape the masses according to their own ideals.

In Bannon’s and Olavo’s upended version we see something that looks more like standard romantic nationalism à la Herder, where a sector of society deemed most insulated from the corruption of modernity (often rural, less formal education, stationary) was viewed as a vessel for timeless values and identity. And the question to those romantics would be the same to Bannon, and it’s the question you pose: on what grounds do you speak of those people as a whole, and how are you sure they possess the qualities you think they do?

I won’t try to answer that question for them, but I will say that Bannon in particular would likely reject the methods we use to assess who is and is not “religiously observant.” Buoyed in part by his readings of Traditionalism (the concept of inversion I mentioned earlier), and exhibited in his confrontations with the Catholic Church, he is poised to view religious institutions as invalid these days, as simulations of what they ought to be. I don’t think it would be a far stretch to anticipate him thinking that true “Priests” are hidden to institutionalized religion, and to pollsters.

RD: What role do borders play in Bannon’s Traditionalist metaphysics?

BT: Bannon, like Dugin, thinks of borders more expansively than most people. He advocate for the strengthening of national borders, yes, but borders of all kinds are besieged in his mind—borders between civilizations and identities as well as borders within societies governing how people act toward each other and organize their lives.

Borderlessness is a hallmark of modernity, reflected, according to the early Traditionalists, in the disintegration of hierarchy and its replacement by mass, borderless society lacking any collective between the individual and the totality. Reviving borders of all kinds is anti-modern behavior. It is to introduce order where chaos previously existed, and to segment and stabilize the world. This is the common thread motivating Bannon’s social conservatism, his cultural (some would allege ethno-)nationalism, his non-interventionism, economic protectionism, and opposition to immigration.

RD: I happened to be reading your book at the same time as Modris Eksteins’ 1986 history of modernism, Rites of Spring. Eksteins says that just prior to World War I, Germany thought of itself as the champion of true spiritual values, and Britain (as well as France) as exponents of a civilization that placed primacy on money-making and materialism. We know too what the Nazis did with the same general concept. There really are solid historical grounds to worry about a recrudescence. That said, the critique Team Bannon makes of the emptiness of commercial society, and modernity’s capacity to dissolve national and cultural particularity, is both solid and appealing. Can you imagine a way in which political actors could advance the best part of Traditionalism — defending local and national cultures from absorption into the globalist mass — without succumbing to the wicked parts?

BT: Here you are asking me to speak for myself rather than for the people I studied, but I’ll try to work with the question: I think people stand the best chance of deriving something good from Traditionalism when they treat it, not as a guide for action, but instead as a narrative to inspire new analyses of society, which thereafter might function as a basis for action.

In particular I wonder whether there isn’t a place for pondering a chain of correspondences the school proposes, namely, that the most meaningful commonality held by the modern political left and right is their peculiar focus on economics; that the relative disinterest in immaterial aspects of social life might be at the root of our tacit aversion to allowing people and communities to be meaningfully different from one another; that the insistence on building community based on visions of a shared future rather than a shared past—which has so many obvious virtues and which is a near necessity in countries like the United States—underestimates the importance that narratives of a common history play in forging social solidarity.

I think the “wickedness” of Traditionalism comes, not only from the content of the hierarchies it sometimes proposes (race, gender, etc.), and not only from the way it could encourage us to ignore or relish contemporary hardship, but also because of what it doesn’t say—the fact that its grand narrative of human history and the battle of good and bad leaves so much unspecified. Those empty spaces can and have been filled with demagoguery. One way to avoid this is to not subscribe to Traditionalism as religion, of course, but to allow its occasional, qualified insights to live in a wider complex of values and agendas—including those it maligns.

RD: I’ve been corresponding with a national journalist who is trying to understand why some American conservatives (like me) are drawn to Hungary’s Viktor Orban. This journalist is a liberal, and can only see Orban as a villain. I’ve tried to explain that people like me certainly don’t endorse everything Orban does, but we see in him a figure of resistance to George Soros and what Soros stands for. That is, Soros is the epitome of a wealthy, influential globalist who believes localist and nationalist institutions and narratives are problems to be solved. I wouldn’t expect a Western liberal to support a politician like Orban, but tell me, why is it so difficult for Western liberals to grasp that politicians like Orban appeal to deep longings in people — for, as you put it, “community, diversity, [and] sovereignty,” that cannot be reduced to “racism”?

BT: I think it is common to fear complex portrayals of people who threaten you, and the liberal left is certainly afraid of Orban (as am I to an extent, I must admit): his transformation of election processes, his treatment of the media, and his self-proclaimed opposition to liberal democracy, etc. I’m not telling you or your readers anything new in noting how that last piece in particular—Orban’s opposition to liberal democracy—is disqualifying to many Western commentators.

But the added feature here is that he personifies a cause that can appear ascendant in global politics. That prompts some commentators to move from mere criticism to war, and thereby to the realm of us-versus-them thinking, of black and white, of telling people that they are either part of the solution or part of the problem. Muddy those waters with talk of qualifications, contingencies, and parallel interpretations, and—the reasoning seems to go—you can as well be an apologist for the enemy. And when confronted with an unexpected or strange account of someone like Orban—one, say, framing him as a right-wing force for localism and community rather than libertarian individualism—and you’d be lucky to be called “politically incoherent” as Thomas Chatterton Williams recently put it. More likely the instinct will be to accuse you of fashioning a façade to obscure what, allegedly, matters most.

