Rod Dreher's Blog, page 145

May 21, 2020

Liberalism & Sacred Order

In a long Twitter thread, Justin Lee — he’s a great follow @justindeanlee — makes a heroic effort to explain to skeptical liberal colleagues at Arc Digital why the critique Patrick Deneen and others make of liberalism should be taken seriously. Here’s the whole thing on Thread Reader. Note well: at the beginning of his commentary, he makes it clear that his focus is metaphysical, not strictly political. By “liberalism,” he doesn’t mean the philosophy of the Democratic Party; he means classical liberalism, the governing philosophy that has ruled the US and Britain since the Enlightenment, and most of the Western world off and on. Free markets, individual liberties, etc.

Lee starts by defining liberty in its positive and negative senses. Negative liberty is freedom from coercion; positive liberty is the freedom to master yourself, and do what you should do. Lee:

Especially in the case of negative liberty, you have to have a state to adjudicate between competing rights — and there’s no coherent way to do that without reference to a set of values outside the system.

Liberalism presents itself as morally neutral, but it’s not, because no political system can be.

There is no escaping metaphysics — that is, an underlying account of the nature of reality. Metaphysics also implies a moral and political anthropology: an account of what a human being is. As Lee indicates, the reason we are having so many problems sorting ourselves out politically is because we, as a late liberal polity, lack a shared metaphysics. The Christian religion used to provide that, but at this point in our history, no longer does, because most people either disbelieve, or their belief is soft and emotional, not strong enough to build a social order on (in other words, Christianity has become subordinated to therapeutic bourgeois individualism). More Lee:

More:

To restate: Lee makes the MacIntyrean point that the attempt to uphold a political order without a shared metaphysics is doomed to fail. He further says that classical liberalism is not possible without Judeo-Christian foundations, because it is from the Bible, and its teaching that man is made in the image of God, that we get the modern idea of human rights. Liberalism’s claim to be neutral is just a pose; it too has a metaphysics, because there is no way to avoid metaphysics.

The ne plus ultra of incoherent late liberalism was this statement by Justice Anthony Kennedy in the majority opinion of the 1992 Casey decision, reaffirming abortion rights:

“At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

The idea that we get to make up our own metaphysics itself implies a metaphysics! Or at the very least it implies an attitude towards metaphysics that is functionally nihilist. The idea that the individual has the right to make it all up is an utterly incoherent basis for a political and social order. You can see in these 28 words the invisible metaphysics of liberalism: it pretends to vindicate a broad idea of individual liberty, but does so in a court decision that judges unborn human beings as outside the realm of personhood. Which, okay, fine — but don’t pretend that you’re neutral here. In fact, this infamous Kennedy line is particularly rich coming from a judge, whose very role is to decide the contours of liberty within a polity.

On the fundamental questions of abortion and gay marriage, the Supreme Court has declared them to be beyond politics. Again, fine, but don’t pretend that this is in any way a neutral decision. Obergefell, like Casey, implies a certain view of what a person is — and in the case of the former, what marriage is. Pro-LGBT liberals think it’s just irrational prejudice when traditional Christians say that gay marriage isn’t really marriage. In fact, though it sounds kind of la-tee-da to put it this way, both sides — pro-SSM and anti-SSM — are operating from incommensurate metaphysics. It’s important to understand that because it shows just how deep the divide goes. Liberals who say it is merely prejudice (or, in the Supreme Court’s judgment, “irrational animus”) are neatly dismissing deep conservative objections based on what marriage is as pure hatred. I bring this up not to start a new argument about gay marriage, but to point out how liberals do this sleight of hand to dismiss conservative claims while reinforcing their own pretense of neutrality.

Most people don’t think metaphysically, of course. That’s not how life works. But we live metaphysically, whether we are aware of it or not. Philip Rieff points out that all civilizations have a “sacred order,” but ours, in the post-Christian era, is the first that has tried to live on a negation of sacred order. It can’t be done — and we are living through the death of a civilization whose traditional sacred order is no longer felt by most of its people. (More on this in a moment.)

The questions before courts now about transgenderism are at bottom metaphysical. What is sex? Is it wholly a social construct, or does it have a strong basis in material reality? I predict the Court will ratify whatever the changing beliefs of the professional class are. This will further damage its authority, because many will see its decisions are arbitrary, as based heavily in an irrational animus towards anything that threatens the educated bourgeoisie.

In any case, I think what Justin Lee is trying to get his liberal friends to grasp is that Team Deneen are writing about something that truly exists. Liberalism is a lot more fragile than many liberals think. Deneen’s basic argument is that liberalism has failed because it has succeeded so well. That is, liberalism has created a world of unprecedented individual liberty, but in so doing, has made society thin, fissiparous, and ultimately ungovernable, because it has left us with no means to adjudicate our disputes. If you want to think more deeply about this, please read this 1989 Atlantic essay by the political theorist Glenn Tinder, titled “Can We Be Good Without God?”

My Benedict Option idea is based on the idea that MacIntyre is right, but that there’s no realistic way to go back to the shared Christian understanding of sacred order. One feature of it that has not been much remarked on by commenters is the claim that even Christians have abandoned the traditional Christian concept of sacred order. I bang on about “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” so much because as Christian Smith has shown, it really is the de facto religion of Americans, including American Christians. American Christianity has failed to Christianize liberalism; liberalism has liberalized Christianity. And by “liberalized Christianity,” I don’t mean only that it has made American Christianity more “liberal” in the sense of “progressive”; I mean that it has rendered Christianity into the religion of liberals (radical individualists) at prayer. You can have a 100 percent Trump voting, God-and-guns congregation that is also 100 percent liberal in the sense I mean. If late liberalism is incoherent, so is Christianity after Christendom.

As a Christian, I am less concerned that the constitutional order continue than I am concerned with the survival of the Church. A superficial reading of The Benedict Option would hold that the greatest threat to Christianity today comes from the state. What I really say in the book is that the greatest threat comes from within: from the unthinking absorption by Christians of classical liberalism and its metaphysics. This absorption has occurred less from a failure of doctrinal instruction and more from a failure of discipleship — that is, instantiating traditional Christian teaching into daily practices.

But I digress. Going back to the Deneen critique, a lot of people faulted him for not having an answer to the problem he diagnosed. That is, because he doesn’t say “this is what should replace liberalism,” then his critique of liberalism must be unsound. This is a failure of logic. If a doctor examined you and said that you have an incurable, fatal disease, what sense would it make to dismiss the diagnosis because the physician does not know how to arrest your condition? That’s what we’re dealing with here. The metaphysics (“sacred order”) of secular liberalism create an unstable and unsustainable political system. There is no apparent way out of this within secular liberalism itself. Something has to give. The fact that for many of us, all the conceivable alternatives to liberalism seem worse than liberalism does not negate the Deneen critique.

In the dawn of the 4th century, Roman paganism was exhausted, but Roman elites could not conceive of anything different than a state founded on the gods that their ancestors had worshipped for many centuries. Within a century, everything had changed. We are in such a time of transition now, I believe. If secular liberals want to understand what’s happening, they need to deal with Deneen (and MacIntyre, et alia), not just dismiss them. If you haven’t read Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed, you really should. He’s a good writer. Even Barack Obama recommended this book as an important read to understand our times.

Anyway, if you’re on Twitter, follow @justindeanlee — he’s consistently interesting.

The post Liberalism & Sacred Order appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 20, 2020

Norma McCorvey, Victim & Grifter

Norma McCorvey, the woman known as “Jane Roe” in the landmark 1973 U.S. Supreme Court Roe v. Wade ruling legalizing abortion, said she was lying when she switched to support the anti-abortion movement, saying she had been paid to do so.

In a new documentary, made before her death in 2017 and due to be broadcast on Friday, McCorvey makes what she calls a “deathbed confession.”