Part of me gets this as a political strategy. I understand theoretically why someone would say that the political stakes are so high these days that a line-in-the-sand tactic might be needed to mobilize. What I want at a minimum, however, is for people to be honest with themselves if they choose this path. I want them to recognize that dividing the world in all-or-nothing terms, adopting and strenuously maintaining uniform definitions of each other and cultivating fear and contempt for inconsistency and the unorthodox constitutes self-imposed ignorance; a subordination of inquiry and knowledge for the sake of political expediency.

RD: Does Traditionalism have a political future? Trump has been useless in actually advancing its goals. In my view, it has been nothing but performative kitsch for him. What will happen to the Trads if Trump wins a second term? If he loses?

BT: I think Traditionalist narratives of Trump could take a number of shapes depending on what happens. Trump’s potential value to these actors rests in his ability to upend the status quo; if he wins and comes to represent a new status quo, then he could soon appear as an avatar of the modernist decadence they loath. Traditionalists’ conundrum resembles that of the standard anti-establishment populist in this sense. But if he loses in November, Traditionalists might retrospectively view his rise as nothing other than a momentary (and prophesied) pause in the cycle of decline, just as Mussolini appeared to Julius Evola after WWII.

But as you can tell, this is mostly about narratives rather than policy. One of the challenges I’ve faced in writing the book is to distinguish when Traditionalism functions as a program for action and when it functions as a lens for interpretation.

Its fatalism—its belief that history is following a schedule and that we find ourselves living toward the end of a dark age and near the dawn of a collapse and rebirth—need not spur much action beyond adopting a celebratory or indifferent attitude in the face of destruction and apparent chaos. That’s not to say that these thinkers can’t identify particular policies that embody their values more than others: the fortification of borders and the shrinking of political spheres is an example of such a cause, and its prospects in a battle against all the forces of globalization seem poor.

But Traditionalists also find encouragement in places we wouldn’t expect. Bannon was quite excited by the short candidacy of Marianne Williamson—a spiritualist Democratic candidate for president who spoke of the need to confront “dark psychic forces.” She seemed to represent a politics of the immaterial, and were she to have faced off against Trump, I’m not sure Bannon would have cared about the outcome, for he might see a larger victory in the entire political spectrum having moved away from materialism.

But your question was not just about Traditionalists, but also Traditionalism.The real impetus to my writing the book was my bewilderment at the fact that a way of thinking so radical and so obscure surfaced suddenly in different positions of power throughout the world. And I still wonder what that says about our present and future. I’m not entertaining the notion that cosmic time cycles and such are actually at play, but rather that the rise of Bannon, Dugin, and Olavo testifies to a broader societal drive to depart from the sociopolitical status quo. For entirely worldly reasons, communities seem to be seeking to dramatic change, and that may keep Traditionalism alive as one of multiple alternatives.

—

[Benjamin Teitelbaum’s book is War For Eternity: Inside Bannon’s Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers (Dey Street Books)]

The post The Mystical Steve Bannon appeared first on The American Conservative.

(Unintentionally) Pro-Trump Riots

In Minneapolis today, civil libertarians expressed their outrage over the police killing of George Floyd by liberating TV sets ‘n stuff from a Target across the street from the Third Precinct:

HAPPENING NOW: Rioters looting Target store in Minneapolis pic.twitter.com/7cdSezUKr0

— Breaking911 (@Breaking911) May 27, 2020

This really builds your civic confidence:

They also looted a liquor store.

Meanwhile, citizens in Los Angeles take out their anger on LA police, who did not kill George Floyd, but who cares about details like that?:

BREAKING NEWS: Black Lives Matter protestors attacking police cars on 101 freeway in LA during #GeorgeFloyd protest @FOXLA pic.twitter.com/iMYnFU2mO6

— Liz Habib (@LizHabib) May 28, 2020

What that officer did to George Floyd was horrifying. All four officers involved in the Floyd incident have been fired. The FBI is coming in to investigate. Trump said today he was going to expedite this investigation. The city’s mayor is calling on the DA to charge the officer who kept his knee on Floyd’s head as he suffocated. What more could be done at this point?

A local Minneapolis TV station featured footage tonight of a black community leader begging with the protesters to stop the violence, and to focus on justice. He’s right. Rioting and looting and attacking police cars is not going to do anything to bring accountability to George Floyd’s killers. If anything, that violence is going to help re-elect Donald Trump.

UPDATE: This went up on Twitter about 9:30pm Central:

Absolute chaos outside the Third precinct. Police are firing tear gas and stun grenades as protesters erect a barricade. Across the street, Target, Cub and other businesses are being picked apart by looters. @StarTribune pic.twitter.com/T7TV30v1lQ

— Aaron Lavinsky (@ADLavinsky) May 28, 2020

Do these businesses and the people who own them and work in them not deserve police protection? What is wrong with the Minneapolis police that they are allowing these lawless mobs to steal from the honest people of that city? Shame!

UPDATE: More bad news from Minneapolis tonight:

Rioters in Minneapolis now targeting another auto parts store. #BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/SaVftFB0FZ

— Andy Ngô (@MrAndyNgo) May 28, 2020

Police are investigating a homicide. They say the owner of a nearby pawn shop shot and killed a person suspected of looting his building.

— Libor Jany (@StribJany) May 28, 2020

Someone brought a chainsaw to the Minneapolis BLM riot. pic.twitter.com/3rF0OXDF1H

— Andy Ngô (@MrAndyNgo) May 28, 2020

These two men say they support the protests but not the riots and are helping protect a tobacco store owner from looting

pic.twitter.com/PDn2Jd8iEB

— Daily Caller (@DailyCaller) May 28, 2020

Well, the cops aren’t protecting businesses, so why not?

UPDATE.2: They sacked a grocery store. Nothing says “we demand justice” like stealing:

Now entering through the back door. Yells of “Free food!” pic.twitter.com/z3728Z6G5J

— Ricardo Lopez (@rljourno) May 28, 2020

… except maybe “burn the auto parts store down”:

The Auto Zone is on Fire pic.twitter.com/2IJHx4AKdt

— Ricardo Lopez (@rljourno) May 28, 2020

Half an hour ago, the grocery store the mob looted was on fire:

The Auto Zone is on Fire pic.twitter.com/2IJHx4AKdt

— Ricardo Lopez (@rljourno) May 28, 2020

The post (Unintentionally) Pro-Trump Riots appeared first on The American Conservative.

Amy Cooper, Race, And Mercy

To summarize my view of the Central Park confrontation between Amy Cooper and Christian Cooper:

1. Amy Cooper was wrong to have her dog off the leash in the park.

2. Christian Cooper was right to call her on it.

3. Amy Cooper ought to have apologized, then leashed her dog. She didn’t. She escalated.

4. Christian Cooper escalated too with a threat — “I’m going to do what I’m going to do, and you aren’t going to like it” — then calling her dog over to feed it something.

5. Amy Cooper then shot into the stratosphere — far beyond proportionality — by having a panic attack and making an explicitly racialized threat to Christian Cooper: to sic the police on him as a black man.

6. The police came and sorted it out without arresting anybody.

7. Christian Cooper (or his sister — I’m not sure) escalated this far beyond what was justified by posting video of the encounter on social media to humiliate and punish Amy Cooper.

8. The social media mob did what it always does: savaged Amy Cooper beyond what was proportional to her offense. She is now jobless, dogless, and if she is still in New York City, is probably afraid to go outside.

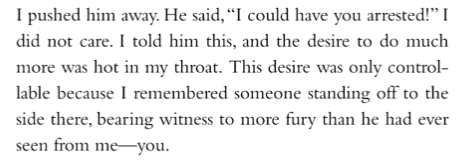

You know what this reminds me of? This incident that Ta-Nehisi Coates related in his megaseller Between The World And Me. He is addressing his son:

So. Ta-Nehisi Coates observes a white woman on an escalator behaving obnoxiously to his kid, but in a way that is (alas) ordinary in New York City. He immediately and instinctively racializes it. Ta-Nehisi Coates does not disclose it here, but he is a tall man. He lashed out at this woman from a place of racial rage (“hot with … all of my history”). A white man who saw a tall man yelling at a woman stood up for the woman — and Coates imputes racism to him (“attempt to rescue the damsel from the beast”). Bizarrely, Coates — who wrote this account years after it happened — can’t figure out why this stranger did not stand up for Coates’s little boy. As if a woman (wrongly!) giving a kid a push (we don’t know if it was a nudge or a harsh shove) and telling him to move on was the equivalent of a grown man screaming at a woman. For all we know from Coates’s account, the white man may not have known what started the argument. What he saw was that a large man was screaming at a woman. And when he confronted Coates, Coates shoved him.

Coates continues:

I came home shook. It was a mix of shame for having gone back to the law of the streets mixed with rage—“I could have you arrested!” Which is to say: “I could take your body.” I have told this story many times, not out of bravado, but out of a need for absolution. I have never been a violent person. Even when I was young and adopted the rules of the street, anyone who knew me knew it was a bad fit. I’ve never felt the pride that is supposed to come with righteous self-defense and justified violence.

Whenever it was me on top of someone, whatever my rage in the moment, afterward I always felt sick

at having been lowered to the crudest form of communication. Malcolm made sense to me not out of a love of violence but because nothing in my life prepared me to understand tear gas as deliverance, as those Black History Month martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement did. But more than any shame I feel about my own actual violence, my greatest regret was that in seeking to defend you I was, in fact, endangering you.

“I could have you arrested,” he said. Which is to say, “One of your son’s earliest memories will be watching the men who sodomized Abner Louima and choked Anthony Baez cuff, club, tase, and break you.” I had forgotten the rules, an error as dangerous on the Upper West Side of Manhattan as on the Westside of Baltimore. One must be without error out here. Walk in single file. Work quietly. Pack an extra number 2 pencil. Make no mistakes.

Think about this. A white woman behaves with minor rudeness to Coates’s child. He escalates it massively, and racializes it. He physically assaults (though in a relatively minor way) a man who tries to defend the woman he is yelling at — and when the man quite rightly points out that Coates has violated the law, Coates interprets this as a threat to use the police to subdue and humiliate him, or worse. And years after it happened, Coates construes this incident as an example of the racial injustice of the civil order in a predominantly white neighborhood. Presumably if the Upper West Side — one of the most liberal neighborhoods in the US — were racially enlightened according to Coates’s standard, enraged black men could yell their heads off at white women in public places, and everyone would stand back and let it happen, to show their racial bona fides.