“I took their money and they took me out in front of the cameras and told me what to say,” she says on camera. “I did it well too. I am a good actress. Of course, I’m not acting now.”

“If a young woman wants to have an abortion, that’s no skin off my ass. That’s why they call it choice,” she added.

“AKA Jane Roe,” will be broadcast on the FX cable channel on Friday but was made available to television journalists in advance.

Is it true? Unless there are people from the pro-life side who did this, and who can confirm it, I guess we will never know for sure. The Reuters story (linked above) quotes an Evangelical pastor saying that the pro-life movement exploited McCorvey. He does not say that it was a conscious conspiracy, though — at least the Reuters story does not indicate that. Having not seen the FX program, I can easily imagine that professional pro-life activists saw McCorvey as a “get,” and treated her instrumentally. It was clear in the interviews she did after she came out as “Roe” that she had been beat up pretty badly by life, and might not be the most stable person. Her Wikipedia entry talks about how she was raised by a mother who was a violent alcoholic. Hers was a hard life.

Note well, though, that the pro-choice side will now instrumentalize her posthumously, not blaming her for pimping out her credibility to damage the pro-choice cause. She will be presented as a total innocent who was iniquitously exploited by pro-lifers.

Still, it would not surprise me to learn that some pro-life leaders treated her poorly. This is how political activists can be. They learn to see the world entirely through the lens of their cause, and whether they mean to or not, come to judge people by how useful they are to the cause.

I remember being a reporter on Capitol Hill during some hearings in the early 1990s on partial-birth abortion. One pro-life activist with whom I was personally familiar knew that I was a pro-life Catholic, and sympathetic to the cause. In the House hearing room, before testimony started, she ran up to me with a plastic model of an unborn baby, put it in my face, and shoved a small pair of medical scissors into the back of its neck. She was demonstrating what partial-birth abortion does. I told her to get out of my face. She seemed shocked by that. It wasn’t that I disagreed with her position — I did not, and she knew that I did not. It was that she was so worked up by the horror of partial-birth abortion that she had lost perspective on how to behave there in the committee room. The righteousness of the cause overwhelmed her.

I’ve seen this kind of thing in all kinds of activists, left and right, over the years. Again, it is possible that some pro-life leaders coldly chose to exploit McCorvey. Again, I think it more likely that it was unconscious. That doesn’t make it right, but I think this kind of thing is common in the world of political activism. I do know, though, of one pretty hardcore pro-life activist, a Christian who had no scruples about deceiving pregnant women about his crisis pregnancy centers. Other CPC workers distanced themselves from him, because they knew he was dishonest, and they were afraid that he would hurt the reputations of all CPCs. This guy believed that the cause justified anything. Eventually he got in trouble over his deceit.

I wonder, though — and maybe the FX show gets into this — what McCorvey expected from the pro-life movement, and what she had a right to expect. Did she want all her bills paid? Did she want a permanent job? What? Was McCorvey ever a real pro-lifer? Her Wikipedia entry reveals that she has a history of lying about things related to abortion. Did McCorvey change her mind about abortion near the end of her life, and decided to distance herself from her pro-life activism by inventing an allegation against her former allies?

McCorvey was an unreliable narrator — but the pro-life movement ought to have known this when it embraced her. Her life and testimony were an unstable foundation on which to base activism. Pro-choicers eager to embrace her posthumously, on the basis of her “deathbed confession,” should be wary. They won’t be, because the narrative that McCorvey provided the filmmakers fits what the media want to believe about abortion and the pro-life movement.

Still, there probably are some important lessons for pro-lifers to learn from the sad, confused life of Norma McCorvey. I had forgottten, until I read it on the Wikipedia page, that Operation Rescue leader Flip Benham had McCorvey’s backyard 1994 baptism filmed for a TV show. That right there shows bad faith: something as intimate as a baptism ought not to be fodder for activism.

McCorvey later returned to the Catholicism of her childhood, and was confirmed as a Catholic by Father Frank Pavone, the pro-life activist priest. Pavone, who has himself arguably gone too far in his own pro-life activism, spoke to Catholic journalist J.D. Flynn about the new McCorvey claims. Excerpts:

As to charges that McCorvey was used by the pro-life movement, Pavone said that from his perspective, “I’ve never subscribed to the idea that the pro-life movement used her.”

The priest conceded, however, that “one would have to say that, as in any movement, when there’s a convert, you’ve got to be careful not to put them into the lights and the cameras before they’ve had the healing that they need.”

McCorvey was often thrust into situations for which she wasn’t ready, he said, as she also had been during her alliance with abortion advocates, and that caused her considerable hardship.

Pavone says that McCorvey had trouble paying the bills over the years. He adds:

Pavone said that in his view, McCorvey struggled in her final years, especially after a move from Dallas to Katy, Texas.

“In that final year, she was outside of the support network that a lot of her friends were providing in Dallas,” he said.

You could say: outside of that support network, Norma lost perspective, and became embittered at her pro-life allies.

You could also say: outside of that support network, Norma finally saw the truth, and admitted it.

Only Norma McCorvey knew the real truth. Or did she?

Just this morning I was talking with a friend about someone we know who had a traumatic childhood, and whose accounts — even contemporary stories — about others are unreliable, because this person, X., has a habit of rewriting the past in ways X. requires to feel okay in the world. Like McCorvey, X. was raised by a violent alcoholic parent. I was telling my friend that if X. were hooked up to a lie detector and told a story that was provably false, X. would probably pass with flying colors because in my experience, truth, to this tormented soul, is whatever helps X. sleep at night.

Was it like that with Norma McCorvey? I bet it was. Childhood trauma is a hell of a thing. I don’t say that to take moral agency away from McCorvey, or to run interference for pro-life activists who may have taken advantage of her. I do think, though, that the story of her life is not redemptive, any way you look at it. She presented herself as a pro-life advocate from 1994 until her 2017 death. If she lied to the world about her true abortion beliefs for nearly a quarter-century, and only told the truth when she knew nobody could hold her accountable for it (that is, for a film she knew she would never live to see released), then that is disgraceful.

I’ll leave you with this. Washington Post writer Monica Hesse says that the messiness of McCorvey’s life doesn’t suit either the pro-life or pro-choice narrative. Excerpt:

The activists on both sides who knew her found her charming and found her maddening. She rewrote stories into fantasies. She could be mercenary, and always needed money. Maybe the best word for her was “survivor,” multiple people decided independently. After a rough life, she’d now do whatever it took to survive. At one point in the FX documentary, she chuckles that she’s always “looking out for Norma’s salvation and Norma’s [butt].” At times, she seemed to be exactly what their movements needed. At times, she seemed hellbent on complicating an issue that they found to be absolutely simple and clear.

This made her the perfect Jane Roe, the perfect figurehead of the abortion issue, because it wasn’t simple for a lot of people. Antiabortion activists with accidental pregnancies suddenly find themselves calling Planned Parenthood, convinced that their situations are exceptional. Pro-choice women who terminate pregnancies can move through unexpected grief. At various points in her life, Norma McCorvey represented the issue in all of its complexities and untidiness.

This also made McCorvey a difficult Jane Roe, because movements want their heroes to be pure.

Sounds like she was both a victim and a grifter. Both can be true at the same time.

Here, by the way, is the trailer for the FX documentary:

UPDATE: Good comment from reader Hosanna:

I found this Vanity Fair article from 2013 about McCorvey helpful for having a greater context about her life and person: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/politics/2013/02/norma-mccorvey-roe-v-wade-abortion

This article confirms that McCorvey did receive money for her activism – and, indeed, that one constant theme of her life is that she was always fixated on making money from her centrality in Roe v. Wade. (“She just fishes for money,” the pro-life pastor Benham is quoted as saying.) This was true both in her pro-choice activism days and her pro-life activism days. Given her continual struggles with poverty, I’m not sure she ever saw a path to survival for herself that didn’t involve exploiting Roe v. Wade in one way or another. Note that the Vanity Fair author mentions that he tried to schedule an interview with McCorvey, but that she refused to speak without a $1000 interview fee. McCorvey was almost certainly paid for her participation in this new documentary; was she just saying what she thought the documentary filmmaker wanted to hear, as she said what pro-choice and pro-life activists wanted to hear?

Ultimately, despite the framing the reporting about this documentary is leaning into, I don’t think the story is that cynical pro-life activists knowingly bribed McCorvey to lie. Rather, it’s that McCorvey was a messy woman who sought to make a living from her accidental centrality to a major societal controversy, and pro-choice and pro-life activists alike tried to overlook her messiness in using her as a symbol for the righteousness of their cause. My takeaway is to be wary of using personal stories as arguments – they’re very powerful on an emotional level, but the messiness of reality tends to get sanded off in service of the grand narrative we want to tell. As a servant of the God of truth, a God who thankfully shows grace even to messy people, I want to be faithful to truth – not what I wish the truth was, but truth as it actually is. Only by facing the truth about my own continual mess can I be receptive to God’s grace, and so I must face the truth about other people’s messes in order to be a true minister of God’s grace to them.

The post Norma McCorvey, Victim & Grifter appeared first on The American Conservative.

Ronan Farrow Discredited

Well, well, well, the Golden Boy flew too close to the sun. Earlier this week, Ben Smith at The New York Times published a long piece questioning in detail the reporting Ronan Farrow has done on the #MeToo story. Smith’s basic allegation, which he strongly supports, is that Farrow allowed his crusading agenda to trample over basic journalistic ethics, leading him to report things that either weren’t true, or that he did not establish as true — but which boosted his narrative.

Well, one of Farrow’s victims, former Today Show host Matt Lauer, finishes the wounded Farrow off with a devastating critique of Farrow’s reporting that brought him (Lauer) down. Lauer, who admits to having had an extramarital affair with an NBC employee, said that the subsequent allegations (by that employee, Brooke Nevils) of rape against him — allegations accepted and repeated without challenge in Farrow’s book — were false, and provably false, though Farrow didn’t want to hear that. The column is a devastating series of excerpts like this:

Ronan suggests that Brooke Nevils’ accusations against me are valid, because he writes:

Nevils told ‘like a million people’ about Lauer. She told her inner circle of friends. She told colleagues and superiors at NBC. She was never inconsistent and she made the seriousness of what happened clear.

Does Ronan offer any proof of this claim? Does he say he confirmed this story with any of the friends or colleagues she claims to have told about the “seriousness” of what she now alleges happened in Sochi? Does he include a single comment or quote from a corroborating source for these claims?

No, he does not.

He writes:

When [Brooke] moved to a new job within the company, working as a producer for Peacock Productions, she reported it to one of her new bosses there. She felt they should know, in case it became public and she became a liability.

Does he write that he tried to track down that superior at Peacock Productions? (Which, it should be noted, is completely separate from the Today show.) Did he include a quote or a comment from that superior?

Did he find out if that superior had, in fact, been told about the “seriousness” of what Brooke now claims?

No, he did not. How do I know that? Because I did.

It took me 15 minutes to find out who that “new boss” was. I then contacted Sharon Scott, who ran Peacock Productions at the time Brooke was hired there. Sharon, concerned that she might not have been made aware of a serious situation involving a member of her staff, contacted Brooke’s direct superior. They spoke at length.

That new boss told Sharon Scott that, one night, Brooke simply started talking about having an affair with me. She said, most importantly, that Brooke never said a single word about this being anything but a consensual affair. She said Brooke, in no way, conveyed “the seriousness” of what she now claims. There was never a mention of assault or rape. She says she considered Brooke a friend and Brooke told the story the way someone would gossip with a friend. She told Sharon Scott that there was nothing in what Brooke told her that made her feel it was necessary to contact anyone in management about any concerns.

This superior also stated that Ronan Farrow never reached out to her to confirm the story that referenced her in the book.

Read the whole thing. It is long, and it is full of things like that: instances in which Lauer did what Farrow should have done, which is track down people who could confirm or deny his narrative. Farrow’s fact checker for his book Catch And Kill said that he checked all the claims in the book. It couldn’t possibly be true. I dunno, but it seems like Lauer has quite a lawsuit against Hachette, the publisher of Farrow’s book.

Remember when Hachette canceled Woody Allen’s memoir at the last minute after its existence ticked off Ronan Farrow? The book found another home. I bought it and read it simply out of a principle of solidarity with a canceled author. The memoir was uneven, but I tell you, thinking back now, in light of the Ben Smith and Matt Lauer pieces, to Allen’s detailed story about the abuse allegations, and how it contradicts the Farrow family narrative — in particular, the narrative Ronan has offered — makes me think that nothing this kid Farrow says should be believed. He’s clearly quite a journalistic talent, but he has destroyed his own credibility by his crusading, and by being helped along by journalists and publishers older than him, who ought to have forced him to do his job. Instead, they found a narrative they liked too, and went with it.

Lauer ends:

In an effort to promote one of his Catch and Kill podcasts several months ago, Ronan tweeted the following:

“None of my reporting would be possible without fact-checking”

After investigating Ronan’s journalistic efforts myself and reading the recent reporting on him in The New York Times I think that statement falls quite flat.

The examples of shoddy journalism I’ve explored here are the tip of the iceberg. They are only some, of the many instances I could have cited from the two chapters of this book about me. Maybe others will now begin to ask more questions about the 57 chapters of this book I haven’t touched on here.

Will anyone hold Ronan Farrow thoroughly accountable? I doubt it.

Probably not. Farrow’s narrative is too important to too many elites. But who knows? Maybe there will be some justice. There is already some justice in knowing that going forward, anything that appears under Ronan Farrow’s byline will be disbelieved. This is not like making an honest mistake from sloppy reporting. As Lauer and Smith detail, Farrow did this over and over and over, and all his “errors” were the result of his confirmation bias. As a journalist, this is an occupational hazard. That’s why professional standards exist. The questions that need asking now have to do with why so many older, more experienced journalists and publishers who were responsible for giving Farrow an audience failed. I believed everything I read from Farrow in The New Yorker, because the New Yorker is a gold standard in journalism.

Was.

Ben Smith, in his takedown published in the Times, writes:

Mr. Farrow, 32, is not a fabulist. His reporting can be misleading but he does not make things up. His work, though, reveals the weakness of a kind of resistance journalism that has thrived in the age of Donald Trump: That if reporters swim ably along with the tides of social media and produce damaging reporting about public figures most disliked by the loudest voices, the old rules of fairness and open-mindedness can seem more like impediments than essential journalistic imperatives.

Yes. You don’t have to think that Harvey Weinstein and Matt Lauer (two of Farrow’s victims) are choirboys to believe that they deserved fairness. And let me point out here that for you readers who yelled at me for not reporting years earlier that I knew Cardinal McCarrick was an abuse: this is why I didn’t report it! I was certain that it was true, but I could not verify it by normal journalistic standards. Therefore, it would have been irresponsible to publish. McCarrick was and is a great villain, and I knew this about him in 2002. I wanted worse than anything to take him down. But professional journalism standards exist for a good reason — as Ronan Farrow’s disgrace reminds us.

UPDATE: The leftist journalist Glenn Greenwald weighs in on Ronangate. Excerpt:

Ever since Donald Trump was elected, and one could argue even in the months leading up to his election, journalistic standards have been consciously jettisoned when it comes to reporting on public figures who, in Smith’s words, are “most disliked by the loudest voices,” particularly when such reporting “swim[s] ably along with the tides of social media.” Put another way: As long the targets of one’s conspiracy theories and attacks are regarded as villains by the guardians of mainstream liberal social media circles, journalists reap endless career rewards for publishing unvetted and unproven — even false — attacks on such people, while never suffering any negative consequences when their stories are exposed as shabby frauds.