What’s telling about this incident is that not that Ta-Nehisi Coates behaved that way in public when a stranger treated his kid that way. Most fathers would react with anger; I know I would. What’s telling is that he immediately racialized it, and even years later, rationalizes his own ridiculous behavior. He was not wrong, as he sees it, to blow up at a woman over a minor incident. He was not wrong to bring race into it without justification. He was not wrong to shove a man who came to the defense of the woman at whom he, Coates, was screaming.

Coates only did wrong, in his telling, because he put his son in the position of seeing his father abused by the police. As if the NYPD responds to every altercation involving a black man by using abusive, even fatal, force. A story that ought to have been remembered by him with regret, as a time when he let his emotions get the better of him, Coates renders as a testimony to his status as a victim of white society.

Ask yourself: if a white man had blown up in a public place at that white woman over her minor offense, and had shoved a stranger who came to defend her, who would be seen as the villain of the story? Is there any sense in which a white man could behave that way towards others and be legitimately seen as the victim? Had the Coates role been played by a white man, the woman would have probably told the story as an example of the threat women have to deal with from “toxic masculinity.”

Coates tells this story of himself behaving badly (but still being the victim!) in a book that became a massive bestseller, and won the National Book Award. Coates is a multimillionaire who is now seen as a sage on race in America. After a mild confrontation in a public space, Amy Cooper panicked — why, we don’t know — and wrongly racialized her encounter with a tall black man in Central Park, calling the NYPD on him. Nobody was hurt, thank God; the police let them both go. She was wrong to have done what she did, and she has admitted it, and apologized. But her life is a ruin now because of what happened.

This is not a defense of Amy Cooper, who behaved quite badly. It is interesting, though, to think about how these two similar New York incidents had such radically different effects. Both Cooper and Coates wrongly brought race into an ordinary urban conflict in a city full of edgy people, thus throwing gas on a fire. Coates doesn’t regret what he did, except in a backhanded way, and uses the incident as part of crafting his lucrative public persona on a worldview of unappeasable racial grievance.

I say “unappeasable” because TNC makes it very clear in his writing that he doesn’t expect anything to ever get better in race relations. Forgive me, regular readers, for repeating a story you’ve heard before, but because a lot of people will only come to this post from the outside, not knowing these stories, I have to repeat them here. In a piece I wrote here a couple of years ago, I did a thought experiment to try to understand why he believes the things that he does, even against the evidence. Excerpts:

In this post, I want to think out loud about how and why it is that Ta-Nehisi Coates, a writer and thinker of such sensitivity and promise, gave himself over to racialized despair. Some might say that’s because it makes him a lot of money, and it has brought him immense prestige in liberal circles. But that is unfair. Coates thought and wrote like this before he was rich and famous. I think his wealth and his fame, coming as they have because his racialized despair is very much of our cultural moment, will make it much harder for him to break out of it. Still, it was his before there was money and fame in it, and however blind his race theory makes him to the complexities of American life and American politics, it’s not fair to call him cynical.

I recalled in the post (quoting TNC) how TNC went from being a standard progressive on race, expecting that things will improve over time, to losing all hope that that would ever happen. More:

Reading this tonight, I tried a little experiment in empathy. Is there anything that happened to me that can give me even a little feeling for what this experience was like for TNC? The closest thing I could think of was the four or five years I spent writing about the abuse scandal in the Catholic Church, before I lost my Catholic faith.

The details of that experience are very familiar to longtime readers of mine, so I won’t bore you with them again. But I need to point out a couple of things.

First, TNC described his prelapsarian self as holding this view:

It seemed logical, to me, that this progress would end–some day–with the complete vanquishing of white supremacy.

He set himself up to be disillusioned because he expected of liberalism something it couldn’t deliver. (“To expect too much is to have a sentimental view of life and this is a softness that ends in bitterness.” — Flannery O’Connor). He really seems to have thought that we were moving inexorably to the elimination of that particular evil in this world. And we are! It is absurd to claim that an American black man in 2018 is no better off than an American black man in 1948 (where in much of this country he was subject to lynching), or an American black man in 1848, under slavery. It is impossible to take the claim of no moral progress against white supremacy seriously. In 2008, a black man won the US presidency with 43 percent of the white vote. The idea that white supremacy’s grip on America is as strong as ever is as absurd as claiming that racism is over, because we elected a black president.

My point is, TNC sounds like was once a sentimental liberal who hadn’t yet grappled with the depth and complexity of the evil wrought by white supremacy.

I get that. I was a sentimental conservative Catholic who had no idea what kind of evil I was about to walk into when I started writing about the scandal (in 2001, before it broke big nationwide). Father Tom Doyle, the brave Catholic priest who made his reputation by testifying in court for victims, warned me at the outset that I was headed to a place darker than I could imagine. He wasn’t trying to discourage me at all, but rather caution me to prepare for the worst. I thought I had. I was very, very wrong.