He’s talking about Russiagate.

(Readers, I’m being inundated with comments — a good thing! But I have very little time to interact with you all as I usually do. Thanks for your understanding. A note to new readers: you will not be published if your comment is an ad hominem attack on me or others who post here.)

UPDATE.2: Michael Luo, a New Yorker editor, rebuts in detail Ben Smith’s claims — and says that the magazine provided this to him in writing, but it didn’t make it into his story.

The post Ronan Farrow Discredited appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 19, 2020

Bo-Bolsheviks & Soft Totalitarianism

Here’s a fantastic piece by Nathan Pinkoski, on the particular qualities of contemporary American socialism. He writes that contemporary US socialists abandon the old socialist goal of replacing capitalism:

Self-styled American socialists leave this behind. They define socialism not by government control of the economy or by state ownership of the means of production, but rather in terms of an open-ended commitment to equality.

This means playing up issues of race and identity — which makes “socialism” much less hostile to the bourgeois class. Whence the bobos, or “bourgeois bohemians.” But the bobos are becoming more radicalized:

The new activity, making support for individual autonomy and self-creation the decisive issue, has the bobos denounce the bourgeois for their attitudes that are hostile to individual autonomy and self-creation, the practices that hold minorities back and get in the way of equality. Let us call these the practices of acknowledged dependency, whose paramount examples are found in familial and religious life.

The new socialists end up attacking the working class for its “problematic” views on race and identity. But notice, it’s not minority members of the working classes. Pinkoski says, “The new villain is not the bourgeois, but the white heterosexual American Christian male.”

Pinkoski says the socialist goal now is not to build up the working class. That’s over.

In its place are the new battlegrounds that Jean-Pierre Le Goff spotted: history, environmentalism, children’s literature, formal education of children, and human sexuality, where victory means extirpating the conscious and unconscious prejudices that belong to the villain’s culture. The goal is to negate the entirety of the existing culture.

To achieve that goal the bobos become “bo-Bolsheviks.”

Yes they do. Pinkoski says:

The disputes between socialists and progressives mask their fundamental, shared worldview: the bourgeois worldview of freedom as individual self-creation. American socialists may be anti-liberal on economics. But they are ultra-liberal about everything else.

Read it all. It is a superb analysis, though as Carlo Lancellotti has pointed out, Augusto Del Noce had all this figured out a generation ago.

See, this is a significant part of my claim, advanced in my forthcoming book Live Not By Lies, that we are moving into a condition of soft totalitarianism. The bo-Bolsheviks don’t really care about the state monopolizing the means of production on behalf of the working class. They care about authority (the state, corporations, universities, etc.) monopolizing the culture on behalf of those they regard as oppressed minorities. This is why, to use a Pinkoski example, nobody will bat an eye if you advocate for a flat tax, but if you dispute gender ideology, your career may be in jeopardy. The totalitarian core of these bo-Bolshevik attitudes doesn’t register with the middle-class people; they simply think that they are advancing the cause of justice.

The villain for these people may well be white heterosexual Christian males — and if you know and love any white heterosexual Christian males, you should care about this — but it won’t stop there. As the Columbia sociologist Musa al-Gharbi writes, blacks and Latinos are more socially conservative than the woke white people who assume the mantle of arguing for black and Latino interests.

What happens when the bo-Bolsheviks in power come for black and Latino church people? When the online discourse of socially conservative blacks, Latinos, and other minorities is monitored for wrongthink, and punished? Pinkoski is right: the goal of these bo-Bolsheviks is to “negate the entirety of the existing culture.” To do that will require totalitarian methods. It will not require gulags. It will only require gaining control of the cultural means of production (e.g., schools, media) and the administrative state. China’s social credit system offers a soft totalitarian model for them to follow — this, in part because the technological surveillance infrastructure is already largely in place. Some Americans are getting wound up about the possibility of government tracking them as an anti-Covid-19 strategy. People, wake up: most everything you do during the day, including everywhere you go, is already tracked via your smartphone. If you don’t believe me, when you get home, ask Alexa.

I’ll be glad when my book is out this fall, and we can talk about this in greater detail. If you’re interested in the topic, pre-order it for September 29 delivery.

The post Bo-Bolsheviks & Soft Totalitarianism appeared first on The American Conservative.

QAnon Church

On Feb. 23, I logged onto Zoom to observe the first public service of what is essentially a QAnon church operating out of the Omega Kingdom Ministry (OKM). I’ve spent 12 weeks attending this two-hour Sunday morning service.

What I’ve witnessed is an existing model of neo-charismatic home churches — the neo-charismatic movement is an offshoot of evangelical Protestant Christianity and is made up of thousands of independent organizations — where QAnon conspiracy theories are reinterpreted through the Bible. In turn, QAnon conspiracy theories serve as a lens to interpret the Bible itself.

More:

OKM is part of a network of independent congregations (or ekklesia) called Home Congregations Worldwide (HCW). The organization’s spiritual adviser is Mark Taylor, a self-proclaimed “Trump Prophet” and QAnon influencer with a large social media following on Twitter and YouTube.

The resource page of the HCW website only links to QAnon propaganda — including the documentary Fall Cabal by Dutch conspiracy theorist Janet Ossebaard, which is used to formally indoctrinate e-congregants into QAnon. This 10-part YouTube series was the core material for the weekly Bible study during QAnon church sessions I observed.

The Sunday service is led by Russ Wagner, leader of the Indiana-based OKM, and Kevin Bushey, a retired colonel running for election to the Maine House of Representatives.

And:

What is clear is that Wagner and Bushey are leveraging religious beliefs and their “authority” as a pastor and ex-military officer to indoctrinate attendees into the QAnon church. Their objective is to train congregants to form their own home congregations in the future and grow the movement.

Argentino points out that the number of participants in this church is relatively small (300 or so). Still, the point from his research is to document the birth of a new religion in real time.

This puts me in mind of what I now regard as one of the past decade’s most important essays about contemporary religion: a long 2016 piece by the Evangelical theologian Alastair Roberts about the Internet and the breakdown of authority in the church. Excerpts:

People’s hunger for truth is easily mistaken for a pure rational desire for accuracy and certitude. Yet our hunger for truth is, at a deeper level, our desperate need for something or, more typically, someone to trust. Where radical distrust in the ordinary organs of knowledge and thought in society prevails, most don’t cut themselves off from everyone else in unrelenting suspicion. Rather, in such situations we typically see a dangerous expansion of credulity, of unattached trust, just waiting for something to latch onto, for someone or something—anything!—to believe in. Alongside this expansion of credulity, we also see a shrinking of the circle of trust. Hence, wild and fanciful conspiracy theories gain traction, and new dissident and tribal communities form around them.

More:

The Internet has occasioned a dramatic diversification and expansion of our sources of information, while decreasing the power of traditional gatekeepers. We are surrounded by a bewildering excess of information of dubious quality, but the social processes by which we would formerly have dealt with such information, distilling meaning from it, have been weakened. Information is no longer largely pre-digested, pre-selected, and tested for us by the work of responsible gatekeepers, who help us to make sense of it. We are now deluged in senseless information and faced with armies of competing gatekeepers, producing a sense of disorientation and anxiety.

Where we are overwhelmed by senseless information, it is unsurprising that we will often retreat to the reassuring, yet highly partisan, echo chambers of social media, where we can find clear signals that pierce through the white noise of information that faces us online. Information is increasingly socially mediated in the current Internet: our social networks are the nets of trust with which we trawl the vast oceans of information online. As trust in traditional gatekeepers and authorities has weakened, we increasingly place our trust in less hierarchical social groups and filter our information through them.