But then, I don’t know what I could have done to make me ready to stare into that particular Palantir and not fry my mind. In time I came to resent, and at times despise, my fellow conservative Catholics who tried to dismiss or denature the scandal with phrases like, “Yes, the American bishops haven’t exactly covered themselves in glory, but …”. The Catholic writer Lee Podles’s book Sacrilege is as close as I’ve ever seen anybody come to recreating and concentrating that extremely painful disillusionment. I couldn’t get past the first few chapters, because it was like reading the Necronomicon. Don’t get me wrong: Podles is a faithful orthodox Catholic, but he told the unvarnished truth, uncovered from his investigation, and from poring over case files. These things really happened. It’s straight hellfire.

The result for me was to be left unable to remain a Catholic. Imagine sticking your hands into an open flame, holding them there for ten seconds, then trying to pick up a Bible with it. The broader effect was to leave me incapable of fully trusting religious authority figures. I don’t even try to do so, not one bit more than I absolutely have to for the sake of practicing my faith. Having seen the extremely perverse lies they can tell to protect their own perceived interests, including the lies they tell themselves, I can’t be party to it. This is not a confession of moral and spiritual strength, but rather one of moral and spiritual weakness.

So: I can see a parallel between my experience and TNC’s. We both held naive faiths in particular institutions and myths — mine in Roman Catholicism and the institutional Catholic Church, and his in Progress, and the institutions of liberal democracy. We both got waylaid by history and the evil that men do, and emerged chastened, even broken.

He has spent the rest of his career writing extremely downbeat, deterministic, fatalistic essays about the unique iniquity of white supremacy, and how it can never be defeated. He has given himself over, in my reading, to a view of humanity that is entirely circumscribed by race. And not just by race, but by a strict reading of racial dynamics in which whites are most themselves when they are evil, and in which blacks, even when they behave in evil ways, do so because one way or the other, they have been made that way by whites.

This is a popular thing to believe nowadays. You can get a MacArthur genius grant for peddling that kind of despair, and win the National Book Award. Still, it’s authentic with Coates.

As a thought experiment, I’m wondering what would have happened to me had I followed his intellectual path from my own disillusioning experience. It’s hard to see a clear parallel, though I suppose it might have been to write books and essays on the evil of organized religion, and how all religion is a scam through which the powerful exploit the weak, or something.

Instead, though I left the Catholic Church, and though I have kept a clear distance from institutional Orthodoxy (I learned from a lapse early in my Orthodox years that I should stay away from church politics), I have not despaired of Christianity. Indeed I have been chastened — severely chastened — by what I learned, but I have also been chastened by my intellectual pride, and my naive idealism. The scandal pretty much beat the religious triumphalism out of me, and it left me with a deep awareness of my weakness for believing certain narratives. I’ve thought a lot over the years about Catholics who saw what I did, who didn’t minimize or dismiss its seriousness, but who kept the faith. Though I’m definitely not returning to the Catholic Church, I think what they have is an important disposition for all Christians to cultivate. I’ve tried to do it within myself.

What helped me was understanding that the same Church, and same tradition, that cultivated within it the evils of the child sex abuse scandal (as well as a long litany of crimes over the centuries) also produced St. Benedict and Dante Alighieri, both of whom came into my broken life bearing grace and good news that healed and gave me hope. The black experience in America has been one of suffering immense evil, but out of that experience came art of astounding beauty and feeling, and prophetic vision. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Martin Luther King Jr. — could any of them have emerged from the kind of despair that has engulfed TNC?

I don’t think anybody can claim that those men minimized or dismissed white supremacy and its wickedness. Somehow, they saw through it, to a deeper reality. They had hope — not optimism, but hope.

In the summer of 2002, I was struggling with rage over 9/11, and on top of that, the sex abuse crisis. My wife begged me to get professional help. On the first day I met with a Christian therapist, he told me that in our work, he was going to help me to understand that under the right set of circumstances, I too could have been piloting one of the planes that the terrorists flew into the World Trade Center. I was furious at him for saying that! No way could I ever be that kind of man. The therapist and I ended our professional relationship after a couple of months over other things, but I still resented him for making such a preposterous claim.

It took me years, but I learned in time that the therapist was right. As I have said here many times, my rage at the 9/11 terrorists led me to rationalize supporting the Iraq War. I didn’t see the Iraqis as people; I saw them as a representative of the people (Arab Muslims) who had caused such murder and destruction to my city and my country. I was part of a culture, professionally and otherwise, that affirmed that rage, and affirmed the response (war) that I was talking myself into supporting, calling it justice.

The thing that is so difficult to convey to others is how little self-awareness I had at the time — and believe me, many, many of us were like that. I was genuinely appalled by the therapist’s suggestion that I could find myself one day in the pilot’s seat of a hijacked airliner. What he was trying to do was to get me to a place where I could forgive, in some real sense, the hijackers, and in so doing free myself from the weight of my rage.

But I was part of a mob, more or less — a mob that was of righteous mind, and that believed by harboring doubts about the proposed war, we were breaking faith with the victims of Arab Muslim terrorism. Whatever else I (and many other war supporters) were, we were not cynics. But we were wrong. People like me were willing to fly the US military into the side of a country, Iraq, that had not attacked us, because some Arab Muslims had attacked us, and therefore any Arab Muslim, in my view, had to pay. That wasn’t what I told myself consciously — but it’s what I believed, deep down. That self-knowledge would come later.

Catholics have reason to claim that I made the same mistake, letting rage overcome my Catholic faith. They could be right. I addressed this above. I am grateful to be an Orthodox Christian, and grateful too to have been freed from my anger at the Catholic hierarchy. But as I said above, recognizing in the aftermath of all that how my passions in the face of real and horrible injustice overcame my ability to think and act clearly forced me to try to approach life differently. A person who is in the grips of passion — even righteous passion — can do terrible things. A mob in the grips of passion is one of the most destructive forces on earth.

I am an emotional person, no doubt about it. The point of growing in maturity, and growing as a mature Christian, is to learn how to master your own passions, lest they master you. I will be struggling in this way until they day I die. All of us should be. One of the great lessons I learned from studying the testimonies of Christian political prisoners under the communist regimes is how even though they were treated unjustly, and even tortured, they never, ever gave in to self-pity, or hatred of their persecutors. How they did this is some kind of miracle — but it is vital wisdom for our time.

In my next book Live Not By Lies, I tell their stories, within the framework of the “soft totalitarianism” coming upon us. What has happened to Amy Cooper is a recent example of soft totalitarianism, and it has nothing to do with whether or not she is guilty or innocent of a moral offense. Under communism, people had to be scared of their neighbors, and of anybody outside of their family or very close circle of friends. You had to watch every word or gesture you made around people you couldn’t absolutely trust, because you never knew if they might be an informant. It completely poisoned social life.

And here we are in 2020, recreating a softer version of this. The state was not involved in the Cooper case, or in the Covington Catholic case, or in any of these cases in which the online mob turns out supposed malefactors based on a viral video (which may or may not tell the truth of what happened in a conflict). But the mob’s actions caused catastrophic real-world effects for real people. What kind of society are we building, when people have to be afraid that what they say in private could be recorded and broadcast to the public, for the sake of causing their own destruction? Or their worst public moments could be captured on video and shared with the entire world — and there will be no redemption for them? I’ll tell you what we’re building: a society that has turned inward out of self-protection, in which solidarity is next to impossible to build, because everyone has to be afraid of everybody else.

And the state doesn’t have to be involved at all.

If we at least tried to live by a Christian ethic, one that elevated mercy and forgiveness, we would be in better shape. Not perfect shape, but better, because we would have an ethic that, if practiced, would call us toward humility and mercy. But we are post-Christian now. Mercy and pity are signs of weakness. Rage is a measure of one’s authenticity. The line between good and evil does not pass down the middle of each person’s heart, as Solzhenitsyn learned in the gulag, but rather, as we see it, between the races, between the secular and the religious, between economic classes, and so forth. We absolve ourselves in advance, and nurture grievance, because we think it gives our lives meaning.

Amy Cooper looked at Christian Cooper and saw — well, what did she see? Did she see him as a real threat? Possibly. Did she see his blackness as a weapon that she could use against him? Absolutely. And in this, she was grievously wrong. He was correct to record their confrontation. To her, Christian Cooper was not a person, but a symbol of whatever she felt was threatening to her — even if it was merely threatening her sense of privilege (that is, the “right” she felt she had to flout the rules of the park). She hoped to be able to cause him harm because of his race. Thank God she failed.

But after it was over, and it had been resolved by the police, Christian Cooper knew that he had in his phone something that could ruin her life: that video. Either he, or his sister (I’m not clear which), made it public. By now, nobody is innocent of what social media mobs can do. Amy Cooper had become in their eyes nothing but a symbol of white privilege and racial animosity. Not a human being, but a symbol. Today, we live in a world in which people of the left and the right alike can be rewarded handsomely for making hate symbols of flesh-and-blood human beings, and causing others to give in to primitive hatred. The President of the United States does it, especially on social media — but don’t for a second believe that he is anything other than a product of this culture. There are leftists who quite rightly denounce him, but who are blind to the capacity for blind, destructive hatred in themselves.

I know this because at one time in my life — from 9/11/2001 until about a year after the war started — I was inside my own version of it.

This petty, nasty woman, Amy Cooper, is professionally and personally destroyed. Go on Google News and type her name in — in the media and online, Amy Cooper is the new Bull Connor. It is extraordinary. She will never recover from this. Could anybody? And now the state — that is, the city government — is getting involved: the NYC Human Rights Commission is planning to bounce the rubble of her life by investigating her, and is reminding her that they could impose huge fines on her. If Amy Cooper has any sense, she will flee the city and not look back.

What she tried to do to Christian Cooper was unjust. But is this justice? Is this the kind of world any of us — white, black, Latino, Asian, secular, religious — want to live in?

I don’t. I want to live in a world in which Brandt Jean are rewarded. He is a black Christian in Dallas whose brother Botham was killed by off-duty white female cop Amber Guyger. She was convicted of wrongful death, and at her sentencing, that young black Christian man, Brandt Jean, gave her forgiveness. He urged her to seek Christ, and to give her life to Him. With the (black female) judge’s permission, he also gave her a hug:

And then, after that was over, Judge Tammy Kemp went into her chambers, brought out her personal Bible, and gave it to Amber Guyger. Watch it here. She told Guyger to start with John 3:16. Guyger hugged her, and said something in her ear. Reporters heard Judge Kemp say, “Ma’am, it’s not because I’m good. It’s because I believe in Christ.”