And:

The power of traditional gatekeepers was largely established by public, civil, and religious institutions. These institutions typically had established standards to which their gatekeepers were held and processes by which they were selected. The trust in the gatekeepers arose in large measure from a trust in the institutional means by which they were selected, tested, and held accountable. These institutions—universities, political parties, churches, newspapers, publishing houses, etc., etc.—themselves provided the ‘gates’ to public discourse and participation. The keepers of the gates—selection committees, publishers, editors, pastors, theologians, etc., etc.—were produced by and defended their institutions. They were subject to training and a standard of excellence.

There are neither gates nor gatekeepers in the same way online. Instead of a well-ordered and bounded public square, a realm of discourse is thrown open for all and sundry. Much of the Internet functions as a radically egalitarian society, where no clear differentiation is made between people who are qualified to speak and those who are not. Everyone can now be a self-appointed opinionated expert, courtesy of Google and Wikipedia. It is also so much easier now to form movements and discourses that are independent of the institutions and agencies that could once maintain the standards of the public conversation and vet its participants.

In the rampant populism of the Internet, the notion that everyone has the right to their own opinion can go to seed. An egalitarianism and democracy of opinions neglects the reality that most people’s opinions on most subjects are unformed, untested, and quite worthless. The differences between mere opinionators and people with the authority and responsibility of office, extensive experience, or advanced research become blurred.

Roberts talks about the factors that have damaged trust in traditional institutional sources of authority. And then he gets to Evangelical churches. More:

Church leaders are increasingly facing a situation where members of their congregations have an ever-growing and diversifying interface with a dizzying array of different figures. Congregants are following people on Twitter and Facebook, reading various blogs, listening to podcasts, watching Christian videos on Youtube, participating in online forums and communities, reading a far wider range of books than they probably would have done in the past, watching Christian TV shows, listening to Christian radio stations, etc., etc., all within the comfort of their own houses. The sheer range of sources that the members of a congregation will be exposed to nowadays is entirely unprecedented. Although some may expect pastors to keep on top of all of this, I really don’t see how they realistically can.

The result has often been a situation—similar to that faced by vaccination programmes—in which pastors and church leaders urgently have to protect the spiritual health of their congregations against false teachings that untrained people have adopted through their independent ‘research’. In such a situation, few things are more important than a strong bond of trust between lay people and those in authority over them, who are responsible for their well-being.

However, that bond of trust has come under extreme and sustained assault in the last couple of decades. With the revelation of scandals of spiritual and sexual abuse and subsequent cover-ups and gross mishandling, pastors and church leaders are subject to much more suspicion. Pastors, prominent Christian leaders, and teachers may commonly presume that authority is something that comes with the job position. However, this election is just going to provide further evidence of how profoundly mistaken this assumption actually is. Especially among the up-and-coming generations, the older generation of prominent evangelical leaders has less and less influence. Their widespread support of Trump will just be the final nail in the coffin of their credibility for a large number of younger people. ‘Authority’ counts for little where trust no longer exists. Not only will this mean that their future statements won’t carry weight: they will be actively distrusted. Once again, there is a dangerous situation of unattached trust, ripe for the establishment of counter-communities.

Many people now privilege online bloggers, speakers, and writers over the pastors that have been given particular responsibility for the well-being of their souls. The result is growing competition among Christian gatekeepers, which increasingly positions the individual Christian, less as one fed by particular appointed and spiritually mature local fathers and mothers in the faith, and more as an independent religious consumer, free to pick and choose the voices that they find most agreeable. Sheep with a multitude of competing shepherds aren’t much better off than sheep with no shepherds whatsoever.

Roberts talks about how with the collapse of traditional authority within Evangelicalism, the vacuum has been filled by online “influencers” and others. “To understand the future of evangelicalism, there are few things more important than attending to currently shifting networks of trust,” Roberts says. He claims that Evangelicalism 25 years from now is going to look very different than it does today, in large part because the leaders of contemporary Evangelicalism have little trust among young Evangelical adults. Roberts puts the blame on leaders for squandering their authority, but I think that, in light of his analysis in this piece (read it all — it’s good, and it’s important), even the best, most morally sound Evangelical leaders would struggle in the face of the scattering power of the Internet and contemporary culture.

It’s interesting to think about Roberts’s points applied to the cultures of American Catholicism and American Orthodoxy. Though I am, of course, Orthodox, I know far less about the culture of American Orthodoxy than I do about Catholicism. This is because I have deliberately stayed out of online Orthodoxy; sometimes an Orthodox friend will write to say, “Oh man, did you see what they’re saying about you on [Orthodox online forum]?” I tell them no, I don’t read them, and I don’t read them on purpose. Plus, Orthodoxy in America is so small that it’s hard to get a good sampling of how American Orthodox think.

Orthodoxy is hierarchical and traditional, and I can only guess about the extent to which American Orthodox submit to the teaching authority of the bishops and the institutional Church, and the extent to which they believe that they are their own magisterium. I would be surprised, though, if my fellow US Orthodox had avoided the general dissipation of authority within our culture. But I really don’t know. Orthodox bishops are like I imagine Catholic bishops and the Pope were before John Paul II: as pillars that hold up the institution, but who aren’t heard from much. You can be confident that they’re not going to do anything crazy, theologically, so you don’t really have to pay attention to them. One of the most striking things about going from Catholicism to Orthodoxy is the massive difference between how religiously engaged intellectuals talk about the hierarchy. It almost never happens in Orthodoxy. One reason for that, I think, is that the tradition is regarded as so stable that the bishop is not going to mess with it, and doesn’t see innovating or otherwise messing with it as his role. This is good.

In Catholicism — the American version — it has long been noted that there are broadly three churches: progressives, conservatives, and (by far the biggest), the great non-ideological middle. In terms of shifting authority, it has been fascinating to observe how under Pope Francis, conservative Catholics who were staunch institutionalists under JP2 and BXVI are now more or less dissidents, whereas progressives who lauded freedom of conscience and so forth under the previous popes are now … staunch institutionalists! Of course conservatives would say that they are loyal to the authoritative teachings of the Catholic Church, and that that loyalty compels them to criticize Pope Francis when he departs from those teachings. I get that, and I think that if they are correct in their judgment of the Pope’s orthodoxy, then they are right to speak out. The loyalty of a Catholic is to the magisterial truth, not to the person of the Pope.

But consider how bizarre it is that any Catholic can question the orthodoxy of the Pope! Or, to put it another way, consider how bizarre it is that a pope could give faithful Catholics reason to doubt his orthodoxy, ever. This is the risk Francis has been running by frequently pushing the boundaries in his papacy. It has been disorienting for theologically conservative Catholics, who are accustomed to no daylight between the Pope and the Magisterium. On top of that there is the sex abuse scandal, in which the US Catholic episcopate savaged its own authority.

I don’t know how things roll with progressive Catholics, who have not been taking traditional authority within their church seriously for a long time. But for conservatives, I surmise that many of them rally around particular figures and websites. Through his popular YouTube ministry, Taylor Marshall, for example, probably exercises more de facto authority in the lives of Catholics who follow him than does their bishop.

Note well, readers: I don’t want to start an argument about whether this or that influencer is on the side of the angels or the demons. The point is that cultural and technological trends are widely dispersing authority within churches and church communities. The Covid-19 experience will advance this trend. The syncretistic QAnon church is a radical outlier, but it’s probably not as far from the experience of most of us as we would like to think.

The post QAnon Church appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 18, 2020

SSPX Abuse Scandal Hits Mainstream Media

About a month ago, I posted about a blockbuster Church Militant story on sexual abuse scandal within the traditionalist Society of St. Pius X, in particular in the town of St. Marys, Kansas, where the SSPX has a school and a big community. Church Militant kept writing about it (read all its coverage here), and SSPX answered some of their charges, but I lost track of the back and forth. Now I see that the Kansas City Star has a big report on the allegations and investigation. Excerpts:

For four decades, the Society of St. Pius X has made its home in this northeast Kansas town, its followers coming from across the country to raise their children according to traditional Catholic values.

Now, with attendance at Latin Mass topping 4,000, plans are underway for the breakaway Catholic society to build a $30 million church high on its campus overlooking St. Marys. The Immaculata, the SSPX says, will become the biggest traditional Catholic church in the world.

But something else is underway that threatens to overshadow the jubilation over a new house of worship with enough room to accommodate the ever-expanding flock: A criminal investigation by the state’s top law enforcement agency into allegations of priest sexual abuse.

Read it all. It’s a long story, and it mostly covers horrific ground already reported by Church Militant. Some of you readers didn’t want to believe Church Militant, on the grounds that its editors have an axe to grind with the SSPX. I don’t know anything about hostility between CM and SSPX, but if you were thinking that reporting by CM’s Christine Niles was just tabloid trash, as a couple of you said, you should be aware that the same allegations have now appeared in the state’s biggest newspaper.

This excerpt from the KC Star report is infuriating, but typical:

“There’s no benefit of the doubt anymore. This is corruption,” said Jassy Jacas, a St. Marys woman who recently posted details on her Facebook page of what she said was inappropriate behavior by an SSPX priest she had gone to for counseling.

Jacas said she reported her concerns all the way up the SSPX leadership chain starting in 2018 and was assured that action had been taken. But she said she later learned that no investigation was ever conducted and that the priest was serving as principal of an SSPX school in Florida.

… Some SSPX faithful strongly disagreed with Jacas’ actions.

“The SSPX has my support,” wrote one woman on the SSPX Facebook page. “Of course Satan is attacking the true Mass. We need to pray for our clergy.”

Another posted on Jacas’ Facebook page: “I know quite a few priests and never have I suspected them of inappropriate things. If by chance something did happen then why the hell don’t everyone stop posting things and start praying for our priests.”

There are some people who would rather sacrifice young people and vulnerable others than have their idols broken by facing ugly truths. We will have to see what the KBI’s investigation uncovers, but what looks like the refusal of the SSPX to face the truth at the time of the alleged abuse, and deal with it like Christians instead of like mafiosi, now puts the Society’s massive St. Marys project in jeopardy. One reason so many disillusioned traditional Catholics went to the SSPX is because they were seeking a haven from what they regarded as the manifold disorders of the Vatican II-era Catholic Church. They are now discovering that the grave disorders of humanity do not respect theological distinctions. One of the SSPX lay faithful that the Society in St. Marys is accused of protecting is now sitting in jail, having pled guilty to molesting his own children. That’s not something that you can look at and say, “Well, people sin, guess we better pray for our priest,” and just carry on as usual. There has to be a reckoning.

On September 29, 2018, after the McCarrick mess and Archbishop Vigano’s allegations of a cover-up, Father Jurgen Wegner, overseer of the SSPX in the United States, issued this letter to the faithful. It said, in part:

It is against this sorrowful backdrop that I wish to reiterate that the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX) takes any and all reports of illicit and illegal behavior on the part of its clergy, religious, employees and volunteers with utmost seriousness. Every report is submitted to a thoroughgoing investigation by the appropriate authorities within the Society and full cooperation is given to all law enforcement and official investigative agencies concerned, particularly when reports involve minor children. Moreover, any priest or religious of the SSPX found guilty of immorality is subject to sanctions under canon law, including removal from active ministry and laicization.

In an effort to forestall the spread of sin within its ranks, the SSPX abides by the Church’s longstanding and prudent prohibition on admitting men harboring same-sex or other unnatural sexual attractions to any of its seminaries, including St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary in Virginia. If, after admission to either seminary or holy orders, credible evidence is found of immoral inclinations or acts by an individual, said individual is immediately expelled from the seminary and/or the Society. And, if the evidence warrants, the matter is immediately referred to the ecclesiastical and secular authorities.

Not quite sure how they reconcile that stated policy with what happened in Kansas. Thank God that whistleblowers came out, and the secular authorities are investigation. What a shameful thing, though. How can people trust when the leadership says one thing, but does another — and in a matter as grave as the sexual abuse of children?

It has not escaped my notice that St. Marys is the kind of place that could be fairly identified as a Benedict Option community. To be sure, I have never, ever claimed, nor would I ever claim, that you can escape sin. Still, even though I’m no longer Catholic, I do find it particularly painful that this is going on within a community that really is trying to live by traditional standards. It doesn’t negate their aspirations to holiness, including communal holiness, but it does make it harder for people to trust the leadership.

The post SSPX Abuse Scandal Hits Mainstream Media appeared first on The American Conservative.

Hate Crimes & Hate Misdemeanors

Wall Street Journal columnist Gerard Baker says that the Ahmaud Arbery story is once again teaching us a lesson about what we can and cannot say about race and crime in America. It’s behind the paywall, the column, but here is an excerpt:

You probably haven’t heard of Paul and Lidia Marino. The couple, 86 and 85 years old, were shot dead a week ago while visiting a veterans’ cemetery in Bear, Del., where their son, who died in

2017, is buried. The authorities have so far been unable to establish a motive for the killing, but

they identified a suspect, Sheldon Francis, a 29-year-old black man, later found dead after an

exchange of fire with the police.

As far as I can tell, from news databases and online searches, other than local newspapers and

TV, and a brief story by the New York Post, the death of the Marinos, who were white, has gone

as unremarked as their lives. Mr. Arbery’s death, by contrast, has become one of those crimes

that some who control our public discourse have decided is a “teachable moment.”

Millions of words have been devoted to exploring and explaining the moral of the killing. It has

been widely described as a “lynching.” We have been reminded once again of the prevalence of

unequal and violent treatment of minorities. We’ve been told once again that the killing reflects

the daily reality of life in America for young blacks. This teaching moment has turned into a

continuous, ubiquitous lecture series on the unalterably racist nature of America.

We don’t yet know the full facts behind either of these killings. Mr. Arbery’s certainly looked

ugly, and whatever his killers and some neighbors allege he may have been doing on that street

on a sunny afternoon, he clearly did not deserve to be gunned down. We will learn no doubt

soon whether his killers did indeed have racist motives.

Perhaps, meanwhile, the murder of the Marinos was a random act of violence, a deranged killer,

a robbery that savagely escalated. But whatever the motive, I’d be willing to wager a small

fortune that we won’t hear much more about it.

Baker goes on to say that the most recent Justice Department figures (2018) show that there are more than twice as many hate crimes perpetrated against blacks as anti-white hate crimes. “But if you adjust the figures for the relative size of each group in the total U.S. population,” he writes, “they show that blacks are 50% overrepresented among perpetrators of hate crimes, while whites are about 25% underrepresented.”

The point Baker makes is that this is about constructing a narrative. Or to be more precise, the killing of Ahmaud Arbery — which Baker acknowledges was a horrible thing — both resonates with a pre-existing narrative dominant in the media, and provides another opportunity to reinforce that narrative. This is not “whataboutism” on Baker’s part. It is a perfectly reasonable questioning of the way we talk about hate crimes in our media. He says no fair person can deny that racism exists, but (he says) the systematic distortion of facts, the choice of the stories we tell (and those we don’t), and “the routine exclusion of countervailing evidence” against the preferred conclusion — all of these things make it harder to talk about racism.

Musa al-Gharbi, a Columbia sociologist, has a really interesting set of reflections about who gets to define “racism.” He writes that it’s great that racism has become so stigmatized in our society. Yet:

However, as a function of the increased social capital at stake when accusations of racism are made, and the diminishing opportunities to leverage that capital by “calling out” obvious cases of racism – the sphere of what counts as “racist” has been ever-expanding – to the point where it is now possible to qualify as “racist” on the basis of things like microaggressions and implicit attitudes.

One particularly unfortunate aspect of this concept creep – justified under the auspices of empowering people of color – is that relatively well-off, highly-educated, liberal whites tend to be among the most zealous in identifying and prosecuting these new forms of “racism.”

Data show that liberal, educated white people are much more likely to see racism in everyday actions than are black and Hispanic people. Al-Gharbi says that white elites are so eager to express their anti-racism that they don’t actually listen to black and Hispanic people. More:

White elites —who play an outsized role in defining racism in academia, the media, and the broader culture — instead seem to define ‘racism’ in ways that are congenial to their own preferences and priorities. Rather than actually dismantling white supremacy or meaningfully empowering people of color, efforts often seem to be oriented towards consolidating social and cultural capital in the hands of the ‘good’ whites. Charges of “racism,” for instance, are primarily deployed against the political opponents of upwardly-mobile, highly-educated progressive white people. Even to the point of branding prominent black or brown dissenters as race-traitors (despite the reality that, on average, blacks and Hispanics tend to be significantly more socially conservative and religious than whites).

And this, al-Gharbi says, drives some white people to vote for candidates like Donald Trump. Moreover, he says, research data show that there is no discernible negative effect from microaggressions, but there are measurable negative effects from making people of color hypersensitive to racism — that is, making them anxious that racism is getting ready to jump out and attack them at any second. And, research shows that the main effect of diversity training is to increase racial resentment.

Al-Gharbi says that those doing antiracism work need to change their ways. As it stands now, it only serves as a status marker. Performative antiracism, according to al-Gharbi, is often about high-status whites reinforcing their own power and privilege by putting low-status whites in their places.

This has a lot to do with the point Gerard Baker makes about reporting on hate crimes. Baker’s piece made me think about something I wrote back in 2002 about Mary Stachowicz. Ever heard of her? Of course you haven’t. She was a middle-aged Polish Catholic woman in Chicago who asked her neighbor, a 19-year-old gay man, why he preferred men to women. The man beat and tortured her to death, then shoved her body into a crawlspace. It was a hate crime. Barely anyone noticed. As I wrote then:

Yet the same American media that made Matthew Shepard a celebrated cause have said very little about Mary Stachowicz just as they said very little about Jesse Dirkhising, the 13-year-old boy raped, tortured and strangled by homosexuals in 1999.

Andrew Sullivan, probably the most articulate gay-rights advocate in journalism, wrote in a 2001 New Republic article:

“In the month after Shepard’s murder, Nexis recorded 3,007 stories about his death. In the month after Dirkhising’s murder, Nexis recorded 46 stories about his. In all of last year, only one article about Dirkhising appeared in a major mainstream newspaper. The Boston Globe, the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times ignored the incident completely. In the same period, the New York Times published 45 stories about Shepard, and The Washington Post published 28. The discrepancy isn’t just real. It’s staggering.”

Dirkhising’s and Stachowicz’s deaths violated the narrative. So too, one surmises, will the deaths of Paul and Lidia Marino if it emerges that the black man who executed them (and then killed himself) was motivated by racial hatred.

Though we could learn more through the investigation, everything we know about the killing of Ahmaud Arbery indicates that it was a racially motivated homicide, and that the local DA ran interference to protect the men who shot Arbery. If what seems to be true turns out to be accurate, then this is real outrage. Attention must be paid (seriously), and wrongdoers punished. Protesters are right to demand justice.

But the media’s longstanding habit of finding some victims of violent hate crimes more worthy of attention than others makes people skeptical and even resentful of the narrative. And again, it’s not whataboutism to point out this chronic flaw in the way the media construe stories having to do with racism and violence in America.

UPDATE: I knew this would be a thing in the comments section, and sure enough it was. Let me say a second time: I think what happened to Arbery, and the local DA’s attempt to make it go away, was an outrage, and that the protests are just. Some of y’all need to understand that several things can be true at the same time.

The post Hate Crimes & Hate Misdemeanors appeared first on The American Conservative.

Queerness: America’s Post-Christian Gnosticism

Here’s a superb First Things piece by Darel Paul in which he explains why queerness conquered American culture. It’s a terrific piece of cultural analysis. Excerpts:

Queerness has conquered America because it is the distilled essence of the country’s post-1960s therapeutic culture. The therapeutic originates with Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. From its beginning, the goal of psychoanalysis has been the salvation of the suffering self. Therapeutic practices of introspection seek to reveal the unacknowledged sources of psychic suffering. Sexual desire plays an especially prominent role in therapeutic narratives. For Freud, sexual drive was the engine of the personality. He believed both men and women are bisexual in nature and direct their sexual drives toward diverse objects. In this way, the therapeutic not only obscures gender differences and grants wide berth to atypical sexual expressions, it also blurs the distinction between normality and pathology, making every self a neurotic one on an eternal quest for “mental health.”

More:

Queerness owes its privileged status to its relationship to the therapeutic. It epitomizes three central therapeutic values: individuality, authenticity, and liberation. Individual rights, of course, have long been the beating heart of the American creed. Yet the therapeutic turns traditional American individualism into individuality, wedding the former to a romantic sensibility of the self as a unique and creative spirit whose reason for existence is its own expression. None have summarized such individuality better than America’s philosopher-king, former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, who in 1992 famously defended “the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Although Kennedy wrote these words in defense of the right to abortion, he quoted them when ending the last of America’s sodomy laws in 2003 and echoed them as he constitutionalized same-sex marriage in 2015 as an expression of the right “to define and express [one’s] identity.”

And:

Like individuality, authenticity has exceptionally strong cultural connections to queerness. Sexual orientation, sexual identity, and gender identity are invisible qualities of the self traditionally subject to strong social control. Therefore, the experience of psychic trauma associated with suppressing the authentic self “in the closet” is particularly attached to queer persons. So, too, is “coming out,” a pure act of public self-revelation in the name of authenticity. This combination makes queerness a powerful symbol of therapeutic values.

In the piece, Prof. Paul discusses how the word “Love” has come to mean “the social recognition of authentic selves,” at least when discussed in relation to the LGBT rights movement. In this sense, “love” has been drained of all its self-giving, sacrificial meaning, and has been reduced to the dimension of giving the queer person what he or she wants. “Love” is this Gillette razor ad in which a father shows “love” for his female-to-male transgender son, by helping her to learn how to shave. When I was in Poland researching my next book, an historian of the communist era told me that the regime back then hollowed out the usual meaning of words, as a way of controlling thoughts. To be a “patriot,” for example, was to be willing to inform the secret police about your friends and family. The historian told me that the postcommunist generation has no awareness of how this kind of thing works, and therefore has no natural immunity to it. Anyway, if homosexuality and transgenderism had nothing to do with it at all, using “love” to refer to “the social recognition of authentic selves” would still signal a massive social shift.

Along those lines, it is interesting to think of how the word “Pride” has been transformed by the LGBT movement from a traditional vice into a virtue in our culture — but of course only when it refers to sexual aberration. I know where it comes from: in the old days, the dominant culture made gays feel shame for their desires; they flipped “shame” around. I get that. Still, there is a reason why Pride is a deadly sin. It is at the root of the primordial sin: asserting that one is one’s own God, not God. The Ur-sin of Lucifer is Pride. Reading Prof. Paul’s analysis this morning brought to mind this passage from Live Not By Lies, about pre-revolutionary Russian culture:

Regarding transgressive sexuality as a social good was not an innovation of the Sexual Revolution. Like the contemporary West, late imperial Russia was also awash in what historian James Billington called “a preoccupation with sex that is quite without parallel in earlier Russian culture.” Among the social and intellectual elite, sexual adventurism, celebrations of perversion, and all manner of sensuality was common. And not just among the elites: the laboring masses, alone in the city, with no church to bind their consciences with guilt, or village gossips to shame them, found comfort in sex.

The end of official censorship after the 1905 uprising opened the floodgates to erotic literature, which found renewal in sexual passion. “The sensualism of the age was in a very intimate sense demonic,” Billington writes, detailing how the figure of Satan became a Romantic hero for artists and musicians. They admired the diabolic willingness to stop at nothing to satisfy one’s desires, and to exercise one’s will.

So that worked out well for the Russians, didn’t it?

I’m sorry that you all have to wait till November to read what is one of the very best analyses of the therapeutic culture from a small-o orthodox Christian perspective that I’ve ever read: Carl R. Trueman’s The Rise And Triumph Of The Modern Self. The publisher asked me to consider writing the foreword. When I read the manuscript, I was genuinely excited, because this is exactly the kind of deep analysis, put in the language of everyday people, that Christians have desperately needed. Of course I said yes to writing the foreword.

What you learn from the Trueman book is the ways in which we have radically destabilized our culture through the pursuit of a certain idea of authenticity and selfhood. Queerness is not an aberration of this Grand March to self-liberation, but rather its fulfillment. It is the triumph of gnosticism: the idea that matter is a prison that willful spirit is meant to overcome. At this late stage of our civilization’s self-destruction, I feel that the most important task of us Christians is to keep this gnosticism out of the church. Given how the therapeutic ethos has conquered popular American Christianity, this is going to be a fierce battle.

Transgenderism is fullest expression of contemporary pop gnosticism. It is no coincidence that the Wachowskis, the sibling team behind The Matrix, the most gnostic film ever, both ended up as transgendered females. (See this short 2015 Sonny Bunch essay on the siblings’ obsession with the mutability of man, and their recurrent villainization of metaphysical order. This more recent Vox essay, written by a male-to-female transgender, goes much deeper into the trans philosophy at the heart of the Wachowskis’ work; the author says that The Matrix is “a story that is now widely read as an allegory about how immensely powerful it can be to discover one’s true self by getting online.”)

We, as a culture, have come to believe that boundaries exist to be transgressed, and that the hero is the one who transgresses boundaries in pursuit of the authentic self. This is the central myth of our contemporary culture. It is told, and re-told, in movies, music, news media, advertising, and academia. What’s interesting is that not all boundaries are there to be transgressed — only those having to do with sex and identity. But I have digressed too much already in this post.

The point is this: to queer a social order and a culture, as has happened, requires replacing one set of metaphysical assumptions with another — and that inevitably manifests as a changed morality. Queerness didn’t cause this; it is more the fulfillment of a metaphysic that has long been implicit in the post-Christian West, and that took a therapeutic form in the early 20th century. (Nietzsche saw more clearly than the therapeutics, but that’s another story.) Hannah Arendt, in The Origins Of Totalitarianism, said that transgressiveness was in vogue in pre-totalitarian Germany and Russia, and that elites were happy to destroy the boundaries upon which their social orders had been built:

The members of the elite did not object at all to paying a price, the destruction of civilization, for the fun of seeing how those who had been excluded unjustly in the past forced their way into it.

What is past is prologue. You just watch.

The post Queerness: America’s Post-Christian Gnosticism appeared first on The American Conservative.

May 17, 2020

QAnon & Living By Lies

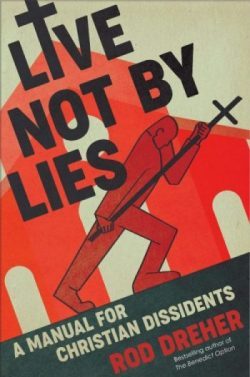

I’m very pleased to be able to share with you all the cover for my next book, which will be published on September 29. You can pre-order it in hardcover here, and in Kindle format here. My editor Bria Sandford and I are very pleased with the design provided by the art department at Sentinel. We had suggested the Soviet-era constructivist aesthetic, which seemed subversive, given that the stories in the book are from people who resisted the Soviets. The cover conveys the urgency and dynamism of the book’s content, I think. I wish I knew the name of the designer so I could praise him or her publicly:

As you regular readers know, this book is about the creeping “soft totalitarianism” in our society, and what Christian dissidents who lived under Soviet bloc communism can tell us about how to recognize it and resist it. In its most simple definition, “totalitarianism” is a word used to describe a state in which all things are politicized. The key difference between authoritarianism and totalitarianism is in the first, the state only seeks a monopoly on political action, whereas in the latter, the state wants to command all aspects of life, and — this is key — to compel not only obedience, but internal assent. As Winston Smith was told, you must learn to love Big Brother.

The word was invented in fascist Italy, but has been applied both to Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and its vassals. One consistent story that we have heard from anti-communist dissidents is that the entire system was built on lies — that is, on the willingness of people to assent to lies. Vaclav Havel (who was not a Christian) said that the only resistance available to people under communism, where it was impossible to build political opposition, was to seek to “live in truth” — that is, to refuse to participate in lies. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was even more emphatic on this point. The title of my book is taken from his final message to the Soviet people in 1974, on the eve of his expulsion from the country. That essay, “Live Not By Lies,”

urged readers to engage in passive resistance to the regime of lies: that is, to refuse to say, or to appear to say, something that they believe is untrue, just to keep the peace. Solzhenitsyn wrote:

So in our timidity, let each of us make a choice: Whether consciously, to remain a servant of falsehood—of course, it is not out of inclination, but to feed one’s family, that one raises his children in the spirit of lies—or to shrug off the lies and become an honest man worthy of respect both by one’s children and contemporaries. …

No, it will not be the same for everybody at first. Some, at first, will lose their jobs. For young people who want to live with truth, this will, in the beginning, complicate their young lives very much, because the required recitations are stuffed with lies, and it is necessary to make a choice.

But there are no loopholes for anybody who wants to be honest. On any given day any one of us will be confronted with at least one of the above-mentioned choices even in the most secure of the technical sciences. Either truth or falsehood: Toward spiritual independence or toward spiritual servitude.

And he who is not sufficiently courageous even to defend his soul—don’t let him be proud of his “progressive” views, don’t let him boast that he is an academician or a people’s artist, a merited figure, or a general—let him say to himself: I am in the herd, and a coward. It’s all the same to me as long as I’m fed and warm.

That is the spirit in which this book was written, and its content. I will be saying a lot more about it as we get closer to the publication date, September 29.

The stories I tell in the second half of the book are really moving — testimonies from people who survived communism, explaining with they did and how they did it — but they would strike readers as merely inspirational stories without the first half of the book to give context. The first part of the book is a cultural and historical analysis that attempts to explain why we are today in a pre-totalitarian environment, and the ways in which progressives are taking advantage of that to push a soft version of total control. I will explain that in much greater detail as we get closer to the publication date.

Totalitarianism isn’t just a left-wing or a right-wing thing, though. Hannah Arendt, in her 1950s study The Origins of Totalitarianism, examined the similarities between both the Nazi and the Communist version of it. I do not believe that we are in serious danger in the United States of a right-wing version of soft totalitarianism, for various reasons. The danger from the right is authoritarianism — which is a bad thing, but a different thing. As you’ll see in the book, the main reasons I believe the real threat comes from the left has to do with the fact that the values of the progressive left are dominant in Americans under 40 (meaning that the future is on the left); the fact that the institutional elites are heavily dominated by cultural progressives; that progressivism is illiberal, and will not tolerate dissent; and that our society has become one in which the masses want nothing more than comfort and happiness. We are preparing for a soft Huxleyan totalitarianism, not a hard Orwellian one.