This black man, Brandt Jean, and this black woman, Tammy Kemp, are heroes of mercy. Because of what they did that day in the courtroom, it is possible, and probably even likely, that the rest of Amber Guyger’s ruined life — a life she ruined by shooting and killing Botham Jean — will be redeemed, and that she will know eternal life. If you are not a Christian, though, I still believe that all of us would prefer to live in a society that esteems the mercy shown by Mr. Jean and Judge Kemp — mercy, even amid the formal administration of justice (Guyger got ten years).

You don’t want to be Amy Cooper. But you also don’t want to be leading the mob that’s tearing her from limb to limb. You want to be Brandt Jean and Tammy Kemp. At least I do. All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. There is none righteous, not one. Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.

This matters, y’all. Brandt Jean will never get a MacArthur grant, or be the object of worship by the cultural establishment. But he is telling us, and showing us, how to live in truth — the kind of truth that will save us from our worst passions, if we want to be saved.

The post Amy Cooper, Race, And Mercy appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 26, 2020

Stoning Karen

You may have seen the video of a 41-year-old New York City woman’s appalling carrying-on in Central Park, when a black pedestrian, a birdwatcher, confronted her about having her dog off the leash in an area of the park where that is not permitted:

The woman’s name is Amy Cooper. The man is Christian Cooper. They are not related. On the video, Amy Cooper appears to call 911, and, hysterical, proceeds to tell the police that an African-American man is threatening her. Christian Cooper posted the video he took of the encounter to his Instagram account, with this telling of what happened before he started filming:

[image error]

The clip went viral. Amy Cooper really does come off horribly. But get this: Now, Amy Cooper has lost both her dog and her job as a banker. She’s professionally ruined now, only a day after this park encounter. The social media pile-on is terrifying, as usually happens in these bizarre cases. She is being excoriated as a “Karen,” the pop culture term for bossypants white women who overreact and police other people’s actions.

But as New York Daily News columnist Robert A. George (a friend and former New York Post colleague of mine) writes, Christian Cooper is the real Karen in this situation. George, who is black, acknowledges that Amy Cooper made an ass of herself:

But Christian did not one of us any favors. He and Amy may not be related, but they’re sure as hell part of the same family of privileged New Yorker. As one Twitter person put, ironically, Christian is the “Karen” in this encounter, deciding to enforce park rules unilaterally and to punish “intransigence” ruthlessly. And how — luring Amy’s dog with dog treats he regularly wears in his handy utility belt? To enforce leash laws?

Exactly! One of the most famous previous Karens was a hysterical white woman in Oakland, Calif., who in 2018 called the police on black people grilling in an unauthorized area of a city park. That Karen was technically correct, just like Christian Cooper. The thing that made the Oakland woman a Karen was making a massive legalistic issue over something that she ought to have just let slide.

In the New York City case, both Coopers are Karens. Both of them behaved snottily, though Amy Cooper’s racialized report to police was especially egregious. Still, it’s not hard to see why Amy Cooper felt ill at ease by Christian Cooper’s behavior. What would you think if you were a woman, and a tall, hostile male stranger said, “I’m going to do what I want, but you’re not going to like it” — and then calls your dog over to himself? For all she knew, he was going to hurt the dog. Well, Christian Cooper may be a Harvard graduate, but he is also black and gay, so he wins the Oppression Olympics over a white woman.

So, yes, Amy Cooper humiliated herself by her rotten behavior, for which she has apologized. That should have been the end of it. But then the shelter came and took her adopted dog away, and the investment bank where she worked fired her. I find this shocking. If it is now a fireable offense for New York City bankers to behave like jerks on their private time, there won’t be anyone left in the industry. She committed no crime. The police came, investigated, and charged no one. And yet, thanks to social media, the obnoxious Amy Cooper has been wrecked.

I know it’s a naive question at this point, but what the hell is wrong with people? Why are people so merciless, and take such pleasure in destroying others? Why do people demand that those we target on social media not be merely shamed, but gutted in every way possible? The mob is absolutely merciless. What the mob is doing is a thousand million times worse than what awful Amy Cooper did in the park. People have killed themselves after being set upon by the social media pack. In Japan this week, the government is considering legislation to curb cyberbullying after the suicide of a 22-year-old Netflix reality show personality. What on earth is to be gained by ripping people apart like the mob does?

Amy Cooper is a jerk who got crossways another jerk in Central Park, and reacted in a terrible way that tripped all the wires. But she is a human being who does not deserve this stoning she’s getting from the mob. No human being would. Yet according to the Social Justice Scriptures, “Thou shalt not suffer a bitch to live.”

I agree with James Lindsay:

In the hopefully unlikely event that Bad White Lady kills herself, we’ll hear this:

She did it to recenter whiteness. The real issue in this case is racist police violence killing blacks, but her suicide would make it about her own suffering. White suicides are political acts.

— James Lindsay, sitting on a hill (@ConceptualJames) May 27, 2020

[image error]

There is no cause worth doing this to a person. None. A mob is a mob is a mob, and the mob is always wrong. If you think you are safe from the mob, you are wrong. Nothing will protect you if it decides to attack you. If you say the wrong thing, and somebody puts it on social media, they can take your job and destroy your life in a single day — and they will — and nobody and nothing can protect you.

Jonathan Kay writes about how Canadian transgender activists set upon Amanda Jetté Knox, a woman who has become popular as a trans ally after writing a popular book about her child and her husband both coming out as trans. What was her crime? Being non-trans, and successful at advocating for trans people. Seriously, that’s what she did. Yes, they called her a “Karen,” which has become the all-purpose term of abuse for white women the progressive mob decides to hate. And after the social media beatdown earlier this month, Knox thought about killing herself, and drove to the emergency room. Knox wrote last week:

I was severely bullied throughout my childhood. In middle school, I was set on fire by two kids in front of a bunch of other kids – just for fun. That’s the most dramatic example of many times confrontation and conflict hurt me deeply, cast me out, and left me scarred. After that incident, I took steps to end my life. A few months later, I went to rehab for substance abuse issues. Ever since, I haven’t been great at dealing with conflict. Add to this grief and a pandemic, and I had arrived in the worst place in my adult life.

“I think I’m having a PTSD episode,” I said to the ER doctor. “I think that’s why it hit so hard and it hurts so much and I can’t get my brain to stop.”

“I think so, too,” he said. “And I’m sorry this is happening. I see you and I hear you. We’re going to get you some help.”

Do we know whether or not Amy Cooper reacted so terribly to Christian Cooper’s prissy policing of the park because she was mentally unwell, or had been traumatized in the past, and was triggered? No, we do not. It doesn’t matter, not to the mob, for whom mercy is a sign of weakness.

UPDATE: Just saw on Twitter that there was a violent mob protest in Minneapolis against the police over the killing of suspect George Floyd. Based on the footage taken of Floyd’s last moments, people have every right to be angry about what the police did to Floyd. But look: the police chief (who is black) has fired the four cops and invited the FBI in to investigate Floyd’s death. What else can possibly be done at this point? Does throwing rocks through the windows of the precinct really make things better? Does vandalizing police cars advance the cause of justice for George Floyd? If the state finds cause to charge one or more of those officers with a crime, then they deserve a fair trial, and if convicted, should go to jail. No good can come of violent mob action.

The post Stoning Karen appeared first on The American Conservative.

Big Journalism Embraces Propaganda Model

You will have seen that Americans have sharply declining trust in the media. For example, results of this April poll:

The headline of that graphic is not quite accurate. Even Democrats’ trust has significantly declined.

If people believe that the media are not playing it straight, trying to be fair, I would direct them to this statement on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” by the Pulitzer Center, which administers the Pulitzer Prizes [UPDATE: I was wrong; the Pulitzer Center does not administer the Pulitzer Prizes — Columbia University does. I apologize for the error — RD]. This is a big deal. It represents the abdication of professional journalism standards, and the adoption of those of a left-wing propagandist. Excerpt:

This is what it sounds like when progressive ideologues in journalism use jargon to talk themselves into embracing left-wing propaganda strategies as a virtue. I remind you that the Pulitzer Prize committee this year awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Commentary to Nikole Hannah-Jones for her role in The 1619 Project, the big New York Times attempt to rewrite the history of the American founding to make it ideologically useful in advancing progressive identity politics.

I remember around 2004, having a conversation with a fellow conservative journalist, about how frustrating it was to deal with young conservatives who contacted us wanting advice about going into journalism as a career. Believe me, if you are a conservative working in the mainstream media, you dearly want to encourage as many conservatives as you can to join the profession, to help correct its many biases. The problem with those aspiring young people, my conservative colleague and I agreed, is that so few of them actually wanted to learn the craft of journalism. They wanted to become journalists as a form of political activism. This is exactly the wrong reason to go into journalism, we thought. So many of the problems of American journalism stem from crusading reporters being more interested in advancing progressive narratives than in telling the complicated truth about life. But at least the liberals, whatever their faults, usually respected the craft enough to learn how to do it well.

Now? I could not in good conscience advise young conservatives to go into journalism, at least not of the mainstream kind. I don’t believe the culture of newsrooms today is reformable. I could be wrong! I haven’t worked in a newsroom for eleven years. But I read and listen to the media all the time, and the kind of biases I routinely saw have gotten worse. Now you have the Pulitzer Center openly abandoning fairness in favor of “expand[ing] and democratiz[ing] our narratives” — Orwellian prog-speak that tells you exactly the kinds of stories they are committing to tell, and the kinds that they will not tell. Some people are more diverse than others, you know.

There is a kind of conservative who thinks that if they just keep pointing out to newsroom leaders the deep inherent biases in their coverage, that the institutions will reform. Does anybody believe that now? Donald Trump may have exploited the mistrust many conservatives have of mainstream journalism, but this wasn’t invented by Trump. Professional journalists are among the least self-aware people around. I remember being at a big national journalism conference back in the 2000s, drinking at the bar with the handful of conservatives in the room, all of us telling stories about the total blindness and bigotry we’ve seen. I’ll tell you, if you have been a minority in a professional space, as conservatives (especially religious conservatives) are in professional journalism, you learn first-hand that there is truth in the oft-heard claim that diversity is important in newsrooms, because it has to do with the kinds of stories we tell. You also learn, though, that most people in journalism see “diversity” as going only one way.

Here’s a 2019 piece I discovered recently by Amanda Ripley, about how journalism can tell stories better. You might think it’s a thumb-sucker of a piece, but it’s actually good, even for non-journalists. She writes about how the standard model of conflict-driven journalism actually does not offer an accurate picture of society’s divisions. Ripley ended up interviewing people who are involved in professional conflict-resolution, and tries to apply the lessons she learns to the journalism craft. Excerpts: